EXTRACTION

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR SOME, UTTERING THE WORD ABSTRACTION ALOUD is like saying bringing up politics at a family get-together, in that it forces people to take sides, or to account for their taste in front of others. And when you tie that scary word to art, specifically photography, people start to forget about making pictures, and begin wondering “what it all means”, or, worse, what an image is “supposed to be about”. We start making photos like regimented school children, all of us coloring the sun the same yellow and always drawing people with eyes in the same part of their face.

Instead of using the term abstraction to describe the idea of seeing something differently, I prefer the word extraction, as if we are pulling something different out of a subject. And it’s really not that academic. When we abstract/extract something, we are changing the relationship between the object and how we typically view it. Can showing just part of its shape register in our brains differently than viewing the entire thing? If I interpret it in monochrome versus color, can I re-shape the way you look at its positive (light) or negative (dark) space?

In abstracting/extracting, aren’t we really acting like designers, taking the familiar and rendering it unfamiliar to look at how it’s made and how we interact with it? Just as a designer might decide to create a different kind of teapot, can’t we take an existing teapot and change the way it impacts the eye? That’s all extraction is; one more way to shuffle the deck.

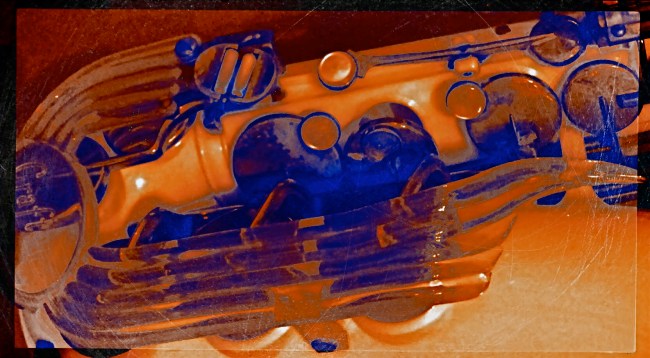

The object at the top of the page, a rare injection-molded plastic saxophone from the 1940’s, had already been “abstracted” by its designer, since we all have a traditional way of visually “knowing” that instrument. That is, it’s supposed to be brass-colored metal, curve in such-and-such a fashion, and feature ornamentation of a set type. Prominently, the designer re-ordered the sax’s features… in plastic, with browns and purples arranged in a fluid, stylized flow of elements. That means, that, as a photographer, I begin with my own set of expectations for the object already substantially challenged. Further, in photographing it, I can rotate the sax, compose it in the frame in an alternate fashion, reassign or intensify its colors, or, as in the small insert(which is a composite of a color negative, a monochrome negative, and a color positive), even change the relationship between surface and shadow.

There is a reason why even the police “abstract” a face into two interpretations, using both head-on and profile views in mug shots. Fact is, when you choose the viewpoint on an object, you change the interpretation of how the eye “learns” it. You extract something fresh from it . That’s the nature of photography, and scary words like “abstract” shouldn’t halt the ongoing conversation about what a picture is…or isn’t.

POCKET MASH-UPS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S TRICKY TRYING TO TRACK THE HISTORIC ORIGINS OF PHOTOMONTAGE, or to even isolate great early practitioners of the technique. Suffice it to say that, ever since the development of the glass negative, people have wondered what it would look like if you stacked one of them on top of the other and printed the result. Opinions vary wildly as to whether the results of such experiments constitute madness or miracle…it’s a taste thing. One thing is clear, however: the mobile age presents easier means than ever before for diving in to the montage pool and creating fast experiments at a fraction of the hassle experienced in film days.

(Now is the part where you decide whether that’s a good thing…..)

One of the top benefits of phone-based cameras is the huge number of highly responsive apps targeted at the tinkerer, the guy who wants to try just one more filter, one more effect, or a grand mash-up of everything together. Unlike the days of lab-based development and printing, digital montages are almost an immediate thrill. Better still, they can be re-imagined and re-done with the same short turnaround time inherent in all digital processes. That means that certain types of shots that would have priced themselves out of many a film shooter’s budget or know-how in Film-World are now just givens in Digital World.

(Now is the part where you decide how you feel about that…..)

If the same tools for experimentation or interpretation are in everyone’s hand, then such effects are no longer judged as wonderful just because they are rare, or novel, but for how well they are employed. In fact, a gimmick like photomontage can quickly become tiresome if over-used or under-inspired. The sample shots in this post are two-image composites processed on an app called Fused, which allows two photos at a time to be overlaid and custom-blended for a variety of contrast and color tweaks. Sometimes the effect can help pictures which are totally dissimilar find some common bond, but, at least for me, about 90% of the blends I try are kinda meh and are sent to the Phantom Zone faster than you can say “well, that didn’t work”. You can’t force the linkage just to be arty (well, of course you can, but..).

Pocket mash-ups are just one more way to untether photography from “reality” (whatever that is), and channel it into a personal form of abstract expression. That means it’s all about you. So what’s not to like?

TAKING OFF THE TRAINING WHEELS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S HARD TO BE ANGRY WITH ANY TREND THAT MAKES PHOTOGRAPHY MORE DEMOCRATIC, or puts cameras into more hands. Getting more voices in the global conversation of image-making is generally a great things. However, it comes with a price, one which may make many people actually give up or stagnate in their growth as photographers.

We may be killing ourselves, or at least our art, with convenience.

Cameras, especially in mobile devices, have exponentially grown in ease (and acuity) of use over the last fifty years, but they are actually teaching people less and less about what, technically, is happening in the making of an image. The nearly intuitive logic of smaller and easier cameras means that many people, while busily snapping away and producing billions of pictures, are being more and more estranged from any real knowledge of how it’s all being done.

This is a vicious circle, since it guarantees that a greater number of us will be more and more dependent upon our cameras to make the bulk of the creative decisions for us, more obliged to accept what the camera decides to give us. In some very real way, we are being shortchanged by never having had to work with a garbage camera. Let me explain that.

Being forced to do creative work with an unyielding or primitive tool puts the responsibility for (and control of) the art back on the artist. Those who began their shooting careers with limited box cameras understand this already. If you start making pictures with a device that is too limited or “dumb” to do your bidding, then you have to devise work-arounds to get results. That means you learn more about what light does. You learn what ideal or adverse conditions look like. You see what failure is, and begin to dissect what didn’t work for a stronger understanding of what may work next time. You learn to ride a bike without training wheels, and thus never need them.

The dark lobby of New York’s Chrysler building: An extremely challenging setting for low-light photography. I screwed this up on a cosmic scale, but I learned a ton. Shooting on automodes, I would have learned precisely…nothing. And the picture still would have stunk.

The above image, taken on manual settings in a less-than-ideal setting, has about a dozen things wrong with it, but the mistakes are all my mistakes, so they retain their instructive power. If something was blown, I know how it can be corrected, since I’m the one who blew it. There is a clear linear learning process that benefits from making bad pictures. And if my camera had done everything itself and the picture still reeked, then I’d be stuck with both failure and ignorance.

Cameras that remove the risk of failure also remove the chance of accidental discovery. If you always get acceptable images, you’re less likely to ask what lies beyond….what, in effect, could be better. You accept mediocrity as a baseline of quality. And editing tools that consist mostly of corrective solutions, from straightening to sharpening, keep you from addressing those errors in the camera, and that, too, robs you of valuable experience.

Convenience, in any art medium, can either abet or prevent excellence. The amount of curiosity and hunger in the individual is the decisive factor in moving from taking to making pictures. For my money, if you’re going to grind out the process of becoming an artist, you can’t rely on equipment that is designed to protect you from yourself.

LEFT, RIGHT, LEFT

Both of the images in this improvised double-exposure were taken within a space of five minutes. Final processing was finished in ten.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN HER BRILLIANT 1979 BEST SELLER DRAWING ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE BRAIN, art teacher Betty Edwards, while obviously addressing the creative process chiefly as it regards graphics, also contributed to a better understanding of the same visualization regimen used by photographers. In its clear explanation of the complementary roles of the brain’s hemispheres in making an image, Ms. Edwards demonstrates that photographs can never be just a matter of chiefly left-brained technique or merely the by-product of unfettered, right-brained fancy.

And that’s important to understand as we grow our approach to our craft over time. It’s ridiculous to imagine that we can make compelling images without a certain degree of left-brained mastery, just as you can’t drive a nail if you don’t know how to hold a hammer. But it’s equally crazy to try to take pictures without the right-brained inspiration that sees the potential in a composition or subject even before the left knows how, technically, it can be achieved. One side problem-solves while the other dreams. One hemisphere is an anchor, a foundation: the other is a helium balloon.

When you develop a plan for your next shoot, selecting the lenses and tools you’ll need, scoping out the best locations, it’s all left brain. But, comes the day of the shoot, your right brain might just fall in love with something that wasn’t in the blueprint, something that just must be dealt with now. Fact is, neither side can hold absolute sway. When you are laboring a long time to get a particular picture, you can almost feel the two hemispheres arguing for control. But all that left-right-left toggling isn’t a bad thing, nor should you expect there to be one clear “winner” in the struggle. The pictures that emerge have to be an agreement, or at least a truce between “how do we do this?” and “why should we do this?”.

I have pictures, such as the one up top here, that I call five-minute wonders, so named because they go very quickly from conception to completion. They are like impulse items in the grocery checkout line. I’ll take some of this, a few of these, and one of those, toss them together in a bowl, and see what happens. Sounds very right-brained, right? However, none of these quickie projects would work if I simply don’t know how to make the camera give me what I want. That’s all left brain. The point is, the two factions must at least have a grudging conversation with each other. Right-brained creativity gets all the chicks and the cool clothes: it’s the flashy rock star of the photo universe, a sexy bad boy who just won’t listen to reason. However, Lefty has to take the wheel occasionally or Righty will crash the sports car and we’ll all die horribly.

It’s romantic to believe that all our great photographs come from blindingly brilliant flashes of pure inspiration. That’s where the lomography movement with its cheap plastic cameras and its “don’t think, shoot” mantra comes from. And impulse certainly plays its part. However, anyone who tells you that amazing images come solely from some bottomless wellspring of the soul is only telling you half the truth. Sometimes you can spend the day playing hooky, and some days you gotta stay inside and do your homework.

Left, right, left….

IT’S ALL WRONG BUT IT’S ALL RIGHT

I decided in the moment to go soft with this nature scene. Maybe I overdid it. Maybe it’s okay. Or not.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE ONLY CONSTANTS OVER THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY has been the flood tide of tutorial materials covering every aspect of exposure, composition, and light. The development of the early science of capturing images in the 19th century was accompanied, from the first, by a staggering load of “how to” literature, as the practice moved quickly from the tinkering of rich hobbyists to one of the most democratic of all the art forms. In little more than a generation, photography went from a wizard’s trick to a series of simple steps that nearly anyone could be taught.

In calling these pages the “photoshooter’s journey from taking to making”, we have made, with The Normal Eye, a deliberate choice not to add to the mountainous load of technical instruction that continues to be available in a variety of classroom settings, but to emphasize why we make photographs. This is not to say that we don’t refer to the so-called “rules” that govern the basics of creating an image, but that we believe the motives, the visions behind our attempts are even more important than just checking items off a list of techniques in the name of doing something “right”. There are many technically adept pictures which fail to engage on an emotional or aesthetic level, so the mission of The Normal Eye, then, is to start discussions on the “other stuff”, those indefinable things that make a picture “work” for our hearts and minds.

The idea of what a “good picture” is, has, over time, drifted far and wide, from photographs that mimic reality, to those that distort and fracture it, to images that are both a comment and a comment on a comment. It’s like any other long-term relationship: complicated. Like everyone else, I occasionally produce what I call a “fence-sitter” photo like the one above, which I can both excuse and condemn at the same time.

In raw technical terms, I have obviously violated a key rule with the abject softness of the image…..unless……unless it can be said to work within the context of the other things I was seeking in this subject. I was trying to stretch the envelope on how soft I could make the mix of dark foliage and hazy water in the scene, and, while I may have gone a bit too far, I still like some of what that near-blur contributes to the saturated color and lower exposure, the overall quiet tone I was trying for. Still, as of this moment, I’m still not sure whether this one is a hit or a miss. It might be on the way to something, but I just can’t say.

But that’s what the journey is about. It can’t be confined to mere technical criteria. You have to make the picture speak in your own language.

THE EVENTUALITY OF ABOUT

“Something’s going to happen. Something….wonderful!” —Astronaut David Bowman, “2010: The Year We Make Contact”

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY’S FIRST FUNCTION WAS AS A RECORDING MEDIUM, as a way to arrest time in its flight, to freeze select seconds of it. As evidence. As reference points. We were here. This happened. Soon, however, the natural expansion that art demands generated images of the things that happened before our direct experience. Ruins. Monuments. Cathedrals. Finally, the photograph began to speculate forwards. To anticipate, even guess, about what might be about to happen. That is the photography of the potential, the imminent. It’s rather ghostly. Indefinite. And all in the eyes of the creator and the beholder.

Is something about to happen? Does this place, this kind of light, truly portend something? Can a picture said to be ripe with the possibility of emerging events? I think they can, but these bits of pre-history are harder to sense than those we capture in the mere recording or retrieval functions of photography. In this case, we are not just witnesses or detectives, but seers. Of course, we may be wrong. Something may not happen as we seem to see it at present. History may not be made here. Perhaps no one will ever say or do anything extraordinary on this spot. The image of the possibility, then, becomes a kind of creative fiction, a pictorial what-if. And that places photos in the same arena as sci-fi, mysticism, poetry. If other arts can paint worlds that might be, why can’t a picture?

I don’t know why the meeting room shown here, which was being prepared for a conference later in the day, struck me. It might have been the somber color scheme, or the subdued light. It may have been the grand emptiness of it all; a room designed to be packed with people, sitting there, waiting for them to animate it. I just know that it was enough to slow my trek through a resort hotel long enough to try to show that potential. For what? A moment of high corporate drama? The end of someone’s career, the launch pad for a bold new idea? The meeting that might redraw the map of human destiny? Or nothing?

Ah, but what actually happens after the photo is taken is mere reality, and never to be matched or compared with the strong sense of eventuality that can linger in an atmosphere before something occurs. These kind of images are not, after all, witnesses to anything, but visions of the possible. And that is the essence of photography, where even a medium invented to record reality can ofttimes transcend it.

TINY TOWNS AND BIG DREAMS

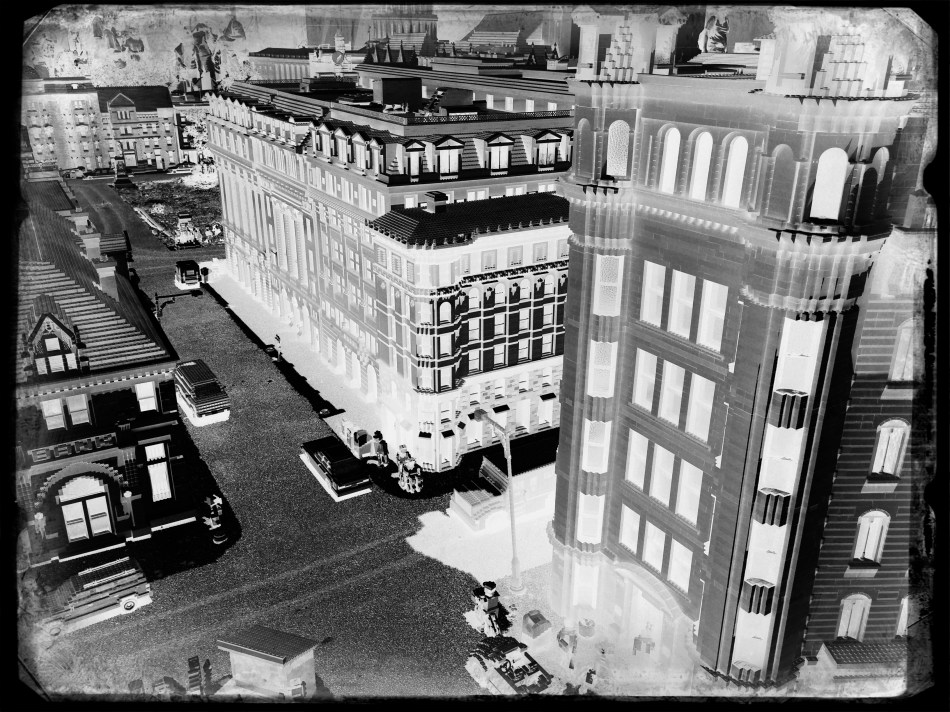

Eclectic Light Orchestra: Shooting the Musical Instrument Museum’s amazing orchestral diorama to scale.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE ART OF MESSING ABOUT WITH THE MIND’S CONCEPT OF SIZE, making the small look large, has been part of photography since the beginning, whether it’s been crafting the starship Enterprise at 1/25 scale for primitive special effects or making Lilliputian mockups of Roman warships for a sea battle in Ben-Hur. Making miniatures a convincing stand-in for full-size has been a constant source for amazing images.

Oddly, there has also been a growing fascination, in recent years, with using new processes to make full-sized reality appear toy-like, as if Grand Central Station were just a saltine box full of HO-scale boxcars. Seems no one thinks things are as they should be.

This turnabout trend fascinates me, as people use tilt-shift and selective-focus lenses, along with other optics, to selectively blur and over-saturate real objects taken at medium or long distances to specifically create the illusion that you’re viewing a tabletop model. Entire optical product lines, such as the Lensbaby family of effects lenses, have been built around this idea, as have endless phone apps and Photoshop variants. We like the big to look small just as much as we like the teeny to look mighty. Go figure.

And who can resist playing on both sides of the street?

The image at the top is the usual fun fakery, with my tiny-is-full-size take on the marvelous diorama made for the Musical Instrument Museum (the crown jewel of Phoenix, Arizona), which reproduces a complete symphony orchestra in miniature. This amazing illusion was created using a spectacular photo system that creates a 360-degree scan of each full-sized player, maps every item of his features, costume, and instrument, then converts that scan to a 3-d printed, doll-sized version of every member of the symphony. To read about this awesome process, go here.

As for making regular reality look like Tiny Towns, we offer the image at the left, taken by photographer Jefz Lim as part of his online tutorial on the creation of the “model” effect. We are in the age of ultimate irony when we deliberately try to palm off the real as the fake. The “how” of this kind of image-making is basic focus-pocus. The “why” is a little harder to put your finger on.

Size does matter. Ah, but what size matters the most…..that’s your call.

TERMS OF ENGAGEMENT

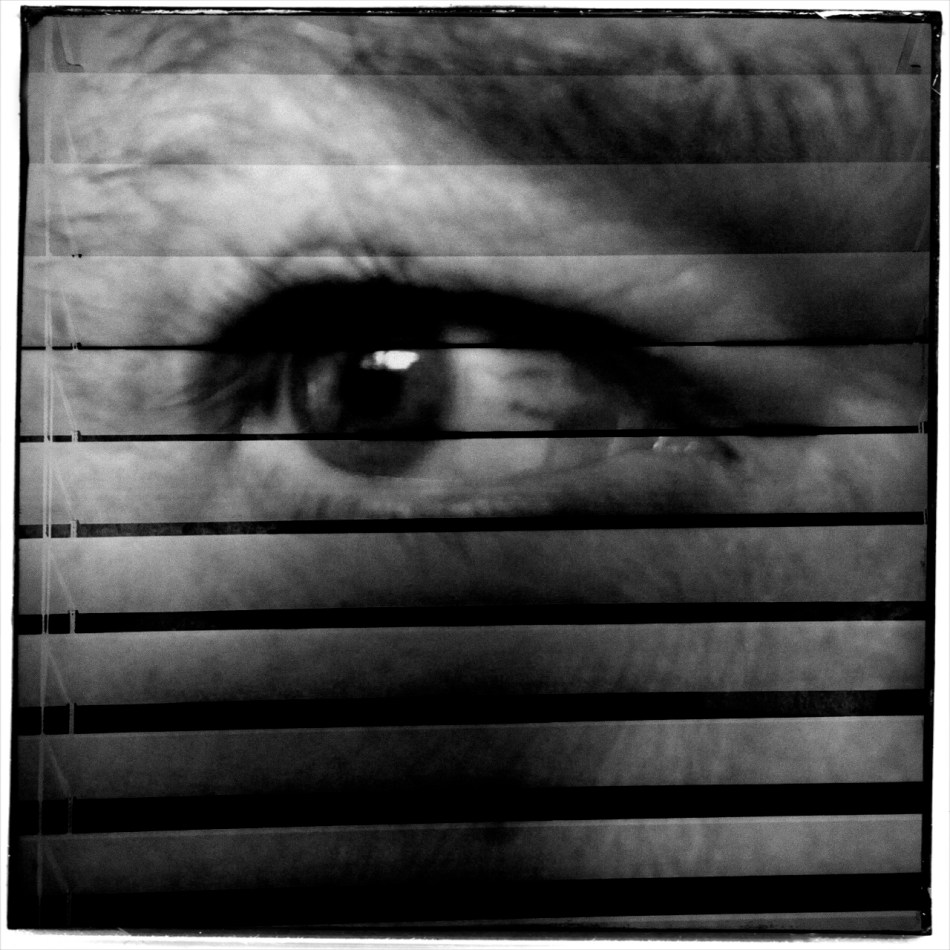

A very soft color cel phone original becomes a stark “box”, suggested solely by a pattern of black and white bands.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ABSTRACT COMPOSITIONS AREN’T MERELY A DIFFERENT WAY OF PHOTOGRAPHING A SUBJECT: they are, in many cases, the subject itself. Arrangements of shape, shadow and contrast can be powerful enough to carry the weight of a picture all by themselves, or at least be an abbreviated, less-is-more way of suggesting objects or people. And in terms of pure impact, it’s no surprise that photographers who, just a generation ago, might have worked exclusively in color, are making a bold return to black and white. For abstract compositions, it’s often the difference between a whisper and a shout.

I find it interesting that the medium of comics, which has long been defined by its bold, even brutal use of color, is also experiencing a black & white resurgence in recent years, with such masters as Frank Miller (Batman: The Dark Knight Returns) rendering amazing stuff in the most starkly monochromatic terms. Likewise, the army of apps in mobile photography has reminded young shooters of the immediacy, the power of monochrome, allowing them to simulate the grain and grit of classic b&w films from Tri-X to Kodalith, even as a post-production tweak of a color original.

You know in the moment whether you’ve captured a conventional subject that sells the image, or whether some arrangement of forms suggestive of that subject is enough. In the above shot, reducing the mild color tonal patterns of a color original to bare-boned, hard blacks and loud whites creates the feel of a shaded door frame..a solid, dimensional space. The box-like enclosure that envelops the door is all there, but implied, rather than shown. As a color shot, the image is too quiet, too…gentle. In monochrome, it’s harder, but it also communicates faster, without being slowed down by the prettiness of the browns and golds that dominated the initial shot.

There are two ways to perfect a composition; building it up in layers from nothing into a “just-enough” something, or stripping out excess in a crowded mash-up of elements until you arrive at a place where you can’t trim any further without losing the essence of the picture. Black and white isn’t just the absence of color: it’s a deliberate choice, the selection of a specific tool for a specific impact.

FACE TIME

The resurrected World Trade Center, as seen at eye (rather than “craning neck”) level. 1/125 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 24mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I AM OFTEN ASKED WHY ARCHITECTURE FIGURES SO STRONGLY in my photography, and I can only really put part of my answer into words. That’s what the pictures are for. I imagine that the question itself is an expression of a kind of disappointment that my work doesn’t focus as much on faces, as if the best kind of pictures are “people pictures”, with every other imaging category trailing far behind. But I reject that notion, and contend that, in studying buildings, I am also studying the people who make them.

Buildings can be read just as easily as a smile or a frown. Some of them are grimaces. Some of them are grins. Some of them show weary resignation, despair, joy. Architecture is, after all, the work of the human hand and heart, a creative interpretation of space. To make a statement? To answer a need? The furrowed brows of older towers gives way to the sunny snicker of newborn skyscrapers. And all of it is readable.

In photography, we are revealing a story, a viewpoint, or an origin in everything we point at. Some buildings, as in the case of the first newly rebuilt World Trade Center (seen above), are so famous that it’s a struggle to see any new stories in them, as the most familiar narratives blot the others out of view. Others spend their entire lives in obscurity, so any image of them is a surprise. And always, there are the background issues. Who made it? What was meant for it, or by it? What world gave birth to this idea, these designs, those aims?

Photography is about both revelation and concealment. Buildings, as one of the only things we leave behind to mark our having passed this way, are testaments. Read their faces. No less than a birthday snapshot, theirs is a human interest story.

WHEN TOY BECOMES TOOL

It’s possible to get a truly steady wide-angle image from iPhone’s in-camera pano tool. But it takes some real work, and not a little luck.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY TECHNICAL ADVANCEMENT IN THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY has been a double-edge sword, creating either novel gimmickry or a wider array of serious technique, depending on who’s playing the game. The most popular tools available to the widest number of users, from fisheye lenses to phone app filters, illustrate this point again and again. Some people pick up these new features, play with them for a bit, then abandon them forever, while others use them as a way to expand their approach to visualizing an image.

I have written here before about iPhone’s in-camera panoramic tool, which I expect was originally included as a family-friendly option, perfect for making sure that everyone on the Little League team or the family reunion could be captured in one frame, the app instantly stitching a series of narrower photos taken in real time during a left-to-right pan. And, while it can certainly serve in that snapshot-y task, it creates its own set of technical problems. Nonetheless, I have become convinced, over the last few years, that it can lend additional ooomph to serious image making if (a) one is extremely selective in what is shot with it, and (b) the built-in shortcomings of the app can be worked around in the moment.

As with any other technical toy/tool, the results depend on how well you understand the strengths and weaknesses of iPhone’s pano app and plan your shots. Since you pan by pivoting your body (as if it’s the hub of a wheel), you can’t maintain the same distance from your entire subject as you move the camera left to right. That means that the center of that pivot, or what’s dead ahead of you, will tend to distort outward, like the center of a fisheye shot. Depending on what’s at the middle of your shot and how far you are from it, this can give you some unwanted funhouse results.

Also, in what is odd for a tool that’s designed to take pictures of lots of people, using the iPhone pano app to shoot a live, moving crowd is truly hit-or-miss. If a person moves through your picture as you are panning in the same space they occupy, they may be recorded as a slice or a piece of themselves, being caught partly in some of the picture’s vertical “tiles” but absent from the ones directly adjacent to it, causing them to register as a disembodied leg or a slivered torso floating in the air (see left).

In the shot at the top of this page, I was lucky that the street magician at left was standing still during the time I panned across him (once I’ve recorded his part of the frame, he can do what he likes, since the lens no longer “sees” that part of the picture). Likewise the crowd, enthralled by his performance, was remaining pretty static as I completed the pan across their part of the frame. The result has all the story-telling power of an ultra-wide shot, and, because of the composition, actually uses the fisheye-ish bulge to make the segmented pavement appear to be radiating outward from the performer.

And of course there is the subject itself, which has to benefit from all that left-right arrangement of information if you want to avoid just taking the picture for the sake of the effect alone. And there we have the balance between toy and tool that every photographer hopes to strike. Toys get cast aside once boredom sets in. Tools stay around and add to your work in very real ways.

POST #500: ON THE ROAD TO CHERRY GARCIA

By MICHAEL PERKINS

VISITORS TO THE FACTORY HEADQUARTERS OF BEN & JERRY’S ICE CREAM in Stowe, Vermont, upon completing the standard tour of the works, are encouraged to climb a small hill out back of the building to view the company’s Dead Flavor’s Graveyard, an actual cemetery, complete with elegantly epitaphed tombstones and dedicated to such failed B&J varietals as Turtle Soup, Fossil Fuel, White Russian and Sweet Potato Pie. It’s a humorous way to point out that, even for talented startups, there’s no such thing as a direct shot up the mountain of fame. We duck. We detour. We change direction. It’s a process, not a product.

Photography is, in this way (and in no other way that I can think of) much like ice cream.

As we clear the 500 mark on posts for The Normal Eye, I want to (a) profoundly thank all those who have joined us on the journey, and (b) restate that, as our sub-head reads, it really is about a journey, rather than a destination. This small-town newspaper began because I had met so many people over the years who had become suspicious of their camera’s true intentions. Sure, they admitted, the automodes do pretty great on many pictures, but what if I actually want some say in the process? Can I be an active agent in the making of my own pictures?

Now, these weren’t people who wanted to purchase $10,000 worth of gear, sell their houses, abandon their children, and become photo gypsies for NatGeo. These were simply people whose photographic curiosity had finally got the better of them. What would happen, they asked, if I were to, all by myself, make one little extra choice, independent of the camera’s superbrain, before the shutter snapped? And what if I made two? Or three? Other questions followed. What is seeing? How do you learn to value your own vision? And what tasks from the era of film still apply as solid principles in the digital age?

The Normal Eye has spent the last four years trying to ask those questions, not from a top-down, “here is how to do it” approach, since so many of these solutions must be privately arrived at. This is not, and will never be, a technical tutorial. I reflect on what thoughts went into a particular problem, and how I personally decided to try to solve it. The results, as are all my words, are up for debate.

It’s humbling to remember that, in photography, there is always more than one path to paradise. And when I find myself being crushed under the weight of my own Dead Flavor Graveyard, I take heart in those moments when your feedback has made a difference in my motivations, or methods, or both. Recently, I received what I still cherish as one of the best comments over the entire run, with one gentleman proclaiming:

I’m not a fan of words, but the ones in this article are in a tolerable sequence.

Hey, that’s enough to hold me for another 500, and I hope you’ll be along for the ride.

WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS’ FIRST USES OF FILTERS WERE AS THE TWIST-ON TOOLS designed to magnify, nullify or modify color or light at the front end of a lens. In the digital era, filtration is more frequently added after the shutter clicks, via apps or other post-production toys. You make your own choice of whether to add these optical layers as a forethought or a post-script. However, one of the simplest and oldest of filtering options costs no money and little time, and yet continues to shape many a great image: a window.

No panes are optically identical, just as the lighting conditions that affect them are likewise completely unique, so the way that they shape pictures are constantly in flux, as are the results. It’s no surprise that the shoot-from-the-hip urban photographers who favor spontaneity over all pay little attention to whether shooting through a window “ruins” or “spoils” an image. Taking an ad-lib approach to all photographic technique, the hip shooters see the reflections and reflections of glass as just another random shaper of the work, and thus as welcome as uneven exposure, cameras that leak light, or cross-processed film: another welcome accidental that might produce something great.

Windows can soften, darken or recolor a scene, rendering something that might have been too strait-laced a little more informal. This quality alone isn’t enough to salvage a truly bad shot, but might add a little needed edge to it. The images seen here were both “what the hell” reactions to being imprisoned on tour buses, the kinds that don’t stop, don’t download their passengers for photo or bathroom breaks, or which are booked because I am tired of walking in the rain.

In the case of the tour driver’s cab, his inside command center and personal view are really part of the story, and may outrank what he’s really viewing. In the side-window shot of an early morning in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the tinted glass acted much in the way of a polarizing filter, making the resulting photo much moodier than raw reality would have been.

Which is the point of the exercise. When you feel yourself blocked from taking the picture you thought you wanted, try taking it the way you don’t think you want to. Or just think less.

Wait, what did he just say?

SEE DICK THINK.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FORGET BLOWN EXPOSURES, SHAKY SNAPSHOTS, AND FLASH-SATURATED BLIZZARDS. The hardest thing to avoid in the taking of a picture is winding up with a picture full of other people taking a picture. Hey, democracy in art, power to the people, give every man a voice, yada yada. But how has it become so nearly impossible to keep other photographers from leaning in, crossing through, camping out or just plain clogging up every composition you attempt?

And is this really what I’m irritated about?

Maybe it’s that we can all take so many pictures without hesitation, or, in many cases, without forethought or planning, that the exercise seems to have lost some of its allure as a deliberate act of feeling/thinking/conceiving. Or as T.S. Elliot said, it’s not sad that we die, but that we die so dreamlessly. It’s enough to make you seek out things that, as a photographer, will actually force you to slow down, consider, contemplate.

And one solution may lie in the depiction of other people who are, in fact, taking their time, creating slowly, measuring out their enjoyment in spoonfuls rather than buckets. I was recently struck by this in a visit to the beautiful Brooklyn Botanical Gardens on a slow weekday muted by overcast. There were only a few dozen people in the entire place, but a significant number of those on hand were painters and sketch artists. Suddenly I had before me wonderful examples of a process which demanded that things go slowly, that required the gradual evolution of an idea. An anti-snapshot, if you will. And that in turn slowed me down, and helped me again make that transition from taking pictures to making them.

Picturing the act of thought, the deep, layered adding and subtracting of conceptual consequence, is one of the most rewarding things in street photography. Seeing someone hatch an idea, rather than smash it open like a monkey with a cocoanut does more than lower the blood pressure. It is a refresher course in how to restore your own gradual creativity.

PUT ‘ER IN REVERSE

A glass elevator at a shopping mall, converted to a negative, then a fake Technicolor filter in a matters of seconds, via the phone app Negative Me.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE MANY WAYS TO FORCE YOUR AUDIENCE TO SEE THINGS ANEW, to strip away their familiar contexts as everyday objects and create a completely different visual effect. The first, and most obvious form of abstraction we all learned in our cradle, that of rendering a subject in black and white. Some early photographers spent so many years in monochrome, in fact, that they actually regarded early color with suspicion, as is it was somehow less real. The moral of the story is: the photograph demonstrates the world that you dictate, shown strictly on your own terms.

Abstraction also comes about with the use of lenses that distort distances or dimensions, with re-assignment of color (green radishes, anyone?), and by compositions that extract subjects from their natural surroundings. Isolate one gear from a machine and it becomes a different object. Magnify it, light it differently, or show just a small portion of it, and you are taking it beyond its original purpose, and into abstraction. Your viewer is then free to re-interpret how he sees, or thinks, about that thing.

One swift gift of the post-digital world that I find interesting is the ability, through apps, to render a negative of any image with a click or swipe, then modifying it with the same color filters that you might apply to a positive photo. This affords an incredible amount of trial-and-error in a remarkably short space of time, and better yet, you’re out in the world rather than in the lab. Of course, negatives have always been manipulated, often to spectacular effect, but always after it was too late to re-take the original picture. Adjustments could be made, certainly, but the subject matter, by that time, was long gone, and that is half the game.

Reversing the color values in a photograph is no mere novelty. Sometimes a shadow value can create a stunning design when “promoted” to a lead value with a strong color. Sometimes the original range of contrast in the negative can be made more dramatic. And, occasionally, the reversal process renders some translucent or shiny surfaces with an x-ray or ghostly quality. And, of course, as with any effect, it can just register as a stupid novelty. Hey, it’s a gimmick, not a guarantee.

“Going negative”, as they say in the political world, is now an instantaneous process, allowing you the most flexibility for re-takes and multiple “mixes” as you combine the neg with everything from toy camera effects to simulated Technicolor. And while purists might rage that we are draining the medium of its mystery, I respectfully submit that photographers have always opted for fixes that they can make while they are in the field. And now, if you don’t like the direction you’re driving, you can put ‘er in reverse, and go down a different road.

ABSOLUTES

This image isn’t “about” anything except what it suggests as pure light and shape. But that’s enough. 1/250 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE POPULARLY-HELD VIEW OF THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY makes the claim that, just as video killed the radio star, camera killed the canvas. This creaky old story generally floats the idea that painters, unable to compete with the impeccable recording machinery of the shutter, collectively abandoned realistic treatment of subjects and plunged the world into abstraction. It’s a great fairy tale, but a fairy tale nonetheless.

There just is no way that artists can be regimented into uniformly making the same sharp left turn at the same tick of the clock, and the idea of every dauber on the planet getting the same memo that read, alright guys, time to cede all realism to those camera jerks, after which they all started painting women with both eyes on the same side of their nose. As Theo Kojak used to say, “nevva happennnned…”

History is a little more, er, complex. Photography did indeed diddle about for decades trying to get its literal basics right, from better lenses to faster film to various schemes for lighting and effects. But it wasn’t really that long before shooters realized that their medium could both record and interpret reality, that there was, in fact, no such simple thing as “real” in the first place. Once we got hip to the fact that the camera was both truth teller and fantasy machine, photographers entered just as many quirky doors as did our painterly brothers, from dadaism to abstraction, surrealism to minimalism. And we evolved from amateurs gathering the family on the front lawn to dreamers without limit.

I love literal storytelling when a situation dictates that approach, but I also love pure, absolute arrangements of shape and light that have no story whatever to tell. As wonderful as a literal capture of subjects can be, I never shy away from making an image just because I can’t readily verbalize what it’s “about”. All of us have photos that say something to us, and, sometimes, that has to be enough. We aren’t always one thing or the other. Art can show absolutes, but it can’t be one.

There is always one more question to ask, one more stone to turn.

THE SINGLE BULLET THEORY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

Okay, Wang, I think that’s enough pictures of the parking lot. —Rodney Dangerfield, Caddyshack

IF YOU WERE TO EXPRESS TODAY’S PHOTOGRAPHIC FREEDOM IN TERMS OF FIREPOWER, it would be fair to say that many of us have come to shoot in a somewhat scatter-shot fashion, like someone sweeping a machine gun. Indeed, digital allows us to overshoot everything to such a degree that doing so becomes our default action, because why would you take one picture of your child digging into birthday cake when fifty will do just as well?

Some over-shooting is really what pro photogs used to call “coverage” and is actually beneficial for particularly hard subjects. Awe-inspiring sunsets. A stag at bay. The fiery burst from a Hawaiian volcano. Such subjects actually warrant a just-one-more approach to make sure you’ve thought through every possible take on something that can be interpreted in a variety of ways, or which may be vanishing presently. But that’s a lot different from cranking off four dozen clicks of the visitor’s center at Wally World.

Shooting better isn’t always assured by merely shooting more. Instead of the machine gun technique, we might actually improve our eye, as well as our ability to strategize a shot, by limiting how many total tries we make at capturing an image. My point is that there are different “budgets” for different subject matter, and that blowing out tons of takes is not a guarantee that Ze Beeg Keeper is lurking there somewhere in the herd.

So put aside the photographic spray-down technique from time to time and opt for the single bullet theory. For you film veterans, this actually should be easy, since you remember what it was like to have to budget a finite number of frames, depending on how many rolls you packed in. Try giving yourself five frames max to capture something you care about, then three, then one. Then go an entire day taking a single crack at things and evaluate the results.

If you’ve ever spent the entire day with a single focal length lens, or fought severe time constraints, or shot only on manual, you’re already accustomed to taking a beat, getting your thinking right, and then shooting. That’s all single-take photography is; an exercise in deliberation, or in mindfulness, if you dig guru-speak. Try it on your own stuff, and, better yet, use the web to view the work of others doing the same thing. Seek out subjects that offer limited access. Shoot before your walk light goes on at an intersection. Frame out a window. Pretend an impatient car-full of relatives is waiting for you with murder in their hearts. Part of the evolution of our photography is learning how to do more with less.

That’s not only convenient, in terms of editing. It’s the very soul of artistry.

THE THIRD WAVE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’VE BEEN DRENCHED IN A VIRTUAL TIDAL WAVE over the last few days, visiting one of those torrential storms of discontent that can only exist on the internet, churning furiously, forever, no resolution, no winner. I don’t know when it began; I only know that, six months, a year, or a decade from now, if I return for more, the storm will still be raging, the two forces inexhaustible in their contempt for each other.

In one corner will be the photographers who believe that equipment has no determination in whether you make great pictures. In the other corner will be those who believe that you absolutely need good gear to make good images. The invective hurled by each combatant at the other is more virulent than venom, more everlasting than a family feud, more primal than the struggle between good and evil.

If you dig bloodsport, enter the maelstrom at the shallow end by Googling phrases like “Leicas are not the greatest cameras” or “your camera doesn’t matter” and then jump behind a barricade. Do more provocative searches like “hipsters are ruining photography” or “don’t think, just shoot” at your peril.

Waikiki Beach, 2009. I’d love to tell you what I did right with this picture, but I honestly don’t remember. 1/500 sec., f/5.6, ISO 140, 60mm.

As with many other truth quests in photography, this one shows strong evidence for both of the waves in the surge. Certainly a great piece of equipment cannot confer its greatness upon you, or your work. And, from the other side, sometimes a camera’s limitations places limits, or at least austere challenges, upon even superbly talented people. And, so, to my mind, there is a third, more consistently true wave: sometimes there is a magic that makes it to the final frame that is mysterious, in that you don’t know how much of the picture you took, how much the camera took, or just how ready the cosmos was to serve that picture up to you. See image above, which I can no longer take either credit or blame for.

Yeah, that’s a little Zen high priest in tone, but look over your own work, especially things you did five or more years ago, where it’s now difficult to recall the exact circumstances of the success of a given image. Pull out the pictures that could be correctly captioned “I don’t know how I got that shot”, “I guess I just went for broke”, or “don’t ask me why that worked out..” There will be more pictures that fall between the extremes, that are neither “thank God I had my cool camera” nor “thank God I was able to make that image despite my limited gear.” That middle ground is the place where miracles thrive, or die on the vine. That strange intersection of truth , far beyond the lands of my-side/your-side heat, is where lies the real light.

YA BIG SOFTIE

These uber-cupcakes didn’t look nearly seductive enough in reality, so I added a gauzy layer in SoftFocus and a faux Technicolor filter in AltPhoto.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST FREEING THINGS about digital photography, especially in the celphone era, has been the artificial synthesis, through aftermarket apps, of processes that used to require lengthy and intricate manipulation. Much has been written about various apps’ ability to render the look of a bygone film stock, an antique lens, or a retro effect with just a click or swipe. The resulting savings in time (and technical trial and error) is obvious in its benefit, as more people shoot more kinds of images in which the shooter’s vision can be realized faster, perhaps even more precisely, than in the days of analog darkrooms.

Okay, now that the sound of traditionalists’ heads exploding subsides, on to the next heresy:

The creation of the so-called Orton technique by Michael Orton in the 1980’s was a great refinement in effects photography. The idea was simple: take two images of a subject that are identical in every spec except focus, then blend them in processing to create a composite that retains rich detail (from the sharp image) and a gauzy, fairy-tale glow (from the softer one). The result, nicknamed the “slide sandwich”, was easy to achieve, even for darkroom under-achievers. The most exacting part was using a tripod to guarantee the stability of the source images. Looked nice, felt nice.

Early on in digital, editing suites like Photomatix, designed to create HDR chiefly, also featured an option called Exposure Fusion, which allowed you to upload the source images, then tweak sliders for the best blend of sharp/no sharp. And finally, here come the soft-focus phone apps like Adobe Photoshop Express, Cool Face Beauty, Camera Keys, and yes, Soft Focus, allowing you to take just one normally focused shot and add degrees of softness to it.

Caveat emptor footnote: not all these apps (and there are many more not cited here) allow you to begin at a “zero effect” start point, that is, from no softening to some softening. They start soft and get softer. Also, most allow basic tweaks like brightening and saturation, but that’s about it. If you want to add contrast or something sexier, you may have to head back to the PC.

The important thing about softening apps are: (1) they save time and trouble in the taking of the source image, of which you only need one (which can be handheld now), and (2) they don’t so much as soften the master image as layer a gauzy glow over top of it.You either like this or you don’t, so, as Smokey says, you better shop around. Gee-whiz factor aside, the old rule for gimmicks still applies: tools are only tools if you like and use them

PUT YOURSELF OUT THERE

Miles from home, I either had to shoot this with the “wrong” lens, or miss the moment. Hey, I lived.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY, IF IT TRULY IS AN ART (and I’m assuming you believe it is), can never get to a place where it’s “done”. There is no Finished, there ain’t no Clock Out, and there shouldn’t be any Good Enough. There is only where you are and the measurable distance between there and where you want to be. And, once you get there, the chains get moved down the field to the next first down, and the whole drill starts over again.

That means that, as photographers, we are always just about to find ourselves uncomfortable, or need to try to make ourselves that way. Standing still equals stale, which, in turn, equals “why bother?” Sure, the first step toward a new plateau always feels like walking off a cliff, but it needs to, if we’re to improve. If your work feels like something you’ve done before, chances are it is. And if a new assignment or challenge doesn’t come from outside yourself, then you’ve got to do something to put the risk back in the process.

You can write your own prescription. Shoot all day with a limited camera. Do everything in b&w. Make yourself compose shots that are the dead opposite of what you believe looks “right”. Use the “wrong” lens for the assignment at hand. Force yourself to do an entire day’s work in the same aperture, shutter speed, or white balance. Just throw some kind of monkey wrench into your routine, before the routine becomes the regular rhythm (spelled “rut”) of your work. The words comfort and create don’t fit comfortably in the same sentence. Be okay with that.

We can’t always count on crazed bosses, tight deadlines or visionary mentors to nudge us toward the next best version of ourselves. Learn how to kick yourself in the butt and you’ll always be in problem-solving mode. That means more mistakes, which in turn means a speedier learning curve. You never learn anything repeating your past successes, so don’t curl up next to them like some comfortable chair. Put it all out there. Make the imperfect day work for you, and pray that there’s another one waiting after that.

WORKING THE BLINDS

I love this building, but the real star of this image is light; where it hides, bounces, conceals, and reveals.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST CHALLENGING ASPECTS OF URBAN PHOTOGRAPHY, versus shooting in rural settings, is the constant variability of light. On its way to the streets of a dense city, light is refracted, reflected, broken, interrupted, bounced and just plain blocked in ways that sunshine on a meadow can never be. As a result, shooting in cities deals with direct light only intermittently: it’s always light plus, light in spite of, light over here, but not over there. And it’s a challenge for all but the most patient photographers. Almost every frame must be planned somewhat differently from its neighbors, for there can be no “standard” exposure strategy.

I often think of city streets as big window sills sitting below a massive set of venetian blinds, with every slat tilted a little differently. And I personally greet this condition as an opportunity rather than a deficit, since the unique patterns of abstraction mean that even mundane scenes can be draped in drama at any given moment. That’s why, as I age, I’ve come to highly value selective lighting, for mood, since I’m convinced that perfectly even lighting on an object can severely limit that selfsame drama.

I’m also reminded of the old Dutch masters painters, who realized that a partially dark face contains a kind of mystery. Conversely, a street scene that contains no dropouts of detail or light makes everything register just about the same with the eye, and can keep your images from having a prominent point of interest. Darkness, by contrast, asks your imagination to supply what’s missing. Even light is a kind of full disclosure, and it can rob your pictures of their main argument, or the “look over here” cue that’s needed to make a photograph really connect.

Back to street photography. Given that glass and metal surfaces, the main ingredients in urban structures, can run a little to silver and blue, I may actually take an unevenly lit scene and either modify it toward those colors with a filter, or simply under-expose by a half-stop to see how much extra mood I can wring out of the situation, as in the above image of an atrium in midtown Manhattan. Think of it as “working” those big venetian blinds. Cities both reveal and conceal, and your images, based on your approach, can serve both those ends.