THE JOURNEY OF BECOMING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONCE MAN LEARNED TO SLICE A PATH THROUGH THE DARK WITH ANY KIND OF LIGHT, a romance with mystery began that photographers carry ever forward. Darkness and light can never be absolute, but duel with each other in a million interim stages at night, one never quite yielding to each other. A flickering lamp, a blazing torch, ten thousand LEDs, a lonely match, all shape the darkness and add the power of interpretation to the shaded side of the day. Photographers can only rejoice at the possibilities.

Spending a recent week in a vacation hotel, I fell into my typical habit of taking shots out the window under every kind of light, since, you know, you only think you understand what a view has to offer until you twist and turn it through variation. You’ve never beheld this scene before, so it’s just too easy to take an impression of it at random, leaving behind all other possibilities. The scene from this particular room, a mix of industrial and residential streets in central Pittsfield, Massachusetts, permits the viewer to see the town in the context of the Berkshire mountains, in which it nestles. Daylight, particularly early morning, renders the town as a charming, warm slice of Americana, not inappropriate in a village that is just a few miles away from the studio of painter Norman Rockwell. However, for me, the area whispered something else entirely after nightfall.

I can only judge the above frame by the combination of light and dark that I saw as I snapped it. Is it significant that the house is largely aglow while the municipal building in front of it is submerged in shadow? Is there anything in the way of mood or story that is conveyed by the lit stairs in the foreground, or the headlamps of the moving or parked cars? If the passing driver is subtracted from the frame, does the feel of the image change completely? Does the subtle outline of the mountains at the horizon lend a particular context?

That’s the point: the picture, any picture of these particular elements can only raise, not answer, questions. Only the viewer can supply the back end of the mystery raised by how it was framed or shot. Some things in the frame are on a journey of becoming, but art is not about supplying solutions, just keeping the conversation going. We’re all on our way somewhere. The camera can only ask, “what happens when we turn down this road?.”

That’s enough.

HOW MUCH IS TOO MUCH?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THESE DAYS IT SEEMS TO TAKE LESS TIME TO SNAP A PHOTOGRAPH THAN IT DOES TO DECIDE WHETHER IT HAS ANY MERIT. Photography is still largely about momentary judgements, and so it stands to reason that some are more well-conceived than others. There’s a strong temptation to boast that “I meant to do that, of course” when the result is a good one, and to mount an elaborate alibi when the thing crashes and burns, but, even given that very human tendency, some pictures stubbornly linger between keeper and krap, inhabiting a nether region in which you can’t absolutely pronounce them either success or failure.

The image at left is one such. It was part of a day spent in New York’s Central Park, and for most of the shots taken on that session, I can safely determine which ones “worked”. This one, however, continues to defy a clear call either way. Depending on which day I view it, it’s either a slice-of-life capture that shows the density of urban life or a visual mess with about four layers too much glop going on. I wish there were an empirical standard for things like photographs, but…..wait, I really don’t wish that at all. I like the fact that none of us is truly certain what makes a picture resonate. If there were such a standard for excellence, photography could be reduced to a craft, like batik or knitting. But it can never be. The only “mission” for a photographer, however fuzzy, is to convey a feeling. Some viewers will feel like a circuit has been completed between themselves and the artist. But even if they don’t, the quest is worthwhile, and goes ever on.

I have played with this photo endlessly, converting it to monochrome, trying to enhance detail in selective parts of it, faking a tilt-shift focus, and I finally present it here exactly as I shot it. I am gently closer to liking it than at first, but I feel like this one will be a problem child for years to come. Maybe I’m full of farm compost and it is simply a train wreck. Maybe it’s “sincere but just misunderstood”. I’m okay either way. I can accept it for a near miss, since it becomes a reference point for trying the same thing with better success somewhere down the road.

And, if it’s actually good, well, of course, I meant to do that.

RESTORING THE INVISIBLE

as[e The Wyandotte Building (1897), Columbus, Ohio’s first true skyscaper, seen here in a three-exposure HDR composite.

PHOTOGRAPHY IS ONE OF THE BEST RESPONSES TO THE DIZZYING SPEED OF CONTEMPORARY EXISTENCE. It is, in fact, because of a photograph’s ability to isolate time, to force our sustained view of fleeting things, that image-making is valuable as a seeing device that counteracts the mad rush of our “real time” lives. Looking into a picture lets us deal with very specific slices of time, to slowly take the measure of things that, although part of our overall sensory experience, are rendered invisible in the blur of our living.

I find that, once a compelling picture has been made of something that is familiar but unnoticed, the ability to see the design and detail of life is restored in the viewing of that thing. Frequently, in making an image of something that we are too busy to notice, the thing takes on a startlingly new aspect. That’s why I so doggedly pursue architectural subjects, in the effort to make us regard how much of our motives and ideals are captured in buildings. They stand as x-rays into our minds, revealing not only what we wanted in creating them, but what we actually created as they were realized.

In writing a book, several years ago, about a prominent midwestern skyscraper*, I was struck by how very personal these objects were…to the magnates who commissioned them, to the architects who brought them forth, and to the people in their native cities who took a kind of ownership of them. In short, the best of them were anything but mere objects of stone and steel. They imparted a personality to their surroundings.

The building pictured here, Columbus, Ohio’s 1897 Wyandotte Building, was designed by Daniel Burnham, the genius architect who spearheaded the birth of the modern steel skeleton skyscraper, heading up Chicago’s “new school” of architecture and overseeing the creation of the famous “White City” exposition of 1893. It is a magnificent montage of his ideals and vision for a burgeoning new kind of American city. As something thousand walk past every day, it is rendered strangely “invisible”, but a photograph can compensate for our haste, allowing us the luxury of contemplation.

As photographers, we can bring a particularly keen kind of witnessing to the buildings that make up our environment, no less than if we were to document the carvings and decorative design on an Egyptian sarcophagus. Architectural photography can help us extract the magic, the aims of a society, and experimenting with various methods for rendering their texture and impact can lead to some of the most powerful imagery created within a camera.

*Leveque: The First Complete Story Of Columbus’ Greatest Skyscraper, Michael A. Perkins, 2004. Available in standard print and Kindle editions through Amazon and other online bookstores.

FIGHTING TO FORGET

By MICHAEL PERKINS

STORIES OF “THE LAND THAT TIME FORGOT” COMPRISE ONE OF THE MOST RELIABLE TROPES IN ALL OF FICTION. The romantic notion of stumbling upon places that have been sequestered away from the mad forward crunch of “progress” is flat-out irresistible, since it holds out the hope that we can re-connect with things we have lost, from perspective to innocence. It moves units at the book store. It sells tickets at the box office. And it provides photographers with their most delicate treasures.

Whether our lost land is a village in some hidden valley or a hamlet within the vast prairie of middle America, we romanticize the idea that some places can be frozen in amber, protected from us and all that we create. Sadly, finding places that have been allowed to remain at the margins, that have been left alone by developers and magnates, is getting to be a greater rarity than ever before. Small towns can be wholly separate universes, sealed off from the silliness that has engulfed most of us, but just finding one which has been lucky enough to aspire to “forgotten” status is increasingly rare.

That’s why it’s so wonderful when you take the wrong road, and make the right turn.

The above stretch of sunlit houses, parallel to their tiny town’s main railroad spur, shows, in miniature, a place where order is simple but unwavering. Colors are basic. Lines are straight. This is a town where school board meetings are still held at the local Carnegie library, where the town’s single diner’s customers are on a first name basis with each other. A place where the flag is taken down and folded each night outside the courthouse. A village that wears its age like an elder’s furrowed brow with quietude, serenity.

There are plenty of malls, chain burger joints, car dealerships and business plazas within several miles of here. But they are not of here. They keep their distance and mind their manners. The freeway won’t be barreling through here anytime soon. There’s time yet.

Time for one more picture, as simple as I know how to make it.

A memento of a world fighting to forget.

THE LITTLE WALLS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

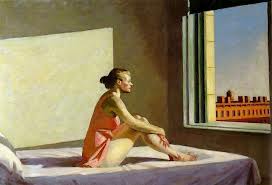

THE PAINTER EDWARD HOPPER, ONE OF THE GREATEST CHRONICLERS OF THE ALIENATION OF MAN FROM HIS ENVIRONMENT, would have made an amazing street photographer. That he captured the essential loneliness of modern life with invented or arranged scenes makes his pictures no less real than if he had happened upon them naturally, armed with a camera. In fact, his work has been a stronger influence on my approach to making images of people than many actual photographers.

“Maybe I am not very human”, Hopper remarked, “what I wanted to do was to paint sunlight on the side of a house.” Indeed, many of his canvasses fairly glow with eerily golden colors, but, meanwhile, the interiors within which his actors reside could be defined by deep shadows, stark furnishings, and lost individuals who gaze out of windows at….what? The cities in his paintings are wide open, but his subjects invariably seem like prisoners. They are sealed in, sequestered away from each other, locked by little walls apart from every other little wall.

I occasionally see arrangements of people that suggest Hopper’s world to me. Recently, I was spending the day at an art museum which features a large food court. The area is open, breathable, inviting, and nothing like the group of people in the above image. For some reason, in this place, at this moment, this distinct group of people appear as a complete universe unto themselves, separate from the whole rest of humanity, related to each other not because they know each other but because they are such absolute strangers to each other, and maybe to themselves. I don’t understand why their world drew my eye. I only knew that I could not resist making a picture of this world, and I hoped I could transmit something of what I was seeing and feeling.

I don’t know if I got there, but it was a journey worth taking. I started out, like Hopper, merely chasing the light, but lingered, to try to articulate something very different.

Or as Hopper himself said, “It you could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint”.

BRING BACK THE SHOE BOX?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS WITH MOST REVOLUTIONS, THE FAIRLY RECENT ROCKET RIDE INTO THE DIGITAL DOMAIN has created a few casualties. There simply is no way to completely transform the very act of photography without also unleashing ripples into how we view and value the images we’ve created. One of the most frequently lamented losses along these lines has to do with holding a “hard copy” picture in your hand, of having a defined physical space in which they can be easily catalogued and viewed by all. In speaking with various people about this, I sense a real emotional disconnect, a pang that can’t be satisfied by knowing that the pictures are “somewhere out there” in cyberspace. We tossed away the old family photo shoe box in all its chaos, but a key human experience was also sacrificed along the way.

If you never take the time to review the thousands of images you shoot, you lose the joy of the occasional jewels and the lessons of the near misses.

One of the consequences of the end of film is the complete banishment of numerical barriers that used to keep our photographic output at a more controllable size. A roll of film held you to 24, maybe 36 exposures. You had to budget your shots. There were no instant do-overs, no chance to shoot bursts of 60 shots of Bobby kicking the soccer ball. Now we have an overabundance of choices in shooting, which, ironically, can be a little intimidating. We can produce so many thousands of pictures in a given year that our senses simply become overwhelmed with the task of sorting, editing, or prioritizing them. Gazillions of photos go into the cloud, many unseen past the first day they are uploaded. Our ability to organize our images in any comprehensible way has not kept pace with the technology used to capture them.

I truly feel that we have to work harder than ever, not on the taking of pictures, which has become nearly intuitive in its technical ease, but on the curating of what we’ve produced. For every five hours we spend shooting, I feel that fully half that time should be spent on the careful review of everything we’ve shot, not merely the quick “like/don’t like” card shuffle many of us perform when zipping through a large batch of captures. And this is not just for we ourselves. Think about it: how can our families and friends think of our photography as a visual legacy in the way we once regarded that shoe box if they have no real appreciation of what all is even in the new, virtual equivalent of that box? If it takes us months after we do a shoot to have even a rough idea of what resulted, we are missing the occasional jewel as well as the instructive power of the many near misses. That’s having an experience without availing yourself of any idea of what it meant, and that is crazy.

There is a reason that McDonald’s only offers Coke in three serving sizes. As consumers, we really crash into paralysis when presented with too many choices. We think we want a selection consisting of, well, everything, but we seldom make use of such overwhelming sensory input. I’m a huge fan of being able to shoot as many images as you need to get what will become your precious few “keepers”. But trying to keep everything without separating the wheat from the chaff isn’t art. It isn’t even collecting.

It’s just hoarding.

THE ENNOBLING GOLD

Brooklyn Block, 2014. No, this building isn’t this pretty in “reality”. And that’s the entire point. 1/100 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LIGHT IS THE ULTIMATE MAKE-UP ARTIST, the cosmetic balm that paints warmth, softness, even a kind of forgiveness, or dignity onto the world. Photographers use light in a different way than painters, since a canvas, beginning as a complete blank, allows the dauber to create any kind of light scheme he desires. It’s a very God-like, “let there be light” position the painter finds himself in, whereas the photographer is more or less at light’s mercy, if you will. He has to channel, harness, or manage whatever the situation has provided him with, to wrangle light into an acceptable balance.

No complaints about this, by the way. There’s nothing passive about this process: real decisions are being made, and both painters and photographers are judged by how they temper and combine all the elements they use in their assembly processes. Just because a shooter works with light as he finds it, rather than brushing it into being, doesn’t make him/her any less in charge of the result. It’s just a different way to get there.

Light always has the power to transform objects into, if you will, better versions of themselves. I call it the “ennobling gold”, since I find that the yellow range of light is kindest to a wider range of subjects. Stone or brick, urban crush or rural hush, light produces a calming, charming effect on nearly anything, which is what makes managing light so irresistible to the photographer. He just knows that there is beauty to be extracted when the light is kind. And he can’t wait to grab all he can.

“Light makes photography”, George Eastman famously wrote. “Light makes photography. Embrace light. Admire it. Love it. But, above all, know light. Know it for all you are worth, and you will know the key to photography.”

Yeah, what he said.

THE FULLNESS OF EMPTY

By MICHAEL PERKINS SCIENCE TELLS US THAT SOME HUSBANDS HEAR THE QUESTION, “DID YOU TAKE THE TRASH OUT?” more often than any other phrase over the course of their married life. If you are an intrepid road warrior, you may hear more of something like “do you know where you’re going?” or “why don’t you just stop and ask for directions?”. If you’re a less than optimum companion, the most frequently heard statement might be along the lines of “and just where have you been?”. For me, at least when I have a camera in my hands, it’s always been “why don’t you ever take pictures of people?”

Why, indeed.

Of course, I contend that, if you were to take a random sample of any 100 of my photographs, there would be a fair representation of the human animal within that swatch of work. Not 85% percent, certainly, but you wouldn’t think you were watching snapshots from I Am Legend. However, I can’t deny that I have always seen stories in empty spaces or building faces, stories that may or may not resonate with everyone. It’s a definite bias, but it’s one of the closest things to a style or a vision that I have.

I think that absent people, as measured in their after-echoes in the places where they have been, speak quite clearly, and I am not alone in this view. Putting a person that I don’t even know into an image, just to demonstrate scope or scale, can be, to me, more dehumanizing than taking a picture without a person in it. My people-less photos don’t strike me as lonely, and I don’t feel that there is anything “missing” in such compositions. I can see these folks even when they are not there, and, if I do my job, so can those who view the results later.

Are such photographs “sad”, or merely a commentary on the transitory nature of things? Can’t you photograph a house where someone no longer lives and conjure an essence of the energy that once dwelt within those walls? Can’t a grave marker evoke a person as well as a wallet photo of them in happier times? I ask myself these questions, along with other crucial queries like, “what time is the game on?” or, “what do you have to do to get a beer in this place?” Some answers come quicker than others.

I can’t account for what amounts to “sad” or “lonely” when someone else looks at a picture. I try to take responsibility for the pictures I make, but people, while a key part of each photographic decision, sometimes do not need to serve as the decisive visual component in them. The moment will dictate. So, my answer to one of life’s most persistent questions is a polite, “why, dear, I do take pictures of people.”

Just not always.

THINGS ARE LOOKING DOWN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY, AND THE HABITS WE FORM IN ITS PRACTICE, BECOME A HUGE MORGUE FILE OF FOLDERS marked “sometimes this works” or “occasionally try this”, tricks or approaches that aren’t good for everything but which have their place, given what we have to work with in the moment.

Compositionally, I find that just changing my vantage point is a kind of mental refresher. Simply standing someplace different forces me to re-consider my subject, especially if it’s a place I can’t normally get to. That means, whenever I can do something easy, like just standing or climbing ten feet higher than ground level, I include it in my shooting scheme, since it always surprises me.

For one thing, looking straight down on objects changes their depth relationship, since you’re not looking across a horizon but at a perpendicular angle to it. That flattens things and abstracts them as shapes in a frame, at the same time that it’s exposing aspects of them not typically seen. You’ve done a very basic thing, and yet created a really different “face” for the objects. You’re actually forced to visualize them in a different way.

Everyone has been startled by the city shots taken from forty stories above the pavement, but you can really re-orient yourself to subjects at much more modest distances….a footbridge, a step-ladder, a short rooftop, anything to remove yourself from your customary perspective. It’s a little thing, but then we’re in the business of little things, since they sometimes make big pictures.

BEYOND THE “OWIE”

Even if the people in the picture are not drunk, desperate, or dying, it’s still street photography.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SINCE THE CAMERA IS, FIRST AND FOREMOST, A RECORDING INSTRUMENT, it has always defaulted to the function of a journalist’s device, a reportorial machine for bearing witness to events. Certainly, it was inevitable that newspapers and magazines would, over time, turn to the camera as a way of marking or defining events, of making a visual document of things. And soon, of course, that simple recording process gave way to overt commentary, to an event being imbued with as much personal bias by a photographer as had always been the case with prose writers. It was possible for the camera to have an opinion.

Street photography, which allowed the amateur to stamp his view on what he saw no less than the professional journalist, should, certainly, have developed a judgemental eye toward the tragic, the awful in life. But, as often happens, it has spawned a school of thought in which people who fancy themselves “serious” artists reflect only rotting cities or crying children. This promotes a dishonest view of the world, since, sometimes, as Elton John once wrote, “the boulevard is not that bad.” And that makes our art lopsided. I call it “photographing OWIEs” (Orphans, Winos, Idiots and Eccentrics), and it has become something of a runaway industry.

It’s a popular conceit: only dour poets are “real” poets. Only depressed writers know anything of life. And only photographers who depict abject misery really “get” the human condition. This is flawed thinking, but invariably catches hold in every “authentic” gallery exhibit, every “honest” critical essay, and every other place pretentious humans congregate to celebrate their shared gravitas.

Street photography that reflects hope, or, God spare us, even a modicum of human normalcy should never be discounted or marginalized. Artists are charged with embracing both light and shadow. And certainly, for purely scientific reasons, photographs are impossible without taking both into account.

SUBDIVISIONS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SPACE, BY ITSELF, DOESN’T SUGGEST ITSELF AS A PHOTOGRAPHIC SUBJECT, that is, unless it is measured against something else. Walls. Windows. Gates and Fences. Demarcations of any kind that allow you to work space compelling into compositions. Arrangements.

Patterns.

I don’t know why I personally find interesting images in the carving up of the spaces of our modern life, or why these subdivisions are sometimes even more interesting than what is contained inside them. For example, the floor layouts of museums, or their interior design frequently trumps the appeal of the exhibits displayed on its walls. Think about any show you may have seen within Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim museum, and you will a dramatic contrast between the building itself and nearly anything that has been hung in its galleries.

What I’m arguing for is the arrangement of space as a subject in itself. Certainly, when we photograph the houses of long-departed people, we sense something in the empty rooms they once occupied. There is fullness there inside the emptiness. Likewise, we shoot endless images of ancient ruins like the Roman Coliseum, places where there aren’t even four walls and a roof still standing. And yet the space is arresting.

In a more conventional sense, we often re-organize the space taken up by familiar objects, in our efforts to re-frame or re-contextualize the Empire State, The Eiffel, or the Grand Canyon. We re-order the space priorities to make compositions that are more personal, less popular post card.

And yet all this abstract thinking can make us twitch. We worry, still, that our pictures should be about something, should depict something in the documentary sense. But as painters concluded long ago, there is more to dealing with the world than merely recording its events. And, as photographers, we owe our audiences a chance to share in all the ways we see.

Subdivisions and all.

ASSISTANTS AND APPROACHES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHO CAN SAY WHY SOMETHING CALLS OUT TO US VISUALLY? I have marveled at millions of moments that someone else has chosen to slice off, isolate, freeze and fixate on, moments that have, amazingly, passed something along to me in their photographic execution that I would never have slowed to see in the actual world. It’s the assist, the approach, if you will, of the photographer that makes the image compelling. It’s the context his or her eye imposes on bits of nature that make them memorable, even unforgettable.

It’s occurred to me more than once that, given the sheer glut of visual information that the current world assaults us with, the greatest thing a photographer can do is at least arrest some of it in its mad flight, slow time enough to make us see a fraction of what is racing out of our reach every second. I don’t honestly know what’s more fascinating; the things we manage to freeze for further consideration, or the monstrous ocean of visual data that is lost, constantly.

There’s a reason photography has become the world’s most loved, hated, trusted, feared, and treasured form of storytelling. For the first time in human history, these last few centuries have afforded us to catch at least a few of the butterflies of our fleeting existence, a finite harvest of the flurrying dust motes of time. It’s both fascinating and frustrating, but, like spellbound suckers at a magic show, we can’t look away, even when the messages are heartbreaking, or horrible.

We are light thieves, plunderers on a boundless treasure ship, witnesses.

Assistants to the seeing eye of the heart.

It’s a pretty good gig.

FRAGMENTING THE FRAME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE MADE A CONSCIOUS EFFORT, IN RECENT YEARS, TO AVOID TAKING A “STRAIGHT SHOT” OUT OF, OR THROUGH A WINDOW, of using that rectangle or square as a conventional means of bordering a shot. Making a picture where a standard view of the world is merely surrounded by a typical frame shows my eye nothing at all, whereas the things that fragment that frame, that break it into smaller pieces, bisecting or even blocking information…..that’s fascinating to me.

This is not an arbitrary attempt to be “arty” or abstract. I simply prefer to build a little mystery into my shots, and a straight out-the-window framing defeats that. My showing everything means the viewer supplies nothing of his own. Conversely, pictures that both reveal and conceal, simultaneously, invite speculation and encourage inquiry. It’s more of a conversation.

Think about it like a love scene in a movie. If every part of “the act” is depicted, it’s not romantic, not sexy. It’s what the director leaves out of the scene that fires the imagination, that makes it a personal creation of your mind. Well-done love scenes let the audience create part of the picture. Showing everything is clinical….boring.

With that in mind, The Normal Eye’s topside menu now has an additional image gallery called Split Decisions, featuring shots that attempt to show what can result when you deliberately break up the normal framing in and out of windows. Some of the shots wound up doing what I wanted: others came up short, but may convey something to someone else.

As always, let us know what you think, and thanks for looking.

Related articles

- Framing Framing Framing!!! (destynimcbeth.wordpress.com)

FIND THE OUTLIERS

Not the kind of space you’d expect to see in a visually crowded suburban environment. And that’s the point. 1/320 sec., f/8, ISO 100, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY TIME MY WIFE AND I TRAVEL, A STRANGE PHENOMENON OCCURS. We will be standing on the exact same geographic coordinates, pointing separate cameras in generally the same general area. And, invariably when she gets her first look at the pictures I took on that day, I will hear the following:

Where was THAT? I don’t remember seeing that!? Where was I?

Of course, we see differently, as do any two shooters. Some things that are blaring red fire alarms to one of us are invisible, below the radar, to the other. And of course we are both right. And valid. Admittedly, I do seem to come back with more strange, off-to-the-side-of-the road oddities than Marian does, but that may be due more to my wildly spasmodic attention span than any real or rare “vision”. Lots of it comes because I consciously trying to overcome the numbing experience of driving in a car. I have to work harder to take notice of the unconventional when repeatedly tracking back and forth,day after day, down routine driving routes. Familiarity not only breeds contempt, it also fosters artificial blindness. The “outliers” within five miles of your own house should glow like fluorescent paint….but often they seem cloaked by a kind of habit-dulled camo.

Once detected, outliers don’t quite fit within their neighboring context. The last Victorian gingerbread home in a clutch of tract houses. The old local movie theatre reborn as a Baptist church. Or, in a place like Phoenix, Arizona, where urban development is not only unbridled but seemingly random, the rare “undeveloped” lot, crammed between more familiar symbols of sprawl.

The above image is such an outlier. It’s about an acre-and-a-half of wild trees bookended by a firehouse,

a row of ranch houses, and a busy four-lane street. Everything else on the block screams “settled turf”, while this strange stretch of twisted trunks looks like it was dropped in from some fairy realm. At least that’s what it says to me.

My first instinct in cases like this is to get out and shoot, attempting, as I go, to place the outlier in its own uncluttered context. Everything else around my “find” must be rendered visually irrelevant, since it adds nothing to the image, and, in fact, can diminish what I’m after. Sometimes I also tweak my own color mix, since natural hues also may not get my idea across.

Even after all this, I often find that there is no real revelation to be had, and I must chalk the entire thing up to practice. Occasionally, I come back with something to show my wife. And I know I have struck gold if the first thing out of her mouth is, “Where is THAT?”

To paraphrase the old proverb, behind every great man is a woman who rightfully asks, “Do you know what you’re doing?”

Sometimes I have an answer….