HAPPY-EN-STANCE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S FAIR TO SAY that photographers are occasionally the worst possible judges of what will save or spoil a picture. Try as we may to judiciously assemble the perfect composition, there are random forces afoot in the cosmos that make our vaunted “concepts” look like nothing more than lucky guesses. And that’s just the images that actually worked out.

All great public places have within them common spaces in which the shooter can safely trust to such luck, areas where the general cross-traffic of humanity guarantees at least a fatter crop of opportunity for happy marriages between passersby and props. At Boston’s elegant Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, the surrounding walls of the central court are the main public collecting point, with hundreds of visitors framed daily by the arched windows and the architectural splendor of a re-imagined 15th-century Venetian palace. The couple seen here are but one of many pairings observable in a typical day.

The pair just happens to come ready-made, with enough decent luck assembled in one frame for almost anyone to come away with a half-decent picture. The size contrast between the man and the woman, their face-to-face gaze, their balanced location in the middle arch of the window, and their harmony with the overall verticality of the frame seem to say “mission accomplished”. I don’t need to know their agenda: they could be reciting lines of Gibrhan to each other or discussing mortgage rates: visually, it doesn’t matter. At the last instant, however, the seated woman, in shadow just right of them, presents some mystery. Is she extraneous, i.e., a spoiler, or does she provide a subplot? In short, story-wise, do I need her?

I decide that I do. Just as it’s uncertain what the couple is discussing, it’s impossible to know if she’s overhearing something intimate and juicy, or just sitting taking a rest. And I like leaving all those questions open, so, in the picture she stays. Thus, what you see here is exactly one out of one frame(s) taken for the hell of it. Nothing was changed in post-production except a conversion to monochrome. Turns out that even the possibility of budding romance can’t survive the distraction of Mrs. Gardner’s amazing legacy seen in full color, and the mystery woman is even more tantalizing in B&W. Easy call.

As we said at the beginning, working with my own formal rules of composition, I could easily have concluded that my picture would be “ruined” by my shadowy extra. And, I believe now, I would have been wrong. As photographers, we try to look out for our own good, but may actually know next to nothing about what that truly is.

And then the fun begins….

INCIDENTALS, ACCIDENTALS AND D.L.s

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU CAN’T BEGIN TO WRITE THE STORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY without acknowledging the role of the fortunate accident in the output of, well, everyone. Anyone who says he’s never been handed a rose from Lady Luck from time to time is either delusional or a dead-on liar. If we admit that chance occasionally turns our best plans to piddle, why not admit that we also randomly wind up in the winner’s circle on a free pass?

Here’s my freebie for probably the rest of this year, as I can’t see the triple crown of incidentals, accidentals and dumb luck converging as they did here anytime soon. Let’s look at the recipe in detail:

1: Accidentals. While walking along the edge of a footbridge alongside Tempe Town Lake in Arizona, I spooked a small flock of birds resting out of sight just beneath my feet. I heard them flee before I saw them head into open water.

2. Incidentals. For reasons I still can’t fathom, the birds did not take to the air, as you might expect, but escaped across the water, creating gorgeously trailing coils of ripples as they went. That slowed everything down enough that my startled synapses rebooted and started to shout, get your camera up to your eye. That led me to the one element that made the crucial difference, known to us all as:

3. Dumb Luck. After a lens change, I had walked almost a mile from my car when I realized that I had forgotten to slap on a polarizing filter, making shots across water in the sun of an Arizona midday almost guaranteed to saturated with glare. I had already improvised a crude hack my taking off my clip-on sunglasses and holding them in front of my lens. This had only intermittently worked, since I either left part of the field of view uncovered, or failed to hold the specs at the right angle, incurring wild variances in polarizing. As soon as my animal brain realized that I had one shot before my bird water ballet was out of reach, I had to frame, focus (I was already at f/8, so there was some help there), and get the sunglasses in position without deforming all that blue. Even at that, there’s quite a difference between the rendering of color in various parts of the frame.

What you see here, then, is the photo goddesses throwing me a bone. A big bone. We’re talking the rear haunch of a triceratops.

But, yeah, I’ll take it.

RE-PURPOSING INFORMATION

SIGNS ARE PRIMARILY SOURCES OF INFORMATION AND IDENTIFICATION, a utilitarian way of learning who’s who and what’s where. In photography, their primary use can move beyond those roles to become commentary, context, atmosphere, even pure abstract subject matter. As shooters, we all use signs in ways that are not strictly literal but are 100% visual. They are powerful tools.

This is a circular way of saying that, in an image, a sign is never just a sign, but a way of indicating and qualifying place, time, mood. Be it a hand-scrawled “keep out” warning outside a busted farmhouse or a day-glo neon “open” greeting outside a pawn shop, a sign is valuable narrative shorthand. Of course, just like human storytellers, some signs are untrustworthy narrators, undermining what they seem to “say” with the things they imply within an image. Managing their messaging then becomes the responsibility of the photographer, who can use their content to reveal, conceal, or comment as needed.

The sign seen here, announcing the Museum Of The Moving Image in Astoria,Queens, has its letters mounted on a mirror-like surface, allowing the viewer to see evolving street life over his shoulder as he “reads” the characters. It’s both advertisement and illustration, a low-tech demo of the museum’s intent. Like all signs, it’s a prop, a piece of stage dressing, interpreted as narrowly or broadly as you need it to be.

TWO WORLDS, ONE WALL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHS BEGAN AS A SIMPLE HEAD–ON ENGAGEMENT. The viewpoint of the camera was essentially that of an audience member viewing a stage play, or reading a page of text, with all visual information reading from left to right. People stood in front of the lens in one flat plane, giving the appearance, as they posed before offices or stores, that they themselves were components in a two-dimensional painting. Everyone stared straight ahead as if in military formation or a class portrait, producing fairly stiff results.

We started photography by placing people in front of walls, then learned, like good stage managers, that selectively positioning or moving those walls could help image-makers manage the techniques of conceal/reveal. Now you see it, now you don’t. Photography no longer takes place in one plane: barriers shift to show this, or to hide that. They are part of the system of composition. Control of viewing angle does this most efficiently, as in the above image, where just standing in the right place lets me view both the front and back activities of the restaurant at the same time.

Of course, generations after the rigid formality of photography’s first framing so, we do this unconsciously. Adjusting where walls occur to help amplify our pictures’ narratives just seems instinctive. However, it can be helpful to pull back from these automatic processes from time to time, to understand why we use them, the better to keep honing our ability to direct the viewer’s eye and control the story.

SLAGIATT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I CALL IT NO–FUNDAY, the painful exercise of poring over photographs that I once considered “keepers” and now must reluctantly re-classify as “obviously, I’m an idiot.” For any photographer, self-editing one’s output is just the kind of humiliation one needs to keep on shooting, if only to put greater distance between one’s self and one’s yester-duds.

To make the shame of disowning my photographic spawn even worse, I find that, more often than not, technical failure is usually not the reason I’m lunging for the delete button: it’s the weakness of the conception, a basic lifelessness or lack of impact that far outweighs any errors in exposure, lighting, even composition. In other words, my worst pictures are, by and large, bad because they are well-executed renditions of measly ideas.

In my mental filing cabinet, I refer to these images under the acronym SLIGIATT, or Seemed Like A Good Idea At The Time. The image above is a perfect example. This shot, taken inside the underbelly of a WWII bomber, presented a ton of lighting challenges, but I spent so much time tweaking this aspect of it that I neglected to notice that there just isn’t a picture here. It tells no story. It explains nothing. It’s just an incomprehensible jumble of old equipment which lets the eye wander all over the frame, only to land on…..well, what exactly? But, boy howdy, it is well-lit.

SLIGIATT photos are, of course, necessary. You have to take all the wrong pictures to teach yourself how to create the good ones. And mere technical prowess can, for a time, resemble quality of a sort. But technique is merely craft, and can be had rather easily. The art part comes in when you’re lucky enough to also build a soul into a machine. As Frankenstein figured out, that’s the difference between being God and playing God.

SHATTERING THE FRAME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST REVOLUTIONARY ACTS a photographer can commit is the thwarting of expectation, a deliberate subverting of what the viewer assumes will happen next. Composition-wise, this means not just deciding what information makes it into the frame, but, indeed, whether there will even be a frame at all.

Any demarcation or line within an image can be used to direct attention to a given location. Whether including or excluding, pointing toward or pointing away from, the photographer has pretty much limited authority on how he’ll direct traffic within a composition. And so we shoot through holes, slats, panes, and skylights. We observe borders marked by cast shadows: we cut spaces in half to make two rooms out of one: we reveal facts in parts of reflections while obscuring the objects they reflect.

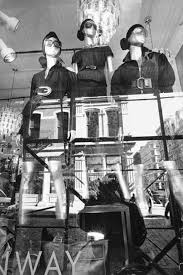

In the above image, I saw the subdivisions of the department store display unit like a wall of little tv’s, each screen showing its own distinct mini-drama. Is the woman seen eyeing the merchandise the most prominent “screen star”, or are we just seeing an arbitrary mosaic of the larger scene behind the display? Or is it both?

Framing within the larger frame of a composition can isolate and boost whatever message we’ve chosen to convey, and it’s perhaps the most total control a photographer can wield, more so in its way than even exposure or lighting.

AND NOW WE PAUSE FOR…

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A BREAK IN THE ACTION: a word from our sponsor: a coda before the chorus. Intrusions into the predictable rhythms of things can be either annoying or refreshing, depending on how we perceive them.

The right intervals between dots and dashes can drastically change the meaning of a telegram. A well-placed silence between musical notes can generate just the tension required to transform a composition into a masterpiece. And a sudden interruption in visual patterns can add impact to a photograph.

Once the eye detects, as they say on Sesame Street, that one of the things in a picture is not like the others, it pauses, re-evaluating every element in the scene, weighing it for relative value. Breaking an image’s pattern is either an unwelcome invasion or a kind of visual punctuation….again, varying as to the effect. The object violating the uniformity says pause, wait, re–consider, and begins a new conversation about what we’re seeing and what we think about it.

In the above picture, a human silhouette against the massive ceiling grid provides the basic context of scale, and defines the locale (a library) as a space where human activity takes place. The figure thus says how big the place is and what it is for, along with any other ancillary associations touched off in the viewer’s mind. Would the picture “work” without the figure? Certainly. The terms of engagement would just be different, that’s all.

Photographs are not merely pictures of things. They are also sets of instructions (suggestions?) on what to do with all that information. Think of them like roadside signs. It’s indeed helpful to be told, for example, that Sacramento is just another 100 miles away. But it’s just as important to have a big bright arrow telling you to head that–away.

PERFECT VS RIGHT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

OUR VERY HUMAN DESIRE TO MAKE OUR PHOTOGRAPHY TECHNICALLY FLAWLESS can be observed in the results you can glean from a simple Google search of the words “perfect” and “photos”. Hundreds of tutorials and how-tos pop up on how to get “the perfect portrait”, “the perfect family picture”, “the perfect sunset”, and of course, “the perfect wedding shot”. The message is all too clear; when it comes to making pictures, we desperately want to get it right. But how to get it right…that’s a completely different discussion.

Because if, by “perfect”, we means a seamless blend of accurate exposure, the ideal aperture, and the dream composition, then I think we are barking up a whole forest of wrong trees. Mere technical prowess in photography can certainly be taught, but does obeying all these rules result in a “perfect” picture?

If you stipulate that you can produce a shot that is both precise in technique and soulless and empty, then we should probably find a more reasonable understanding of perfection. Perfect is, to me, a word that should describe the emotional impact of the result, not the capital “S” science that went into its execution. That is, some images are so powerful that we forget to notice their technical shortcomings. And that brings us to the second part of this exercise.

Can a flawed image move us, rouse us to anger, turn us on, help us see and feel? Absolutely, and they do all the time. We may talk perfection, but we are deeply impressed with honesty. Of course, in two hundred years, we still haven’t shaken the mistaken notion that a photograph is “reality”. It is not, and never was, even though it has an optical resemblance to it. It became apparent pretty early in the game that photographs could not only record, but persuade, and, yes, lie. So whatever you shoot, no matter how great you are at setting your settings, is an abstraction. That means it’s already less than perfect, even before you add your own flaws and faults. So the game is already lost. Or, depending on our viewpoint, a lot more interesting.

Go for impact over perfect every time. You can control how much emotional wallop is packed into your pictures just as surely as you can master the technical stuff, and pictures that truly connect on a deep level will kick the keester of a flawless picture every single time. The perfect picture is the one that brings back what you sent it to do. The camera can’t breathe life into a static image. Only a photographer can do that.

JUMPING OFF THE TOUR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

VISITOR ATTRACTIONS CREATE THEIR OWN KIND OF PECULIAR GRAVITY, in that many of them develop an “official” way to take in their delights, pulling you toward what they believe to be the center of things. From the creation of tourist maps to the arrangement of signs on paths, many famous “places to see” evolve systems for how to “do” parks, recreation areas, even ancient ruins. Some hot spots have even been so obvious as to mount signage right next to the “Kodak moment” view that, of course, you will want to to snap, since everybody does. And from here, folks, you can clearly see the royal castle, the original temple, the stunning mountain vista, etc., etc.

But predictability, or an approved way of seeing a particular thing, is the death of spontaneity, and certainly a danger signal for any kind of creativity. Photography is the visual measure of our subjective experience. It’s supposed to be biased toward our individual way of taking a thing in. Grading our reactions to visual stimuli on the curve, taking us all down the same path of recommended enjoyment, actually obviates the need for a camera. Just freeze the “correct” view on the gift store’s postcard assortment, and, presto, we can all have the same level of enjoyment. Or the same low point of banality.

Recently I visited the amazing Butchart Gardens, a botanical bonanza on the island of Victoria in British Columbia. If ever there was a place where you’d be tempted to tick off “the sights” on a mental checklist, this cornucopia of topiary choreography is it, and you will find it truly tempting not to attempt your “take” on its most photographed features. But an experience is not a triptych, and I found my favorite moments were near the fringes or niches of the property, many of which are as stunning as the most traveled wonders along the approved paths.

To my great surprise, my favorite shot from the tour wasn’t one of the major sites or even a color image, but a quick glimpse of a young girl hesitating in the narrow, arched portal that separated one side of an enormous hedge from the other. She only hesitated for a few seconds before walking into the more traveled courtyard just adjacent, which is, itself, recorded thousands of times a day. But that brief pause was enough. She had become, to me, Alice, dawdling on the edge of a new Wonderland. The arch became all mystery to me, but the picture needed to be simplified to amplify that feeling, relegating the bright hues to secondary status. And while it indeed seems counterintuitive to take a black and white image in the midst of one of the world’s great explosions of color, I gladly chose the mono version once I had the chance to compare it to the original. Some things just work.

One thing that never works is trying to make your personal photographs conform with what the designer of a public place has recommended as the essential features of that place. Your camera is just that….your camera. Shoot with someone else’s eye, and you might as well just frame the brochure.

THE LOVE OBJECT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN EARLIER OUTINGS, WE HAVE DISCUSSED THE VALUE of knowing how sunlight enters your house at all times of the day. Knowing where bright spots and slatted beams hit the interior of your home in different hours gives you a complete map of “sweet spots” where natural light will temporarily isolate and flatter certain objects, giving you at least several optimized minutes for prime shooting each day.

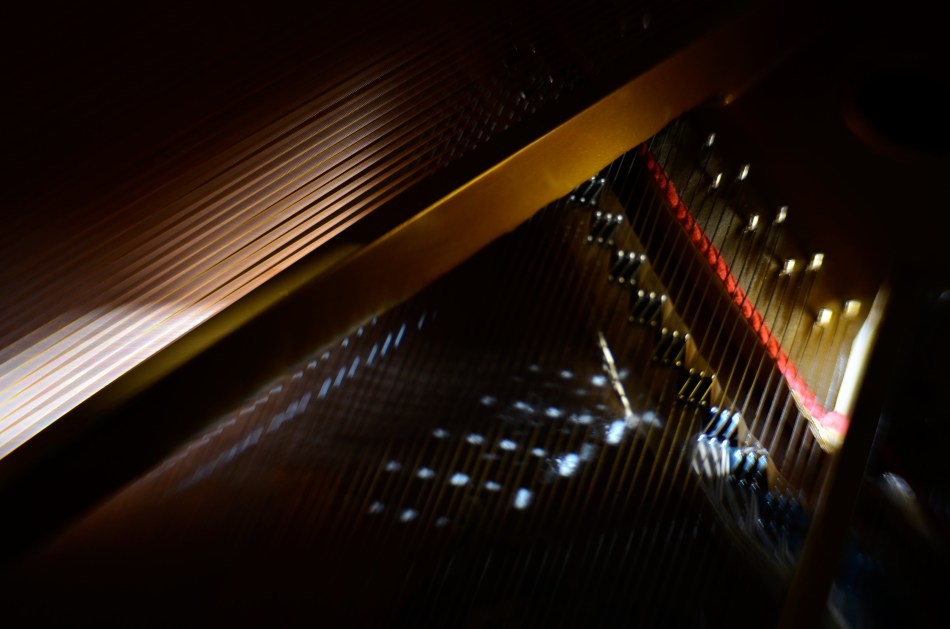

Keeping this little time-table in your head allows you to move your subjects to those places in the house where, say, the daily 10 a.m. sun shaft through the family room window will give you a predictably golden glow. For me, that location is my living room window, across which the southwestern sun tracks east/west, and the object is my white baby grand piano.

Pianos, to me, are divinely complex gadgets, creations of the first great industrial age, their impossibly intricate mechanics offering thousands of possibilities for macro shots, fisheye explosions, abstract compositions, shadow studies, and delicate ballets of reflections as the morning sun dances across harp, strings, and hammers in an endless kaleidoscope of radiance. I have long since tracked how the sun showcases different parts of the piano as the day progresses, and how that corresponds to the instrument’s various sections and subsections.

Hard-wiring that schedule into my skull over the years means I know when a shot will work and when it won’t, making the object more than just something to shoot. It becomes, in effect, an active kind of photo laboratory, a way of teaching and re-teaching myself about the limits of both light and my own abilities. Better still, the innate intricacy of the piano as an object guarantees that I can never really get “done” with the project, or that something that was a mystery in January will become a revelation by June.

What gives this process a special lure to me is my endless effort to exploit natural light to the full, believing, as I do, that nearly every other less organic form of illumination is measurably poorer and less satisfactory than that which comes plentifully, and for free. The house I live in has thus become, over the years, a kind of greenhouse for the management of light, an active farm for harvesting the sun.

BLUR IS THE NEW SHADOW

Modern art lenses allow different parts of objects that are all in one focal plane to be selectively blurred.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’M INCREASINGLY FASCINATED BY PHOTOGRAPHS THAT SUPPRESS INFORMATION, choosing to selectively conceal details rather than merely delineate everything in the frame in the same exhaustively sharp detail. At the same time, I hate it when this technique is referred to as being “painterly”, as if, after all this time, photos are still striving for the same pedigree that daubers automatically inherit merely by picking up a brush. Photographs are not, and should not try to be, paintings, just as a shoe should not try to pass as a glove. Love the function of the art you have, and leave the mimicry to the mockingbirds.

The “painterly” tag used to be tied mainly to anyone shrouding their images in shadow, as if we were all bucking to be the next Rembrandt or Reubens. And certainly the use of darkness in photography creates a kind of mysterious minimalism, telling more by showing less. We linger over what’s left out of a photo, and the deliberate subtraction of detail simplifies a composition to its barest terms. When there is less to see, you eye goes like a laser to what remains. It’s a big, bright “this way, dummy” arrow pointing toward the heart of the picture.

In the same way, the current wave of photographers are using blur to punch up the impact of images. Any Google search of the phrase “blur my photos” unearths a wellspring of apps that allow any part of any frame to be selectively de-focused, in most cases (as happens with apps) after the picture is taken. Long regarded as the stuff of artifact or accident, blur is now being arranged, managed, and chosen as a tool to remove distracting detail from compositions, or to render them softer and more intimate. In the above image, separate elements of the structure, all of which lie generally in the same focal plane, can be selectively softened so that one can become dominant, while the other is abstracted. This particular shot is done with a Lensbaby Sweet 35 lens, which allows the “sweet spot” of focus to be rotated to any location the shooter desires, although there are many paths to similar results.

Both apps and lenses, which include newly reworked versions of old optics, offer a return to the randomness from which early photographers longed to escape. Lomography, the revival of flawed and cheap cameras from the film era, actually touts blur as a strength, an arty accent much to be desired. To be totally counter-intuitive about it, blur is edgy. Of course, some blur is just another kind of visual noise, and if it’s applied too carelessly or too much, it actually pulls the eye away from the main message of a picture. However, it’s thrilling just to see the sheer breadth of approaches that are suddenly available everywhere, most of them cheap, fast and easy. Blur can “sharpen” a picture just like darkness can “illuminate” one. It’s the new shadow.

TEN NO’s AND A YES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE CERTAINLY MANY MORE PICTURES BEING TAKEN than there are great pictures taken. That’s as it should be. Anything at which you wish to be excellent only comes about once you’ve learned what not to do, and that means lots of errors, lots of images that you feel compelled to destroy almost as quickly as you’ve created them. You must, must, must, take all the bad pictures right alongside the good ones. At first, the garbage will outnumber the groceries.

And then, some day, it doesn’t.

I am an A.B.S. (Always Be Shooting) shooter. I mean, I make myself at least try to make a picture every….single…day. No excuses, no regrets, no exceptions. Reason? I simply don’t know (and neither do you) where the good pictures are going to come from. For me to give myself permission not to try on a given day means I am risking that one of those potentially golden pictures will never be born. Period period period.

In a way, I often think photo technique guides from years gone by had things backwards. That is, they often made suggestions of great opportunities to take great pictures. You know the list: at a party: on a vacation: to capture special moments with loved ones, etc., etc. However, none of these traditional “how-to” books included a category called “just for the hell of it”, “why not?”, or, in the digital era, “whattya got to lose? You’re shooting for free!” These days, there are virtually no barriers to making as many pictures as you want, quickly, and with more options for control and creativity, both before and after the shutter click. So that old “ideas” list needs to be re-thought.

To my thinking, here’s the one (yes, I said ONE) suggestion for making pictures, the only one that matters:

TAKE THE SHOT ANYWAY.

And to purify your thinking, here’s my larger list, that of the most commonly used excuses not to shoot. You know ’em. You’ve used ’em. And by doing so, you’ve likely blown the chance at a great picture. Or not. You won’t know, because you didn’t TAKE THE SHOT ANYWAY. Here are the excuses, in all their shameful glory:

I haven’t got the right lens/camera/gear. There’s not enough light. I don’t do these kinds of pictures well. I don’t have my “real” camera. There’s nothing to take a picture “of”. Everyone takes a picture of this. I’ll do it later. It probably won’t be any good. There are too many people in the picture. There isn’t enough time.

Train yourself to repeat take the shot anyway, like a mantra, whenever any of these alibis spring into your head. Speed up your learning curve. Court the uncertain. Roll the dice. Harvest order from chaos. Stop waiting for your shot, your perfect day, your ideal opportunity.

Take the shot. Anyway.

TRUTH VS. REALITY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ASKED IN 1974 BY AN INTERVIEWER ABOUT THE LEGACY OF THE ACTOR JAMES CAGNEY, director Orson Welles replied that while Jimmy “broke every rule”, “there’s not a fake moment” in any of his movies. He further explained that the star of Public Enemy, White Heat and Yankee Doodle Dandy worked counter to all the conventions of what was supposed to be “realism”, and yet created roles which were absolutely authentic. Cagney, in effect, bypassed the real and told the truth.

As do many photographers, it turns out.

We all have inherited a series of technical skills which were evolved in an attempt to capture the real world faithfully inside a box, and we still fail, at times, to realize that what makes in image genuine to the viewer must often be achieved by ignoring what is “real”. Like Cagney, we break the rules, and, if we are lucky, we make the argument that what we’ve presented ought to be considered the truth, even though the viewer must ignore what he knows in order to believe that. Even when we are not trying to create a so-called special effect, that is, a deliberate trick designed to conspicuously wow the audience, we are pulling off little cheats to make it seem that we played absolutely fair.

The first time we experiment with lighting, we dabble in this trickery, since the idea of lighting an object is to make a good-looking picture, rather than to mimic what happens in natural light. If we are crafty about it, the lie we have put forth seems like it ought to be the truth, and we are praised for how “realistic” a shot appears. The eye likes the look we created, whether it bears any resemblance to the real world or not, just as we applaud a young actor made up to look like an old man, even though we “know” he isn’t typically bald, wrinkled, and bent over a cane.

In the image above, you see a simple example of this. The antique Kodak really does have its back to a sunlit window, and the shadows etched along its body really do come from the slatted shutters upon that window. However, the decorative front of the camera, which would be fun to see, is facing away from the light source. That means that, in reality, it would not glow gold as seen in the final image. And, since reality alone will not give us that radiance, a second light source has to be added from the front.

In this case, it’s the most primitive source available: my left hand, which is ever so slightly visible at the lower left edge of the shot. It’s acting as a crude reflector of the sunlight at right, but is also adding some warmer color as the flesh tones of my skin tint the light with a little gold on its way back to the front of the camera. Result: an unrealistic, yet realistic-seeming shot.

There’s a number of names for this kind of technique: fakery, jiggery-pokery, flimflam, manipulation, etc., etc.

And some simply call it photography.

COMPOSING ON THE RUN

An instinctual snap: sunset light on a forest path. And that’s that….or is it?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LOTS OF OUR BEST PHOTOGRAPHS ARE, EXCUSE THE EXPRESSION, snap judgements. Sometimes a composition simply seems to come fully formed, ready to jump intact into the camera, with no reasonable way to improve on a shot that is 99% pure impulse. Some of these gift moments are so seductive that we may not think to keep shooting beyond what we’ve perceived as the ideal moment. But more shooting may be just what we need.

Images that involve very fast-moving events may only have one key instant where the real storytelling power of the shot comes to a climax, with everything after seen as progressively less dramatic. The second after a baseball is hit: the relaxed smile after the birthday candles are blown out. Think, if you will, of a straight news or journalism image. Every second after the Hindenburg explodes is less and less intense.

But many images can be re-imagined second-by-second, with additional takes offering the photographer vastly different outcomes and choices. In the series shown here, I originally fell in love with the look of sunset on a wooded trail. My first instinct was that the receding path was everything I needed, and I shot the first frame not thinking there would even be a second. My wife, however, decided to walk into the space unexpectedly, and I decided to click additional frames every few seconds as she walked toward the shot’s horizon. She starts off in the lower right corner and walks gently left as she climbs the slight rise in the path, causing her hair to catch a sun flare in the second shot, and placing her in central importance in the composition. By the last shot, however, she is a complete silhouette at the top of the frame, taking her far enough “up” to restore the path to its original prominence with her as a mere accent.

Which shot to take? Anyone’s call, but the point here is that, by continuing to shoot, I had four images to choose from, all with very individualized dynamics, none of which would have been available to me if I’d just decided that my first shot was my best and settled. There will be times when the fullest storytelling power of a photograph is all present right there in your first instinctive snap. When you have time, however, learning to compose on the run can force you to keep re-visualizing your way to lots of other possibilities.

ARRIVALS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS PROBABLY HAVE TO HAVE AT LEAST SOME IDEA OF WHERE THEY’RE HEADED in pursuit of an image, or else basic issues like, Where To Point The Car or Which Path To Take can’t be settled. And there is, even for the instinctual process of creation, something to be said for a basic plan. However, every photographer has experienced the wonder of finding oneself arrived at a great picture-making opportunity when, in fact, you were headed someplace completely different. It’s in such moments, places where Plan A becomes Plan B, C, or D, that the excitement happens.

After you capture an image that essentially works, your mind naturally comes to take ownership of it, just as if that picture were your original intention. But this seldom occurs. Pictures aren’t like Grab-And-Go sandwiches, and very few are just waiting there, fully formed, until you wander by and imprison them in your box. Our final choices for photographs are often the destination in a ride with many stops along the way. We might have come to do this, but we wound up modifying, even abandoning our first instinct to get this instead.

The above image is a textbook example of this process. The gorgeous sunset clouds seen here were originally to be the entire composition. The general rule is that skies, by themselves, are usually not sufficiently interesting to be the solo star in a photo, but the light and texture of this particular dusk had convinced me that a minimalist shot might just be possible. However, one of my first framings caught an octotillo shrub in its lower right corner, and that new information sent the picture off in a different direction.

Re-framing to bring the shrub into the entire lower half of the shot and silhouetting it against the sky gave the framing both a sense of scale and depth, and I began to convince myself (moving on to Plan B) that this now two-element picture would be The One. Then a single starling made a landing at the upper right corner of the ocotillo, creating a more obvious initial point of contact for the eye. The viewer would engage the most familiar part of the picture, the bird’s body, then travel leftward to the ocotillo’s jagged tangles, and backwards to the textured sky. Final Plan: C….a three-element image in which the individual parts seemed, at least, to talking with one another.

In the pages of The Normal Eye I keep coming back to this idea of “planned accidents”, or shots that start in one direction and end in another, because the process, once you allow yourself to go with it, can lead to images which, eventually, seem inevitable, as if they never could have been any other way. And those are the ones you keep.

INSIDE THE IRIS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN ONE OF HIS EARLIEST SILENT FILMS, legendary director D.W. Griffith, one of the first cinematic pioneers to use tight shots to highlight vital narrative details, drew fire from theatre exhibitors, who objected to his new-fangled “close-up” or “iris” technique. “We have paid for the entire actor”, one wrote, apparently of the opinion that showing only a player’s hand or face, even in the interest of a good story, was somehow short-changing the audience. Griffith knew better, however. He was using his compositional frame to tell his viewers, in no uncertain terms, what was important. Outside the frame was all the other stuff that mattered less. If I show it, you should pay attention.

Photography is not so much about whether a subject is intrinsically important (think of the apple in a still-life) but whether an artist, armed with a camera and an idea, can make it important. At the dawn of the medium, painters pretty much dominated the choices about which images were immortalized as emblematic of the culture. The subject matter often ran to big targets; war, portraits of the elite, historical and religious events. And, indeed, the earliest photographs were “about something”, the “somethings” often being documents of the world’s wonders (pyramids, cathedrals) fads (politicians, authors) and foibles (crime, the occasional disaster). Subjects were selected for their importance as events, as leaves of history worthy of preservation.

In the 20th century the same abstract movements that engulfed painting allowed photography to cast a wider net. Suddenly that apple in the bowl was a worthy, even a vital subject. Light, composition, angle and mood began to weigh as heavily as the thing pictured. We made images not because the objects looked right, but because they looked right when made into a photograph. Pictures went from being about what “is” to being about what could be….evoking, like poetry, music or literature the magics of memory, dream, potentiality, emotion.

This is really the ultimate freedom of not only photography, but of any true art; the ability to confer special status on anything, anywhere. That doesn’t mean that all photographs are now of equal value; far from it. The burden of proof, the making of the argument for a particular subject’s preservation in an image, still rests squarely on the shooter’s shoulders. It’s just not necessary to wait for a natural disaster, a ribbon cutting, or a breathless landscape to make an amazing photograph. The eye is enough. In fact, it’s everything.

THE RIGHT PICTURE IN THE RIGHT FRAME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

COMPOSITION IN PHOTOGRAPHY, FOR MANY OF US, CAN OFTEN INVOLVE NOTHING MORE than finding a thing we want to capture and getting it all in the frame. Click and done. It’s only later that we sometimes realize that we should have, shall we say, shopped around for the best way, from angle to exposure, to get our quarry in frame. Or even look for a better frame.

One of the first tricks I learned in travel photography was from the old scenic shooters who created the travel titles for View-Master Reels, who always thought in terms of framing to maximize the image’s 3-d effect. For a start, since they were working in square format, they automatically had less real estate in which to compose. Secondly, they had to shoot in “layers”, since the idea was to have subject matter in multiple planes, for example, overhanging shade tree right at the front, a tourist midway into the shot, and Mount Rushmore at the back. They also learned to position things just inside the frame’s edge, what was called the “stereo window” to accentuate the sensation of looking into the photograph.

Thing is, all of these compositional techniques work exactly the same in a flat image, and can draw the viewer’s eye deeper into a picture, if used creatively. Certainly you can’t go wrong with a great exposure of a beautiful view. But experiment as well with things that force your audience to peer intently into that view. The image at the top is standard post-card, and works well enough. However, in the shot at left, in taking ten seconds to slip inside a gift shop that also looks out on the same view, I’ve tried to show how you can get an atmospheric framing that both accentuates depth and provides a bit more of a sense of destination. It all depends on what you’re looking to do, of course….but it makes sense to develop the habit of asking yourself how many different ways are available to tell the same story.

Editing a solid portfolio of shots can only begin with lots of choices. Hey, you’re there, anyway, so develop the habit of envisioning multiple versions of each picture, and weed out what doesn’t work. Remember again that the only picture that absolutely fails is the one you didn’t try to make.

TWO-WAY GLASS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF THE EYES ARE THE WINDOW TO THE SOUL, then certain windows are an eye into contrasting worlds.

Photographers have devised a wide number of approaches when it comes to using windows as visual elements. Many choose to shoot through them with a minimum of glare, as if the glass were not there at all. Others use them as a kind of surreal jigsaw puzzle of reflected info-fragments.

To show these two approaches through the eyes of two great photographers, examine first Eugene Atget’s shots of 19th-century Paris storefronts, which mostly concentrated on shopkeeper’s wares and how they were arranged in display windows. Straightforward, simple. Then contrast Lee Friedlander’s 21st-century layered blendings of forward view and backward reflection (seen at left), which suspends the eye between two worlds, leaving the importance of all that mixed data to the viewer’s interpretation.

Much of my own window work falls into the latter category, as I enjoy seeing what’s inside, what’s outside, and what’s over my shoulder, all in the same shot. What’s happening behind the glass can be a bit voyeuristic, almost forbidden, as if we are not fully entitled to enter the reality on the other side of the window. But it’s interesting as well to use the glass surface as a mirror that places the shop in a full neighborhood context, that reminds you that life is flowing past that window, that the area is a living thing.

Thus, in an urban setting, every window is potentially two-way glass. Now, just because this technique serves some people as a narrative or commentary doesn’t make it a commandment. You have to use the language that speaks for you and to your viewer. Whatever kind of engagement serves that relationship best dictates how you should be shooting. I just personally find layered windows a fun sandbox to play in, as it takes the static quality away from a still photo to some degree, as if the image were imbued with at least the illusion of motion.

Sometimes it’s good to conceal more than reveal, and vice versa. The only “must”, for this or any other technique in photography, is to be totally mindful as you’re creating. Choose what you mean to do, and do it with your eyes fully open.

SPHERE ITSELF

Wet Democracy (2017): The 1964 World’s Fair’s central icon as play space.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CULTURAL ICONS, which burn very distinct patterns into our memory, can become the single most challenging subjects for photography. As templates for our key experiences, icons seem to insist upon being visualized in very narrow ways–the “official” or post card view, the version every shooter tries to emulate or mimic. By contrast, photography is all about rejecting the standard or the static. There must be, we insist, another way to try and see this thing beyond the obvious.

Upon its debut as the central symbol for the 1964 New York World’s Fair, the stainless steel structure known as the Unisphere was presented as the emblem of the peaceful ideals put forth by the Exhibition’s creators. Under the theme “Peace Through Understanding”, the Uni, 120 feet across and 140 feet in height, was cordoned off from foot traffic and encircled by jetting fountains,which were designed to camouflage the globe’s immense pedestal, creating the illusion that this ideal planet was, in effect, floating in space. Anchoring the Fair site at its center, the Unisphere became the big show’s default souvenir trademark, immortalized in hundreds of licensed products, dozens of press releases and gazillions of candid photographs. The message was clear: To visually “do” the fair, you had to snap the sphere.

After the curtain was rung down on the event and Flushing Meadows-Corona Park began a slow, sad slide toward decay, the Unisphere, coated with grime and buckling under the twin tyrannies of weather and time, nearly became the world’s most famous chunk of scrap metal. By 1995, however, the tide had turned; the globe was protected by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, and its rehabilitation was accompanied by a restoration of its encircling fountains, which were put back in service in 2010. The fair park, itself staging a comeback, welcomed back its space-age jewel.

As for photography: over the decades, 99% of the amateur images of the Unisphere have conformed to the photographic norm for icons: a certain aloof distance, a careful respect. Many pictures show the sphere alone, not even framed by the park trees that flank it on all sides, while many others are composed so that not one of the many daily visitors to the park can be seen, robbing this giant of the impact imparted by a true sense of scale.

In shooting Uni myself for the first time, I found it impossible not only to include the people around it, but to marvel at how completely they now possess it. The decorum of the ’64 fair as Prestigious Event now long gone, the sphere has been claimed for the very masses for whom it was built: as recreation site, as family gathering place..and, yes, as the biggest wading pool in New York.

This repurposing, for me, freed the Unisphere from the gilded cage of iconography and allowed me to see it as something completely new, no longer an abstraction of the people’s hopes, but as a real measure of their daily lives. Photographs are about where you go and also where you hope to go. And sometimes the only thing your eye has to phere is sphere itself.

Share this:

July 29, 2017 | Categories: Americana, Arts, Cities, Commentary | Tags: American History, Composition, New York, World's Fairs | Leave a comment