STOP AT “YES”

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE SEEMS TO BE A PROPENSITY, WITHIN THE DNA OF EVERY PHOTOGRAPHER, to “show it all”, to flood the frame with as much visual information as humanly possible in an attempt to faithfully render a story. Some of this may track back to the first days of the art, when the world was a vast, unexplored panorama, a wilderness to be mapped and recorded. Early shutterbugs risked their fortunes and their lives to document immense vistas, mountain ranges, raging cataracts, daunting cliffs. There was a continent to conquer, an immense openness to capture. The objectives were big, and the resultant pictures were epic in scale.

Seemingly, intimacy, the ability to select things, to zero in on small stories, came later. And for some of us, it never comes. Accordingly, the world is flooded with pictures that talk too loudly and too much, including, strangely, subjects shot at fairly close range. The urge is strong to gather, rather than edit, to include rather than to pare away. But there are times when you’re just trying to get the picture to “yes”, the point at which nothing else is required to get the image right, which is also the point at which, if something extra is added, the impact of the image is actually diminished. I, especially, have had to labor long and hard to just get to “yes”….and stop.

In the above image, there are only two elements that matter: the border of brightly lit paper lanterns at the edge of a Chinese New Year festival and the small pond that reflects back that light. If I were to exhaust myself trying to also extract more detail from the surrounding grounds or the fence, I would accomplish nothing further in the making of the picture. As a matter of fact, adding even one more piece of information can only lessen the force of the composition. I mention this because I can definitely recall occasions when I would whack away at the problem, perhaps with a longer exposure, to show everything in more or less equal illumination. And I would have been wrong.

Even with this picture, I had to make myself accept that a picture I like this much required so little sweat. Less can actually be more, but we have to learn to get out of our own way….to stop at “yes”.

DRIVING THE IMAGE

YOU CAN FILL A LIBRARY SHELF WITH OPPOSING ARGUMENTS ON LIGHT’S ROLE IN PHOTOGRAPHY, not necessarily a debate on how to capture or measure it, but more a philosophical tussle on whether light is a mere component in a photograph or enough reason, all by itself, for the image to be made, regardless of the subject matter.

The answer, for me, is different every time, although more often than not I make pictures purely because the light is here right now, and it will not wait. I actually seem to hear a clock beginning to tick from the moment I discover certain conditions, and, from that moment forward, I feel as if I am in a kind of desperate countdown to do something with this finite gift before it drifts, shifts, or otherwise mutates out of my reach. Light is running the conversation, driving the image.

“In the right light, at the right time, everything is extraordinary”, the photographer Aaron Rose famously said, and I live for the chance to ennoble or, if you will, sanctify something by how it models or is embraced by light. Certainly I usually go out looking for things to shoot, but time and time again something shifts in my priorities, forcing me to look for ways to shoot.

The practical world will look at a photograph and ask, understandably,  “what is that supposed to be?”, or, more pointedly, “why did you take a picture of that?” This makes for quizzical expressions, awkward conversations and sharp disagreements within gallery walls, since our pragmatic natures demand that there be a point, an objective in all art that is as easily identifiable as going to the hardware for a particular screw. Only life, and the parts of life that inspire, can’t ever function that way.

“what is that supposed to be?”, or, more pointedly, “why did you take a picture of that?” This makes for quizzical expressions, awkward conversations and sharp disagreements within gallery walls, since our pragmatic natures demand that there be a point, an objective in all art that is as easily identifiable as going to the hardware for a particular screw. Only life, and the parts of life that inspire, can’t ever function that way.

We often decide to make an important picture of something rather than make a picture of something important. That’s not just artsy double-talk. It’s truly the decision that is placed before us.

Alfred Steiglitz remarked that “wherever there is light, photography is possible”. That’s an unlimited, boundless license to hunt for image-makers. Just give me light, the photographer asks, and I will make something of it.

ONE OUT OF FOUR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF YOU ARE DEPENDENT ON NATURAL LIGHT FOR YOUR ONLY SOURCE OF ILLUMINATION IN AN IMAGE, you have to take what nature and luck afford you. Making a photograph with what’s available requires flexibility, patience, and, let’s face it, a sizable amount of luck. It means waiting for your moment, hell, maybe your instant of opportunity, and it also means being able to decide quickly that now is the time (perhaps the only time) to press the button.

I recently had such a situation, measured in the space of several seconds in which the light was ready and adequate for a shot. And, as usual, the subject seemed as if it would serve up anything but acceptable conditions. The main bar of the classic western “joint” named Greasewood Flats, just outside of northern Scottsdale, Arizona, is anything but ideal in its supply of available light. Most of the room is a tomb, where customers become blobby silhouettes and fixtures and features are largely cloaked in shadow. I had squeezed off a few shots of customers queued up for bar orders, and they all registered as shifting shadows. The shots were unworkable, and I turned my attention to the fake-cowboy-ersatz-dude-ranch flavor of the grounds outside the bar, figuring that the hunt inside would be fruitless.

Minutes later, I was sent back inside the building to fetch a napkin, and found the bar empty of customers. I’m talking no human presence whatever. In an instant, I realized that the outside window light, which was inadequate to fill a four-sided, three-dimensional space, was perfectly adequate as it spread along just one wall. With crowds out of the way, the rustic detail that made the place charming was suddenly a big still-life, and the whole of that single wall was suddenly a picture. My earlier shots were too constrasty at f/5.6, so I tried f/3.5 and picked up just enough detail to fill the frame with Old West flavor. Click.

All natural light is a gift, but it does what it wants to do, and, to harness it for a successful shot, you need to talk nice, wait your turn, and remember to give thanks. And, in a dark room, be happy with one wall out of four that wants to work with you.

MORE BOUNCE TO THE OUNCE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR THE MOST PART, THE USE OF ON-CAMERA FLASH SHOULD BE CONSIDERED A CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY. Scott Kelby, the world’s best-selling author of digital photography tutorials, famously remarked that “if you have a grudge against someone, shoot them with your pop-up flash, and it will even the score.” But, to be fair, let’s look at the pros and cons of using on-board illumination:

PROS : Cheap, handy

CONS: Harsh, Weak, Unflattering, Progenitor of Red-eye. Also, Satan kills a puppy every time you use it. Just sayin’.

There are, however, those very occasional situations where supplying a little bit of extra light might give you just the fill you need on a shot that is getting 90% of its light naturally. Even so, you have to employ trickery to harness this cruel blast of ouch-white, and simple bounces are the best way to get at least some of what you want.

In the above situation, I was shooting in a hall fairly flooded with bright mid-morning light, which was extremely hot on the objects it hit squarely but contrasty as an abandoned cave on anything out of its direct path. The fish sculpture in my proposed shot was getting its nose torched pretty good, but in black and white, the remainder of its body fell off sharply, almost to invisibility. I wanted the fish’s entire body in the shot, the better to give a sense of depth to the finished picture, but I obviously couldn’t flash directly into the shelf that overhung it without drenching the rest of the scene in superfluous blow-out. I needed a tiny, attenuated, and cheap fix.

Bending a simple white stationery envelope into a “L”, I popped up my camera’s flash and covered the unit with the corner of the envelope where the two planes intersected. The flash was scooped up by the envelope, then channeled over my shoulder, blowing onto the wall at my back, then bouncing back toward the fish in softened condition near the underside of the shelf, allowing just enough light to allow the figure’s bright nose to taper back gradually into shadow, revealing additional texture, but not over-illuminating the area. It took about five tries to get the thing to look as if the light could have broken that way naturally. Fast, cheap, effective.

The same principle can be done, with some twisting about, to give you a side or ceiling bounce, although, if high reflectivity is not crucial, I frankly recommend using your hand instead of the envelope, since you can twist it around with greater control and achieve a variety of effects.

Of course, the goal with rerouting light is to look as if you did nothing at all, so if you do save a picture with any of these moves, keep it to yourself. Oh, yes, you say modestly, that’s just the look I was going for.

Even as you’re thinking, whew, fooled ’em again.

THE RELENTLESS MELT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE PEOPLE YOU PHOTOGRAPH BECAUSE THEY ARE IMPORTANT. Others are chosen because they are elements in a composition. Or because they are interesting. Or horrific. Or dear in some way. Sometimes, however, you just have to photograph people because you like them, and what they represent about the human condition.

That was my simple, solid reaction upon seeing these two gentlemen engaged in conversation at a party. I like them. Their humanity reinforces and redeems mine.

This image is merely one of dozens I cranked out as I wandered through the guests at a recent reception for two of my very dearest friends. Given the distances many of us in the room traveled to be there, it’s unlikely I will ever see most of these people again, nor will I have the honor of knowing them in any other context except the convivial evening that herded us together for a time. Because I was largely eavesdropping on conversations between small groups of people who have known each other for a considerable time, I enjoyed the privilege often denied a photographer, the luxury of being invisible. No one was asked to pose or smile. No attempt was made to “mark the occasion” or make a record of any kind. And it proved to me, once more, that the best thing to relax a portrait subject is……another portrait subject.

I assume from the body language of these two men that they are friends, that is, that they weren’t just introduced on the spot by the hostess. There is history here. Shared somethings. I don’t need to know what specific links they have, or had. I just need to see the echoes of them on their faces. I had to frame and shoot them quickly, mostly to evade discovery, so in squeezing off several fast exposures I sacrificed a little softness, partly due to me, partly due to the animated nature of their conversation. It doesn’t bother me, nor does the little bit of noise suffered by shooting in a dim room at ISO 1000. I might have made a more technically perfect image if I’d had total control. Instead, I had a story in front of me and I wanted to possess it, so….

Susan Sontag, the social essayist whose final life partner was the photographer Annie Liebovitz, spoke wonderfully about the special theft, or what she called the “soft murder” of the photographic portrait when she noted that “to take a photograph is to participate in another person’s mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.”

Melt though it might, time also leaves a mark.

Caught in a box.

Treasured in the heart.

Related articles

- Susan Sontag Musings Where You Least Expect Them (hintmag.com)

HERE COMES THE NIGHT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR SOME PHOTOGRAPHERS, THE END OF A CALENDAR YEAR MEANS BUSTING OUT THE “BEST OF” LISTS, and, certainly,for people with a certain level of skill, that’s a normal instinct. I am always far too horrified by how many losing horses I put in a given year’s race to try to find the few who didn’t go lame, wander off the track, or finish last, so I confine my year’s-end computations to lists of what I tried, and whether I got close to learning anything. For 2013, one bulletin emerges:

I like the dark. A lot.

That is, a simple head count of shots taken this year reveal that I was outside, after supper, at nearly every opportunity. And yes, with mixed results. Always and forever will them results be mixed, amen. If my results were in a Waring blender, going at full “puree” speed, they could not be more mixed, okay?

But for some reason, the quest took me back into a renewed appreciation of shadows, shades, a lack of light. I probably embraced the missing information and detail that the dark represents more joyfully than I have in many years. And that’s something of a journey, since, if I had any kind of post-processing crack habit recently, it was the mania to rescue more and more of that detail, whether in High Dynamic Range photos, Exposure Fusion photos or Tone Compression photos. For a while, I was acting like your Grandpa the first week he owned his new Magnavox (“…hmm, needs a little more green….no, now the horses look purple….let’s add some red…”).

Maybe 2013 was the year I pulled back a bit and just let darkness be, let it express the unknown and the unknowable. Photography is always at least partly about what you don’t show, not depicting the world as a giant Where’s Waldo overdose of texture and detail. In ’13, I spent a lot more time shooting night shots at the technical limit of my camera, but did not fiddle about much further afterwards. I was interested in “getting as much picture into the click” as possible, but what couldn’t be achieved with faster lenses or mildly enhanced ISO just got left out of the pictures. I feel like it was a year of correction, with me playing the part of a new teen driver has to learn to correct for over-steer.

The whole thing is about remembering that technique is not style. What you have to say is style. The mechanical means you use to get it said is technique. Learning to execute a technique is like mastering the workings of a camera. It does not guarantee that your results will be revelatory or eloquent. That means that falling in love with the consistent polishing of processing is a danger, since you can begin to love it for its own sake. Technique says “Look what I can do!”. Style says, “but, is this what I should be doing?”

Anyway, whatever I presently think is essential for my growth will, eventually, become just one more thing that I do, and will be supplanted by something else. That said, a good year in photography should not end with the collection of a pile of hits, but an unafraid assessment of the misses.

That’s where the next batch of good pictures will come from, anyway.

ANOTHER YEAR OUT THE WINDOW

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF YOU WANT TO PUT A SMILE ON MY FACE WHEN I VISIT YOUR CITY, there is no sweeter sentence you can say to me than:

“I’ll drive”.

There is, for photographers, one way to maximize your time touring through other people’s towns, and that’s the time-honored tradition of “riding shotgun”. Drive me anywhere, but give me a window seat. I wasn’t trying to go for some kind of personal best in the area of urban side shots in 2013, but by good fortune I did snag a few surprises as I was ferried through various towns, along with a “reject” pile about a mile high. Like any other kind of shooting, the yield in window shooting is very low in terms of “killers per click”, but when you hit the target, you crack through a kind of “I’m new in town” barrier and take home a bit of the street for your own.

This guy just killed me (excuse the expression). He seemed like he was literally waiting for business to drop in (or drop dead), and meanwhile was taking in the view. Probably he didn’t even work for the casket company, in which case, what a bummer of neighbor to pick. Maybe he’s rent controlled.

This one took a little tweaking. The building was actually blue, as you see here, lit with subdued mood for the holidays. However, in lightening this very dark shot, the sky registered as a muddy brown, so I made a dupe, desaturated everything except the conservatory, then added tint back in to make the surrounding park area match the building. All rescued from an “all or nothing” shot.

I’m also ashamed to admit that I bagged a few through-the-window shots while actually driving the car, all done at red lights and so not recommended. Don’t do as I do, do as I……oh, you know.

Here’s to long shots, at horse tracks or in viewfinders, and the few that finish in the money.

EAVESDROPPING ON REALITY

Stepping onto Blenkner Street and into history. Columbus, Ohio’s wonderful German Village district, December 2013. 1/60 sec., f/1.8, ISO 800, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE FAMILIAR ADMONITION FROM THE HIPPOCRATIC OATH, the exhortation for doctors to, “First, Do No Harm” has applications to many kinds of enterprises beyond the scope of medicine, photography among them. We are so used to editing, arranging, scouting, rehearsing and re-imagining reality that sometimes, we need merely to eavesdrop on it.

Some pictures are so complete in themselves that, indeed, even minimal interference from a photographer is a bridge too far. Sometimes such images come as welcome relief after a long, unproductive spell of trying to force subjects into our cameras, only to have them wriggle away like so much conceptual smoke. I recently underwent several successive days of such frustration in, of all things, my own home town, fighting quirky weather, blocked access, and a blank wall of my own mental making. I finally found something I can use in (say it all together) the last place I was looking.

In fact, it was a place I hadn’t wanted to be at all.

Columbus, Ohio at night in winter is lots of things, but it’s seldom conducive to any urge more adventurous than reheating the Irish coffee and throwing another log on the fire. At my age, there’s something about winter and going out after sunset that screams “bad idea” to me, and I was reluctant to accept a dinner invite that actually involved my schlepping across the tundra from the outskirts to the heart of downtown. Finally, it was the lure of lox and bagel at Katzinger’s deli, not my artistic wanderlust, that wrenched me loose from hearth and home, and into range of some lovely picture-making territory.

The German Village neighborhood, along the city’s southern edge, has, for over a century, remained one of the most completely intact caches of ethnic architecture in central Ohio, its twisty brick streets evoking a mini-Deutschland from a simpler time. Its antique street lamps, shuttered windows and bricked-in gartens have been an arts and party destination for generations of visitors, casting its spell on me clear back in high school. Arriving early for my trek to Katzie’s, I took advantage of the extra ten minutes to wander down a few familiar old streets, hoping they could provide something….unfamiliar.

The recently melted snowfall of several days prior still lent a warm glaze to the cobbled alleyways, and I soon found myself with city scenes that evoked a wonderful mood with absolutely minimal effort. The light was minimal as well, often coming from just one orange sodium-vapor street lamp, and it made sense to make them the central focus of any shots I was to take, allowing the eye to be led naturally from the illuminated streets at the front of the frame clear on back to the light’s source.

Using my default lens, a 35mm prime at maximum f/1.8 aperture, and an acceptable amount of noise at ISO 800, I clicked away like mad, shooting up and down Blenkner Street, first toward Third Street, then back around toward High. I didn’t try to rescue the details in the shadows, but let the city more or less do its own lighting with the old streets. I capped my lens, stole away like the lucky thief I had become, and headed for dinner.

The lox was great, too. Historic, in fact.

KEEPING SPIRITS BRIGHT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT IS A SEASON OF LIGHT AND COLOR, perhaps one of the key times of the year for all things illuminated, burning, blazing and glowing. It is a time when opportunities for vivid and brilliant images explode from every corner.

And one way to unleash all that light is to manage darkness.

One example: your family Christmas tree involves more delicate detail, tradition and miniature charm than any other part of your home’s holiday decor, but it often loses impact in many snapshots, either blown out in on-camera flash or underlit with a few colored twinkles surrounded by a blob of piny silhouette.

How about a third approach: go ahead and turn off all the lights in the room except those on the tree, but set up a tripod and take a short time exposure.

It’s amazing how easy this simple trick will enhance the overall atmosphere. With the slightly slow exposure, the powerful tree LEDs have more than enough oomph to add a soft glow to the entire room, while acting as a multitude of tiny fill lights for the shaded crannies within the texture of the tree. Ornaments will be softly and partially lit, highlighting their design details and giving them a slightly dimensional pop.

In fact, the LED’s emit such strong light that you only want to make the exposure slow enough to register them. The above image was taken at 1/16 of a second, no longer, so the lights don’t have time to “burn in” and smear. And yes, some of you highly developed humanoids can hand-hold a shot steadily at that exposure, so see what works for you. You could also, of course, shoot wide open to f/1.8 if you have a prime lens, making things even easier, but you might run into focus problems at close range. You could also just jack up your ISO and shoot at a more manageable shutter speed, but in a darkened room you’re trading off for a lot of noise in the areas beyond the tree. Dealer’s choice.

Lights are a big part of the holidays, and mastery of light is the magic that delivers the mystery. Have fun.

DARK NIGHT, BRIGHT NIGHT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

OFTEN, THE SHOT YOU GET HAPPENS ON THE WAY TO THE SHOT YOU THOUGHT YOU WANTED. We all like to think we are operating under some kind of “master plan”, proceeding along a Spock-o-logical path of reason, toward a guaranteed ( and stunning) result, but, hey, this is photography, so, yeah, forget all that.

Night shots are nearly always a series of surprises/rude shocks for me, since sculpting or harvesting light after dark is a completely different skill from what’s used in the daytime. Even small tweaks in my approach to a given subject result in wild variances in the finished product, and so I often sacrifice “the shot” that I had my heart set on for the one which blossomed out of the moment.

This is all French for “lucky accident”. I’d love to attribute it to my own adventurous intellect and godlike talent, but, again, this is photography, so, yeah, forget all about that, too.

So, as to the image up top: in recent years, I have pulled away from the lifelong habit of making time exposures on a tripod, given the progressively better light-gathering range of newer digital sensors, not to mention the convenience of not having to haul around extra hardware. Spotting this building just after dusk outside my hotel the other night, however, I decided I had the time and vantage point to take a long enough exposure to illuminate the building fully and capture some light trails from the passing traffic.

Minutes before setting up my ‘pod, I had taken an earlier snap with nothing but available light, a relatively slow shutter speed and an ISO of 500 , but hadn’t seriously looked at it: traditional thinking told me I could do better with the time exposure. However, when comparing the two shots later, the longer, brighter exposure drained the building of its edgier, natural shadow-casting features, versus the edgier, somber, burnt-orange look of it in the snapshot. The handheld image also rendered the post-dusk sky as a rich blue, while the longer shot lost the entire sky in black. I wanted the building to project a slight air of mystery, which the longer shot completely bleached away. I knew that the snapshot was a bit noisy, but the better overall “feel” of the shot made the trade-off easier to live with. I could also survive without the light trails.

Time exposures render an idealized effect when rendering night-time objects, not an accurate recording of “what I saw”. Continual experimentation can sometimes modulate that effect, but in this case, the snatch-and-grab image won the day. Next time, everything will be different, from subject to result. After all, this is photography.

TAKE WHAT YOU NEED AND LEAVE THE REST

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LOOKING OVER MY LIFETIME “FAIL” PHOTOGRAPHS, FROM EARLIEST TO LATEST, it’s pretty easy to make a short list of the three main problems with nearly all of them, to wit:

Too Busy.

Too Much Stuff Going On.

I Don’t Know Where I’m Supposed To Be Looking.

Okay, you got me. It’s the same problem re-worded three ways. And that’s the point, not only with my snafus but with nearly other picture that fails to connect with anybody, anywhere. As salesmen do, photographers are always “asking for the order”, or, in this case, the attention of the viewer. Often we can’t be there when our most earnest work is seen by others. If the images don’t effectively say, this is the point of the picture, then we haven’t closed the deal.

It’s not simple, but, yeah, it is that simple.

If we don’t properly direct people to the main focus of our story, then we leave our audiences wandering in the woods, looking for a way out. Is it this path? Or this one?

In our present era, where it’s possible to properly expose nearly everything in the frame, we sometimes lose a connection to the darkness, as a way to cloak the unimportant, to minimize distraction, to force the view into a succinct part of the image. Nothing says don’t look here like a big patch of black, and if we spend too much time trying to show everything in full illumination, we could be throwing away our simplest and best prop.

Let sleeping wives lie. Work the darkness like any other tool. 1/40 sec., f/1.8, ISO 1250 (the edge of pain), 35mm.

In the above picture of my beautiful Marian, I had one simple mission, really. Show that soft sleeping face. A little texture from the nearby pillows works all right, but I’m just going to waste time and spontaneity rigging up a tripod to expose long enough to show extra detail in the chair she’s on, her sweatshirt, or any other surrounding stuff, and for what? Main point to consider: she’s sleeping, and (trust me) sleeping lightly, so one extra click might be just enough to end her catnap (hint: reject this option). Other point: taking extra trial-and-error shots just to show other elements in the room will give nothing to the picture. Make it a snapshot, jack up the ISO enough to get her face, and live with the extra digital noise. Click and done.

For better or worse.

Composition-wise, that’s often the choice. If you can’t make it better, for #%$&!’s sake don’t make it worse.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

HOLLYWOOD NIGHTS

Moonlight night around the poolside, only not really: a “day-for-night” shot taken at 5:17pm. 1/400 sec., f/18, ISO 100, 35mm, using a tungsten white balance.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

TIME LIMITS US IN EVERY PHOTOGRAPHIC SITUATION: LIGHT HEMS US IN EVEN FURTHER. Of course, the history of photography is rife with people who refuse to just accept what time and nature feel like giving them. In fact, that refusal to settle is source of all the artistry. Too bright? Too bland? Wrong time of day? Hey, there’s an app for that. Or, more precisely, a work-around. Recently, I re-acquainted myself with one of the easiest, oldest, and more satisfying of these “cheats”, a solid, simple way to enhance the mood of any exterior image.

And to bend time… a little.

Same scene as above taken just seconds later, but with normal white balancing and settings of 1/250 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

It’s based on one of Hollywood’s long-standing budget-savers, a technique called day-for-night. For nearly a century, cinematographers have simulated nightfall while shooting in the daytime, simply by manipulating exposure or processing. Many of the movie sequences you see represented as “night” are, in fact, better lit than any “normal” night, unless you’re under a bright, full moon. Day-for-night allows objects to be more discernible than in “real” night because their illumination is actually coming from sunlight, albeit sunlight that’s been processed differently. Shadows are starker and it’s easier to highlight what you want to call attention to. It’s also a romantically warm blue instead of, well, black. It’s not a replication of reality. Like most cinematic effects, it’s a little bit better than real.

If you’re forced to approach your subject hours before sunset, or if you simply want to go for a different “feel” on a shot, this is a great shortcut. Even better, in the digital era, it’s embarrassingly easy to achieve: simple dial up a white balance that you’d normally use indoors to balance incandescent light. Use the popular “light bulb” icon or a tungsten setting. Indoors this actually helps compensate for cold, bluish tones, but, outside, it amps up the blue to a beautiful, warm degree, especially for the sky. Colors like reds and yellows remain, but under an azure hue.

The only other thing to play with is exposure. Shutter-speed wise, head for the high country

at anywhere from f/18 to 22, and shorten your exposure time to at least 1/250th of a second or shorter. Here again, digital is your friend, because you can do a lot of trial and error until you get the right mix of shadow and illumination. Hey, you’re Mickey Mouse with the wizard hat on here. Get the look you want. And don’t worry about it being “real”. You checked that coat at the door already, remember?

Added treats: you stay anchored at 100 ISO, so no noise. And, once you get your shot, the magic is almost completely in-camera. Little or no post-tweaking to do. What’s not to like?

I’m not saying that you’ll get a Pulitzer-winning, faux-night shot of the Eiffel Tower, but, if your tour bus is only giving you a quick hop-off to snap said tower at 2 in the afternoon, it might give you a fantasy look that makes up in mood what it lacks in truth.

It ain’t the entire quiver, just one more arrow.

Follow Michael Perkins at Twitter @MPnormaleye.

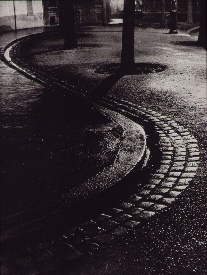

SCULPTING WITH SHADOWS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

Brassai‘s world came to light at night.

ONE OF THE MIRACLES OF CONTEMPORARY PHOTOGRAPHY is how wonderfully oblivious we can afford to be to many of the mechanics of taking a picture. Whereas, in an earlier era, technical steps 1, 2, 3, 4 ,5, and 6 had to be completed before we could even hit the shutter button, we now routinely hop from “1” to “snap” with no thought of the process in between.

In short, we don’t have to sweat the small stuff, a truth that I was reminded of this week when imitating one of photographer’s earliest masters of night photography, Gyula Halasz, or “Brassai”, a nickname which refers to his hometown in Romania. Starting around 1924, Brassai visually made love to the streets of Paris after dark with the primitive cameras of the early 20th century, sculpting shape from shadow with a patiently laborious process of time exposures and creating ghostly, wonderful chronicles of a vanished world. He evolved over decades into one of the most strikingly romantic street artists of all time, and was one of the first photographers to have a show of his work mounted at New York’s MOMA.

Recently, the amazing photo website UTATA (www.utata.org), a workshop exchange for what it calls “tribal photography”, gave its visitors a chance to take their shot at an homage to half a dozen legendary visual stylists. The assignment asked Utata members to take images in the style of their favorite on the list, Brassai being mine.

In an age of limited lenses and horrifically slow films, Brassai’s exposure times were long and hard to calculate. One of his best tricks was lighting up a cigarette as he opened his lens, then timing the exposure by how long it took for the cig to burn down. He even used butts of different lengths and widths to vary his effect. Denizens of the city’s nightlife, walking through his long shots, often registered as ghosts or blurs, adding to the eerie result in photos of fogbound, rain-soaked cobblestone streets. I set out on my “homage” with a tripod in tow, ready to likewise go for a long exposure. Had my subject been less well-lit, I would have needed to do just that, but, as it turned out, a prime 35mm lens open to f/1.8 and set to an ISO of 500 allowed me to shoot handheld in 1/60 of a second, cranking off ten frames in a fraction of the time Brassai would have needed to make one. I felt grateful and guilty at the same time, until I realized that a purely technical advantage was all I had on the old wizard.

“Faux Brassai”, 2013. Far easier technically, far harder artistically. 1/60 sec., f/1.8, ISO 500, 35mm.

Brassai has shot so many of the iconic images that we have all inherited over the gulf of time that one small list from one small writer cannot contain half of them. I ask you instead to click the video link at the end of this post, and learn of, and from, this man.

Many technical land mines have been removed from our paths over photography’s lifetime, but the principal obstacle remains…the distance between head, hand, and heart. We still need to feel more than record, to interpret, more than just capture.

All other refinements are just tools toward that end.

THANKS TO OUR NEW FOLLOWERS! LOOK FOR THEM AT:

http://www.en.gravatar.com/icetlanture

http://www.en.gravatar.com/aperendu

Related articles

- Wonderful Photos of New York in 1957 by Brassaï (vintag.es)

THE WOMAN IN THE TIME MACHINE

by MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE TIMES WHEN A CAMERA’S CHIEF FUNCTION IS TO BEAR WITNESS, TO ASSERT THAT SOMETHING FANTASTIC REALLY DID EXIST IN THE WORLD. Of course, most photography is a recording function, but, awash in a sea of infinite options, it is what we choose to see and celebrate that makes an image either mundane or majestic.

And then sometimes, you just have the great good luck to wander past something wonderful. With a camera in your hand.

The New York Public Library’s main mid-town Manhattan branch is beyond magnificent, as even a casual visit will attest. However, its beauty always seems to me like just “the front of the store”, a controlled-access barrier between its visually stunning common areas and “the good stuff” lurking in untold chambers, locked vaults and invisible enclaves in the other 2/3 of the building. I expect these two worlds to be forever separate and distinct, much as I don’t expect to ever see the control room for electrical power at Disneyland. But the unseen fascinates, and recently, I was given a marvelous glimpse into the other side at the NYPL.

A recent exhibit of Mary Surratt art prints, wall-mounted along the library’s second-floor hall, was somehow failing to mesmerize me when, through a glass office window, I peeked into a space that bore no resemblance whatever to a contemporary office. The whole interior of the room seemed to hang suspended in time. It consisted of a solitary woman, her back turned to the outside world, seated at a dark, simple desk, intently poring over a volume, surrounded by dark, loamy, ceiling-to-floor glass-paneled book shelves along the side and back walls of the room. The whole scene was lit by harsh white light from a single window, illuminating only selective details of another desk nearer the window, upon which sat a bust of the head of Michelangelo’s David, an ancient framed portrait, a brass lamp . I felt like I had been thrown backwards into a dutch-lit painting from the 1800’s, a scene rich in shadows, bathed in gold and brown, a souvenir of a bygone world.

I felt a little guilty stealing a few frames, since I am usually quite respectful of people’s privacy. In fact, had the woman been aware of me, I would not have shot anything, as my mere perceived presence, however admiring, would have felt like an invasion, a disturbance. However, since she was oblivious to not only me, but, it seemed, to all of Planet Earth 2013, I almost felt like I was photographing an image that had already been frozen for me by an another photographer or painter. I increased my Nikon’s sensitivity just enough to get an image, letting the light in the room fall where it may, allowing it to either bless or neglect whatever it chose to. In short, the image didn’t need to be a faithful rendering of objects, but a dutiful recording of feeling.

How came this room, this computer-less, electricity-less relic of another age preserved in amber, so tantalizingly near to the bustle of the current day, so intact, if out of joint with time? What are those books along the walls, and how did they come to be there? Why was this woman chosen to sit at her sacred, private desk, given lone audience with these treasures? The best pictures pose more questions than they answer, and only sparingly tell us what they are “about”. This one, simply, is “about” seeing a woman in a time machine. Alice through the looking-glass.

A peek inside the rest of the store.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

Thanks to THE NORMAL EYE’s latest follower! View NAFWAL’s profile and blog at :

A BRIEF AUDIENCE WITH THE QUEEN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS ONLY ONE KIND OF PICTURE YOU WILL EVER TAKE OF A CAT, and that is the one she allows you to take. Try stealing an image from these spiritual creatures against their will, and you will reign over a bitter kingdom of blur, smear, and near misses.

It’s trickier to take photos of the ectoplasmic projections of departed relatives. But not by much.

I recently encountered this particular lady in a Brooklyn brownstone, a gorgeous building, but not one that is exactly flooded with light, even on a bright day. There are a million romantically wonderful places for darkness to hide inside such wonderful old residences, and any self-respecting feline will know how to take the concept of “stealth” down a whole other road. The cat in the above photo is, believe me, better at instant vaporization and re-manifestation than Batman at midnight in Gotham. She also has been the proud unofficial patrol animal for the place since Gawd knows when, so you can’t pull any cute little “chase-the-yarn-get-your-head-stuck-in-a-blanket” twaddle that litters far too much of YouTube.

You’re dealing with a pro here.

Her, not me.

Plus she’s from Brooklyn, so you should factor some extra ‘tude into the equation.

The only lens that gives me any luck inside this house is a f/1.8 35mm prime, since it’s ridiculously thirsty for light when wide open and lets you avoid the noticeable pixel noise that you’d get jacking up the ISO in a dark space. Thing is, at that aperture, the prime also has a razor-thin depth of field, so, as you follow the cat, you have to do a lot of trial framings of the autofocus on her face, since getting sharp detail on her entire body will be tricky to the point of nutso. And of course, if you move too far into shadow, the autofocus may not take a reading at all, and then there’s another separate complication to deal with.

The best (spelled “o-n-l-y”) solution on this particular day was to squat just inside the front foyer of the house, which receives more ambient light than any other single place in the house. For a second, I thought that her curiosity as to what I was doing would bring her into range and I could get what I needed. Yeah, well guess again. She did, in fact, approach, but got quickly bored with my activity and turned to walk away. It was only a desperate cluck of my tongue that tricked her into turning her head back around as she prepared to split. Take your stupid picture, she seemed to say, and then stop bothering me.

Hey, I ain’t proud.

My brief audience with the queen had been concluded.

I’ll just show myself out……

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

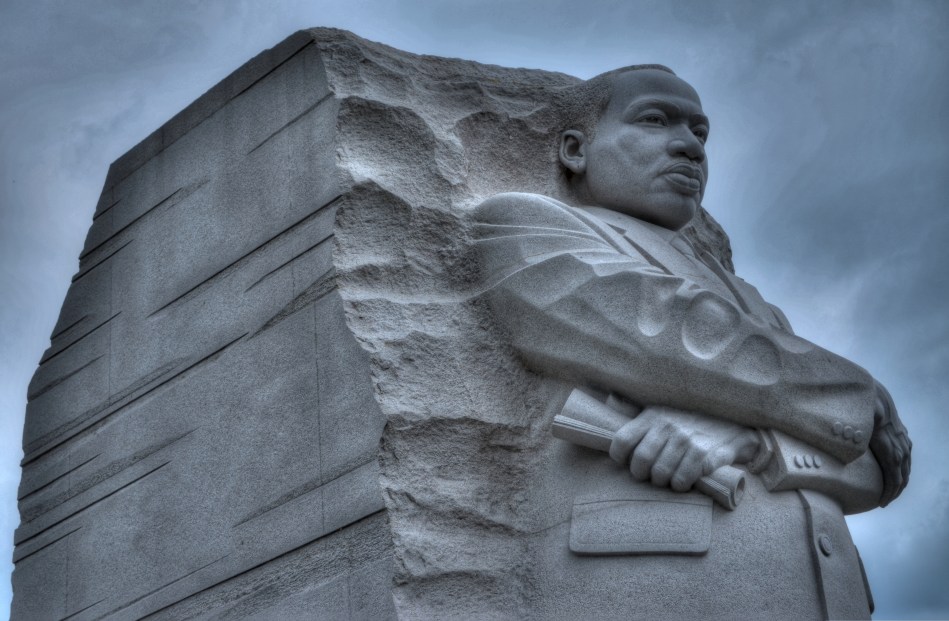

A TALE OF TWO KINGS

A determined Martin Luther King, Jr. stares forward into the future at the newly dedicated MLK Memorial on Washington’s National Mall. Fusion of three exposures, all with an aperture of f/5.6, all ISO 100, all 48mm. The shutter speeds, due to the high tones in the white statue, are 1/200, 1/320, and 1/500 sec.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

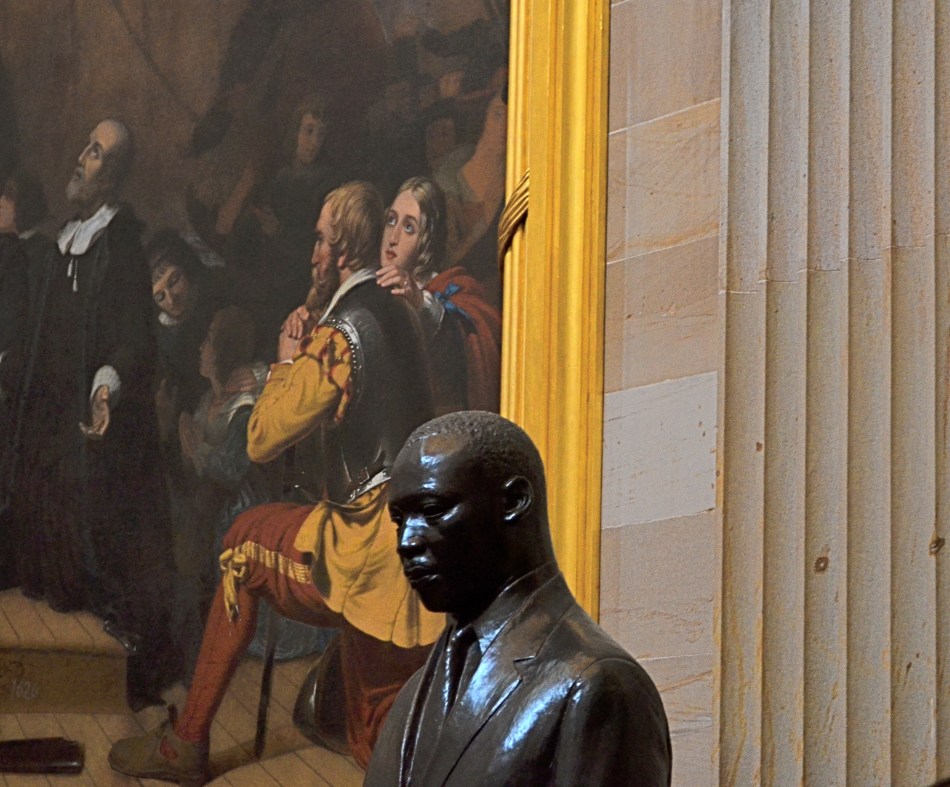

DEATH PERMANENTLY RENDERS REAL HUMAN BEINGS INTO ABSTRACTIONS. With every photo, formerly every painting, drawing, or statue of a renowned person, some select elements of an actual face are rearranged into an approximation, a rendering of that person. Not the entire man or woman, but an effect, a simulation. The old chestnut that a certain image doesn’t do somebody “justice”, or the mourner’s statement that the body in the casket doesn’t “look like” Uncle Fred are examples of this strange phenomenon.

Nothing amplifies that abstraction like having your image “officially” interpreted or commemorated after death, and, in the case of the very public Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Washington’s National Mall offers two decidedly contrasting ways of “seeing” the civil rights pioneer. One is more or less a tourist destination, while the other is muted, nearly invisible amongst the splendors of the U.S. Capitol. Both offer a distinct point of view, and both are, in a way, incomplete without the other.

The official MLK memorial, opened in 2011 as one of the newest additions to the Mall, stands at the edge of the Tidal Basin, directly across a brief expanse of water from the Jefferson Memorial. Its main feature shows a determined, visionary King, a titanic figure seeming to sprout from a huge slab of solid stone, as if, in the words of the monument, “detaching a stone of hope from a mountain of despair”. Arms folded, eyes fixed on a point some distance hence, he is calm, confident, and resolute. This gleaming white sculpture’s full details can best be captured with several bracketed exposures (fast shutter speeds) blended to highlight the grain and texture of the stone, but such a process abstract’s King even further into something out of history, majestic but idealized, removed.

Another view: a somber bronze bust of Dr. King in the U.S. Capitol rotunda, flanked by the painting The Embarkation Of The Pilgrims. 1/30 sec., f/5.6, ISO 640, 55mm.

The contrast could not be greater between this view and the bronze bust of King installed in 1988 in the rotunda of the Capitol building. This King is worried, subdued, straining under the weight of history, burdened by destiny. The bust gains some additional spiritual context when framed against its near neighbor, Robert Weir’s painting The Embarkation Of The Pilgrims, which shows the weary wayfarers of the Mayflower, bound for America, on bended knee, praying for freedom, for justice. Used as background to the bust, they resemble a kind of support group, a congregation eager to be led. Context mine? Certainly, but you shoot what you see. Inside the capitol, light from the dome’s lofty skylights falls off sharply as it reaches the floor, so underexposure is pretty much a given unless you jack up your ISO. Colors will run rich, and some post-lightening is needed. However, the dark palette of tones seems to fit this somber King, just as the triumphant glow of the MLK Memorial’s King seems suited to its particular setting.

Death and fame are twin transfigurations, and what comes through in any single image is more highly subjective than any photo taking of a living person.

But that’s where the magic comes in, and where mere recording can aspire to become something else.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

JOINTS

Try the special. Heck, it’s all special at the lunch counter at McAlpine’s Soda Fountain in Phoenix. 1/100 sec., f/1.8, ISO 100 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

BETTER MINDS THAN MINE HAVE LAMENTED THE HOMOGENIZING OF URBAN LIFE, that process by which uniqueness is gradually engineered out of human experience in buildings, businesses and products, to be replaced by the standardized, the research-proven, the chain-generated.

We all say we hate it. And we all put the lie to that statement by making the super-brands, all those golden arches and whole food superstores, more and more fabulously wealthy.

As a photographer, I feel a particular pang for the ongoing vanishing act that occurs in our cities. Who wants to aspire to take more and more pictures of less and less? Is a Starbucks in Kansas City really going to give me a profoundly different experience than a Starbucks in Jackson Mississippi? How, through creative location of the mug racks? And here, in the name of honesty, I have to catch myself in my own trap, since I also often default to something “safe” over something “unproven”. That is, I am as full of it as everyone else, and every day that I don’t choose to patronize someplace special is a day that such places come closer to the edge of the drain.

So.

It’s a delight to go someplace where fashion, and relevance, and context have all been rendered moot by time. Where, finally, just the fact that you have lasted this long means you can probably do so indefinitely. Such a place is McAlpine’s Soda Fountain Restaurant in central Phoenix. Birthed in 1926, the place was itself a part of America’s first huge surge of chain stores, originally housing a Rexall Pharmacy but centered around its fountain counter. The fare was, and remains, simple. No pondering over trans fats, no obsessing over sugar, no hair-raising tales of gluten reactions. Gourmet means you take your burger with both ketchup and mustard. “Soda” implies not mere fizzy water but something with a huge glob of ice cream in it. Thus your “drink” may also be your dessert, or you can just skip the meal pretense altogether and head right for the maraschino cherries.

McAlpine’s is a place where the woods of the booths are dark, and the materials of general choice are chrome, marble, neon, glass. Plastic comes later, unless you’re talking about soda straws. The place is both museum and active business, stacking odd period collectibles chock-a-block into every nook as if the joint itself weren’t atmosphere enough. But hey, when you’re a grand old lady, you can wear a red hat and white gloves and waist-length pearls, and if you don’t like it, take a hike, thankyouverymuch.

Three plays for a quarter, so you can eat “Tutti Fruiti” and listen to it, too. 1/40 sec., f/1.8, ISO 100, 35mm.

Graced with a 35mm prime lens opened all the way to f/1.8 and great soft midday light from the store’s front window, I could preserve the warm tones of the counter area pretty much as they are. For the booths, a little slower shutter speed was needed, almost too long for a handheld shot, but delivering a more velvety feel overall. Both shots are mere recordings, in that I was not trying to “sculpt” or”render” anything. McAlpine’s is enough just as she comes. It was only a question of light management and largely leaving the place to tell its own story.

What a treat when a subject comes to you in such a complete state that the picture nearly takes itself.

Even better when the subject offers 75 flavors of ice cream.

Especially when every other joint on the block is plain vanilla.

follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

LESS SHOWS MORE

You don’t have to reveal every stray pebble or every dark area in perfect definition to get a sense of texture in this shot. 1/160 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

by MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS A WRONG-HEADED IDEA OUT THERE THAT ALL VISUAL OUTCOMES IN PHOTOGRAPHY SHOULD BE EQUAL. That’s a gob of words, so here’s what I’m getting at: higher ISO sensitivity, post-processing and faster lenses have all conspired, of late, to convince some of us that we can, and should, rescue all detail in even the most constrasty images. No blow-outs in the sky, no mushiness in the midrange, no lost information in the darkest darks. Everything in balance, every iota of grain and pattern revealed.

Of course, that is very seductive. Look at a well-processed HDR composite made from multiple bracketed images, in which the view out the window is deep and colorful, and the shadowy interiors are rich with texture. We’ve seen people achieve real beauty in creating what is a compelling illusion. But, like every other technique, it can come to define your entire output.

It’s not hard to see shooters whose “style” is actually the same effect applied to damn near all they shoot, like a guy who dumps ketchup on everything his wife brings to the table. When you start to bend everything you’re depicting to the same “look”, then you are denying yourself a complete range of solutions. No one could tell you that you always have to shoot in flourescent light, or that deep red is the only color that conveys passion, so why let yourself feel trapped in the habit of using HDR or other processes to always “average out” the tonal ranges in your pictures? Aren’t there times when it makes sense to leave what I will call “mystery” in the undiscovered patches of shadow or the occasional areas of over-exposure?

Letting some areas of a frame remain in shadow actually tamps down the clutter in a busy image like this. 1/60 sec., f/3.2, ISO 100, 35mm.

I am having fun lately leaving the “unknowns” in mostly darker images, letting the eye explore images in which it can NOT clearly make out ultimate detail in every part of the frame. In the mind’s eye, less can actually “show” more, since the imagination is a more eloquent illustrator than any of our wonderful machines. Photography began, way back when, rendering its subjects as painters did, letting light fall where it naturally landed and leaving the surrounding blacks as deep pools of under-defined space. Far from being “bad” images, many of these subtle captures became the most hypnotic images of their era. It all comes down to breaking rules, then knowing when to break even the broken rule as well.

Within this post are two of the latest cases where I decided not to “show it all”. Call it the photo equivalent of a strip-tease. Once you reveal everything, some people think the allure is over. The point I’m making is that the subject should dictate the effect, never the other way around. Someone else can do their own takes on both of these posted pictures, take the opposite approach to everything that I tried, and get amazing results.

There never should be a single way to approach a creative problem. How can there be?

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @thenormaleye.

Related articles

- HDR Under Control is a Thing of Beauty (thewayeyeseesit.com)

IT’S NOT EASY BEIN’ GREEN

This is the desert? A Phoenix area public park at midday. There is a way around the intense glare. 1/500 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm, straight out of the camera.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR YEARS I HAVE BEEN SHOOTING SUBJECTS IN THE URBAN AREAS OF PHOENIX, ARIZONA, trying to convey the twin truths that, yes, there are greenspaces here, and yes, it is possible for a full range of color to be captured, despite the paint-peeling, hard white light that overfills most of our days. Geez, wish I had been shooting here in the days of Kodachrome 25. Slow as that film was, the desert would have provided more than enough illumination to blow it out, given the wrong settings. Now if you folks is new around here, lemme tell you about the brilliant hues of the Valley of the Sun. Yessir, if’n you like beige, dun, brown, sepia or bone, we’ve got it in spades. Green is a little harder to come by, since the light registers it in a kind of sickly, sagebrush flavor….kind of like Crayola’s “green-yellow” (or is it “yellow-green”?) rather than a deep, verdant, top-o-the-mornin’ Galway green.

But you can do workar0unds.

In nearby Scottsdale, hardly renowned for its dazzling urban parks (as opposed to the resort properties, which are jewels), Indian School Park at Hayden and Indian School Roads is a very inviting oasis, built around a curvy, quiet little pond, dozens of mature shade trees that lean out over the water in a lazy fashion, and, on occasion, some decorator white herons. Thing is, it’s also as bright as a steel skillet by about 9am, and surrounded by two of the busiest traffic arteries in town. That means lots of cars in your line of sight for any standard framing. You can defeat that by turning 180 degrees and aiming your shots out over the middle of the pond, but then there is nothing really to look at, so you’re better off shooting along the water’s edge. Luckily, the park is below street level a bit, so if you frame slightly under the horizon line you can crop out the cars, but, with them, the upper third of the trees. Give and take.

There is still a ton of light coming down between the shade trees, however, so if you want any detail in the water or trees at all, you must shoot into shade where you can, and go for a much faster shutter speed….1/500 up to 1/1000 or faster. It’s either that or shoot the whole thing at a small f-stop like f/11 or more. In desert settings you’ve got so much light that you can truly dance near the edge of what would normally be underexposure, and all it will do is boost and deepen the colors that are there. There will still be a few hot spots on projecting roots and such where the light hits, but the beauty of digital is that you can click away and adjust as you go.

It’s not quite like creating greenspace out of nothing, but there are ways to make things plausibly seem to be a representation of real life, and, since this is an interpretive medium, there’s no right or wrong. And the darker-than-normal shadows in this kind of approach add a little warmth and mystery, so there’s that.

It was “yellow-green”, wasn’t it?

Hope that’s not on the final.

(follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye)