COMMANDER-IN-GRIEF

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MANY OF THOSE WHO TRAVEL TO WASHINGTON, D.C.’s VARIOUS MONUMENTS each year generally strike me as visitors, while those who throng to the memorial honoring Abraham Lincoln seem more like pilgrims. Scanning the faces of the children and adults who ascend the slow steps to the simple rectangular chamber that contains Daniel Chester French‘s statue of the 16th president, I see that this part of the trip is somehow more important to many, more fraught with a sense of moment, than the other places one may have occasion to view along the National Mall. This is, of course, simply my subjective opinion. However, it seems that this ought to be true, that, even more than Jefferson, Washington or any other single person attendant to the creation of the republic, Lincoln, and the extraordinary nature of his service, should require an extra few seconds of silent awe, and, if you’re a person of faith, maybe a prayer.

This week, one hundred and fifty years ago, the gruesome and horrific savagery of the Civil War filled three whole days with blood, blunder, sacrifice, tragedy, and finally, a glimmer of hope, as the battle of Gettysburg incised a scar across every heart in America. Lincoln’s remarks at the subsequent dedication of the battlefield placed him in the position of official pallbearer for all our sorrows, truly our Commander-In-Grief. Perhaps it’s our awareness of the weight, the loneliness, the dark desolation of that role that makes visitors to the Lincoln Memorial a little more humble, a little quieter and deeper of spirit. Moreover, for photographers, you want more of that statue than a quick snap of visiting school children. You want to get something as right as you can. You want to capture that quiet, that isolation, Lincoln’s ability to act as a national blotter of sadness. And then there is the quiet resolve, the emergence from grief, the way he led us up out of the grave and toward the re-purposing of America.

The statue is a simple object, and making something more eloquent than it is by itself is daunting.

The interior of the monument is actually lit better at night than in the daytime, when there is a sharp fall-off of light from the statue to the pillars and colored glass skylights to its right and left. You can crank up the ISO to retrieve additional detail in these darker areas, but you risk the addition of grainy noise. In turn, you can smooth out the noise later, but, in so doing, you’ll also smear away the beautiful grain in the statue itself.

In my own case, I decided to take three bracketed exposures, all f/5.6, , nice and wide at 20mm, low noise at ISO 100, with shutter speeds of 1/50, 1/100, and 1/200. In blending the three later in Photomatix’ Detail Enhancement mode, I found that the 1/200 exposure had too little information in it, so a composite of the three shots would have rendered the darkest areas as a kind of black mayonnaise, so I did the blend with only two exposures. Stone being the main materials in the subject, I could jack up the HDR intensity fairly high to accentuate textures, and, for a more uniform look across the frame, I gently nudged the color temperature toward the brown/amber end, although the statue itself is typically a gleaming white. The overall look is somewhat more subdued than “reality”, but a little warmer and quieter.

Abraham Lincoln was charged with maintaining a grim and faithful vigil at America’s bedside, in a way that no president before or since has had to do. Given events of the time, it was in no way certain that the patient would pull through. That we are here to celebrate his victory is a modern miracle, and the space his spirit occupies at the Lincoln Memorial is something photographers hunger to snatch away for their own.

What we try to capture is as elusive as a shadow, but we need to own something of it. The commander-in-grief’s legacy demands it.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

Related articles

- Other Proposed Designs for the Lincoln Memorial (ghostsofdc.org)

- Lincoln Memorial Under Construction (ghostsofdc.org)

LESS SHOWS MORE

You don’t have to reveal every stray pebble or every dark area in perfect definition to get a sense of texture in this shot. 1/160 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

by MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS A WRONG-HEADED IDEA OUT THERE THAT ALL VISUAL OUTCOMES IN PHOTOGRAPHY SHOULD BE EQUAL. That’s a gob of words, so here’s what I’m getting at: higher ISO sensitivity, post-processing and faster lenses have all conspired, of late, to convince some of us that we can, and should, rescue all detail in even the most constrasty images. No blow-outs in the sky, no mushiness in the midrange, no lost information in the darkest darks. Everything in balance, every iota of grain and pattern revealed.

Of course, that is very seductive. Look at a well-processed HDR composite made from multiple bracketed images, in which the view out the window is deep and colorful, and the shadowy interiors are rich with texture. We’ve seen people achieve real beauty in creating what is a compelling illusion. But, like every other technique, it can come to define your entire output.

It’s not hard to see shooters whose “style” is actually the same effect applied to damn near all they shoot, like a guy who dumps ketchup on everything his wife brings to the table. When you start to bend everything you’re depicting to the same “look”, then you are denying yourself a complete range of solutions. No one could tell you that you always have to shoot in flourescent light, or that deep red is the only color that conveys passion, so why let yourself feel trapped in the habit of using HDR or other processes to always “average out” the tonal ranges in your pictures? Aren’t there times when it makes sense to leave what I will call “mystery” in the undiscovered patches of shadow or the occasional areas of over-exposure?

Letting some areas of a frame remain in shadow actually tamps down the clutter in a busy image like this. 1/60 sec., f/3.2, ISO 100, 35mm.

I am having fun lately leaving the “unknowns” in mostly darker images, letting the eye explore images in which it can NOT clearly make out ultimate detail in every part of the frame. In the mind’s eye, less can actually “show” more, since the imagination is a more eloquent illustrator than any of our wonderful machines. Photography began, way back when, rendering its subjects as painters did, letting light fall where it naturally landed and leaving the surrounding blacks as deep pools of under-defined space. Far from being “bad” images, many of these subtle captures became the most hypnotic images of their era. It all comes down to breaking rules, then knowing when to break even the broken rule as well.

Within this post are two of the latest cases where I decided not to “show it all”. Call it the photo equivalent of a strip-tease. Once you reveal everything, some people think the allure is over. The point I’m making is that the subject should dictate the effect, never the other way around. Someone else can do their own takes on both of these posted pictures, take the opposite approach to everything that I tried, and get amazing results.

There never should be a single way to approach a creative problem. How can there be?

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @thenormaleye.

Related articles

- HDR Under Control is a Thing of Beauty (thewayeyeseesit.com)

GET LOST

Straight through the windshield, using a technique I like to call “dumb luck”. Original shot specs: 1/320 sec., f/8, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY IS 10% PLANNING, 90% SERENDIPITY. Yes, I know. we would all rather believe that most of our images spring from brilliant conceptions, master plans, and, ahem, stunning visions. But a lot of what we do amounts to making the most of what fate provides.

There is no shame in this game. In fact, the ability to pivot, to improvise, to make the random look like the intentional…all of these things reveal the best in us. It exercises the eye. It flexes the soul. And, in terms of images, it delivers the goods.

Getting lost (geographically, not emotionally) is less an emergency than in ages past. Armed with smartphones, GPS, and other hedges against our own ignorance, we can get rescued almost as soon as we wander off the ranch. It is easier than ever to follow the electronic trail of crumbs back to where we belong, so drifting from the path of righteousness is no longer cause for panic. Indeed, for shooters, it’s pure opportunity.

Okay, so you’re not where you’re supposed to be. Fine. Re-group and start shooting. There is something in all these “unfamiliar” things that is worth your gaze.

Last week , my wife and I decided to trust her car’s onboard guidance system. The results were wrong but interesting. No danger, just the necessary admission that we’d strayed really far afield of our destination. We’re talking about twenty minutes of back-tracking to set things right.

But first….

One of the rural roads we drifted down, before realizing our error, led us to a stunning view of the back end of Tucson’s Catalina mountains, framed by small town activity, remnants of rainfall, and a portentous sky. I squeezed off a few shots straight out of the windshield and got what I call the “essence” exposure I needed. That single image was relatively well-balanced, but it wouldn’t show the full range of textures from the stormy sky and the mountains. Later, in post, I duplicated the one keeper frame that I got, modifying it in Photomatix, my HDR processing program. Adding underexposure, deeper contrast, and a slight rolloff of highlights on the dupe, I processed it with the original shot to get a composite that accentuated the texture of the clouds, the stone,, even the local foliage. A sheer “wild” shot had given me something that I would have totally missed if the car’s GPS had actually taken us to our “correct” destination.

What was ironic was that, once we got where we were going, most of the “intentional” images that I sweat bullets working on were lackluster, compared to the one I shot by the seat of my pants. Hey, we’ve all been there.

Maybe I should get lost more often.

Actually, people have been suggesting that to me for years.

Especially when I whip out a camera.

Related articles

STRING THEORY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CERTAIN INANIMATE OBJECTS INTERACT WITH THE LIVING TO SUCH A LARGE DEGREE, that, to me, they retain a certain store of energy

even when standing alone. Things that act in the “co-creation” of events or art somehow radiate the echo of the persons who touched them.

Musical instruments, for my mind’s eye, fairly glow with this force, and, as such, are irresistable as still life subjects, since, literally, there is still life emanating from them.

Staging the object just outside the reach of full light helped the violin sort of sculpt itself. 1/800 sec., f/2.5, ISO 100, 35mm prime lens.

A while back I learned that my wife had, for years, held onto a violin once used for the instruction of one of her children. I was eager to examine and photograph it, not because it represented any kind of technical challenge, but because there were so many choices of things to look at in its contours and details. There are many “sites” along various parts of a violin where creation surges forth, and I was eager to see what my choices would look like. Also, given the golden color of the wood, I knew that one of our house’s “super windows”, which admit midday light that is soft and diffused, would lend a warmth to the violin that flash or constant lighting could never do.

Everything in the shoot was done with an f/1.8 35mm prime lens, which is fast enough to illuminate details in mixed light and allows for selectively shallow depth of field where I felt it was useful. Therefore I could shoot in full window light, or, as in the image on the left, pull the violin partly into shadow to force attention on select details.

Although in the topmost image I indulged the regular urge to “tell a story” with a few arbitrary

props, I was eventually more satisfied with close-ups around the body of the violin itself, and, in one case, on the bow. Sometimes you get more by going for less.

One thing is certain: some objects can be captured in a single frame, while others kind of tumble over in your mind, inviting you to revisit, re-imagine, or more widely apprehend everything they have to give the camera. In the case of musical instruments, I find myself returning to the scene of the crime again and again.

They are singing their songs to me, and perhaps over time, I quiet my mind enough to hear them.

And perhaps learn them.

LET THERE BE (MORE) LIGHT

A new piece of glass makes everything look better….even another piece of glass. First day with my new 35mm prime lens, wide open at f/1.8, 1/160 sec., ISO 100.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE RECENTLY BEEN EXPERIENCING ONE OF THOSE TIME MACHINE MOMENTS in which I am, again, right back at the beginning of my life as a photographer, aglow with enthusiasm, ripe with innocence, suffused by a feeling that anything can be done with my little black box. This is an intoxication that I call: new lens.

Without fail, every fresh hunk of glass I have ever purchased has produced the same giddy wonder, the same feeling of artistic invincibility. This time out, the toy in question is a Nikon f/1.8 35mm prime lens, and, boy howdy, does this baby perform. For cropped sensor cameras, it “sees” about like the 50mms of old, so its view is almost exactly as the human eye sees, without exaggerated perspective or angular distortion. Like the 50, it is simple, fast, and sharp. Unlike the 50, it doesn’t force me to do as much backing up to get a comfortable framing on people or near objects. The 35 feels a little “roomier”, as if there are a few extra inches of breathing space around my portrait subjects. Also, the focal field of view, even wide open, is fairly wide, so I can get most of your face tack sharp, instead of just an eye and a half. Matter of preference.

All this has made me marvel anew at how fast many of us are generally approaching the age of flashless photography. It’s been a long journey, but soon, outside the realm of formal studio work, where light needs to be deliberately boosted or manipulated, increasingly thirsty lenses and sensors will make available light our willing slave to a greater degree than ever before. For me, a person who believes that flash can create as many problems as it solves, and that it nearly always amounts to a compromise of what I see in my mind, that is good news indeed.

It also makes me think of the first technical efforts to illuminate the dark, such as the camera you see off to the left. The Ermanox, introduced by the German manufacturer Ernemann in 1924, was one of the first big steps in the quest to free humankind of the bulk, unreliability and outright danger of early flash. Its cigarette-pack-sized body was dwarfed by its enormous lens, which, with a focal length of f/2, was speedy enough (1/1000 max shutter) to allow sharp, fast photography in nearly any light. It lost a few points for still being based on the use of (small) glass plates instead of roll film, but it almost single-handedly turned the average man into a stealth shooter, in that you didn’t have to pop in hefting a lotta luggage, as if to scream “HEY, THE PHOTOGRAPHER IS HERE!!” In fact, in the ’20’s and ’30’s, the brilliant amateur shooter Erich Solomon made something of a specialty out of sneaking himself and his tiny Ermanox into high-level government summits and snapping the inner circle at its unguarded best (or worst). Long exposures and blinding flash powders were no longer part of the equation. Candid photography had crawled out of its high chair… and onto the street.

Today or yesterday, this is about more than just technical advancement. The unspoken classism of photography has always been: people with money get great cameras; people without money can make do. Sure, early breakthroughs like the Ermanox made it possible for anyone to take great low-light shots, but at $190.65 in 1920’s dollars, it wasn’t going to be used at most folks’ family picnics. Now, however, that is changing. The walls between “high end” and “entry level” are dissolving. More technical democracy is creeping into the marketplace everyday, and being able to harness available light affordably is a big part of leveling the playing field.

So, lots more of us can feel like a kid with a new toy, er, lens.

Related articles

- Prime Lenses (nikonusa.com)

- Understanding Focal Length (nikonusa.com)

I SEE YOUR FACE BEFORE ME

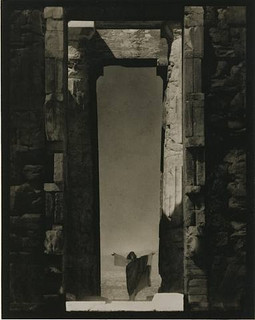

Edward Steichen’s amazing 1921 portrait of dance icon Isadora Duncan beneath a massive arch of the Parthenon in Greece, an image which recently surged to the top of my mind. See a link to a larger view of this shot, below.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE IMAGES SIT AT THE BOTTOM OF THE BRAIN, LIKE STONE PILLARS IN THE FOUNDATION OF AN IMMENSE TOWER.The structures erected on top of them, those images we ourselves have fashioned in memory of these foundations, dictate the height and breadth of our own creative edifices. Between these elemental pictures and what we build on top of them, we derive a visual style of our own.

In my own case,many of the pillars that hold up my own house of photography come from a single man.

Edward Steichen is arguably the greatest photographer in history. If that seems like hyperbole, I would humbly suggest that you take a reasonable period of time, say, oh, twenty years or so, just to lightly skim the breadth of his amazing career….from revealing portraits to iconic product shots to nature photography to street journalism and half a dozen other key areas that comprise our collective craft of light writing. His work spans the distance from wet glass plates to color film, from the Edwardian era to the 1960’s, from photography as an insecure imitation of painting to its arrival as a distinct and unique art form in its own right.

At the start of the 20th century, Steichen co-sponsored many of the world’s first formal photographic galleries, and was a major contributor to Camera Work, the first serious magazine dedicated wholly to photography. He ended his career as the creator of the legendary Family Of Man, created in the early 1950’s and still the most celebrated collection of global images ever mounted anywhere on earth. He is, simply, the Moses of photography, towering above many lesser giants whose best work amounts to only a fraction of his own prodigious output.

Which is why I sometimes see fragments of what he saw when I view a subject. I can’t see with his clarity, but through the milky lens of my own vision I sometime detect a flashing speck of what he knew on a much larger scale, decades before. The image at left recently rocketed to my mind’s eye several weeks ago, as I was framing shots inside a large government building in Ohio.In 1921, Steichen journeyed to Greece to use the world’s oldest civilization basically as a prop for portraits of Isadora Duncan, then in the forefront of American avant-garde dance. Framing her at the bottom of an immense arch in the ruins of the Parthenon, he made her appear majestic and minute at the same time, both minimized and deified by the huge proportions in the frame. It is one of the most beautiful compositions I have ever seen, and I urge you to click the Flickr link at the end of this post for a slightly larger view of it. (Also note the link to a great overview of Steichen’s life on Wikipedia.)

Uplighting creates a moody frame-within-frame feel at the Ohio Statehouse building, in a shot inspired by Edward Steichen’s images of massive arches. 1/30 sec., f/8, ISO 800, 18mm.

In framing a similarly tall arch leading into the rotunda of the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus, I didn’t have a human figure to work with, but I wanted to show the building as a series of major and minor access cavities, in, around, under and through one of its arched entrance to the central lobby. I kept having to back up and step down to get at least a partial view of the rotunda and the arch at the opposite end of the open space included in the frame, which created a kind of left and right bracket for the shot, now flanked by a pair of staircases. Given the overcast sky meekly leaking grey light into the rotunda’s glass cupola, most of the building was shrouded in shadow, so a handheld shot with sufficient depth of field was going to call for jacked-up ISO, and the attendant grungy texture that remains in the darker parts of the shot. But at least I walked away with something.

What kind of something? There is no”object” to the image, no story being told, and sadly, no dancing muse to immortalize. Just an arrangement of color and shape that hit me in some kind of emotional way. That and Steichen, that foundational pillar, calling up to me from the basement:

“Just take the shot.”

Related articles

- The Photograph as a Social Statement (halsmith.wordpress.com)

- Picture Imperfect (andrewsullivan.thedailybeast.com)

- http://www.flickr.com/photos/quelitab/5793648357/lightbox/

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Steichen

TURNING UP THE MAGIC

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CHRISTMAS IS SO BIG THAT IT CAN AFFORD TO GO SMALL. Photographers can, of course, tackle the huge themes….cavernous rooms bursting with gifts, sprawling trees crowning massive plazas, the lengthy curve and contour of snowy lanes and rustic rinks…..there are plenty of vistas of, well, plenty. However, to get to human scale on this most superhuman of experiences, you have to shrink the frame, tighten the focus to intimate details, go to the tiny core of emotion and memory. Those things are measured in inches, in the minute wonder of things that bear the names little, miniature, precious.

And, as in every other aspect of holiday photography, light, and its successful manipulation, seals the deal.

A proud regiment of nutcrackers, made a little more enchanting by turning off the room light and relying on tiny twinklers. 1/2 sec., f/4, ISO 100, 20mm

In recent years I have turned away from big rooms and large tableaux for the small stories that emanate from close examination of corners and crannies. The special ornament. The tiny keepsake. The magic that reveals itself only after we slow down, quiet down, and zoom in. In effect, you have to get close enough to read the “Rosebud” on the sled.

Through one life path and another, I have not been “home” (that is, my parents’ home) for Christmas for many years now. This year, I broke the pattern to visit early in December, where the airfare was affordable, the overall scene was less hectic and the look of the season was visually quiet, if no less personal. It became, for me, a way to ease back into the holidays as an experience that I’d laid aside for a long time.

A measured re-entry.

I wanted to eschew big rooms and super-sized layouts to concentrate on things within things, parts of the scene. That also went for the light, which needed to be simpler, smaller, just enough. Two things in my parents’ house drew me in: several select branches of the family tree, and one small part of my mother’s amazing collection of nutcrackers. In both cases, I had tried to shoot in both daylight and general night-time room light. In both cases, I needed some elusive tool for enhancement of detail, some way to highlight texture on a very muted scale.

Call it turning up the magic.

Use of low-power, local light instead of general room ambience enhances detail in tiny objects, revealing their textures. 1/2 sec., f/4, ISO 100, 20mm.

As it turned out, both subjects were flanked by white mini-lights, the tree lit exclusively by white, the nutcrackers assembled on a bed of green with the lights woven into the greenery. The short-throw range of these lights was going to be all I would need, or want. All that was required was to set up on a tripod so that exposures of anywhere from one to three seconds would coax color bounces and delicate shadows out of the darkness, as well as keeping ISO to an absolute minimum. In the case of the nutcrackers, the varnished finish of many of the figures, in this process, would shine like porcelain. For many of the tree ornaments, the looks of wood, foil, glitter, and fabric were magnified by the close-at-hand, mild light. Controlled exposures also kept the lights from “burning in” and washing out as well, so there was really no down side to using them exclusively.

Best thing? Whole project, from start to finish, took mere minutes, with dozens of shots and editing choices yielded before anyone else in the room could miss me.

And, since I’d been away for a while, that, along with starting a new tradition of seeing, was a good thing.

Ho.

Related articles

- How to Take a Picture of Your Christmas Tree (purdueavenue.com)

ONE LESS MESS TO SWEAT

Lefty O’Doul’s bar, near Union Square in San Francisco. Lovely place, great grub, but a dark cavern where light goes to die. Modern DSLRs allow this to be a handheld shot with a minimum of noise: 1/20 sec., 5/5, ISO 640, 18mm.

by MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY TIME I READ SINCERE ARGUMENTS FOR THE SUPERIORITY OF FILM OVER DIGITAL, the debate seems a little more lopsided on the side of sentiment than on the side of reason. The whole thing can make me a little….tired. As I write this, Arizona Highways has just released its annual collection of the fifty best images ever published in that august standard of print photography, and, yep, you guessed it, only about the last three images are digital. It’s an aesthetic bias which AH will only abandon once the entire rest of the world regards film as a quaint artifact of The Good Ole Days, but, God bless ’em, they are true believers. As for myself, I am in no huge hurry to see film go the way of the Hostess Twinkie. However, I do readily admit that it’s my heart casting that vote, and not my head.

Emulsions or pixels? Your preference still comes down to what you need to do and how you need to do it. That means that many of us will choose one medium or the other because it either enables or constricts our art…..in other words, a simply practical judgement, not one based on our fondness for what we are used to. Earlier this year, I applauded National Public Radio’s commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the battle of Antietam (one of the first Civil War skirmishes to be photographically documented), by commissioning their own photog to shoot some of the same battle sites as Alexander Gardner had done in 1862, using the same kind of coated glass plate process. Were the results fascinating? Certainly. Are they likely to create a run on camera stores for collodion? Don’t hold your breath.

Photography is a constant process of knocking down more obstacles between what you are shooting at and the imagination you are shooting with. You need to keep the camera from fighting you, due to its inability to react, think, discriminate or judge the way that only you can. To that end, you have to be in a constant flow of improvement, simply because your mind is always traveling on a faster track than even the best camera, and that instrument must be corralled into helping, and not hindering, the task of getting your vision into that box.

One of the most helpful such advances for me has been the accelerated performance of DSLRs in low-light situations and the improvement in picture quality at increasingly higher ISO settings. In the film world of “ago”, if you wanted to shoot at 800 speed ASA, you had to have a camera loaded with 800 speed film. If you then, five minutes later, wanted to shoot at 100 speed ASA you would need to reload your camera with that speed of film, or have a whole separate camera that was loaded with it. And so on.

Not the best for flexibility. Or spontaneity.

Pellegrino’s Restaurant, Little Italy, New York City. Handheld. Street photography gets an amazing boost from cameras that feed on low light. 1/50 sec., f/5.6, ISO 640, 18mm.

This rocketing forward of the technology that gives us sharp, nearly noise-free pictures, handheld and at fast exposure times, in all but the most hopeless lighting scenarios, is now filtering down to even the most rudimentary camera phones.It’s not alarmist or false to declare that the days of the compact point-and-shoot are officially numbered. With ISO now delivering better results in so many shooting situations, I can now go nearly anywhere and have a shot at getting a shot. That puts me at a distinct advantage over the most proficient shooters and the best cameras of barely a generation ago.

Does that guarantee I’ll bring back a winner? Nope. But the point is, more and more, if I don’t get the shot, it’s on me. I can’t blame my failure on balky technology, at least not in this particular case.

And it means I can spend more time shooting, dreaming, doing, instead of crossing my fingers and hoping.

Related articles

- Camera+ 3.6 is here: “It’s a camera, not a flight simulator!” (taptaptap.com)

- Is a DSLR right for you? (fatwallet.com)

LOOK THROUGH ANY WINDOW, PART TWO

By MICHAEL PERKINS

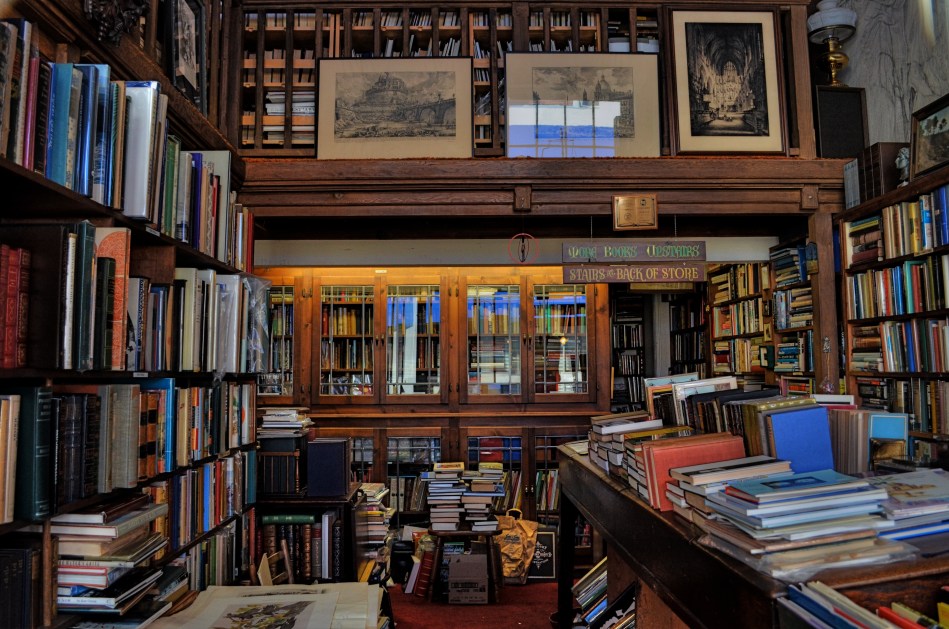

I WILL DO ANYTHING TO PHOTOGRAPH BOOKSTORES. Not the generic Costco and Wal-Mart bargain slabs laden with discounted bestsellers. Not the starched and sterile faux-library air of Barnes & Noble. I’m talking musty, dusty, crammed, chaotic collections of mismatched, timeless tomes…. “many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore” as Poe labeled them. I’m looking for places run by dotty old men with their glasses high on their forehead, cultural salvage yards layered in multiple stories of seemingly unrelated offerings in random stacks and precarious piles. Something doomed by progress, and beautiful in its fragility.

I almost missed this one.

Through the window, and into a forgotten world. A fake two-shot HDR from a single exposure at 1/80 sec., f/5, ISO 400, 18mm.

In my last post, I commented that, even when your photography is rules-based….i.e., always do this, never do that, there are times when you have to shoot on impulse alone and get what you can get. It sometimes begins when you’re presented with something you’re not, but should be, looking for. A few weeks ago, I was spending the afternoon at one of Monterey, California‘s most time-honored weekly rituals..the marvelous, multi-block farmers’ market along Alvarado Street. The sheer number of vendors dictates that some of the booths spill over onto the side streets, and that’s where I found The Book Haven. The interior of the store afforded an all-in-one view of its entire sprawling inventory, but the crush of tourists bustling in and out of its teeny front door meant that any image was going to look like the casting call for The Ten Commandments.

I had to come back, when both the store and I were alone.

With the limited amount of time I had in town, that meant that I would have to stroll by just hours ahead of my plane for home. Heading out at 8:30 in the morning, I had obviously solved the problem of “too many people in the picture”, but I had traded that hassle for a new one: the store would not be open for another three hours.

For the second time in a week (see “Look Through Any Window, Part One”) I was forced to shoot through a window, but at least there was enough light inside to illuminate nearly all of the store’s interior. To avoid a reflection, I would have to cram my lens right up against the glass. Once my autofocus stopped fidgeting, I could only obtain the framing I wanted by shooting through a narrow open place on the center of the front door, standing on tiptoe to hold the composition. I also had to keep the ISO dialed low enough to not create extra noise, but high enough so I could take a fairly fast handheld exposure and get as much detail from the dark corners as possible. Balancing act.

Let’s see what happens.

In viewing the image later, I saw that there wasn’t enough detail to suit me, either in the individual books or the darker spaces around the store, so I pulled a small cheat. Making a copy of the shot, I pulled down the contrast, boosted the exposure, and sucked out some shadow, then loaded both shots into Photomatix, fooling the HDR program into thinking they were two separate exposures. Photomatix is also a detail enhancer program, so I could add sharper textures to the books and a richer range of tones than were seen in the original through-the-window shot.

Hey, you can’t have it all, but, by at least trying, you get more than nothing.

And sometimes that’s everything.

Nice bookstore.

LOOK THROUGH ANY WINDOW, PART ONE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE COMMON THREAD ACROSS ALL THE PHOTO HOW-TO BOOKS EVER WRITTEN IS A WARNING: don’t let all the rules we are discussing here keep you from making a picture. Standardized techniques for exposure, composition, angle, and processing are road maps, not the Ten Commandments. It will become obvious pretty quickly to anyone who makes even a limited study of photography that some of the greatest pictures ever taken color outside the classical lines of “good picture making.” The war photo that captures the moment of death in a blur. The candid that cuts off half the subject’s face. The sunset with blown-out skies or lens flares. Many images outside the realm of “perfection” deliver something immediate and legitimate that goes beyond mere precision. Call it a fist to the gut.

The dawn creeps slowly in on the downtown streets of Monterey, California. A go-for-broke window shot taken under decidedly compromised conditions. 1/15 sec., f/3.5, ISO 640, 18mm.

Conversely, many technically pristine images are absolutely devoid of emotional impact, perfect executions that arrive at the finish line minus a soul. Finally, being happy with our results, despite how far they are from flawless is the animating spirit of art, and feeling. This all starts out with a boost of science, but it ain’t really science at all, is it? If it were, we could just send the camera out by itself, a heart-dead recording instrument like the Mars lander, and remove ourself from the equation entirely.

Thus the common entreaty in every instruction book: shoot it anyway. The only picture that is sure not to “come out” is the one you don’t shoot.

The image at left, of a business building in downtown Monterey, California was almost not taken. If I had been governed only by general how-to rules, I would have simply decided that it was impossible. Lots of reasons “not to”; shooting from a high hotel window at an angle that was nearly guaranteed to pick up a reflection, even taken in a dark room at pre-dawn; the need to be too close to the window to mount a tripod, therefore nixing the chance at a time exposure; and the likelihood that, for a hand-held shot, I would have to jack the camera’s ISO so high that some of the darker parts of the building would be the smudgy consistency of wet ashes.

Still, I couldn’t walk away from it. Mood, energy, atmosphere, something told me to just shoot it anyway.

I didn’t get “perfection”. That particular ideal had been yanked out of my reach, like Lucy pulling away Charlie Brown’s football. But I am glad I tried. (Click on the image to see a more detailed version of the result)

In the next post, a look at another window that threatened to hold a shot hostage, and a solution that rescued it.

Related articles

- 7 Ways to Inject More Creativity Into Your Photos (blogworld.com)

BEAUTIFUL LOSERS

Shooting on the street is bound to give you mixed results. I have been messing with this shot of a Brooklyn coffee shop for days, and I still can’t decide if I like it. 1/80 sec., f/5, ISO 100, 24mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE A LOT OF INSTANTANEOUS “KEEP” OR “LOSE” CALLS that are made each day when first we review a new batch of photos. Which to cherish and share, which to delete and try to forget? Thumbs up, thumbs down, Ebert or Roper. Trash or treasure. Simple, right?

Only, the more care we take with our shooting, the fewer the certainties, those shots that are immediately clear as either hits or misses. As our experience grows, many, many more pictures fall into the “further consideration” pile. Processing and tweaking might move some of them into the “keep” zone, but mostly, they haunt us, as we view, re-view and re-think them. Even some of the “losers” have a sort of beauty, perhaps for what they might have been rather than what they turned out to be. It’s like having a kid that you know will always be “C” average, but who will never stop reaching for the “A”, God love their heart.

I have thousands of such pictures now,pictures that I study, weep over, slap my forehead about, ask “what was I thinking?” about. I never have been one for doing a reflexive jab on the “delete” button as I shoot, as I believe that the near misses, even more than the outright disasters, teach us more than even the few lucky aces. So I wait at least to see what the shot really looks like beyond the soft deception of the camera monitor. I buy the image at least that much time, to really, really make sure I dropped a creative stitch.

Many times my initial revulsion was correct, and the shot is beyond redemption.

Ah, but those other times, those nagging, guilt-laden re-thinks, during which I get to twist in the wind a little longer. Pretty? Ugly? Genius? Jerk? Just like waiting for an old Polaroid to gradually fade in, so too, the ultimate success or failure of some pictures takes a while to emerge. And even then, well, let’s come back and look at this one later…….

The above frame, taken while I was walking toward the pedestrian ramp to the Brooklyn Bridge, is just such a shot. My wife stepped into a coffee shop just fast enough to grab us some bottled water, while I waited on the sidewalk trying to make my mind up whether I had anything to shoot. As you can see, what I got could be legitimately called a fiasco. Nice color on the store’s neon sign, and a little “slice of life” with the customer checking out at the register, but then it all starts to mush into a hot mess, with the building and car across the street eating up so much of the front window that your eye is dragged all over the place trying to answer the musical question, “what are we doing here?” Storefront shots are a real crap shoot. That is, sometimes you have something to shoot, and sometimes you just have crap.

Even at this point, with more than a few people giving the shot a thumbs-up online, I can’t be sure if I just captured something honest and genuine, or if I’ve been reading too many pointy-headed essays on “art” and have talked myself into accepting a goose egg as something noble.

But as I said at the top of this piece, the choices get harder the more kinds of stuff you try. If you shoot your entire life on automode, you don’t have as many shots that almost break your heart. I wonder what my personal record is for how long after the fact I’ve allowed myself to grieve over the shots that got away. It’s tempting to hit that delete button like a trigger-happy monkey and just move on.

But, finally, the “almosts” show you something, even if they just stand as examples of how to blow it.

And that is sometimes enough to make the losers a little bit beautiful.

Thoughts?

MAKE SOMETHING UP

Table-top romance gone wrong. Plastic Frank runs out on his clingy and equally plastic girlfriend. Shot on a tripod in darkness and light-painted with hand-held LED. 15 sec., 5/4.5, 30mm and, most importantly, since it’s a time exposure, stay at ISO 100. You’ll have plenty of light and keep the noise to a minimum.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS ONE PARTICULAR AREA WHERE, ALL AESTHETIC DEBATES ASIDE, DIGITAL BEATS FILM COLD. That, of course, is in the area of instantaneous feedback, the flexibility afforded to the shooter of adjusting his approach to a project “on the fly”. Simply stated, the shoot-check-adjust-shoot again workflow permitted by digital simply has to prevent more blown shoots and wasted opportunities than film. Shooting a tricky or rapidly changing subject with film can be honed to a pretty sure science, to be sure, especially given years of practice and a keenly trained eye on the part of the person behind the lens. However, a sizable gap of luck, or well-placed guesses remains, a gap narrowed by digital’s ability to speedily provide creative feedback. Release the hounds on me if this makes me a heretic, but as a lover of film, I still prefer the choices digital presents. I don’t have to hate horses to love automobiles.

The digital edge comes through to me especially in table-top shoots executed in darkness and illuminated with selectively “painted” light. I have already written on the general technique I use for these very strange projects in a post called Hello Darkness My Old Friend, so I won’t elaborate on that part again. What I will re-emphasize is that these kind of shots can only be arrived at through a lot of negative feedback, since hand-applied light sources produce drastically different results with every “pass” of the LED, or whatever your source of illumination may be. It’s also hard to find a shot that you love so much that you stop tweaking the process. The next shot just may afford you the quick flick of the wrist that will dramatically shift or redistribute shadows or re-jigger the highlighting of a surface feature.

Tends to fill up those rainy afternoons in a jiffy.

For the above image, I rescued two old dolls from the ash can for one more chance at fame. A friend who knew I was a lifelong Sinatra fan gifted me years ago with a beautifully detailed figure of Ol’ Blue Eyes in his trademark fedora and trench coat, the perfect get-up for hanging out underneath lonely, dim streetlights after all the bars have closed. The other figure is of course a Barbie, left behind when my stepdaughter headed off for college. Normally, these two characters wouldn’t exist in the same universe, and that was what struck me as fun to fool around with. I started to see Barbs as just one of a series of romantic conquests by The Voice on his way through the Universe of Total Coolness, with the inevitable bust-up happening on a dark street in the wee small hours of the morning.

For this shot, the idea was to light just enough of Frankie from above to suggest the aforementioned street lamp, accentuating the textures in his costume and the major angles of his face, without making his head glow so much as to underscore the fact that, duh, it’s made of plastic. The old Barbie had major hairdo issues, but hey, that’s why God made shallow focus. What I got wasn’t perfect, but then, it never is. The important thing with these projects is to make something up and make something come alive, to some degree.

Sadly, Barbie was probably the best thing that ever happened to the Chairman, something he’ll no doubt realize further down that long, lonesome road, looking for answers at the bottle of a shot glass. Hey, his loss.

So goodbye, babe and Amen / Here’s hoping we’ll meet now and then / It was great fun / But it was just one of those things…..

Related articles

- Swank or Rank? Frank Sinatra’s Former Penthouse Hits the Market for $7.7 M. (observer.com)

- tips for fun “everyday” photos. (eliseblaha.typepad.com)

- Hello Darkness My Old Friend (thenormaleye.com)

TRAVEL JITTERS

“Autumn in New York, why does it seem so inviting?” A shot inside Central Park, November 2011. 1/60 sec., f/5.6, ISO 160, 50mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF THERE IS SUCH A THING AS PHOTOGRAPHIC STAGE FRIGHT, it most likely is that vaguely apprehensive feeling that kicks in just before you connect with a potentially powerful subject. And when that subject is really Subject One, i.e., New York City, well, even a pro can be forgiven a few butterflies. They ain’t kidding when they sing, if I can make it there I can make it anywhere. But, of course, the Apple is anything but anywhere…….

Theoretically, if “there are eight million stories in the Naked City”, you’d think a photographer would be just fine selecting any one of them, since there is no one single way of representing the planet’s most diverse urban enclave. And there are over 150 years of amazing image-making to support the idea that every way of taking in this immense subject is fair territory.

And yet.

And yet we are drawn (at least I am) to at least weigh in on the most obvious elements of this broad canvas. The hot button attractions. The “to-do list” locations. No, it isn’t as if the world needs one more picture of Ellis Island or the Brooklyn Bridge, and it isn’t likely that I will be one of the lucky few who will manage to bring anything fresh to these icons of American experience. In fact, the odds are stacked horribly in the opposite direction. It is far safer to predict that every angle or framing I will try will be a precise clone of millions of other visualizations of almost exactly the same quality. Even so, with every new trip to NYC I have to wean myself away from trying to create the ultimate postcard,to focus upon one of the other 7,999,999 stories in the city. Even at this late date, there are stories in the nooks and crannies of the city that are largely undertold. They aren’t as seductive as the obvious choices, but they may afford greater rewards, in that there may be something there that I can claim, that I can personally mine from the rock.

By the time this post is published, I will be taking yet another run at this majestic city and anything additional in the way of stories that I can pry loose from her streets. Right now, staring at this computer, nothing has begun, and everything is possible. That is both exhilarating and terrifying. The way to banish the travel jitters is to get there, and get going. And yes, I will bring back my share of cliches, or attempts at escaping them. But, just like a stowaway on a ship arriving in the New World, something else may smuggle itself on board.

I have to visit my old girlfriend again, even if we wind up agreeing to be just friends.

And, as all photographers (and lovers) do, I hope it will lead to something more serious.

Thoughts?

HELLO DARKNESS MY OLD FRIEND

This still life, designed to recall the “cold war” feel of the tape recorder and other props, was shot in a completely darkened room, and lit with sweeps and stabs of light from a handheld LED, used to selectively create the patterns of bright spots and shadows. Taken at 19 seconds, f/6.3, ISO 100 at 50mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MOST OF THE PICTURES WE TAKE involve shaping and selecting details from subjects that are already bathed, to some degree, in light. “Darkness” is in such images, but it resides peripherally in the nooks and crannies where the light didn’t naturally flow or was prevented from going. Dark is thus the fat that marbles the meat, the characterizing texture in a generally bright palette of colors. It is seasoning, not substance.

By contrast, shooting that begins in total darkness means entering a realm of mystery, since you start with nothing, a blank and black slate, onto which you selectively import some light, not enough to banish the dark, but light that suggests, implies, hints at definition. For the viewer, it is the difference between the bright window light of a chat at a mid-afternoon cafe and the intimacy of a shared huddle around a midnight campfire. What I call “absolute night” shots are often more personal work than just managing to snap a well-lit public night spot like an urban street or an illuminated monument after dusk. It’s teaching yourself to show the minimum, to employ just enough light to the tell the story, and no more. It is about deciding to leave out things. It is an editorial, rather than a reportorial process.

The only constants about “absolute dark” shooting are these:

You need a tripod-mounted camera. Your shutter will be open as long as it takes to create what you want, and far longer than you can hope to hold the camera steady. If you have a timer and/or a remote shutter release, break those out of the bag, too. The less you touch that camera, the better. Besides, you’ll be busy with other things.

Set the minimum ISO. If you’re quickly snapping a dark subject, you can compromise quality with a higher and thus slightly noisier ISO setting. When you have all the time you need to slowly expose your subject, however, you can keep ISO at 100 and banish most of that grain. Some cameras will develop wild or “hot” pixels once the shutter’s open for more than a minute, but for many hand-illuminated dark shots, you can get what you need in far less than that amount of time.

Use some kind of small hand-held illumination. Something about the size of a keychain-sized LED, with an extremely narrow focus of very white light. Pick them up at the dollar store and get a model that works well in your hand. This is your magic wand, with which, after beginning the exposure in complete darkness, you will be painting light onto various parts of your subject, depending on what kind of effect you want. Get a light with a handy and responsive power switch, since you may turn the light on and off many times during a single exposure.

You can use autofocus, even in manual mode, but compose and lock the focus when all the room lights are on. Set it, forget it, douse the power and get to work.

Which brings us to an important caveat. Even though you are avoiding the absolute blast-out of white that would result if you were using a conventional flash, lingering over a particular contour of your subject for more than a second or so will really burn a hot spot into its surface, perhaps blowing out an entire portion of the shot. Best way to curb this is to click on, paint, click off, re-position, click back on and repeat the sequence as needed. Another method could involve making slow but steady passes over the subject….back and forth, imagining in your mind what you want to see lit and what you want to remain dark. It’s your project and your mood, so you’ll want to shoot lots of frames and pause between each exposure to adjust what you’re doing, again based on what kind of look you’re going for.

Beyond that, there are no rules, and, over the course of a long shoot, you will probably change your mind as to what your destination is anyhow. No one is getting a grade on this, and the results aren’t going in your permanent file, so have fun with it.

Also shot in a darkened room, but with simpler lighting plan and a shorter exposure time. The dial created its own glow and a handheld light gave some detail to the grillwork. 1/2 sec., 5/4.8, ISO 100, 32mm.

Some objects lend themselves to absolute night than others. For example, I am part of the last generation that often listened to radio in the dark. You just won’t get the same eerie thrill listening to The Shadow or Inner Sanctum in a gaily lit room, so, for the above image of my mid-1930’s I.T.I. radio, I wanted a somber mood. I decided to make the tuning dial’s “spook light” my primary source of interest, with a selective wash of hand-held light on the speaker grille, since the dial was too weak (even with a longer exposure) to throw a glow onto the rest of the radio’s face. Knobs are less cool so they are darker, and the overall chassis is far less cool, so it generally resides in shadow. Result: one ooky-spooky radio. Add murder mystery and stir well.

Flickr and other online photo-sharing sites can give you a lot of examples on what subjects really come alive in the dark. The most intoxicating part of point-and-paint lighting is the sheer control you have over the process, which, with practice, is virtually absolute. Control freaks of the world rejoice.

Head for the heart of darkness. You’ll be amazed what you can see, or, better yet, what you can enable others to see.

Thoughts?

NOTE: If you wish to see comments on this essay, click on the title at the top of the article and they should be viewable after the end of the post.

Related articles

- Lighting Techniques: Light Painting (nikonusa.com)

- Light Writing (cutoutandkeep.net)

SPLITTING THE DIFFERENCE

Really dark church, not much time. An HDR composite of just two exposures to refrain from trying to read the darkest areas and thus keep extra noise out of the final image. Shot at 1/15 and 1/30 sec., both exposures at f/5.6, a slight ISO bump to 200 at 18mm. Far from perfect but something less than a total disaster with an impatient tour group wondering where I wandered off to.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE MOST EXASPERATING WORDS HEARD ON VACATION: Everyone back on the tour bus.

Damn. Okay, just a second.

Now. We’re going NOW.

I’ve almost got it (maybe a different f-stop….? …..no, I’m just standing in my own light….here, let’s try THIS….

I mean it, we’re leaving without you.

YES, right there, seriously, I’m right behind you. Read a brochure will ya? Geez, NOTHING’S working…….

Sound remotely familiar? There seems to be an inverse proportion of need-to-result that happens when an entire group of tourists is cursing your name and the day you ever set eyes on a camera. The more they tap their collective toe wondering what’s taking so looooong, the farther you are away from anything that will, even for an instant, give you a way to get on that bus with a smile on your face. It’s like the boulder is already bearing down on Indiana Jones, and, even as he runs for his life, he still wonders if there’d be a way to go back for just one more necklace….

Dirty Little Secret: there is no such thing as a photo “stop” when you are part of a traveling group. At best it’s a photo “slow down” unless you literally want to shoot from the hip and hope for the best, which doesn’t work in skeet shooting, horseshoes, brain surgery, ….or photography. Dirty Little Secret Two: you are only marginally welcome at the tomb or cathedral or historically awesome whosis they’re dragging you past, so be grateful we’re letting you in here at all and don’t go all Avedon on us. We know how to handle people like you. We’re taking the next delay out of your bathroom break, wise guy.

A recent trip to the beautiful Memorial Church at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California was that latest of many “back on the bus” scenarios in my life, albeit one with a somewhat happy outcome. Dedicated in 1903 by the surviving widow of the school’s founder, Leland Stanford, the church loads the eye with borrowed styles and decorous detail from a half-dozen different architectural periods, and yet, is majestic rather than noisy, a tranquil oasis within a starkly contemporary and busy campus. And, within seconds of having entered its cavernous space as part of a walking campus tour, it becomes obvious that it will be impossible to do anything, image-wise, other than selecting a small part of the story and working against the clock to make a fast (prayerful) grab. No tripods, no careful contemplation; this will be meatball surgery. And the clock is ticking now.

So we ducked inside. With many of the church’s altars and alcoves shrouded in deep shadow, even at midday, choices were going to be limited. A straight-on flash was going to be an obscene waste of time, unless I wanted to see a blown-out glob of white, three feet in front of me, the effect of lighting a flare in a cave. Likewise, bumping my Nikon’s ISO high enough to read a greater amount of detail was going to be a no-score, since the inner darkness was so stark, away from the skylight of the central basilica dome, that I was inviting enough noise to make the whole thing look like a kid’s smudged watercolor. No, I had to find a way to split the difference; Show some of the light and let the darkness alone.

Instead of bracketing anywhere from 3 to 5 shots in hopes of creating a composite high dynamic range image in post production, I took a narrower bracket of two. I jacked the ISO for both of them just a bit, but not enough to get a lethal grunge gumbo once the two were merged. I shot for the bright highlights and tried to compose so that the light’s falloff would suggest the detail I wouldn’t be able to actually show. At least getting a good angle on the basilica’s arches would allow the mind to sketch out the space that couldn’t be adequately lit on the fly. For insurance, I tried the same trick with several other compositions, but by that time my wife was calling my cel from outside the church, wondering if I had fallen into the baptismal font and drowned.

Yes, right there, I’m coming. Oh, are you all waiting for me? Sorry…..

Perhaps its the worst kind of boorish tourism to forget that, when the doors to the world’s special places are opened to you, you are an invited guest, not some battle-hardened newsie on deadline for an editor. I do really want to be nice. However, I really want to go home with a picture,too, and so I remain a work in progress. Perhaps I can be rehabilitated, and, for the sake of my marriage, I should try.

And yet.

Related articles

- The Ultimate Guide to HDR Photography (pixiq.com)

BEYOND THE THING ITSELF

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU NO DOUBT HAVE YOUR OWN “RULES” as to when a humble object becomes a noble one to the camera, that strange transference of energy from ordinary to compelling that allows an image to do more than record the thing itself. A million scattered fragments of daily life have been morphed into, if not art, something more than mundane, and it happens in an altogether mysterious way somewhere between picking it and clicking it. I don’t so much have a list of rules as I do a sequence of instincts. I know when I might have stumbled across something, something that, if poked, prodded or teased out in some way, might give me pleasure on the back end. It’s a little more advanced than a crap shoot and a far cry from science.

With still life subjects, unlike portraits or documentary work. there isn’t an argument about the ethics or “purity” of manipulating the material….rearranging it, changing the emphasis, tweaking the light. In fact, still lifes are the only kinds of pictures where “working it” is the main objective. You know you’re molding the material. You want to see what other qualities or aspects you can reveal by, well, kind of playing with your food. It’s like Richard Dreyfuss shaping mashed potatoes into the Devil’s Tower.

If I have any hard and fast rule about still lifes, it may be to throw out my trash a little slower. I can recall several instances in which I was on my way the garbage can with something, only to save it from oblivion at the last minute, turn it over on a table, and then try to tell myself something new about it from this angle or that. The above image, taken a few months ago, was such a salvage job, and, for reasons only important to myself, I like what resulted. Hey, Rauschenburg glued egg cartons on canvas. This ain’t new.

My wife had packed a quick fruit and nut snack into a piece of aluminum foil, forgot to eat it, and brought it back home in her lunch sack. In cleaning out the sack, I figured she would not want to take it a second day and started to throw it out. Re-wrapped several times, the foil now had a refractive quality which, in conjunction with window light from our patio, seemed to amp up the color of the apple slice and the almonds. Better yet, by playing with the crinkle factor of the foil, I could turn it into a combination reflector pan and bounce card. Five or six shots worth of work, and suddenly the afternoon seemed worthwhile.

I know, nuts.

Fruits and nuts, to be exact. Hey, if we don’t play, how will we learn to work? Get out on the playground. Make the playground.

And inspect your trash as you roll it to the curb.

Hey, you never know.

Thoughts?

GOING FOR BROKE

Some people are over the whole “art” thing. Certainly this cynical fellow has seen it all. I used a primitive flash bounce to illuminate his darkened features. 1/40 sec., f/5, ISO 500, 22mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE READ MORE THAN A FEW ARTICLES OF LATE by professional photographers who confess that they occasionally get stuck in teaching mode, even to the detriment of their own love of shooting. One such author went to far as to recall a recent concert he had attended, camera-less, only to observe, with snotty amusement, the attempts of a young woman to capture action on the far-off stage area. His first reaction was to disdain not only her limited camera but to catalogue all her most heinous errors in composition, exposure, and use of flash, as he mentally predicted how poor her results would be and how she was, essentially, wasting her time.

Then something shifted in his thinking. Instead of being depressed at what hadn’t worked, the woman’s energy revealed that she was actually making the most of the moment; learning, through trial and error, what to do or not do in future. At the end of his essay, he came to realize that “she is a better photographer than me”, since she was taking risks, pushing the limits of her own skills, and developing her craft, one frame at a time, while he had left his own camera at home and was learning nothing. His point hit home with me, since it is a recurring theme of this blog and a key belief among those I respect most in the imaging world.

In brief:

Shoot. Shoot some more. Dare to fail. Be willing to take more “bad” pictures than the next guy. Get your head out of academic minutia and into the doing of it. Screw up, suck up, but above all, show up.

Ready to play.

Sometimes, just the sheer unwillingness to go home empty-handed provides you with real delight. Last week, I was making the rounds at an area gallery district, the type that does nightly “art walks” as a way of speed-dating potential customers. Many of the best shots I get in these surroundings are near or just after dark, and I always like peeping into the windows of shuttered businesses at night, since some key character of light and mood invariably occurs. For the shot shown above, I fell in love with one gallery that had a kind of sentry posted outside, in the form of an enormous sculpted head. Its aloof expression reminded me of a cross between Easter Island and Blue Man Group, and I really wanted him/her/it to be a part of the shot. However, I had not brought an external flash unit with me, and the sculpture was reading 100% dark in contrast to the interior of the gallery. I was desperate, but not desperate enough to use straight-on pop-up flash, which would have blown the face out completely and destroyed any chance at a moody feel.

Time to improvise.

Having left my bounce card at home as well (I was on foot and truly traveling light), I noticed that the head was underneath a low over-hanging porch roof, something you just must have on the front of an Arizona business in summer. Going totally into what-the-hell mode, I stuck my flat left hand just under the bottom of the pop-up flash and angled it upward about 15 degrees to create a crude bounce off the roof ceiling, allowing the light to soften as it came down upon the top of the head. It took a few tries to avoid creating an uber-white Aurora Borealis effect on the ceiling, and I had to move my feet around to figure out how to get some of the light to cascade down the head’s front and illuminate its features. I also had to bump the ISO up a bit to compensate for the fall-off in the flash at the distance I was standing, but, at the end, I at least got something. Moreover, like the woman at the concert, what I had picked up in technique more than compensated me for the fact that the shot wasn’t strictly an award winner.

I have been playing around with primitive flash bouncing for a while now, and the results run the gamut from god-awful to glad-I-did-that. But it’s all a win no matter how each individual shot plays out, because every image brings me closer to the cumulatively evolved instinct that, someday, will give me great pictures. The baby will eventually be born, but the midwife has to do the front-end work. Nothing I will ever shoot will be captured under perfect conditions, so why drop dead of old age waiting for that to happen? We’re almost to the end of Century Two in this game of writing with light, and all the easy pictures have already been shot, so what’s left will have to be hewed out by hand.

I suggest that we occasionally get our nose out of books (and, duh, blogs too) and start carving.

180 DEGREES

This image, the reason I ventured out into the night, originally eluded me, causing me to turn a half circle to discover a totally different scene and feel waiting just over my shoulder. 20 sec., f/8, ISO 100, 20mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I WISH I HAD A LEICA for every time I came away from a shooting project with something completely opposite from the prize I was originally seeking. The odd candid moment, the last-minute change of light, the bizarre intervening event….there are so many random factors even in the shots that are the most meticulously planned that photography is kept perpetually fresh, since it is absolutely impossible to ensure its end results, especially for infants playing at my level. That point was dramatically brought home to me again a few weeks ago, and all I had to do was turn my head 180 degrees.

All during a week’s stay at a conference center near Yosemite National Park, I had been struck by how the first view a visitor got of the main lodge and its surrounding pond, from an approach road slightly above the building, was by far a better framing of the place than could be had anywhere else on the grounds. A few days of strolling by the lodge from several approaches had not provided any better staging of the quiet scene, but, with the harshness of the daylight at that altitude, I was convinced that a long exposure done just after nightfall would convey a more peaceful, intimate mood than I could ever hope to capture by day. And so, on the evening before I was to leave the lodge for home, I decided to take my tripod to the approach road and set up for a try.

The road is rather twisty and narrow, and so its last turn before heading for the lodge’s parking areas is lit with a street lamp, and a bloody bright one at that. It’s a sodium vapor light, which registers very orange to the eye. I’m used to these monsters, since, back home in Phoenix, they are the predominant city light sources, creating less long-distance “light pollution” for astronomers in Flagstaff trying to see the finer features in the night sky. At any rate, the road was so bright that I had to set up closer to the lodge than originally planned in order to avoid a lot of ambient light over my shoulder killing the subdued dark I wanted for my shot. Intervening event and last-minute change of light. Changing my stance, I was also having problems with movement on the pond surface. It was a tad too swift to allow for a mirroring of the lodge, and a long exposure was going to soften it up even more. I was going to get pretty colors, but they would be diffuse and gauzy rather than reflective. At the same time I was trying to avoid framing another lamp, this one to the right of the lodge. Illuminating a walking path, it would, over the length of the exposure, pretty much burn its way into the scene and distract from the impact. Typical problems, but I was already losing my love for the project, and after about a half-dozen flubbed attempts, I was trying to avoid mouthing several choice Anglo-Saxon epithets.

It was the need to take a break that had me looking around to see if anything else could be done under the conditions, and that’s when I turned my head to really see the light from the approach road that had been over my shoulder. Candid moment. Now I saw that orange light illuminating the road, the rustic fence, and the surrounding trees and shrubs in an eerie, Halloween-ish cast. The same scene in daylight or natural color would have registered just as “some nice trees”, but now it was Sleepy Hollow, the scary walk home after the goblins come out, the place where evil things breed. Better yet, if I stepped just about six inches to the right of where I was standing, the hated lamp-post would be totally obscured by the largest tree in the shot, casting its shadow another 20 or so feet longer and serving up a little added drama as a bonus. Suddenly, the lamp had been transformed from a fiend to a friend. I swiveled the tripod’s head around, set the shot, and got where I needed to be in two clicks.

After first trying (and failing) to nail the image of the lodge, I pivoted around and found this scene, which had been waiting to be discovered right behind me. Once I shot this, I turned around and made one more attempt on the lodge, using, as it turned out, the exact same setting as this picture; 20 sec., f/8, ISO 100, 20mm.

Better yet, the break in the action allowed me to re-boot my head vis-a-vis the lodge image. I turned back around, and, oddly, with the exact same exposure settings, hit a balance I could live with. Neither shot was perfect, but the creation of one had actually enabled the capture of the other. On the walk back to my cabin, I was already dissecting the weaknesses in both, but they each, in turn, had taught me, again, the hardest lessons, for me, in photography. Slow down. Look. Think. Plan, but don’t be afraid of reactive instinct. Sometimes, a sacred plan can keep you from “getting the picture”, figuratively and literally.

All I have to do is remember to turn my head around.

SLOGGING INTO HISTORY

Landing craft and tanks at Omaha beach during the D-Day landings, many of which had departed from Penarth (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE SHEER WEIGHT OF THE NUMBERS attendant to the D-Day invasion, begun sixty-eight years ago today, beggars the imagination. And yet, faced with the even tougher task of weighing the unimaginable horror and slaughter played out on the beaches of Normandy, the ability to somehow quantify the cost in raw data is oddly comforting. It’s certainly easier than evaluating the loss to the world, in muscle and blood, of the largest military operation in recorded history. Some selected figures:

The players: one million Allies, seven hundred thousand German troops.

The hardware: 8.000 artillery pieces; 2,546 Allied bombers and 1,731 fighters, 820 German bombers and fighters; 3,500 towed gliders (100 glider pilots killed).

Lost materiel: 24 warships and 35 merchant ships sunk; 127 allied planes shot down.

The human cost of the initial invasion in gross numbers: 6,603 Americans, 2,700 British, 946 Canadians, and between 4,000 and 9.000 Germans;

And then there was the “before” killing and the “after” killing, with 12,000 airmen and 200 war planes lost in April and May 1944 in preparation for 6/4/44, and a general toll by the end of the Battle of Normandy of 425,000 Allies and Germans killed or wounded.

Today, in Normandy, spread across 77 separate cemeteries lie the remains of 77,866 Germans; 9,386 Americans; 17,769 British; 5,002 Canadians and 650 Poles.

Related articles

- ‘Band of Brothers’ honored on D-Day anniversary (newsobserver.com)

- June 6, 1944: Artificial Harbor Paves the Way for Normandy Invasion (wired.com)