THE WORKER’S SIGNATURE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE GERMAN PHOTOGRAPHER AUGUST SANDER (1876-1964) created one of the most amazing projects in the history of portraiture with his seminal book The Face of Our Time. Born into a world that defined people much more by class division and by the literal work of their hands, Sander created a document of a vanishing world in a very simple way, surrounding bricklayers, cooks, soldiers, and dozens of other professionals with the literal tools of their trades. His work influenced street photography and portraiture throughout the 20th century, acting as both document and commentary.

The manual trades that Sanders celebrated are rapidly vanishing as automation and changing tastes take away the tv repairmen, cobblers, and pillow makers of yesteryear, taking with them the physical look of their workplaces. It’s feels like I’ve happened upon an archaeological dig when I run across a place where handcrafted work takes place, and to photograph the shops where the old magic still happens. The encroachment into urban neighborhoods of chain stores and the crush of ever-higher rents are chasing out the last generations of tinkerers and makers. Storefronts and the stories that reside within them are winking out across the urban landscape.

August Sander’s challenge to present-day photographers is to bear witness to the worker’s signature, the mark he makes on the world and the echo he leaves behind when he departs. The world is always in the act of going partly instinct. The camera measures what we lose in the process. In Sander’s elegant, simple pictures of working people, there is a peaceful quality, as everyone seems fitted to their place and role in the world. As we photograph the final days of such a world, we are commenting on the uncertainty that follows it into our present age.

ASKING FOR YOUR VOTE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ANY CAMPAIGN YEAR COMES WITH ITS OWN QUOTIENT OF BAKED-IN CIRCUS FLAVOR. The way nations choose their leaders may be fair, unfair, inefficient, brilliant, or banal, but they never fail to offer up their own brand of home-grown crazy. There is no hat too undignified, no button too provocative, no face-paint too garish. Maybe camp-followers in an election are spiritual cousins of the fanboys who walk the halls of ComicCon, arrayed like Wonder Woman or Wolverine. Whatever the motivation, photographers paying any attention whatsoever in an election year can always find plenty of low-hanging fruit, anywhere voters gather.

The shot at left just had to be snapped, since it speaks to the kind of stuff that passes for entertainment on a day when the outside temperature at a Democratic rally in Arizona tops a balmy 108 and a campaign office built for several dozen volunteers attempts to host a horde of nearly 800. It makes cramming twenty clowns into a Volkswagen look like a card trick. And, apparently, on this particular day, the staff thought the best thing to facilitate the flow of foot traffic was to park a pair of life-size cutouts of JFK and President Obama right at the entrance, where people could slow down even further in search of a souvenir photograph, not by their next choice for Chief Executive, but a living president on his way out and a dead president more than half the crowd only knows through newsreel footage.

Not that anyone was going to get close enough to either Jack or Barry for a memorable snap, as the room was crammed tighter than the cab of the last elevator out of town, so, in the few seconds that I could stand in one place without being nudged inexorably toward the life-saving cartons of bottled water, I decided to pretend that the two prezzes were just as inconvenienced by the crush as the rest of us. Sadly, Jack’s head bent back a bit, revealing more glare than was truly presidential, but at least O seemed to be into the process. Hi, good to see ya….

Sometime politics is a proud procession, and sometimes it’s a clown parade. And yet, somehow, it’s always good for an occasional smile.

ALONE IN A CROWD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE CHOICE OF TIME, PLACE AND APPROACH IN THE MAKING OF A PORTRAIT is as individual as the human face itself. No two photographers have quite the same process for trying to capture the essence of personality with a camera. Moreover, having chosen a preferred path to making these most personal of images, we often are tempted to stray off of it. As with anything else in the art of creating photos, nothing, from formal studio settings to street candids, works all the time.

Just as one example, the key to portraits, for me, is to always be as fully mindful, in the moment, of the changes that a face can display within the space of a few seconds. You seem to be presented, from start to finish, with a different person altogether…..some other person that showed up, uninvited, to the shoot you’re doing for..someone else. Thus, it’s never a surprise to me when a subject views his/her image from a session, and immediately remarks, “that doesn’t even look like me”, which is, for them, quite correct. It’s as if their face showed something, just for a second, that they don’t recognize as their “official” face. And the photographer sees all these strangers blur by, like the shuffle of a deck of cards.

In photographing my wife Marian, I battle against her native resistance to having her face recorded, well, at all. It’s a rather invasive procedure for her, and, since the finest qualities of her face are revealed when she’s least self-conscious. That rules out studio settings, since all her “danger, Will Robinson” triggers will go off simultaneously the more formalized the situation becomes. I have to use that momentary mindfulness to sense when her face is ready….that is, when she is least aware of having her picture taken. That may mean that many other people are around her, since interaction is relaxing and distracting for her. In the above image, I got particularly lucky, since several factors converged in a moment that I could not have anticipated.

Listening to a history guide on the streets of Boston, Marian’s face set into a wonderful mix of serenity, focus, studiousness. Her finest qualities seem all to have coalesced in a single moment. Even better, although she is in a crowd, the arrangement of people surrounding her kept all other faces either out of focal register or partially hidden, rendering them less readable as full people. That gave the composition a center, as hers was the only complete face in view. Click and done.

Portraits are certainly about anticipation and preparation. But they also have to be about the reactivity of the photographer. And with something as mutative, and mysterious, as the human face, flexibility is a far more valuable tool than any lens or light in your kit bag.

EYE ON THE BALL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I CAN STILL HEAR MY LITTLE LEAGUE COACH’S VOICE, cured into a coarse hum by too many years of Lucky Strikes, hitting me in the back of my skull as I stood shakily in the batter’s box. If he had told me once, he had told me a thousand times: don’t try to hit every ball that comes across the plate. You swing like a rusty gate, he would tease me, or don’t eat their garbage. The main message, and one that I only intermittently received: wait for your pitch.

On those rare occasions when I didn’t fish wildly in the air for every single thing that sailed in from the mound, I took great encouragement from his voice saying, good eye. Strangely, I had earned praise for essentially doing nothing, but, hey, I’d take it.

Coach sometimes comes to mind when I view the results of some of my hastier photographic decisions.

There is, for photogs, a very real translation of “wait for your pitch”, and it’s more important in the digital era because it’s such an easy rule to adhere to. Simply, you must keep shooting long enough to get the frame you saw in your mind. There can be no, “I’ve already taken a lot of frames”, or “they’re waiting for me to finish up” or “maybe today’s not my day for this shot.” First of all, it’s your picture. If you want it, take it. Secondly, there is no such thing as “a lot of frames”. There is only enough frames. If clicking one more, hell, ten more, will get you your shot, then do it. There is no phantom film counter warning you that you only have four more Kodachrome exposures left.

I am preaching this particular commandment all too loudly today because I am kicking myself for not living up to it recently. In the top frame, I got every element of a quaint old Amtrak ticket window that appealed to me, including the patterned skylight, the bored agent, the square arrangement of the Deco-ish counter space, and the left and right details of an old archway and a marble wall. Everything except the intrusive passersby on the left. They are sadly out-of-sync with the time-feel of the rest of the shot, and, had I not felt that I had nailed the general exposure and feel of the image, I might have waited for them to move out of frame, and gotten everything I wanted.

But I didn’t. I settled for “close enough”, and moved on to the next subject. Later, in post-production, I could certainly crop my squatters out, but at the cost of the overall composition. I now had to make do with what was left. I managed to reframe for another square shot that included nearly all the same elements. But it was “nearly”, not “all”. And “all” is what I could have had if I hadn’t tried to swing at the wrong ball. You can’t make a good shot out of a bad shot, and when an opportunity is gone, there isn’t a piece of software in the world that can make a miracle out of what’s not in your camera.

Wait for your pitch.

THOSE WHO STAND AND WAIT

Please Listen For Announcements, 2015. The iconic waiting room at Los Angeles’ Union Station terminal.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SHOW ME A HOLIDAY SEASON AND I’LL SHOW YOU PEOPLE WAITING FOR SOMETHING TO HAPPEN. They form lines for special orders, last-minute items, a kid’s brief audience with Santa. They hope to bump someone on a flight, beat someone out of a bargain, talk someone into a discount, refund or exchange. But mostly, they wait.

For as many festive holiday subjects that dance before the photographer’s eye, there are many more scenarios in which nothing much happens but..the waiting. And, while this seemingly endless hanging-out never offers images that define joy or wonder, they are fodder to the street shooter within us, the guy looking for stories. Stories of tired feet. Tales of people who can’t get a connecting flight ’til tomorrow at the earliest. Sagas of mislaid plans and misbegotten presents. Folklore of folks who are lost, lonely, disappointed, and down. In short, all of us, at various times.

Transit points are often among the most poignant during the season, with legions of faces that plead, what’ll I get for her? How will I get all the way down this list? How soon can I get home? Your best bet? Hang at the train stations, the port authorities, the airports, and hear the plaintive strains of I’ll Be Home For Christmas sung in the key of ‘as if’. Seek out those aches, that weariness, the many false starts and stumbling finishes of the holidays. And keep your camera ready, hungry for whatever visions dance in your head.

INTERACTIONS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S FAIRLY EASY TO FIGURE OUT WHERE TO TAKE YOUR CAMERA if you are trying to visually depict a vibe of peace and quiet. Landscapes often project their serenity onto images with little translation loss, and you can extract that feeling from just about any mountain or pond. For the street photographer, however, mining the most in terms of human stories is more particularly about locations, and not all of them are created equal.

Street work provides the most fodder for storytelling images in places where dramatically concentrated interactions occur between people. One hundred years ago, it might have been the risk and ravage of Ellis Island. On any given sports Sunday, the opposing dreams that surround the local team’s home stadium might provide a rich locale. But whatever the site, social contention, or at least the possibility of it, generates a special energy that feeds the camera.

In New York City, the stretch of Fifth Avenue that faces the eastern side of the Empire State Building is one such rich petri dish, as the street-savvy natives and the greener-than-grass tourists collide in endless negotiation. Joe Visitor needs a postcard, a tee-shirt, a coffee mug, or a discounted pass to the ESB observation deck, and Joe Hometown is there to move the goods. Terms are hashed over. Information slithers in and out a dozen languages, commingling with the verbal jazz of Manhattan-speak. Deals are both struck and walked away from. And as a result, stories flow quickly past nearly every part of the street in regular tidal surges. You just pick a spot and the pictures literally come to you.

In these images, two very different tales unfold in nearly an identical part of the block. In the first, bike rickshaw drivers negotiate a tourist fare. How long, how far, how much? In the second, two regulars demonstrate that, in New York, there is always the waiting. For the light. For parking. For someone to clear away, clear out or show up. But always, the waiting. These are both little stories, but the street they occur on is a stage that is set, struck and re-set constantly as the day unfolds. A hundred one-act plays a day circle around those who want and those who can provide.

Manhattan is always a place of great comings and goings, and here, in front of the most iconic skyscraper on earth, those who haven’t seen anything do business with those who’ve seen it all. Street photography is about opportunity and location. Some days give you one or the other. Here, in the city that never sleeps, both are as plentiful as taxicabs.

SEE DICK THINK.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FORGET BLOWN EXPOSURES, SHAKY SNAPSHOTS, AND FLASH-SATURATED BLIZZARDS. The hardest thing to avoid in the taking of a picture is winding up with a picture full of other people taking a picture. Hey, democracy in art, power to the people, give every man a voice, yada yada. But how has it become so nearly impossible to keep other photographers from leaning in, crossing through, camping out or just plain clogging up every composition you attempt?

And is this really what I’m irritated about?

Maybe it’s that we can all take so many pictures without hesitation, or, in many cases, without forethought or planning, that the exercise seems to have lost some of its allure as a deliberate act of feeling/thinking/conceiving. Or as T.S. Elliot said, it’s not sad that we die, but that we die so dreamlessly. It’s enough to make you seek out things that, as a photographer, will actually force you to slow down, consider, contemplate.

And one solution may lie in the depiction of other people who are, in fact, taking their time, creating slowly, measuring out their enjoyment in spoonfuls rather than buckets. I was recently struck by this in a visit to the beautiful Brooklyn Botanical Gardens on a slow weekday muted by overcast. There were only a few dozen people in the entire place, but a significant number of those on hand were painters and sketch artists. Suddenly I had before me wonderful examples of a process which demanded that things go slowly, that required the gradual evolution of an idea. An anti-snapshot, if you will. And that in turn slowed me down, and helped me again make that transition from taking pictures to making them.

Picturing the act of thought, the deep, layered adding and subtracting of conceptual consequence, is one of the most rewarding things in street photography. Seeing someone hatch an idea, rather than smash it open like a monkey with a cocoanut does more than lower the blood pressure. It is a refresher course in how to restore your own gradual creativity.

A GAME OF INCHES

Carry-Out At Canter’s, 2015. One generous hunk of window light can be all you need, even on a cel phone.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WINDOW LIGHT IS A BOY PHOTOGRAPHER’S BEST FRIEND. The glass usually acts like a diffuser, softening and warming the rays as they enter, making for intimate portrait and street shots. Window light tends to wrap around the objects in its path, adding a look of depth and solidity to furniture and people. It’s also uncomplicated, universally available, and free. And that’s great for cell phone cameras.

At this writing, Apple’s next iPhone will soon up the ante on both resolution and light sensitivity, meaning that more and more shots will be saved that just a few years ago would have been lost, as the mobile wars give us more features, more control, and more decision-making options that recently belonged only to DSLRs and other upper-end product. That will mean that the cameras will perform better with less light than ever before, over-coming a key weakness of early mobiles.

That weakness centered on how the camera would deal with low-light situations, which was to open to its widest aperture and jack up the ISO, often resulting is grungy, smudgy images. Turn too many inches away from prime light (say a generous window in daytime) and, yes, you would get a picture, but, boy, was it ever dirty, the noise destroying the subtle gradation of tones from light to dark and often compromising sharpness. Those days are about to end, and when they do, people will have to seriously ask if they even need to lug traditional imaging gear with them, when Little Big Boy in their back pocket is bringing the “A” game with greater consistency.

As this new age dawns, experiment with single-point window light to see how clean an image it will deliver on a cel phone. Pivot away from the light by a few inches or feet, and compare the quality of the images as you veer deeper into shadow. You will soon know just how far you can push your particular device before the noise starts creeping in, and having that limit in your head will help you assess a scenario and shoot faster, with better results. Camera phones, at least at their present state of development, will only do so much, but you may be surprised at just how high their top end actually is. You need not miss a great shot just because you left your Leica in your other pants. As usual, the answer is, Always Be Shooting.

OH, SNAP

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MOST OF US ENTER PHOTOGRAPHY WITH THE SAME AIM, that is, to arrest the flight of something precious with the trick effect of having frozen time. Someone or something is passing through our life all too quickly, and we use our cameras to isolate small pieces of those passages like a butterfly inside an amber cube. That means that our first work is our most personal, and, while we may later graduate to more general, more abstract recordings of light, subject, and shape, we all begin by chronicling events of the most intimate nature.

And as we grow into more interpretative, less reportorial imaging, we also grow away from the clear, focused aim of that earlier work. Be it a triptych of a birthday, an anniversary, a wake or a christening, we understand clearly what a snap is for, what it was after. Its purpose and its message are unmistakable, something that cannot always be said for other kinds of photographs. Indeed, looking back on some of our own output at the distance of just a few years, we can actually be at a loss to explain what we were going after in a given photograph, what we were trying to say. This doesn’t happen with the snap. Its subject matter, and the degree to which we correctly captured it, is readily visible.

This may speak to why photographers are often asked why they don’t take “more pictures of people”, or, more specifically, why did you take a picture of this person? Do you know him? No? Then why……..?? It isn’t that a connection between yourself and people who are strangers to you can’t be made in a photograph. It’s that it’s a lot harder to effectively tell that story. it requires less from the camera and more from you.

You need to fill in a lot more blanks in a tale in which fewer elements are pre-provided. You can convey something universal about the human condition with a picture of something outside your own experience, certainly. It’s just that it’s easier to make the link that exists between you, your mother, her birthday, and her surrounding gang of friends than between yourself and someone who is essentially alien to you, or to the rest of us. Of course, on the other side of the ledger, you can also shoot a bajillion pictures of those closest to you, and still manage to convey nothing of their true selves. Mere technical acuity is not intimacy, or vision.

Still, in general terms, the snap deserves a lot more respect than it gets, simply because there is, in these personal images, a near-perfect match alignment of shooter, subject and clarity of purpose. By contrast, when we venture out into the greater world, trying to tell equally effective stories with much less information is hard. Not impossible, but, man, really hard.

TAKE ME OUT TO THE “ALL” GAME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU SEE RIDICULOUS ARTICLES FROM TIME TO TIME claiming that baseball has been replaced as America’s Pastime. Such spurious scribblings invariably point to game attendance, TV ratings, or some other series of metrics that prove that football, basketball, and, who knows, strip Scrabble have reduced baseball to some quaint state of irrelevancy. All such notions are mental birdpoop for one salient reason. No one is giving due attention to the word pastime.

Not “passion”. Not “madness”. Not even “loyalty”. Pastime. A way of letting the day go by at a leisurely pace. A way to gradually unfurl afternoons like comfy quilts. People-watching. Memory. Sentiment. Baseball is for watchers, not viewers, something that television consistently fails to realize. It’s the stuff that happens in the pauses, of which the game has plenty. Enjoying baseball, and photographing it as an experience, is about what happens in the cracks.

Images are waiting to be harvested in the dead spots between pitching changes. The wayward treks of the beer guys. The soft silence of anticipatory space just before the crack of a well-connected pitch. TV insists on jamming every second of screen time-baseball with replays, stat tsunamis, and analysis. Meanwhile, “live”, in the stadium, the game itself is only part of the entertainment. Sometimes, it actually drops back to a distant second.

Only a small percentage of my baseball pictures are action shots from the field: most are sideways glances at the people who bring their delight, their dreams, and their drama to the game. For me, that’s where the premium stories are. your mileage may vary. Sometimes it’s what’s about to happen that’s exciting. Sometimes it’s the games you remember while watching this one. There are a lot of human factors in the game, and only some of them happen between the guys in uniform.

Photography, as a pastime, affords a great opportunity to show a pastime. America’s first, best pastime.

It’s not just a ballgame. It’s an “all” game.

Root, root, root.

EAVES-EDITING

by MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE SIDE BENEFITS OF PHOTOGRAPHY is that you don’t always have to pick your own subject. Sometimes someone else’s idea of a potentially good image can be yours as well. You simply camp yourself right next to where they’re working and pick off your own shots of their project. Assuming that everyone’s polite and there are no issues of neighborly nibbing, it can work. Just ask anyone who’s clicked away at a presidential press conference or the sudden exit of a celebrity through a side entrance.

Of course, when literally dozens of cameras are trained on a single event, its likely that everyone will come away with the same photos, or very nearly. The moment the prime minister points to drive home his main point, click. The instant when the judges place the tiara on the winning Miss Tomato Paste candidate, click. Sometimes, however, you can kind of “eaves-edit” on just one other shooter’s set-up and edit the shots a different way than he does. You’re not running the session, but you could come away with a better result than he does, based on your choices.

I recently came upon a man shooting a girl in the streets of a kind of faux-village retail environment in Sedona, Arizona. Obviously, the main feature was the lady’s infectious and natural smile. As I came quietly upon them, however, Mr. Cameraman was having a problem keeping that smile from exploding into a full-blown laughing fit. Ms. Subject, in short, had the mad giggles.

Now, from that point onward, I have no idea of what he went home with in the way of a final result, as I had decided that the crack-ups would make better pictures than a merely sweet set of candids. It just seemed more human to me, so I only shot the moments in which she couldn’t compose herself, and took off from there.

I didn’t want to overstay my welcome, so I snapped my little chunk of Mr. Cameraman’s moment and sneaked off, like fast. As I slinked away, I could still hear Ms. Subject telling him, through fits of laughter, “I am so sorry.” She may have been, but I wasn’t.

YOU’RE GREAT, NOW MOVE, WILLYA?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF MY FAVORITE SONGS FROM THE ’40’s, especially when it emanates from the ruby lips of a smoking blonde in a Jessica Rabbit-type evening gown, conveys its entire message in its title: Told Ya I Love Ya, Now Get Out! The hilarious lyrics speak of a woman who acknowledges that, yeah, you’re an okay guy, but don’t get needy. No strings on me, baby. I’ll call you when I want you, doll. Until then, be a pal and take a powder.

I sometimes think of that song when looking for street images. Yes, I’m aware that the entire sweep of human drama is out there, just ripe for the picking. The highs. The lows. Thrill of victory and agony of de feet. But. I always feel as if I’m cheating the world out of all that emotional sturm und drang if I want to make images without, you know, all them people. It’s not that I’m anti-social. It’s just that compelling stuff is happening out there that occasionally only gets compromised or cluttered with humans in the frame.

Scott Kelby, the world’s biggest-selling author of photographic tutorials, spends about a dozen pages in his recent book Photo Recipes showing how to optimize travel photos by either composing around visitors or just waiting until they go away. I don’t know Scott, but his author pic always looks sunny and welcoming, as if he really loves his fellow man. And if he feels it’s cool to occasionally go far from the madding crowd, who am I to argue? There are also dozens of web how-to’s on how to, well, clean up the streets in your favorite neighborhood. All of these people are also, I am sure, decent and loving individuals.

There is some rationality to all this, apart from my basic Scrooginess. Photographically, some absolutes of abstraction or pure design just achieve their objective without using people as props. Another thing to consider is that people establish the scale of things. If you don’t want that scale, or if showing it limits the power of the image, then why have a guy strolling past the main point of interest just to make the picture “human” or, God help us, “approachable”?

Faces can create amazing stories, imparting the marvelous process of being human to complete scenes in unforgettable ways. And, sometimes, a guy walking through your shot is just a guy walking through your shot. Appreciate him. Accommodate him. And always greet him warmly:

Told ya I love ya. Now get out.

ACCUMULATIONS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

STREET PHOTOGRAPHY CONSISTS MOSTLY OF SHOWING PEOPLE in the full context of their regular worlds.

In terms of portraits or candids, it’s usually sufficient to showcase those we know in controlled environments….family gatherings, special occasions, a studio setting. However, to reveal anything about the millions of strangers we encounter over a lifetime, we only have context to show who they are and what they do. To say something about these fascinating unknowns, we truly need the “props” that define their lives.

I never thought it was that profound to just snap a candid of someone walking down the street. Walking to where? To do what? To meet whom? Granted, a person composed as part of an overall street scene can be a great compositional elements all by him/herself, but to answer the question, who is this person? requires a setting that fixes him in time, in a role or a task. Thus pictures of people doing something, i.e., being in their private universe of tools, objects, and habits…now that can make for an interesting study.

We now have successful reality TV shows like Somebody’s Gotta Do It which focus on just what it’s like to perform other people’s jobs, the jobs we seldom contemplate or tend to take for granted. It satisfies a human curiosity we all share about what else, besides ourselves, is out there. Often we try to gain the answer by sending probes to the other side of the galaxy, but, really, there’s plenty to explore just blocks from wherever we live. Thing is, the people we show make sense only in terms of the accumulations of their lives…the objects and equipment that fill up their hour and frame them in our compositions.

The legendary Lewis Hine made the ironwalkers of Manhattan immortal, depicting them in the work of creating the city’s great skyscrapers. Others froze workers and craftsmen of every kind in the performance of their daily routines. Portraits are often more than faces, and showing people in context is the real soul of street photography.

TESTIMONY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY WAS IN ITS INFANCY WHEN IT WAS FIRST PRESSED INTO SERVICE as a reportorial tool, a way of bearing witness to wars, disasters, and the passing parade of human folly and fashion. Since that time, at least a part of its role has been as a means of editorial commentary, a light shone on crisis, crime, or social ills. The great urban reformer Jacob Riis used it to chronicle the horrific gulf between poor and rich in the legendary photo essay How The Other Half Lives. Arthur Rothstein, Dorothea Lange and Lewis Hine, among many others, turned their cameras on the desperate need and changing landscape of America’s Great Depression. And now is the time for another great awakening in photography. It’s time to show where our cities need to go next.

Politics aside, the rotting state of our urban infrastructures is an emergency crying out for the visual testimony that photographers brought so eloquently to bear on poverty and war in ages past. The magnifying glass needs to be turned on the neglect that is rapidly turning America’s urban glory into rust and ruin. And no one can tell this story better than the camera.

We can fine-tune all the arguments about how to act, what to fund, and how to proceed. That’s all open to interpretation and policy. But the camera reveals the truths that are beyond abstraction and opinion. The underpinnings of one of the world’s great nations are rapidly dissolving into exposed rebar and pie-crust pavement. If part of photography’s mission is to report the news, then the decline of our infrastructure is one of the most neglected stories in the world’s visual portfolio. Photographers can entice the mind into action, and have done so for nearly two centuries. They have peeled back the protective cover of politeness to reveal mankind at its worst, and things have changed because of it. Agencies have been formed. Action has been accelerated. Lives have been changed. Jobs have been created.

It didn’t used to be an “extra credit” question on the exam of life just to maintain what amazing things we have. Photographers are citizens, and citizens move the world. Not political parties. Not kings or emperors. History is created from the ground up, and the camera is one of the most potent storytelling tools used in shaping that history. The story of why our world is being allowed to disintegrate is one well worth telling. Capturing it in our boxes just might be a way to shake up the conversation.

Again.

A KISS ON VETERAN’S DAY

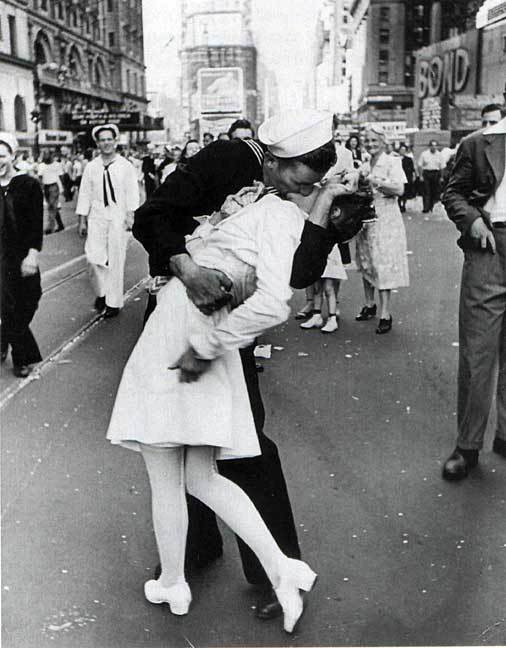

A PICTURE, WHEN IT TRULY COMMUNICATES, isn’t worth a thousand words. The comforting cliché notwithstanding, a great picture goes beyond words, making its emotional and intellectual connection at a speed that no poet can compete with. The world’s most enduring images carry messages on a visceral network that operates outside the spoken or written word. It’s not better, but it most assuredly is unique.

Most Veteran’s Days are occasions of solemnity, and no amount of reverence or respect can begin to counterbalance the astonishing sacrifice that fewer and fewer of us make for more and more of us. As Lincoln said at Gettysburg, there’s a limit to what our words, even our most loving, well-intended words, can do to consecrate that sacrifice further.

But images can help, and have acted as a kind of mental shorthand since the first shutter click. And along with sad remembrance should come pictures of joy, of victory, of survival.

Of a sailor and a nurse.

Alfred Eisenstaedt, the legendary photojournalist best known for his decades at Life magazine, did, on V-J day in Times Square in 1945, what millions of scribes, wits both sharp and dull, couldn’t do. He produced a single photograph which captured the complete impact of an experience shared by millions, distilled down to one kiss. The subjects were strangers to him, and to this day, their faces largely remain a mystery to the world. “Eisie”, as his friends called him, recalled the moment:

In Times Square on V.J. Day I saw a sailor running along the street grabbing any and every girl in sight. Whether she was a grandmother, stout, thin, old, it didn’t make a difference. I was running ahead of him with my Leica, looking back over my shoulder, but none of the pictures that were possible pleased me. Then suddenly, in a flash, I saw something white being grabbed. I turned around and clicked the moment the sailor kissed the nurse. If she had been dressed in a dark dress I would never have taken the picture. If the sailor had worn a white uniform, the same. I took exactly four pictures. It was done within a few seconds.

Those few seconds have been frozen in time as one of the world’s most treasured memories, the streamlined depiction of all the pent-up emotions of war: all the longing, all the sacrifice, all the relief, all the giddy delight in just being young and alive. A happiness in having come through the storm. Eisie’s photo is more than just an instant of lucky reporting: it’s a toast, to life itself. That’s what all the fighting was about anyway, really. That’s what all of those men and women in uniform gave us, and still give us. And, for photographers the world over, it is also an enduring reminder from a master:

“This, boys and girls, is how it’s done.”

CAUSE AND EFFECT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE’S NOTHING WORSE THAN COMING HOME FROM A SHOOT realizing that you only went halfway on things. Maybe there was another way to light her face. Did I take a wide enough bracket of exposures on that sunset? Maybe I should have framed the doorway two different ways, with and without the shadow.

And so on. Frequently, after cranking off a few lucky frames, we’re like kids walking home from confession, feeling fine and pure at first, and then remembering, “D’OH! I forgot to tell Father about the time I sassed my teacher!”

Too Catholic? (And downright boring on the sins, by the way..but, hey) Point is, there is always one more way to visualize nearly everything you care enough about to make a picture of. For one thing, we are always shooting either the cause or the effect of things. The great facial reaction and the surprise that induces it. The deep pool of rain and the portentous sky that sent it. The force that’s released in an explosion and the origin of that force. When we’re there, when the magic of whatever we came to see is happening, right here, right now, we need to think up, down, sideways for pictures of all of it, or as many as we can capture within our power….’cause once you’re home, safe and dry, it’s all different. The story perishes like a soap bubble. Shoot while you’re there. Shoot for all the story is worth.

It can be simple things. I saw the above image at one of the lesser outbuildings at Taliesin West, Frank Lloyd Wright’s legendary teaching compound in Scottsdale, Arizona. An abstract pattern made from over-hanging strips of canvas,used as makeshift shade on a path. But when I reversed my angle and shot the sidewalk instead of the sky, I saw the effect of that cause, and it appealed to me too (see left). One composition favored color, while the other seemed to dictate black & white, but they both could serve my purpose in different ways. Click and click.

It bears remembering that the only picture that is guaranteed to be a failure is the one you didn’t take. Flip things around. Re-imagine the order, the role of things. Go for one more version of what’s “important”.

Hey, you’re there anyway.…..

WHAT SIZE STORY?

iPhone 6 debut at Apple Store in Scottsdale, Arizona, September 19, 2014. Sometimes the story is “the crowd…”

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN THE EARLY 1950’s, AS TELEVISION FIRST BLINKED INTO LIFE ACROSS AMERICA, storytelling in film began to divide into two very clearly defined camps. In theatres, desperate to retain some of the rats who were deserting their sinking ships to bathe in cathode rays at home, movie studios went for stories that were too big to be contained by the little screen, and almost too big for theatres. You remember the wider-than-thou days of Cinemascope, VistaVision, Todd-Ao, Cinerama and Super-Panavision, as well as the red-green cardboard glasses of 3-D’s first big surge, and the eye-poking wonders of House Of Wax, Creature From The Black Lagoon and Bwana Devil. Theatres were Smell-O-Vision, True Stereophonic Reproduction and bright choruses of Let’s Go Out To The Lobby sung by dancing hot dogs and gaily tripping soda cups. Theatres was Big.

The other stories, the TV stories, were small, intimate, personal, compact enough to cram into our 9-inch Philcos. Tight two-shots of actors’ heads and cardboard sets in live studios. It was Playhouse 90 and Sylvania Theatre and The Hallmark Hall Of Fame. Minus the 3,000 Roman extras and chariot races, we got Marty, Requiem For A Heavyweight, and On The Waterfront. Little stories of “nobodies” with big impact. Life, zoomed in.

For photographers, pro or no, many stories can be told either in wide-angle or tight shot. Overall effect or personal impact. You can write your own book on whether the entire building ablaze is more compelling than the little girl on the sidewalk hoping her dog got out all right. Immense loads of dead trees have been expended to explore, in print, where the framing should happen in a story to produce shock, awe or a quick smile. I like to shoot everything every way I can think of, especially if the event readily presents more than one angle to me.

The release of the new iPhone 6, which dropped worldwide today, is a big story, of course, but it consists of a lot of little ones strung together. Walk the line of the faithful waiting to show their golden Wonka ticket to gain admission to the Church of Steve and you see a cross-section of humankind represented in the ranks. Big things do that to us; rallies, riots, parties, flashmobs, funerals….the big story happens once a lot of little stories cluster in to comprise it.

Simply pick the story you like.

Remember, just like the phone, they come in two sizes.

GIVE IT YOUR WORST SHOT

Are you going to say that Robert Capa’s picture of the D-day invasion would speak any more eloquently if it were razor-sharp? I didn’t think so.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE EARLY YEARNING OF PHOTOGRAPHERS TO MASTER OR EXCEED THE TECHNICAL LIMITS OF THEIR MEDIUM led, in the 1800’s, to a search for visual “perfection”. For rendering tones accurately. For capturing details faithfully. And, above all, for tight, sharp focus. This all made perfect sense in an era when films were so slow that people sitting for portraits had to have steel rods running up the backs of their necks to help them endure three-minute exposures. Now, mere mechanical perfection long since having become possible in photography, it’s time to think of what works in a picture first, and what grade we get on our technical “report card” second.

This means that we need no longer reject a shot on technical grounds alone, so long as it succeeds on some other platform, especially an emotional one. Further, we have to review and even re-review images, by ourselves as well as others, that we think “failed” in one way or another, and ask ourself for a new definition of what “failure” means. Did the less-than-tack-sharp focus interfere with the overall story? Did the underexposed sections of the frame detract from the messaging of what was more conventionally lit? Look to the left. at Robert Capa’s iconic image of the D-Day invasion at Normandy. He was just a little busy dodging German snipers to fuss with pinpoint focusing, but I believe that the world jury has pretty much ruled on the value of this “failed” photo. So look inward at the process you use to evaluate your own work. Give it your worst shot, if you will, and see what you think now, today.

The above image came from a largely frustrating day a few years back at a horse show in which I spent all my effort trying to freeze the action of the riders, assuming that doing so would deliver some kind of kinetic drama. I may have been right to think along these lines, but doing so made me automatically reject a few shots that, in retrospect, I no longer think of as total failures. The equestrienne in this frame looks as eager, even as exhausted as her mount, and the slight blur in both of them that I originally rejected now seems to work for me. There is a greater blur of the surrounding arena, which is fine, since it’s merely a contextual setting for the foreground figures, but I now have to wonder if I would like the picture better (given that it’s supposed to be suggestive of speed) if the foreground were completely sharp. I’m no longer so sure.

I think that all images have to stand or fall on what they accomplish, regardless of discipline or intention.We only kid ourselves into equating technical perfection with aesthetic success. Sometimes they walk into the room hand in hand. Other times they arrive in separate cars.

EAT ALL YOU TAKE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF YOU’VE EVER RELIED ON UNCLE SAM FOR YOUR THREE SQUARES A DAY (thanks for your service), you know that, at least in the military, waste is worse than gluttony. Got a man-sized appetite? Great. Go back for seconds. Or thirds. But the taxpayers paid for that creamed chipped beef on toast, so if you put it on your plate, you’d better also put it down your gullet. Take All You Want, but Eat All You Take.

Same with composing a street photo. God knows that often you’re up to your armpits in sensory overload. Bright lights, big city, busy intersections, a visual smorgasbord (don’t write posts when you’re hungry!) of input. Sure, you can stick it all in your image, but, in the same way that a shavetail recruit shoves mashed potatoes and ham and ice cream sky-high on his tray….you’d better eat it all. Just showing a chaotic jumble of elements is not “reportage”, nor is it particularly inspiring. You’re on the street to tell a story. If your story is merely “gee, it’s really crowded here today”, you probably need to hone your narrative skills, and it might be smart to start carving stuff out of the composition to, let us say, let it breathe a little.

Shoot all you want. Use all you shoot.

Hollywood Boulevard is a place where absurd levels of street theatre are as normal as fire hydrants and stop lights. It’s in a perpetual state of over-the-top, so much so that it’s damned near impossible, amidst the mimes, acrobats, dancers and show biz mutants, for anyone to draw more than a distracted nanosecond of attention to themselves. Taking photos of this non-stop ballet of weird between jaded tourists and frantic performers can easily become the visual equivalent of the buck private’s overloaded dinner tray. A mess, with all the gravies, juices and seasonings of the city running together.

Or you could try the dead opposite. One Sunday afternoon near sunset, I was lucky enough to see this wondrous fellow, creating his own mix of lucha libre and hip-hop in front of his own sad little stereo, working in isolation just across the street from the most heavily trafficked sites in that part of Hollywood. After shooting a few frames that showed him from several angles, I decided that his performance was story enough, all by itself. I didn’t need to show the thrilled reaction of passersby, or frame the shot to include popular destinations like the Chinese theatre or the teeming souvenir shops that scream so loudly up and down the block. Simply, including all that other glitter and glitz would have robbed our friend of his moment in the sun. I just liked him better as king of the block.

Full disclosure: had I not committed a lifetime of over-crowding flubs in my own images, I probably wouldn’t have felt compelled to write this post at all. But part of this enterprise is taking my lumps when I go off the rails, and doing penance is the first step to healing, blah blah blah…

Which is all to say, some photos need side dishes. Sometimes, however, you just want the meat and potatoes.

Again, never write when you’re hungry.

THE PICK-UP GAME

Oasis (2016)

By MICHAEL PERKINS

STREET PHOTOGRAPHY, FOR ME, INVOLVES AN OCCASIONAL BOUT OF LONGING, in that I am frequently on hand to record lives that, at least in part, I’d like to visit for longer than the length of a shutter snap. Not all street scenes are inviting, of course. Often we chronicle things that we are profoundly grateful are not part of our own lives. Other times, we accidentally preserve something that is so shrouded in mystery that the resulting images provide endless wellsprings of speculation…just what was it that we thought we saw, both at the moment of taking, and later? And then there’s what the taking of these images says about us personally. Some of our eavesdropping makes us feel privileged. Some makes us feel stained by the ugliness of our invasions.

And then there are the blessed accidents, the pictures we didn’t set out to take at all, such as the photo you see here. I was actually not in active shooting mode when I passed this pickup game of handball in a neighborhood in Queens over the past summer. To tell the truth, since I was trying to find an address at the time, I might very likely have passed these players completely by, had one of their tosses not jumped the fence of their tiny parcel of blacktop and literally rolled to my feet.

The ball re-directed my attention, as did several clear, high calls of “hey mister!” and “sir, would you mind..?” Pitching it back, I saw the boys’ playspace as the tiny oasis it was, crammed in on all sides by the neighborhood’s skyward crush. Next, I noticed the wonderful warmth of the mid-morning sun, and took a few seconds to allow the combatants to resume play, and, more importantly, forget about the Nice Old Guy Who Gave Them Back Their Ball. I took only two frames, fearful that one of the players would remember having seen the Nikon around my neck. Fortunately, the game was a much better claim on their attention, and I liked one of the tries I had made.

Street work is, more often than not, a matter of being there when someone else’s life happens. Seldom does that life reach out and ask to be noticed, to make a request on your time. In such moments, all of life becomes, for an instant, a universal pick-up game, something in which we’ve actually been invited to participate.

Share this:

December 25, 2016 | Categories: Americana, Cities, New York, Street Photography | Tags: documentary photography, social commentary | Leave a comment