RE-OPENING THE LAB

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS WILL ALWAYS BENEFIT FROM SOCIOLOGICAL “PIVOT POINTS“, those unique junctures in time when tectonic plates between eras shift, grind and re-configure. Images, for better or worse, are the way we testify to big changes in our world. They are documents of where one age ends and a new one begins. They illustrate contrasts between then and now.

A change in society is an opportunity for pictures, photos which become obvious, even inevitable, in telling the story of how we evolve. And one of the biggest such changes over the last decade or so has been the re-birthing of the walking neighborhood. Urban cores long given up for dead are being re-vitalized by young people who want close, hands-on engagement with city life.

Whether this shift is a boomerang effect at the end of half a century of suburban flight, an economic remedy to rising housing prices (refurbishing is cheaper than new building), an ingenious way to re-purpose old resources for a greener planet (and get rid of cars), or just a generational restlessness, the old laboratory known as the urban neighborhood is back open for business, with darkened and deserted blocks sprouting new colors, shops, rhythms. Prime picking for photographers, who, first and foremost, go where the stories are.

For me, lateral, wide-angle portraits of businesses is great fun, as I try to channel the “neighborhood in miniature” panels made popular by painter Norman Rockwell during his magazine years. Watching foot traffic flow between laundries and liquor stores, with maybe a pizza joint in between, affords an instant variety of color, signage, reflections, and texture…in other words, lots to work with.

The street is dead. Long live the street.

FACES WITHOUT FEATURES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SOME OF MY URBAN PHOTOGRAPHY COULD POTENTIALLY STRIKE THE AVERAGE VIEWER as somewhat remote, even a bit cold. It flies in the face of some of the universally held “truths” about so-called street photography. Sometimes it doesn’t even have a face. Or faces.

If the best street shooters are thought to reveal truth in the features of the denizens of all those boulevards, then I might really be at a disadvantage, since many of my images are not about faces.

They are, however, about people.

I tend to use passersby, in city pictures, to several ends. beyond the regular kind of unposed portraiture that is standard “street” orthodoxy. One is scale, that is, how they dominate or are diminished by the sheer size or scope of their surroundings. Some cities seem to swallow people, reducing them to anti-sized props in an architect’s tabletop diorama. I try to show that effect, since, as a city dweller, it affects me visually. Other times, I show people completely silhouetted or swaddled in shadow. This is not because their faces aren’t important, but because I’m trying to accurately show their roles as components in an overall choreography of light, as I would a mailbox or a car. Again, the idea is not to avoid or conceal the stories that may reside in their faces, but to also accentuate their body language, how they occupy a space, and, yes, as abstract design elements in a large still life (okay, that sounds a bit clinical).

I certainly bow to the masters whose controlled ambushes of strangers have captured, in candid facial shots, harrowing, inspiring, or amusing emotions that deepen our understanding of each other. You could rattle off their names as easily as I. But using people in pictures isn’t only a miniature invasion into their features, and certainly isn’t the only way to depict their intentions or dreams.

And then there is the other problem for the street portraitist, in that some faces will remain ciphers, resisting the photographer’s probe, explaining or revealing nothing. In those cases, a face poses more questions than it answers. As usual, the argument is made by the individual picture.

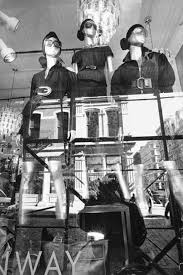

TWO-WAY GLASS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF THE EYES ARE THE WINDOW TO THE SOUL, then certain windows are an eye into contrasting worlds.

Photographers have devised a wide number of approaches when it comes to using windows as visual elements. Many choose to shoot through them with a minimum of glare, as if the glass were not there at all. Others use them as a kind of surreal jigsaw puzzle of reflected info-fragments.

To show these two approaches through the eyes of two great photographers, examine first Eugene Atget’s shots of 19th-century Paris storefronts, which mostly concentrated on shopkeeper’s wares and how they were arranged in display windows. Straightforward, simple. Then contrast Lee Friedlander’s 21st-century layered blendings of forward view and backward reflection (seen at left), which suspends the eye between two worlds, leaving the importance of all that mixed data to the viewer’s interpretation.

Much of my own window work falls into the latter category, as I enjoy seeing what’s inside, what’s outside, and what’s over my shoulder, all in the same shot. What’s happening behind the glass can be a bit voyeuristic, almost forbidden, as if we are not fully entitled to enter the reality on the other side of the window. But it’s interesting as well to use the glass surface as a mirror that places the shop in a full neighborhood context, that reminds you that life is flowing past that window, that the area is a living thing.

Thus, in an urban setting, every window is potentially two-way glass. Now, just because this technique serves some people as a narrative or commentary doesn’t make it a commandment. You have to use the language that speaks for you and to your viewer. Whatever kind of engagement serves that relationship best dictates how you should be shooting. I just personally find layered windows a fun sandbox to play in, as it takes the static quality away from a still photo to some degree, as if the image were imbued with at least the illusion of motion.

Sometimes it’s good to conceal more than reveal, and vice versa. The only “must”, for this or any other technique in photography, is to be totally mindful as you’re creating. Choose what you mean to do, and do it with your eyes fully open.

OF DISTANCES AND DOMAINS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY IS AN EFFECTIVE WAY TO MEASURE MAN’S RELATIONSHIP to his physical environment, giving us the distance we need to see these arrangements from a more objective distance. People design places in which other people are to live and work, but once these plans get off the drawing board, it can become unclear what people’s place in the whole puzzle was intended to be.

More to the point, there is real picture-making potential in the occasional mis-match between what we design and how we fit into it. Some things that seem terrific to the people on the planning board seem cold or intimidating to regular users once they’re actually built. Seeing us try to find our place in things that are really inhospitable can be visually interesting because it makes us look and feel somewhat alien. We can become oddly placed props in our own projects, as the places made to house our dreams look more like warehouses for our nightmares.

Of course, one man’s horror is another man’s heaven, a rule that has certainly been constant over the history of innovation. That means, artistically, that we can wind up, inevitably, making images that start arguments, which is, I believe, the perfect function for art anyway. It’s one thing to smear a daub of paint on a canvas and lacerate someone’s vision with it. After all, you can abandon the painting, leave the gallery, etc. But if the building that was meant to be the gallery seems like a bad fit for you as a human being, that’s something else entirely.

The right compositions with the right lenses deliver stark visual messages about how we slot ourselves into the world we’ve created. Sometimes we make a statement for the ages. Sometimes we erect mouse mazes. Either way, there’s a picture in the process.

STREET PHOTOGRAPHY (LITERALLY)

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NEIGHBORHOODS HAVE THEIR OWN VISUAL SIGNATURES, and photographers looking to tap into the energy of streets do well to give their locales a bit of advance study, the better to try to read an area’s particular identity. Sometimes the storytelling potential lies in a single building, even a part of a building. Other times it’s the mix of foot traffic. And, every once in a while, the saga of a street lies in the pavement itself.

New York City’s South Street Seaport district is drenched in local lore, tracing the contours of its alleys and warehouses to the beginnings of Manhattan’s first days as an international shipping destination. From the times of the Dutch’s tall-masted sailing vessels to the present mix of museum and modern retail, the port, on a typical day, offers color, texture, and a feeling of deeply rooted history that is a goldmine for photographers.

Of course, every neighborhood has its off days, and, on my recent trek to the area, a persistent, wind-driven rain had chased all but the hardiest locals off the streets and into the oaky timbers of the port’s quaint shops. Life on the street slowed to a crawl as iron-grey skies robbed the scene of its bolder hues. It was a day to huddle indoors with a good read and a hot cuppa anything. My camera, usually an unfelt burden around my beltline, began to drag like an anchor, stuffed into my woolen jacket to ward off the pelting drizzle, giving me the appearance of someone in sore need of a hip replacement.

Despairing of finding any vital activity along the street, I turned in desperation to the pavement itself, realizing that, in this eastward edge of Manhattan, the texture of the roads abandons the even concrete of most of the island and reverts to the cobbled brick textures of Melville’s time, with many old waterfront fixtures installed at curbside for extra atmosphere. Suddenly I had a little story to tell. The varied mix of firings in the brick, along with the steady rain, delivered the vivid color that was lacking in the area’s shops, allowing me to create an entire frame from just the street itself. Finding that some scale was needed, I sought out an old iron fixture for the left edge of the photo with just the legs and feet of two passing girls to balance out the right side. Suddenly there was enough, just enough of something to make a picture.

Obviously, if the street had been mere wet concrete or blacktop, the impact would have been different, and, were I in a different neighborhood, the street itself might have been unable to compete with the businesses for color or interest. On that morning, however, simple worked best, and my camera, at least for a moment, felt less like an anchor and more like a sailing ship.

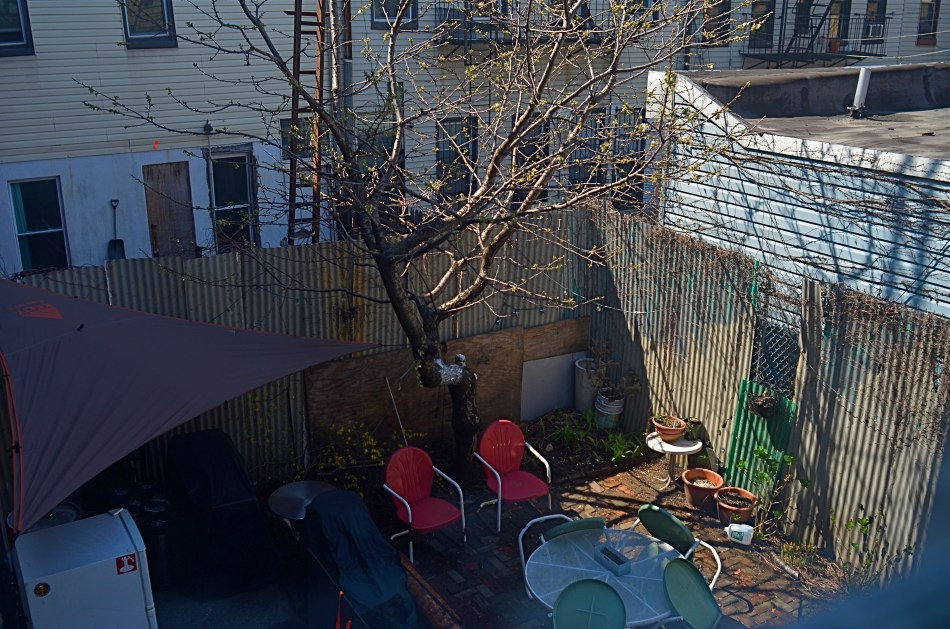

MY LITTLE SLICE OF HEAVEN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

URBAN ENVIRONMENTS ARE MEAT GRINDERS, greedily chomping maws that mulch and mash humans into manageable shapes and sizes, compacting lives into spaces too small for the average burrowing rabbit and crushing a few millions dreams in the process. And the endless flow of stories that result from this struggle, for photographers, show Man trying to steer clear of the maw, or at least salvage a few limbs as he does battle with it.

Life in cities is about small words with big import. Safety. Shelter. Privacy. Relief. Escape. Dreams. Prayers.

Territory.

Photographic sagas in cities begin and end with the demarcation of personal boundaries. Over here, this is mine. Over there, yours. This is how I identify the mineness. With decorations. With ritual. With color, context, property. I live in the city, but I say on what terms. Cross this line and the city ends. And I begin.

The story of how people in cities define their personal space is a tremendous drama, and, often, a fabulous comedy as well. In the above photo, taken across the endless track of backyard spaces in a Brooklyn neighborhood, space is, obviously, at a premium. But it’s how I fill it that defines me. The little crush of chairs and tables is not so much a patio as it is a healthy exercise in self-delusion.

My little slice of heaven.

Next year, I might get a barbecue.

When the Drifters sang of cities in Carole King’s amazing song, “Up On The Roof”, every city dweller already knew the words. I leave all that rat-race noise down in the street. And every person who walks cities with a camera knows how to identify, and bear witness to, all those little rooves. Or patios. Or pink porchlights.

People need their space, and photographers will always be on hand to show exactly what they came up with.

Just picture it.

I’M LOOKING THROUGH YOU

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ANYONE WHO REGULARLY PHOTOGRAPHS GLASS SURFACES realizes that the process is a kind of shot-to-shot negotiation, depending on how you want the material to react and shape your subject. There is really no absolute “look” for glass, as it has the ability to both aid and block the view of anything it’s around, in front of, or near. Viewed in different conditions and angles, it can speed the impact of an image, or foil it outright.

I love shooting in urban environments, where the use of glass has shifted dramatically in recent decades. Buildings that were 90% brick or masonry just fifty years ago might be predominantly wrapped in glass today, demonstrably tilting the ratios of available light and also changing what I call the “see-through” factor…the amount of atmosphere outside a building can be observed from inside it. This presents opportunities galore of not only what can be shown but also how abstracted glass’ treatment of reflection can serve a composition.

Against the advice of many an online pundit, I keep circular polarizing filters permanently attached to the front of all my lenses so that I can modify reflections and enhance color richness at my whim. These same pundits claim that leaving the filter attached when it’s not “needed” will cost you up to two stops of light and degrade the overall image quality. I reject both these arguments based on my own experience. The filters only produce a true polarizing effect if they are either at the right viewing angle vis-a-vis the overhead sun, or if they are rotated to maximize the filtering effect. If they don’t meet either of these conditions, the filters produce no change whatever.

Even assuming that the filter might be costing you some light, if you’ve been shooting completely on manual for any amount of time, you can quickly compute any adjustments you’ll need without seriously cramping your style. Get yourself a nice fast lens capable of opening to f/1.8 or wider and you can even avoid jacking up your ISO and taking on more image noise. Buy prime lenses (only one focal length), like a 35mm, and you’ll also get better sharpness than a variable focal length lens like an 18-55mm, which are optically more complex and thus generally less crisp.

In the above image, which is a view through a glass vestibule in lower Manhattan, I wanted to incorporate the reflections of buildings behind me, see from side-to-side in the lobby to highlight selected internal features, and see details of the structures across the street from the front of the box, with all color values registering at just about the same degree of strength. A polarizer does this like nothing else. You just rotate the filter until the blend of tones works.

Some pictures are “about” the subject matter, while others are “about” what light does to that subject, according to the photographer’s vision. Polarizers are cheap and effective ways to tell your camera how much light to allow on a particular surface, giving you final say over what version of “reality” you prefer. And that’s where the fun begins.

UNKNOWN KNOWNS

Everyone is visible, yet no one is known. Faceless crowds serve as shapes and props in a composition.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WE OFTEN WRITE IN THESE PAGES ABOUT PHOTOGRAPHY’S UNIQUE ABILITY to either reveal or conceal, and how we toggle between these two approaches, given the task at hand. Photographic images were originally recorded by using science to harness light, to increase its ability to illuminate life’s enveloping darkness, just as Edison did with the incandescent bulb. And in their attempt to master a completely new artistic medium, early photographers were constantly pushing that dark/light barrier, devising faster films and flash technology to show detail in the darkest, dimmest corners of life.

And when that battle was won, an amazing thing happened.

Photographers realized that completely escaping the dark also meant running away from mystery, from the subtlety of suggestion, from the unanswered questions residing within their pictures’ shadows. And from the earliest days of the 20th century, they began to selectively take away visual information, just as painters always had, teasing the imagination with what could not be seen.

City scenes which feature individual faces in crowds opt for the drama (or boredom) written in the face of the everyday man. Their scowls at the noonday rush. Their worry at the train station. Their motives. But for an urban photographer, sometimes using shadow to swallow up facial details means being free to arrange people as objects, revealing no more about their inner dreams and drives than any other prop in an overall composition. This can be fun to play with, as some of the most unknowable people can reside in images taken in bright, public spaces. We see them, but we can’t know them.

Experimenting with the show it/hide it balance between people and their surroundings takes our photography beyond mere documentation, which is the first part of the journey from taking pictures to making them. Once we move from simple recording into interpretation, all the chains are off, and our images can really begin to breathe.

INVISIBLE CITIES

New York is one of the great treasure troves for lovers of Art Deco. This complex, along Lexington Avenue, is literally in the shadow of the Chrysler building.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS, IN THE WORLD OF SPORTS, A PSYCHOLOGICAL EDGE known as the “home field advantage”, wherein a team can turn a superior knowledge of its native turf against its visiting opponent. The accuracy of this belief has never been conclusively proven, but it’s interesting to think on whether it applies to photography as well. Do we, for the purposes of making pictures, know our own local bailiwicks better than visitors ever can? Or is it, as I suspect, the dead opposite?

Familiarity may not breed contempt, but, when it comes to our seeing everything in our native surroundings with an artistic eye, it can breed a kind of invisibility, a failing to see something that has long since receded into the back part of our attention, and thus stops registering as something to see anew, or with fresh interpretation. How many buildings on the street we take into the office are still standouts in our mind’s eye? How many objects would we be amazed to learn are actually part of our walk home, and yet “unseen” by us as we mentally drift along that drab journey?

It may be that there is actually a decided “out-of-towner” advantage in visiting a place where you have no pre-conceptions or habitual routes, in approaching things and places in cities as totally new, free of prior associations. I’ve often been asked of an image, “where did you take that?” only to inform the questioner that the building in the picture is a half block from their place of business. The above image was taken on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan, not more than a half block and across the street from the Chrysler building. It is a gorgeous treasure of design cues every bit as symbolic of the golden age of Art Deco as its aluminum clad neighbor, and yet I could hold a contest amongst many New Yorkers as to where or what it is and never have to award the prize money. The Chrysler’s very fame eclipses its neighbors, rendering them less visible.

Perception is at the heart of every visual art, and the most difficult things to re-imagine are the ones which have ceased to strike us as special. And since everyone lives in a city that is at least partly invisible to them, it stands to reason that an outside eye can make its own “something new” out of everyone else’s “something old”. Realize and celebrate your special power as a photographic outlier.

THE WHEN OF WHIMSY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

For decades, the legendary Life magazine provided richly illustrated summaries of the week’s events, competing with other photo-laden national weeklies from Look to Fortune, Collier’s to Liberty for the eyeballs of generations of subscribers. The weekly giants perfected the photo-essay, laying out stories on elections, wars, fashions and the arts in serial narrative form from opening headline to closing paragraph. Life has even had a second “life” of sorts, ceasing weekly publication clear back in 1972, but still visible on newsstands to the present day in re-mixed, themed reissues of its iconic image archives.

One of my favorite features in Life over the years was the Miscellany page, tucked just inside the magazine’s back cover, and reserved almost exclusively for whimsy or fun. Freed from the journalistic constraints of the rest of Life, the Miscellany images ended the week on an up note with novelty and warmth providing relief from starker, sterner material. Nearly all of the photos were “human interest” in nature, featuring amusing interactions between people. Lovers. Kids. Day laborers. There was a true “caught in the act” flavor to the shots, and most looked like lucky candids rather than staged or manipulated images.

The feature informed my own brand of street photography, the snap that makes the mind speculate on the story that takes place both before and after the click. Sometimes people figure in my own moments of whimsy. Other times, as in the case of the image up top, an unusual arrangement of elements captures my imagination, making me wonder how these particular things got to this particular place. The idea of a single blooming flowerpot on a cart standing outside a very industrial loading dock caught my eye, as the two things don’t seem, at first glance, to belong to the same world. I almost spent too long thinking about it, too, since, several seconds after I snapped the picture, a worker came into frame and removed the vase, vaporizing my little tableau forever. Snooze you lose.

Miscellany appealed to my child’s sense of how to tell a story in pictures, not by what was shown but by what else is going on. There is a limited “when” for all whimsy, and, as the editors of Life realized so well, a time when one picture on the page is worth a thousand more in the mind.

DEM DARN DONT’S

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE GLIB REMARK THAT YOU HAVE TO LEARN ALL THE RULES IN LIFE BEFORE YOU CAN BREAK THEM is maddeningly true, at least for me. Early on in my foto-fiddling, I was eager to commit all the world’s accumulated photographic do’s and don’ts to memory, like a biblical scholar nailing scripture passages, and shooting as if to enshrine those stone-written truths in art. I used words like always and never to describe how to make pictures in a given situation. I kept the faith.

And then, when I suddenly didn’t, my stuff stopped being pictures and started being photographs. Absolutes of technique are good starting places but they usually aren’t the best places to stick and stay for life. And at this point in my personal trek (seventh-inning stretch), I feel the shadow of all those do’s and don’ts swirling about like little guardian angels, but I worry first and foremost about what makes a given image work.

You no doubt have many pictures you’ve made which you simply like, despite the fact that they flaut, or even fracture, the rules. The above image, shot earlier this week at a multi-floor urban marketplace/eatery, struck me for two reasons. First, because of how many basic rules of “proper” composition it clearly violates; and secondly, just how much I don’t care, because I like what it does. To illustrate my point, I’ve provided citations from an article titled Principles Of Composition to cite specific ways that the photo is, well, wrong.

Have A Strong point of interest. Well, there isn’t any particular one, is there? Lots of conflicting stuff going on, but that’s the natural rhythm of this place. It’s a beehive. One man’s clutter is another man’s full “pulse of life”, and all that.

Don’t place the horizon line, or any strong vertical or horizontal lines, right in the middle of a picture. And make sure the lines aren’t tilted. Okay, well, since there is a distinct difference between the “level-ness” of the crossbeams over the lower floor and the slanted lines of the skylight above, there really isn’t a way to make the entire picture adhere to the same horizontal plane. However, the off-kilter sagginess of the old building actually lends it a little charm , unless I’m just drunk.

Keep compositions simple, avoiding busy backgrounds that distract from your subject. Granted, there are about five different sub-pictures I could have made into separate framings within this larger one, but that would defeat the object of overall bustle and sprawl that I experienced looking out over the entire scene. Sure, some compositions get so busy that they look like a page out of Where’s Waldo?, but certain chaotic scenes, from Grand Central Terminal to Picadilly, actually reward longer, deeper viewing.

Place a subject slightly off-center rather than in the middle of a photo. Yeah, well, that’s where that “strong point of interest” rule might have helped. Sorry.

Do these deviations mean the image was wrong, or wrong for certain circumstances? Every viewer has to call that one as he sees it. Me, I am glad I decided to shoot this scene largely as I found it. It needed to work with natural light, it needed to be shot wide and deep, and it needed to show a lot of dispirate activity. Done done and done. I heard all the rules in my head and chose the road not taken.

Or taken. I forget which.

A NEW PATH

A dream of life comes to me. Come on up for the rising tonight—-Bruce Springsteen

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE POST 9/11 RESURRECTION OF LOWER MANHATTAN might have begun as a kind of act of defiance, a refusal to knuckle under to fear in the aftermath of the largest attack in history on American soil. Somewhere amidst the tears and rage, however, the project to re-establish this crucial corner of New York City moved onto a higher plane, transitioning from anger to elegance, mourning to…morning. And now, for both casual travelers and astounded visitors, the master plan for the area is an ever-blooming monument to faith. To excellence.

Photographers from around the world have known, from the days of the first cleanups, that an amazing opportunity for historic documentation was unfolding on this hallowed ground, and their images have provided an invaluable service in tracking the city’s transition between two distinct eras. The first two mile-markers in this transformation, the openings of World Trade Center One and the 9/11 Memorial Museum, have been interpreted in a global cascade of visual impressions, occurring, as they have, in the first explosion of social media and digital imaging. And now, the third piece of the puzzle, the stunning new Oculus PATH terminal, is nearly ready to serve as the proof that the city, along with all its millions of comings and goings, is still very much open for business.

Oculus Aloft: the steel wings of the new PATH terminal for New York’s World Trade Center, nearing completion in 2015.

Photographers have already made a visit to Oculus something of a pilgrimage, and, looking over the first few photos to emerge from their visits, it might be closer, architecturally, to a religious experience. Designed by Santiago Calatrava, the structure, presenting its ribbed wings to the skies like an abstract bird of prey, resembles, within, a kind of sci-fi cathedral of kaleidoscopic light effects, serving as both monument and utility. An inventory of its features and a gallery of interior images can be seen here.

And, of course, this is New York, so opinion on the Oculus’ value, from poetic prayers to crass carping, will go through the usual grappling match. But, whatever one’s eventual take on the project, its power as a statement….of survival, of power, of hope, and, yes, of defiance, cannot be denied. To date, I’ve only been able to photograph limited parts of the construction phase (see above), but I will be back after the baby’s born. And my dreams will collide with Oculus’ own, and something magical will happen inside a box.

Make your way to Manhattan, and let your own camera weigh in on the new arrival.

Come On Up For The Rising.

FACE TIME

The resurrected World Trade Center, as seen at eye (rather than “craning neck”) level. 1/125 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 24mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I AM OFTEN ASKED WHY ARCHITECTURE FIGURES SO STRONGLY in my photography, and I can only really put part of my answer into words. That’s what the pictures are for. I imagine that the question itself is an expression of a kind of disappointment that my work doesn’t focus as much on faces, as if the best kind of pictures are “people pictures”, with every other imaging category trailing far behind. But I reject that notion, and contend that, in studying buildings, I am also studying the people who make them.

Buildings can be read just as easily as a smile or a frown. Some of them are grimaces. Some of them are grins. Some of them show weary resignation, despair, joy. Architecture is, after all, the work of the human hand and heart, a creative interpretation of space. To make a statement? To answer a need? The furrowed brows of older towers gives way to the sunny snicker of newborn skyscrapers. And all of it is readable.

In photography, we are revealing a story, a viewpoint, or an origin in everything we point at. Some buildings, as in the case of the first newly rebuilt World Trade Center (seen above), are so famous that it’s a struggle to see any new stories in them, as the most familiar narratives blot the others out of view. Others spend their entire lives in obscurity, so any image of them is a surprise. And always, there are the background issues. Who made it? What was meant for it, or by it? What world gave birth to this idea, these designs, those aims?

Photography is about both revelation and concealment. Buildings, as one of the only things we leave behind to mark our having passed this way, are testaments. Read their faces. No less than a birthday snapshot, theirs is a human interest story.

INTERACTIONS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S FAIRLY EASY TO FIGURE OUT WHERE TO TAKE YOUR CAMERA if you are trying to visually depict a vibe of peace and quiet. Landscapes often project their serenity onto images with little translation loss, and you can extract that feeling from just about any mountain or pond. For the street photographer, however, mining the most in terms of human stories is more particularly about locations, and not all of them are created equal.

Street work provides the most fodder for storytelling images in places where dramatically concentrated interactions occur between people. One hundred years ago, it might have been the risk and ravage of Ellis Island. On any given sports Sunday, the opposing dreams that surround the local team’s home stadium might provide a rich locale. But whatever the site, social contention, or at least the possibility of it, generates a special energy that feeds the camera.

In New York City, the stretch of Fifth Avenue that faces the eastern side of the Empire State Building is one such rich petri dish, as the street-savvy natives and the greener-than-grass tourists collide in endless negotiation. Joe Visitor needs a postcard, a tee-shirt, a coffee mug, or a discounted pass to the ESB observation deck, and Joe Hometown is there to move the goods. Terms are hashed over. Information slithers in and out a dozen languages, commingling with the verbal jazz of Manhattan-speak. Deals are both struck and walked away from. And as a result, stories flow quickly past nearly every part of the street in regular tidal surges. You just pick a spot and the pictures literally come to you.

In these images, two very different tales unfold in nearly an identical part of the block. In the first, bike rickshaw drivers negotiate a tourist fare. How long, how far, how much? In the second, two regulars demonstrate that, in New York, there is always the waiting. For the light. For parking. For someone to clear away, clear out or show up. But always, the waiting. These are both little stories, but the street they occur on is a stage that is set, struck and re-set constantly as the day unfolds. A hundred one-act plays a day circle around those who want and those who can provide.

Manhattan is always a place of great comings and goings, and here, in front of the most iconic skyscraper on earth, those who haven’t seen anything do business with those who’ve seen it all. Street photography is about opportunity and location. Some days give you one or the other. Here, in the city that never sleeps, both are as plentiful as taxicabs.

CHOCK-A-BLOCK

Yes, you could find a more frustrating job than making city maps for Boston streets. But you’d have to look hard….

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN WE THINK OF URBAN BLOCKS, IT’S NATURAL TO THINK of those blocks as regular rectangles, well-regulated, even streets that run at direct parallels or hard right angles to each other. And while there certainly are cities with such mathematically uniform grids, some of the most interesting cities in the world don’t conform to this dreamy ideal in any way. And that means opportunities for photographers.

We’ve all seen street scenes in which the left and right sides of the road vanish directly toward the horizons, like staring down the middle of a railroad bed. But for the sake of dramatic urban images, it’s more fun to seek out the twisty mutants of city design; the s-and-z curves, the sudden zigzags, the trapezoids and triangles which signify confusion to cabbies and pedestrians but which mean good times for photogs. Let’s face it; snapping pictures of orderly things gets old fast. The very nature that makes us idealize “rightness” also makes us want to photograph “wrongness.”

That’s why I love to shoot in towns where the city was laid out with all the logic of the Mad Hatter on speed, those streets that seem barely coherent enough to admit the successful conduct of trade. Cities where locals and visitors alike curse the names of the urban planners, if there ever had been planners, if there ever had been a plan. A grand collision of avenues and alleys that looks like a kid whose teeth are crowding together in a greedy orthodontist’s dream fantasy. In such cities, including Manhattan, Pittsburgh, San Francisco, Boston and many others, “order” is a relative term. There are precious few neat streets vanishing back to infinity, politely lined by cooperative structures queueing up parallel to the curb. And that’s my kind of living, breathing… chaos.

As a mild example, consider the Boston street shown above, on which nearly every building seems slightly askew from every other building, sitting on foundations that jut out at every conceivable angle and plane. It’s a grand, glorious mess, and a much more interesting way to show the contrasting styles that have sprouted in the neighborhood over the centuries. It’s reality that looks like an optical illusion, and I can’t get enough of it.

A straight line may be the shortest distance between two points, but it’s also the least interesting. Go find cities that make no sense, God bless ’em.

MODEL CITIZENS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE ROLE OF THE URBAN PHOTOGRAPHER IS TO REKINDLE OUR RELATIONSHIP to our cities, to ignite a romance that might have gone cold or fizzled out. We grow up inside the buildings and streets of our respective towns one day at a time, and, while familiarity doesn’t always breed contempt, the slow, steady drip of repetitive sequence can engender a kind of numb blindness, in that we see less and less of the places we inhabit. Their streets and sights become merely up, down, in, out, north side or east side, and their beauty and detail dissolve away before the regular hum of our lives.

An outside eye, usually trained on a camera, is a jolt of recognition, as if our city changed from a comfy bathrobe into a cocktail dress. We even greet images of our cities with cries of “where’s THAT????”, as if we never saw these things before. The selective view of our streets through a camera, controlling framing, context, color and focus, enchants us anew. If the photog does his job properly, the magic is real: we truly are in new territory, right in our own backyards.

A city with iconic landmarks, those visual logos that act as absolute identifiers of location, actually are easier for the urban photographer, since their super-fame means that many other remarkable places have gone under-documented. Neighborhoods are always rising and falling, as the Little Italys fade and the Chinatowns ascend. Yesterday’s neglected ghetto becomes today’s hip gallery destination. Photographers can truly rock us out of the lethargy of daily routine and reveal the metropolis’s forgotten children in not only aesthetic but journalistic ways, reminding us of problems that need remedy, lives that plead for rescue.

The photographer in the city is an interpretive artist. His mantra: hey, townies, you ain’t seen nothin’ yet.

WITHOUT A LEG TO STAND ON

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SHOOTING ON A TRIPOD IS OFTEN RECOMMENDED as the way to afford yourself the most stability in a long exposure. After all, few of us are robotic enough to hold a camera stock-still for anything below a third of a second, so it’s a no-brainer to park your camera on something that’s too inhuman to flinch. You can also take amazing stuff hand-held on shorter night exposures, so long as you (a) have a lens that will shoot around f/1.8 or wider and (b) you can live with the noise a higher ISO will engender.

So, yeah, tripods have their place, but they are not the only determinants in the success of a night-time shoot. And those other x-factors can severely compromise your results. There is the stability of the tripod itself, which isn’t a big sweat if you shelled out $900 for a carbon-fiber Gitzo Pan/Tilt GK, but might generate heartburn if you got something closer to a set of metallic popsicle sticks for $29 at Office Max. The shot above was taken using my own modest (cheap) rig atop Mount Washington across from downtown Pittsburgh, and a few of the healthier gusts threatened to take it and me on a quick lap around the riverfront. Some people buy sandbags. Some believe in the power of prayer. Your choice.

Another x-factor for ‘pod shots is the actual weather you’re shooting in, which will, let’s say, shape your enthusiasm for staying out long enough to get the perfect shot. The smaller your aperture, the longer the exposure. The more long exposures you take, the longer you, yourself, are “exposed”…to snow, sleet, and all that other stuff that mailmen laugh at. Again, referencing the above image, I was contending with freezing drizzle and a windbreaker that was way too thin for heroics. Did I cut my session short? i confess that I did.

I could also mention the nagging catcalls of the other people in my party, who wanted me to, in their profound words, “just take the damned picture” so they could partake of (a)a warm bar, (b) a cold beer, (c) a hot waitress. Result: a less than perfect capture of a fairly good skyline. A little over-exposed, washing out the color. A little mushy, since the selfsame over-exposure allowed the building lights to burn in, rendering them glow-y instead of pin sharp. I was able to fix some of the color deficiencies later, but this is not a “greatest hits” image by any stretch.

Tripods can be lifesavers, but you must learn to maximize their effectiveness just like any other piece of camera equipment. If you’re going to go to a buncha trouble to get a shot, the final result should reflect all that effort, quality-wise.

YESTERGRUBBING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I ALWAYS SCRATCH MY HEAD WHEN I SEE AN EATERY sporting a sign that boasts “American Cuisine”, and often have to suppress an urge to step inside such joints to ask the proprietor to explain just what that is. If there is one thing about this sprawling broad nation that can’t be conveniently corralled and branded, it’s the act of eating. Riff through a short stack of Instagrams to see the immense variety of foodstuffs that make people say yum. And as for the places where we decide to stoke up….what they look like, how they serve us, how they feel….well, that’s a never-ending task, and joy, for the everyday photographer.

Eating is, of course, more than mere nourishment for the gut; it’s also a repast for the spirit, and, as such, it’s an ongoing human drama, constantly being shuffled and re-shuffled as we mix, mingle, disperse, adjourn and regroup in everything from white linen temples of taste to gutbucket cafes occupying speck of turf on endless highways. It’s odd that there’s been such an explosion of late in the photographing of food per se, when it’s the places where it’s plated up that hold the real stories. It’s all American, and it’s always a new story.

I particularly love to chronicle the diners and dives that are on the verge of winking out of existence, since they possess a very personalized history, especially when compared with the super-chains and cookie-cutter quick stops. I look for restaurants with “specialities of the house”, with furniture that’s so old that nobody on staff can remember when it wasn’t there. Click. I yearn for signage that calls from the dark vault of collective memory. Bring on the Dad’s Root Beer. Click. I relish places where the dominant light comes through grimy windows that give directly out onto the street. Click. I want to see what you can find to eat at the “last chance for food, next 25 mi.” Click. I listen for stories from ladies who still scratch your order down with a stubby pencil and a makeshift pad. Click. Click. Click.

In America, it’s never just “something to eat”. It’s “something to eat” along with all the non-food side dishes mixed in. And, sure, you might find a whiff of such visual adventure in Denny’s #4,658. Hey, it can happen. But some places serve up a smorgasbord of sensory information piping hot and ready to jump into your camera, and that’s the kind of gourmet trip I seek.

TESTIMONY

by MICHAEL PERKINS

I SEE MANY, MANY HOMELESS PEOPLE THESE DAYS. Sometimes on

the streets of my home city. More occasionally on the streets of other towns. And every single day, without fail, on every photo upload site in the world. Many of the uploaders think this is “street photography”.

Many of the uploaders need to think again. Hard.

The mere freezing in a frame of someone whose lousy luck or bad choices have placed him on the street is not, of and by itself, some kind of visual eloquence. Not that it can’t be, if some kind of story, or context, or statement accompanies the image of a person driven to desperation. But not the careless and heedless snaps that are, I will say, stolen, at people’s expense, every day, then touted as art of some kind. The difference, as always, is in the eye of the photographer.

Many millions of people have been “captured” in photographs with no more revelatory power than a fire hydrant or a tree, and just catching a person unawares with your camera is no guarantee that we will understand him, learn what landed him here, care about his outcome. That’s on you as a photographer.

If all you did was wait until someone was fittingly juxaposed with a row of garbage cans, a grimy brick wall, or an abandoned slum, then lazily clicked, you have contributed nothing to the discussion. Your life, your empathy, your sense of loss or justice….all must interact with your shutter finger, or you have merely committed an act of exploitation. Oh, look at the poor man. Aren’t I a discerning and sensitive artist for alerting humanity to this dire issue?

Well, maybe. But maybe not. Photographs are conversations. If you don’t hold up your end of it, don’t expect the world to pick up the slack. If you care, then make sure we care. After all, you’ve appropriated a human being’s image for your own glory. Make sure he gave that up for something.

INVITATION TO THE DANCE

Seattle Street Stomp, Sunday Night (2016)

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY REACTS TO SHIFTS IN HUMAN BEHAVIOR, in that it both reports and creates the news. Let people surge or sparkle in any particular direction, and the camera will shift with them, for good or ill. Photographers are camp-followers by nature, and instinctively sniff out the Next Big Thing, the Next Medium Thing, even the next Is This A Thing? in search of subject matter.

There is, at this writing, a wealth of story-telling to be done in the rebirth of American urban centers, and it’s more than just stopping by the hottest new part of town. Suddenly, it’s about the complete reversal of the systemic desertion of cities that began right after World War II, with a new generation sizing up thousands of Spielbergian burbs and finding them wanting. Moreover, urban cores are being not just renovated but embraced, not merely as this year’s megatrend but as this age’s new answer. In city after city, we are coming home, transforming our idea of “a life” to define walkable neighborhoods, an explosion in the arts, dense diversity, and locally owned businesses. It’s a great time for cities, and a great time to be a photographer.

All of human activity, from ritual to celebration, social interaction to creativity, is being re-cast in urban terms, with block after block being claimed in the name of re-use and re-purpose. It’s greener, it’s groovier, and it is rich with visuals, as the barn dance becomes the street stomp and the dead warehouse becomes the very alive coffee-house. Most importantly, children are being born into places where they can walk to real shops versus driving to unreal chains. Something is up, and it’s not merely generational, and the camera has a role in all of this.

A role and a say.

Share this:

September 25, 2016 | Categories: Americana, Cities, Commentary, Neighborhoods | Tags: City Life, Street Photography, Urban Trends | Leave a comment