FAILING TO SEE THE BIG PICTURE

This image lingered in the “maybe” pile for a while. Then I started to see how much of it was expendable (see below).

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S ENTIRELY POSSIBLE THAT MANY A WORKABLE PHOTOGRAPH HAS ONLY BEEN RENDERED SO BECAUSE OF SHEER BOREDOM. Face it: there are bound to be days when nothing fresh is flowing from one’s fingers, when, through lack of anything else to do, you find yourself revisiting shots that you 1) originally ignored, 2) originally rejected, or 3) were totally confounded by. Poring over yester-images can occasionally reveal something salvageable, either through processing or cropping, just as they can more often lead one to want to seal them up behind a wall. Even so, editing is a kind of retro-fitted variation on composition, and sometimes coming back around to a picture that was in conceptual limbo can yield a surprise or two.

I’m not suggesting that, if you stare long enough at an image, a little golden easter egg will routinely emerge from it. No, this is where luck, accident, and willpower usually converge to sometimes produce…..a hot mess, and nothing more. But leaving a picture for a while and returning to it makes you see with the eye of the outsider, and that can potentially prove valuable.

In the above shot, taken a few months go, I had all this wonderful gridded shadow texture presenting itself, shading what was otherwise a very ordinary stretch of sidewalk. A thought emerged that the stripes in the woman’s short might make an interesting contrast with the pattern of the shadows, but, after cranking off a frame or two, I abandoned the idea, just as I abandoned the shot, upon first review.

Months later, I decided to try to re-frame the shot to create a composition of one force against another…..in this case, the verticality of the lady’s legs against the diagonal slant of the shadows. That meant paring about two-thirds of the image away. Originally I had cropped it to a square with her lower torso at dead center, but there seemed to be no directional flow, so I cropped again, this time to a shorter, wider frame with the woman’s form reduced to the lower half of her legs and re-positioned to the leftward edge of the picture. Creating this imbalance in the composition, which plays to the human habit of reading from left to right along horizontal lines, seemed to give her a sense of leaving the shadows behind her, kind of in her wake if you will. At least a little sense of movement had been introduced.

I felt that now, I had the tug of forces I had been seeking in contrasting her blouse to the opposing grid in the master shot. I’m still not sure whether this image qualifies as having been “rescued”, but it’s a lot less busy, and actually directs the eye in a specific way. It will never be a masterpiece, but with the second sight of latter-day editing, you can at least have a second swipe at making something happen.

TONAL RECALL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF YOU WANT TO GET ALL MYSTICAL AND OOKY-SPOOKY ABOUT PHOTOGRAPHY, you can almost talk yourself into the idea that pictures kind of force their way past you on the way to their eventual best form. And, yes, I can hear your eyes rolling back in your head at the notion that an image is somehow destined to be created, that it emerges from your process almost despite you, like a rock that is pushed up through the earth by shifting tectonic plates. However, I have taken a handful of such pictures over a lifetime, as, no doubt, have you yourself, pictures that seemed to keep coming forth even beyond your first false steps until they reached their fullest expression.

Gee, is that incense I smell? Ommmmmm….

What I’m fumbling for here is a shared experience, and I do think that every photographer has had a semi-magical instance in which a photo almost taunts you to figure out how to make it work. Even in the best shots, there are moments of aching regret, maybe years down the path, that, had one or more things gone differently in the picture, it might have been eloquent or consequential. I truly believe that this very “so near, yet so far” quality is what keeps us in the hunt. After all, for the hunter, it’s the tiger he hasn’t been able to bag that calls louder than the ones already mounted over the mantel. So with photos. We are always singing the blues about the one that got away.

That’s why I’m a big believer in thinking of images as never really finished. They are, at best, preliminary studies for something else, picture that we still need to grow in order to complete. We lay them down, dissect them, re-shoot, re-imagine, and re-edit them. If you bend your thinking around, you can become comfortable with the fact that everything is a dress rehearsal for something that hasn’t arrived yet.

One of the starkest demonstrations of this fact is shots that were originally conceived as color images but which were later re-thought in monochrome. Nothing accentuates or streamlines your choices like shaving your tonal palette to the bare minimum. And, in the same vein, nothing makes you surer (or more unsure) about an image than reducing it to its simplest terms.

I think that, even as we are constantly expanding our arsenal of visual techniques, seeing them as growing, living things, so too we must think of our images as points on an evolutionary line, rather than final product.

LAYERS OF LEARNING

I have had to change my approach to flowers over a lifetime, and I still don’t “get” them in a real way.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS A YOUNG PIANO STUDENT, I NOTICED THAT MANY OF MY FAVORITE SHORT WORKS all bore the elegant, mysterious name of etude. It was somewhat later that I realized that this was merely the French word for a “study”, and that some of what I regarded as highly developed, final compositions were, essentially, first versions, practice runs by the masters in search of some eventual greatness. And, since I was an illustrator as well as a musician, the idea of an etude as a prototype, a first version of something dovetailed nicely with the idea of a sketch, or as my father called it, a “rough”. An etude was a work in progress.

Then came photography and, with it, the giddy short-term gratification of just snapping a picture, of crossing a visual item off one’s to-do list. We are, as humans naturally attracted to the process of completion, of turning out a finished product. Click. Done. Moving on….However, despite what the auction houses and gallery curators of the world might try to tell you, art is not a product, and just like those melodiously wondrous etudes, the best images are always in the process of being created. You can always take a picture to another level, but you can’t finish it.

Walk across to the painters’ side of the Art building every once in a while and look at how many preliminary studies Leonardo or Michelangelo made of their greatest works, or the number of “early” and “late” versions there are of these same masterpieces. Now, travel back to the photography wing and witness Ansel Adams taking one crack after another at the same stony face of El Capitan, often merely reworking the same master negative up to a half dozen times over decades. You simply have to make different pictures of the same subjects across a lifetime, just because your idea of what’s important to show keeps evolving.

Finally, look objectively at your own output and discover how many of your older images are “good pictures” and how many are good ideas for pictures. You’ll no doubt find your own personal “etudes”, the studies that can still become something better. In my own case, I have to walk away from floral subjects from time to time, then return to approach them with a different mindset, since I’m equally fascinated and clueless as to how to imbue them with anything approaching soulfulness. My eye struggles to make something magical emerge from buds and bouquets as others have done. But I’ll stay at it.

Digital processes make it possible to crank through a wide variety of approaches to the same subject in a very short span of time compared to film-based techniques. Think easy-fast-cheap. Or think good-better-best if you like. Either way, the layers of learning are stacked ever higher and deeper, allowing us to regard photography as process instead of product. So do your scales every day, keep your fingers high and curved, and stay curious.

ALONE AGAIN, UNNATURALLY

Lunch For One, 2011. Your choices as a photographer will determine if the woman in the cafeteria is alone…or lonely.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PEOPLE ARE ONE OF THE MOST COMPLICATED ELEMENTS in a photographic composition. Unlike furniture, foliage or flotsam, humans are the one “prop” in an image which convey associations and meanings that render a photo complex, troubling, intriguing. Put a person in your picture and you have changed the terms upon which you engage the audience.

At the very least, you have posed a series of questions which color the viewer’s reaction to your work. What is that person doing there? What does he wish for, or intend? What are his dreams, his goals? Is she merely in the picture, or in some way a commentary on her context within it? You can move things around in the name of composition alone, but move a person and you have started a conversation.

The placement of people in a frame creates speculation about the motives and origins of those people before they were in the frame. A man shown standing at the platform at a train station could be eagerly awaiting an arrival, sneaking out of town, or merely wandering around. The mind starts to supply his backstory, if you like, his actions before appearing in the finite world of the frame. Put two people side by side, and you have, according to your viewer’s whim, a rendezvous, a goodbye, a conspiracy, a reunion, a chance meeting. People change the perceived intention of a photograph as a storyboard, either in the original framing or in the cropping afterwards.

The above image is the final crop of what was, originally, a scenic overview, taken at a large campus of museum buildings on a hillside. The image, as first conceived, was an overall “postcard” with the restaurant in only the lower right quarter of the frame. Later, I became aware that a single woman was visible in the cafe. Now, it’s not that she was actually the only person inside, but the photograph could be cropped to make her seem like it, meanwhile accentuating the emptiness in her immediate area.

As a consequence, instead of a lady who is merely alone, the image can make her seem “lonely”. Or perhaps you disagree. The point is that, by changing the human information in the frame (note that, in the original of the cropped shot, there is also a man standing outside the restaurant), we’ve re-drawn its narrative.

What gets left out of a picture, then, sparks speculation by the viewer, based on what has been left in.

CASTING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MORE COMPOSITIONS IN PHOTOGRAPHY ARE CRAFTED AFTER THE SNAP than naturally spring forward, fully formed, out of the camera. Frame as carefully as you may, you often find that something needs to change to help your image’s story fully emerge. This usually means taking something away, cleaning things up…and that means cropping. I think it’s fair to say that, more often than not, we start with pictures that contain too much and carve out the core picture that deserves to survive, to be pushed to the front.

Sometimes a proportionate tightening is all that a picture needs, so that a large, busy rectangle becomes a streamlined, smaller rectangle. This can clear away extraneous objects like phone poles, wires, extra buildings, any distracting junk that pulls the eye away from the important stuff. But it isn’t always things: it can also be people, surplus bodies which, like extraneous elements of any kind, change the narrative, or keep it from connecting. Think of the picture as a theatrical production and yourself as the casting director. Anyone on the set who doesn’t move the story forward is not playing a part that we need. See the girl at the office for your check, so long.

In the picture above, the cropping seems to create the story of a mother and her children taking in the view from New York’s Highline Park onto a city street below. In the original shot, seen at left, she seems less like a mother and more like just another bystander. The crop has suggested a relationship or a role for her. The woman to her right (in the original), unlike the “mother” figure, is not acting as our surrogate, seemingly looking with us at the scene. She is on her cel phone, and therefore registers as more detached than her neighbor, whose face, since it’s invisible to us, could contain anything we want it to. To the right of the cel user, we see additional people who don’t subtract from the picture, but also don’t add anything. They are extras that we, the director, have decided we don’t need to cast.

Also, structurally speaking, the “mother” is arranged so that the diagonal line from the foreground building to her right seems to proceed into the picture from around the area of her right shoulder, so that she sort of anchors the leading line and sends your eye along it to the street below. None of this, mind you, was obvious in the shooting of the original shot, which is not terrible as a composition, only compromised by the inclusion of information that simply doesn’t advance the logic of the picture. I only use it as an example of how I was able to question the “casting” of the original frame and make a conscious decision to cut away things that slowed everything down.

If you can tell a story with two people better than you can with four or five, ask yourself if you really need them. Cropping isn’t an admission that you made a bad photograph. It’s confirmation that your first draft is worth taking to a second one.

POINTERS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WE ALL WENT THROUGH THAT OLD PERSPECTIVE EXERCISE IN ART 101. You know, the one where we draw the train tracks trailing away to an imaginary horizon, compressing the distance between the tracks as they “recede” to suggest depth, or a simulation of the way our eyes perceive it. It’s a lesson that dances somewhere back in our lizard brain whenever we compose a shot to suggest three dimensions on a flat plane (film or sensor) that only possesses two. Ongoing challenge, etc., etc.

In composing a photograph, it’s pretty easy to decide which factors in the picture actually aid that illusion, creating a big fat neon arrow to the thing we’re want to draw attention to. And some ways are better than others at selling that idea. One of the strong myths about these kinds of shots is that you need a wide-angle to make the argument for depth. Of course, that’s like a lot of “rules” in photography. It’s always true, except in those cases when it’s kinda…not.

In the top image, shot with a 24mm lens, the building at the back of the shot is lit better than the two alley walls that lead to it….a basic no-brainer of a composition. Moving left or right a bit can put the major emphasis on one wall or the other to be the arrow pointing to that object, or you can make the shot even more compact, although no less effective, in the cropping process.

Of the two walls, the rows of trash cans and receding lines of windows on the left seem, at least to me, to lead more powerfully to the back building than the right, where detail is darker and objects that could act as a leading line are a little more angled and compressed. Just for kicks, I cropped the shot to a square you see just above, reframing the back building as the end of a straight, single diagonal along the left wall, making the instruction to the eye a lot more streamlined.

It’s not that the fuller frame is “wrong” per se, but I always believe that inside many shots just might be a better shot waiting to get out. Some photographs are full-born in-camera, while others emerge during what I call the “on second thought” phase.

Now to try this idea out at a railroad crossing….

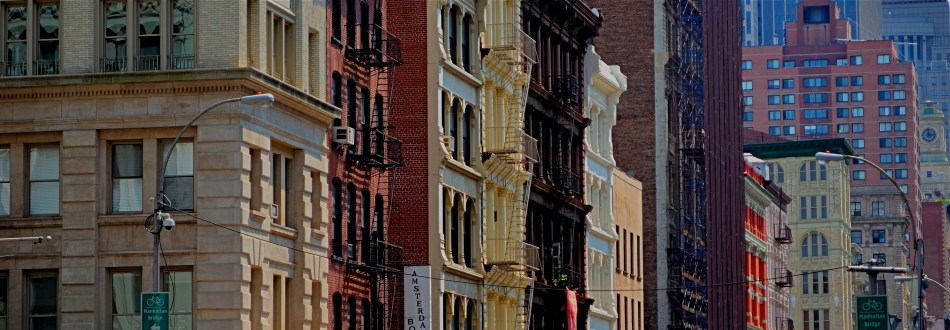

THE LONG AND SHORT OF IT

This original frame was just, um, all right, and I kept wanting to go back and find something more effective within it.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE INTRODUCTION OF THE FIRST PANORAMIC CAMERAS in the 1840’s can be seen as a freeing-up of the camera frame, a way to more accurately depict the entire field of view open to the human eye. And, of course that’s true. However, the first panos were also an early attempt by photographers to deliberately direct and orchestrate not only what you see, but how they want you to see it. Let’s concede that the western mind tends to absorb information in linear fashion. We read from left to right, we scan the horizon, and so forth. So making a photograph that instructs you to interpret horizontally is fairly natural.

So the first panos seem like a fairly modest extension of our visual bias. But think about the fundamental change that represented. Suddenly, photographers were saying, there are no rules except the rules I dictate. I decide what a frame is. I arrange not only the information inside the frame, but the frame itself. By re-shaping the box, I re-shape what you are to think about what’s in the box. That’s revolutionary, and today’s shooters would be wise to be mindful of that wonderful power.

I am fond of making what I will generously call “carved” panoramics, shots that began as standard framings but which I have cropped to force a feel of left-to-right linearity. Unlike standard panoramics, the shots were conceived and made with a very different compositional strategy, not necessarily trying to tell a horizontal story. However, on review, some stories-within-stories contain enough strong information to allow them to stand as new, tighter compositions in which the new instruction to the viewer’s eye is quite different from that in the original.

The full shot seen at the top of this page may or may not succeed as a typical “urban jungle” snap, in part because it contains both horizontal and vertical indices that can pull the eye all over the place. Since I wasn’t amazed by the shot itself, I decided to select a horizontal framing from its middle real estate that purposely directed the eye to laterally compare the facades of several different buildings stacked tightly down the street. Full disclosure: I also re-contrasted the shot to make the varying colors pop away from each other.

The result still may not be a world-beater, but the very act of cutting has re-directed the sight lines of the picture. For better or worse, I’ve changed the rules of engagement for the photograph. When such surgeries work, you at least fix the problem of extraneous clutter in your pictures, making them easier to read. Then it’s down to whether it was a good read or a beach read.

Hey, the box can’t fix everything.

THE OTHER TMI

Technical execution here is almost what’s needed, but the concept still needs work. Write the shot off to practice.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE WORST SOCIAL FAUX PAS OF OUR TIME may be the dreaded “TMI”, or the sin of sharing Too Much Information, creating awkward moments by regaling our friends with intimate details of our recent colostomies or carnal conquests. Funny thing is, much as we hate having this badge of uncoolness pinned to our chest, we commit its photographic equivalent all the time, and without a trace of shame.

I’m talking about the other TMI, or Too Many Images.

Let’s face it. Social media has encouraged too many of us to use the Web as a surplus warehouse dump for our photographs, many of them as ill-considered as a teenage girl’s hair flip. We’ve entered an endless loop of shoot-upload-repeat which seldom contains a step labeled “edit”. Worse, the vast storage space in our online photo vaults encourage us to share everything we shoot without so much as a backwards glance.

I’m suggesting that we take steps to stop treating the internet like an EPA Superfund site for images. I have tried to maintain a regular schedule of viewing the rearmost pages of my online archives, stuff from five years ago or longer, learning to ruthlessly rip out the shots that time has proven do not work. The goal is to force myself to re-think my original intentions and make every single photograph earn its slot in my overall profile. There are, by my calculation, three main sub-headings that these duds fall under:

The original idea for this shot is fairly strong, but my execution of it left something to be desired. Like execution.

A bad idea, well executed. Okay, you nailed the exposure and worked the gear to a “T”, but the picture has no story. There’s nothing being communicated or shared. Just because it’s sharp and well-lit doesn’t mean it deserves to stand alongside your stronger work.

A good idea, poorly executed. Hey, if you believe so strongly in the concept, go back and do it right. Don’t give yourself a pass on bad technique because it was a noble effort.

An incomplete idea, which means it wasn’t even time to take the picture at all. Maybe you didn’t know how to get your message across, for whatever reason. Or maybe if you got the conception 100% right, it still wasn’t strong enough to jump off the page. The litmus test is, if you wouldn’t want someone’s random search of your stuff to land on this shot instead of your best one, lose it.

Online stats make some of these tortured choices a bit easier, since, when you are looking at low figures on shots that have been available forever, it’s pretty clear that they aren’t lighting up anyone’s world. And as lame as view and fave counts can be, they are at least an initial signal pointer toward sick cows that need to be thinned from the herd. The cure for photographic “TMI” is actually as easy as shooting for long enough to get better. With a wider body of work viewed over time, the strong stuff stands out in bolder contrast to the weaker stuff. And that shows you where to wield the scissors.

SHOOT (AND THINK) BIG

The Nexus Of Resurrection, 2015. Image cropped from 4928 x 3264 pixels to 3550 x 1477, leaving enough density for a printable enlargement.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

BY NOW MOST OF US PROBABLY REALIZE THAT THERE IS NO REAL ADVANTAGE to “budgeting” shots in digital media the way we used to do in film. Harking back to the time of 24-exposure limits on one’s photographic fun, shooters maintained a running total in their heads of shots taken versus shots remaining, a cautious way of allocating frames on the fly, the idea being to finish the film roll and your tour stops at about the same time. Some kept notebooks; some doled out shots on a priority basis (one image of the waterfall, three of the ruins, four of the kids on the rides), and some, I suppose, were tempted to count on their fingers and/or toes. You had to be careful not to run out of frames.

Jump to the digital now, where we realize that, in all but the rarest cases, our shutter finger will crack and fall off before we “run out” of shots on even the most meager memory card. However, I still run into people who believe they are being prudent and providential by taking images at lower resolutions to “save space”, a false economy that is not only needless, but actually limits your options in the later process of editing.

Big files mean image density (lots o’ pixels) and therefore higher resolution. High resolution, in turn, means that you can crop substantial parts of a photo as needed and still have enough density for the image to hang together, even when printed out. Now, if you look at your work solely on a computer screen, protecting the integrity of a cropped image is less crucial, but if you’re lucky enough to create something you want to enlarge and frame, then you should begin with the fattest file you can get.

Review a few of your images that were, let’s say, less than compositionally sublime coming right out of the camera. Look at the pixel count on the same images after they were cropped to your liking. You’ll arrive at your own preference on what minimum resolution you’ll accept from the cropped versions. Thing is, the bigger you start, the more wiggle room you’ll have in editing.

As I say, most people already shoot at the largest file size possible. I merely send along this note to remind us all that we do it because it makes sense, and affords us real flexibility. It’s one of the amazing by-products of digital; we can, generally, shoot as much as we want for as long as we want.

TELL YOU WHAT’S BETTER….

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE AIM OF PHOTOGRAPHIC PROCESSING has shifted drastically in the post-digital age, and not necessarily in a good direction. Those of us old enough to remember mastadons, horse-drawn carriages and analog film were certainly aware that images could be edited or enhanced after the fact, conjuring up, say, memories of airbrush artists smoothing away chicken-pox scars from the shoulders of Miss January. We knew some of the magic happened in the lab.

Likewise, we knew that even the top masters did lots of tweaking in the darkroom prior to publication. The emphasis, however, was largely on perfecting an essentially strong picture, to make a good thing better/great. However, that emphasis is now placed, far too often, on trying to “save” images that were executed poorly in the first place, bringing marginal work up to some kind of baseline par of acceptability. That’s like the difference between polishing a Steinway and repainting a toy piano.

So, here’s my plea to those laboring to rescue their misbegotten babies in editing programs: Don’t repair. Re-shoot.

A good deal of the quick-fix buttons on editing programs should be marked with glowing red asterisks, with the following disclaimer at the bottom of the screen: WARNING: By using this change, you will fix your first proplem and create a different one somewhere else within your photograph. Let’s face it, no corrective action in editing happens in isolation. It must create a ripple effect, major or minor, in the final look of the image.

Use the “straighten” button for your misaligned shots, and they will lose sharpness. Suck out the darker shadows and your picture could lose dynamic range. Oversharpen your pictures and they will look harsh, with an unnatural transition between light and dark values. Reduce the noise in the image and it may appear flat, like pastel paint slathered on blotting paper.

Or here’s a radical notion: do all your thinking and planning before the shutter snaps. Yes, I know, I sound like some old schoolmarm scold, but please, can we at least consider the idea that there are no true shortcuts, that there can be no magical substitute for knowing your gear, developing an eye, and putting in the practice time required to make a photograph?

We once believed that patience was a virtue, that skill and mastery were more important than instant gratification. Know what? All of the greatest photographers still believe those things. And their work shows it.

ONE STORY AT A TIME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

BEING A MULTI-TASKER IS NO LONGER A MATTER OF CHOICE. We love to pretend that we’re adept at turning off selective parts of the hurricane of sensory input that comprises the whole of our daily life, but, fact is, we cannnot. You might be able to do as few as three things at a time in this world, but only if you struggle against a constant cacophony of sensations.

Unfortunately, creating art sometimes requires quiet, clarity, the ability to edit out unwanted sights and sounds in order to find a clear path toward a coherent vision. And this impacts photography as well as any other creative enterprise.

Urban life presents an especially big challenge to this urge to “get clear”, to untangle conflicting stories and draw out clean, direct messages for our images. Major cities are like 24-hour whistle factories, with thousands of things screaming for our attention. Thing is, there just isn’t enough attention to go around. Often, in poring over old projects, we find that a fourth, a third, even half of the information in a picture can be extracted in the editing process and still leave more than enough data to get our point across. And herein lies a problem.

If it’s getting harder and harder to edit in the moment to boil a photograph down to its essence, the editing phase becomes more crucial than ever before. You either get the best picture in the taking or in the remaking. It can be argued that practice helps the photographer learn to quickly ferret out simple stories within a mass of visual noise, and, of course, the more you shoot, the more you learn what not to shoot. But it seems inevitable that editing, and re-editing, will become a bigger part of the overall task of making pictures.

If the weakest of your photographic skills is post-processing, you might strongly consider upping that particular part of your game. The world isn’t slowing down anytime soon. It’s great to know, in an instant, how to make a strong image. But, as my dad always said, that’s why God put erasers on pencils. Editing can be where acceptable pictures buff up into contenders.

THE ABCs OF TMI

This street shot from a park in lower Manhattan is not ready for prime time, but it might get there with creative cropping.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR ME, ONE OF THE GREATEST ANCILLARY BENEFITS of doing historical research has been the privilege of poring over old files of newspaper and magazine photographs, in many cases viewing original, pre-publication master shots. It’s truly an exercise in reading between the “lines”, those hurried slashes of white grease pencil applied by editors as cropping instructions on shots that were too big, too busy, too slow in getting to the point. In many cases, you realize that, while the photographer may have taken the picture, it was the editor who found the picture.

Of course, no amount of cutting can improve a shot if there is not already a core story hiding within it. You can pare away the skin and seed of an apple, but some apples prove themselves rotten through and through. It’s the same with a photograph. However, if you teach yourself how to spot what, within a frame, is fighting with the central strength of a photo, it becomes obvious where to wield your scissors.

In the master shot image at top, the symmetry of the left and right groups of park visitors is blunted in its effect by the unneeded information along the top and bottom thirds of the frame. The shot is not really about the museum in the distance nor the ground in front of the benches. They just don’t help the flow of the picture, so losing them seems like the easiest way to boost the overall composition.

Now the shot is essentially a wide-angle, and, absent the earlier distractions, a kind of horseshoe curve emerges, tying the two benches together. You might even think of it as an arch shape, with the walking woman at the top acting as a keystone. She now draws attention first to the center, then around the curve, so that getting people to see what I am seeing becomes a lot easier. Finally, there is still a very loud distraction from the color in the shot, so a black-and-white remix keeps the reds and louder colors from “showing off” and lessening the impact of the story. The final result is still no masterpiece, but it does demonstrate that there was a very different picture hiding within the master shot, one that was certainly worth going after.

One of the downsides of being an amateur shooter is not reaping the benefit of a ruthless photo editor. However, learning to spot the weaknesses in potentially effective shots can be learned, most importantly the “ruthless” part. If you believe in an image, you won’t shy away from trimming its fingernails a bit to give it a chance to shine.

THE TAKEAWAY

The girl bathed in ceiling light is a nice start, but this picture needs some help to get where it’s going.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT IS SAID THAT THE GODDESS ATHENA WAS BORN, FULLY GROWN AND ARMORED, out of the forehead of Zeus. Other than being the only case where a man experienced anything that approached labor pain, the story always reminds me that ideas rarely arrive in their final form, especially in photography. If Athena had a Leica, she probably could have taken perfect shots without needing to compose or plan. We mere mortals are forced to either (a) report to hate-crazed photo editors, or (b) learn how to crop.

Many shots are created in stages, and there’s no shame in the game, since our original conception undergoes many phases from the first spark to something we’d actually hang on a wall. Creation itself is a process, which is why photographers should actually embrace the stages their work will pass through. The more thought that is applied to making an image, the better chance that the best way of doing something will reveal itself. Of course, it can also reveal the fact that there is nothing really to work with, in which case, hey, the bar should be open now, let’s go lick our wounds.

The original shot shown above is not yet a good photograph, but a good beginning for a  photograph. The lady bathed in light seems certainly to have been pre-selected to be the focal point of the picture, but there are way too many competing elements around her, robbing her of the prominence she deserves in the final frame. So let’s get after it.

photograph. The lady bathed in light seems certainly to have been pre-selected to be the focal point of the picture, but there are way too many competing elements around her, robbing her of the prominence she deserves in the final frame. So let’s get after it.

First, none of the information on the left side of the frame makes it any clearer that she’s alone or that she’s on the second floor of the building. We can make that plain with half the acreage, so snip. Similarly, the guys in shadow to her right aren’t part of the story we are crafting for her. If she’s isolated, let’s make her isolated and be unmistakable about it. She’s “apart” already from the sea of people below her. She’s geographically and physically separated from them, but the extra guys make the argument weaker, so, snip, away they go.

Finally, the entire upper-floor/lower-floor line of sight will be accentuated if we crop for a portrait orientation and move the frame so she is on the upper-right-hand corner of it. It forces the eye to discover the story of the picture vertically, so snip and we’re done.

So, at the end, we did not make any changes via processing, only the old scissors. Taking things away, not adding them on, actually made the picture work better. Fate gave me the girl and the wonderful light she was bathed in, but there was work to do. She didn’t arrive, ready to party, like Athena, but she’s a little closer to goddess status after some adjustment.

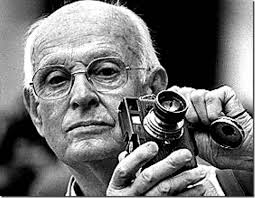

THE FLOATING 50

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU CANNOT BECOME A GREAT PHOTOGRAPHER WITHOUT BEING YOUR OWN BEST EDITOR, no matter how brilliant or instinctual your shooter’s eye may be. Art is both addition and subtraction, and the image frame is about both inclusion and exclusion. You get your viewers’ attention by knowing what to show. You hold that attention, and burn your images into their minds, by learning what to pare away.

I’ve written several variations on this theme, so the best way to restate it is in the voice of the truly visionary godfather of street photography, Henri Cartier-Bresson. Ironically, this master of in-camera composition (he is reputed never to have cropped a single shot after it was taken) was nonetheless remarkably aware of what most of us must do to improve an image through post-editing:

This recognition, in real life, of a rhythm of surfaces, lines, and values is for me the essence of photography; composition should be a constant of preoccupation, being a simultaneous coalition – an organic coordination of visual elements. We must avoid snapping away, shooting quickly and without thought, overloading ourselves with unnecessary images that clutter our memory and diminish the clarity of the whole.

Insert whatever is French for “Amen” here.

I often find that up to 50% of some of my original shots can later be excised without doing any harm to the core of the photograph, and that, in many cases, actually improving them. Does that mean that my original concept was wrong? Not so much, although there are times when that’s absolutely true. The daunting thing is that the 50% floats around. Sometimes you need to cut the fat in the edges: other times the dead center of the shot is flabby. Sometimes the 50 is aggregate, with 25% trimmed from two different areas of the overall composition.

On occasion, as with the above picture (see the original off to the left), the entire bottom half of the shot drags down the top. In the cropped shot, the long lateral line between indoors and outdoors is much more unbroken, making for a more “readable” shot from left to right. The disappearance of the dark furniture at the bottom of the master shot creates no problems, and actually solves a few. Do a disciplined search of the nobler near-misses in your own work and see how many floating 50’s you discover. Freeing your shots of the things that “clutter our memory and diminish the clarity of the whole” is humbling, but it’s also a revelation.

THE CENTER HOLDS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST FASCINATING PARTS OF THE LEGEND of Henri Cartier-Bresson, the artist who is the world’s model for street photography, is the oft-repeated story that he never cropped a shot over the many decades of his remarkable career. Thus the man who originated the phrase “the decisive moment” to indicate that there was but one ideal instant to capture something perfectly in the camera is also credited with creating flawless on-the-spot compositions, image after image, year after year. Yeah, well….

I love HCB, and I personally can’t find a single one of his images that I could improve upon, no matter where I was to wield my magic scissors. But just as the writer in me believes that great novels aren’t written, but re-written, I believe that many great photo compositions emerge after much additional consideration, long after the shutter snaps. It’s not that one shouldn’t strive to get things as perfect as possible in the moment. In fact, there is overwhelming evidence that many photographers do exactly that, nearly all the time.

It’s that “nearly”, however, that describes most photos, something which might be converted to “definitely” in the cropping process. In fact, I am starting to feel that the very first thing to be done with a picture in post-production is to just start paring away, only stopping when the center of the idea has been reached. It’s gut-wrenching, since we usually fall in love with our pictures at first sight (and in their first versions). But even if God decided to make one of us, say Cartier-Bresson, the messenger of his divine eye, he certainly didn’t make that trait as common as, say, green eyes or freckles. For most of us, most of the time, we need to eliminate everything that diverts the eye anywhere but where the main message is. As an example, the hammock image above is the result of cutting away nearly 2/3 of the original photograph.

There are a few times when an image comes full-born out of the camera, all muscle and no fat. However, in the digital age, re-thinking one’s realization of a concept is easier than it’s ever been, and there is no downside to doing so. If there is a narrative ground-zero to your photo, don’t worry. The center will hold.

THE REVISION DRAFT

Reducing is remixing: this Tanglewood rehearsal photo was at least 2/3rds bigger in the original, but a severe crop highlights a relationship between these players that the bigger image buried.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

HERE’S A SENTENCE YOU’RE NOT GOING TO HEAR ANYWHERE ELSE THIS WEEK: Being a club DJ can actually give you a fresh viewpoint on your photography.

I’ll let that sink in.

I know what you you’re thinkin’: did he drink six shots or only five? But I’m kind of sober, and rather serious. In a club setting, the mix is often more important than the song, or, more correctly, it allows the song to have an infinite number of alternative lives, depending on what you do with the turntables. Record companies recognized this in the heyday of disco, remixing hit tracks for more thump and bump, longer edits, brass overdubs, etc. As time went on, DJs interspersed their own random elements in the moment to create their own signature blends.

So what does this have to do with photography? Pretty much everything. In the digital era, post-production software is nearly half of some shooters’ workflow. So much emphasis is placed on what you can fix after the shutter is clicked that, for many, actually planning and taking the picture is the least important part of the process. Let’s lay aside the fact that I personally believe that this can get out of hand…..the point is, by allowing yourself the flexibility to revisit and remix a photo many times over its lifetime means you are not limiting yourself to one interpretation of what you originally created.

However, don’t keep merely to a reprocessing of the exposure or tone elements in the picture, that is, boosting color, adding filters, converting to monochrome. Think of compositional space as a remix element as well. Did you need all the real estate taken up in the original picture? Would that landscape shot work more effectively in portrait or square format? Did you originally include information in the frame that just adds clutter, sending your viewer’s eye wandering around aimlessly? In short, does your first reading of the “idea” of the picture still seem valid?

See the “after” picture at the top of the page and its “before” equivalent to the left. Did the picture gain or lose from the changes?

Another musical musing: George Gershwin personally played Rhapsody In Blue like a snappy jazz piece, not the stately symphonic standard that’s re-created by most modern performers. Does one rendition sound better or worse? Who knows? Who cares? What matters is that the process reveals different traits within the core music with every new mix. Your photographs will benefit in the same way. Just trust yourself to tinker.

GO OUT AND COME BACK IN AGAIN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SEPARATING ONE’S IMAGES INTO “HIT” AND “MISS” PILES is always painful, since it’s kind of like telling some of your kids that they will be power hitters in Little League while their siblings should take up…well, macrame. But self-editing, over time, is nearly as important as shooting, and the mindfulness of asking “what was I thinking” is the useful corollary to “what do I want to do next?” That don’t make it smart any less, but at least you understand the pain.

Usually I hurl photos into the “miss” box for purely technical reasons, which means that I should have known what to do and just blew it upon execution. I’m more exacting nowadays, because present-era camera make it tougher to absolutely boot a shot, although I have striven to stay ahead of the curve and make lousy pictures even in the face of rapidly advancing technology. People who think they’ve idiot-proofed their gear have never met this idiot, I boast. It’s a point of pride.

Occasionally, though, you review a shot that was okay exposure-wise, but completely got the narrative wrong. Sometimes you can recompose the shot and redress this problem, and sometimes you’re just sealed out of the airlock with no oxygen. That’s the breaks. In the original image at the top of this page is a candid of a little girl next to a horse that I thought would be charming. Cute kid, nice horsie, you get the picture. Problem is, I never really captured her essence in any of the photos I shot (trust me) and I framed so tight that I was only showing the horse’s body. First verdict on this one: thanks for playing our game, sorry to see you go, here are some lovely parting gifts.

However, as a rainy day project, the photo suddenly presented a different way for me to go. It wasn’t that I had shown too little of the horse; it was that I had shown too much of both the horse and the child. The central part of the image, taken by itself, had a narrative power that the larger frame lacked. To crop so that just a part of the girl’s small arm connected with the strong, muscular torso of the horse magnified his power by contrasting it with her fragility. I wasn’t losing the horse’s face, since it hadn’t been in the original, and losing the girl’s face actually improved the impact of the image by reducing her to an abstraction, to a symbol of innocence, gentleness, but above all, contact. We could deduce that the horse and the girl were friends. We didn’t need to see it reflected in their features.

Sometimes an image we are ready to reject is hiding a more concentrated fragment that saves the entire thing, if we are unafraid to pare away what we once saw as “essential”. It’s the go-out-and-come-back-in-again school of thought. It’s at least a seeing exercise, and you gotta flex them eye and brain muscles at every opportunity.

A BIG BOX OF LONELY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY CAN GO TWO WAYS ON CONTEXT. It can either seek out surroundings which comment organically on subjects (a lone customer at a largely empty bar, for example) or it can, through composition or editing, artificially create that context (five people in an elevator becomes just two of those people, their locked hands taking up the entire frame). Sometimes, images aren’t about what we see but what we can make someone else seem to see.

Creating your own context isn’t really “cheating” (are we really still using that word?), because you’re not creating a new fact in the photograph, so much as you are slapping a big neon arrow onto said fact and saying, “hey look over here.” Of course, re-contextualizing a shot can lead to deliberate mis-representation of reality in the wrong hands (see propaganda, use of), but, assuming we’re re-directing a viewer’s attention for purely aesthetic reasons (using our powers for good), it can make a single photo speak in vastly different ways depending on where you snip or pare.

In the above situation, I was shooting through the storefront window of a combined art studio and wine bar (yes, I hang with those kind of people), and, given that the neighborhood I was in regularly packed folks in on “gallery hop” nights, the place was pretty jammed. The original full frame showed everything you see here, but also the connecting corridor between the studio and the wine bar which was, although still crowded, a lot less claustrophobic than this edited frame suggests.

And that’s really the point. Urban “hangs” that are so over-attended can give me the feeling of being jammed into a phone booth, like I’m part of some kind of desperately lonely lemming family reunion, so I decided to make that crushed sensation the context of the picture. Cropping down to a square frame improved the balance of the photograph but it also made these people look a little trapped, although oddly indifferent to their condition. The street reflections from the front plane of glass also add to the “boxed in” sensation. It’s a quick way to transform a snap into some kind of commentary, and you can either accept my choice or pass it by. That’s why doing this is fun.

Urban life presents a challenging series of social arrangements, and context in photographs can force a conversation on how that affects us.

MINIMUM SHOW, MAXIMUM SEE

There are only two design elements in this image. Does it really need any more? 1/160 sec., f/4, ISO 100, 24mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LOOK AT THE EARLIEST PHOTOGRAPHIC WORK OF NEARLY ANYONE and you will see a general attempt to frame up a scene and attempt to show, well, everything within range of the camera. It’s a time when we produce our most inclusive panoramas, our most crowded city scenes, our most enormous circus midways. Our pictures may be stories, but, at first, our stories have a bit of a problem getting to the point. We are so inclusive of raw data that every snap of life at the beach becomes a page out of Where’s Waldo? Thus, the very first real talent young photographers show is the ability to trim all that visual fat and get the maximum see for the minimum show.

Of course, when we are mere puppies, it seems counter-intuitive to say that showing less will actually make us see more. Minimalism doesn’t come easily to us, since we are afraid, at first, that we’re leaving something “important” out. Everyone comes to terms with this eventually if they shoot long enough, but we all arrive at the wisdom of it via various journeys. For me, it was my first attempts at still life compositions, which really are the most edited exercises we do. For these kinds of photos, it’s really about knowing what to leave out, or at least when to stop adding. And when a picture works, there is the nagging curiosity as to why….an inquiry which often leads to the conclusion that we used just what we needed, and then stopped.

Sometimes I get a sense of how little I need in a picture while I’m shooting. Many times, though, it comes to me in the editing or cropping process. If I snip something off of a picture and it doesn’t fall apart, I start wondering how much more I can pare away and still say what I’m trying to say. Learning, in recent years, how to compose again for a square frame has really been helpful, too, since it forces you into a pre-determined space limit. You can’t paint any wider than the canvas, if you will. You yourself might find other ways to get to the core balance your story needs. There is no true or single path.

I started the above image in a wide graveyard, then several graves and a tree, then one grave marker and a tree, then just the marker, and finally a portion of the marker. But in what I wound up with, aren’t all the elements I cut away really present for the viewer mentally anyway?

It’s often said, as a generalization, that painters start with nothing and add until they get the picture, while photographers start with everything and strip information away until they see just what they need. I really see a lot of photography that way. Tell the story with as few elements as you can and walk away. Minimum show for maximum see.

Not nearly so counter-intuitive, after all.

LOST LESSONS

Photography can’t grow as part of an assembly line with social media “likes” as its only measure of quality.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE IMMEDIATE GRATIFICATION OF MODERN PHOTOGRAPHY IS A DOUBLE-EDGED SWORD. On one side of the blade, we have effectively eliminated the time-consuming trial-and-error that frustrated generations of shooters. Pictures come practically at our whim, and the instantaneous ability to correct images in the moment results in a learning curve shortened by years. We can potentially get better and know more faster and faster.

That’s the good part.

On the rustier side of the sword, there is the potential for us to crank out photos so quickly that we take less and less time to evaluate them individually. The subtle changes in quality that are contained in a burst of twenty quick shots are lost to us, along with whatever lessons they may impart. We make a general, slapdash call as to what the so-called “keepers” in a batch are, and rush them into the public arena for instantaneous approval. This sprint toward the highest count of “likes” and “views” usually means that we are putting many pictures out there that are not ready for prime time, simply because, technically, we can.

We have to be our own best photo editors.

Social media offers very little in the way of qualitative feedback on what we’ve done right or wrong with a picture. Only our own objective editorial judgement can truly provide that. But we are abdicating that role in our all too human desire for approval, even though online clicks are not so much “approval” as reflexive twitching. Most of us won’t have the luxury of working for hate-crazed photo editors or presenting our work in truly competitive environments, and that puts the responsibility squarely on us. If we don’t act as our own best critics, taking the time and deliberation necessary to evaluate where we’re growing and where we’re stunted, then who is to blame for our failure as artists? Our pals on Facebook?

One great thing about the film era: it forced us to proceed at a more deliberative pace. We were producing photographs slow enough to allow us to make real judgements about them as they emerged. Now we are more like Lucy and Ethel in the chocolate factory. We strive to stay ahead of the merciless assembly line, rather than see if chocolate 5,556 is actually better, or worse, than 5,557.

If you believe, as I do, that more lessons are learned from the pictures that fail, then you must slow down long enough to make sure those lessons are not lost in a meaningless blur.

Share this:

June 11, 2016 | Categories: Conception, editing, Editorial, Viewpoint | Tags: Commentary, Editing, Social Media | Leave a comment