JUST SAY THANK YOU

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PICTURES HAPPEN WHEN YOU’RE OUT TRYING TO TAKE “OTHER” PICTURES. Pictures happen when you didn’t feel like taking any pictures at all. And, occasionally, the planets align perfectly and you hold something in your hand, that, if you are honest, you know you had nothing to with.

Those are the pictures that delight and haunt. They happen on off-days, against the grain of whatever you’d planned. They crop up when it’s not convenient to take them, demanding your attention like a small insistent child tugging at your pants leg with an urgent or annoying issue. And when they call, however obtrusively, however bothersome, you’d better listen.

Don’t over-think the gift. Just say thank you….and stay open.

This is an overly mystical way of saying that pictures are sometimes taken because it’s their time to be taken. You are not the person who made them ready. You were the person who wandered by, with a camera if you’re lucky.

I got lucky this week, but not with any shot I had set out on a walkabout to capture. By the time I spotted the scene you see at the top of this post, I was beyond empty, having harvested exactly zip out of a series of locations I thought would give up some gold. I couldn’t get the exposures right: the framing was off: the subjects, which I hoped would reveal great human drama, were as exciting as a bus schedule.

I had just switched from color to monochrome when I saw him: a young nighthawk nursing some eleventh-hour coffee while poring over an intense project. Homework? A heartfelt journal? A grocery list? Who could tell? All I could see, in a moment, was that the selective opening and closing of shades all around him had given me a perfect frame, with every other element in the room diffused to soft focus. It was as if the picture was hanging in the air with a big neon rectangle around it, flashing shoot here, dummy.

My subject’s face was hidden. His true emotion or state of mind would never be known. The picture would always hide as much as it revealed.

Works for me. Click.

Just like the flicker of a firefly, the picture immediately went away. My target shifted in his chair, people began to walk across the room, the universe changed. I had a lucky souvenir of something that truly was no longer.

I said thank you to someone, packed up my gear, and drove home.

I hadn’t gotten what I originally came for.

Lucky me.

related articles:

- Crop and turn a bad picture into a good one (weliveinaflat.wordpress.com)

FRAGMENTING THE FRAME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE MADE A CONSCIOUS EFFORT, IN RECENT YEARS, TO AVOID TAKING A “STRAIGHT SHOT” OUT OF, OR THROUGH A WINDOW, of using that rectangle or square as a conventional means of bordering a shot. Making a picture where a standard view of the world is merely surrounded by a typical frame shows my eye nothing at all, whereas the things that fragment that frame, that break it into smaller pieces, bisecting or even blocking information…..that’s fascinating to me.

This is not an arbitrary attempt to be “arty” or abstract. I simply prefer to build a little mystery into my shots, and a straight out-the-window framing defeats that. My showing everything means the viewer supplies nothing of his own. Conversely, pictures that both reveal and conceal, simultaneously, invite speculation and encourage inquiry. It’s more of a conversation.

Think about it like a love scene in a movie. If every part of “the act” is depicted, it’s not romantic, not sexy. It’s what the director leaves out of the scene that fires the imagination, that makes it a personal creation of your mind. Well-done love scenes let the audience create part of the picture. Showing everything is clinical….boring.

With that in mind, The Normal Eye’s topside menu now has an additional image gallery called Split Decisions, featuring shots that attempt to show what can result when you deliberately break up the normal framing in and out of windows. Some of the shots wound up doing what I wanted: others came up short, but may convey something to someone else.

As always, let us know what you think, and thanks for looking.

Related articles

- Framing Framing Framing!!! (destynimcbeth.wordpress.com)

GOING OFF-MENU

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I AM ALREADY ON RECORD AS A CHAMPION OF THE ODD, THE OFF-KILTER, AND THE JOYFULLY STRANGE IN AMERICAN RETAIL. As a photographer, I often weep over the endangered status of the individual entrepreneur, the shopkeeper who strikes out in search of a culturally different vibe, some visual antidote to the tsunami of national chains and marts that threatens to drown out our national soul. Sameness and uniformity is a menace to society and a buzzkill of biblical proportions for photography. Art, like nature, abhors a vacuum.

It is, of course, possible that someone might have created a deathless masterpiece of image-making using a Denny’s or a Kohl’s as a subject, and, if so, I would be ecstatic to see the results, but I feel that the photog’s eye is more immediately rewarded by the freak start-ups, the stubborn outliers in retail, and nowhere is this in better evidence than in eateries. Restaurants are like big sleeves for their creators to wear their hearts on.

The surf is seldom “up” at the Two Hippies’ Beach House Restaurant in Phoenix, AZ, but the joint is “awash” in mood. 1/640 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 18mm.

That’s why this divinely misfit toy of a diner, which was hidden in plain sight on one of the main drags in central Phoenix, has given me such a smile lately. I have never eaten at the swelegant Two Hippies’ Beach House, but I have visually feasted on its unabashed quirkiness. And if the grub is half as interesting as the layout, it must be the taste equivalent of the Summer of Love.

Even if the food’s lousy, well, everyone still gets a B+ anyway for hooking whoever is induced to walk in the door.

On the day I shot this, the midday sun was (and is) harsh, given that it’s, duh, Arizona, so I was tempted to use post-processing to even out the rather wide-ranging contrast. Finally, though, I decided to show the place just as I discovered it. Amping up the colors or textures would have been overkill, as the joint’s pallette of colors is already cranked up to 11, so I left it alone. I did shoot as wide as I could to get most of the layout in a single frame, but other than that, the image is pretty much hands-off.

Whatever my own limited skill in capturing the restaurant, I thank the photo gods for, as the old blues song goes, “sending me someone to love.”

Trippy, man.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

TAKE WHAT YOU NEED AND LEAVE THE REST

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LOOKING OVER MY LIFETIME “FAIL” PHOTOGRAPHS, FROM EARLIEST TO LATEST, it’s pretty easy to make a short list of the three main problems with nearly all of them, to wit:

Too Busy.

Too Much Stuff Going On.

I Don’t Know Where I’m Supposed To Be Looking.

Okay, you got me. It’s the same problem re-worded three ways. And that’s the point, not only with my snafus but with nearly other picture that fails to connect with anybody, anywhere. As salesmen do, photographers are always “asking for the order”, or, in this case, the attention of the viewer. Often we can’t be there when our most earnest work is seen by others. If the images don’t effectively say, this is the point of the picture, then we haven’t closed the deal.

It’s not simple, but, yeah, it is that simple.

If we don’t properly direct people to the main focus of our story, then we leave our audiences wandering in the woods, looking for a way out. Is it this path? Or this one?

In our present era, where it’s possible to properly expose nearly everything in the frame, we sometimes lose a connection to the darkness, as a way to cloak the unimportant, to minimize distraction, to force the view into a succinct part of the image. Nothing says don’t look here like a big patch of black, and if we spend too much time trying to show everything in full illumination, we could be throwing away our simplest and best prop.

Let sleeping wives lie. Work the darkness like any other tool. 1/40 sec., f/1.8, ISO 1250 (the edge of pain), 35mm.

In the above picture of my beautiful Marian, I had one simple mission, really. Show that soft sleeping face. A little texture from the nearby pillows works all right, but I’m just going to waste time and spontaneity rigging up a tripod to expose long enough to show extra detail in the chair she’s on, her sweatshirt, or any other surrounding stuff, and for what? Main point to consider: she’s sleeping, and (trust me) sleeping lightly, so one extra click might be just enough to end her catnap (hint: reject this option). Other point: taking extra trial-and-error shots just to show other elements in the room will give nothing to the picture. Make it a snapshot, jack up the ISO enough to get her face, and live with the extra digital noise. Click and done.

For better or worse.

Composition-wise, that’s often the choice. If you can’t make it better, for #%$&!’s sake don’t make it worse.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

THE INVISIBLE ARMIES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WE LEARN, OVER A LIFETIME, NOT TO SEE THEM. The sweepers, the washers, those who clean up, clear away and reassemble our daily environment. They are hidden in plain sight, these silent crews of keepers and caretakers. They are the reason there are towels in the restrooms, liners in the trash bins, forks on the table. A silent machine of constantly moving gears readies our way in so many unseen ways each days, tended by the invisible armies of our cities.

They start early, finish late, glide by silently, and move on to the next task. Busy as we are, once we first hold a camera, they are stories dying to be revealed, wondered at, worried over.

The unnamed lady at the broom in the above image came into my view just because I had chosen, at a particular moment, to cross the window side of the second floor of a bookstore. Framed naturally between a giant rooftop sign and a tree, she was served up as a ready-made subject for me, and would have been completely unseen had I not visited the store at the very moment it opened.

The invisible armies roll in and out, like some silent tide, and their work is usually done before we crank up our day. Their world and ours can dovetail briefly, but in large part we occupy difference spaces in time. I love catching people in the act of prepping the morning.

The best images are the ones you dig for a bit.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

MAKING THE MIRACLES MUNDANE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

GIVEN OUR USUAL HUMAN PROPENSITY FOR USING PHOTOGRAPHY AS A LITERAL RECORDING MEDIUM, most of our pictures will require no explanation. They will be “about” something. They will look like an object or a person we have learned to expect. They will not be ambiguous.

The rest, however, will be mysteries…..big, uncertain, ill-defined, maddening, miraculous mysteries. Stemming either from their conception or their execution, they may not immediately tell anyone anything. They may ring no familiar bells. They may fail to resemble most of what has gone before. These shots are both our successes and failures, since they present a struggle for both our audiences and for ourselves. We desperately want to be understood, and so it follows that we also want our brainchildren to be understood as well. Understood…and embraced.

It cannot always be, and it should not always be.

No amount of explanatory captioning, “backstory” or rationalization can make clear what our images don’t. It sounds very ooky-spooky and pyramid- power to say it, but, chances are, if a picture worked for you, it will also work for someone else. Art is not science, and we can’t just replicate a set of coordinates and techniques and get a uniform result.

There is risk in making something wonderful….the risk of not managing to hit your mark. It isn’t fatal and it should not be feared. Artistic failure is the easiest of all failures to survive, albeit a painful kick in the ego. I’m not saying that there should never be captions or contextual remarks attached to any image. I’m saying that all the verbal gymnastics and alibis in the world won’t make a space ship out of a train wreck.

The above image is an example. If this picture does anything for you at all, believe me, my explanation of how it was created will not, repeat, not enhance your enjoyment of it one particle. Conversely, if what I tried is a swing and a miss, in your estimation, I will not be able to spin you a big enough tale to see magic where there is none. I like what I attempted in this picture, and I am surprisingly fond of what it almost became along the way. That said, I am perfectly fine with you shrugging your shoulders and moving on to the next item on the program.

Everything is not for everybody. So when someone sniffs around one of your photographs and asks (brace for it), “What’s that supposed to be?”, just smile.

And keep taking pictures.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

Related articles

- Weakness as Potential Strength (munchow.wordpress.com)

- Hidden Surprises in the Mundane (piconomy.wordpress.com)

ON THE ROAD TO FINDOUT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LATELY I’VE TAKEN TO GRABBING LYRICS OR TITLES FROM POP SONGS TO SUM UP WHAT I WANT TO SAY IN A GIVEN POST, and apparently I haven’t yet kicked the habit. Like the searcher in Cat Stevens’ early ’70’s tune, I am sure that (a) I don’t really know where I’m going most of the time, and (b) the place I’m eventually going to will explain all, eventually. Pretty sunny outlook for a burned out old flower child, I’ll admit, but, especially in photography, the journey is the quest. What we encounter “on the road to findout” is worth the price of the trip.

That’s a fancy-pants way of saying that, frequently when I’m on a photo walkabout, I only think I know what I’m looking for. Sometimes I actually snag the object of the expedition, then find that it’s as disappointing as winning that cheap plush toy that looked so wonderful behind the carnival barker’s counter. Such a thing happened this week, when I drove five miles out of my way to revisit a building that had grabbed my attention several months prior. Short term result: mission accomplished…building located and shot. Long term result: what did I think that was going to be? Ugh.

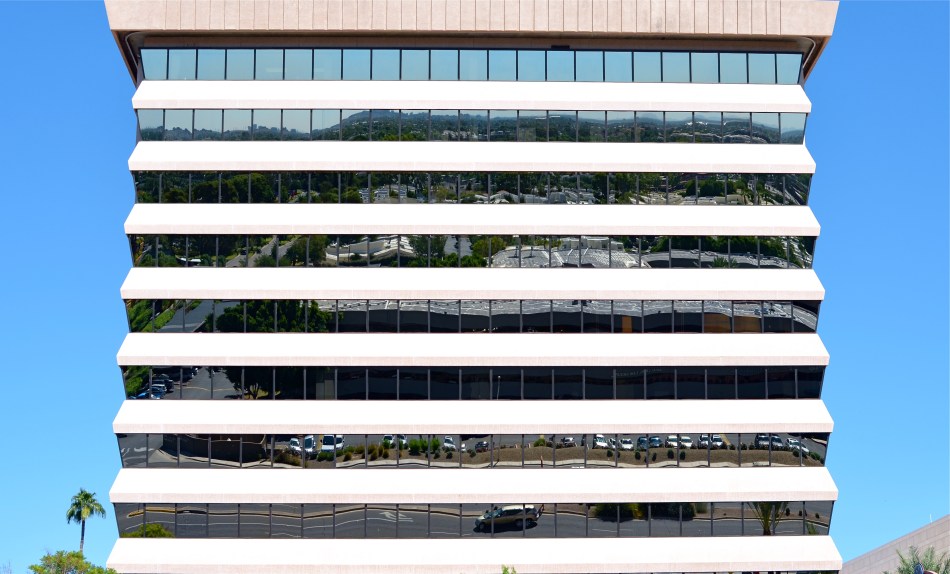

I was walking off my mild disappointment, heading back to my car, and then the mundane act of stowing my camera forced me to rotate my gaze just far enough to see what the midday light was doing to the building across the street. It’s masses of glass looks rather flat and dull by morning, but, near noon, it becomes a slatted mirror, kind of a giant venetian blind, reflecting the entire street scene below and across from itself. The temporary light tilt transforms the place into a surreal display space for about thirty minutes a day, and, had I not been standing exactly where I was across the street at that moment, I would have missed it, and missed the building as a subject for the next, oh, 1,000 years.

Kurt Vonnegut had a dear friend from Europe who always parted from him by hoping that they would meet again in the future if the fates allowed. Only the idiom got crumpled a little in translation, coming out as “if the accident will”. Vonnegut loved that, and so do I.

On the road to findout, we may take wonderful pictures.

If the accident will.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

CUE THE CUMULUS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AMERICA’S SOUTHWESTERN STATES COME EQUIPPED WITH SOME OF THE MOST SPECTACULAR SCENERY TO BE HAD ANYWHERE ON EARTH; jutting crags, yawning canyons, vast valleys, and more sky than you’ve ever seen anywhere. Photographically, the mountains, mesas and arroyos deliver on drama pretty much year-round, while the sky can be an endless expanse of, well, not much, really. Compositionally, this means rolling the horizon line in your framing pretty far toward the top, crowding out a fairly unbroken and featureless ocean of blue….except for more humid summer months, when cloud formations truly steal the scene.

It’s true: as the storm season (sometimes called the “monsoon”, for reasons that escape me) accompanies the year’s highest temperatures in desert regions, rolling, boiling billows of clouds add texture, drama, even a sense of scale to skies in Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and California. It’s like getting free props for whatever photographic theatre you care to stage, and it often makes sense to rotate your horizon line back toward the bottom of the frame to give the sky show top billing.

Early photographers often augmented the skies in their seascapes and mountain views by layering multiple glass negatives, one containing ground features, the other crammed with “decorator” clouds. The same effect was later achieved in the darkroom during the film era. Hey, any way you get to the finish line. Suffice it to say that the harvest of mile-high cloud banks is particularly high in the desert states’ summer seasons, and can fill the frame with enough impact to render everything else as filler.

I still marvel at the monochrome masterpiece by Life magazine’s Andreas Feininger, Texaco Station, Route 66, Seligman, Arizona, 1947, which allows the sky overhead to dwarf the photo’s actual subject, creating a marvelous feeling of both space and scale. I first saw this photo as a boy, and am not surprised to see it re-printed over the decades in every major anthology of Life’s all-time greatest images. It’s a one-image classroom, as all the best pictures always are. For more on Feininger’s singular gift for composition, click the “related articles” link below.

Big Sky country yields drama all along the America southwest. And all you really have to do is point.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

Related articles

- Photography Monograph (conordoylephoto.wordpress.com)

TAKING / BRINGING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

INTELLECTUALLY, I KNOW THAT PHOTOGRAPHS DON’T NECESSARILY HAVE TO BE “ABOUT”, well, anything, but that doesn’t stop the 12-year-old photo newbie deep inside me from trying to produce images with “meaning” (yawn). Some reason to look. A subject. A story line. A deliberate arrangement of things for the purpose of communicating…something. Itchy and twitchy within my artist’s skin as I always am, I am never more out of my element than when I make a picture that is pure composition and form, a picture that has no reason to exist except that I wish it to.

As I get older, I get looser (no G.I. tract jokes about the elderly, please), and thus making what you might call “absolute” images gets easier. I just had to learn to give myself permission to do them. Unlike Atget, Brassai, and half a dozen early pioneering photographers, I don’t have to take pictures to earn my bread, so, if I capture something that no one else “gets” or likes, my children will not starve. Still, the act of making photographs that carry no narrative is far from native to me, and, if I live to be 125, I’ll probably learn to relax and really do something okay by about 93.

The process can be a head-scratcher.

The above image is an “absolute” of sorts, since I have no emotional investment whatever in the subject matter, and have nothing to reveal about it to anyone else. The arbitrary and somewhat sterile symmetry of this room, discovered during a random walk through a furniture store, just struck me, and I still cannot say why. Nor can I explain why it scores more views on Flickr over some of my more emotional work by a margin of roughly 500 to 1. A whole lot of people are seeing something in this frame, but I suspect that they are all experiencing something different. They each are likely taking vastly varied things from it, and maybe they are bringing something to it as well. Who knows what it is? Sense memory, a fondness for form or tone, maybe even a mystery that is vaguely posed and totally unresolved.

“Even though there are recognizable objects making up the arrangement, the result is completely abstract.There isn’t a “human” story to tell here, since this room has never been inhabited by humans, except for wandering browsers. It has no history; nothing wonderful or dreadful ever happened here. In fact, nothing of any kind ever happened here. It has to be form for its own sake; it has no context.

I liked what happened with the very huge amount of soft window light (just out of frame), and I thought it was best to render the room’s already muted tones in monochrome (it wasn’t a big leap). Other than that, it would be stupid to caption or explain anything within it. It is for bringers and takers, bless them, to confer meaning on it, if they can. As I said earlier, it’s always a little scary for me to let go of my overbrain when making a picture.

Then I remember this is supposed to be about feeling as well as thinking.

***Deep breath***

Next.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

Related articles

- First Critique (cohensrphotography.wordpress.com)

SECOND SIGHT, SECOND LIFE

Pragmatically “useless” but visually rich: an obsolete flashbulb glows with window light. 1/80 sec., f/5.6, ISO 640, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A DECADE-AND-A-HALF INTO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY, we are still struggling to visually comprehend the marvels of the twentieth. As consumers, we race from innovation to innovation so amazingly fast that we scarcely apprehend the general use of the things we create, much less the underlying aesthetic of their physical forms. We are awash in the ingenuity of vanishing things, but usually don’t think about them beyond what we expect them to supply to our lives. We “see” what things do rather than seeing their essential design.

As photographers, we need not only engage the world as recorders of “reality” but as deliberate re-visualizers of the familiar. By selecting, magnifying, lighting and composing the ordinary with a fresh eye, we literally re-discover it. Second sight gives second life, especially to objects that have outlasted their original purpose. No longer needed on an everyday basis, they can be enjoyed as pure design.

And that’s exciting for anyone creating an image.

The above shot is ridiculously simple in concept. Who can’t recognize the subject, even though it has fallen out of daily use? But change the context, and it’s a discovery. Its inner snarl of silvery filaments, designed to scatter and diffuse light during a photoflash, can also refract light, break it up into component colors, imparting blue, gold, or red glows to the surrounding bulb structure. Doubling its size through use of “the poor man’s macro”, simple screw-on magnifying diopters ahead of a 35mm lens, allows its delicate inner detail to be seen in a way that its “everyday” use never did. Shooting near a window, backed by a non-reflective texture, allows simple sculpting of the indirect light: move a quarter of an inch this way or that, and you’ve dramatically altered the impact.

The object itself, due to the race of time, is now “useless”, but, for this little tabletop scene, it’s a thing made beautiful, apart from its original purpose. It has become something you can make an image from.

Talk about a “lightbulb moment”….

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

Related articles

- “A Sight Into My Photographic Mind” (Perspective) (mrphotosmash.wordpress.com)

HOLDING BACK

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE MIND WANTS TO PAINT ITS OWN PICTURES, and often responds better to art that veils at least part of its message in mystery. The old vaudeville adage, “always leave them wanting something” is especially applicable in the visual arts, where, often as not, the less you show, the better it connects with the viewing public. It’s precisely because you didn’t show everything that your work may reach deeper into people’s imaginations, which are then invited to “partner” in providing what you merely suggested.

This is why radio created more personal “pictures” than television, why an abstract suggestion of on-screen romance is more erotic than full-on depiction of every physical mechanic of an encounter, and why, occasionally, deciding to hold back, to withhold “full disclosure” can create an image that is more compelling because its audience must help build it.

Given the choice between direct depiction of an object and referential representation of it in a reflection or pool of water, I am tempted to go with the latter, since (as is the stated goal of this blog) it allows me to move from taking a picture to making one. Rendering a picture of a tree is basically a recording function. Framing a small part of it is abstraction, thus an interpretive choice. And, as you see above, showing fragments of the tree in a mosaic of scattered puddles gives the viewer a chance to supply the remainder of the image, or accept the pattern completely on its own merits. Everyone can wade in at a level they find comfortable.

I don’t always get what I’m going for with these kind of images, but I find that making the attempt is one of the only ways I can flex my muscles, and ask more of the viewer.

It’s the kind of partnership that makes everything worthwhile.

(follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye)

Check out the excellent minds of our newest followers:

http://www.en.gravatar.com/insideoutbacktofront

PARADOX

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY SET OF VISUAL ELEMENTS, CAPTURED AT OPPOSITE EXTREMES, DELIVERS A COMPLETELY DIFFERENT SET OF STORY RESULTS. For photographers, the everlasting tug-of-war, involving “what to shoot?” is usually between “how close” and “how far away”? Even the lenses we buy, along with their unique properties, reflect this struggle between the intimate tale, told by a close-up, versus the saga, drawn from a vast panorama. There is a season, turn turn turn, for all kinds of image-making, and it’s no great revelation that many shooters can look at the same grouping of components and get remarkably different results.

Had I come upon the cluster of office cubicles seen in the image above on, say, day “A”, I might have been inclined to move in close, for a personal story, a detailed look at Life In The Office In This Modern World, or how worker #3456 left behind his umbrella and half a tuna sandwich. As it turned out, however, it was day “B”, and instead I saw the entire block of spaces as part of an overall pattern, as a series of lives linked together but separate, resulting in the more general composition shown here. I was shooting wide open at f/1.8 to retrieve as much light, handheld, as quickly as possible, to use the surrounding darkness to frame all the visual parts of the scene as boxes-within-boxes, rather than a single cube that warranted special attention.

Next time I’m up to bat with a similar scene, I could make the completely opposite decision, which is not a problem, because there never is a wrong decision, only (usually) wrong execution. And, yes, I realize that, by shooting empty offices, I dodged the whole ethical bullet of “should I be spying on all these people?”, otherwise known as Street Photographers’ Conundrum # 36.

I love wrestling with the paradox of how close, how far. There can be no decisive solution.

Only the fun of the struggle.

Welcome to our newest followers. Check their work out at :

http://www.en.gravatar.com/glennfolkes85

THE WOMAN IN THE TIME MACHINE

by MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE TIMES WHEN A CAMERA’S CHIEF FUNCTION IS TO BEAR WITNESS, TO ASSERT THAT SOMETHING FANTASTIC REALLY DID EXIST IN THE WORLD. Of course, most photography is a recording function, but, awash in a sea of infinite options, it is what we choose to see and celebrate that makes an image either mundane or majestic.

And then sometimes, you just have the great good luck to wander past something wonderful. With a camera in your hand.

The New York Public Library’s main mid-town Manhattan branch is beyond magnificent, as even a casual visit will attest. However, its beauty always seems to me like just “the front of the store”, a controlled-access barrier between its visually stunning common areas and “the good stuff” lurking in untold chambers, locked vaults and invisible enclaves in the other 2/3 of the building. I expect these two worlds to be forever separate and distinct, much as I don’t expect to ever see the control room for electrical power at Disneyland. But the unseen fascinates, and recently, I was given a marvelous glimpse into the other side at the NYPL.

A recent exhibit of Mary Surratt art prints, wall-mounted along the library’s second-floor hall, was somehow failing to mesmerize me when, through a glass office window, I peeked into a space that bore no resemblance whatever to a contemporary office. The whole interior of the room seemed to hang suspended in time. It consisted of a solitary woman, her back turned to the outside world, seated at a dark, simple desk, intently poring over a volume, surrounded by dark, loamy, ceiling-to-floor glass-paneled book shelves along the side and back walls of the room. The whole scene was lit by harsh white light from a single window, illuminating only selective details of another desk nearer the window, upon which sat a bust of the head of Michelangelo’s David, an ancient framed portrait, a brass lamp . I felt like I had been thrown backwards into a dutch-lit painting from the 1800’s, a scene rich in shadows, bathed in gold and brown, a souvenir of a bygone world.

I felt a little guilty stealing a few frames, since I am usually quite respectful of people’s privacy. In fact, had the woman been aware of me, I would not have shot anything, as my mere perceived presence, however admiring, would have felt like an invasion, a disturbance. However, since she was oblivious to not only me, but, it seemed, to all of Planet Earth 2013, I almost felt like I was photographing an image that had already been frozen for me by an another photographer or painter. I increased my Nikon’s sensitivity just enough to get an image, letting the light in the room fall where it may, allowing it to either bless or neglect whatever it chose to. In short, the image didn’t need to be a faithful rendering of objects, but a dutiful recording of feeling.

How came this room, this computer-less, electricity-less relic of another age preserved in amber, so tantalizingly near to the bustle of the current day, so intact, if out of joint with time? What are those books along the walls, and how did they come to be there? Why was this woman chosen to sit at her sacred, private desk, given lone audience with these treasures? The best pictures pose more questions than they answer, and only sparingly tell us what they are “about”. This one, simply, is “about” seeing a woman in a time machine. Alice through the looking-glass.

A peek inside the rest of the store.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

Thanks to THE NORMAL EYE’s latest follower! View NAFWAL’s profile and blog at :

CAUGHT IN THE CROSSFIRE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE HAS BEEN A LOT OF MENTION, OF LATE, OF THE PHENOMENON KNOWN AS “PHOTOBOMBING“, the accidental or intentioned spoiling of our perfect Kodak moments by persons inserted into the frame at a crucial instant. Whether they block the bride’s face, eclipse Grandma’s beloved puppy, or merely pop up annoyingly behind the cute couple, they, and the images they ruin, are one of the hottest posting sources along the photo-internet galaxy right about now.

But fate photobombs us every day, and often drops a gift out of the sky, and into our pictures. The two-fold trick is to (a) be ready to improvise and (b) be grateful for the chance for something altogether different from what we originally conceived.

Happened to me several weeks ago. Total accident, since the thing I shot in the moment was not what I had started out for at all. Real simple situation:an underground walkway from one low-lying section of a city park to another, the sidewalk taking a short cut under a bridge. Overhead, six lanes of unheeding street-level traffic. Below, a concrete tunnel of sorts, with sunlight from the park illuminating either open end.

Oh, and the grate. Should mention that a section of the street overhead was, instead of solid roadbed, an open-pattern, structural steel grid, with dappled geometrics of light throwing a three-sided pattern of latticed shadows onto the side walls and floor of the tunnel below. Nice geometry. Now, I wasn’t looking to shoot anything down here at all. Like the chicken, I just wanted to get to the other side. But I had my wide-angle on, and a free light pattern is a free light pattern. One frame. A second, and then the bomb: a jogger, much more acquainted with this under-the-road shortcut than me, crossing from over my right shoulder and into my shot. Almost instinctively, I got her in frame, and relatively sharp as well.

Same settings as in the “jogger” frame, but a little colder minus the human element. A matter of taste.

Not content to have caught the big fish of the day, I took the opposite angle and tried again to recoup my “ideal shot”, minus the human element. But something had changed. Even so, I still needed a gentle nudge from Fate to accept that I had already done as well as I was going to do.

My battery died.

I limped home, then, during my upload, found that what I had been willing to reject had become essential. I wish it was the first time I’ve had to be taught this lesson.

But I’d be lying.

Photobombed by circumstance.

And grateful for it.

follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

THE GRADUAL REVEAL

by MICHAEL PERKINS

CREATING FANTASY IMAGES ON A TABLETOP IS A LITTLE LIKE WATCHING YOUR GRANDMA IN THE KITCHEN, if your grandma (like mine) was the “I-don’t need-no-recipe”,a dash here, a pinch there kind of cook. Sometimes I think she just kept chucking ingredients into the pot until it was either the right color or the correct thickness. All I know is, when she was done, it “ate pretty good”.

I use the same approach when I am building compositions from scratch. You’re not sure what the proportions are, but you kind of know when you’re done.

One of the photo sharing sites that I recommend most enthusiastically is called UTATA, a site which promotes itself as “tribal photography” since it require a certain level of communal kick-in from all its members, posing workshop assignments and themes that take you beyond merely posting your faves. Operating in tandem with its self-named Flickr group, UTATA is about taking chances and forcing yourself, often on a deadline, to see in new ways. If it sounds like homework, it’s not, and even if you have no time to work the various challenges, you’ll still reap a vast wealth of knowledge just riffing through other people’s work. Give it a look at http://www.utata.org.

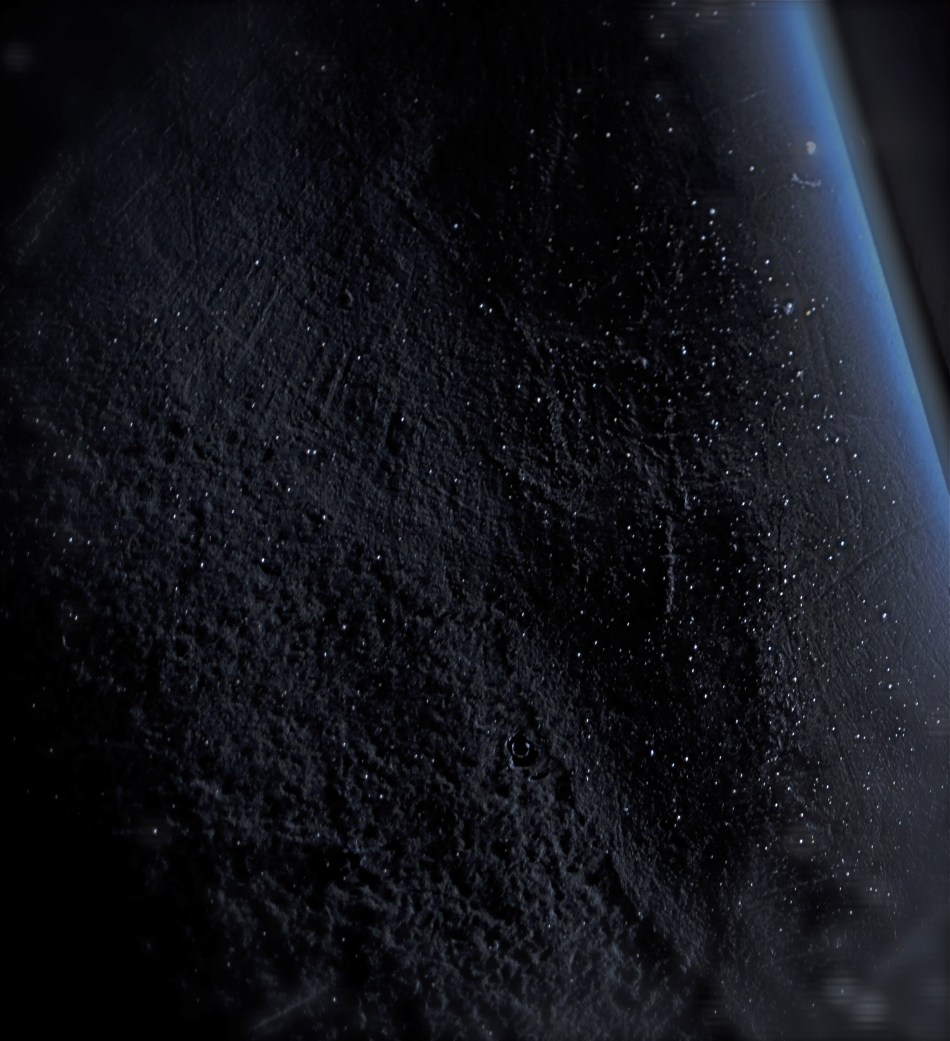

One of the site’s recent so-called “weekend projects” was to photograph anything that in any way depicted broken glass. No special terms beyond that. Cheap glass, wine glass, churchy stained glass, pick your texture, pick your context. I decided to so something with a shattered light bulb, but with a few twists. Instead of just breaking the bulb and shooting a frame, I opted to place the bulb in a food storage bag, then hammer it until it burst. Due to the sudden release of pressure when light bulbs are breached, they don’t just crack, they sort of explode, and, given the chemical treatment of the glass, there is a lot of pure white dust that accompanies the very fine glass particles. Breaking the bulb inside the bag allowed me to retain all that sediment, then make it more visible by pouring the bits out onto a black, non-reflective surface…in this case, a granite tile that I use to model product shots on.

I already liked the look of all the atomized white dust across that dull blackness, rather like a “star field”, or a cluster of debris, scattered across a vast void in space. The effect was taking shape, but the “garbage cook” inside my head was still looking for one more ingredient. The great thing about building a fantasy visual is that it doesn’t have to make “sense”….it just needs visual impact sufficient to register with the gut. If the micro-fine bits of the bulb represented some kind of space catastrophe, where was the cause? Inner stresses, like volcanoes, rupturing the Mother Bulb asunder like the planet Krypton? No, wait, what if something collided with it, some asteroid-like something that spelled doom for Planet G.E.? A quick trip out to the back yard gave me my cosmic cataclysm….I mean chunk of quartz, and the rest was just arrangement and experiment.

What does it all mean? Heck, what does beef stew mean? Making a picture can be like gradually adding random veggies and spices until something tells you it’s “soup”. And with tabletop fantasies, you get to play God with all the little worlds you’ve created.

Hey, over a lifetime, plenty of other people will take turns blowing up your work.

Why not you?

follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

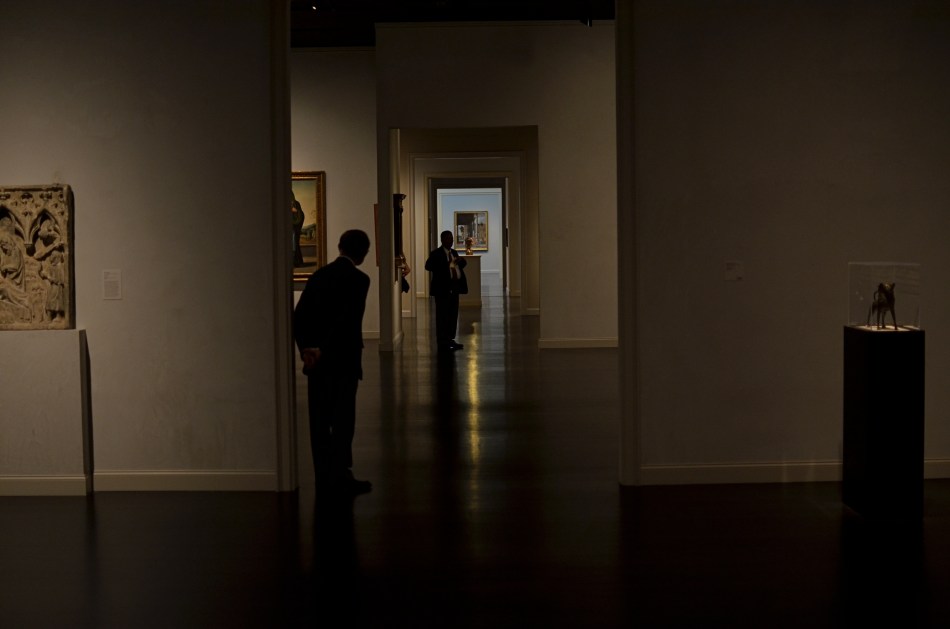

INNER SPACE, OUTER MIND

There really was a nice exhibit on display the day I took this at LACMA in Los Angeles. But this arrangement of space was arguing louder for my attention. 1/160 sec., f/1.8, ISO 320, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF YOU VISIT ENOUGH MUSEUMS IN YOUR LIFETIME, you may decide that at least half of them, seen as arranged space, are more interesting than their contents. It may be country-cousin to that time in your childhood when your parents gave you a big box with a riding toy inside it, and, after a few minutes of excitement, you began sitting in the box. The object inside was, after all, only a fire engine, but a box could be a mine shaft, a Fortress of Solitude, the dining car on the Orient Express, and so on.

And so with museums.

I truly do try to give lip service to the curated exhibits and loaned shows that cram the floors and line the walls of the various museums I visit. After all, I am, harumph and ahem, a Patron Of The Arts, especially if said museums are hosting cocktail parties and trays of giant prawns in their hallowed halls…I mean, what’s not to like? However, there are times when the endless variations on just a room, a hall, a mode of lighting, or the anticipatory feeling that something wonderful is right around the next corner is, well, a more powerful spell than the stuff they actually booked into the joint.

Spaces are landscapes. Spaces are still lifes. Spaces are color studies. Spaces are stages where people are dynamic props.

Recently spinning back through my travel images of the last few years, I was really surprised how many times I took shots inside museums that are nothing more than attempts to render the atmosphere of the museum, to capture the oxygen and light in the room, to dramatize the distances and spaces between things. It’s very slippery stuff. Great thing you find, also, is that the increased light sensitivity and white balance controls on present-day cameras allow for a really wide range of effects, allowing you to “interpret” the space in different ways, making this somewhat vaporous pursuit even more …vaporous-y.

In the end, you shoot what speaks to you, and these “art containers” sometimes are more eloquent by far than the treasures they present. That is not a dig on contemporary art (or any other kind). It means that an image is where you find it. Staying open to that simple idea provides surprise.

And delight.

follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

THE EASIEST ABSTRACTION

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU’VE HEARD THE JOKE ABOUT THE WRITER WHO TAGGED A NOTE TO A FRIEND BY SAYING, “If I’d had more time, I’d have written you a shorter letter”. That line speaks volumes about how we increase the power of communication by leaving things out. Just as great books are not so much written as re-written, so photographs often gain in eloquence when everything but the essence of the message is pared away.

You already know a tree “goes with” this reflection..but is it needed to complete the image? 1/500 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

It means being your own best editor, and, to do that, you have to be able to hate on your own work a little bit. Tough love and all that. Spare the picture and spoil the image. No sacred cows, just because they are your cows. There is no avoiding the fact that no real art comes about unless you take direct, often brutal action, to overcome the imperfections of a raw first effort. You have to intervene, again and again, in the shaping of your conception.

You can probably infer from all this that I am no fan of automodes, or of any other abdication of responsibility that lets a device, for Pete’s sake, dictate the outcome of image-making.

A few basic truths to keep before you:

Your camera is a machine with an eye attached.

You are an eye with a brain attached.

One of you is supposed to be in charge.

Guess which one.

When we merely snap a scene, freezing an arrangement of whatever we see in frame, we are only making a record. Creativity comes with abstraction, of exploring what is beyond the obvious cause-and-effect. The standard approach to showing things should actually be called the “average” approach. Look, here’s a tree, and, below, here is its shadow. Behold, here’s a scenic object next to the water, and, in the water, a reflection of that object. This simple reproduction of “reality” involves craft, to be sure, but something that falls short of art. Abstracting, adding or taking away something, and actively partnering with the viewer’s imagination take the photograph beyond a mere recording.

And that, boys and girls, is where the “art” part comes in.

Take away even a single obvious element and you change the discussion, for better or worse. Does the tree always have to be accompanied by its shadow? Does the mountain and its reflection always need to be presented as a complete “set”? It’s interesting to take even the “perfect” or “balanced” shots we cherish most and again take the scissors to part of them. Can the picture speak louder if we trim away the obvious? Can the image turn out to be something if it just stops trying to be everything?

The easiest abstractions come from changing small things, and editing can often, oddly, be an act of completion. Pictures taken in the moment are convenient, but too many images are trusted to the ease of leaning on automodes, and almost no photo is fully realized “straight out of the camera.” Believe this if you believe nothing else: nothing truly excellent ever results from putting your imagination in neutral. You have to decide whether you or the machine is the principal picture-taker.

That decision decides everything else.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye

BLUE ON THIRD AVENUE

The cyanotype option in Nikon’s monochrome posting menu makes this in-camera conversion from color easy. 1/80 sec., f/5.6, ISO 160, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

COLOR IS LIKE ANY OTHER COMPONENT IN LIGHT COLLECTION AND ARRANGEMENT, which is, really, what we are doing. Seen as a tool instead of an absolute, it’s easy to see that it’s only appropriate for some photographs. Since the explosion of color imaging for the masses seen in the coming of Kodachrome and other early consumer films in the 1930’s, the average snapper has hardly looked back. Family shots, landscapes, still life arrangements….full color or go home, right?

Well….

Oddly, professional shooters of the early 20th century were reluctant to commit to the new multi-hued media, fearing that, for some novelty-oriented photographers, the message would be the color, instead of the color aiding in the conveying of the message. Even old Ansel Adams once said of magazine editors, that, when in doubt, they “just make it red”, indicating that he thought color could become a gimmick, the same way we often regard 3-d.

In the digital age, by comparison, the color/no color decision is almost always an afterthought. There are no special chemicals, films or paper to invest in before the shutter clicks, and plenty of ways to render a color shot colorless after the fact. And now, even the post-processing steps involved in creating a monochrome image need not include an investment in Photoshop or other software. For the average shooter, monochrome post-processing is in-camera, at the touch of a button. Straight B/W and sepia and even what I call the “third avenue”, the blue duotone or cyanotype, as I’ve used above.Do such quickie options worsen the risk of gimmick-for-gimmick’s sake more than ever? As Governor Palin would say, “you betcha”. Google “over-indulgence”, or just about half of every Instagram ever taken, as evidence.

Hundreds of technical breakthroughs later, it still comes down to the original image itself. If it was conceived properly, color won’t lessen it. If it was a bad idea to start with, monochrome won’t deliver the mood or the tone changes needed to redeem it. Imagine the right image, then select the best way to deliver the message. Having quick fixes in-camera aren’t, initially, a guarantee of anything but the convenient ability to view alternatives. In the photo above, my subject was just too warm, too pretty in natural color. I thought the building itself evoked a certain starkness, a cold, sterile kind of architecture, that cyanotype could deliver far better. The shadows are also a bit more mysteriously rendered.

At bottom, the shot is just a study, since I will be using it to take far more crucial pictures of far more intriguing subjects. But the in-camera fix allows you to analyze on the fly. And, since I got into this racket to shoot pictures, and not to be a chemist, I occasionally like a fast thumbs-up, thumbs-down verdict on something I’ve decided to try in the moment.

Giving yourself the blues can be a good thing.

(follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @ mpnormaleye)

Related articles

- Toning my Cyanotype with Haritaki (altlab2011.wordpress.com)

- Beyond Color (piaffephotos.wordpress.com)

IT’S NOT EASY BEIN’ GREEN

This is the desert? A Phoenix area public park at midday. There is a way around the intense glare. 1/500 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm, straight out of the camera.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR YEARS I HAVE BEEN SHOOTING SUBJECTS IN THE URBAN AREAS OF PHOENIX, ARIZONA, trying to convey the twin truths that, yes, there are greenspaces here, and yes, it is possible for a full range of color to be captured, despite the paint-peeling, hard white light that overfills most of our days. Geez, wish I had been shooting here in the days of Kodachrome 25. Slow as that film was, the desert would have provided more than enough illumination to blow it out, given the wrong settings. Now if you folks is new around here, lemme tell you about the brilliant hues of the Valley of the Sun. Yessir, if’n you like beige, dun, brown, sepia or bone, we’ve got it in spades. Green is a little harder to come by, since the light registers it in a kind of sickly, sagebrush flavor….kind of like Crayola’s “green-yellow” (or is it “yellow-green”?) rather than a deep, verdant, top-o-the-mornin’ Galway green.

But you can do workar0unds.

In nearby Scottsdale, hardly renowned for its dazzling urban parks (as opposed to the resort properties, which are jewels), Indian School Park at Hayden and Indian School Roads is a very inviting oasis, built around a curvy, quiet little pond, dozens of mature shade trees that lean out over the water in a lazy fashion, and, on occasion, some decorator white herons. Thing is, it’s also as bright as a steel skillet by about 9am, and surrounded by two of the busiest traffic arteries in town. That means lots of cars in your line of sight for any standard framing. You can defeat that by turning 180 degrees and aiming your shots out over the middle of the pond, but then there is nothing really to look at, so you’re better off shooting along the water’s edge. Luckily, the park is below street level a bit, so if you frame slightly under the horizon line you can crop out the cars, but, with them, the upper third of the trees. Give and take.

There is still a ton of light coming down between the shade trees, however, so if you want any detail in the water or trees at all, you must shoot into shade where you can, and go for a much faster shutter speed….1/500 up to 1/1000 or faster. It’s either that or shoot the whole thing at a small f-stop like f/11 or more. In desert settings you’ve got so much light that you can truly dance near the edge of what would normally be underexposure, and all it will do is boost and deepen the colors that are there. There will still be a few hot spots on projecting roots and such where the light hits, but the beauty of digital is that you can click away and adjust as you go.

It’s not quite like creating greenspace out of nothing, but there are ways to make things plausibly seem to be a representation of real life, and, since this is an interpretive medium, there’s no right or wrong. And the darker-than-normal shadows in this kind of approach add a little warmth and mystery, so there’s that.

It was “yellow-green”, wasn’t it?

Hope that’s not on the final.

(follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye)

FIND THE OUTLIERS

Not the kind of space you’d expect to see in a visually crowded suburban environment. And that’s the point. 1/320 sec., f/8, ISO 100, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY TIME MY WIFE AND I TRAVEL, A STRANGE PHENOMENON OCCURS. We will be standing on the exact same geographic coordinates, pointing separate cameras in generally the same general area. And, invariably when she gets her first look at the pictures I took on that day, I will hear the following:

Where was THAT? I don’t remember seeing that!? Where was I?

Of course, we see differently, as do any two shooters. Some things that are blaring red fire alarms to one of us are invisible, below the radar, to the other. And of course we are both right. And valid. Admittedly, I do seem to come back with more strange, off-to-the-side-of-the road oddities than Marian does, but that may be due more to my wildly spasmodic attention span than any real or rare “vision”. Lots of it comes because I consciously trying to overcome the numbing experience of driving in a car. I have to work harder to take notice of the unconventional when repeatedly tracking back and forth,day after day, down routine driving routes. Familiarity not only breeds contempt, it also fosters artificial blindness. The “outliers” within five miles of your own house should glow like fluorescent paint….but often they seem cloaked by a kind of habit-dulled camo.

Once detected, outliers don’t quite fit within their neighboring context. The last Victorian gingerbread home in a clutch of tract houses. The old local movie theatre reborn as a Baptist church. Or, in a place like Phoenix, Arizona, where urban development is not only unbridled but seemingly random, the rare “undeveloped” lot, crammed between more familiar symbols of sprawl.

The above image is such an outlier. It’s about an acre-and-a-half of wild trees bookended by a firehouse,

a row of ranch houses, and a busy four-lane street. Everything else on the block screams “settled turf”, while this strange stretch of twisted trunks looks like it was dropped in from some fairy realm. At least that’s what it says to me.

My first instinct in cases like this is to get out and shoot, attempting, as I go, to place the outlier in its own uncluttered context. Everything else around my “find” must be rendered visually irrelevant, since it adds nothing to the image, and, in fact, can diminish what I’m after. Sometimes I also tweak my own color mix, since natural hues also may not get my idea across.

Even after all this, I often find that there is no real revelation to be had, and I must chalk the entire thing up to practice. Occasionally, I come back with something to show my wife. And I know I have struck gold if the first thing out of her mouth is, “Where is THAT?”

To paraphrase the old proverb, behind every great man is a woman who rightfully asks, “Do you know what you’re doing?”

Sometimes I have an answer….