DISTORTION AS DESIGN

Overhead parallels bent with a fisheye to yank the eye for forcefully into the frame, maybe impose a little claustrophobia. 1/80 sec., f/22. ISO 640, 8mm

By MICHAEL PERKINS

BORN INTO A PAINTER’S WORLD, PHOTOGRAPHY NATURALLY INHERITED THAT DISCIPLINE’S BIAS TOWARD SHOWING THE WORLD “AS IT IS“, and, in fact, the first fifty years of photographic images seem to be in a neck-and-neck race with painting for the best rendering of the world at large. Then the 20th century kind of dope-slapped humanity’s collective sense of “reality”, as a world war, the onrush of science, and the rise of secular thought combined to question what the hell we needed with reality, anyway. The arts were shaken to their foundations, and photography and painting spiraled off onto wild new side roads. All bets for what defined a “picture” were off.

That’s not to say that photography has remained visually unbound through the decades. It almost acts like the flow and ebb of the surf. Photos surge toward pure documentation, then pull back into pure effect. They roll forward into an absolute deconstruction of the real world, then clamber back into the safety of literal pictorialism. One day we’re trying to recreate a wilderness landscape with perfect fidelity; the next day we’re reducing all “subjects” moot, reducing everything to shape and light.

I have had to spend many years getting comfortable with abstractions in my photography. It’s not like I don’t have ideas that wander far from the visual mainstream. If anything, I’ve had to learn to trust those visions, to stop worrying about whether they have “value” versus some rigid, if invisible,standard. While some shooters started with an absolutely open attitude toward the camera, pointing, framing and living completely by whim or instinct (the Instagram and Lomo kids of my Stone Age), I was absolutely, unwaveringly serious about arranging or capturing things as I literally saw them. It was a very clenched approach, even if it did teach me the physics of the medium. I had to learn to hold things very tightly before learning to let anything go.

And it took a very long time.

The great gift of the digital era is that many “accounting” issues (how much film do I have left? where can I go to get these processed? do they sell my kind of film in this end of town?) are just plain gone, and, with them, a little of the constipated approach that they imposed on me. At my age, it no longer matters a damn how long I shoot, how many times I “fail”, or who does or does not choose to anoint the results. There are no teachers or parents left to show off for, no competition with anyone except myself. I am free to use surfaces as straight lines or use distortion as a design element.

The truth speaks with forked tongue: in some ways I am glad that I am no longer young, since I have finally lived long enough to “age” into my photographic niche. And it also makes me sad that I am no longer young, because I really want to run with this ball, and I realize that Time might knock my legs out from underneath me before I make it all the way down the field. Still, we are here, and here is where we have to concentrate our energy. It’s the only control we have. Or, in the words of Edna St.Vincent Millay:

My candle burns at both ends; It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends— It gives a lovely light.

THE RELENTLESS MELT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE PEOPLE YOU PHOTOGRAPH BECAUSE THEY ARE IMPORTANT. Others are chosen because they are elements in a composition. Or because they are interesting. Or horrific. Or dear in some way. Sometimes, however, you just have to photograph people because you like them, and what they represent about the human condition.

That was my simple, solid reaction upon seeing these two gentlemen engaged in conversation at a party. I like them. Their humanity reinforces and redeems mine.

This image is merely one of dozens I cranked out as I wandered through the guests at a recent reception for two of my very dearest friends. Given the distances many of us in the room traveled to be there, it’s unlikely I will ever see most of these people again, nor will I have the honor of knowing them in any other context except the convivial evening that herded us together for a time. Because I was largely eavesdropping on conversations between small groups of people who have known each other for a considerable time, I enjoyed the privilege often denied a photographer, the luxury of being invisible. No one was asked to pose or smile. No attempt was made to “mark the occasion” or make a record of any kind. And it proved to me, once more, that the best thing to relax a portrait subject is……another portrait subject.

I assume from the body language of these two men that they are friends, that is, that they weren’t just introduced on the spot by the hostess. There is history here. Shared somethings. I don’t need to know what specific links they have, or had. I just need to see the echoes of them on their faces. I had to frame and shoot them quickly, mostly to evade discovery, so in squeezing off several fast exposures I sacrificed a little softness, partly due to me, partly due to the animated nature of their conversation. It doesn’t bother me, nor does the little bit of noise suffered by shooting in a dim room at ISO 1000. I might have made a more technically perfect image if I’d had total control. Instead, I had a story in front of me and I wanted to possess it, so….

Susan Sontag, the social essayist whose final life partner was the photographer Annie Liebovitz, spoke wonderfully about the special theft, or what she called the “soft murder” of the photographic portrait when she noted that “to take a photograph is to participate in another person’s mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.”

Melt though it might, time also leaves a mark.

Caught in a box.

Treasured in the heart.

Related articles

- Susan Sontag Musings Where You Least Expect Them (hintmag.com)

THE BLUE AND THE GREY

A decent winter scene, a bit too charming in its full color original, converted in-camera to straight monochrome. Now, however, it’s too bland.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE GREAT BENEFITS OF DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY, other than its ease and affordability, is the speed at which it allows you to make comparative value judgements on images in the field. Even as digital darkrooms make it ever easier to change or modify your vision after the fact, today’s cameras also allow you to choose between several versions of a photograph while its subject is right at hand. This is an amazing mental and artistic economy, and it’s another reason why this is the absolute best time in history to be making pictures.

Many of us who made the transition from film have a lifelong habit of “bracketing”, taking multiples of the same image over a range of exposure rates to ensure that we are “covered” with at least one keeper in the batch. Others have already adopted the equivalent habit of taking several different frames with a sampling of varying white balances. I also find it helpful to use today’s in-camera filters to instantly convert color shots to three other monochrome “takes”….straight black and white, sepia and cyanotype. It’s a way to see if certain low-color subject matter will actually benefit from being reworked as duotone, and knowing that fact extra fast.

Another in-camera conversion, this time to cyanotype. This one says “winter” to me. 1/320 sec, f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

Color or its selective elimination is one of the easiest tools to wield in photography. In the case of the series shown in this post, I decided that the winter scene was a little too warm and cheery in full color, a little flat in straight B&W, but properly evocative of winter’s severity in cyan. The choice was quick, and I still had the color master shot that I could choose to massage later on.

Shooting fast, that is, at the speed of your mood or whim, is a remarkable luxury, and exploiting it to the max is easy with even the most elementary camera. And anything that converts more “maybe” shots to “yes” is my idea of a good time.

I’ll have a Blue Christmas, thank you.

Related articles

- 5 Good Photography Habits to Start Today (digital-photography-school.com)

I’M DREAMING OF A ‘CHROME CHRISTMAS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF YOU HAVE BEEN ON THE PLANET FOR MORE THAN FIFTY CHRISTMASES, your holiday memories (at least those frozen in family snapshots) will include more than a few black and white images. Some families made the switch to color photography earlier than others, but, at least until the mid-1960’s, for millions of us, more than a few “our best tree ever” photos were shot in monochrome. A little web research or family album-browsing can illustrate just how well beloved memories were captured by millions of us, long before Kodachrome became the visual currency of family folklore.

It’s interesting to note that, with the universal availability of not only simple cameras but post-processing apps, there’s been a sort of retro-fed love of b&w that’s refreshing, given that we are, once again, admitting that some subjects can be wonderfully rendered in a series of greyscale tones. Certainly the general marketing and depiction of the season is a color-drenched one, but many new photographers are re-discovering the art of doing more with less, or, more properly, seeing black and white as an interpretation of reality rather, as in the case of color, as a recording of it.

Observing the season out in the American West, thousands of miles from loved ones, I find that my holiday shots are increasingly journalistic or “street” in nature, since I am viewing and interpreting other people’s Christmases. The contours and designs of retail become a vibrant source of stories for me, and black and white allows me to shoot at an emotionally safe distance while calling special attention to texture and detail.

Depending on whether you’re showing the splendor of food and presents or evoking some Dickens-era urban grit, some subjects will come up flat or drab in black and white, given our very specific memory cues as to what Christmas should “look like”, so getting the desired result may be elusive. But, of course, if photography was easy, everyone would do it.

Oh, wait, everybody does do it.

Thing is, you always add another voice to the creative conversation. That’s the best part of both photography and the holidays.

No way is best but your way.

Related articles

- Photography 101: Shooting in Black and White (dailypost.wordpress.com)

JUST SAY THANK YOU

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PICTURES HAPPEN WHEN YOU’RE OUT TRYING TO TAKE “OTHER” PICTURES. Pictures happen when you didn’t feel like taking any pictures at all. And, occasionally, the planets align perfectly and you hold something in your hand, that, if you are honest, you know you had nothing to with.

Those are the pictures that delight and haunt. They happen on off-days, against the grain of whatever you’d planned. They crop up when it’s not convenient to take them, demanding your attention like a small insistent child tugging at your pants leg with an urgent or annoying issue. And when they call, however obtrusively, however bothersome, you’d better listen.

Don’t over-think the gift. Just say thank you….and stay open.

This is an overly mystical way of saying that pictures are sometimes taken because it’s their time to be taken. You are not the person who made them ready. You were the person who wandered by, with a camera if you’re lucky.

I got lucky this week, but not with any shot I had set out on a walkabout to capture. By the time I spotted the scene you see at the top of this post, I was beyond empty, having harvested exactly zip out of a series of locations I thought would give up some gold. I couldn’t get the exposures right: the framing was off: the subjects, which I hoped would reveal great human drama, were as exciting as a bus schedule.

I had just switched from color to monochrome when I saw him: a young nighthawk nursing some eleventh-hour coffee while poring over an intense project. Homework? A heartfelt journal? A grocery list? Who could tell? All I could see, in a moment, was that the selective opening and closing of shades all around him had given me a perfect frame, with every other element in the room diffused to soft focus. It was as if the picture was hanging in the air with a big neon rectangle around it, flashing shoot here, dummy.

My subject’s face was hidden. His true emotion or state of mind would never be known. The picture would always hide as much as it revealed.

Works for me. Click.

Just like the flicker of a firefly, the picture immediately went away. My target shifted in his chair, people began to walk across the room, the universe changed. I had a lucky souvenir of something that truly was no longer.

I said thank you to someone, packed up my gear, and drove home.

I hadn’t gotten what I originally came for.

Lucky me.

related articles:

- Crop and turn a bad picture into a good one (weliveinaflat.wordpress.com)

PLEASE PLAY WITH YOUR FOOD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHIC STILL-LIFES ARE THE POOR MAN’S PRACTICE LAB. All the necessary elements for self-taught imaging are plentiful, nearby, and generally cheap. As has been demonstrated perpetually across the history of photography, the subjects themselves are only of secondary importance. What’s being practiced are the twin arts of exposure and composition, so it doesn’t matter a pig whistle whether you’re assembling a basket of oranges or throwing together a pile of old broken Barbie dolls. It’s not about depicting a thing so much as it is about finding new ways to see a thing.

That’s why an entire class of shooters can cluster around the same randomly chosen subject and produce vastly different viewing experiences. And why one of the most commonly “seen” things in our world, for example, food, can become so intriguingly alien when subjected to the photographer’s eye.

Shooting food for still-life purposes provides remarkably different results from the professional shots taken to illustrate articles and cookbooks. “Recipe” shots are really a way of documenting what your cooking result should resemble. But other still-life shots with food quickly become a quest to show something as no one else has ever shown it. It’s not a record of a cabbage; it’s a record of what you thought about a cabbage on a given day.

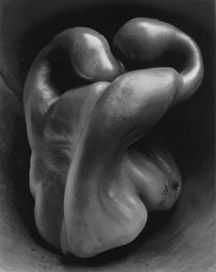

Many books over the years have re-printed Edward Weston’s famous black-and-white shots of peppers, in which some people “saw” things ranging from mountain terrain to abstract nudes. These remarkable shots are famous not for what they show, but for what they make it possible to see. Food’s various signature textures, under the photographer’s hand, suggest an infinite number of mental associations, once you visually unchain the source materials from the most common perception of their features.

As the head chef around my house, I often pick certain cooking days where I will factor in extra time, beyond what it takes to actually prepare whatever meal I’m planning. That additional time is reserved so I can throw food elements that interest me into patterns…..on plates, towels, counters, whatever, in an effort to answer the eternal photog question, is this anything? If it is, I snap it. If it’s not, I eat it (destroying the evidence, as it were).

Either way, I get what I call “seeing practice”, and, someday, when a rutabaga starts to look like a ballerina, I might be ready. Or maybe I should just lie down until the feeling passes.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

Related articles

- Is Food Art: Notes from a Food Photographer (okramagazine.org)

CUE THE CUMULUS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AMERICA’S SOUTHWESTERN STATES COME EQUIPPED WITH SOME OF THE MOST SPECTACULAR SCENERY TO BE HAD ANYWHERE ON EARTH; jutting crags, yawning canyons, vast valleys, and more sky than you’ve ever seen anywhere. Photographically, the mountains, mesas and arroyos deliver on drama pretty much year-round, while the sky can be an endless expanse of, well, not much, really. Compositionally, this means rolling the horizon line in your framing pretty far toward the top, crowding out a fairly unbroken and featureless ocean of blue….except for more humid summer months, when cloud formations truly steal the scene.

It’s true: as the storm season (sometimes called the “monsoon”, for reasons that escape me) accompanies the year’s highest temperatures in desert regions, rolling, boiling billows of clouds add texture, drama, even a sense of scale to skies in Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and California. It’s like getting free props for whatever photographic theatre you care to stage, and it often makes sense to rotate your horizon line back toward the bottom of the frame to give the sky show top billing.

Early photographers often augmented the skies in their seascapes and mountain views by layering multiple glass negatives, one containing ground features, the other crammed with “decorator” clouds. The same effect was later achieved in the darkroom during the film era. Hey, any way you get to the finish line. Suffice it to say that the harvest of mile-high cloud banks is particularly high in the desert states’ summer seasons, and can fill the frame with enough impact to render everything else as filler.

I still marvel at the monochrome masterpiece by Life magazine’s Andreas Feininger, Texaco Station, Route 66, Seligman, Arizona, 1947, which allows the sky overhead to dwarf the photo’s actual subject, creating a marvelous feeling of both space and scale. I first saw this photo as a boy, and am not surprised to see it re-printed over the decades in every major anthology of Life’s all-time greatest images. It’s a one-image classroom, as all the best pictures always are. For more on Feininger’s singular gift for composition, click the “related articles” link below.

Big Sky country yields drama all along the America southwest. And all you really have to do is point.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

Related articles

- Photography Monograph (conordoylephoto.wordpress.com)

TAKING / BRINGING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

INTELLECTUALLY, I KNOW THAT PHOTOGRAPHS DON’T NECESSARILY HAVE TO BE “ABOUT”, well, anything, but that doesn’t stop the 12-year-old photo newbie deep inside me from trying to produce images with “meaning” (yawn). Some reason to look. A subject. A story line. A deliberate arrangement of things for the purpose of communicating…something. Itchy and twitchy within my artist’s skin as I always am, I am never more out of my element than when I make a picture that is pure composition and form, a picture that has no reason to exist except that I wish it to.

As I get older, I get looser (no G.I. tract jokes about the elderly, please), and thus making what you might call “absolute” images gets easier. I just had to learn to give myself permission to do them. Unlike Atget, Brassai, and half a dozen early pioneering photographers, I don’t have to take pictures to earn my bread, so, if I capture something that no one else “gets” or likes, my children will not starve. Still, the act of making photographs that carry no narrative is far from native to me, and, if I live to be 125, I’ll probably learn to relax and really do something okay by about 93.

The process can be a head-scratcher.

The above image is an “absolute” of sorts, since I have no emotional investment whatever in the subject matter, and have nothing to reveal about it to anyone else. The arbitrary and somewhat sterile symmetry of this room, discovered during a random walk through a furniture store, just struck me, and I still cannot say why. Nor can I explain why it scores more views on Flickr over some of my more emotional work by a margin of roughly 500 to 1. A whole lot of people are seeing something in this frame, but I suspect that they are all experiencing something different. They each are likely taking vastly varied things from it, and maybe they are bringing something to it as well. Who knows what it is? Sense memory, a fondness for form or tone, maybe even a mystery that is vaguely posed and totally unresolved.

“Even though there are recognizable objects making up the arrangement, the result is completely abstract.There isn’t a “human” story to tell here, since this room has never been inhabited by humans, except for wandering browsers. It has no history; nothing wonderful or dreadful ever happened here. In fact, nothing of any kind ever happened here. It has to be form for its own sake; it has no context.

I liked what happened with the very huge amount of soft window light (just out of frame), and I thought it was best to render the room’s already muted tones in monochrome (it wasn’t a big leap). Other than that, it would be stupid to caption or explain anything within it. It is for bringers and takers, bless them, to confer meaning on it, if they can. As I said earlier, it’s always a little scary for me to let go of my overbrain when making a picture.

Then I remember this is supposed to be about feeling as well as thinking.

***Deep breath***

Next.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

Related articles

- First Critique (cohensrphotography.wordpress.com)

THE BOOK OF KODAK

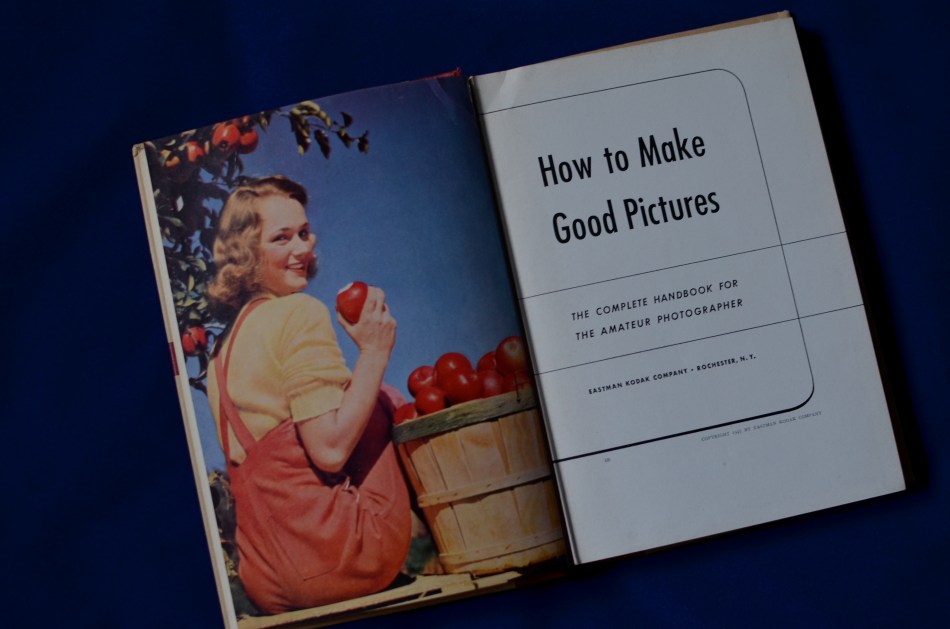

The Long-Distance Runner: The Most Successful Photography Instruction Series In History, Eastman Kodak’s How To Make Good Pictures (28th Edition,1943-47). From the collection of the author.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

KODAK’S SAD AND WOBBLY RE-EMERGENCE FROM BANKRUPTCY, announced this week, finalizes the process of “saving” a famous name, while annihilating the legacy of innovation that made that name great for over a century. Having already said goodbye to Kodachrome, most of its other trademark films, and camera production itself, Kodak will now concentrate on “imaging products”, which, for, most of us, means “printers”. Most of the news coverage of this corporate resurrection will “focus” (sorry) on what the new company stock will be worth, who goes, who stays, and a few scant mentions of the company’s original role as camera producer to the world.

That will leave a significant part of the story untold.

Certainly, George Eastman’s genius for marketing helped develop the first flexible roll films, then ingeniously created a market for them by putting a basic, usable camera in the hands of the Everyman. Nearly everyone has heard the slogan Kodak created to demonstrate how truly effortless its products had made photography: you press the button and we do the rest. But none of that would have guaranteed the company’s growth if Kodak has not also decided to become photography’s first great mass teacher, creating pro-active education programs to guarantee that, not only could Uncle Clem snap a photo easily, he could snap a good photo easily. What had once been a dark art for a select cabal of techno-wizards became, under Kodak’s outreach, something that could anybody could do.

And Kodak was going to show you how to do it.

There was a time when this Kodak Vest-Pocket Hawkeye was truly intimidating. How To Make Good Pictures made it your friend.

Beginning before the end of the Victorian era, the company began to publish the first of an endless stream of practical guides on technique and simple theory aimed at the average shutterbug. Starting in 1898 with Picture Taking And Picture Making (115 pages of tips in a cardboard cover for fifty cents!), Eastman Kodak moved to 1905’s The Modern Way In Picture Making, and, finally, to the most successful photo instruction series in history, How To Make Good Pictures, introduced in 1912 and revised continually until finishing up with its 37th edition, in 1995. Over the years the “make” in the title had been changed to “take”, and its 1890’s essays on bromide paper, collodion matte, and ground-glass focusing had evolved, over the decades, to instructions on the use of flash, color, drop-in film cartridges, and “how to tell a picture story” with your Kodacolor slides. Hundreds of printings and millions of sales later, How To Make Good Pictures forged an ironclad link between consumer and company in a way no corporation before or since has done.

To everything there is a season. Kodak’s (now historically) tragic failure to see digital photography as a viable consumer revolution, until it was too late, is a matter of raw record. The company that taught the world to see had a blind spot, a fatal one, and the irony that nearly all of the rest of the industry developed digital technology by applying processes originated (and patented) by Kodak makes the story even sadder.

But, once upon a time, the Eastman Kodak Company not only knew what the future of photography was going to look like, it wrote a handy dandy little book that told everyone how to master that future.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye

Related articles

- Kodak moments are just a memory as company exits bankruptcy (kansascity.com)

SCULPTING WITH SHADOWS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

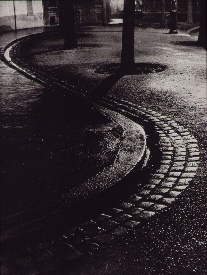

Brassai‘s world came to light at night.

ONE OF THE MIRACLES OF CONTEMPORARY PHOTOGRAPHY is how wonderfully oblivious we can afford to be to many of the mechanics of taking a picture. Whereas, in an earlier era, technical steps 1, 2, 3, 4 ,5, and 6 had to be completed before we could even hit the shutter button, we now routinely hop from “1” to “snap” with no thought of the process in between.

In short, we don’t have to sweat the small stuff, a truth that I was reminded of this week when imitating one of photographer’s earliest masters of night photography, Gyula Halasz, or “Brassai”, a nickname which refers to his hometown in Romania. Starting around 1924, Brassai visually made love to the streets of Paris after dark with the primitive cameras of the early 20th century, sculpting shape from shadow with a patiently laborious process of time exposures and creating ghostly, wonderful chronicles of a vanished world. He evolved over decades into one of the most strikingly romantic street artists of all time, and was one of the first photographers to have a show of his work mounted at New York’s MOMA.

Recently, the amazing photo website UTATA (www.utata.org), a workshop exchange for what it calls “tribal photography”, gave its visitors a chance to take their shot at an homage to half a dozen legendary visual stylists. The assignment asked Utata members to take images in the style of their favorite on the list, Brassai being mine.

In an age of limited lenses and horrifically slow films, Brassai’s exposure times were long and hard to calculate. One of his best tricks was lighting up a cigarette as he opened his lens, then timing the exposure by how long it took for the cig to burn down. He even used butts of different lengths and widths to vary his effect. Denizens of the city’s nightlife, walking through his long shots, often registered as ghosts or blurs, adding to the eerie result in photos of fogbound, rain-soaked cobblestone streets. I set out on my “homage” with a tripod in tow, ready to likewise go for a long exposure. Had my subject been less well-lit, I would have needed to do just that, but, as it turned out, a prime 35mm lens open to f/1.8 and set to an ISO of 500 allowed me to shoot handheld in 1/60 of a second, cranking off ten frames in a fraction of the time Brassai would have needed to make one. I felt grateful and guilty at the same time, until I realized that a purely technical advantage was all I had on the old wizard.

“Faux Brassai”, 2013. Far easier technically, far harder artistically. 1/60 sec., f/1.8, ISO 500, 35mm.

Brassai has shot so many of the iconic images that we have all inherited over the gulf of time that one small list from one small writer cannot contain half of them. I ask you instead to click the video link at the end of this post, and learn of, and from, this man.

Many technical land mines have been removed from our paths over photography’s lifetime, but the principal obstacle remains…the distance between head, hand, and heart. We still need to feel more than record, to interpret, more than just capture.

All other refinements are just tools toward that end.

THANKS TO OUR NEW FOLLOWERS! LOOK FOR THEM AT:

http://www.en.gravatar.com/icetlanture

http://www.en.gravatar.com/aperendu

Related articles

- Wonderful Photos of New York in 1957 by Brassaï (vintag.es)

NO CLEAR “BLACK AND WHITE” ANSWER

Hey, He’s just not that into you: In-camera monochrome, on a Nikon d5100: 1/200 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm. Street photography sometimes benefits from a limited tonal range.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SHOOTING IN BLACK AND WHITE, BEFORE THE DIGITAL ERA, WAS AN ACTIVE, RATHER THAN A PASSIVE CHOICE. You had to decide, before loading your camera, what an entire roll of film would be able to capture in terms of color/no color. There was no way to change your mind until that roll was completed and replaced. As you pre-chose film speed, light sensitivity, or special processing considerations, you also committed, before Frame One, to a single tonal option.

If you are really getting long in the tooth, you can remember when monochrome was the default choice for most of your film shoots. Economy was one factor, and, for certain shooters, including many of the pros, there was a lack of confidence that color films could render nature reliably. Giants like Adams, Edward Weston and others eschewed color throughout most of their careers, since they feared that either garish emulsions or the limits of extant printing processes would betray them in a way that black and white would not. And of course, in a world in which post-processing meant the skillful manipulation of a negative and the mastery of print-making, monochrome was simply an easier beast to tame.

Wow, are we ever in a different place.

Today, we can change our “film speed”, light sensitivity, and every kind of color emphasis frame-by-frame, and for many of us, color is our first choice, with many monochrome images post-processed from shots that were originally multi-hued. Photoshop and countless other programs allow us to have it all, with endless nuanced permutations from a single capture. Black and white is now often an “effect”, an after-thought derived later rather than sooner in our thought process. Oh, look what happens when I push this button. Cool.

Shot in color, de-saturated in post. A boring shot in color becomes super-bland when rendered in monochrome. Blame the shooter, not the mode.

Most users’ manuals for today’s cameras, especially DSLRs, actually advise converting color images to b&w in “post” rather than enabling the camera’s picture controls to shoot monochrome in the first place. The prevailing opinion seems to be that results will be better this way, since processing offers finer-tuned controls and choices, but I take issue with that, since I believe that color/no color as a choice is best made ahead of the shutter click, no less than choices about aperture or DOF. You need to be thinking about what black & white can bring to your shot (if anything) as part of your pre-shoot visualization. The tonal story in a picture is simply too important for you not to be planning it beforehand.

The quality of in-camera monochrome modes for both Nikon and Canon are both perfectly adequate to give you a workable image versus converting the shot later with software, and that’s good, because getting the shot right in the moment is better for the result than infinite knob-twiddling after the fact. Monochrome is a tool for telling a story or setting a mood. It makes sense that its use be tied to what you are trying to achieve as you are planning it….not slathering it on later as an oh-this’ll-be-keen novelty. That’s Instagram technique, not photographic technique.

One great habit to retain from the days of film: anticipate your need, and shoot according to that need. Plan ahead. “Fix it in the lab” only works for shots with slight imperfections, frames in which the concept was sound enough to warrant painting away a few flaws. Going to black and white to save an iffy shot is a Hail Mary pass at best.

As as we all know, you don’t always get what you pray for.

That’s the truth. In black and white.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

Related articles

- Capturing Texture in Black & White Photography (jdgilchristphotography.wordpress.com)

- Black and White used like Color (atmtxphoto.com)

BLUE ON THIRD AVENUE

The cyanotype option in Nikon’s monochrome posting menu makes this in-camera conversion from color easy. 1/80 sec., f/5.6, ISO 160, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

COLOR IS LIKE ANY OTHER COMPONENT IN LIGHT COLLECTION AND ARRANGEMENT, which is, really, what we are doing. Seen as a tool instead of an absolute, it’s easy to see that it’s only appropriate for some photographs. Since the explosion of color imaging for the masses seen in the coming of Kodachrome and other early consumer films in the 1930’s, the average snapper has hardly looked back. Family shots, landscapes, still life arrangements….full color or go home, right?

Well….

Oddly, professional shooters of the early 20th century were reluctant to commit to the new multi-hued media, fearing that, for some novelty-oriented photographers, the message would be the color, instead of the color aiding in the conveying of the message. Even old Ansel Adams once said of magazine editors, that, when in doubt, they “just make it red”, indicating that he thought color could become a gimmick, the same way we often regard 3-d.

In the digital age, by comparison, the color/no color decision is almost always an afterthought. There are no special chemicals, films or paper to invest in before the shutter clicks, and plenty of ways to render a color shot colorless after the fact. And now, even the post-processing steps involved in creating a monochrome image need not include an investment in Photoshop or other software. For the average shooter, monochrome post-processing is in-camera, at the touch of a button. Straight B/W and sepia and even what I call the “third avenue”, the blue duotone or cyanotype, as I’ve used above.Do such quickie options worsen the risk of gimmick-for-gimmick’s sake more than ever? As Governor Palin would say, “you betcha”. Google “over-indulgence”, or just about half of every Instagram ever taken, as evidence.

Hundreds of technical breakthroughs later, it still comes down to the original image itself. If it was conceived properly, color won’t lessen it. If it was a bad idea to start with, monochrome won’t deliver the mood or the tone changes needed to redeem it. Imagine the right image, then select the best way to deliver the message. Having quick fixes in-camera aren’t, initially, a guarantee of anything but the convenient ability to view alternatives. In the photo above, my subject was just too warm, too pretty in natural color. I thought the building itself evoked a certain starkness, a cold, sterile kind of architecture, that cyanotype could deliver far better. The shadows are also a bit more mysteriously rendered.

At bottom, the shot is just a study, since I will be using it to take far more crucial pictures of far more intriguing subjects. But the in-camera fix allows you to analyze on the fly. And, since I got into this racket to shoot pictures, and not to be a chemist, I occasionally like a fast thumbs-up, thumbs-down verdict on something I’ve decided to try in the moment.

Giving yourself the blues can be a good thing.

(follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @ mpnormaleye)

Related articles

- Toning my Cyanotype with Haritaki (altlab2011.wordpress.com)

- Beyond Color (piaffephotos.wordpress.com)