FACING UP

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE LUXURY THAT PAINTERS HISTORICALLY ENJOYED OVER PHOTOGRAPHERS was the pure prolonged incubation time between their conception of a thing and its realization on the canvas. Whatever else painting is, it is never an instantaneous process, something that is especially true for portraits. The daubing of strokes, mixing of paint, the waiting for the light, and the waiting for the model to arrive (take a bathroom break, eat dinner, etc.) all contribute to painting’s bias toward the long game. The process cannot be hurried. There is no pigmentary equivalent of the photographic snap shot. Patience is a virtue.

The first photographs of people were likewise a gradual thing, with extended exposure times dictated by the slow speed of early plate and film processes. Once that obstacle was overcome, however, it became a simple thing to snap a person’s face in less and less time. Today, outside of the formal studio experience, most of us freeze faces in record timae, and that may be a bit of a problem in trying to create a true portrait of a person.

Portraits are more than mere recordings, since the subject matter is infinitely more complex than an apple or a vase of flowers. The daunting task of trying to capture some essential quality, some inner soulfulness with a mechanical device should make us all stop and think a little, certainly a little longer than a fraction of a second. Portraits at their best are a kind of psychoanalysis, an negotiation, maybe even a co-creation between two individuals. The best portraitists can be said to have produced a visible relic of something invisible. Can that be done in the instant that it takes to shout “cheese” at somebody?

And if the process of portraiture is, as I argue, an innately personal thing, how can we trust the “street portraits” that we steal from the unsuspecting passerby? Are any of these images revelatory of anything real, or have we only snatched a moment from the onrushing current of a person’s life? Taking the argument away from the human face for a moment, if I take a picture of a single calendar date page, have I made a commentary on the passage of time, or merely snapped a piece of paper with a number on it?

Painters have always been forced into some kind of relationship with their subjects. Some fail and some succeed, but all are approached with an element of planning, of intent. By contrast, the photographer must apprehend what he wants from a face in remarkably short time, and hope his instinct can make an intimate out of a virtual stranger.

THE GENESIS OF REAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

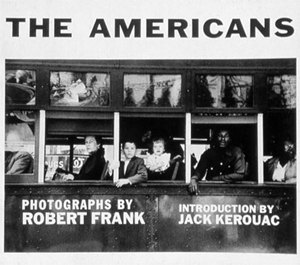

“(the book is) flawed by meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposure, drunken horizons, and general sloppiness, (showing) a contempt for quality and technique…” –Popular Photography, in its 1958 review of The Americans

THOSE WORDS OF DISDAIN, designed to consign its subject to the ash heap of history, are now forever attached to the photographic work that, instead of vanishing in disgrace, almost single-handedly re-invented the way the world saw itself through the eye of a camera. For to thumb through Robert Frank’s 1958 collection of road images, The Americans, is to have one’s sense of what is visually important transformed. Forever.

THOSE WORDS OF DISDAIN, designed to consign its subject to the ash heap of history, are now forever attached to the photographic work that, instead of vanishing in disgrace, almost single-handedly re-invented the way the world saw itself through the eye of a camera. For to thumb through Robert Frank’s 1958 collection of road images, The Americans, is to have one’s sense of what is visually important transformed. Forever.

In the mid-1950’s, mass-market photojournalist magazines from Life to Look regularly ran “essays” of images that were arranged and edited to illustrate story text, resulting in features that told readers what to see, which sequence to see it in, and what conclusions to draw from the experience. Editors assiduously guided contract photographers in what shots were required for such assignments, and they had final say on how those pictures were to be presented. Robert Frank, born in 1924 in Switzerland, had, by mid-century, already toiled in these formal gardens at mags that included Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, and was ready for something else, a something else where instinct took preference over niceties of technique that dominated even fine-art photography.

Making off for months alone in a 1950 Ford and armed only with a 35mm Leica and a modest Guggenheim grant, Frank drove across much of the United States shooting whenever and wherever the spirit moved him. He worked quickly, intrusively, and without regard for the ettiquette of formal photography, showing people, places, and entire sub-cultures that much of the country had either marginalized or forgotten. He wasn’t polite about it. He didn’t ask people to say cheese. He shot through the windshield, directly into streetlights. He didn’t worry about level horizons, under-or-over exposure, the limits of light, or even focal sharpness, so much as he obsessed about capturing crucial moments, unguarded seconds in which beauty, ugliness, importance and banality all collided in a single second. Not even the saintly photojournalists of the New Deal, with their grim portraits of Dust Bowl refugees, had ever captured anything this immediate, this raw.

Frank escaped a baker’s dozen of angry confrontations with his reluctant subjects, even spending a few hours in local jails as he clicked his way across the country. The terms of engagement were not friendly. If America at large didn’t want to see his stories, his targets were equally reluctant to be bugs under Frank’s microscope. When it was all finished, the book found a home with the outlaw publishers at Grove Press, the scrappy upstart that had first published many of the emerging poets of the Beat movement. The traditional photographic world reacted either with a dismissive yawn or a snarling sneer. This wasn’t photography: this was some kind of amateurish assault on form and decency. Sales-wise, The Americans sank like a stone.

Around the edges of the photo colony, however, were fierce apostles of what Frank had seen, along with a slowly growing recognition that he had made a new kind of art emerge from the wreckage of a rapidly vanishing formalism. One of the earliest converts was the King of the Beats Himself, no less than Jack Kerouac, who, in the book’s introduction said Frank had “sucked a sad poem right out of America and onto film.”

Today, when asked about influences, I unhesitatingly recommend The Americans as an essential experience for anyone trying to train himself to see, or report upon, the human condition. Because photography isn’t merely about order, or narration, or even truth. It’s about constantly changing, and re-charging, the conversation. Robert Frank set the modern tone for that conversation, even if he first had to render us all speechless.

WRITE YOUR OWN STORY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE OLDEST CONSISTENT ROLE OF PHOTOGRAPHY IS AS NARRATIVE, its storytelling ability borrowed from painting but later freed, as painting would also be, from representations of mere reality. Before the beginning of the 20th century, photographs held moments, chronicled events, froze people in time. Over the next hundred tumultuous years, every part of the narrative process for all arts would be challenged, shattered and reassembled several times over. We pretend there are still rules that always apply to what an image says to us, but that is really only sentiment. Some photographs simply are.

What they are is, of course, both fun and infuriating for creator and audience alike. We wonder sometimes what we are supposed to think about a picture. We take comfort in being led a certain way, or in a set sequence. Look here first, then here, then here, and draw such-and-such a conclusion. But just as music need not relate a story in traditional terms (and often does not) the photograph should never merely present reality as a finished arrangement. The answer to the question, “what should I think about this?” can only be, whatever you find, whatever you yourself see.

I love having a clear purpose in a picture, especially pictures of people, and it has taken me years to make such images without the benefit of a deliberate road map. To arrange people as merely elements in a scene, then trust someone else to see what I myself cannot even verbalize, has forced me to relax my grip, to be less controlling, to have confidence in instincts that I can’t readily spell out in 25 words or less.

What are these people doing? What does their presence reveal beyond the obvious? Is there anything “obvious” about the picture at all? Just as a still life is not a commentary on fruit or a critique of flowers, some photographed people are not to be used in the service of a story. They can, in the imaginations of viewers, provide much more than that. Photography is most interesting when it’s a conversation. Sometimes that discussion takes place in strange languages.

YESTERGRUBBING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I ALWAYS SCRATCH MY HEAD WHEN I SEE AN EATERY sporting a sign that boasts “American Cuisine”, and often have to suppress an urge to step inside such joints to ask the proprietor to explain just what that is. If there is one thing about this sprawling broad nation that can’t be conveniently corralled and branded, it’s the act of eating. Riff through a short stack of Instagrams to see the immense variety of foodstuffs that make people say yum. And as for the places where we decide to stoke up….what they look like, how they serve us, how they feel….well, that’s a never-ending task, and joy, for the everyday photographer.

Eating is, of course, more than mere nourishment for the gut; it’s also a repast for the spirit, and, as such, it’s an ongoing human drama, constantly being shuffled and re-shuffled as we mix, mingle, disperse, adjourn and regroup in everything from white linen temples of taste to gutbucket cafes occupying speck of turf on endless highways. It’s odd that there’s been such an explosion of late in the photographing of food per se, when it’s the places where it’s plated up that hold the real stories. It’s all American, and it’s always a new story.

I particularly love to chronicle the diners and dives that are on the verge of winking out of existence, since they possess a very personalized history, especially when compared with the super-chains and cookie-cutter quick stops. I look for restaurants with “specialities of the house”, with furniture that’s so old that nobody on staff can remember when it wasn’t there. Click. I yearn for signage that calls from the dark vault of collective memory. Bring on the Dad’s Root Beer. Click. I relish places where the dominant light comes through grimy windows that give directly out onto the street. Click. I want to see what you can find to eat at the “last chance for food, next 25 mi.” Click. I listen for stories from ladies who still scratch your order down with a stubby pencil and a makeshift pad. Click. Click. Click.

In America, it’s never just “something to eat”. It’s “something to eat” along with all the non-food side dishes mixed in. And, sure, you might find a whiff of such visual adventure in Denny’s #4,658. Hey, it can happen. But some places serve up a smorgasbord of sensory information piping hot and ready to jump into your camera, and that’s the kind of gourmet trip I seek.

OH, SNAP

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MOST OF US ENTER PHOTOGRAPHY WITH THE SAME AIM, that is, to arrest the flight of something precious with the trick effect of having frozen time. Someone or something is passing through our life all too quickly, and we use our cameras to isolate small pieces of those passages like a butterfly inside an amber cube. That means that our first work is our most personal, and, while we may later graduate to more general, more abstract recordings of light, subject, and shape, we all begin by chronicling events of the most intimate nature.

And as we grow into more interpretative, less reportorial imaging, we also grow away from the clear, focused aim of that earlier work. Be it a triptych of a birthday, an anniversary, a wake or a christening, we understand clearly what a snap is for, what it was after. Its purpose and its message are unmistakable, something that cannot always be said for other kinds of photographs. Indeed, looking back on some of our own output at the distance of just a few years, we can actually be at a loss to explain what we were going after in a given photograph, what we were trying to say. This doesn’t happen with the snap. Its subject matter, and the degree to which we correctly captured it, is readily visible.

This may speak to why photographers are often asked why they don’t take “more pictures of people”, or, more specifically, why did you take a picture of this person? Do you know him? No? Then why……..?? It isn’t that a connection between yourself and people who are strangers to you can’t be made in a photograph. It’s that it’s a lot harder to effectively tell that story. it requires less from the camera and more from you.

You need to fill in a lot more blanks in a tale in which fewer elements are pre-provided. You can convey something universal about the human condition with a picture of something outside your own experience, certainly. It’s just that it’s easier to make the link that exists between you, your mother, her birthday, and her surrounding gang of friends than between yourself and someone who is essentially alien to you, or to the rest of us. Of course, on the other side of the ledger, you can also shoot a bajillion pictures of those closest to you, and still manage to convey nothing of their true selves. Mere technical acuity is not intimacy, or vision.

Still, in general terms, the snap deserves a lot more respect than it gets, simply because there is, in these personal images, a near-perfect match alignment of shooter, subject and clarity of purpose. By contrast, when we venture out into the greater world, trying to tell equally effective stories with much less information is hard. Not impossible, but, man, really hard.

MAKING LIGHT OF THE SITUATION

BY MICHAEL PERKINS

IN PORTRAITS, PHOTOGRAPHERS SOMETIMES HAVE TO SUBSTITUTE INTIMACY FOR TECHNICAL PERFECTION. We understandably want to come as near as possible to meticulously modulated light in telling the story of a face, and so we try to ride the line between natural, if inadequate light, and light which is shaped so much that we dull the naturalness of the moment.

It’s a maddening tug of war. If we don’t intervene, we might make an image which is less than flattering, or, worse, unfit for publication. If we nib in too much, we get a result whose beauty can border on the sterile. I find that, more often than not, I lean toward the technically limited side, choosing to err in favor of a studied snapshot rather than a polished studio look. If the face I’m shooting is giving me something real, I worry more about throwing a rock into that perfect pond with extra tinkering.

If my subject is personally close to me, I find it harder, not easier, to direct them, lest the quality I’m seeing in their natural state be replaced by a distancing self-consciousness. It puts me in the strange position of having to wait until the situation all but gifts me with the picture, as adding even one more technical element can endanger the feel of the thing. It’s times like this that I’m jammed nose-up against the limits of my own technical ability, and I feel that a less challenged shooter would preserve the delicacy of the situation and still bring home a better photograph.

In the above frame, the window light is strong enough to saturate the central part of my wife’s face, dumping over three-fourths of her into deep shadow. But it’s a portrait. How much more do I need? Would a second source of light, and the additional detail it would deliver on the left side of her head be more “telling” or merely be brighter? I’m lucky enough in this instance for the angle of the window light to create a little twinkle in her eye, anchoring attention in the right place, but, even at a very wide aperture, I still have to crank ISO so far that the shot is grainy, with noise reduction just making the tones flatter. It’s the old trade-off. I’m getting the feel that I’m after, but I have to take the hit on the technical side.

Then there was the problem that Marian hates to have her picture taken. If she hadn’t been on the phone, she would already have been too aware of me, and then there goes the unguarded quality that I want. I can ask a model to “just give me one more” or earn her hourly rate by waiting while I experiment. With the Mrs., not so much.

Here’s what it comes down to: sometimes, you just have to shoot the damned thing.

TAKE ME OUT TO THE “ALL” GAME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU SEE RIDICULOUS ARTICLES FROM TIME TO TIME claiming that baseball has been replaced as America’s Pastime. Such spurious scribblings invariably point to game attendance, TV ratings, or some other series of metrics that prove that football, basketball, and, who knows, strip Scrabble have reduced baseball to some quaint state of irrelevancy. All such notions are mental birdpoop for one salient reason. No one is giving due attention to the word pastime.

Not “passion”. Not “madness”. Not even “loyalty”. Pastime. A way of letting the day go by at a leisurely pace. A way to gradually unfurl afternoons like comfy quilts. People-watching. Memory. Sentiment. Baseball is for watchers, not viewers, something that television consistently fails to realize. It’s the stuff that happens in the pauses, of which the game has plenty. Enjoying baseball, and photographing it as an experience, is about what happens in the cracks.

Images are waiting to be harvested in the dead spots between pitching changes. The wayward treks of the beer guys. The soft silence of anticipatory space just before the crack of a well-connected pitch. TV insists on jamming every second of screen time-baseball with replays, stat tsunamis, and analysis. Meanwhile, “live”, in the stadium, the game itself is only part of the entertainment. Sometimes, it actually drops back to a distant second.

Only a small percentage of my baseball pictures are action shots from the field: most are sideways glances at the people who bring their delight, their dreams, and their drama to the game. For me, that’s where the premium stories are. your mileage may vary. Sometimes it’s what’s about to happen that’s exciting. Sometimes it’s the games you remember while watching this one. There are a lot of human factors in the game, and only some of them happen between the guys in uniform.

Photography, as a pastime, affords a great opportunity to show a pastime. America’s first, best pastime.

It’s not just a ballgame. It’s an “all” game.

Root, root, root.

EAVES-EDITING

by MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE SIDE BENEFITS OF PHOTOGRAPHY is that you don’t always have to pick your own subject. Sometimes someone else’s idea of a potentially good image can be yours as well. You simply camp yourself right next to where they’re working and pick off your own shots of their project. Assuming that everyone’s polite and there are no issues of neighborly nibbing, it can work. Just ask anyone who’s clicked away at a presidential press conference or the sudden exit of a celebrity through a side entrance.

Of course, when literally dozens of cameras are trained on a single event, its likely that everyone will come away with the same photos, or very nearly. The moment the prime minister points to drive home his main point, click. The instant when the judges place the tiara on the winning Miss Tomato Paste candidate, click. Sometimes, however, you can kind of “eaves-edit” on just one other shooter’s set-up and edit the shots a different way than he does. You’re not running the session, but you could come away with a better result than he does, based on your choices.

I recently came upon a man shooting a girl in the streets of a kind of faux-village retail environment in Sedona, Arizona. Obviously, the main feature was the lady’s infectious and natural smile. As I came quietly upon them, however, Mr. Cameraman was having a problem keeping that smile from exploding into a full-blown laughing fit. Ms. Subject, in short, had the mad giggles.

Now, from that point onward, I have no idea of what he went home with in the way of a final result, as I had decided that the crack-ups would make better pictures than a merely sweet set of candids. It just seemed more human to me, so I only shot the moments in which she couldn’t compose herself, and took off from there.

I didn’t want to overstay my welcome, so I snapped my little chunk of Mr. Cameraman’s moment and sneaked off, like fast. As I slinked away, I could still hear Ms. Subject telling him, through fits of laughter, “I am so sorry.” She may have been, but I wasn’t.

THE REVEAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS HAVE MANY INSTANCES IN WHICH IT’S HEALTHY TO HAVE A LITTLE HUMILITY, and the biggest one probably is in the decision to depict a human face. It’s the most frequently performed operation in all of photography, and many of us only approach perfection in it a handful of times, if ever. The face is the essence of mystery, and learning how to draw the curtain away from it is the essence of mastery.

Nothing else that we will shoot fights so hard to maintain its inscrutability. It is easier to accurately photograph the microbes that swarm in a drop of water than to penetrate the masks that we manufacture. Even the best portrait artists might never show all of what their subject’s soul really looks like, but sometimes we can catch a fleeting glimpse, and getting even that little peek is enough to keep you behind a camera for a lifetime. It is everything.

Yousuf Karsh, the portraitist who can be said to have made the definitive images of Winston Churchill, Audrey Hepburn, JFK, Ernest Hemingway, and countless other notables, said “within every man and woman. a secret is hidden, and, as a photographer, it is my task to reveal it if I can.” Sounds so simple, and yet decades can go into learning the difference between recording a face and rendering its truths. Sometimes I think it’s impossible to photograph people who are strangers to us. How can that ever happen? Other times I fear that it’s beyond our power to create images of those we know the most intimately. How can we show all?

The human face is a document, a lie, a cipher, a self-created monument, an x-ray. It is the armor we put on in order to do battle with the world. It is the entreaty, the bargain, the arrangement with which we engage with each other. It is a time machine, a testimony, a faith. Photographers need their most exacting wisdom, their most profound knowledge of life, to attempt The Reveal. For many of us, it will always remain that….an attempt. For a fortunate few, there is the chance to freeze something eternal, the chance to certify humanity for everyone else.

Quite a privilege.

Quite a duty.

JOY GENERATORS

I could pose this rascal all day long, but I can’t create what he can freely give me. 1/40 sec., f/3.2, ISO 500, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S A TITANIC CLICHE, BUT RESOUNDINGLY TRUE: if you want a child to reveal himself to you photographically, get out of his way.

The highly profitable field of child portrait photography is being turned on its head, or more precisely, turned out of the traditional portrait studio, by the democratization of image making. As technical and monetary barriers that once separated the masses from the elite few are vanishing from photography, every aspect of formal studio sittings is being re-examined. And that means that the $7.99 quickie K-Mart kiddie package is going the way of the dodo. And it’s about bloody time.

Making the subject fit the setting, that is, molding someone to the props, lighting or poses that are most convenient to the portraitist seems increasingly ridiculous. Thing is, the “pros” who do portrait work at the highest levels of the photo industry have long since abandoned these polite prisons, with Edward Steichen posing authors, politicians and film stars in real-life settings (including their own homes) as early as the 1920’s, and Richard Avedon pulling models out of the studio and into the street by the late 1940’s. So it’s not the best photographers who insist on perpetuating the restrictive environment of the studio shoot.

No, it’s the mills, the department and discount stores who still wrangle the kiddies into pre-fab backdrops and watch-the-birdie toys, cranking out one bland, safe image after another, and veering the photograph further and further from any genuine document of the child’s true personality. This is what has to change, and what will eventually result in something altogether different when it comes to kid portraiture.

Children cannot convey anything real about themselves if they are taken out of their comfort zones, the real places that they play and explore. I have seen stunning stuff done with kids in their native environment that dwarfs anything the mills can produce, but the old ways die hard, especially since we still think in terms of “official” portraits, as if it’s 1850 and we have a single opportunity to record our existence for posterity. There really need be no “official” portrait of your child. He isn’t U.S. Grant posing for Matthew Brady. He is a living, pulsating creature bent on joy, and guess what? You know more about who and what he is than the hourly clown at Sears.

I believe that, just as adult portraiture has long since moved out of the studio, children need also to be released from the land of balloons and plush toys. You have the ability to work almost endlessly on getting the shots of your children that you want, and better equipment for even basic candids than have existed at any other period in history. Trust yourself, and experiment. Stop saying “cheese”, and get rid of that damned birdie. Don’t pose, place, or position your kids. Witness these little joy generators in the act of living. They’ll give you everything else you need.

YOU’RE GREAT, NOW MOVE, WILLYA?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF MY FAVORITE SONGS FROM THE ’40’s, especially when it emanates from the ruby lips of a smoking blonde in a Jessica Rabbit-type evening gown, conveys its entire message in its title: Told Ya I Love Ya, Now Get Out! The hilarious lyrics speak of a woman who acknowledges that, yeah, you’re an okay guy, but don’t get needy. No strings on me, baby. I’ll call you when I want you, doll. Until then, be a pal and take a powder.

I sometimes think of that song when looking for street images. Yes, I’m aware that the entire sweep of human drama is out there, just ripe for the picking. The highs. The lows. Thrill of victory and agony of de feet. But. I always feel as if I’m cheating the world out of all that emotional sturm und drang if I want to make images without, you know, all them people. It’s not that I’m anti-social. It’s just that compelling stuff is happening out there that occasionally only gets compromised or cluttered with humans in the frame.

Scott Kelby, the world’s biggest-selling author of photographic tutorials, spends about a dozen pages in his recent book Photo Recipes showing how to optimize travel photos by either composing around visitors or just waiting until they go away. I don’t know Scott, but his author pic always looks sunny and welcoming, as if he really loves his fellow man. And if he feels it’s cool to occasionally go far from the madding crowd, who am I to argue? There are also dozens of web how-to’s on how to, well, clean up the streets in your favorite neighborhood. All of these people are also, I am sure, decent and loving individuals.

There is some rationality to all this, apart from my basic Scrooginess. Photographically, some absolutes of abstraction or pure design just achieve their objective without using people as props. Another thing to consider is that people establish the scale of things. If you don’t want that scale, or if showing it limits the power of the image, then why have a guy strolling past the main point of interest just to make the picture “human” or, God help us, “approachable”?

Faces can create amazing stories, imparting the marvelous process of being human to complete scenes in unforgettable ways. And, sometimes, a guy walking through your shot is just a guy walking through your shot. Appreciate him. Accommodate him. And always greet him warmly:

Told ya I love ya. Now get out.

TELLING THE TRUTH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PICK ANY PHOTOGRAPHIC ERA YOU LIKE, and most of the available wisdom (or literature) will concentrate on honoring some arbitrary list of rules for “successful” pictures. On balance, however, relatively few tutorials mention the needful option of breaking said rules, of making a picture without strict adherence to whatever commandments the photo gods have handed down from the mountain. It’s my contention that an art form defined narrowly by mere obedience is bucking for obsolescence.

It’d be one thing if minding your manners and coloring inside the lines guaranteed amazing images. But it doesn’t, any more than the flawless use of grammar guarantees that you’ll churn out the great American novel. Photography was created by rebels and outlaws, not academics and accountants. Hew too close to the golden rules of focus, exposure, composition or subject, and you may inadvertently gut the medium of its real power, the power to capture and communicate some kind of visual verity.

A photograph is a story, and when it’s told honestly, all the technical niceties of technique take a back seat to that story’s raw impact. The above shot is a great example of this, although the masters of pure form could take points off of it for one technical reason or another. My niece snapped this marvelous image of her three young sons, and it knocked me over to the point that I asked her permission to make it the centerpiece of this article. Here, in an instant, she has managed to seize what we all chase: joy, love, simplicity, and yes, truth. Her boys’ faces retain all the explosive energy of youth as they share something only the three of them understand, but which they also share with anyone who has ever been a boy. This image happens at the speed of life.

I’ve seen many a marvelous camera produce mundane pictures, and I’ve seen five-dollar cardboard FunSavers bring home shots that remind us all of why we love to do this. Some images are great because we obeyed all the laws. Some are great because we threw the rule book out the window for a moment and just concentrated on telling the truth.

You couldn’t make this picture more real with a thousand Leicas. And what else are we really trying to do?

STEALTH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AT A PARTY, THERE ARE DISTINCT ADVANTAGES TO NOT BEING AN “OFFICIAL” PHOTOGRAPHER. You could probably catalogue many of them yourself with no strain. Chief among the perks of being an amateur (can we get a better word for this?) is that you are the captain of your own fate. You shoot what you want, when you want. Your arrival on the scene is not telegraphed by stacks of accompanying cases, light fixtures, connecting cords or other spontaneity killers that are essential to someone who has been “assigned” to an event. Your very unimportance is your license to fly, your ticket to liberation. Termed honestly (if unkindly), your work just doesn’t matter to anyone else, and so it can mean everything to you. Yay.

One of the supreme kicks I derive from going to events with my wife is that I can make her forget I’m there. I mean, as a guy with a camera. She has the gift of being able to submerge completely into the social dynamics of wherever she is, so she is not thinking about when I may elect to sneak up and snap her. Believe me, when you live with a beautiful woman who also hates to have her picture taken, this is like hitting the trifecta at Del Mar. At 20 to 1.

Free from the constraints of being “on the job”, I enjoy a kind of invisibility at parties, since I use the fastest lenses I can and no flash, ever, ever, ever. I do not call attention to myself. I do not exhort people to smile or arrange them next to people that they may or may not be able to stand. The word “cheese” never leaves my lips. I take what the moment gives me, as that is often richer than anything I might concoct, anyway. Working with a DSLR is a little more conspicuous than the magical invisibility of a phone camera, which people totally ignore, but if I am cagey, I can work with an “official” camera and not be perceived as a threat. Again, with a woman who (a) looks great and (b) doesn’t like how she looks in pictures, this is nirvana.

Candid photography is all about the stealth. It’s not about warning or prepping people that, attention K-Mart shoppers, you’re about to have your picture took. The more you insert yourself into the process (look over here! big smiiiiile!) the more you interrupt the natural rhythm that you set out to capture. So stop working against yourself. Be a happy sneak thief. Like me.

ACCUMULATIONS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

STREET PHOTOGRAPHY CONSISTS MOSTLY OF SHOWING PEOPLE in the full context of their regular worlds.

In terms of portraits or candids, it’s usually sufficient to showcase those we know in controlled environments….family gatherings, special occasions, a studio setting. However, to reveal anything about the millions of strangers we encounter over a lifetime, we only have context to show who they are and what they do. To say something about these fascinating unknowns, we truly need the “props” that define their lives.

I never thought it was that profound to just snap a candid of someone walking down the street. Walking to where? To do what? To meet whom? Granted, a person composed as part of an overall street scene can be a great compositional elements all by him/herself, but to answer the question, who is this person? requires a setting that fixes him in time, in a role or a task. Thus pictures of people doing something, i.e., being in their private universe of tools, objects, and habits…now that can make for an interesting study.

We now have successful reality TV shows like Somebody’s Gotta Do It which focus on just what it’s like to perform other people’s jobs, the jobs we seldom contemplate or tend to take for granted. It satisfies a human curiosity we all share about what else, besides ourselves, is out there. Often we try to gain the answer by sending probes to the other side of the galaxy, but, really, there’s plenty to explore just blocks from wherever we live. Thing is, the people we show make sense only in terms of the accumulations of their lives…the objects and equipment that fill up their hour and frame them in our compositions.

The legendary Lewis Hine made the ironwalkers of Manhattan immortal, depicting them in the work of creating the city’s great skyscrapers. Others froze workers and craftsmen of every kind in the performance of their daily routines. Portraits are often more than faces, and showing people in context is the real soul of street photography.

QUICK, NOBODY POSE

Even at the Los Angeles Zoo, the most interesting animals are on the opposite side of the bars. 1/80 sec., f/4, ISO 200, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR PHOTOGRAPHERS, HARNESSING THE NATURAL ENERGY OF A CHILD is a little like flying a kite during a thunderstorm was for Ben Franklin. You might tap into a miraculous force of nature, but what are you going to do with it? Of course, there’s big money in artificially arranging light and props for formalized (or rather, idealized) portraits of kids. It’s a specialty art with specific rules and systems, and for proud parents, it’s a steady market. We all want our urchins “promoted” to angel status, albeit briefly. However, in terms of photographic gold, you can’t, for my money, beat the controlled chaos of children at play. It’s street photography with an overlay of comedy and wonder.

However, attempting to extract a miracle while watching kids be kids is like trying to capture either sports or combat, in that it has a completely different dynamic from second to second, so much so that you should be prepared to shoot a lot, shifting your focus and framing on the fly, since the center of the action will shift rapidly. I don’t necessarily believe that there is one decisive moment which will explain all aspects of childhood since the creation of the world, but I do think that some moments have a better balance between sizes, shapes, and story elements than others, although you will be shooting instinctively for much of the time, separating the wheat from the chaff later upon review of the results.

As with the aforementioned combat and sports categories, the spirit that is caught in a shot supersedes technical perfection. I’m not saying you should throw sharpness or composition to the wind, but I think the immediacy of some images trumps the controlled environment of the studio or a formal sitting. Some artifacts of blur, inconsistent lighting, or imprecise composition can be overlooked if the overall effect of the shot is truthful, visceral. The very nature of candid photography renders all arbitrary rules rather useless. The results justify themselves regardless of their raggedness, whereas a technically flawless shot that is also bloodless can never be justified on any grounds.

Work the moment; trust it to develop naturally; hitch a ride on the wave of the instantaneous.

PUBLIC INTIMACY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

OKAY, I JUST REALIZED HOW GROSSLY MISLEADING THE TITLE OF THIS POST COULD SEEM, but, trust me, I never meant it the way it sounds. I was just struggling to find a phrase for the kind of photograph in which a person is as private as possible while on full display to the world at large. There are behaviors that are intensely personal and astonishingly public at the same time, and such events in a human being’s life are rife, for the photographer, with a very singular kind of drama.

We like to think of ourselves as sufficiently camouflaged behind the carefully crafted mask that we present for the public’s consumption, all the better to preserve our sense of privacy. But there are always cracks in the mask, fleeting signals at the raw life underneath. Learning to detect those cracks is the talent of the street photographer, whose eye is always trained beyond the obvious.

Mourning, Joy, Discovery…all these things provide a teeter-totter balance between public display and private truth. The primal basics of life bring that juggling act into view, and, as a photographer, I am often surprised how much of them is in evidence in the simple act of nourishing ourselves. Dining would seem, on the surface, to be all about simple survival. Eating to live, and all that. But meals are laden with ritual and habit, the most hard-wired parts of one’s personality. Food gathers people for so much more than mere sustenance. It is memory, community, religion, friendship, negotiation, reassurance, replenishment. It is a symbol for life (and its passing), a trigger for shared experience, a talisman, a consecration.

Case in point: the man and woman in the above image were seen in a Los Angeles restaurant late on a Saturday night. Their relationship would seem to be that of mother and son, but it could be grandmother and nephew, son-in-law and mother-in-law, or a dozen other arrangements. A sharp contrast is provided by their comparative ages and physicality. One sits upright, while the other sits as well as she can. There is no eye contact….but does that necessarily mean that they do not want to see each other? There is no conversation. Has everything already been said? Are they grateful to still be there for each other after all these years, or is this the fulfillment of an obligation, a visitation occasioned by guilt?

Eating is a microcosmic examination of everything that it means to be human. So much for a single photographic frame to try to capture. So many ways of looking into the publicness of privacy.

THE UNRESOLVED RIDDLE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A RECENT PIECE BY TIMOTHY EGAN IN THE NEW YORK TIMES decried the latest innovation in Instagram etiquette, a device called a “selfie stick”. As the name implies, the stick is designed to hold one’s smartphone at a modest distance from its subject (me!) allowing oneself to be better framed against larger scenes, such as landscapes, local sights, etc. Egan mostly ranted against the additional invasion of public peace by armies of narcissistic simps who couldn’t be persuaded to merely be in the moment, unless they could also be in the picture. It struck him as a fresh assault on “real” experience, another example, as if we needed one, of our sadly self-absorbed age.

I agree with most of Egan’s epistle, but I think the real tragedy is that the selfie stick allows us to take more, more, more pictures, and reveal less, less, less of the people that we truly are. Selfies are more than emotionally stunted; most of them are also lies, or, more properly, masks. They are not “portraits” any more than they are steam shovels, as they merely replicate our favorite way of distancing ourselves from discovery… the patented camera smile. Frame after frame, day after endless day, the tselfie tsunami pushes any genuine depiction of humanity farther away, substituting toothpaste grins for authentic faces. Photographs can plumb the depths of the spirit, or they can put up an impenetrable barrier to its discovery, like the endless string of forced “I was here” shots that we now endure in every public place.

There’s a reason that the best portraits begin with not one lucky snap but dozens of “maybes”, as subject and photographer perform a kind of dance with each other, a slow wrestling match between artifice and exposition. Let’s be clear: just because it is easier,mechanically, to capture some kind of image of ourselves doesn’t mean we are getting any closer to the people we camouflage beneath carefully crafted personae. Indeed, if a person who acts as his own lawyer “has a fool for a client”, then most of us have a liar in charge of telling the truth about ourselves. Merely larding on additional technology (say, a stick on a selfie) just allows a larger portion of our false selves to fit into the picture, while the puzzle of who that person is, smirking into the camera, remains, all too often, an unresolved riddle.

THE BOY IN THE BALL CAP

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MORE SHOTS, MORE CHOICES: Photography really is as simple as that. The point has been hammered home by expert and amateur alike since before we could say “Kodak moment”: over-shooting, snapping more coverage from more vantage points, results in a wider ranger of results, which, editorially, can lead to finding that one bit of micro-mood, that miraculous mixture of factors that really does nail the assignment. Editors traditionally know this, and send staffers out to shoot 120 exposures to get four that are worthy of publication. It really, ofttimes, is a numbers game.

For those of us down here in the foot soldier ranks, it’s rare to see instances of creative over-shoot. We step up to the mountain or monument, and wham, bam, there’s your picture. We tend to shoot visual souvenirs: see, I was there, too. Fortunately, one of the times we do shoot dozens upon dozens of frames is in the chronicling of our families, especially the day-to-day development of our children. And that’s vital, since, unlike the unchanging national monument we record on holiday, a child’s face, especially in its earlier years, is a very dynamic subject, revealing vastly different features literally from frame to frame. As a result, we are left with a greater selection of editing choices after those faces dissolve into other faces, after which they are gone in a thrilling and heartbreaking way.

One humbling thing about shooting kids is that, after they have been around a while, you realize that you might have caught something essential, months or years ago, during an event at which you just felt like you were reacting, racing to catch your quarry, get him/her in focus, etc. A feeling of always trying to catch up. It’s one of the only times in our own lives that we shoot like paparazzi. This might be something, better get it. I’ll sort it out later. The process is so frenetic that some images may only reveal their gold several miles down the road.

Not the sharpest image I ever shot, but look at that face. Slow shutter to compensate for the dim light. 1/40 sec., f/3.2, ISO 200, 35mm.

My grandson is now entering kindergarten. He’s reading. He’s a compact miniature of his eventual, total self. And, in recently riffing through images of him from early five years ago (and yes, I was sniffling), I found an image where he literally previews the person I now know him to be. This image was always one of my favorite pictures of him, but it is more so now. In it, I see his studious, serious nature, and his intense focus, along with his divine vulnerability and innocence. Technically, the shot is far from perfect, as I was both racing around to catch him during one of his impulse-driven adventures and trying to master a very new lens. As a result, his face is a little soft here, but I don’t know if that’s so bad, now that I view it with new eyes. The light in the room was itself pretty anemic, leaking through a window from a dim day, and running wide open on a 50mm f/1.8 lens at a slow 1/40 was the only way I was going to get anything without flash, so I risked misreading the shallow depth of field, which I kinda did. However, I’ll take this face over the other shots I took that day. Whatever I was lacking as a photographer, Henry more than compensated for as a subject.

Final box score: the boy in the ball cap hit it out of the park.

Thanks, Hank.

WAIT FOR IT…..

by MICHAEL PERKINS

SUNDAY MORNINGS AT THE LOS ANGELES COUNTY MUSEUM OF ART ARE A GAGGLE OF GIGGLES, a furious surge of activity for, and by, little people. Weekly craft workshops at LACMA are inventive, inclusive, and hands-on. If you can cut it, fold it, glue it, paint it, or assemble it, it’s there, with booths that feature encouraging help from slightly larger people and smiles all around. It is a fantastic training ground as well for photographing kids in their natural element.

A recent Sunday featured the rolling out of long strips of art paper into rows along one of the common sidewalks, with museum guides on bullhorn exhorting the young to create their own respective visions with paint and brush. The event itself was rich in possibility, as a hundred little dramas and crises unfolded along the wide, white canvasses. Here a furrowed brow, there an assist from Mom. Fierce concentration. Dedication of purpose. Sunshaded Picassos-in-waiting weighing the use of color, stroke, concept. A mass of masters, and plenty of chances for really decent images.

Most of these events are as fast as they are furious, and so, during their brief duration, you can go from photographic cornucopia to….where did everybody go? Sometimes it’s over so quickly that it’s really tempting to treat the entire thing like low-hanging fruit: a ton of kids pass before your eyes in a few minutes’ time, and you have only to stand and click away. Thing is, I’m a lifelong believer in arriving early and leaving late, simply because the unexpected bit of gold will drop into your lap when you troll around before the beginning or after the end of things. In the case of this museum “paint-in”, the participants scampered on to the next project in one big sweep, leaving their artwork behind like a ruined battlefield. And then, miracle of miracles, one lone girl wandered into the near center of this huge Pollack panorama and sat herself down. The event was over but the vibe was revived. I whispered thank you, photo gods, and framed to use the paintings as a visual lead-in to her. It couldn’t have been simpler, luckier, or happier.

When the “stage” on public events is being either set or struck, there are marvelous chances to peer a bit deeper.People are typically relaxed, less guarded. The feel of everything has an informality, even an intimacy. And sometimes a small child brings the gift of her spirit into the frame, and you remember why you keep doing this.

ANTHROPOGRAPHY

Tuning up: a fiddler runs a few practice riffs before a barn dance in Flagstaff, Arizona.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WRITING CLICHE NUMBER 5,218 STATES THAT YOU SHOULD WRITE about what you know. Mine your own experience. Use your memories and dreams as a kickoff point for the Great American Novel, or, at least, the Okay American E-book. But while the “know-it-do-it” school of technique offers writers a pretty sound foundation for scribblers, photographers need to learn how to leave their native nests and fly into unknown country. The best pictures sometimes are where you, comfortably, aren’t.

Caperin’ up a storm, by golly.

Shooting an event or lifestyle that is completely outside yourself confers an instantaneous objectivity of sorts to your pictures, since you don’t have any direct experience with the things you’re trying to capture. You’re forced to pretty much go instinctive, since you can’t draw on your memory banks. This is certainly true of combat photographers or people dropped down into the middle of fresh disasters, but it also works with anything that’s new to you.

Take square-dancing. No, I mean it. You take square-dancing, as in, I’d rather be covered in honey and hornets than try to master something that defines “socially awkward” for yours truly. I can’t deny that, on the few occasions that I’ve observed this ritual up close, it obviously holds infinite enjoyment for anyone who isn’t, well, me. But being me is the essential problem. I not only possess the requisite two left feet, I am lucky, on some occasions to even be ambulatory if the agenda calls for anything but a rote sequence of left-right-left. Again, I concede that square-dancers seem almost superhumanly happy whenever doing their do-si-doing, and all props to them. Personally, however, I can cause a lot less damage and humiliation for all concerned if I bring a camera to the dance instead of a partner.

Shooting something you don’t particularly fancy yourself is actually something of an advantage for a photographer. It allows you to just dissect the activity’s elements, using the storytelling techniques you do know to show how the whole thing works. You’re using the camera to blow apart an engine and see its working parts independently from each other.

In either writing or shooting, clinging to what you know will keep your approach and your outcomes fairly predictable. But when photography meets anthropology, you can inch toward a little personal growth. You may even say “yes” when someone asks you if you care to dance.

Or you could just continue to maintain your death grip on your camera.

Yeah, let’s go with that.

Share this:

September 25, 2015 | Categories: Americana, Black & White, Candid, Conception, iPhone, Musical Instruments | Tags: Composition, crowds, Entertainment, Music, social commentary | Leave a comment