THE EYE BACK OF THE LENS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY YEAR AT THIS TIME, AS I HIT THE RESET BUTTON ON MY LIFE VIA SOME KIND OF BIRTHDAY RITUAL, I pause to wonder, again, whether I’ve really learned anything at all in over fifty years of photography. Surely, by this late date, the habit of shooting constantly should have assured me that I had “arrived” at some place in terms of viewpoint or style, right? And yet, I still feel as if I am just barely inches off the starting line in terms of what there is left to learn, and how much more I need to know about seeing. It’s a great feeling in that it keeps things perpetually fresh, but I often wonder if I’ll ever make it to that mirage I see ever ahead of me.

The aging process, and how that continually remaps your perception, is one of the least pondered areas of criticism as it pertains to photography. And that’s very strange. We track the evolution of technical acuity over a lifetime. We date ourselves in reference to a piece of equipment we acquired, an influential person who crossed our path, or a body of work, but we don’t thoroughly examine how much our photography is being changed completely because the person making the picture is in constant flux. How can we ignore what seems to be the biggest shaper of our vision over time? We don’t even want the same things in an image from one year to the next, so how can we take photos in our maturity anything like those we shot in our youth?

Looking back to my first images, it’s clear that I thought the mere opportunity for a picture plus the act of clicking a shutter would result in a good picture, a kind of “cool view+camera=art” equation. This is to say that, instead of thinking, “I could make a good picture from this”, I was actually thinking, “this would be a good picture.” I know that sounds like hair-splitting of the first order, but the two statements are, in fact, different. The first implies that the camera plus the subject will automatically result in something solid; it’s a snapshot philosophy. The second statement is made by someone who has been frustrated by so many snapshots that he knows he has to step into the process as an active player. That realization can only come with age.

As always, my father’s admonition that art is a process rather than a product emerges as my prime directive. When I look at the pictures made by a twelve-year old me, I can at least see what the little punk was going for, and I can measure whether I’ve gotten any closer to that ideal than he did. The trick is for old me to want it as badly as young me did, and when that happens, I forget how many candles are on the cake, and am just grateful that their light still burns brightly.

THE UNKNOWN FAMILIAR

I first photographed Jeffrey Mansion in Bexley, Ohio in the late 1960’s. I look for, and see, very different things in it now. An infusion of three exposures from 1/60-1/160 sec., all f/5.6, ISO 100, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YEARS AGO, RONALD REAGAN, UPON VISITING HIS OLD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL for a presidential photo opportunity, famously asked the local administrators how they managed to shrink the desks in the classrooms. Of course he was joking, but the remark was a telling one; when we return to the scenes of our earliest dramas and farces, we tend to believe that some other outside force sneaked into the place, before our arrival, and somehow re-ordered reality. We laugh at Reagan’s quip because we can see ourselves saying the same thing. It’s all about us.

Just as we are pleasantly shocked to view the graduated pencil marks on our old kitchen wall that logged our increasing height at different ages, we marvel when we take cameras back to the same places where we took cameras in the past. We think we are measuring time in what we shoot, but we are actually measuring ourselves in how we shoot. A recent trip to my hometown afforded me time to roll around to a number of places where I have repeatedly returned over a lifetime, each time approaching photography, and myself, a little differently. In some cases, the first frames I ever shot of these sites go back over forty years, and, good pictures or bad, the results are a few universes away from those first efforts.

How can it be otherwise? I don’t see the same way. I don’t look to see in the same way. Years ago, I was still enthralled with the idea of capturing an image in the box….any image. Hey, it worked. It’s not a stretch to say that, when I first learned to load and wind film or squint into a viewfinder, I was still amazed by the process alone, the idea of freezing time being an inexplicable miracle to me. Beyond hungering to produce my own miracles, I had no concept as to what I should be seeking, or saying.

One thing that has changed over the years is that I no longer try to stop the world with, you know, The Image. There is no “the” anymore, only “the next”. The thing I need to learn to make the picture will come, in time, if I spend long enough thinking or feeling my way through the problem. The photograph, I now know, is already in there, someplace. I just have to carve and peel until it emerges. In the images you see here, I have finally, decades hence, become ready to register the unknown in a familiar place.

To my amazement, I can actually pre-imagine a shot now, with a reasonable hope of eventually making my hand cash the check my eye has written. Back when I started, every picture was an accident….sometimes happy, often frustrating. Now, as I point my lens toward locales that are old friends, I know that they, largely, are constant. It is I who has moved. There’s some comfort, and lots of possibility, in realizing that the desks didn’t really shrink.

I just learned to stand up.

THOU SHALT….

By MICHAEL PERKINS

BOY HOWDY, DO WE LOVE LISTS. Classifications. Stratifications. Ranks. Pecking Orders. Best Of. Worst Of.

Books you need to read before you die (how could you read them otherwise?). The Ten Biggest Errors in The Phantom Menace (not counting the error in making it in the first place). Guinness Records. Pillsbury Bake-Off Finalists. The number of times Burt Ward said “Holy”-something in Batman. And, for photographers, the inevitable (and ubiquitous) lists of Most Common Photographic Mistakes.

You’ve read ’em. I’ve read ’em. We both probably have actually learned something from one or another of them. And yet, I find something strangely consistent in most of these lists; they nearly all address technical issues only. Everything from selecting the perfect depth-of-field to a kindly reminder to remove your lens cap, but very, very little about the deciding factor in all great photographs, namely, having something to say. Tech tutorials are constantly torturing themselves into tabulated commandments, all the “thou shalts”, but it is rare that the aesthetic issues, the “why shoot?” arguments, are given equal billing. This impoverishes the literature of an art that should be more about intentions and outcomes than gear or settings.

If there has been any one bonanza from the democratization of photography (through smart phones, lomography, etc), it’s been the stunning reminder that your camera doesn’t matter as much as what you can wring out of it. Eventually we’ll be able to interface with our own senses, literally taking a picture in the wink of an eye (or the sniff of a nose, if you prefer), and, with every other device used before that to freeze time, it will rise or fall with the input of the photographer’s mind/heart. If equipment was the only factor that could confer photographic greatness then only rich people would be photographers, but that is obviously not the case.

With that in mind, lists of do’s and don’ts for photographers that only focus on the technical are (1) sending the erroneous message that only the mastery of technology is necessary for great pictures, and (2) ignoring the x-factor in the human spirit that truly makes the pictures come forth. If you can obey all the “thou shalts” and still make lousy images (and you can), then you know there is something else missing.

ABSOLUTES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“PHOTOGRAPHY DEALS EXCLUSIVELY WITH APPEARANCES” remarked Duane Michals years ago, “but, nothing is what it appears to be.” That’s a remarkably clear summation of the terms under which, with greater regularity, I approach things with my camera. In over fifty years of clicking away, I have never really felt like my work was reportage, or the recording of “reality”, but rather the use of reality like another paint brush or tube of color towards the more general goal of making a picture. What I wind up with certainly “appears” like something, but it’s not really a literal representation of what I saw. It is the thing I pointed the lens at, but, if I am lucky, it’s got some other extra ingredient that was mine alone. Or so I hope.

This idea that appearances are just elements in the making of something personal seems to be borne out on those photo “field trips” where instructors take a small mob of shooters out onto the street, all of them assigned to photograph the same subject or scene. Seldom is there a consistent result as these half dozen noobs frame up a common object, a phenomenon which argues for the notion of photography as interpretation, not just the making of a visual record. Consider: if the machine really were all, every one of the students’ images should look remarkably alike, but they generally don’t. How could they, when the mystery link in every shooter’s work flow has to be the “filter” of his or her own experiences? You show how a thing appears, but it doesn’t match someone else’s sense of what it is. And that’s the divine, civil argument our vision has with everyone else’s, that contrast between my eye and your brain that allows photographs to become art.

I think that it’s possible to worry about whether your photograph “tells a story” to such a degree that you force it to be a literal narrative of something. See this? Here’s the cute little girl walking down the country lane to school with her dog. Here’s the sad old man sitting forlornly on a park bench. You can certainly make images of narrowly defined narratives, but you can also get into the self-conscious habit of trying to bend your images to fit the needs of your audiences, to make things which are easy for them to digest.Kinda like Wonder Bread for the eye.

As photographers, we still sweat the answer to the meaningless question, “what’s that supposed to be?”, as if every exposure must be matched up with someone who will validate it with an approving smile. Thing is, mere approval isn’t true connection….it’s just, let’s say, successful marketing. Make a picture in search of something in yourself, and other seekers will find it as well.

FISHING FRIDAYS?

Bandolier National Monument, New Mexico, nearly ten years and four cameras ago. Did the shot achieve everything I was seeking? Hardly. Still, it emerges now as a qualified success rather than an outright dud.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE NEVER PARTICIPATED IN THE STRANGE NEW RITUAL known as “Throwback Thursday”, the terminally adorable craze involving the online resurrection of antique photos of oneself or friends, the purpose of which is apparently to celebrate our poor tonsorial and wardrobe choices of bygone days. I keep most historic depictions of myself under lock and key for a reason, and making myself look retroactively more idiotic than I am already, well, someone needs to explain to me where the “fun” part comes in. Just because I was once stupid enough to sport a shag cut doesn’t mean a record of that sad choice constitutes entertainment in the interweb age.

As a photographer, however, I can certainly see the wisdom of re-evaluating the images themselves, meaning how they were shot, or whether, under the microscopes of time and wisdom, they deserve to be aesthetically exonerated. Humane anglers have always practiced the “throw the small ones back” rule when fishing, the idea being that, given a chance, a minnow might grow into a respectable catch, and I think it’s normal to revisit old photos from time to time, as a record of one’s growth. I would even argue that a “Fishing Friday” each week would be good for the needful habit of self-editing, or just learning to see, no less than spending one’s Thursdays with painful reminders that hot pants really aren’t a fashion statement.

Yes, I am an aging crank. And yes, I do believe, as Yogi Berra once said, that nostalgia ain’t what it used to be. But I also believe in learning from one’s photographic mistakes, and reviewing old prints and slides actually does give you a pretty reliable timeline on your development. As a matter of fact, I am on record as believing that failures are far more instructive than successes when it comes to photography. You study and ache and cogitate over failures, whereas you seldom question a success at all. Coming up short just nags at you more, and the surprising thing about latter-day re-examinations of your photographic work is that you will also find things that actually worked, shots that, for some reason, you originally rejected.

Recently, the Metropolitan Art Museum mounted a show of Garry Winogrand’s amazing street work drawn from the hundreds of thousands of images that he shot but never processed or saw within his own lifetime. His is an extreme case, but, even at our end of the craft, we generate so many photos over a lifetime that we are constantly challenged to have a true sense of what we did even last year, much less decades ago. When we “throw back” to images of our dear departed dog blowing out his birthday candles, we should also shovel into the past for the instructive, potentially revelatory work that might be lurking in other shoeboxes. It’s free education.

CAUSE AND EFFECT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE’S NOTHING WORSE THAN COMING HOME FROM A SHOOT realizing that you only went halfway on things. Maybe there was another way to light her face. Did I take a wide enough bracket of exposures on that sunset? Maybe I should have framed the doorway two different ways, with and without the shadow.

And so on. Frequently, after cranking off a few lucky frames, we’re like kids walking home from confession, feeling fine and pure at first, and then remembering, “D’OH! I forgot to tell Father about the time I sassed my teacher!”

Too Catholic? (And downright boring on the sins, by the way..but, hey) Point is, there is always one more way to visualize nearly everything you care enough about to make a picture of. For one thing, we are always shooting either the cause or the effect of things. The great facial reaction and the surprise that induces it. The deep pool of rain and the portentous sky that sent it. The force that’s released in an explosion and the origin of that force. When we’re there, when the magic of whatever we came to see is happening, right here, right now, we need to think up, down, sideways for pictures of all of it, or as many as we can capture within our power….’cause once you’re home, safe and dry, it’s all different. The story perishes like a soap bubble. Shoot while you’re there. Shoot for all the story is worth.

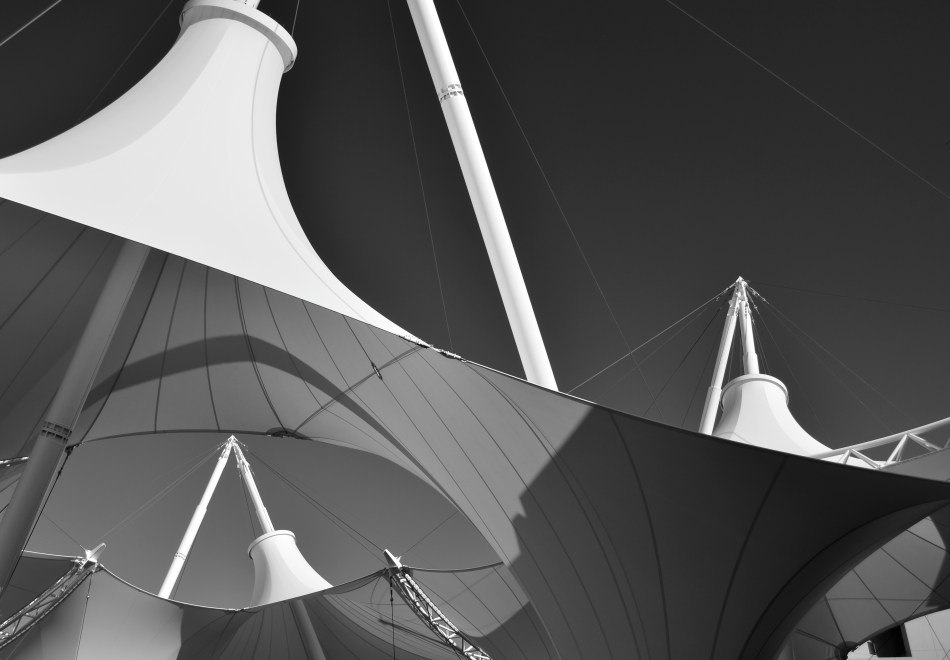

It can be simple things. I saw the above image at one of the lesser outbuildings at Taliesin West, Frank Lloyd Wright’s legendary teaching compound in Scottsdale, Arizona. An abstract pattern made from over-hanging strips of canvas,used as makeshift shade on a path. But when I reversed my angle and shot the sidewalk instead of the sky, I saw the effect of that cause, and it appealed to me too (see left). One composition favored color, while the other seemed to dictate black & white, but they both could serve my purpose in different ways. Click and click.

It bears remembering that the only picture that is guaranteed to be a failure is the one you didn’t take. Flip things around. Re-imagine the order, the role of things. Go for one more version of what’s “important”.

Hey, you’re there anyway.…..

SHOW, DON’T TALK

Got a feeling inside (can’t explain)

It’s a certain kind (can’t explain)

I feel hot and cold (can’t explain)

Yeah, down in my soul, yeah (can’t explain)—–Pete Townshend

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY NEEDS MORE ARTISTS AND FEWER ART CRITICS. Period, full stop.

When it comes to imaging, those who can, do, and those who can’t, curate shows. Or pontificate on things they had no hand in creating. It’s just human nature. Some of us build skyscrapers and some of us are “sidewalk superintendents”, peering through the security fencing to cluck our tongues in scorn, because, you know, those guys aren’t doing it right.

Even wonderful pioneers in “appreciation” like the late John Szarkowski, one of the first curators of photography at the New York Museum of Modern Art , and a tireless fighter for the elevation of photography to a fine art, often tossed up bilious bowlfuls of word salad when remarking on the work of a given shooter. As essays his remarks were entertaining. As explanations of the art, they were redundant.

This human need to explain things is vital if you’re trying to untie the knotted language of a peace treaty or complete a chemical equation, but it just adds lead boots to the appreciation of photography, which is to be seen, not read about (sassy talk for a blogger, no? Oh, well). No amount of captioning (even by the artist) can redeem a badly conceived photograph or make it speak more clearly. It all begins to sound like so many alibis, so many “here’s what I was going for” footnotes. Photography is visual and visceral. If you reached somebody, the title of the image could be “Study #245” and it still works. If not, you can append the biggest explanatory screed since the Warren Report and it’s still a lousy photo.

I’m not saying that all context is wrong in regard to a photo. Certainly, in these pages, we talk about motivation and intention all the time. However, such tracts can never be used to do the actual job of communicating that the picture is supposed to be doing. Asked once about the mechanics of his humor, Lenny Bruce spoke volumes by replying,” I just do it, that’s all.” I often worry that we use captioning to push a viewer one way or another, to suggest that he/she react a certain way, or interpret what we’ve done along a preferred track. That is the picture’s task, and if we fail at that, then the rest is noise.

THE JOY OF BEING UNIMPORTANT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE AT LEAST TWO WOMEN IN MY LIFE WHO WORRY if I am sufficiently entertained whenever I am borne along on their ventures into various holy lands of retail. Am I waiting too long? Am I bored at being brought along? Would I like to go somewhere else and rejoin them later at an appointed time and place?

Answers: No to questions 1, 2 and 3…so long as I have my hands on a camera.

I can’t tell you how many forays into shoe emporiums, peeks into vintage stores and rambles through ready-to-wear shops have provided me with photographic material, mainly because no one would miss me if I were to disappear for a bit, or for several days. And, as I catalogue some of the best pickings I’ve plucked from these random wanderings, I find that many of them were made possible by the simple question, “do you mind amusing yourself while I try this on?” Ah, to have no authority or mission! To let everything pale in importance when compared to the eager search for pictures! To be of so little importance that you are let off the leash.

The above image happened because I was walking with my wife on the lower east side of Manhattan but merely as physical accompaniment. She was looking for an address. I was looking for, well, anything, including this young man taking his cig break several stories above the sidewalk. He was nicely positioned between two periods of architecture and centered in the urban zigzag of a fire escape. Had I been on an errand of my own, chances are I would have passed him by. As I was very busy doing nothing at all, I saw him.

Of course, there will be times when gadding about is only gadding about, when you can’t bring one scintilla of wisdom to a scene, when the light miracles don’t reveal themselves. Those are the times when you wish you had pursued that great career as a paper boy, been promoted to head busboy, or ascended to the lofty office of assistant deacon. I’m telling you: shake off that doubt, and celebrate the glorious blessing of being left alone…to imagine, to dream, to leave the nest, to fail, to reach, to be.

Photography is about breaking off with the familiar, with the easy. It’s also having the luck to break off from the pack.

THE LITTLE WALLS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

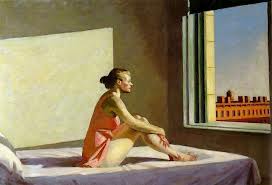

THE PAINTER EDWARD HOPPER, ONE OF THE GREATEST CHRONICLERS OF THE ALIENATION OF MAN FROM HIS ENVIRONMENT, would have made an amazing street photographer. That he captured the essential loneliness of modern life with invented or arranged scenes makes his pictures no less real than if he had happened upon them naturally, armed with a camera. In fact, his work has been a stronger influence on my approach to making images of people than many actual photographers.

“Maybe I am not very human”, Hopper remarked, “what I wanted to do was to paint sunlight on the side of a house.” Indeed, many of his canvasses fairly glow with eerily golden colors, but, meanwhile, the interiors within which his actors reside could be defined by deep shadows, stark furnishings, and lost individuals who gaze out of windows at….what? The cities in his paintings are wide open, but his subjects invariably seem like prisoners. They are sealed in, sequestered away from each other, locked by little walls apart from every other little wall.

I occasionally see arrangements of people that suggest Hopper’s world to me. Recently, I was spending the day at an art museum which features a large food court. The area is open, breathable, inviting, and nothing like the group of people in the above image. For some reason, in this place, at this moment, this distinct group of people appear as a complete universe unto themselves, separate from the whole rest of humanity, related to each other not because they know each other but because they are such absolute strangers to each other, and maybe to themselves. I don’t understand why their world drew my eye. I only knew that I could not resist making a picture of this world, and I hoped I could transmit something of what I was seeing and feeling.

I don’t know if I got there, but it was a journey worth taking. I started out, like Hopper, merely chasing the light, but lingered, to try to articulate something very different.

Or as Hopper himself said, “It you could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint”.

THINGS ARE LOOKING DOWN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY, AND THE HABITS WE FORM IN ITS PRACTICE, BECOME A HUGE MORGUE FILE OF FOLDERS marked “sometimes this works” or “occasionally try this”, tricks or approaches that aren’t good for everything but which have their place, given what we have to work with in the moment.

Compositionally, I find that just changing my vantage point is a kind of mental refresher. Simply standing someplace different forces me to re-consider my subject, especially if it’s a place I can’t normally get to. That means, whenever I can do something easy, like just standing or climbing ten feet higher than ground level, I include it in my shooting scheme, since it always surprises me.

For one thing, looking straight down on objects changes their depth relationship, since you’re not looking across a horizon but at a perpendicular angle to it. That flattens things and abstracts them as shapes in a frame, at the same time that it’s exposing aspects of them not typically seen. You’ve done a very basic thing, and yet created a really different “face” for the objects. You’re actually forced to visualize them in a different way.

Everyone has been startled by the city shots taken from forty stories above the pavement, but you can really re-orient yourself to subjects at much more modest distances….a footbridge, a step-ladder, a short rooftop, anything to remove yourself from your customary perspective. It’s a little thing, but then we’re in the business of little things, since they sometimes make big pictures.

TURN THE PAGE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’M VERY ACCUSTOMED TO BEING STOPPED IN MY TRACKS AT A PHOTOGRAPH THAT EVOKES A BYGONE ERA: we’ve all rifled through archives and been astounded by a vintage image that, all by itself, recovers a lost time.

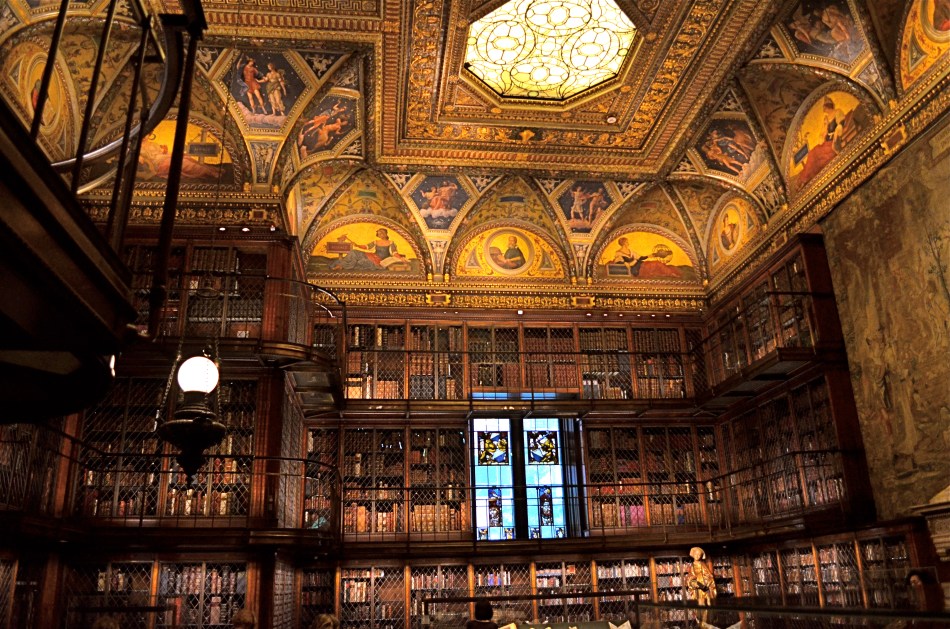

It’s a little more unsettling when you experience that sense of time travel in a photo that you just snapped. That’s what I felt several weeks ago inside the main book trove at the Morgan Library in New York. The library itself is a tumble through the time barrier, recalling a period when robber barons spent millions praising themselves for having made millions. A time of extravagant, even vulgar displays of success, the visual chest-thumping of the Self-Made Man.

The private castles of Morgan, Carnegie, Hearst and other larger-than-life industrialists and bankers now stand as frozen evidence of their energy, ingenuity, and avarice. Most of them have passed into public hands. Many are intact mementos of their creators, available for view by anyone, anywhere. So being able to photograph them is not, in itself, remarkable.

A little light reading for your friendly neighborhood billionaire. Inside the Morgan Library in NYC.

No, it’s my appreciation of the fact that, today,unlike any previous era in photography, it’s possible to take an incredibly detailed, low-light subject like this and accurately render it in a hand-held, non-flash image. This, to a person whose life has spanned several generations of failed attempts at these kinds of subjects, many of them due to technical limits of either cameras, film, or me, is simply amazing. A shot that previously would have required a tripod, long exposures, and a ton of technical tinkering in the darkroom is just there, now, ready for nearly anyone to step up and capture it. Believe me, I don’t dispense a lot of “wows” at my age, over anything. But this kind of freedom, this kind of access, qualifies for one.

This was taken with my basic 18-55mm kit lens, as wide as possible to at least allow me to shoot at f/3.5. I can actually hand-hold fairly steady at even 1/15 sec., but decided to play it safe at 1/40 and boost the ISO to 1000. The skylight and vertical stained-glass panels near the rear are WINOS (“windows in name only”), but that actually might have helped me avoid a blowout and a tougher overall exposure. So, really, thanks for nothing.

On of my favorite Twilight Zone episodes, the one about Burgess Meredith inheriting all the books in the world after a nuclear war, with sufficient leisure to read his life away, was entitled “Time Enough At Last”. For the amazing blessings of the digital age in photography, I would amend that title by one word:

Light Enough…At Last.

GOING (GENTLY) OFF-ROAD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN YOU’RE BEHIND THE WHEEL, SOME PHOTOGRAPHS NAG THEIR WAY INTO YOUR CAMERA. They will not be denied, and they will not be silenced, fairly glowing at you from the sides of roads, inches away from intersections, in unexplored corners near stop signs, inches from your car. Take two seconds and grab me, they insist, or, if you’re inside my head, it sounds more like, whatya need, an engraved invitation? Indeed, these images-in-waiting can create a violent itch, a rage to be resolved. Park the car already and take it.

Relief is just a shutter away, so to speak.

The vanishing upward arc and sinuous mid-morning shadows of this bit of rural fencing has been needling me for weeks, but its one optimal daily balance of light and shadow was so brief that, after first seeing the effect in its perfection, I drove past the scene another half dozen times when everything was too bright, too soft, too dim, too harsh, etc., etc. There was always a rational reason to drive on.

Until this morning.

It’s nothing but pure form; that is, there is nothing special about this fence in this place except how light carves a design around it, so I wanted to eliminate all extraneous context and scenery. I shot wide and moved in close to ensure that nothing else made it into the frame. At 18mm, the backward “fade” of the fence is further dramatized, artificially distorting the sense of front-to-back distance. I shot with a polarizing filter to boost the sky and make the white in the wood pop a little, then also shot it in monochrome, still with the filter, but this time to render the sky with a little more mood. In either case, the filter helped deliver the hard, clear shadows, whose wavy quality contrasts sharply with the hard, straight angles of the fence boards.

I had finally scratched the itch.

For the moment….

ASSISTANTS AND APPROACHES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHO CAN SAY WHY SOMETHING CALLS OUT TO US VISUALLY? I have marveled at millions of moments that someone else has chosen to slice off, isolate, freeze and fixate on, moments that have, amazingly, passed something along to me in their photographic execution that I would never have slowed to see in the actual world. It’s the assist, the approach, if you will, of the photographer that makes the image compelling. It’s the context his or her eye imposes on bits of nature that make them memorable, even unforgettable.

It’s occurred to me more than once that, given the sheer glut of visual information that the current world assaults us with, the greatest thing a photographer can do is at least arrest some of it in its mad flight, slow time enough to make us see a fraction of what is racing out of our reach every second. I don’t honestly know what’s more fascinating; the things we manage to freeze for further consideration, or the monstrous ocean of visual data that is lost, constantly.

There’s a reason photography has become the world’s most loved, hated, trusted, feared, and treasured form of storytelling. For the first time in human history, these last few centuries have afforded us to catch at least a few of the butterflies of our fleeting existence, a finite harvest of the flurrying dust motes of time. It’s both fascinating and frustrating, but, like spellbound suckers at a magic show, we can’t look away, even when the messages are heartbreaking, or horrible.

We are light thieves, plunderers on a boundless treasure ship, witnesses.

Assistants to the seeing eye of the heart.

It’s a pretty good gig.

DO SOMETHING MEANINGLESS

The subject matter doesn’t make the photograph. You do. A pure visual arrangement of nothing in particular can at least teach you composition. 1/400 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SHOOT WHAT YOU KNOW. SHOOT WHAT YOU LOVE. Those sentences seem like the inevitable “Column A” and “Column B” of photography. And it makes a certain kind of sense. I mean, you’ll make a stronger artistic connection to subject matter that’s near and dear, be it loved ones or beloved hobbies, right? What you know and what you love will always make great pictures, right?

Well….okay, sorta. And sorta not.

I hate to use the phrase “familiarity breeds contempt”, but your photography could actually take a step backwards if it is always based in your comfort zone. Your intimate knowledge of the people or things you are shooting could actually retard or paralyze your forward development, your ability to step back and see these very familiar things in unfamiliar ways.

Might it not be a good thing, from time to time, to photograph something that is meaningless to you, to seek out images that don’t have any emotional or historical context for you? To see a thing, a condition, a trick of the light just for itself, devoid of any previous context is to force yourself to regard it cleanly, without preconception or bias.

Looking for things to shoot that are “meaningless” actually might force you to solve technique problems just for the sake of solving, since the results don’t matter to you personally, other than as creative problems to be solved. I call this process “pureformance” and I believe it is the key to breathing new life into one’s tired old eyes. Shooting pure forms guarantees that your vision is unhampered by habit, unchained from the familiarity that will eventually stifle your imagination.

This way of approaching subjects on their own terms is close to what photojournalists do all the time. They have little say in what they will be assigned to show next. Their subjects will often be something outside their prior experience, and could be something they personally find uninteresting, even repellent. But the idea is to find a story in whatever they approach, and they hone that habit to perfection, as all of us can.

Just by doing something meaningless in a meaningful way.

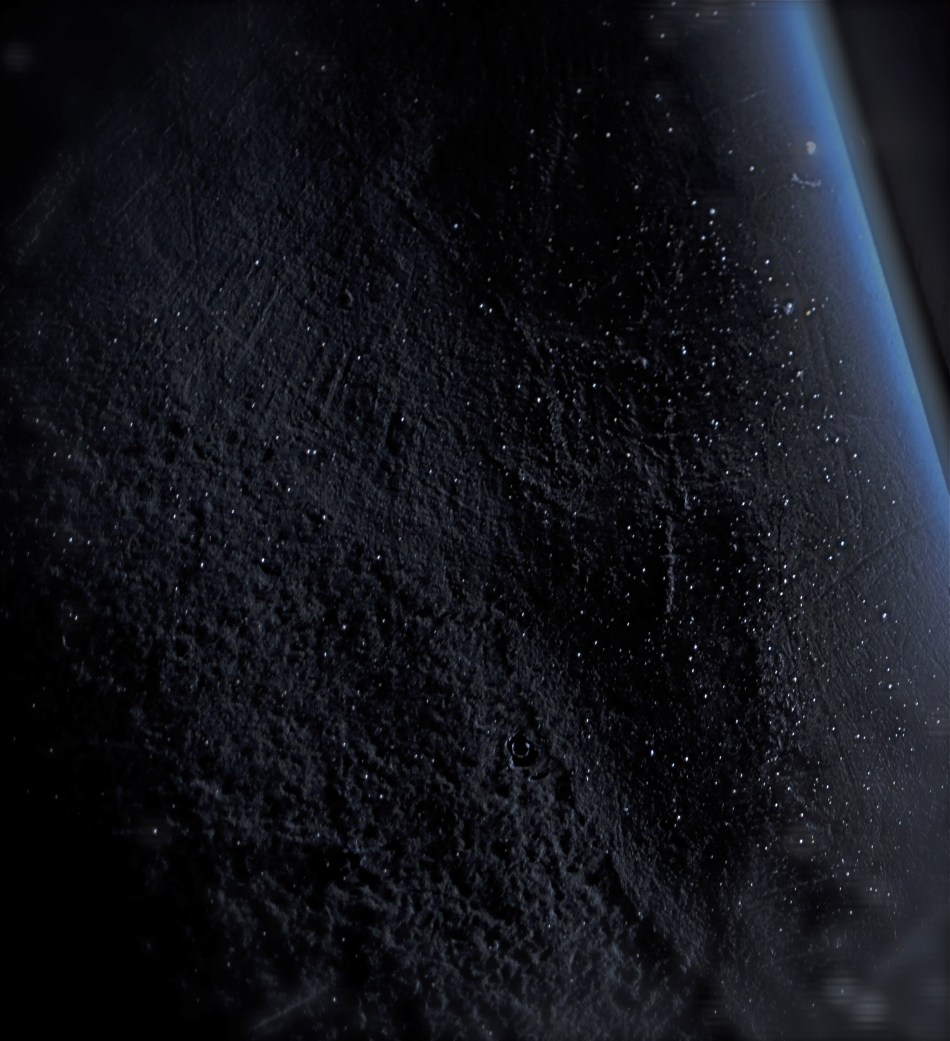

MAKING THE MIRACLES MUNDANE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

GIVEN OUR USUAL HUMAN PROPENSITY FOR USING PHOTOGRAPHY AS A LITERAL RECORDING MEDIUM, most of our pictures will require no explanation. They will be “about” something. They will look like an object or a person we have learned to expect. They will not be ambiguous.

The rest, however, will be mysteries…..big, uncertain, ill-defined, maddening, miraculous mysteries. Stemming either from their conception or their execution, they may not immediately tell anyone anything. They may ring no familiar bells. They may fail to resemble most of what has gone before. These shots are both our successes and failures, since they present a struggle for both our audiences and for ourselves. We desperately want to be understood, and so it follows that we also want our brainchildren to be understood as well. Understood…and embraced.

It cannot always be, and it should not always be.

No amount of explanatory captioning, “backstory” or rationalization can make clear what our images don’t. It sounds very ooky-spooky and pyramid- power to say it, but, chances are, if a picture worked for you, it will also work for someone else. Art is not science, and we can’t just replicate a set of coordinates and techniques and get a uniform result.

There is risk in making something wonderful….the risk of not managing to hit your mark. It isn’t fatal and it should not be feared. Artistic failure is the easiest of all failures to survive, albeit a painful kick in the ego. I’m not saying that there should never be captions or contextual remarks attached to any image. I’m saying that all the verbal gymnastics and alibis in the world won’t make a space ship out of a train wreck.

The above image is an example. If this picture does anything for you at all, believe me, my explanation of how it was created will not, repeat, not enhance your enjoyment of it one particle. Conversely, if what I tried is a swing and a miss, in your estimation, I will not be able to spin you a big enough tale to see magic where there is none. I like what I attempted in this picture, and I am surprisingly fond of what it almost became along the way. That said, I am perfectly fine with you shrugging your shoulders and moving on to the next item on the program.

Everything is not for everybody. So when someone sniffs around one of your photographs and asks (brace for it), “What’s that supposed to be?”, just smile.

And keep taking pictures.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

Related articles

- Weakness as Potential Strength (munchow.wordpress.com)

- Hidden Surprises in the Mundane (piconomy.wordpress.com)