NO ORIGIN

WE ALL REMEMBER ONE OF OUR FIRST VIEWS OF THE MICROSCOPIC WORLD, the intricate latticework of an enlarged snowflake crystal, in all its startling elegance. My own initial glimpse came during the projection of a well-worn 16mm film on a cinder-block wall in a small elementary-school science classroom. From that point forward, I could never hear certain words…design, order, mathematics, or, later on, Bach, without also seeing that snowflake in my mind. Funnily enough, the only thing that didn’t conjure up that delicate crystal were the words snow, snowfall, or snowflake. In some way, the enlarged pattern had become something apart unto itself, a separate thing with no origin, no pre-assigned purpose or definition. It was just a pure visual experience, devoid of context, complete and distinct.

I still experience that thrill when using a camera to remove the context from everyday objects, forcing them to be considered free of “backstory” or familiarity. I love it when people react to a photograph of light patterns that just “are”, without bringing to it the need to have the thing explained or placed in any particular setting. The easiest way to do this is through magnification, since many things we consider commonplace are, when isolated and amplified, ripe with details and patterns, that, at normal size, are essentially invisible to us. Another way to do it is to take away the things that the subject is normally seen as part of, or adjacent to. Again, magnification does much of this for us, allowing us to frame a single gear inside a machine or zone in on one connection in larger universes of function.

However this viewpoint is obtained, it can be very freeing because you are suddenly working with little more than the effect of light itself. You arrive at a place where a photographic image needn’t be about anything, where you’re working in simple absolutes of shape and composition. At the same time, you’re also conferring that freedom on your viewers, since they are also released from the prison of literalism. They can admire, even love, a pure composition for no relatable reason, just as we all did with our old stencil kits and Spirographs.

This all takes us full circle to our earliest days, and one of the first experiences any of us had as designers. Remember being told to fold a piece of construction paper in half, then half again, then half again? Recall being invited to randomly cut away chunks from the perimeter of that square, any way we wanted? Remember the wonder of unfolding it to see our cuts mirrored, doubled, cubed into a stunning design?

Remember what the teacher said when we unveiled our masterpieces?

Oh, look, class, she said, you’ve made a snowflake.

AS DIFFERENT AS DAY AND NIGHT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY OFTEN PRESENTS ITSELF AS A SUDDEN, REACTIVE OPPORTUNITY, a moment in time where certain light and compositional conditions seem ripe for either recording or interpreting. In such cases there may be little chance to ponder the best way to visualize the subject at hand, and so we snap up the visualization that’s presented in the moment. It’s the kind of use-it-or-lose-it bargain we’re all acquainted with. Sometimes it yields something amazing. Other times we do the best with what we’re handed, and it looks like it.

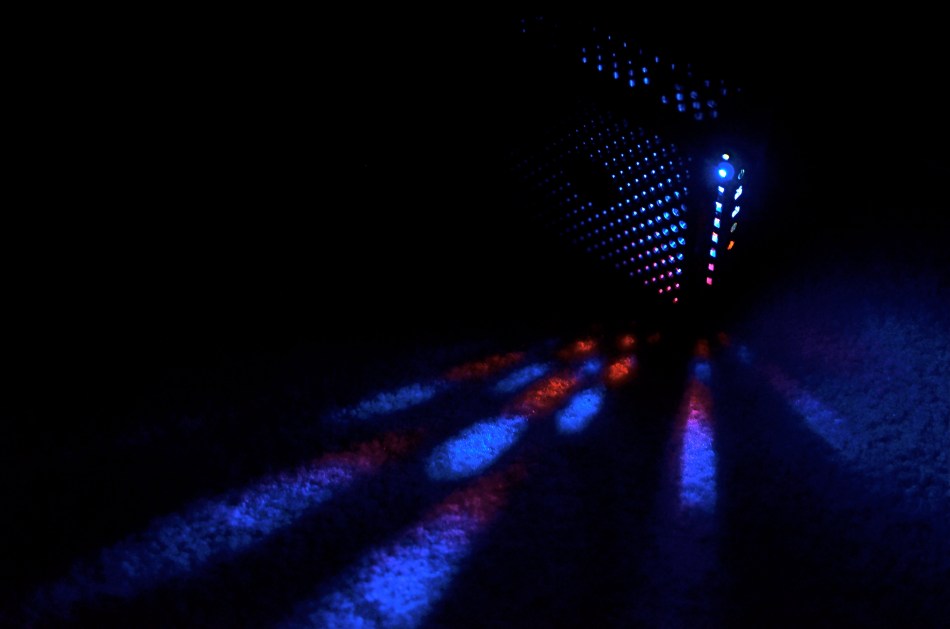

Having the option to shape light as we like takes time and deliberate planning, as anyone who has done any kind of studio set-up will attest. The stronger your conception to start with, the better chance you have of devising a light strategy for making that idea real. That’s why I regard light painting, which I’ve written about here several times, as a great exercise in building your image’s visual identity in stages. You slow down and make the photograph evolve, working upwards from absolute darkness.

Shock-Top, 2014. Light-painted with a hand-held LED over the course of a six-second exposure, at f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

To refresh, light painting refers to the selective handheld illumination of subjects for a particular look or effect. The path that your flashlight or LED takes across your subject’s contours during a tripod-mounted time exposure can vary dramatically, based on your moving your light source either right or left, arcing up or down, flickering it, or using it as a constant source. Light painting is different from the conditions of, say, a product shoot, where the idea is to supply enough light to make the image appear “normal” in a daytime orientation. Painting with light is a bit like wielding a magic wand, in that you can produce an endless number of looks as you develop your own concept of what the final image should project in terms of mood. It isn’t shooting in a “realistic” manner, which is why the best light painters can render subjects super-real, un-real, abstract or combinations of all three. Fact is, the most amazing paint-lit photos often completely violate the normal paths of natural light. And that’s fine.

In light painting, I believe that total darkness in the space surrounding your central subject is as important a compositional tool as how your subject itself is arranged. As a strong contrast, it calls immediate and total attention to what you choose to illuminate. I also think that the grain, texture and dimensional quality of the subject can be drastically changed by altering which parts of it are lit, as in the shock of wheat seen here. In daylight, half of the plant’s detail can be lost in a kind of brown neutrality, but, when light painted, its filaments, blossoms and staffs all relate boldly to each other in fresh ways; the language of light and shadow has been re-ordered. Pictorially, it becomes a more complex object. It’s actually freed from the restraints of looking “real” or “normal”.

Developed beyond its initial novelty, light painting isn’t an effect or a gimmick. It’s another technique for shaping light, which is really our aim anytime we take off our lens caps.

ELEMENTARY, MY DEAR NIKON

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY IS OFTEN DEFINED CLASSICALLY AS “WRITING WITH LIGHT“, but I often wonder if a better definition might be “capitalizing on light opportunities”, since it’s not really what subject matter we shoot but light’s role in shaping it that makes for strong images. We have all seen humble objects transformed, even rendered iconic, based on how a shooter perceives the value of light, then shapes it to his ends. That’s why even simple patterns that consist of little more than light itself can sometimes be enough for a solid photograph.

If you track the history of our art from, say, from the American Civil War through today’s digital domain, you really see a progression from recording to interpreting. If the first generally distributed photographs seen by a mass audience involve, say, the aftermath of Antietam or Gettysburg, and recent images are often composed of simple shapes, then the progression is very easy to track. The essence is this: we began with photography as technology, the answer to a scientific conundrum. How do we stop and fix time in a physical storage device? Once that very basic aim was achieved, photographers went from trying to just get some image (hey, it worked!) to having a greater say in what kind of image they wanted. It was at this point that photography took on the same creative freedom as painting. Brushes, cameras, it doesn’t matter. They are just mediums through which the imagination is channeled.

In interpreting patterns of elementary shapes which appeal on their own merit, photographers are released from the stricture of having to endlessly search for “something to shoot”. Some days there is no magnificent sunrise or eloquent tree readily at hand, but there is always light and its power to refract, scatter, and recombine for effect. It’s often said that photography forced painting into abstraction because it didn’t want to compete with the technically perfect way that the camera could record the world. However, photography also evolved beyond the point where just rendering reality was enough. We moved from being reporters to commentators, if you like. Making that journey in your own work (and at your own pace) is one of the most important step an art, or an artist, can take.

SETTING THE CAPTIVES FREE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’D LIKE TO ERADICATE THE WORD “CAPTURE” FROM MOST PHOTOGRAPHIC CONVERSATIONS. It suggests something stiff or inflexible to me, as if there is only one optimum way to apprehend a moment in an image. Especially in the case of portraits, I don’t think that there can be a single way to render a face, one perfect result that says everything about a person in a scant second of recording. If I didn’t capture something, does that mean my subject “got away” in some way, eluded me, remains hidden? Far from it. I can take thirty exposures of the same face and show you thirty different people. The word has become overused to the point of meaningless.

We are all conditioned to think along certain bias lines to consider a photograph well done or poorly done, and those lines are fairly narrow. We defer to sharpness over softness. We prefer brightly lit to mysteriously dark. We favor naturalistically colored and framed recordings of subjects to interpretations that keep color and composition “codes” fluid, or even reject them outright. It takes a lot of shooting to break out of these strictures, but we need to make this escape if we are to move toward anything approaching a style of our own.

I remember being startled in 1966 when I first saw Jerry Schatzberg’s photograph of Bob Dylan on the cover of the Blonde On Blonde album. How did the editor let this shot through? It’s blurred. It’s a mistake. It doesn’t…..wait, I can’t get that face out of my head. It’s Bob Dylan right now, so right now that he couldn’t be bothered to stand still long enough for a snap. The photo really does (last time I say this) capture something fleeting about the electrical, instantaneous flow of events that Dylan is swept up in. It moves. It breathes. And it’s more significant in view of the fact that there were plenty of pin-sharp frames to choose from in that very same shoot. That means Schatzberg and Dylan picked the softer one on purpose.

There are times when one 10th of a second too slow, one stop too small, is just right for making the magic happen. This is where I would usually mention breaking a few eggs to make an omelette, but for those of you on low-cholesterol diets, let’s just say that n0 rule works all the time, and that there’s more than one way to skin (or capture) a cat.

THE UNSEEN GEOMETRY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE MANY PHOTO SITES THAT SUGGEST SHOOTS CALLED “WALKABOUTS“, informal outings intended to force photographers to shoot whatever comes to hand with as fresh an eye as possible. Some walkabouts are severe, in that they are confined to the hyper-familiar surroundings of your own local neighborhood; others are about dropping yourself into a completely random location and making images out of either the nothing of the area or the something of what you can train yourself to see.

Walks can startle you or bore you to tears (both on some days), but they will sharpen your approach to picture-making, since what you do is far more important than what you’re pointing to. And the discipline is sound: you can’t hardly miss taking shots of cute cats or July 4 fireworks, but neither will you learn very much that is new. Forcing yourself to abandon flashier or more obvious subjects teaches you to imbue anything with meaning or impact, a skill which is, over a lifetime, beyond price.

One of the things I try to keep in mind is how much of our everyday environment is designed to be “invisible”, or at least harder to see. Urban infrastructure is all around us, but its fixtures and connections tend to be what I call the unseen geometry, networks of service and connectivity to which we simply pay no attention, thus rendering them unseeable even to our photographer’s eye. And yet infrastructure has its own visual grammar, giving up patterns, even poetry when placed into a context of pure design.

The above power tower, located in a neighborhood which, trust me, is not brimming with beauty, gave me the look of an aerial superhighway, given the sheer intricacy of its connective grid. The daylight on the day I was shooting softened and prettied the rig to too great a degree, so I shot it in monochrome and applied a polarizing filter to make the tower pop a little bit from the sky behind it. A little contrast adjustment and a few experimental framing to increase the drama of the capture angle, and I was just about where I wanted to be.

I had to look up beyond eye (and street) level to recognize that something strong, even eloquent was just inches away from me. But that’s what a walkabout is for. Unseen geometry, untold stories.

IN STEICHEN’S SHADOW

“Le Regiment Plastique”. Shot in a dark room and light-painted from the top edge of the composition. 5 seconds, f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’VE POSTED SEVERAL PIECES HERE ON “LIGHT-PAINTING”, or the practice of manually applying light to selective areas of objects during long exposures in the dark. The ability to “paint” additional colors, highlights and shadows “onto” even the most mundane materials can transform the whole light-to-dark ratio of the familiar and render it in new, if unpredictable ways. It’s kind of random and a lot of hands-on fun.

Some of the greatest transformations of ordinary objects ever seen in photography were obtained by Edward Steichen, arguably the greatest shooter in any style over the entire 20th century. Working for advertising agency J.Walter Thompson in the 1930’s, Steichen managed to romanticize everything from perfume bottles to kitchen matches to cutlery by arranging visually original ballets not only of these everyday items, but, through multiple source lighting, creating geometrically intricate patterns of shadows. His success in morphing the most common elements of our lives into fascinating abstractions remains the final word on this kind of lighting, and it’s fun to use light painting to pay tribute to it.

For my own tabletop arrangement of spoons, knives and forks, seen here, I am using clear plastic cutlery instead of silver (fashions change, alas), but that actually allows any light I paint into the scene to make the utensils fairly glow with clear definition. You can’t really paint onto or across the items, since they will pick up too much hot glare after even a few seconds, but you can light from the edge of the table underneath them, giving them plenty of shadow-casting power without whiting out. I took over 25 frames of this arrangement from various angles, since light painting is all about the randomness of effect achieved with just a few inches’ deviation in approach, and, as with all photography, the more editing choices at the end, the better.

The whole thing is really just an exercise in forced re-imagining, in making yourself consider the objects as visually new. Think of it as a puff of fresh air blowing the cobwebs out of your perception of what you “know”. Emulating even a small part of Steichen’s vast output is like me flapping my wings and trying to become a bald eagle, so let’s call it a tribute.

Or envy embodied in action.

Or both.

THE FULLNESS OF EMPTY

By MICHAEL PERKINS SCIENCE TELLS US THAT SOME HUSBANDS HEAR THE QUESTION, “DID YOU TAKE THE TRASH OUT?” more often than any other phrase over the course of their married life. If you are an intrepid road warrior, you may hear more of something like “do you know where you’re going?” or “why don’t you just stop and ask for directions?”. If you’re a less than optimum companion, the most frequently heard statement might be along the lines of “and just where have you been?”. For me, at least when I have a camera in my hands, it’s always been “why don’t you ever take pictures of people?”

Why, indeed.

Of course, I contend that, if you were to take a random sample of any 100 of my photographs, there would be a fair representation of the human animal within that swatch of work. Not 85% percent, certainly, but you wouldn’t think you were watching snapshots from I Am Legend. However, I can’t deny that I have always seen stories in empty spaces or building faces, stories that may or may not resonate with everyone. It’s a definite bias, but it’s one of the closest things to a style or a vision that I have.

I think that absent people, as measured in their after-echoes in the places where they have been, speak quite clearly, and I am not alone in this view. Putting a person that I don’t even know into an image, just to demonstrate scope or scale, can be, to me, more dehumanizing than taking a picture without a person in it. My people-less photos don’t strike me as lonely, and I don’t feel that there is anything “missing” in such compositions. I can see these folks even when they are not there, and, if I do my job, so can those who view the results later.

Are such photographs “sad”, or merely a commentary on the transitory nature of things? Can’t you photograph a house where someone no longer lives and conjure an essence of the energy that once dwelt within those walls? Can’t a grave marker evoke a person as well as a wallet photo of them in happier times? I ask myself these questions, along with other crucial queries like, “what time is the game on?” or, “what do you have to do to get a beer in this place?” Some answers come quicker than others.

I can’t account for what amounts to “sad” or “lonely” when someone else looks at a picture. I try to take responsibility for the pictures I make, but people, while a key part of each photographic decision, sometimes do not need to serve as the decisive visual component in them. The moment will dictate. So, my answer to one of life’s most persistent questions is a polite, “why, dear, I do take pictures of people.”

Just not always.

TRY A DIFFERENT DOOR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PUBLIC PLACES, ESPECIALLY RECREATION SPACES, ARE A REAL STUDY IN IMAGE CONTROL. The world’s playgrounds and theme parks are, of course, in the business of razzle-dazzle, and their marquees, grand courts and official entrances are carefully crafted facades designed to delight. For photographers, that usually means we all take the same pictures of the same Magic Gate or Super Coaster or whatever. Great for convenience: not so great for photography.

I’m not saying that it’s impossible to improvise a different way to frame something new in shooting something overly familiar. But I am saying that sneaking around to the service entrance can have its points, too, offering a flavor of things that are a little funkier, a little less polished, a little less ready for prime time. I recall my dad, who, years ago, dreamed of taking the ultimate “real” shots of the circus, trolling around near some of the lesser-traveled entrances and halls, trying to catch the clowns and acrobats either just before or just after their time in the ring. I still pursue that strategy sometimes.

Pacific Park, the amusement center along the boardwalk at the Santa Monica pier, is a predictably colorful, semi-cheesy mix of carny sights and smells. The main foot traffic is straight down the pier to the fishing lookout, but there are alternate ways to get there along the back of the ride and games section. This shot is rather gauzy, as it’s taken through some sun-flecked netting, softening the color (and the appearance of reality) for some gaming areas. I took a lot of standard stuff on this day, but I keep coming back to this frame. It’s not a work of art, by any means, but I like the feeling that I’m not supposed to be there.

Of course, where I’m not supposed to be is, photographically, exactly where I want to be.

You never know when you might spy a clown without his rubber nose.

MINUTE TO MINUTE

Going, Going: Dusk giveth you gifts, but it taketh them away pretty fast, too. 1/40 sec., f/3.5, ISO 200, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

VOLUMES HAVE BEEN WRITTEN ABOUT THE WONDROUS PHENOMENON OF “GOLDEN HOUR“, that miraculous daily window of time between late afternoon and early evening when shadows grow long and colors grow deep and rich. And nearly all authors on the subject, whatever their other comments, reiterate the same advice: stay loose and stay ready.

Golden hour light changes so quickly that anything that you are shooting will be vastly different within a few moments, with its own quirky demands for exposure and contrast. Basic rule: if you’re thinking about making a picture of an effect of atmosphere, do it now. This is especially true if you are on foot, all alone in an area, packing only one camera with one lens. Waiting means losing.

The refraction of light through clouds, the angle of the sun as it speeds toward the horizon, the arrangement between glowing bright and super-dark….all these variables are shifting constantly, and you will lose if you snooze. It’s not a time for meditative patience. It’s a time for reactivity.

I start dusk “walkarounds” when all light still looks relatively normal, if a bit richer. It gives me just a little extra time to get a quick look at shots that may, suddenly, evolve into something. Sometimes, as in the frame above, I will like a very contrasty scene, and have to shoot it whether it’s perfect or not. It will not get better, and will almost certainly get worse. As it is, in this shot, I have already lost some detail in the front of the building on the right, and the lighted garden restaurant on the left is a little warmer than I’d like, but the shot will be completely beyond reach in just a few minutes, so in this case, I’m for squeezing off a few variations on what’s in front of me. I’ve been pleasantly surprised more than once after getting back home.

What’s fun about this particular subject is that one half of the frame looks cold, dead, “closed” if you will, while there is life and energy on the left. No real story beyond that, but that can sometimes be enough. Golden hour will often give you transitory goodies, with its more dramatic colors lending a little more heft to things. I can’t see anything about this scene that would be as intriguing in broad daylight, but here, the hues give you a little magic.

Golden hour is a little like shooting basketballs at Chuck E. Cheese. You have less time than you’d like to be accurate, and you may or may not get enough tickets for a round of Skee-Ball.

But hey.

WORK AT A DISADVANTAGE

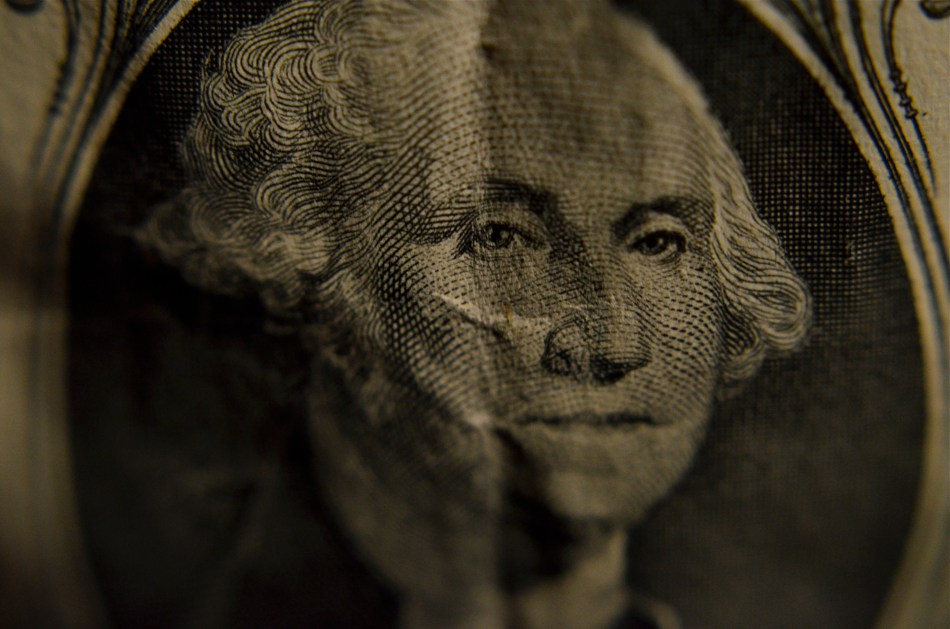

Focus. Scale. Context. Everything’s on the table when you’re trolling for ideas. 1/100 sec., f/5.6, ISO 800, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“IS THERE NO ONE ON THIS PLANET TO EVEN CHALLENGE ME??“, shouts a frustrated General Zod in Superman II as he realizes that not one person on Earth (okay, maybe one guy) can give him a fair run for his money. Zod is facing a crisis in personal growth. He is master of his domain (http://www.Ismashedtheworld.com), and it’s a dead bore. No new worlds to conquer. No flexing beyond his comfort zone. Except, you know, for that Kryptonian upstart.

Zod would have related to the average photographer, who also asks if there is “anyone on the planet to challenge him”. Hey, we all walk through the Valley Of The Shadow Of ‘My Mojo’s Gone’. Thing is, you can’t cure a dead patch by waiting for a guy in blue tights to come along and tweak your nose. You have to provide your own tweak, forcing yourself back into the golden mindset you enjoyed back when you were a dumb amateur. You remember, that golden age when your uncertainly actually keened up your awareness, and made you embrace risk. When you did what you could since you didn’t know what you could do.

You gotta put yourself at a disadvantage. Tie one hand behind your back. Wear a blindfold. Or, better yet, make up a “no ideas” list of things that will kick you out of the hammock and make you feel, again, like a beginner. Some ways to go:

1.Shoot with a camera or lens you hate and would rather avoid. 2.Do a complete shoot forcing yourself to make all the images with a single lens, convenient or not. 3.Use someone else’s camera. 4.Choose a subject that you’ve already covered extensively and dare yourself to show something different in it. 5.Produce a beautiful or compelling image of a subject you loathe. 6.Change the visual context of an overly familiar object (famous building, landmark, etc.) and force your viewer to see it completely differently. 7.Shoot everything in manual. 8.Make something great from a sloppy exposure or an imprecise focus. 9.Go for an entire week straight out of the camera. 10.Shoot naked.

Okay, that last one was to make sure you’re still awake. Of course, if nudity gets your creative motor running, then by all means, check local ordinances and let your freak flag fly. The point is, Zod didn’t have to wait for Superman. A little self-directed tough love would have got him out of his rut. Comfort is the dread foe of creativity. I’m not saying you have to go all Van Gogh and hack off your ear. But you’d better bleed just a little, or else get used to imitating instead of innovating, repeating instead of re-imagining.

DO SOMETHING MEANINGLESS

The subject matter doesn’t make the photograph. You do. A pure visual arrangement of nothing in particular can at least teach you composition. 1/400 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SHOOT WHAT YOU KNOW. SHOOT WHAT YOU LOVE. Those sentences seem like the inevitable “Column A” and “Column B” of photography. And it makes a certain kind of sense. I mean, you’ll make a stronger artistic connection to subject matter that’s near and dear, be it loved ones or beloved hobbies, right? What you know and what you love will always make great pictures, right?

Well….okay, sorta. And sorta not.

I hate to use the phrase “familiarity breeds contempt”, but your photography could actually take a step backwards if it is always based in your comfort zone. Your intimate knowledge of the people or things you are shooting could actually retard or paralyze your forward development, your ability to step back and see these very familiar things in unfamiliar ways.

Might it not be a good thing, from time to time, to photograph something that is meaningless to you, to seek out images that don’t have any emotional or historical context for you? To see a thing, a condition, a trick of the light just for itself, devoid of any previous context is to force yourself to regard it cleanly, without preconception or bias.

Looking for things to shoot that are “meaningless” actually might force you to solve technique problems just for the sake of solving, since the results don’t matter to you personally, other than as creative problems to be solved. I call this process “pureformance” and I believe it is the key to breathing new life into one’s tired old eyes. Shooting pure forms guarantees that your vision is unhampered by habit, unchained from the familiarity that will eventually stifle your imagination.

This way of approaching subjects on their own terms is close to what photojournalists do all the time. They have little say in what they will be assigned to show next. Their subjects will often be something outside their prior experience, and could be something they personally find uninteresting, even repellent. But the idea is to find a story in whatever they approach, and they hone that habit to perfection, as all of us can.

Just by doing something meaningless in a meaningful way.

FRAGMENTING THE FRAME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE MADE A CONSCIOUS EFFORT, IN RECENT YEARS, TO AVOID TAKING A “STRAIGHT SHOT” OUT OF, OR THROUGH A WINDOW, of using that rectangle or square as a conventional means of bordering a shot. Making a picture where a standard view of the world is merely surrounded by a typical frame shows my eye nothing at all, whereas the things that fragment that frame, that break it into smaller pieces, bisecting or even blocking information…..that’s fascinating to me.

This is not an arbitrary attempt to be “arty” or abstract. I simply prefer to build a little mystery into my shots, and a straight out-the-window framing defeats that. My showing everything means the viewer supplies nothing of his own. Conversely, pictures that both reveal and conceal, simultaneously, invite speculation and encourage inquiry. It’s more of a conversation.

Think about it like a love scene in a movie. If every part of “the act” is depicted, it’s not romantic, not sexy. It’s what the director leaves out of the scene that fires the imagination, that makes it a personal creation of your mind. Well-done love scenes let the audience create part of the picture. Showing everything is clinical….boring.

With that in mind, The Normal Eye’s topside menu now has an additional image gallery called Split Decisions, featuring shots that attempt to show what can result when you deliberately break up the normal framing in and out of windows. Some of the shots wound up doing what I wanted: others came up short, but may convey something to someone else.

As always, let us know what you think, and thanks for looking.

Related articles

- Framing Framing Framing!!! (destynimcbeth.wordpress.com)

FIND YOURSELF A KID

“MAKING PHOTOGRAPHS” IS ONLY HALF OF PHOTOGRAPHY. The other half consists of placing yourself in the oncoming path of that runaway truck Experience so that you can’t help getting run over, then trying to get the license plate of the truck to learn something from the crash. You need to keep placing your complacency and comfort in harm’s way in order to advance, to continue your ongoing search for better ways to see. Thus the role models or educational models you choose matter, and matter greatly.

Lately, much as I thrive on wisdom from the masters and elders of photography, I am relying more and more on creative energy and ideas from people who are just learning to take pictures. This may sound like I am taking driving lessons from toddlers instead of licensed instructors, but think about it a moment.

Yes, nothing teaches like experience….seasoned, life-tested experience. Righty right right. But art is about curiosity and fearlessness, and nothing says “open to possibility” like a 20-year-old hosting a podcast on what could happen “if you try this” with a camera. It is the fact that the young are unsure of how things will come out (the curiosity)  which impels them to hurry up and try something to find out (the fearlessness). Moreover, if they were raised with only the digital world as a reference point, they are less intimidated by the prospect of failure, since they are basically shooting for free and their universe is one of infinite do-overs. There is no wrong photograph, unless it’s the one you just didn’t try for.

which impels them to hurry up and try something to find out (the fearlessness). Moreover, if they were raised with only the digital world as a reference point, they are less intimidated by the prospect of failure, since they are basically shooting for free and their universe is one of infinite do-overs. There is no wrong photograph, unless it’s the one you just didn’t try for.

Best of all, photography, always the most democratic of arts, has just become insanely more so, by putting some kind of camera in literally everyone’s fist. There is no more exclusive men’s club entitlement to being a shooter. You just need the will. Ease of operation and distribution means no one can be excluded from the discussion, and this means a tidal wave of input from those just learning to love making pictures.

One joke going around the tech geek community in recent years involves an old lady who calls up Best Buy and frets, “I need to hook up my computer!”, to which the clerk replies, “That’s easy. Got a grandchild?”

Find yourself a path. Find yourself a world of influences and approaches for your photography. And, occasionally, find yourself a kid.

Related articles

- Resist the need to Get some new Camera – Change your Photography Instead (textb.wordpress.com)