IT TAKES A THIEF

In this composition, people become mere design elements, or props. To get this look, a single exposure was duped, the two images were re-contrasted, and then blended in the HDR program Photomatix for a wider tonal range than in “nature”.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE GREAT STREET PHOTOGRAPHERS OF OLD WERE ALL WILY, SLY THIEVES, capturing their prey in emulsion. Yes, I know that the old superstition isn’t literally true. You can’t, in fact, imprison someone’s soul inside that little black box. And yet, in a sense that is very personally felt by many of our subjects today, we are committing an “invasion” of sorts, a kind of artsy assault on the self. Oddly, the same technique that gets you admired when you successfully capture a precious quality of someone else’s face makes you despised when you’re sneaking around to get my picture. Whether street shoots are inspired or reviled is largely a matter of who is being “violated”.

We’ve all heard about Henri Cartier-Bresson, covering the bright chrome trim of his Leica with black electrical tape, the better to keep his camera “invisible” to more of his subjects, as well as the through-the-overcoat candids shot on the New York subway by Walker Evans. And then there is the real risk to personal safety, (including being arrested, jailed, and physically threatened) undertaken by Robert Frank when taking the small-town shots for his legendary street collection, The Americans in the 1950’s. And while most of us aren’t risking incarceration or a punch in the snoot when framing up a stranger, sensitivity has accelerated, as cameras have proliferated into the millions, and personal privacy has, in the digital era, been rendered moot.

Every street shooter must therefore constantly re-negotiate the rules of engagement between himself and the world at large. Is the whole of society his canvas, or is he some kind of media criminal, seeking to advance his own vision at the expense of others’ personhood? I must admit that, at times, I tire of the endless calculation, of the games involved in playing “I’m-here-I’m-not-really-here” with individuals. When my fatigue reaches critical mass, I pull back…..way back, in fact, no longer seeking the stories in individual faces, but framing compositions of largely faceless crowds, basically reducing them to design elements within a larger whole. Malls, streets, festivals…the original context of the crowds’ activities becomes irrelevant, just as the relationship of glass bits in a kaleidoscope is meaningless. In such compositions, the people are rendered into bits, puzzle pieces…things.

And while it’s true that one’s eye can roam around within the frame of such images to “witness” individual stories and dramas, the overall photo can just be light and shapes, arranged agreeably. Using color and tonal modification from processing programs like Photomatix (normally used for HDR tonemapping) renders the people in the shot even more “object-like”, less “subject-like”(see the link below on the “Exposure Fusion” function of Photomatix as well). The resulting look is not unlike studying an ant farm under a magnifying glass, thus a trifle inhuman, but it allows me to distance myself from the process of photostalking individuals, getting some much-needed detachment.

Or maybe I’m kidding myself.

Maybe I just lose my nerve sometimes, needing to avoid one more frosty stare, another challenge from a mall cop, another instance of feeling like a predator rather than an artist. I don’t relish confrontations, and I hate being the source of people’s discomfiture. And, with no eager editors awaiting my next ambush pic of Lindsey Lohan, there isn’t even a profit motive to excuse my intrusions. So what is driving me?

As Yul Brynner says in The King & I, “is a puzzlement.”

(follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye and on Flickr at http://www.flickr.com/photos/mpnormaleye)

Related articles

PICTURES FULL OF PICTURES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE FRAME, AS IT HAS BEEN EMPLOYED IN PHOTOGRAPHY, is the visual element that truly sets the terms on which we will engage a picture. The decision of what to include or exclude in the shooter’s specifically defined little universes is the closest one can come to absolute godlike power. Frames enter us into an informal agreement with the photographer, a handshake deal that, yes, we will accept that you are presenting a world bordered by your own vision…whatever its strengths and limits. We enter an image by plunging past the edge of the frame, like the holiday party in Mary Poppins leaping into a sidewalk chalk sketch.

The fun variant in this happens when arrangements of smaller frames arranged within the master frame suggest themselves as a composition that can tell a story all by itself. Odd as it sometimes seems to take “pictures of pictures”, the results can be wonderful, or at least something beyond the mere act of recording. An image showing a wild mass of pinned-up photos of missing persons which is oddly more powerful than a portrait of any one person within it. A wall of randomly sized works within a gallery. A totality of small pictures achieved by merely stepping back, and providing the group with a defining perimeter.

I recently had the good luck to wander into a room within the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) that took me beyond the formal exhibits to a place where a completely new kind of art is constantly being generated. In this room, a children’s art studio, there are no “schools” of painting or “periods” of drawing, just the energetic surge of young minds bursting into productivity on a daily basis. And there, along an entire wall of the workshop, stretched an enormous montage of works of every kind. No themes, no commonalty of conception, just raw, unafraid imagination. The wall, and the two people scanning it (one adult, one child) provided all the story anyone could ever need. The picture took itself.

The frame can frame other frames, and, in doing so, tell very specific truths. It’s a gift when it happens. And there isn’t a photographer alive who doesn’t love a freebie.

(follow Michael Perkins and share your own images on Twitter @mpnormaleye)

PULL DOWN THE NOISE

by MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY OFTEN SPEAKS LOUDER IN A SOFTER VOICE. Think about it. If you accept the idea of visual information as a sort of “sound”, then it’s easy to see why some images don’t make a direct connection with viewers. They are busy, overloaded with information, or, in this metaphor, noisy, loud. Cachophonous. Chaotic. Too many “sounds” competing for attention. In a visual image, “noise” can be anything that keeps anyone from hearing the “voice” of your image. To be seen more clearly, pictures need to go soft, in order to be heard louder.

That usually means simplifying the image. Shaping its tone, its framing, its central message. In photography, we all make the mistake of trying to show everything, and, in the process, creating an overdose of data that sends the viewer’s eye wandering all around the picture, trying to find something, anything, to focus on. We present a three-ring circus where just one would be more than adequate.

A “perfect” exposure would have inhibited the drama inherent in this situation. So we made it more imperfect.

On a recent trip to an art studio in Paradise Valley, Arizona, I was lucky enough to be present when artisans were pouring molten bronze into decorative molds for all us green “touristas”. Capturing the scene “as is” was easy, as I had plenty of time to calculate exposure and lighting. As a result, I got a lot of “acceptable” pictures good enough for the average postcard, but their storytelling quality was only so-so, since they were almost too full of color, detail and people/props. In the moment, I merely recorded a group of people in a crowded shop doing a job. The tonal balance was “perfect” according to the how-to books, as if I had shot the images on full auto. In fact, though, I had shot on manual, as I always do, so where was my imprint or influence on the subject? The pictures weren’t done.

Back home, when my brain had time to go into editor mode, I realized that the glowing cup of metal was the only essential element in the pictures, and that muting the colors, darkening the detail and removing extra visual clutter was the only way that the center of the shot could really shine.

With that in mind, I deepened the shadowy areas, removed several extraneous onlookers and amped up the orange in the cup. Seems absurdly simple, but as a result, the image was now a unique event instead of a generic “men at work” photo. The picture had to use a softer voice to speak louder.

Great picture? Not yet.

But, hey, I’m still young.

Best thing about the creative process, unlike banking, building or brain surgery, is the luxury of do-overs. And doing over the do-overs, over.

Related articles

- On the Nature + Purpose of Photography (statenislandstories.wordpress.com)

THE ROOMS DOWN THE HALL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR THESE PAGES, IT WAS NEVER MY VISION TO MERELY POST PICTURES. Not, at least, without some kind of context. Just meeting a regular deadline with the “picture of the day” held as little interest for me as maintaining a diary, an oppressive regularity that I have resisted my entire life. For the most part, the images on THE NORMAL EYE are here to anchor my thoughts about what it feels like to be enticed, seduced, enthralled, and, yes, disappointed by photography, to caption the frames with some semblance of the creative process, at least as I had the poor power to see it at the time.Like all blogs, it is written on my own very personal terms. I am always thrilled to harvest reaction and comment, since, as Ike Turner once sang, “was my plan from the very began”. But the important thing is to get the thoughts right, or at least to use them as a guide to the shots. Thus, the mission is neither words nor pictures, but some kind of handshake symbiosis between the two.

FOR THESE PAGES, IT WAS NEVER MY VISION TO MERELY POST PICTURES. Not, at least, without some kind of context. Just meeting a regular deadline with the “picture of the day” held as little interest for me as maintaining a diary, an oppressive regularity that I have resisted my entire life. For the most part, the images on THE NORMAL EYE are here to anchor my thoughts about what it feels like to be enticed, seduced, enthralled, and, yes, disappointed by photography, to caption the frames with some semblance of the creative process, at least as I had the poor power to see it at the time.Like all blogs, it is written on my own very personal terms. I am always thrilled to harvest reaction and comment, since, as Ike Turner once sang, “was my plan from the very began”. But the important thing is to get the thoughts right, or at least to use them as a guide to the shots. Thus, the mission is neither words nor pictures, but some kind of handshake symbiosis between the two.

However, since day one, I have reserved several gallery pages on which visual info is pretty much all there is, since I also believe that it is important to react to photographs on a purely visceral basis. If the blog is the main hall in the house, think of these as the rooms down the hall that you never thought to explore.

I have tried to give each gallery its own general feel, since there are different “themes” which motivate our taking of pictures, and I thought, for this post, it might be helpful to underscore those themes just enough to justify how they were organized. I have now also given them specific names instead of the A-B-C tags they had previously.

Here’s the new rundown:

Gallery A is now “HDR”, since I think that this process affords very specific benefits for reproducing the entire range of visible light in a way that, until recently, has been impracticable for many shooters. No tool is suitable for every kind of shooting situation, but HDR comes close to reproducing what the eye sees, and can enhance detail in fascinating ways. There is a lot controversy over its best use, so, like everywhere else on this blog, your opinions are invited.

The former B gallery is a collection of impulse shots. All of these images were taken in the moment, on a whim, with only instinct to guide me. No real formal prep went into the making of any of them, as they were the product of those instants when something just feels right, and you try to snag it before it vanishes. We’ll call these “SNAP JUDGEMENTS”.

And finally, the photos formerly known as Gallery “C” are now renamed “NATURAL STATE”, as these portraits are all shot using available light, captured without flash or the manipulation of light through reflectors, umbrellas, or other tools.

Let me state here that your participation in this forum was always the centerpiece of my doing it in the first place, and your ideas and suggestions have always inspired me to try to be worthy of the space I’m taking up. I also have enjoyed linking back to your individual sites and visions. It’s a great way to learn.

ideas and suggestions have always inspired me to try to be worthy of the space I’m taking up. I also have enjoyed linking back to your individual sites and visions. It’s a great way to learn.

So please know that, when you click the “like” button at the bottom of these posts, or take the time to type a comment, it does help me see what works, as well as what needs to be done better. I don’t believe that art can grow in a vacuum, and I thank everyone for giving these pages shape and form.

And thanks for exploring all the rooms in my house.

LET THERE BE (MORE) LIGHT

A new piece of glass makes everything look better….even another piece of glass. First day with my new 35mm prime lens, wide open at f/1.8, 1/160 sec., ISO 100.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE RECENTLY BEEN EXPERIENCING ONE OF THOSE TIME MACHINE MOMENTS in which I am, again, right back at the beginning of my life as a photographer, aglow with enthusiasm, ripe with innocence, suffused by a feeling that anything can be done with my little black box. This is an intoxication that I call: new lens.

Without fail, every fresh hunk of glass I have ever purchased has produced the same giddy wonder, the same feeling of artistic invincibility. This time out, the toy in question is a Nikon f/1.8 35mm prime lens, and, boy howdy, does this baby perform. For cropped sensor cameras, it “sees” about like the 50mms of old, so its view is almost exactly as the human eye sees, without exaggerated perspective or angular distortion. Like the 50, it is simple, fast, and sharp. Unlike the 50, it doesn’t force me to do as much backing up to get a comfortable framing on people or near objects. The 35 feels a little “roomier”, as if there are a few extra inches of breathing space around my portrait subjects. Also, the focal field of view, even wide open, is fairly wide, so I can get most of your face tack sharp, instead of just an eye and a half. Matter of preference.

All this has made me marvel anew at how fast many of us are generally approaching the age of flashless photography. It’s been a long journey, but soon, outside the realm of formal studio work, where light needs to be deliberately boosted or manipulated, increasingly thirsty lenses and sensors will make available light our willing slave to a greater degree than ever before. For me, a person who believes that flash can create as many problems as it solves, and that it nearly always amounts to a compromise of what I see in my mind, that is good news indeed.

It also makes me think of the first technical efforts to illuminate the dark, such as the camera you see off to the left. The Ermanox, introduced by the German manufacturer Ernemann in 1924, was one of the first big steps in the quest to free humankind of the bulk, unreliability and outright danger of early flash. Its cigarette-pack-sized body was dwarfed by its enormous lens, which, with a focal length of f/2, was speedy enough (1/1000 max shutter) to allow sharp, fast photography in nearly any light. It lost a few points for still being based on the use of (small) glass plates instead of roll film, but it almost single-handedly turned the average man into a stealth shooter, in that you didn’t have to pop in hefting a lotta luggage, as if to scream “HEY, THE PHOTOGRAPHER IS HERE!!” In fact, in the ’20’s and ’30’s, the brilliant amateur shooter Erich Solomon made something of a specialty out of sneaking himself and his tiny Ermanox into high-level government summits and snapping the inner circle at its unguarded best (or worst). Long exposures and blinding flash powders were no longer part of the equation. Candid photography had crawled out of its high chair… and onto the street.

Today or yesterday, this is about more than just technical advancement. The unspoken classism of photography has always been: people with money get great cameras; people without money can make do. Sure, early breakthroughs like the Ermanox made it possible for anyone to take great low-light shots, but at $190.65 in 1920’s dollars, it wasn’t going to be used at most folks’ family picnics. Now, however, that is changing. The walls between “high end” and “entry level” are dissolving. More technical democracy is creeping into the marketplace everyday, and being able to harness available light affordably is a big part of leveling the playing field.

So, lots more of us can feel like a kid with a new toy, er, lens.

Related articles

- Prime Lenses (nikonusa.com)

- Understanding Focal Length (nikonusa.com)

REWORKING THE UNIVERSE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CONTEXT, FOR A PHOTOGRAPHER, IS LIKE THE CONDUCTOR’S BATON IN MUSIC, that magic wand that dictates fast and slow, soft and loud, ordering a specific world within a confined space. Since it impossible to show the world entire, all shooters decide what part of it, what story within it, that they will frame. Sounds obvious, but without the mastery of this skill, we fail as storytellers, and the eye that we develop for what to include and exclude is, despite all the tools and toys, the only thing that really makes an artistic performance out of a photograph.

It can also be a helluva lot of fun. With some dumb luck thrown in for good measure.

Cactropolis, 2011. A three-exposure HDR blend with a little color and contrast teaking. This whole layout, in reality, is about fifteen feet square, total. Various shutter speeds, f/8, ISO 100, 52mm.

I love opportunities that allow me to disrupt the original visual “place” of objects, to force them to be re-purposed for the viewer. A few years ago, my daily lunch routine involved a short walk across a bustling college campus to my habitual lunch hang, a stroll which took me past one of the school’s busiest crossroads, marked by the intersection of two superwide sidewalks flanked by small patches of landscaping. Since this is Arizona, such short plots of land frequently are not the stuff dreams are made of. We’re talking pink quartz gravel interrupted by the occasional scabby aloe plant or cholla. And that’s what made this one little rectangle, just several feet long on each side, vie for my attention.

An arrangement of several varieties of small cacti has been arranged in rows, regulated by square tiles, grounded in gravel, and bounded by smooth bluish stones. Simple stuff, really, but this was somebody’s deliberate design, a pattern that registered, to my eye, like some kind of fantasy urban streetscape, blocks of tiny, spiny skyscrapers vanishing off toward an unseen horizon….a miniature downtown from Weirdsville, a tabletop diorama from Beetlejuice.

I didn’t really have to compose anything. I was in the framing business. But getting that frame meant getting rid of the surrounding throngs of students, the sidewalks, the buildings, the sky…..anything that seemed outside of the closed world implied by that little rectangle. Changing the context. In fact, I was adding something for everything I was taking away.

So let’s crop this puppy and see what happens.

Now I saw what seemed to be a self-contained world, one in which I was free to imagine what lay “beyond”. I goosed up the hues and texture with HDR processing, but otherwise, what you see is what there was. Maybe it works as pure design. Maybe I conveyed something, but the fact is, we have to make choices as shooters. The only thing that marks us as individuals is what we decide to see, and show.

Like I said…fun….luck….some other somethings…..

(Many Thanks Dept.:The idea for this post was inspired, in part, by a suggestion from my good friend Michael Grivois.)

THE OTHER 50%

By MICHAEL PERKINS

The American Dream, Pacific Grove, California, 2012. A three-exposure HDR with shutter speeds ranging from 1/100 to 1/160, all three shots at f/8, ISO 100, 32mm.

THE LAST SUNDAY EDITION OF THE NEW YORK TIMES FOR 2012 features its annual review of the year’s most essential news images, a parade of glory, challenge, misery and deliverance that in some ways shows all the colors of the human struggle. Plenty of material to choose from, given the planet’s proud display of fury in Hurricane Sandy, the full scope of evil on display in Syria, and the mad marathon of American politics in an electoral year. But photography is only half about recording, or framing, history. The other half of the equation is always about creating worlds as well as commenting on them, on generating something true that doesn’t originate in a battlefield or legislative chamber. That deserves a year-end tribute of its own, and we all have images in our own files that fulfill the other 50% of photography’s promise.

This year, for example, we saw a certain soulfulness, even artistry, breathed into Instagram and, by extension, all mobile app imaging. Time ran a front cover image of Sandy’s ravages taken from a pool of Instagramers, in what was both a great reportorial photo and an interpretive shot whose impact goes far beyond the limits of a news event. Time and again this year, I saw still lifes, candids, whimsical dreams and general wonderments of the most personal type flooding the social media with shots that, suddenly, weren’t just snaps of the sandwich you had for lunch today saturated with fun filters. It was a very strong year for something personal, for the generation of complete other worlds within a frame.

I love broad vistas and sweeping visual themes so much that I have to struggle constantly to re-anchor myself to smaller things, closer things, things that aren’t just scenic postcards on steroids, although that will always be a strong draw for me. Perhaps you have experienced the same pull on yourself…that feeling that, whatever you are shooting, you need to remember to also shoot…..something else. It is that reminder that, in addition to recording, we are also re-ordering our spaces, assembling a custom selection of visual elements within the frame. Our vision. Our version. Our “other 50%.”

My wife and I crammed an unusual amount of travel into 2012, providing me with no dearth of “big game” to capture…from bridges and skyscrapers to the breathlessly vast arrays of nature. But always I need to snap back to center….to learn to address the beauty of detail, the allure of little composed universes. Those are the images I agonize over the most at years’ end, as if I am poring over thumbnails to see a little piece of myself , not just in the mountains and broad vistas, but also in the grains of sand, the drops of dew, the minutes within the hours.

Year-end reviews are, truly, about the big stories. But in photography, we are uniquely able to tell the little ones as well. And how well we tell them is how well we mark that we were here, not just as observers, but as participants.

It’s not so much how well you play the game, but that you play.

Happy New Year, and many thanks for your attention, commentary, and courtesy in 2012.

Related articles

- 10 social mobile photography trends for 2013 (davidsmcnamara.typepad.com)

- Old-Timer Joins Instagram, Schools Everyone With Poignant Flood Photos (wired.com)

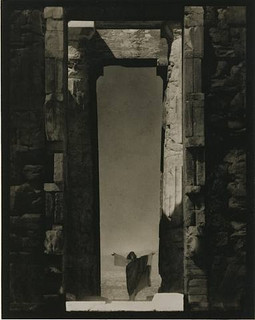

I SEE YOUR FACE BEFORE ME

Edward Steichen’s amazing 1921 portrait of dance icon Isadora Duncan beneath a massive arch of the Parthenon in Greece, an image which recently surged to the top of my mind. See a link to a larger view of this shot, below.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE IMAGES SIT AT THE BOTTOM OF THE BRAIN, LIKE STONE PILLARS IN THE FOUNDATION OF AN IMMENSE TOWER.The structures erected on top of them, those images we ourselves have fashioned in memory of these foundations, dictate the height and breadth of our own creative edifices. Between these elemental pictures and what we build on top of them, we derive a visual style of our own.

In my own case,many of the pillars that hold up my own house of photography come from a single man.

Edward Steichen is arguably the greatest photographer in history. If that seems like hyperbole, I would humbly suggest that you take a reasonable period of time, say, oh, twenty years or so, just to lightly skim the breadth of his amazing career….from revealing portraits to iconic product shots to nature photography to street journalism and half a dozen other key areas that comprise our collective craft of light writing. His work spans the distance from wet glass plates to color film, from the Edwardian era to the 1960’s, from photography as an insecure imitation of painting to its arrival as a distinct and unique art form in its own right.

At the start of the 20th century, Steichen co-sponsored many of the world’s first formal photographic galleries, and was a major contributor to Camera Work, the first serious magazine dedicated wholly to photography. He ended his career as the creator of the legendary Family Of Man, created in the early 1950’s and still the most celebrated collection of global images ever mounted anywhere on earth. He is, simply, the Moses of photography, towering above many lesser giants whose best work amounts to only a fraction of his own prodigious output.

Which is why I sometimes see fragments of what he saw when I view a subject. I can’t see with his clarity, but through the milky lens of my own vision I sometime detect a flashing speck of what he knew on a much larger scale, decades before. The image at left recently rocketed to my mind’s eye several weeks ago, as I was framing shots inside a large government building in Ohio.In 1921, Steichen journeyed to Greece to use the world’s oldest civilization basically as a prop for portraits of Isadora Duncan, then in the forefront of American avant-garde dance. Framing her at the bottom of an immense arch in the ruins of the Parthenon, he made her appear majestic and minute at the same time, both minimized and deified by the huge proportions in the frame. It is one of the most beautiful compositions I have ever seen, and I urge you to click the Flickr link at the end of this post for a slightly larger view of it. (Also note the link to a great overview of Steichen’s life on Wikipedia.)

Uplighting creates a moody frame-within-frame feel at the Ohio Statehouse building, in a shot inspired by Edward Steichen’s images of massive arches. 1/30 sec., f/8, ISO 800, 18mm.

In framing a similarly tall arch leading into the rotunda of the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus, I didn’t have a human figure to work with, but I wanted to show the building as a series of major and minor access cavities, in, around, under and through one of its arched entrance to the central lobby. I kept having to back up and step down to get at least a partial view of the rotunda and the arch at the opposite end of the open space included in the frame, which created a kind of left and right bracket for the shot, now flanked by a pair of staircases. Given the overcast sky meekly leaking grey light into the rotunda’s glass cupola, most of the building was shrouded in shadow, so a handheld shot with sufficient depth of field was going to call for jacked-up ISO, and the attendant grungy texture that remains in the darker parts of the shot. But at least I walked away with something.

What kind of something? There is no”object” to the image, no story being told, and sadly, no dancing muse to immortalize. Just an arrangement of color and shape that hit me in some kind of emotional way. That and Steichen, that foundational pillar, calling up to me from the basement:

“Just take the shot.”

Related articles

- The Photograph as a Social Statement (halsmith.wordpress.com)

- Picture Imperfect (andrewsullivan.thedailybeast.com)

- http://www.flickr.com/photos/quelitab/5793648357/lightbox/

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Steichen

DREAMS DOWN TO DUST

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT WAS, ON ONE LEVEL, A COMPLETE WASTE OF GASOLINE: a half-hour’s drive to a dusty cluster of tables scattered across a vacant lot in Carefree, Arizona; a gathering of junk gypsies, hunkering for shade under their teepee nation of display tents, their sprawls of pre-owned debris bunched onto card tables filled with the remains of people’s lives. It was going to take exactly five minutes to make one sad pass around this serpentine mound of resale refuse. No treasures today. Maybe we have time to catch lunch before we drive back to town.

These strange mash-ups of godforsaken bric-a-brac are common in many of the small towns of the southwest. Sometimes they are found shoehorned into sagging old adobe buildings on their umpteenth re-use. Other times they are charitably called “swap meets” or “vintage sales” and litter the parking lots of down-and-out drive-in theatres like the aftermath of an air crash. The visual impact is always the same, that of an attic that has been dynamited to bits, then shoveled into milk cartons and slapped with improvised glo-orange price tags. Coffee cans filled with unrelated fragments of trinkets; cardboard cartons overflowing with random chunks of household backfill. Two mysteries pervade: where has all of this come from….and where can it possibly be heading?

I was about one minute away from the end of my doleful tour when I spotted this box, which someone had filled with mis-matched bits of small dolls. One of such souvenirs on a big table makes no visual impression whatever, but a mass of them together is some kind of little minor-key symphony of dreams gone down to dust. Loved objects that were once transformed into the stuff of fancy, now just shards of lives dumped into a cigar box. I risked one picture. For some reason it haunts me.

But see what you think.

It isn’t about what we look at but what we see.

We leave such a colossal wake of trash behind us as our lives thunder and crash through the world. How to sort out all the stories inside?

WHEN THE NOISE DIES

In the day, this place is a madness of color and noise. At night, you have its wonders all to yourself. Fisherman’s Wharf in Monterey, California. 25 second exposure at f/10, ISO 100, 24mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AMERICA IS A LOUD PLACE. IF WE DON’T HEAR NOISE WHEREVER WE GO, WE CREATE OUR OWN. It is a country whose every street rings with a cascade of counterpointed voices, transactions, signals, warnings, all of it borne on the madly flapping wings of sound. There are the obvious things, like car horns, screeching tires, soaring planes, thundering rails, somebody else’s music. And then there are the almost invisible hives of interconnecting lives that tamp vibration and confusion into our ears like a trash compactor.

We no longer even notice the noise of life.

In fact, we are vaguely thrown off-balance when it subsides. We need practice in remembering how to get more out of less.

That’s why I love long night exposures. It allows you to survey a scene after the madding crowd has left. Leaving for their dates, their destinies, their homes, they desert the fuller arenas of day and leave it to breathe, and vibrate, at a more intimate rhythm. Colors are muted. Shadows are lengthened. The sky itself becomes a deep velvet envelope instead of a sun-flooded backdrop.

The noise dies, and the quiet momentarily holds the field.

The above image is of Monterey’s Fisherman’s Wharf, one of the key tourist destinations in California, a state with an embarrassment of visual riches. During the day, it is a mash of voices, birdcalls, the deep croak of harbor seals, and the boardwalk come-ons of pitchmen hawking samples of chowder along the wharf’s clustered row of seafood joints. It is a colorful cacophony, but the serenity that descends just after dark on cold or inclement nights is worth seeking out as well.

Setting up a tripod and trying to capture the light patterns on the marina, I was stacking up a bunch of near misses. I had to turn my autofocus off, since dark subjects send it weaving all over the road, desperately searching for something to lock onto. I am also convinced that the vibration reduction should be off during night shots as well, since….and this is counter-intuitive….it creates the look of camera shake when it can’t naturally find it. Ow, my brain hurts.

The biggest problem I had was that, for exposures nearing thirty seconds in length, the gentle roll of the water, nearly imperceptible to the naked eye, was consistently blurring many of the boats in the frame, since I was actually capturing half a minute of their movement at a time. I couldn’t get an evenly sharp frame, and the cold was starting to make me wish I’d packed in a jacket. Then, out of desperation, I rotated the tripod about 180 degrees, and reframed to include the main cluster of shops along the raised dock near the marina. Suddenly, I had a composition, its lines drawing the eye from the front to the back of the shot.

More importantly, I got a record of the wharf’s nerve center in a rare moment of calm. People had taken their noise home, and what was left was allowed to be charming.

And I was there, for both my ear and my eye to “hear” it.

Thoughts?

Related articles

- Vibration Reduction (nikonusa.com)

HANDS OFF. SORT OF.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE SHOULD BE CURATED SHOWS AT MUSEUMS ALL OVER THE WORLD JUST FOR SNAPSHOTS. It’s already a known fact that images taken in an impulsive instant are among the most emotionally immediate in history. What these billions of “shooting from the hip” pictures share is the uncompromised commitment of hitting that button, and letting what happens, happen. Of course, back in the day, many of us had no choice in the matter, especially with our earliest cameras. Sadly, sometimes the box was too dumb, too seized up in tech cramps to guess what we wanted. Today, however, we can’t blame the camera anymore if we fail to live in the moment. They are world-class enablers. If we didn’t get the shot, we need to be smarter.

Sometimes you gotta shoot ’em quick and hope. Available light and less of it every second: 1/200, f/8, ISO 100, 20mm.

And, to be fair, we are smarter, even in those just-shoot-it-moments. The amazing complexity of today’s captures on automatic modes has saved us the trouble, more than at any time in history, of having to put on the twin hats of physicist and chemist. That should mean scads of instances when we can truly trust our instincts and hand the dirty work off to the camera with a reasonable hope of getting what we were after.

Now, in the modern world, comes the tricky part.

We may now know too much, compared to the cavemen we were in the earliest days of photography. And, once we begin to comprehend the totality of tweaking, calculation, and post-processing that are available to “rescue” more of our shots, it’s amazingly hard to avoid availing ourselves of all of it. We can remove the tiniest mote of dust, conveniently wipe out the crummy telephone wires, erase the ex-girl friend at the wedding. Trickier still, if we shoot on manual mode, we can practically think the process to death, essentially bleeding the adventure and spontaneity out of at least some images that we should just shoot.

There will always be shots that are so complete in themselves that continuing to fiddle with them before shooting will just have a diminishing return, little gifts of the moment that are so nearly perfect already that you could render them lifeless by trying to “perfect” them. Important: this is not an argument for super-gluing your mode dial to the auto position, since that can also create a string of acceptable exposures that fall short of being compelling pictures.

The balance, the aggravation, and eventually, the joy, lies somewhere in the middle.

Once the sun starts to set in Arizona, you’re racing the light to the horizon, so he who hesitates is lost. Shot on the fly at 1/160 sec., f/11, ISO 100, 18mm.

This is the kind of sunset that only becomes possible near the end of the rainy season (a relative term!) in the Sonoran desert. You get more days with at least some clouds overhead, breaking the mega-blue monotony of the southwestern sky. And you get wonderful gradations of color as the last light of day vanishes over the horizon. In this image, that light was changing, and leaving, rapidly. Not a lot of time to weigh options, but a perfect place to flail away and maybe get something. This was not shot on auto mode, but I made a very quick, simple calculation in manual, and kept the prep as brief as possible. Later on, I was tempted again to go on tinkering, considering a lot of little “fixes” to “improve” my result. To my eventual satisfaction, I sat on my hands, and so what you see is what I got…no frills, no fuss, no interfering with my self.

It would probably be a great exercise to compile your own personal museum exhibit of the best pictures that you successfully left alone, the captures that most validate your instincts, your impulse, your artistic courage. And, certainly I would love to see them linked back to this blog, as conversation between all of us is what I value most about the project.

Go for it.

Related articles

- Getting Started: How to Hold Your Camera (nikonusa.com)

BEAUTIFUL LOSERS

Shooting on the street is bound to give you mixed results. I have been messing with this shot of a Brooklyn coffee shop for days, and I still can’t decide if I like it. 1/80 sec., f/5, ISO 100, 24mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE A LOT OF INSTANTANEOUS “KEEP” OR “LOSE” CALLS that are made each day when first we review a new batch of photos. Which to cherish and share, which to delete and try to forget? Thumbs up, thumbs down, Ebert or Roper. Trash or treasure. Simple, right?

Only, the more care we take with our shooting, the fewer the certainties, those shots that are immediately clear as either hits or misses. As our experience grows, many, many more pictures fall into the “further consideration” pile. Processing and tweaking might move some of them into the “keep” zone, but mostly, they haunt us, as we view, re-view and re-think them. Even some of the “losers” have a sort of beauty, perhaps for what they might have been rather than what they turned out to be. It’s like having a kid that you know will always be “C” average, but who will never stop reaching for the “A”, God love their heart.

I have thousands of such pictures now,pictures that I study, weep over, slap my forehead about, ask “what was I thinking?” about. I never have been one for doing a reflexive jab on the “delete” button as I shoot, as I believe that the near misses, even more than the outright disasters, teach us more than even the few lucky aces. So I wait at least to see what the shot really looks like beyond the soft deception of the camera monitor. I buy the image at least that much time, to really, really make sure I dropped a creative stitch.

Many times my initial revulsion was correct, and the shot is beyond redemption.

Ah, but those other times, those nagging, guilt-laden re-thinks, during which I get to twist in the wind a little longer. Pretty? Ugly? Genius? Jerk? Just like waiting for an old Polaroid to gradually fade in, so too, the ultimate success or failure of some pictures takes a while to emerge. And even then, well, let’s come back and look at this one later…….

The above frame, taken while I was walking toward the pedestrian ramp to the Brooklyn Bridge, is just such a shot. My wife stepped into a coffee shop just fast enough to grab us some bottled water, while I waited on the sidewalk trying to make my mind up whether I had anything to shoot. As you can see, what I got could be legitimately called a fiasco. Nice color on the store’s neon sign, and a little “slice of life” with the customer checking out at the register, but then it all starts to mush into a hot mess, with the building and car across the street eating up so much of the front window that your eye is dragged all over the place trying to answer the musical question, “what are we doing here?” Storefront shots are a real crap shoot. That is, sometimes you have something to shoot, and sometimes you just have crap.

Even at this point, with more than a few people giving the shot a thumbs-up online, I can’t be sure if I just captured something honest and genuine, or if I’ve been reading too many pointy-headed essays on “art” and have talked myself into accepting a goose egg as something noble.

But as I said at the top of this piece, the choices get harder the more kinds of stuff you try. If you shoot your entire life on automode, you don’t have as many shots that almost break your heart. I wonder what my personal record is for how long after the fact I’ve allowed myself to grieve over the shots that got away. It’s tempting to hit that delete button like a trigger-happy monkey and just move on.

But, finally, the “almosts” show you something, even if they just stand as examples of how to blow it.

And that is sometimes enough to make the losers a little bit beautiful.

Thoughts?

180 DEGREES

This image, the reason I ventured out into the night, originally eluded me, causing me to turn a half circle to discover a totally different scene and feel waiting just over my shoulder. 20 sec., f/8, ISO 100, 20mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I WISH I HAD A LEICA for every time I came away from a shooting project with something completely opposite from the prize I was originally seeking. The odd candid moment, the last-minute change of light, the bizarre intervening event….there are so many random factors even in the shots that are the most meticulously planned that photography is kept perpetually fresh, since it is absolutely impossible to ensure its end results, especially for infants playing at my level. That point was dramatically brought home to me again a few weeks ago, and all I had to do was turn my head 180 degrees.

All during a week’s stay at a conference center near Yosemite National Park, I had been struck by how the first view a visitor got of the main lodge and its surrounding pond, from an approach road slightly above the building, was by far a better framing of the place than could be had anywhere else on the grounds. A few days of strolling by the lodge from several approaches had not provided any better staging of the quiet scene, but, with the harshness of the daylight at that altitude, I was convinced that a long exposure done just after nightfall would convey a more peaceful, intimate mood than I could ever hope to capture by day. And so, on the evening before I was to leave the lodge for home, I decided to take my tripod to the approach road and set up for a try.

The road is rather twisty and narrow, and so its last turn before heading for the lodge’s parking areas is lit with a street lamp, and a bloody bright one at that. It’s a sodium vapor light, which registers very orange to the eye. I’m used to these monsters, since, back home in Phoenix, they are the predominant city light sources, creating less long-distance “light pollution” for astronomers in Flagstaff trying to see the finer features in the night sky. At any rate, the road was so bright that I had to set up closer to the lodge than originally planned in order to avoid a lot of ambient light over my shoulder killing the subdued dark I wanted for my shot. Intervening event and last-minute change of light. Changing my stance, I was also having problems with movement on the pond surface. It was a tad too swift to allow for a mirroring of the lodge, and a long exposure was going to soften it up even more. I was going to get pretty colors, but they would be diffuse and gauzy rather than reflective. At the same time I was trying to avoid framing another lamp, this one to the right of the lodge. Illuminating a walking path, it would, over the length of the exposure, pretty much burn its way into the scene and distract from the impact. Typical problems, but I was already losing my love for the project, and after about a half-dozen flubbed attempts, I was trying to avoid mouthing several choice Anglo-Saxon epithets.

It was the need to take a break that had me looking around to see if anything else could be done under the conditions, and that’s when I turned my head to really see the light from the approach road that had been over my shoulder. Candid moment. Now I saw that orange light illuminating the road, the rustic fence, and the surrounding trees and shrubs in an eerie, Halloween-ish cast. The same scene in daylight or natural color would have registered just as “some nice trees”, but now it was Sleepy Hollow, the scary walk home after the goblins come out, the place where evil things breed. Better yet, if I stepped just about six inches to the right of where I was standing, the hated lamp-post would be totally obscured by the largest tree in the shot, casting its shadow another 20 or so feet longer and serving up a little added drama as a bonus. Suddenly, the lamp had been transformed from a fiend to a friend. I swiveled the tripod’s head around, set the shot, and got where I needed to be in two clicks.

After first trying (and failing) to nail the image of the lodge, I pivoted around and found this scene, which had been waiting to be discovered right behind me. Once I shot this, I turned around and made one more attempt on the lodge, using, as it turned out, the exact same setting as this picture; 20 sec., f/8, ISO 100, 20mm.

Better yet, the break in the action allowed me to re-boot my head vis-a-vis the lodge image. I turned back around, and, oddly, with the exact same exposure settings, hit a balance I could live with. Neither shot was perfect, but the creation of one had actually enabled the capture of the other. On the walk back to my cabin, I was already dissecting the weaknesses in both, but they each, in turn, had taught me, again, the hardest lessons, for me, in photography. Slow down. Look. Think. Plan, but don’t be afraid of reactive instinct. Sometimes, a sacred plan can keep you from “getting the picture”, figuratively and literally.

All I have to do is remember to turn my head around.

A BOX FULL OF ALMOSTS

Shooting for 3D (top image) often cost me a lot of composition space, forcing me to frame in a narrow vertical range, but learning to frame my message in those cramped quarters taught me better how to draw the viewer “in deep” when composing flat 2D images.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I RECENTLY SPENT AN ANGUISHED AFTERNOON sifting through a box of prints that I shot from about 1998 through 2002, a small part of my amateur work overall, but a particularly frustrating batch of images to revisit. Even given the high number of shots of any kind that one has to take to get a small yield of cherished images, the number of “keepers” from this period is remarkably low. It is a large box of almosts, a warehouse of near misses. Still, I felt that I needed to spend some “quality time” (strange phrase) mentally cataloguing everything that went wrong. I could have used a stiff drink.

One reason that the failure rate on these pictures was so high was because the pictures, all of them stereoscopic, were taken with one of the only cameras available for taking such shots at the time. The Argus 3D was an extremely limited film-based point-and-shoot which had been introduced for the sole purpose of producing cheap prints that could be developed by any vendor with conventional processing. The resulting 4×6 prints from the Argus were not the red-green anaglyph shots requiring the infamous cardboard glasses to decipher their overlaid images. but single prints made up of two side-by-side half-frame images in full color, which could later be inserted into an accompanying split-glass viewer that came with the camera.

The 3D effect was, in fact, quite striking, but the modest camera exacted a price for producing this little miracle. Since stereo works more dramatically at longer focal lengths, only shots made at f/11 or f/16 were offered on the Argus, which also had a fixed shutter speed and could not accommodate films rated higher than ASA 100. As for better 3D cameras, most available in the late ’90’s were dusty old relics from the late ’40’s and ’50’s, meaning that any hobbyist interested in stereo photography had to pretty much accept the built-in limitations of the rigs that were available. As a result, I had only basic control over exposure; light flares would invariably create huge streaks on one of the two angled lenses, creating a headache-y “flicker” in the viewing of the final print; and, worst of all, you had to compose every shot in vertical orientation, regardless of subject, in half the width in which you normally worked.

Worse for the artistic aspect of the project, I seem to have been sucked into the vortex that traps most shooters when learning a new technique; that is, I began to shoot for the effect. It seems to have been irrelevant whether I was shooting a bouquet of roses or a pile of debris, so long as I achieved the “eye-poke” gimmick popping out of the edge of the frame. Object (and objectives) became completely sidelined in my attempts to either “wow” the viewer or overcome the strictures of the camera itself. The whole carton of prints from this period seems to be a chronicle of a man who has lost his way and is too stubborn to ask directions. And of the few technically acceptable images in this cluster of shots, fewer still can boast that the stereoscopic element added anything to the overall impact of the subject matter. Can I have that drink now?

A few years later, I would eventually acquire a 1950’s-vintage Sawyer camera (designed to make amateur View-Master slides), which would allow me to control shutter speed, film type, and depth of field. And a few years after that, my stereo shots started to be pictures first, thrill rides second. Grateful as I was for the improved flexibility, however, the Argus’ cramped frame had, indeed, taught me to be pro-active and deliberate in planning my compositions. Learning to shoot inside that cramped visual phone booth meant that, once better cameras gave me back the full frame, I had developed something of an eye for where to put things. Even in 2D, I had become more aware of how to draw the eye into a flat shot.

Today, as I have consigned 3D to an occasional project or two, the lessons learned at the hands of the cruel and fickle Argus serve me in regular photography, since I remain reluctant to trust even more advanced cameras to make artistic decisions for me. Thus, even in the current smorgasbord of optical options, I feel that, in every shot, I am still the dominant voice in the discussion.

That makes all those “almosts” worth while.

Almost.

Bartender? Another round.

Thoughts?