AVOIDING THE BURN

AS A PHOTOGRAPHER, YOU CAN EMPATHIZE WITH THAT FAMOUS MOTH AND HIS FATAL FASCINATION with a candle flame….especially if you’ve ever flirted too close to the edge of a blowout with window light. You want to gobble up as much of that golden illumination as possible without singeing your image with a complete white-hot loss of detail. Too much of a good thing and all that.

However, a window glowing with light is one of the most irresistible of candies for a shooter, and you can fill up a notebook with attempted end-arounds and tricks to harvest it without getting burned. Here’s one cheap and easy way:

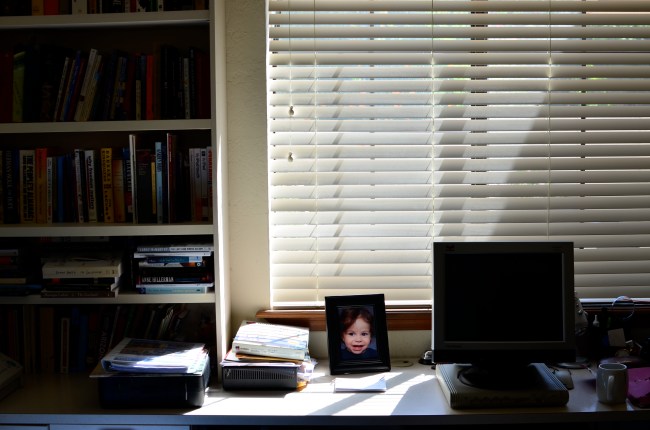

In this first attempt to capture the early morning shadows and scattered rays in my office at 1/100 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, you’ll see that the window is a little too hot, and that nearly everything ahead of the window is rendered into a silhouette. And that’s a shame, since the picture, to me, should be not only about the window light, but also its role in partially lighting a dark room. I don’t want to make an HDR here, since that will completely over-detail the stuff in the dark and look un-natural. All I really need is a hint of room light, as if a small extra bit of detail has been illuminated by the window, but just that….a small bit.

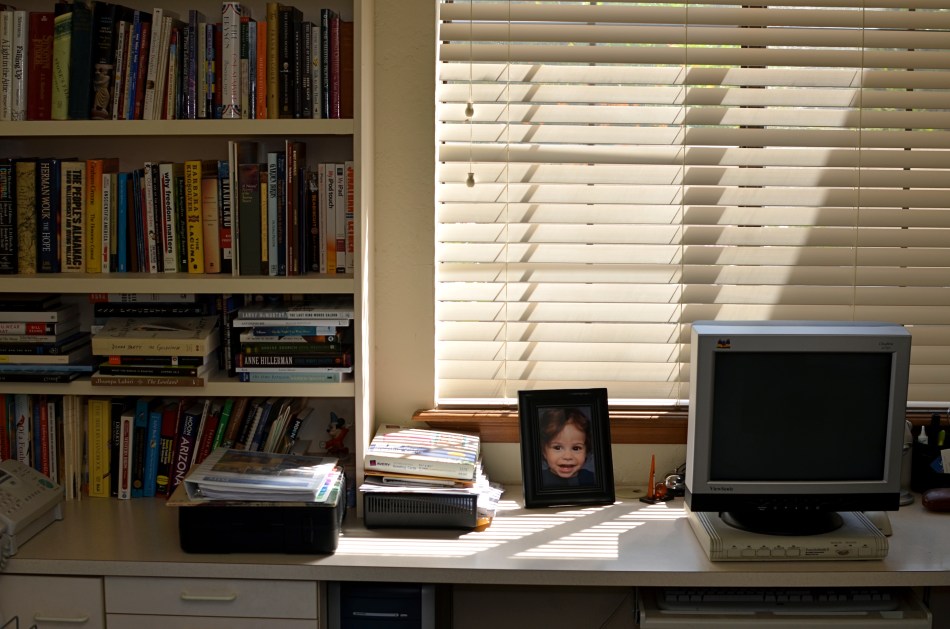

In the second attempt, I have actually halved the shutter speed to 1/200 to underexpose the window, but have also used my on-camera flash with a bounce card to ricochet a little light off the ceiling. I am almost too far away for the flash to be of any real strength, but that’s exactly what I’m looking for: I want just a trace of it to trail down the bookshelf, giving me some really mild color and allowing a few book titles to be readable. The bounce plus the distance has weakened the flash to the point that it plausibly looks as if the illumination is a result of the window light. And since I’ve underexposed the window, even the wee bit of flash hasn’t blown out the slat detail from the blinds.

Overall, this is a cheap and easy fix, happens in-camera, and doesn’t call attention to itself as a technique. There are two kinds of light: the light that is natural and the light that can be made to appear natural. If you can make the two work smoothly together, you can fly close to the flame while avoiding the burn.

THE FULLNESS OF EMPTY

By MICHAEL PERKINS SCIENCE TELLS US THAT SOME HUSBANDS HEAR THE QUESTION, “DID YOU TAKE THE TRASH OUT?” more often than any other phrase over the course of their married life. If you are an intrepid road warrior, you may hear more of something like “do you know where you’re going?” or “why don’t you just stop and ask for directions?”. If you’re a less than optimum companion, the most frequently heard statement might be along the lines of “and just where have you been?”. For me, at least when I have a camera in my hands, it’s always been “why don’t you ever take pictures of people?”

Why, indeed.

Of course, I contend that, if you were to take a random sample of any 100 of my photographs, there would be a fair representation of the human animal within that swatch of work. Not 85% percent, certainly, but you wouldn’t think you were watching snapshots from I Am Legend. However, I can’t deny that I have always seen stories in empty spaces or building faces, stories that may or may not resonate with everyone. It’s a definite bias, but it’s one of the closest things to a style or a vision that I have.

I think that absent people, as measured in their after-echoes in the places where they have been, speak quite clearly, and I am not alone in this view. Putting a person that I don’t even know into an image, just to demonstrate scope or scale, can be, to me, more dehumanizing than taking a picture without a person in it. My people-less photos don’t strike me as lonely, and I don’t feel that there is anything “missing” in such compositions. I can see these folks even when they are not there, and, if I do my job, so can those who view the results later.

Are such photographs “sad”, or merely a commentary on the transitory nature of things? Can’t you photograph a house where someone no longer lives and conjure an essence of the energy that once dwelt within those walls? Can’t a grave marker evoke a person as well as a wallet photo of them in happier times? I ask myself these questions, along with other crucial queries like, “what time is the game on?” or, “what do you have to do to get a beer in this place?” Some answers come quicker than others.

I can’t account for what amounts to “sad” or “lonely” when someone else looks at a picture. I try to take responsibility for the pictures I make, but people, while a key part of each photographic decision, sometimes do not need to serve as the decisive visual component in them. The moment will dictate. So, my answer to one of life’s most persistent questions is a polite, “why, dear, I do take pictures of people.”

Just not always.

A SQUARE DEAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I WAS AT THE MORGAN LIBRARY IN NEW YORK earlier this week, combining a museum tour with a photo shoot, when I came upon an exhibit which featured one of the earliest Kodak consumer prints, with the image contained inside a circle, rather than the rectangular frames most of us remember. It reminded me that the very formatics of picture-making were, for a long time, dictated by the physical dimensions of either camera or film, and that, suddenly, we are free to make photographs of any proportions we choose, anytime, everytime.

It’s really an amazing liberation, and, as an ironic consequence, some photographers are choosing to return to the framing formats that they used to decry as too limiting, subjecting themselves to the extra discipline of staying within a boundary and adjusting their compositional priorities thusly. This has made for a kind of revival of the square image, and there seem to be some distinct advantages to the trend.

Shooting on the square means calling attention to the center of an image, to using symmetry to your advantage, and to paring your composition to its bare essentials. The negative space used in landscape or portrait modes can still work within a square image, but the subject, and your use of it, must be just right. Squaring off means calling immediate attention to your message, and making it all the stronger, since there’s nowhere else for the eye to go.

Andrew Gibson, writing for the website Digital Photography School, explains the visual appeal of the square:

Using the square format encourages the eye to move around the frame in a circle. This is different from the rectangular frame, where the eye is encouraged to move from side to side (landscape format) or up and down (portrait format). The shape of the frame is a major factor.

It’s odd to think of freeing up your photography by voluntarily working within a more restrictive format. And, unlike the old days of square-only shooting, the effect is largely created “after the click”, by re-composing through creative cropping. But the additional mindfulness can really boost the power of your images.

BREAKING THE BIG RULE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FACES ARE THE PRIMARY REASON THAT PHOTOGRAPHY FIRST “HAPPENED” FOR MOST OF US. Landscapes, the chronicling of history, the measurements of science, the abstract rearrangement of light, no other single subject impacts us on the same visceral level as the human countenance. Its celebrations and tragedies. Its discoveries and secrets. Its timeline of age.

It is in witnessing to faces that we first learn how photography works as an interpretive art. They provide us with the clearest stories, the most direct connection with our emotions and memories. And the standard way to do this is to show the entire face. Both eyes. Nose. Mouth. The works. Right?

But can’t we add both interpretation and a bit of mystery by showing less than a complete face? Would Mona Lisa be more or less intriguing if her eyes were absent from her famous portrait? Would her smile alone convey her mystic quality? Or are her eyes the sole irreplaceable element, and, if so, is her smile superfluous?

Instead of faces as mere remembrances of people, can’t we create something unique in the suggestion of people, of a faint ghost of their total presence” Can’t images convey something beyond a mere record of their features on a certain day and date? Something universal? Something timeless?

It seems that, as soon as we maintain rigidity on a rule….any rule…we are likewise putting a fence around how far we can see. The face is no more sacred than any other visual element we hope to shape.

Let’s not build a cage around it.

FALL-OFF AS LEAD-IN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

USING “LEADING LINES” TO PULL A VIEWER INTO AN IMAGE IS PRETTY MUCH COMPOSITION 101. It’s one of the best and simplest ways to overcome the flat plane of a photograph, to simulate a feeling of depth by framing the picture so the eye is drawn inward from a point along the edge, usually by use of a bold diagonal taking the eye to an imagined horizon or “vanishing point”. Railroad tracks, staircases, the edge of a long wall, the pews in a church. We all take advantage of this basic trick of engagement.

Bright light into subdued light: a natural way to pull your viewer deeper into the picture. 1/100 sec., f/1.8, ISO 650, 35mm.

One thing that can aid this lead-in effect even more is shooting at night. Artificial lighting schemes on many buildings “tell” the eye what the most important and least important features should be…where the designer wants your eye to go. This means that there is at least one angle on many city scenes where the light goes from intense to muted, a transition you can use to seize and direct attention.

This all gives me another chance to preach my gospel about the value of prime lenses in night shots. Primes like the f/1.8 35mm used for this image are so fast, and recent improvements in noiseless ISO boosts so advanced, that you can shoot handheld in many more situations. That means time to shoot more, check more, edit more, get closer to the shot you imagined. This shot is one of a dozen squeezed off in about a minute. The reduction of implementation time here is almost as valuable as the speed of the lens, and, in some cases, the fall-off of light at night can act as a more dramatic lead-in for your shots.

ALIENATIONS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE STRANGEST VISUAL EVIDENCE OF MAN’S PRESENCE ON THE PLANET IS HIS ABILITY TO COMPARTMENTALIZE HIS THINKING, the ability to say, of his living patterns, “over here, cool. Over there, six inches away, ick. You see these kind of yes/no, binary choices everywhere. The glittering, gated community flanked by feral urban decay. The open pasture land that abuts a zoo. And the natural world, trying desperately to be heard above the roar of its near neighbors from our co-called “civilization”.

As seen from Griffith Observatory: park running paths and a smog-shrouded L.A. 1/320 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

I recently re-evaluated this image of the running paths at Los Angeles’ Griffith Park and the nearby uber-grid of the central city. The colors are a bit muted since it was taken on a day of pretty constant rolling overcast, and it really is not a definitive portrait of either the city or the nearby greenspace, but there is a little story to be told in the ability of the two worlds to co-exist.

L.A’s lore is rife with stories of destroyed environments, twisted eco-structure, bulldozed neighborhoods and political hackery advanced at great cost to the poor and the powerless. In the face of that history, the survival of Griffith, a 4,310-acre layout of parks, museums, kiddie zoos, sports courts, and concert venues on the eastern end of the Santa Monica Mountains, is something of a miracle. It’s the lion lying down with the lamb, big-time, a strange and lucky juxtaposition that affords some of the most interesting fodder for photographers anywhere in California. Photogs observe natural pairings in the world, but they also chronicle alienations, urban brothers from different mothers, tales of visual conflicts that, while they can’t be reconciled, are worth noting.

GET THEE TO A LABORATORY

by MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHIC SUBJECT MATTER, ONCE YOU’VE TRAINED YOURSELF TO SPOT IT, is always in ready supply. But, let’s face it: many of these opportunities are one-and-done. No repeats, no returns, no going back for another crack at it. That’s why, once you learn to make pictures out of almost nothing, it’s like being invited to a Carnival Cruise midnight buffet to find something that is truly exploding with possibilities, sites that actually increase in artistic value with repeat visits. I call such places “labs” because they seem to inspire an endless number of new experiments, fresh ways to look at and re-interpret their basic visual data.

My “labs” have usually been outdoor locations, such as Phoenix’ Desert Botanical Gardens or the all-too-obvious Central Park, places where I shoot and re-shoot over the space of many years to test lenses, exposure schemes, techniques, or, in the dim past, different film emulsions. Some places are a mix of interior and exterior and serve purely as arrangements of space, such as the Brooklyn Museum or the Library of Congress, where, regardless of exhibits or displays, the contours and dynamics of light and form are a workshop all in themselves. In fact, some museums are more beautiful than the works they house, as in the case of Guggenheim in NYC and its gorgeous west coast equivalent, The Getty museum in Los Angeles.

No color? No problem. Interior view of the Getty’s visitor center. 1/640 sec., f/5.6. ISO 100, 35mm.

Between the gleaming white, glass-wrapped buildings of this enormous arts campus and its sinuous, sprawling gardens (not to mention its astounding hilltop view), the Getty takes one complete visit just to get yourself visually oriented. Photographically, you will find a million isolated tableaux within its multi-acre layout upon subsequent trips, so there is no end to the opportunities for exploring light, scale, abstraction, and four full seasons of vibrant color. Not a color fan? Fine. The Getty even dazzles in monochrome or muted hues. It’s like Toys ‘R’ Us for photogs.

I truly recommend laying claim to a laboratory of your own, a place that you can never truly be “finished with”. If the place is rich enough in its basic components, your umpteenth trip will be as magical as your first, and you can use that one location as a growth graph for your work. Painters have their muses. Shooter Harry Calahan made a photographic career out of glorifying every aspect of his wife. We all declare our undying love for something.

And it will show in the work.

THEY HAD FACES THEN

Happy Shining Houses: Two copies of the same image, balanced in Photomatix’ Tone Compression algorithm.1/1000 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST HORRIBLE CONSEQUENCES OF SUBURBAN SPRAWL, beyond the obscene commercial eye pollution, the devastation of open space, and the friendless isolation, is the absolute soulless-ness of the places we inhabit. The nowheres that we live in are everywhere. Wherever you go, there you are. Move three miles and the cycle has repeated. Same Shell stations, same Wal-Marts, same banal patterns.

The title of a classic book on the passing of the star era of Hollywood could also be the story of the end of the great American house: They Had Faces Then.

I believe that the best old houses possess no less a living spirit than the people who live inside them. As a photographer, I seek out mish-mosh neighborhoods, residential blocks that organically grew over decades without a “master plan” or overseeing developer. Phoenix, Arizona is singular because, within its limits, there are, God knows, endless acres of some of the most self-effacing herdblocks created by the errant hand of man, but also some of the best pre-WWII neighborhoods, divine zones where houses were allowed to sprout, erupt, and just happen regardless of architectural period, style, or standard. It is the wild west realized in stucco.

When I find these clutches of houses, I don’t just shoot them, I idealize them, bathing the skies above them in azure Kodachrome warmth, amping up the earth tones of their exteriors, emphasizing their charming symmetries. Out here in the Easy-Bake oven of the desert, that usually means a little post-production tweaking with contrasts and colors, but I work to keep the homes looking as little like fantasies and as much like objects of desire as I can.

One great tool I have found for this is Photmatix, the HDR software program. However, instead of taking multiple exposures and blending them into an HDR, I take one fairly balanced exposure, dupe it, darken one frame, lighten the other, and process the final in the Tone Compression program. It gives you an image that is somewhat better than reality, but without the Game of Thrones fantasy overkill of HDR.

Photography is partly about finding something to shoot, and partly about finding the best way to render what you saw (or what you visualized). And sometimes it’s all about revealing faces.

SHARED JOURNEYS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE CAN’T BE A SINGLE PHOTOGRAPHIC ARTIFACT ELOQUENT ENOUGH to speak to all the human experiences of a mass migration, so any attempt of mine or others to sum up the journey of the Irish in even a series of images will be doomed to, if not failure, the absence of many voices. Those who prayed and went unheard. Those who leaped only to vanish into the air. Those who had their souls and stomachs starved to make freedom more than an abstraction. Those who kept faith and those who lost their way.

America continues, on this St. Patrick’s Day, to struggle with the issue of who is welcome and who is “the other”, so the trek of the Irish from despised newcomers to an interwoven thread in the national fabric should be seen as a template. See, we should be saying to the newcomers, it can be done. You can arrive to jeers, survive through your tears, thrive in your cheers. Wait and work for justice. Take your place in line, or better yet, insist on a place in line, a voice in the conversation. The country will come around. It always has.

For the Irish, arrival in America begins in a time of gauzy memory and oral histories, then blends into the first era of the photograph and its miraculous power to freeze time. And when all the emerald Budweiser flowing on this day has long since washed away, the Irish diaspora will still echo in the collective images of those who first crossed, those who said an impossible, final farewell to everything in the hope of everything else, and those who stepped before a camera.

In some families the histories are blurred, fragmented. In some attics and scrapbooks, the faces are missing. The recent American love affair with geneology has triggered a search for the phantoms within families, the notes absent from the song, and this has coaxed some of the images out of the shadows. So that’s what she looked like, we say. Oh, you have his eyes. We still have that hat up in the attic. I never knew. I never dreamed.

One thing that can help, in all families, whatever their journeys to this place, is to bear witness with cameras. To save the faces, to fix them in time. To research and uncover. Another is to recall what it felt like to be “the other”, and to extend a hand to those who presently bear that painful label.

So, today, my thanks to the O’Neills, Doodys, McCourts, Sweeneys and others who got me here. Due to the ravages of time, I may not have the luxury of holding your faces in my hand.

But nothing can erase your voices from my heart.

HOW DARE HUE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S TRULY AMAZING TO CONSIDER THAT, AS RECENTLY AS THE LATE 1940’s, many serious photographers were, at best, indifferent to color, and at worst, antagonistic toward its use in their work. And we’re talking Edward Weston, Ansel Adams and many other big-shoulders guys, who regarded color with the same anxiety that movie producer experienced when silent segued to sound. We’re talking substantial blood pressure issues here.

Part of the problem was that black and white, since it was not a technical representation of the full range of hues in nature, was already assumed to be an interpretation, not a recording, of life. The terms between the artist and the audience were clear: what you are seeing is not real: it is our artistic comment on real. Color was thought, by contrast, to be “merely” real, that is to say limiting, since an apple must always be red and a blueberry must always be blue. In other words, for certain shooters, the party was over.

There were also technical arguments against color, or at least the look of color as seen in the printing processes of the early 20th century. Mass-appeal magazines like Look, Life, and National Geographic had made, in the view of their readers, massive strides in the fidelity of the color they put on newsstands. For Adams, these advances were baby steps, and pathetic ones at that, leading him and others to keep their color assignments to a bare minimum. In Adams’ case in particular, color jobs paid the bills that financed the black and white work he thought to be more important, so, if Kodak came calling, he reluctantly returned their calls. He then castigated his own color work as “aesthetically inconsequential but technically remarkable.”

Look where we are today, making color/not color choices in the moment, without changing films in mid-stream, deciding to convert or de-saturate shots in camera, in post processing, or even further down the road, based on our evolving view of our own work.

There are times when I still prefer monochrome as more “trustworthy” to convey a story with a bit more grit or to focus attention on textures instead of hues. In the above shot, I decided that the spare old building and its spidery network of power meters simply had more impact without the pretty colors from its creative makeover. However, one of my color frames was stronger compositionally than the black and white, so I desaturated it after the fact. Fortunately, I had shot with a polarizing filter, so at least the tonal range survived the transition.

The miracle of now is that we can make such microscopic tweaks in our original intention right on the spot. And that’s good, since, when it comes to color, nothing is ever black and white (sorry).

SOME OF MY BEST FRIENDS ARE (NOT) PHOTOGRAPHERS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE WAS A BRIEF MOMENT, WHEN PHOTOGRAPHY WAS A NOVELTY, when it was thought to be in some kind of winner-take-all death match with painting. That fake war lasted but a moment, and the two arts have fed (and fed upon) each other to varying degrees ever since. Both painting and photography have passed through phases where they were consciously or unconsciously emulating each other, and I dare say that all photographers have at least a few painter’s genes in their DNA. The two traditions just have too much to offer to live apart.

One of my favorite examples of “light sculpting”, the artistic manipulation of illumination for maximum mood, came to me not from a photographer, but from one of the finest illustrators of the early twentieth century. Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966) began his career as a painter/illustrator for fanciful fiction from Mother Goose to The Arabian Nights. Then, as color processes for periodicals became more sophisticated after 1900, he seamlessly morphed into one of the era’s premier magazine artists, working mostly for ad agencies, and most famously for his series of magnificently warm light fantasies for Edison Mazda light bulbs.

Parrish’s Mazda ads are dazzling arrangements of pastel blues, golden earth tones, dusky oranges, and hot yellows, all punched up to their most electrically fantastic limits. Years before photographers began to write about “golden hours” as the prime source of natural light, Parrish was showing us what nature seldom could, somehow making his inventions seem a genuine part of that nature. The stuff is mesmerizing. See more of his best at: http://www.parrish.artpassions.net/

During a recent trip to the high walking paths that crown Griffith Park in Los Angeles, I saw the trees and hills, at near sunset, form the perfect radiated glow of one of Parrish’s dusks. Timing was crucial: I was almost too late to catch the full effect, as shadows were lengthening and the overhanging tree near my cliffside lookout were beginning to get too shadowy. I hoped tha,t by stepping back just beyond the effective range of my on-board flash, I could fill in the front of the fence, allowing the light to decay and darken as it went back toward the tree. Too close and it would be a total blowout. Too far back, and everything near at hand would be too dark to complement the color of the sky and the hills.

After a few quick adjustments, I had popped enough color back into the foreground to make a nice authentic fake. For a moment, I was on one of Parrish’s mountain vistas, lacking only the goddesses and vestal virgins to make the scene complete. You’d think that, this close to Hollywood, you could get Central Casting to send over a few extras. In togas.

Next time.

POST No. 200: LET’S SEE WHAT HAPPENS

Let There Be (A Way To Catch) Light: The Imperial Mark XII, my first camera. 1/200 sec., f/5.6, ISO 125, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

TIME, AT MY LOCATION IN LIFE, NOW PROCEEDS LIKE A CRUISE MISSILE, OR FASTER. Some days the signposts are zipping by so quickly that I seem to be inside a blender going full tilt puree.

I began THE NORMAL EYE as a kind of “let’s see what happens” project in 2012. Back at the starting line, 200 posts ago today, I wondered if I could even get to 200 words. Then a lucky accident occurred. Photography, which, over a lifetime has been an unfailing miracle of discovery for me, willed that passion onto my pages. Maybe it’s the kind of writing that is available to me, to all of us, as a unique feature of the present world. Maybe I had to live this long to become a chronicler for my eye and the soul that stands behind it.

As a broadcaster, I made my living for over thirty years writing advertising copy, news features, presentations, columns and tutorial material, but always for someone else, always to other agendas beyond my own. But, even while I was working for everyone else but myself, photography served as one of the very few constants in my life, and one of its principal sources of joy. Happy problem: I feel like I need another whole life to try to realize what I can now visualize. If I have any regret, it is that I learn everything the hard way, the slow way, experientially. If I could conceptualize the finer points of the art of imaging without running it personally through my own fingers, I would. It would save time, a premium item at any age, but beyond price from where I stand now.

When I first began clicking away as a kid with a kamera, I knew nothing but that I wanted to make pictures. I was divinely unaware of how truly ignorant I was and keen for the fray. My father, being a graphic artist, subscribed to Life magazine when it was still the premier photo newsmagazine in the world, tearing out the images in every issue and organizing them into a morgue file. There was the world in our garage, alphabetized as a ready reference on any subject. Want to know how to draw a giraffe? Look in the G folder.

But something else was happening as well. I was getting a crash course from the leading photographers on the planet as to how to see, how to show what you saw, how to make others see. I had my own version of the twelve apostles in the works of Alfred Eisenstadt, Gordon Parks, Larry Burrows, Richard Avedon, Otto Karsh, Margaret Bourke-White, and a half dozen others. Inside this special Bible I studied chapters and verses from the books of Aperture, F-stop, Exposure, Tri-Pan X, Graphlex. Praise the Lord and pass the polarizing filter.

As photographers, we all know that our favorite picture is the one we haven’t taken yet, since therein lies the potential for everything. I have to approach this blog the same way. Your input and my impatience have both fueled the fun and the fury of THE NORMAL EYE, and I hope to continue the affair as far as it will take us. I can’t focus for infinity, since I don’t know how far away that is. But, with your help, I can definitely manage 200 words at a time.

Thanks for coming here.

ORPHANS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF YOU SHOOT ALL THE TIME, NEARLY EVERY DAY, THE SHEER TONNAGE of what you bring home guarantees that you will inevitably lose track of a large portion of your total output. Being that your alloted daily attention span is a finite number, you will literally run out of time before you can lavish affection on everything you’ve captured, on any occasion. Some shots will jump into your car like eager puppies, panting “take me home”, while others will be orphaned, tossed into the vast digital shoebox marked “someday”, many never seeing the light of day again.

The cure for this, oddly, lies in the days when no ideas emerge and no pictures are taken…the dreaded “drys”, those horrible, slow periods when you can’t buy an inspiration to save your life. In those null times, the intellectual equivalent of a snow day, you may find it useful to revisit the shoebox, to rescue at least a shot or two formerly consigned to the shadows.

Using your paralysis periods for reflection may get you off the creative dime (and it may not), but it will, at least, allow you to approach old experiments with a fresh eye, one seasoned by time and experience. Maybe you overlooked a jewel in your haste. You almost certainly left free lessons on either technique or humility by the wayside, wisdom that can be harvested now, since you’re currently watching your camera mock you from across the room (okay, mock is harsh).

During my last visit to Manhattan, I was determined to explore the limits of natural light streaming from the gigantic windows of the main terminal floor at Grand Central, and, for the most part, I framed the place’s architectural features in such a way as to dwarf the scurrying humanity heading to their various destinations. I did shoot a few floor shots as “crowd pieces”, but, upon editing, I failed to look within those big groupings for any kind of individual story or drama. I chose the gigundo-windows master shot I wanted, and left all the other frames in the dust.

Recently hitting a dead spot of several days’ duration, I decided to wander through The Ghosts Of Photo Attempts Past, and I saw a mix of bodies and light within the smallest 1/3 of a larger crowd shot that seemed worth re-framing, with a little softening effect to help the story along. Still not a masterpiece, but, since I was lucky enough to isolate it within a “Where’s Waldo” frame crammed with detail, it was something of a gift to salvage a chunk of it that I could actually care about.

Another orphan finds a home.

STOP AT “YES”

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE SEEMS TO BE A PROPENSITY, WITHIN THE DNA OF EVERY PHOTOGRAPHER, to “show it all”, to flood the frame with as much visual information as humanly possible in an attempt to faithfully render a story. Some of this may track back to the first days of the art, when the world was a vast, unexplored panorama, a wilderness to be mapped and recorded. Early shutterbugs risked their fortunes and their lives to document immense vistas, mountain ranges, raging cataracts, daunting cliffs. There was a continent to conquer, an immense openness to capture. The objectives were big, and the resultant pictures were epic in scale.

Seemingly, intimacy, the ability to select things, to zero in on small stories, came later. And for some of us, it never comes. Accordingly, the world is flooded with pictures that talk too loudly and too much, including, strangely, subjects shot at fairly close range. The urge is strong to gather, rather than edit, to include rather than to pare away. But there are times when you’re just trying to get the picture to “yes”, the point at which nothing else is required to get the image right, which is also the point at which, if something extra is added, the impact of the image is actually diminished. I, especially, have had to labor long and hard to just get to “yes”….and stop.

In the above image, there are only two elements that matter: the border of brightly lit paper lanterns at the edge of a Chinese New Year festival and the small pond that reflects back that light. If I were to exhaust myself trying to also extract more detail from the surrounding grounds or the fence, I would accomplish nothing further in the making of the picture. As a matter of fact, adding even one more piece of information can only lessen the force of the composition. I mention this because I can definitely recall occasions when I would whack away at the problem, perhaps with a longer exposure, to show everything in more or less equal illumination. And I would have been wrong.

Even with this picture, I had to make myself accept that a picture I like this much required so little sweat. Less can actually be more, but we have to learn to get out of our own way….to stop at “yes”.

ONE OUT OF FOUR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF YOU ARE DEPENDENT ON NATURAL LIGHT FOR YOUR ONLY SOURCE OF ILLUMINATION IN AN IMAGE, you have to take what nature and luck afford you. Making a photograph with what’s available requires flexibility, patience, and, let’s face it, a sizable amount of luck. It means waiting for your moment, hell, maybe your instant of opportunity, and it also means being able to decide quickly that now is the time (perhaps the only time) to press the button.

I recently had such a situation, measured in the space of several seconds in which the light was ready and adequate for a shot. And, as usual, the subject seemed as if it would serve up anything but acceptable conditions. The main bar of the classic western “joint” named Greasewood Flats, just outside of northern Scottsdale, Arizona, is anything but ideal in its supply of available light. Most of the room is a tomb, where customers become blobby silhouettes and fixtures and features are largely cloaked in shadow. I had squeezed off a few shots of customers queued up for bar orders, and they all registered as shifting shadows. The shots were unworkable, and I turned my attention to the fake-cowboy-ersatz-dude-ranch flavor of the grounds outside the bar, figuring that the hunt inside would be fruitless.

Minutes later, I was sent back inside the building to fetch a napkin, and found the bar empty of customers. I’m talking no human presence whatever. In an instant, I realized that the outside window light, which was inadequate to fill a four-sided, three-dimensional space, was perfectly adequate as it spread along just one wall. With crowds out of the way, the rustic detail that made the place charming was suddenly a big still-life, and the whole of that single wall was suddenly a picture. My earlier shots were too constrasty at f/5.6, so I tried f/3.5 and picked up just enough detail to fill the frame with Old West flavor. Click.

All natural light is a gift, but it does what it wants to do, and, to harness it for a successful shot, you need to talk nice, wait your turn, and remember to give thanks. And, in a dark room, be happy with one wall out of four that wants to work with you.

THE “EITHER/ORs”

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CAMERAS CAN EITHER TAKE CHOICE AWAY OR CHALLENGE YOU TO MASTER IT. If you’re a regular reader of this comic strip, you know all too well that I advocate making images with all manual settings rather than relying on automodes that can only come in a distant second to the human process of decision-making. People take better pictures with a camera than a camera can take alone. Can I get an Amen?

There is, of course, one choice you don’t get to make for any picture you create. You can’t mark a box called “the choice I made guarantees that everything in the image will work out.” Worse, there is always more than one choice being made in the creation of a photograph, and, even if you’re well-practiced and fast, you can’t make all of them perfectly. Choose one option and you are “un-choosing” another. The sum of the effect of all your choices together is what determines the final picture. That’s real work, and it certainly accounts for many people’s preference for automodes, since they obviate all those tough calls.

Nothing will force you to choose lots of options in short order like taking pictures of children at play. The image posted here, taken at a kindergarten playdate, shows a number of fast decisions that may or may not add up to an appealing picture, as lots of things are going on all at once. In the room where this was shot, space was tight, action was swift, white balances were wildly different in various zones within the room, and posing the kids in any way was absolutely impossible, due to their tender age and the fact that I wanted to be as invisible as possible, the better to catch their natural flow. To get pictures under this particular set of conditions, I had to decide how best to frame children who were grouping and ungrouping rapidly, where to get a fairly accurate register of color, customize my shutter speed and ISO with nearly every shot, and, as you see here, make my peace with whether the action implied in the shot outweighed the need for super sharpness.

You simply get into situations with some shots where you are not going to get everything you’d like to have, and you make decisions in the moment based on what each individual image seems to be “about”. Here I went for the joy, the bonding, the surging energy of the girls and let everything else take a back seat. Faced with the same situation seconds later, I might have remixed the elements to create a completely different result, but that is both the thrill and the bane of manual shooting. Automodes guarantee that you will get some kind of image, a very safe, if average, picture that allows you to worry less and possibly enjoy being in the moment to a greater degree….but you are the only factor than can take the photo to another level, to, in fact, take full responsibility for the result. It’s like the difference between taking a picture of Niagara Falls from your hotel room and taking it from a tightrope stretched across the raging waters.

And, ah, that difference is everything.

THE RELENTLESS MELT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE PEOPLE YOU PHOTOGRAPH BECAUSE THEY ARE IMPORTANT. Others are chosen because they are elements in a composition. Or because they are interesting. Or horrific. Or dear in some way. Sometimes, however, you just have to photograph people because you like them, and what they represent about the human condition.

That was my simple, solid reaction upon seeing these two gentlemen engaged in conversation at a party. I like them. Their humanity reinforces and redeems mine.

This image is merely one of dozens I cranked out as I wandered through the guests at a recent reception for two of my very dearest friends. Given the distances many of us in the room traveled to be there, it’s unlikely I will ever see most of these people again, nor will I have the honor of knowing them in any other context except the convivial evening that herded us together for a time. Because I was largely eavesdropping on conversations between small groups of people who have known each other for a considerable time, I enjoyed the privilege often denied a photographer, the luxury of being invisible. No one was asked to pose or smile. No attempt was made to “mark the occasion” or make a record of any kind. And it proved to me, once more, that the best thing to relax a portrait subject is……another portrait subject.

I assume from the body language of these two men that they are friends, that is, that they weren’t just introduced on the spot by the hostess. There is history here. Shared somethings. I don’t need to know what specific links they have, or had. I just need to see the echoes of them on their faces. I had to frame and shoot them quickly, mostly to evade discovery, so in squeezing off several fast exposures I sacrificed a little softness, partly due to me, partly due to the animated nature of their conversation. It doesn’t bother me, nor does the little bit of noise suffered by shooting in a dim room at ISO 1000. I might have made a more technically perfect image if I’d had total control. Instead, I had a story in front of me and I wanted to possess it, so….

Susan Sontag, the social essayist whose final life partner was the photographer Annie Liebovitz, spoke wonderfully about the special theft, or what she called the “soft murder” of the photographic portrait when she noted that “to take a photograph is to participate in another person’s mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.”

Melt though it might, time also leaves a mark.

Caught in a box.

Treasured in the heart.

Related articles

- Susan Sontag Musings Where You Least Expect Them (hintmag.com)

THE ANGEL’S IN THE DETAILS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I IMAGINE THAT, IF SOMEONE UN-INVENTED CHRISTMAS, the entire history of personal photography might be compressed into about twenty minutes. I mean, be honest, was there ever a single event or phase of human experience for which more images were clicked than the holiday season? Just given the sheer number of cameras that were found under the tree and given their first test drive right then and there, you’d have one of the greatest troves of personal, and therefore irreplaceable, images in modern history.

I IMAGINE THAT, IF SOMEONE UN-INVENTED CHRISTMAS, the entire history of personal photography might be compressed into about twenty minutes. I mean, be honest, was there ever a single event or phase of human experience for which more images were clicked than the holiday season? Just given the sheer number of cameras that were found under the tree and given their first test drive right then and there, you’d have one of the greatest troves of personal, and therefore irreplaceable, images in modern history.

Holidays are driven by very specific cues, emotional and historical.

We always get this kind of tree and we always put it in this corner of the room. I always look for the ornament that is special to me, and I always hang it right here. Oh, this is my favorite song. What do you mean, we’re not having hot chocolate? We can’t open presents until tomorrow morning. We just don’t, that’s all.

It’s tradition.

If, during the rest of our year, “the devil’s in the details”, that is, that any little thing can make  life go wrong, then, during the holidays, the angel’s in the details, since nearly everything conspires to make existence not only bearable, but something to be longed for, mulled over, treasured in age. Photographs seem like the most natural of angelic details, since they lend a gauzy permanence to memory, freezing the surprised gasp, the tearful reunion, the shared giggle.

life go wrong, then, during the holidays, the angel’s in the details, since nearly everything conspires to make existence not only bearable, but something to be longed for, mulled over, treasured in age. Photographs seem like the most natural of angelic details, since they lend a gauzy permanence to memory, freezing the surprised gasp, the tearful reunion, the shared giggle.

As the years roll on, little is recalled about who got what sweater or who stood longest in line at GreedMart trying to get the last Teddy Ruxpin in North America. Instead, there are those images…in boxes, in albums, on hard drives, on phones. Oh, look. He was so young. She looks so happy. That was the year Billy came home as a surprise. That was the last year we had Grandma with us. Look, look, look.

So remember, always….the greatest gifts you’ll ever receive aren’t under the tree.

Merry Click-mas.

ANOTHER YEAR OUT THE WINDOW

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF YOU WANT TO PUT A SMILE ON MY FACE WHEN I VISIT YOUR CITY, there is no sweeter sentence you can say to me than:

“I’ll drive”.

There is, for photographers, one way to maximize your time touring through other people’s towns, and that’s the time-honored tradition of “riding shotgun”. Drive me anywhere, but give me a window seat. I wasn’t trying to go for some kind of personal best in the area of urban side shots in 2013, but by good fortune I did snag a few surprises as I was ferried through various towns, along with a “reject” pile about a mile high. Like any other kind of shooting, the yield in window shooting is very low in terms of “killers per click”, but when you hit the target, you crack through a kind of “I’m new in town” barrier and take home a bit of the street for your own.

This guy just killed me (excuse the expression). He seemed like he was literally waiting for business to drop in (or drop dead), and meanwhile was taking in the view. Probably he didn’t even work for the casket company, in which case, what a bummer of neighbor to pick. Maybe he’s rent controlled.

This one took a little tweaking. The building was actually blue, as you see here, lit with subdued mood for the holidays. However, in lightening this very dark shot, the sky registered as a muddy brown, so I made a dupe, desaturated everything except the conservatory, then added tint back in to make the surrounding park area match the building. All rescued from an “all or nothing” shot.

I’m also ashamed to admit that I bagged a few through-the-window shots while actually driving the car, all done at red lights and so not recommended. Don’t do as I do, do as I……oh, you know.

Here’s to long shots, at horse tracks or in viewfinders, and the few that finish in the money.