EQUATIONS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY CHANGE YOU MAKE IN THE CREATION OF A PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGE also changes every other element of the picture.

You can’t alter a single element in a photo in isolation. Each decision you make is a separate gear, with its own distinctive teeth, and the way those teeth mesh with all the other gears in the photographic equation determines success in the final picture.

As an example, let’s look at sharpness, perhaps the big “desirable” in an image. The term sounds simple, but is, in fact determined by an entire raft of factors, among them:

A) Choice Of Lens. How uniform is the sharpness of your glass? Is it softer at the edges? Completely sharp at smaller apertures? Does it deliver amazing pictures at one setting while causing distortions or inaccuracies at another?

B) Aperture. The most basic predictor of sharpness, whether you scrimped or splurged on Item “A”.

C) Choice Of Autofocus Setting. Are you telling your camera to selectively sharpen a key object in an isolated part of your image, or asking it to provide uniform sharpness across the entire frame?

D) Anti-vibration. On some longer exposures (for example, on a tripod) this feature may actually be costing you sharpness. Protecting your shot against the hand-held shakes is good. Confusing a camera with active Anti-vibe on a stabilized shot may not work out as well.

E) Contrast. Some people believe that the sharpness of lines and textures is actually the viewable distance between light and darkness, that contrast is “sharpness”. Based on what you prefer, other big choices can be affected, such as the decision to shoot in color or black and white.

F) Stability. Deals with everything from how steady you grip a camera to what else besides yourself, from shutter triggering to SLR mirror shifting, can cause measurable vibration, and thus less sharpness.

G) Editing/Processing. This is where miracles occur. Sometimes. Other times, it’s where we try to slap lipstick on a pig.

We could go on, and so could you. And then consider that this quick checklist only deals with sharpness, just a single element, which, in turn, affects every other aspect of your pictures. Photography is a constant juggling act between technique, experience, experiment, and instinct. What you want to show in your images will dictate how much (or how well) you keep all those balls aloft.

TAKING OFF THE TRAINING WHEELS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S HARD TO BE ANGRY WITH ANY TREND THAT MAKES PHOTOGRAPHY MORE DEMOCRATIC, or puts cameras into more hands. Getting more voices in the global conversation of image-making is generally a great things. However, it comes with a price, one which may make many people actually give up or stagnate in their growth as photographers.

We may be killing ourselves, or at least our art, with convenience.

Cameras, especially in mobile devices, have exponentially grown in ease (and acuity) of use over the last fifty years, but they are actually teaching people less and less about what, technically, is happening in the making of an image. The nearly intuitive logic of smaller and easier cameras means that many people, while busily snapping away and producing billions of pictures, are being more and more estranged from any real knowledge of how it’s all being done.

This is a vicious circle, since it guarantees that a greater number of us will be more and more dependent upon our cameras to make the bulk of the creative decisions for us, more obliged to accept what the camera decides to give us. In some very real way, we are being shortchanged by never having had to work with a garbage camera. Let me explain that.

Being forced to do creative work with an unyielding or primitive tool puts the responsibility for (and control of) the art back on the artist. Those who began their shooting careers with limited box cameras understand this already. If you start making pictures with a device that is too limited or “dumb” to do your bidding, then you have to devise work-arounds to get results. That means you learn more about what light does. You learn what ideal or adverse conditions look like. You see what failure is, and begin to dissect what didn’t work for a stronger understanding of what may work next time. You learn to ride a bike without training wheels, and thus never need them.

The dark lobby of New York’s Chrysler building: An extremely challenging setting for low-light photography. I screwed this up on a cosmic scale, but I learned a ton. Shooting on automodes, I would have learned precisely…nothing. And the picture still would have stunk.

The above image, taken on manual settings in a less-than-ideal setting, has about a dozen things wrong with it, but the mistakes are all my mistakes, so they retain their instructive power. If something was blown, I know how it can be corrected, since I’m the one who blew it. There is a clear linear learning process that benefits from making bad pictures. And if my camera had done everything itself and the picture still reeked, then I’d be stuck with both failure and ignorance.

Cameras that remove the risk of failure also remove the chance of accidental discovery. If you always get acceptable images, you’re less likely to ask what lies beyond….what, in effect, could be better. You accept mediocrity as a baseline of quality. And editing tools that consist mostly of corrective solutions, from straightening to sharpening, keep you from addressing those errors in the camera, and that, too, robs you of valuable experience.

Convenience, in any art medium, can either abet or prevent excellence. The amount of curiosity and hunger in the individual is the decisive factor in moving from taking to making pictures. For my money, if you’re going to grind out the process of becoming an artist, you can’t rely on equipment that is designed to protect you from yourself.

THE WANDERING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN ONE OF LIFE’S GREAT IRONIES, YOU TRULY BECOME A PHOTOGRAPHER the first time you consider chucking all your gear off a cliff and never taking a picture again. Just as you can’t understand faith until you nearly lose it, you can’t really become an excellent maker of pictures unless you’ve been paralyzed, even a little frightened, in considering the distance between what you know and what you need to know.

All visual arts, all arts in general, really, are pursuits. We are chasing something, either in our work or in ourselves. Maybe both. We don’t always know what it is, but we sure as hell know what it’s not. Calling forth an image from a mix of instinct, experience and light seems like an easy thing, since there are so many cameras that deliver acceptable pictures with a minimum of effort. Unlike the early days of the medium, it’s no longer an uphill struggle technically getting “a” picture.

Ah, but getting “the” picture…that’s the work of a lifetime.

Sometimes, that challenge seems glorious. A crusade. Other times, it’s a slog. And, occasionally, the wandering between what you see in your head and what you can deliver in a given picture is exhausting, and you will sometimes want to stop. For good. Many do, and many more ache to.

The technical part of photography can certainly be taught, just as there is not that much to the mere mechanics of hitting a baseball or driving a car. Getting to the excellence, however, is daunting. And if you’re hung up on destinations, on “getting there”, realizing that it’s actually about the journey can be heartbreaking. You want to arrive at perfection, and you realize that you never can.

You have to learn to live on little glimpses of the prize, those flickers of wow when an image starts to take on its own life. That’s the payoff. Not praise, or publication, or a million “likes” on Instagram. Because it really doesn’t matter a damn what others think of your work. If you don’t love it, all the applause in the world just becomes noise. The pictures have to be there. For you. The wandering has to amount to something.

Once you learn to find fault in even your favorite brainchildren, you can father better ones going forward. Even better, once you know what your work looks like when you’re lost, the closer you are to being found. Eventually, photography is like anything else you can care passionately about. The fire carries you through when the progress won’t.

So hang on. There’s light up ahead.

Go catch it.

THIS MUST BE / MIGHT BE THE PLACE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS ACT IN MUCH THE SAME WAY AS ARCHAEOLOGISTS in that they must try to supply context for objects, backstories that have been either altered or erased. Cities are collections of things created by humans for specific motives, be it profit, shelter, play, or worship. Often, the visual headstones of these dreams, that is, the buildings, survive beyond the people that called them into being. Photographers have to imply the part of the story that’s crumbled to dust. Like the archaeologist, we try to look at shards and imagine vases, or see an entire temple in a chunk of wall.

During the dreaded “urban renewal” period in the mid-twentieth century, my home town of Columbus, Ohio duplicated the destruction seen in cities across the country in the wanton devastation of neighborhoods, landmarks and linkages in the name of Progress. Today’s urban planners thumb sadly through vast volumes of ill-considered “improvements” wrought upon history from that period, with New York’s Penn Station, Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, and Columbus’ Union Station surviving today only as misty symbols of fashion gone amok.

In the case of Columbus’ grand old railroad station, there is at least a fragment of the original structure, its beaux-arts entry arch, left standing, serving as either stately souvenir or cautionary tale, depending on your viewpoint. The arch has been moved several times since the demolition of its matching complex, and presently graces the city’s humming new hockey and entertainment district, itself a wondrous blend of new and repurposed architecture. Better late than never.

Thus, the Union arch has, by default, become one of the most photographed objects in town, giving new generations of artists permission to widely interpret it, freed, as it is, of its original context. Amateur archaeologists all, they show it as not only what it is, but also what it was and might have been. It has become abstracted to the point where anyone can project anything onto it, adding their own spin to something whose original purpose has been obliterated by time.

I have taken a few runs at the subject myself over the years, and find that partial views work better than views of the entire arch, which is crowded in with plenty of apartment buildings, parklands and foot traffic, making a straight-on photo of the structure busy and mundane. For the above image, I imagined that I had recovered just an old image of the arch….on a piece of ancient parchment, a map, perhaps an original artist’s rendering. I shot straight up on a cloudy day, rendering the sky empty and white. Then I provided a faux texture to it by taking separate a sepia-toned photo of a crumpled piece of copier paper and fusing the two exposures (the HDR software Photomatix’ “exposure fusion” feature does this easily). Letting the detail of the arch image bleed randomly through the crumpled paper picture created a reasonable illusion of a lost document, and I could easily tweak the blend back and forth until I liked the overall effect.

Cities are treasure hunts for photographers, but not everything we find has to be photographed at, let’s say, face value. Reality, like fantasy, sometimes benefits from a little push.

MORE TOOLS IN MORE HANDS

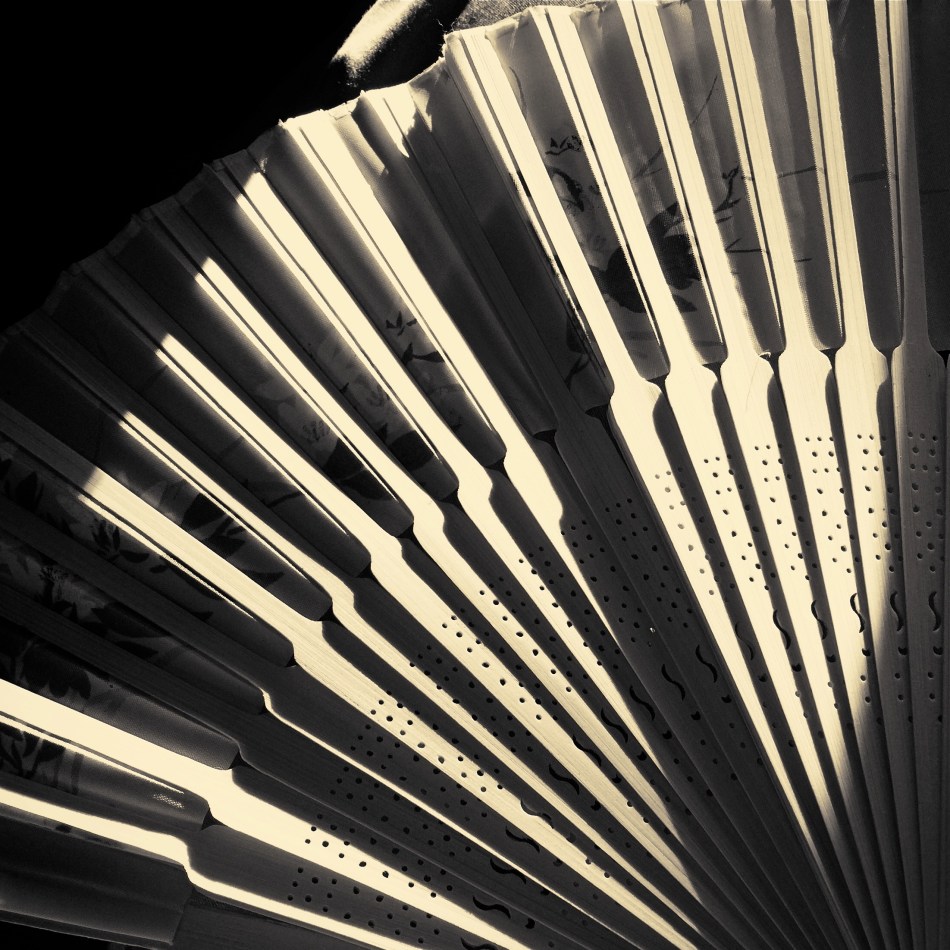

Shot one inch away with Lensbaby macro converters, accessories for the company’s 35mm lens, amazingly priced at about $49.95.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE CELL PHONE CAMERA’S IMPACT ON PHOTOGRAPHY HAS BEEN SO SUDDEN AND FAR-REACHING that its full impact has yet to be fully measured. Within a decade, the act of making a picture has been democratized to a greater degree than at any other time in the history of the medium. It’s as if, overnight, everyone was given the ability to leap tall buildings in a single bound. Goodbye, Superman, hello, Everyman. The Kodak Brownie’s introduction prior to 1900 gave the average human his first camera. The cell phone is like the Brownie on steroids and four shots of Red Bull.

It’s more than just giving millions of people the ability to take a photo. That part had been done before, dozens of times. However, no other camera before the cell has also obliterated the number one obstacle to picture-making on this scale: cost. The cost of film. The cost of marketing and sharing one’s work quickly, and with uniform quality. The cost of artistry, with support apps allowing people to directly translate their vision into a finished product without investing in gear that, just a few years ago, priced most people out of the creative end of the market.

Most significantly, there is the cost saved in time. Time learning a technique. Time speeding past the birth pains of your creative energy. you know, those darn first 10,000 hours of bad pictures that used to take years of endurance and patience. The learning curve for photography, once a gradually arching line, is now a dramatic, vertical jump into the stratosphere.

These insane leaps in convenience and, for the most part, real technical improvement occur across all digital media, but, in the cel phone, their impact is spread across billions, not mere millions, of users. Simulate a particular film’s appearance? Done. Do high-quality macro or fisheye without a dedicated lens running into the hundreds? Yeah, we can do that. Double-exposures, selective focus, miniature effects, pinhole exposures, even remote auxiliary lighting? Go fish. It’s all there.

And when cells raise the ante, traditional cameras have to up their game just to survive. The shot at the top of this page comes from a pair of Lensbaby macro converters up front of the company’s Sweet 35 optic, a shot that would only have come, a few years ago, from a dedicated macro lens costing upwards of $500. Lensbaby’s version? $49.95. And now, with less than a decade in the effects lens biz for DSLRs, Lensbaby makes macro, fisheye and other effect lenses for cells. A rising tide raises all boats.

I could make a list of the areas where the optics and outputs of cell phones are still behind conventional camera optics, but if this post is ever read more than a year past its publication, the future will make a liar out of me. Besides, that would put me on the same side as the carpers who still claim that film is better, more human, or “warm”, as the vinyl LP hipsters like to say. Your horse is nice, but it can’t outrun my Model T.

Part of photography’s appeal since day one has been the knowledge that, whatever era you live in, it’s a sure bet that some geek is slaving away in a lab somewhere, trying to make your sleek, easy, “latest thing” seem slow, clunky and over with. We’re never done. Which means that we’re always just beginning.

Cool.

LEFT, RIGHT, LEFT

Both of the images in this improvised double-exposure were taken within a space of five minutes. Final processing was finished in ten.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN HER BRILLIANT 1979 BEST SELLER DRAWING ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE BRAIN, art teacher Betty Edwards, while obviously addressing the creative process chiefly as it regards graphics, also contributed to a better understanding of the same visualization regimen used by photographers. In its clear explanation of the complementary roles of the brain’s hemispheres in making an image, Ms. Edwards demonstrates that photographs can never be just a matter of chiefly left-brained technique or merely the by-product of unfettered, right-brained fancy.

And that’s important to understand as we grow our approach to our craft over time. It’s ridiculous to imagine that we can make compelling images without a certain degree of left-brained mastery, just as you can’t drive a nail if you don’t know how to hold a hammer. But it’s equally crazy to try to take pictures without the right-brained inspiration that sees the potential in a composition or subject even before the left knows how, technically, it can be achieved. One side problem-solves while the other dreams. One hemisphere is an anchor, a foundation: the other is a helium balloon.

When you develop a plan for your next shoot, selecting the lenses and tools you’ll need, scoping out the best locations, it’s all left brain. But, comes the day of the shoot, your right brain might just fall in love with something that wasn’t in the blueprint, something that just must be dealt with now. Fact is, neither side can hold absolute sway. When you are laboring a long time to get a particular picture, you can almost feel the two hemispheres arguing for control. But all that left-right-left toggling isn’t a bad thing, nor should you expect there to be one clear “winner” in the struggle. The pictures that emerge have to be an agreement, or at least a truce between “how do we do this?” and “why should we do this?”.

I have pictures, such as the one up top here, that I call five-minute wonders, so named because they go very quickly from conception to completion. They are like impulse items in the grocery checkout line. I’ll take some of this, a few of these, and one of those, toss them together in a bowl, and see what happens. Sounds very right-brained, right? However, none of these quickie projects would work if I simply don’t know how to make the camera give me what I want. That’s all left brain. The point is, the two factions must at least have a grudging conversation with each other. Right-brained creativity gets all the chicks and the cool clothes: it’s the flashy rock star of the photo universe, a sexy bad boy who just won’t listen to reason. However, Lefty has to take the wheel occasionally or Righty will crash the sports car and we’ll all die horribly.

It’s romantic to believe that all our great photographs come from blindingly brilliant flashes of pure inspiration. That’s where the lomography movement with its cheap plastic cameras and its “don’t think, shoot” mantra comes from. And impulse certainly plays its part. However, anyone who tells you that amazing images come solely from some bottomless wellspring of the soul is only telling you half the truth. Sometimes you can spend the day playing hooky, and some days you gotta stay inside and do your homework.

Left, right, left….

A TRIAL SEPARATION

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A PERSON’S RELATIONSHIP WITH PHOTOGRAPHY, MEASURED OVER A LIFETIME, can come to resemble a marriage, with all the occasional rifts, rumbles and repellents of living with anyone (or anything) nonstop ’til death. Just as any good golfer has thrown the odd club into the 7th hole lake, any shooter worth his emulsions/pixels will, at least once, consider pitching his gear into the nearest abyss, then setting a cheery bonfire of his accumulated work alight in the home driveway (after securing all necessary permits, of course). I dare you to deny it. We hate intensely because we have loved intensely, and fallen intensely short.

The fury eventually abates, however, and we resume the “on” portion of the on again/off again love of photography, not knowing when it next will toggle to “off”, or if switching back to “on” even has any prospect of success. The fact is, creative passion can generate emotional surges, microbursts of feeling so intense they could pop the top off a seismograph. This means answering “the questions” as they ring inside your skull:

Why did I ever start doing this?

What made me thing I’d ever be any good at it?

And where is that damned lens?????

In the interest of my own sanity, I never contemplate a total divorce from photography, but I avidly support the need for a trial separation from time to time. Every relief valve has to be opened and flushed out occasionally, and when the ideas, or the patience to execute them, seem to have gone south for the winter, you have to furlough the workers and shut down the plant. For a while. Hammering away at a problem with an image may eventually loosen what’s stuck, but it’s just as valuable to know when to lay down your tools and quit the scene. For a while. Once your brain is running on high-octane rage, all things beautiful and visionary will just be drowned out by all the screaming, so, really, I’m not kidding: accept the fact that occasionally you’ll announce to all your friends and family that you’re “over the whole photography thing”. And you will absolutely mean it.

For a while.

Here’s another thought: fake-quitting photography will provide the most severe test of how much you were into it in the first place. A trial separation is just that: a test to see if there was anything worth saving in the relationship. Scary process, but, if you come back, whether to a partner or a Nikon, you come back renewed and freshly committed to Make This Thing Work. All of a sudden, you’re bringing your Canon chocolates and roses, and arranging for a romantic candlelight dinner. And the work grows again.

For a while.

LAYERS OF LEARNING

I have had to change my approach to flowers over a lifetime, and I still don’t “get” them in a real way.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS A YOUNG PIANO STUDENT, I NOTICED THAT MANY OF MY FAVORITE SHORT WORKS all bore the elegant, mysterious name of etude. It was somewhat later that I realized that this was merely the French word for a “study”, and that some of what I regarded as highly developed, final compositions were, essentially, first versions, practice runs by the masters in search of some eventual greatness. And, since I was an illustrator as well as a musician, the idea of an etude as a prototype, a first version of something dovetailed nicely with the idea of a sketch, or as my father called it, a “rough”. An etude was a work in progress.

Then came photography and, with it, the giddy short-term gratification of just snapping a picture, of crossing a visual item off one’s to-do list. We are, as humans naturally attracted to the process of completion, of turning out a finished product. Click. Done. Moving on….However, despite what the auction houses and gallery curators of the world might try to tell you, art is not a product, and just like those melodiously wondrous etudes, the best images are always in the process of being created. You can always take a picture to another level, but you can’t finish it.

Walk across to the painters’ side of the Art building every once in a while and look at how many preliminary studies Leonardo or Michelangelo made of their greatest works, or the number of “early” and “late” versions there are of these same masterpieces. Now, travel back to the photography wing and witness Ansel Adams taking one crack after another at the same stony face of El Capitan, often merely reworking the same master negative up to a half dozen times over decades. You simply have to make different pictures of the same subjects across a lifetime, just because your idea of what’s important to show keeps evolving.

Finally, look objectively at your own output and discover how many of your older images are “good pictures” and how many are good ideas for pictures. You’ll no doubt find your own personal “etudes”, the studies that can still become something better. In my own case, I have to walk away from floral subjects from time to time, then return to approach them with a different mindset, since I’m equally fascinated and clueless as to how to imbue them with anything approaching soulfulness. My eye struggles to make something magical emerge from buds and bouquets as others have done. But I’ll stay at it.

Digital processes make it possible to crank through a wide variety of approaches to the same subject in a very short span of time compared to film-based techniques. Think easy-fast-cheap. Or think good-better-best if you like. Either way, the layers of learning are stacked ever higher and deeper, allowing us to regard photography as process instead of product. So do your scales every day, keep your fingers high and curved, and stay curious.

BOTH ENDS OF FREEDOM

Every camera ever manufactured can make this image, if the right person is behind it. It’s your eye that matters, not your toys.

A camera is a tool for learning how to see without a camera. —Dorothea Lange

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS A REAL DISCONNECT BETWEEN THE “FIRST CAMERAS” OF A GENERATION AGO and those of people just entering the art of photography today. Of course, individual experiences vary, but, in general, people born between 1950 and 1980 first snapped with devices that were decidedly limited as compared to the nearly limitless abilities of even basic gear today. And that creates a similar gap, across the eras, between what skills are native to one group versus the other.

To take one example, if your first camera, decades ago, was a simple box Brownie, the making of your pictures was pretty hamstrung. You had to purposefully labor to compensate for what your gear wouldn’t do. A deliberate plan had to be followed for every shot, since you couldn’t count on the camera to allow for, or correct, your mistakes. With a device that came hardwired with a single aperture, a shutter button, and not much else, you had to be mindful of a whole array of factors that could result in absolute failure. The idea of artistic “freedom” was sought first in knowledge, then, much later, in better equipment.

But if, on the other hand, you begin your photographic development with a camera that, in the present era, is almost miraculously flexible and responsive, freedom is a given. In a sense, it’s also a restraint of a different kind. That is, with bad gear, you’re a hero if you can wring any little bit of magic out of the process. But with equipment that can almost obey your every command, the old “I left the lens cap on”-type excuses are gone, along with any other reason you may offer for not getting at least average results. Thus the under-equipped and the over-equipped have two different missions: one must deliver despite his camera, while the other strives to deliver despite himself.

The entire gist of The Normal Eye is that I believe that even remarkable cameras (and the world is flooded with them) will betray the unseeing eye that mans them. Likewise, the trained eye will create miracles with anything handy. Our thrust here at TNE is toward teaching yourself the complete basics of photography as if you were actually constrained by limited equipment. At the point at which you’ve fully mastered the art of being better than your camera, then, and only then, is it time to get a new camera. Then learn to out-run that one, and so on.

The promise made by cameras today is the same promise that’s always been made by ever-advancing technology, that of wonderful results with minimum effort. It’s the photo equivalent of “eat whatever you want and still lose weight”. But it’s a false promise; photography only becomes art when we ask things of ourselves that our cameras cannot provide by themselves. Anything else is learning to accommodate mediocrity, a world of “pretty good”.

Which, inevitably, is never really good enough.

SO, THAT HAPPENED

Another year older and deeper in depth.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MOST YEAR-END ROUND-UP LISTS, from rosters of hot-selling New York Times books to summaries of the most binge-worthy tv titles, tend, in our marketing-based society, to be “best-of’s”, rankings of what’s hot and what (since it didn’t make the list) is not. I’m certainly not immune to these sales-skewed tabulations, but, in strictly artistic terms, there should also be lists that are more like “most representative of” rather than “best”.

There’s a very human reason for this distinction. Creative people are often fonder of the their personal also-rans than their personal bests. We cherish the effort, as much as, if not more than, the race results. He who came in first and he who gave it the best go are often two different people (or two different works of art), and our hearts go out (especially in the case of our own work) to the stuff that shows our growth rather than our success.

And that’s where I find my head at the end of this photographic year.

Up top of the screen, starting today, there’s a tab for a new gallery page called Fifteen for 15. Now, quickly, guess how many pictures there are in it. Then guess what year they came from. Yeah, I’m really that dull. The images therein aren’t necessarily my technical best, perhaps not even the pictures that work the best for you as an audience. But they do comprise a pretty fair sampling of every direction in which I was attempting to stretch during the year, and maybe that’s more important than a mere brag-sheet of home runs.

I used to think my goal was to develop a style that didn’t, ha ha, look like a style (oh, these artists!) . Now, I actually want to try to create a chronicle of everywhere that I stepped outside my comfort zone, since that’s where both the spectacular wins and the astounding misses reside. And if I can finish out a given calendar year and point to at least a baker’s dozen of shots that show me at least trying to color outside the lines, I’ll call that year a success. With lists, “Best-Of’s” are great for the ego. However, “Representative-Of’s” may be better for the soul.

So, that happened.

EYE ON THE BALL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I CAN STILL HEAR MY LITTLE LEAGUE COACH’S VOICE, cured into a coarse hum by too many years of Lucky Strikes, hitting me in the back of my skull as I stood shakily in the batter’s box. If he had told me once, he had told me a thousand times: don’t try to hit every ball that comes across the plate. You swing like a rusty gate, he would tease me, or don’t eat their garbage. The main message, and one that I only intermittently received: wait for your pitch.

On those rare occasions when I didn’t fish wildly in the air for every single thing that sailed in from the mound, I took great encouragement from his voice saying, good eye. Strangely, I had earned praise for essentially doing nothing, but, hey, I’d take it.

Coach sometimes comes to mind when I view the results of some of my hastier photographic decisions.

There is, for photogs, a very real translation of “wait for your pitch”, and it’s more important in the digital era because it’s such an easy rule to adhere to. Simply, you must keep shooting long enough to get the frame you saw in your mind. There can be no, “I’ve already taken a lot of frames”, or “they’re waiting for me to finish up” or “maybe today’s not my day for this shot.” First of all, it’s your picture. If you want it, take it. Secondly, there is no such thing as “a lot of frames”. There is only enough frames. If clicking one more, hell, ten more, will get you your shot, then do it. There is no phantom film counter warning you that you only have four more Kodachrome exposures left.

I am preaching this particular commandment all too loudly today because I am kicking myself for not living up to it recently. In the top frame, I got every element of a quaint old Amtrak ticket window that appealed to me, including the patterned skylight, the bored agent, the square arrangement of the Deco-ish counter space, and the left and right details of an old archway and a marble wall. Everything except the intrusive passersby on the left. They are sadly out-of-sync with the time-feel of the rest of the shot, and, had I not felt that I had nailed the general exposure and feel of the image, I might have waited for them to move out of frame, and gotten everything I wanted.

But I didn’t. I settled for “close enough”, and moved on to the next subject. Later, in post-production, I could certainly crop my squatters out, but at the cost of the overall composition. I now had to make do with what was left. I managed to reframe for another square shot that included nearly all the same elements. But it was “nearly”, not “all”. And “all” is what I could have had if I hadn’t tried to swing at the wrong ball. You can’t make a good shot out of a bad shot, and when an opportunity is gone, there isn’t a piece of software in the world that can make a miracle out of what’s not in your camera.

Wait for your pitch.

GAS ATTACK

The first-ever cause of Gotta-Getta-Toy disease in my life, the Polaroid Model 95 from 1949. Ain’t it purty?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AT LEAST TWO ACQUAINTANCES HAVE RECENTLY APPROACHED ME, knowing that I shoot with Nikons, to gauge my interest in buying their old lenses. One guy has, over the years, expertly used every arrow in his technical quiver, taking great pictures with a wide variety of glass. He’s now moving on to conquer other worlds. The other, I fear, suffered a protracted attack of G.A.S., or Gear Acquisition Syndrome, the seductive illness which leads you to believe that your next great image will only come after you buy This Awesome Lens. Or This One. Or…

Perk’s Law: the purchase of photographic equipment should be made only as your ability gradually improves to the point where it seems to demand better tools to serve that advanced development. Sadly, what happens with many newbies (and Lord, I get the itch daily, myself) is that the accumulation of enough toys to cover any eventuality is thought to be the pre-cursor of excellence. That’s great if you’re a stockholder in a camera company but it fills many a man’s (and woman’s) closet with fearsome firepower that may or may not ever be (a) used at all or (b) mastered. GAS can actually destroy a person’s interest in photography.

Here’s the pathology. Newbie Norm bypasses an automated point-and-shoot for his very first camera, and instead, begins with a 25-megapixel, full-frame monster, five lenses, two flashes, a wireless commander, four umbrellas and enough straps to hold down Gulliver. He dives into guides, tutorials, blogs, DVDs, and seminars as if cramming for the state medical boards. He narrowly avoids being banished from North America by his wife. He starts shooting like mad, ignoring the fact that most of his early work will be horrible, yet valuable feedback on the road to real expertise. He is daunted by his less-than-stellar results. However, instead of going back to the beginning and building up from simple gear and basic projects, he soon gets “over” photography. Goodbye, son of Ansel. Hello Ebay.

This is the same guy who goes to Sears for a hammer and comes back with a $2,000 set of Craftsman tools, then, when the need to drive a nail arrives, he borrows a two dollar hammer from his neighbor. GAS distorts people’s vision, making them think that it’s the brushes, not the vision, that made Picasso great. But photography is about curiosity, which can be satisfied and fed with small, logical steps, a slow and steady curve toward better and better ways of seeing. And the best thing is, once you learn that,you can pick up the worst camera in the world and make music with it.

There is no shortcut.There are no easy answers. There is only the work. You can’t lose thirty pounds of ugly fat in ten days while eating pizza and sleeping in late. You need to stay after class and go for the extra credit.

THE OTHER TMI

Technical execution here is almost what’s needed, but the concept still needs work. Write the shot off to practice.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE WORST SOCIAL FAUX PAS OF OUR TIME may be the dreaded “TMI”, or the sin of sharing Too Much Information, creating awkward moments by regaling our friends with intimate details of our recent colostomies or carnal conquests. Funny thing is, much as we hate having this badge of uncoolness pinned to our chest, we commit its photographic equivalent all the time, and without a trace of shame.

I’m talking about the other TMI, or Too Many Images.

Let’s face it. Social media has encouraged too many of us to use the Web as a surplus warehouse dump for our photographs, many of them as ill-considered as a teenage girl’s hair flip. We’ve entered an endless loop of shoot-upload-repeat which seldom contains a step labeled “edit”. Worse, the vast storage space in our online photo vaults encourage us to share everything we shoot without so much as a backwards glance.

I’m suggesting that we take steps to stop treating the internet like an EPA Superfund site for images. I have tried to maintain a regular schedule of viewing the rearmost pages of my online archives, stuff from five years ago or longer, learning to ruthlessly rip out the shots that time has proven do not work. The goal is to force myself to re-think my original intentions and make every single photograph earn its slot in my overall profile. There are, by my calculation, three main sub-headings that these duds fall under:

The original idea for this shot is fairly strong, but my execution of it left something to be desired. Like execution.

A bad idea, well executed. Okay, you nailed the exposure and worked the gear to a “T”, but the picture has no story. There’s nothing being communicated or shared. Just because it’s sharp and well-lit doesn’t mean it deserves to stand alongside your stronger work.

A good idea, poorly executed. Hey, if you believe so strongly in the concept, go back and do it right. Don’t give yourself a pass on bad technique because it was a noble effort.

An incomplete idea, which means it wasn’t even time to take the picture at all. Maybe you didn’t know how to get your message across, for whatever reason. Or maybe if you got the conception 100% right, it still wasn’t strong enough to jump off the page. The litmus test is, if you wouldn’t want someone’s random search of your stuff to land on this shot instead of your best one, lose it.

Online stats make some of these tortured choices a bit easier, since, when you are looking at low figures on shots that have been available forever, it’s pretty clear that they aren’t lighting up anyone’s world. And as lame as view and fave counts can be, they are at least an initial signal pointer toward sick cows that need to be thinned from the herd. The cure for photographic “TMI” is actually as easy as shooting for long enough to get better. With a wider body of work viewed over time, the strong stuff stands out in bolder contrast to the weaker stuff. And that shows you where to wield the scissors.

TECHNIQUE OR STYLE?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YEARS OF WRITING DAILY HUMOR MATERIAL FOR OTHERS IN THE RADIO RACKET taught me that comedians fall into two general camps: those who say funny things and those who say things funny. Depending on how you rate writing, your own independence, or even your career longevity, you may opt to be in the first group, flawlessly executing pre-written material, or the second, where the manner in which you put things across allows you to get laughs reading the phone book.

I make this distinction between technique (the gag reciter) and style (the ability to imbue anything with comedy) because photographers must face the exact same choices. Technique helps us deliver the goods with technical precision, to master steps and procedures to correctly execute, say, a time exposure. Style is the ability to stamp our vision on nearly anything we see; it’s not about technical mastery, but internal development. Two different paths. Very different approaches to making pictures.

Obviously, great shooters can’t put their foot exclusively in either camp. Without technique, your work has no level standards or parameters. Lighting, exposure, composition….they all require skills that are as basic as a driver’s-ed class. However, if you merely learn how to do stuff, without having a guiding principle of how to harness those skills, your work will be devoid of a certain soul. Adept but not adorable. This is a trap I frequently find myself falling into, as my shots are a little technique heavy. Result: images that are scientifically sound but maybe a trifle soul-starved. Yeah, I could make this picture, but why did I?

On the style side, of course, you need fancy, whimsy, guts, and, yes, guesswork to produce a masterpiece. However, with an overabundance of unchanneled creativity, your work can become chaotic. Your narrative ability may not be up to the speed of your “vision”, or you may simply lack the wizardry to capture what your eye is seeing. Photographers are, more than anything else, storytellers. If they fail in either grammar or imagination, the whole thing is noise.

Like comics, photographers are both technicians and artists. Even the most seasoned among us needs a touch o’ the geek and a touch of the poet. Anything else is low comedy.

PRACTICE MAKES…?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE BEST SELLER LIST IS THE FASTEST WAY to cement a notion in the public’s mind as indisputable “fact”. We are great at quoting a concept captured in print, then re-quoting the quote, until the “truthfulness” of it becomes plausible. It’s basically a version of the statement, “everybody knows that..” followed by a maxim from whatever hardcover pundit is top in the rotation at a given moment. And it’s about as far from accuracy as you can get.

Ever since pop-psych guru Malcolm Gladwell’s hit book Outliers arrived on shelves a few years back, its main thesis, which is that you need 10,000 hours of practice to become excellent at something, has been trotted out a thousand times to remind everyone to just keep nose to grindstone and, well, practice will make perfect. Gladwell cites Bill Gates’ concentrated stretch of garage tinkering and the Beatles’ months of all-night stands in Hamburg as proof of this fact, and, heck, since it ought to be true, we assume it is.

However, it’s not so true as it is comfortable, and, when it comes to photography, I would never hint that someone could become an excellent artist just by putting in more time shooting than everyone else. If my method is wrong, if I never develop a vision of any kind, or if I merely replicate the same mistakes for the requisite practice period, then I am going to get to my goal older, but not wiser. Time spent, all by itself, is no indication of anything, except time spent. Evolving, constantly learning from negative feedback, and learning how to be your own worst critic are all better uses of the years than just filling out some kind of achievement-based time card.

The perfection of photography is about time, certainly, and you must invest a good deal of it to allow for the mistakes and failures that are inevitable with the acquiring of any skill. But, you must also stir insight, humility, curiosity and daring into the recipe or the end result is just mediocrity. Gladwell’s magical 10,000 hours, a quantity measurement, is only miraculous when coupled with an accompanying quality of work.

There are people who know how to express their soul on their first click of the shutter, just as there are those who slog away for decades and get no closer to imparting anything. It’s how well you learn, not how long you stay in school. It ain’t comforting, but it’s true.

THE EYE BACK OF THE LENS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY YEAR AT THIS TIME, AS I HIT THE RESET BUTTON ON MY LIFE VIA SOME KIND OF BIRTHDAY RITUAL, I pause to wonder, again, whether I’ve really learned anything at all in over fifty years of photography. Surely, by this late date, the habit of shooting constantly should have assured me that I had “arrived” at some place in terms of viewpoint or style, right? And yet, I still feel as if I am just barely inches off the starting line in terms of what there is left to learn, and how much more I need to know about seeing. It’s a great feeling in that it keeps things perpetually fresh, but I often wonder if I’ll ever make it to that mirage I see ever ahead of me.

The aging process, and how that continually remaps your perception, is one of the least pondered areas of criticism as it pertains to photography. And that’s very strange. We track the evolution of technical acuity over a lifetime. We date ourselves in reference to a piece of equipment we acquired, an influential person who crossed our path, or a body of work, but we don’t thoroughly examine how much our photography is being changed completely because the person making the picture is in constant flux. How can we ignore what seems to be the biggest shaper of our vision over time? We don’t even want the same things in an image from one year to the next, so how can we take photos in our maturity anything like those we shot in our youth?

Looking back to my first images, it’s clear that I thought the mere opportunity for a picture plus the act of clicking a shutter would result in a good picture, a kind of “cool view+camera=art” equation. This is to say that, instead of thinking, “I could make a good picture from this”, I was actually thinking, “this would be a good picture.” I know that sounds like hair-splitting of the first order, but the two statements are, in fact, different. The first implies that the camera plus the subject will automatically result in something solid; it’s a snapshot philosophy. The second statement is made by someone who has been frustrated by so many snapshots that he knows he has to step into the process as an active player. That realization can only come with age.

As always, my father’s admonition that art is a process rather than a product emerges as my prime directive. When I look at the pictures made by a twelve-year old me, I can at least see what the little punk was going for, and I can measure whether I’ve gotten any closer to that ideal than he did. The trick is for old me to want it as badly as young me did, and when that happens, I forget how many candles are on the cake, and am just grateful that their light still burns brightly.

ROLL PLAYING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I RECENTLY CAME ACROSS AN ARTICLE IN WHICH A PHOTOGRAPHER BEMOANED the insane volume of images being shot in the digital era. His point was that, while we used to be tightly disciplined in the “budgeting” of shots back in the days of film (in which we had a fixed limit on our shots of 24 or 36 frames), we crank away an infinite number of shots today in short order, many of them near duplicates of each other, flooding the universe with a torrent of (mostly) bad pictures. Apparently, he posits, it is because we can shoot and re-shoot without fear of failure that we make so many mediocre images.

He takes it further, proposing that, as a means of being more mindful in the making of our photos, that we buy a separate memory card and shoot a total of, say, two “rolls” of pics, or 72 total images, forcing ourselves to keep every image, without deletions or retakes, and live with the results for good or ill. I have all kinds of problems with this romantic but basically ill-conceived stunt.

Our illustrious writer and I live on different sides of the street. He seems to believe that the ability to shoot tons of images leads to less mindful technique. I believe the exact opposite.

Not the hardest shot in the world, but in the film era, I might never have guessed how best to nail it. In digital, I was free to approach the right solution over a series of practice shots.

When you are free, via digital photography, to experiment, to correct your errors on the fly, you suddenly have the ability to save more shots, simply because you can close in on the best method for those shots much faster, and at a fraction of the cost, of film. You collapse a learning curve that used to take decades into the space of a few years. One of the things that used to separate great photographers from average ones was the great shooters’ freedom, usually from a financial standpoint, to take more bad (or evolving) images than the average guys could afford to. Of course, really bad photographers can go for years merely continuing to take more and more lousy shots, but the fact is, in most cases, taking more photos means learning more, and, often, eventually making better pictures.

Apparently, our illustrious writer believes that you can only be photographically self-aware if you are constantly reminded how few total frames you’re going to be able to shoot. I truly appreciate the goal of self-reliant, experience-based photography he wants to promote. But I contend that it’s not that we make too many pictures, but that we keep too many. It’s the skill of editing, that unemotional, ice-cold logic in deciding how few of our pictures are “keepers”, that is needed, not some nostalgic longing for the strictures of film.

Hey, of course we over-share too many near-identical frames of our latest ham sandwich. Of course Instagram is as clogged as a sink trap fulla hair with millions of pictures that should never see the light of day. But that’s not because we can shoot pictures too easily. It’s because we don’t grade our output on a stern enough curve. As it gets easier to shoot, it should get tougher to meet muster.

GET THEE TO A LABORATORY

by MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHIC SUBJECT MATTER, ONCE YOU’VE TRAINED YOURSELF TO SPOT IT, is always in ready supply. But, let’s face it: many of these opportunities are one-and-done. No repeats, no returns, no going back for another crack at it. That’s why, once you learn to make pictures out of almost nothing, it’s like being invited to a Carnival Cruise midnight buffet to find something that is truly exploding with possibilities, sites that actually increase in artistic value with repeat visits. I call such places “labs” because they seem to inspire an endless number of new experiments, fresh ways to look at and re-interpret their basic visual data.

My “labs” have usually been outdoor locations, such as Phoenix’ Desert Botanical Gardens or the all-too-obvious Central Park, places where I shoot and re-shoot over the space of many years to test lenses, exposure schemes, techniques, or, in the dim past, different film emulsions. Some places are a mix of interior and exterior and serve purely as arrangements of space, such as the Brooklyn Museum or the Library of Congress, where, regardless of exhibits or displays, the contours and dynamics of light and form are a workshop all in themselves. In fact, some museums are more beautiful than the works they house, as in the case of Guggenheim in NYC and its gorgeous west coast equivalent, The Getty museum in Los Angeles.

No color? No problem. Interior view of the Getty’s visitor center. 1/640 sec., f/5.6. ISO 100, 35mm.

Between the gleaming white, glass-wrapped buildings of this enormous arts campus and its sinuous, sprawling gardens (not to mention its astounding hilltop view), the Getty takes one complete visit just to get yourself visually oriented. Photographically, you will find a million isolated tableaux within its multi-acre layout upon subsequent trips, so there is no end to the opportunities for exploring light, scale, abstraction, and four full seasons of vibrant color. Not a color fan? Fine. The Getty even dazzles in monochrome or muted hues. It’s like Toys ‘R’ Us for photogs.

I truly recommend laying claim to a laboratory of your own, a place that you can never truly be “finished with”. If the place is rich enough in its basic components, your umpteenth trip will be as magical as your first, and you can use that one location as a growth graph for your work. Painters have their muses. Shooter Harry Calahan made a photographic career out of glorifying every aspect of his wife. We all declare our undying love for something.

And it will show in the work.