SHADOWS AS STAGERS

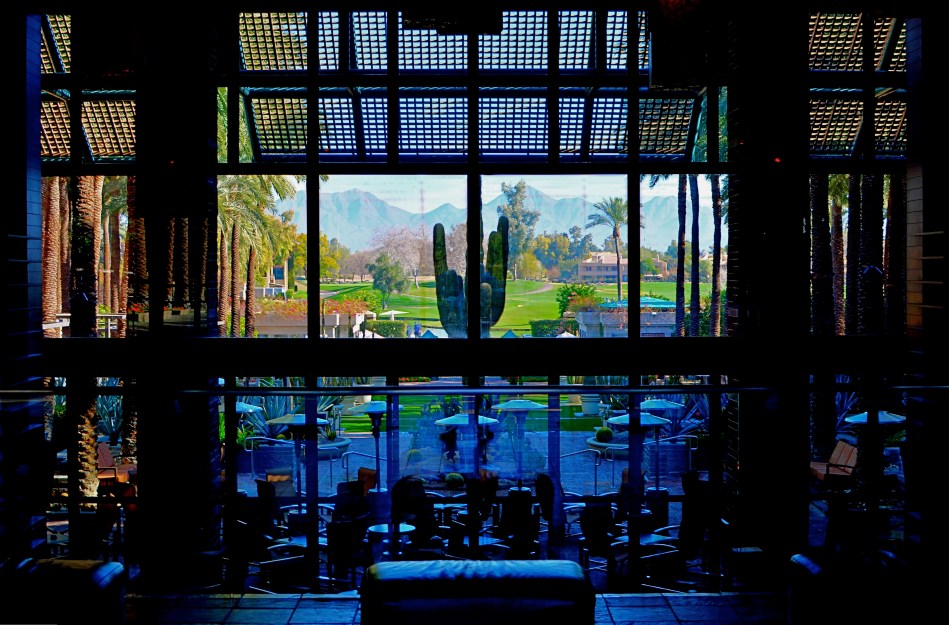

The idea of this image is to highlight what lies beyond the window framing, not the objects in front of it. Lighting should serve that end.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THOSE WHO ADHERE TO THE CLASSIC “RULE OF THIRDS” system of composition often suggest that you imagine your frame with a nine-space grid super-imposed over it, the better to help you place your subject in the greatest place of visual interest. This place is usually at the intersection of several of these grid lines, and, whether or not you strictly adhere to the “thirds” system, it’s useful to compose your shots purposefully, and the grid does give you a kind of subliminal habit of doing just that.

Sometimes, however, I find that the invisible grid can be rendered briefly visible to become a real part of your composition. That is to say, framing through silhouetted patterns can add a little dimension to an otherwise flat image. Leaving some foreground elements deliberately underlit is kind of a double win, in that it eliminates detail that might read as clutter, and helps hem in the parts of the background items you want to most highlight.

These days, with HDR and other facile post-production fixes multiplying like rabbits on Viagra, the trend has been to recover as much detail from darker elements as possible. However, this effect of everything being magically “lit” at one even level can be a little jarring since it clearly runs counter to the way we truly see. It’s great for novel or fantasy shots, but the good old-fashioned silhouette is the most elemental way to add the perception of depth to a scene as well as steering attention wherever you need it. Shadows can set the stage for certain images in a dramatic fashion.

Cheap. Fast. Easy. Repeat.

COME EARLY / STAY LATE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PUBLIC SPACES OFTEN LOSE THEIR POWER AS GRAND DESIGNS once they actually are occupied by the public. If you have ever leafed through books of architectural renderings, the original drawings for squares, plazas, office buildings or other mass gathering places, the elegance of their patterns is apparent in a way that they cease to be, once they are teeming with commuters or customers.

This doesn’t mean that humans “spoil” the art of architecture, however, the overlay of drama and tension created by the presence of huge hordes of people definitely distracts from an appreciation of the beauty that is so clean and clear in a place’s sketch phase. Photographically, people as design objects tend to steal the scene, if you will, making public settings less dramatic in some ways. That’s why I like to make images of such locales when they are essentially empty, since it forces the eye to see design as the dominant story in the picture. I suppose that I’m channeling the great designers and illustrators that influenced me as a young would-be comic book artist. It’s a matter of emphasis. While other kids worked on rendering their superheroes’ muscles and capes correctly, I wanted to draw Metropolis right.

I recently began driving to various mega-resorts in the Phoenix, Arizona area to capture scenes in either early morning or late afternoon. Some are grand in their ambition, and more than a few are plain over-the-top vulgar, but sometimes I find that just working with the buildings and landscaping as a designer might have originally imagined them can be surprising. Taking places which were meant to accommodate large gatherings of people, then extracting said people, forces the eye to align itself with the original designer’s idea without compromise. Try it, and you may also find that coming early or staying late at a public area gives you a different photographic perspective on a site. At any rate, it’s another exercise in re-seeing, or forcing yourself to visualize a familiar thing eccentrically.

DETAILS, DETAILS

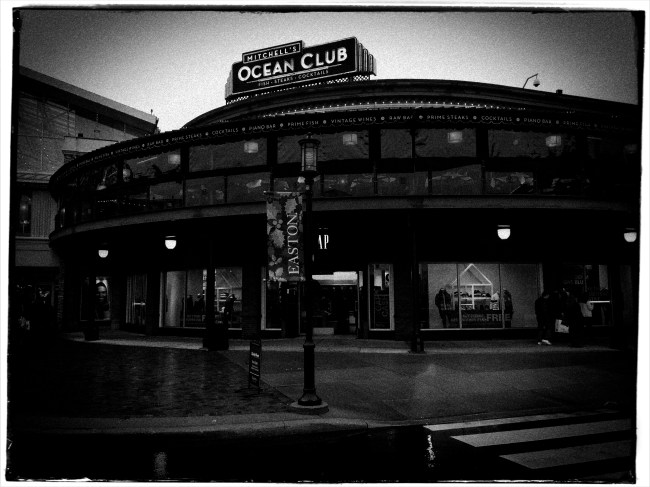

Moody, but still a bit too tidy. Black and white by itself wasn’t enough to create the atmosphere I wanted.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVEN THOUGH MOST GREAT PHOTOGRAPHERS PROCLAIM that any “rules” in their medium exist only to be broken, it’s often tough to chuck out regulations that have served you well over a lifetime of work. Once you get used to producing decent images through the repetition of habit, it takes extra nerve to take yourself outside your comfort zone, even if it means adding impact to your shots. You tend not to think of rules as arbitrary or confining, but as structural pillars that keep the roof from falling in.

That’s why it’s a good exercise to force yourself to do something that you feel is a bad fit for your style, lest your approach to everything go from being solid to, well, fossilized. If you hate black and white, make yourself shoot only monochrome for a week. If you feel cramped by square framing, make yourself work exclusively in that compositional format, as if your camera were incapable of landscape or portrait orientations. In my own case, I have to pry my brain away from an instinctual reliance on pinsharp focus, something which part of me fears will lead to chaos in my images. However, as I occasionally force myself to admit, sharp ain’t everything, and there may even be some times when it will kill, or at least dull, a picture.

With post-processing such an instantaneous, cheap, and largely effortless option these days, there really isn’t any reason to not at least try various modes of partial focus just to see where it will lead. Take what you believe will work in terms of the original shot, and experiment with alternate ways of interpreting what you started with.

In the shot at the top of this post, I tried to create mood in a uniquely shaped fish house with monochrome and a dour exposure on a nearly colorless day. Thing is, the image carried too much detail to be effectively atmospheric. The place still looked like a fairly new, fairly spiffy eatery located in an open-air shopping district. I wanted it to look like a worn, weathered joint, a marginal hangout that haunted the wharf that its seafood theme and design suggested. I needed to add more mood and mystery to it, and merely shooting in black & white wasn’t going to get me there, so I ran the shot through an app that created a tilt-shift focus effect, localizing the sharpness to the rooftop sign only and letting the rest of the structure melt into murk.

It shouldn’t be hard to skate around a rule in search of an image that comes closer to what you see in your mind, and yet it can require a leap of faith. Hard to say why trying new things spikes the blood pressure. We’re not heart surgeons, after all, and no one dies if we make a mistake.Anyway, you are never more than one click away from your next best picture.

FRAGMENTS AND SHARDS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

GLASS SURFACES REPRESENT A SERIES OF CHOICES FOR PHOTOGRAPHERS, an endless variety of effects based on the fact that they are both windows and mirrors, bouncing, amplifying or channeling light no less than any other subject in your frame. No two shooters approach the use (or avoidance) of glass as a compositional component in quite the same way. To some, it’s a barrier that they have to get past to present a clear view of their subject. To others, its fragments and shards of angle and light are part of the picture, adding their own commentary or irony.

I usually judge glass’ value in a photograph by two basic qualifiers: context and structure. First, context: suppose you are focused on something that lies just beyond a storefront window. What visual information is outside the scope of the viewer, say something over your shoulder or across the street, that might provide additional impact or context if reflected in the glass that is in direct view? It goes without saying that all reflections are not equal, so automatically factoring them into your photo may add dimension, or merely clutter things up.

The other qualifier is the structure of the glass itself. How does the glass break up, distort, or re-color light within an enclosure? In the above image, for example, I was fascinated by the complex patterns of glass in an auto showroom, especially in the way it reassigned hues once the sun began to set. I had a lot of golden light fighting for dominance with the darker colors of the lit surfaces within the building, making for a kind of cubist effect. No color was trustworthy or natural , and yet everything could be rendered “as is” and regarded by the eye as “real”. The glass was part of the composition, in this instance, and at this precise moment. Midday or morning light would render a completely different effect, perhaps an unwelcome one.

Great artists from Eugene Atget to Robert Frank have created compelling images using glass as a kind character actor in their shots. It’s an easy way to deepen the impact of your shots. Let the shards and fragments act like tiles to assemble your own mosaics.

LOOK DEEP INTO MY EYES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

3-D PHOTOGRAPHY SEEMS DOOMED TO FOREVER RESIDE ON THE PERIPHERY OF THE MEDIUM AT LARGE, a part of the art that is regarded with mild derision, a card trick, a circus illusion. My own experience in it, from simple stereoscopic point-and-shoots to high-end pro-sumer devices like the Realist or View-Master cameras, has met with a lot of frustration at the unavoidable technical barriers that keep it from being a truly sharable kind of photography. It’s rife with specialized viewers, odd goggles, and cumbrous projection systems. It calls attention to effect to the detriment of content. It is the performing seal of photography.

That said, the learning curve needed to compose for stereo effect is equally valuable for overall “flat” composition, since you must always be mindful of building layers of information from front to back, the better to draw your viewer’s eye deep into your subject. Some will meet this challenge with a simple selective depth of field, as if to say: only pay attention to the stuff that is sharp. The front/back/sides don’t matter…I’ll tell you where to look. Others decide to arrange the front-to-back space all in the same focus, forcing the eye to travel in a straight line. Depends on what you need to say.

DSLRs allow you to elect for the former strategy, while iPhone photography, at least at this point in history, pretty much forces you to adopt the latter. You just don’t have the fine control needed for selective focus in a smartphone, any more than you have a choice shutter speed or how wide you shoot. With few exceptions, the iPhone and its cousins are marvelously adroit point-and-shoots, so your composition options lie chiefly in how you frame things up. Quickly.

This “think fast” mentality works to your benefit in the stealthier parts of street photography. The quicker you click, the harder it is to be detected, which means fewer “hey, what are you doing” issues with reluctant subjects. Even so, you have to be composing consciously if you want to establish a strong line to maximize the illusion of depth. It means deciding where the main drama in a shot resides and composing in reference to it. In the above shot, the woman lost in her John Updike novel is the main interest, but the steep diagonal of the wall leads you to her, then, as a second stage, to the lighter pair of friends in back. Framed in this manner, depth can be accentuated.

There are happy accidents and there are random luck-outs in photography, to be sure, but to create a particular sensation in your pictures, you must craft them. In advance. On purpose.

LOW-TECH LOW LIGHT

Passion Flower, 2015. Budget macro with magnifying diopters ahead of a 35mm lens. 1/50 sec., f/7.1, ISO 100.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LIGHT IS THE PRINCIPAL FUEL OF PHOTOGRAPHY, but it needs refinement, just as crude oil needs to be industrially altered before it’s ready for consumer use. It isn’t just enough to record light in its natural form; it has to be corralled, directed, harnessed so that it enhances a photograph in such a way that, ironically, makes it look like you did nothing at all but press the shutter. So, right at the start, making images is a bit of a con job. Good thing is, it’s only dishonorable when you get caught.

Doing macro on the cheap with the use of screw-on magnifying diopters ahead of your regular lens is one of the situations that can create special lighting challenges. There is an incredibly shallow depth of field in these lenses, but if you compensate for it in the camera, by, say, f/8 or higher, you lose light like crazy. Slow down your shutter to compensate, and you’re on a tripod, since the slightest tremor in a hand-held shot looks like 7.8 on the Richter scale. Keep the shorter shutter speed, though, and you’re jacking ISO up, inviting excessive noise. Flood the shot with constant light, and you might alter the color relationships in a naturally lit object, effecting, well, everything that might appeal in a macro shot.

Best thing is, since you’re shooting such a small object, you don’t need all that much of a fix. In the above shot, for example, the garlic bulb was on a counter about two feet from a window which is pretty softened to start with. That gave me the illumination I needed on the top and back of the bulb, but the side facing me was in nearly complete shadow. I just needed the smallest bit of slight light to retrieve some detail and make the light seem to “wrap” around the bulb.

Cheap fix; half a sheet of blank typing paper from my printer’s feed tray, which was right next door. Camera in right hand, paper in left hand, catching just enough window light to bounce back onto the front of the garlic. A few tries to get the light where I wanted it without any flares. The paper’s flat finish gave me even more softening of the already quiet window light, so the result looked reasonably natural.

Again, in photography, we’re shoving light around all the time, acting as if we just walked into perfect conditions by dumb luck. Yeah, it’s fakery, but, as I say, just don’t get caught.

LEFTOVERS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FAR BE IT FROM ME TO DO A HATER NUMBER on photographic post-processing. We often pretend that the act of photo manipulation began at the dawn of the pixel age, when, of course, people have been futzing with their images since the first shutter snapped. We love the idea of “straight out of the camera” as an ideal, but it’s just that…an ideal. Eventually, it’s the way processing is executed in a specific instance which either justifies or condemns its use.

With that in mind, I do find that too many of us use faux b&w, or the desaturation of color images, long after they’re snapped, as a kind of last-ditch attempt to save pictures that didn’t have enough force or impact in the first place. Have I resorted to this myself? Oh, well, yeah, maybe. Which means, freaking certainly. Have I managed to “save” many images in this way? Not so much. Usually, I feel like I’m serving leftovers and trying to pawn them off as a fresh meal.

Up In Your Grille, 2015. A mere b&w conversion from color would have flattened out many of this image’s tones.

The further along I lope through life, however,the more I tend to believe that the best way to make a black and white image is to set out to intentionally do just that. An act of planning, pre-visualization, deliberation. It means looking at your subject in terms of how a color object will register over the entire tonal range of greys and whites. Also, texture, as it is accentuated by light, is particularly powerful in monochrome, so that part needs to be planned as well. Exposure, as it’s effected by polarizers or colored filters also must be planned, as values in sky, stone or foliage must be anticipated. And, always, there is the use of contrast as drama, something black and white does to great effect.

You might be able to convert a color shot into an even more appealing b&w shot in your kerputer, but the most direct route, that is, making monochrome in the moment, is still the best, since it gives you so many more options while you’re managing every other aspect of the shot in real time. It all comes down to a major philosophical point about photography, which is that the more control you can wield ahead of the click, especially with today’s shoot-it-check-it-shoot-it-again technology, the better your results will be.

SEEING THROUGH THE STORM

At the time of its initial publication in 1893, this image by Alfred Stieglitz was deemed a failure.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LOOK CAREFULLY AT THE PHOTOGRAPH TO YOUR LEFT. It was, at one time, judged by contemporary critics as a grand failure. Alfred Stieglitz, the father of modern photography, and the first to advocate for its status as a legitimate art form, made this image after standing for three hours in the miserable blizzard that had buried the New York of 1893 in mounds of cottony snow.

The coachman and his horses are rendered in a soft haze due to the density of the wind-driven snow, and by the primitive slowness of the photographic plates in use at the time. There was, for photographers, no real option for “freezing the action” (unwitting pun) or rendering the kind of razor sharpness that is now child’s play for the simplest cameras, and so a certain amount of blur was kind of baked into Stieglitz’ project. But look at the dark, moody power of this image! This is a photograph that must live outside the bounds of what we consider “correct”.

More importantly, a technically flawless rendering of this scene would have drained it of half its impact.

Of course, at the time it was created, Stieglitz’ friends encouraged him to throw the “blizzard picture” away. Their simple verdict was that the lack of sharpness had “spoiled” the image. Being imperfect, it was regarded as unworthy. Stieglitz, who would soon edit Camera Work, the world’s first great photographic magazine, and organize the Photo-Secession, America’s first collective of artists for promotion of the photo medium, had already decided that photographs must be more than the mere technical recording of events. They could emphasize drama, create mood, evoke passions, and force the imagination every bit as effectively as did the best paintings.

Within a few years of the making of this image, the members of the Photo-Secession began to tweak and mold their images to actually emulate painting. The movement, called Pictorialism, did not last long, as the young turks of the early 20th century would soon demand an approach to picture-making that matched the modern age. The important thing, however, is that Stieglitz fought for his vision, insisted that there be more than one way to make a picture. That example needs to be followed today more than ever. When you make an image, you must become its champion. This doesn’t mean over-explaining or asking for understanding. It means shooting what you must, honing your craft, and fighting for your vision in the way you bring it to life.

HAPPY OLD YEAR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

The White Rabbit put on his spectacles. ‘Where shall I begin, please your Majesty?’ he asked. ‘Begin at the beginning,’ the King said gravely, ‘and go on till you come to the end: then stop.’

IN A SIMPLER WORLD, THE KING OF HEARTS, quoted above in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, would be perfectly correct. All things being equal, the beginning would be the best place to begin. But, in photography, as in all of life, we are always coming upon a series of beginnings. Learning an art is like making a lap in Monopoly. Just when we think we are approaching our destination, we pass “Go” again, and find that one man’s finish line is another man’s starting gate. Photography is all about re-defining where we are and where we need to be. We always begin, and we never finish.

As 2014 comes to an intersection (I can’t really say ‘a close’ after all that, can I?), it’s normal to review what might be either constant, or changed, about one’s approach to making pictures. That, after all, is the stated aim of this blog, making The Normal Eye more about journey than destination. And so, all I can do in reviewing the last twelve months of opportunities or accidents is to try to identify the areas of photography that most define me at this particular juncture, and to reflect on the work that best represents those areas. This is not to say I’ve gained mastery, but rather that I’m gaining on it. If my legs hold out, I may get there yet. But don’t count on it.

The number twelve has become, then, the structure for the blog page we launch today, called (how does he think of these things?) 12 for 14. You’ll notice it as the newest gallery tab at the top of the screen. There is nothing magical about the number by itself, but I think forcing myself to edit, then edit again, until the thousands of images taken this year are winnowed down to some kind of essence is a useful, if ego-bruising, exercise. I just wanted to have one picture for each facet of photography that I find essentially important, at least in my own work, so twelve it is.

Light painting, landscape, HDR, mobile, natural light, mixed focus, portraiture, abstract composition, all these and others show up as repeating motifs in what I love in others’ images, and what I seek in my own. They are products of both random opportunity and obsessive design, divine accident and carefully executed planning. Some are narrative, others are “absolute” in that they have no formalized storytelling function. In other words, they are a year in the life of just another person who hopes to harness light, perfect his vision, and occasionally snag something magical.

So here we are at the finish line, er, the starting gate, or….well, on to the next picture. Happy New Year.

WATERCOLOR DAYS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE FIRST COLOR PHOTOGRAPHS REALLY…WEREN’T. That is to say, the various recording media, from glass plates to film, were technically incapable of rendering color, leaving entrepreneurial craftsmen (mostly post card artists) to lovingly apply hues with paint and brush. It was the Fred Flintstone version of Photoshop, and, boy howdy, did it sell, regardless of the fact that most flesh tones looked like salmon and most skies looked more eggshell than azure. Until the evolution of a film-based process near the end of the 19th century, these watercolor pastels stood in for the real thing.

Winter’s months-long overcasts and grey days can remind a photographer of what it was like to only be able to capture some of the color in a given subject, as the change in light washes the brilliance out of the world, leaving it like a faded t-shirt and creating the impression that color, as well as botany, goes into the hibernational tomb during winter.

Of course, we can boost the hues in the aftermath just like those patient touch-up artists of the 1800’s, but in fact there are things to be learned from rendering tones on the soft pedal. In fact, reduced color is a kind of alternate reality. Capturing it as it actually appears, rather than amping it up to neon rudeness, can actually be a gentle shaper of mood.

Light that seeps through cloud cover is diffused, and shadows, if they survive at all, are faint and soft. The look is really reminiscent of early impressionism, and, when matched up with the correct subject matter, can complement a scene in a way that a more garish spectrum would only ruin.

Just like volume in music, color in photography is meant to speak at different decibel levels depending on the messaging at hand. Winter is a wonderful way to force ourselves to work out of a distinctly different paint box.

STEALTH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AT A PARTY, THERE ARE DISTINCT ADVANTAGES TO NOT BEING AN “OFFICIAL” PHOTOGRAPHER. You could probably catalogue many of them yourself with no strain. Chief among the perks of being an amateur (can we get a better word for this?) is that you are the captain of your own fate. You shoot what you want, when you want. Your arrival on the scene is not telegraphed by stacks of accompanying cases, light fixtures, connecting cords or other spontaneity killers that are essential to someone who has been “assigned” to an event. Your very unimportance is your license to fly, your ticket to liberation. Termed honestly (if unkindly), your work just doesn’t matter to anyone else, and so it can mean everything to you. Yay.

One of the supreme kicks I derive from going to events with my wife is that I can make her forget I’m there. I mean, as a guy with a camera. She has the gift of being able to submerge completely into the social dynamics of wherever she is, so she is not thinking about when I may elect to sneak up and snap her. Believe me, when you live with a beautiful woman who also hates to have her picture taken, this is like hitting the trifecta at Del Mar. At 20 to 1.

Free from the constraints of being “on the job”, I enjoy a kind of invisibility at parties, since I use the fastest lenses I can and no flash, ever, ever, ever. I do not call attention to myself. I do not exhort people to smile or arrange them next to people that they may or may not be able to stand. The word “cheese” never leaves my lips. I take what the moment gives me, as that is often richer than anything I might concoct, anyway. Working with a DSLR is a little more conspicuous than the magical invisibility of a phone camera, which people totally ignore, but if I am cagey, I can work with an “official” camera and not be perceived as a threat. Again, with a woman who (a) looks great and (b) doesn’t like how she looks in pictures, this is nirvana.

Candid photography is all about the stealth. It’s not about warning or prepping people that, attention K-Mart shoppers, you’re about to have your picture took. The more you insert yourself into the process (look over here! big smiiiiile!) the more you interrupt the natural rhythm that you set out to capture. So stop working against yourself. Be a happy sneak thief. Like me.

PRESERVING THE PERCEPTION

Your memory tells you that this space is more like a “library” than a “drug store”, unless you live in a much nicer neighborhood than mine.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS AN OLD ADVERTISING MAXIM that the first person to introduce a product to market becomes the “face” of all versions of that product forever, no matter who else enters as a competitor. Under this thinking, all soda generically becomes a Coke; all facial tissues are Kleenexes: and no matter who made your office copier, you use it to make…Xeroxes. The first way we encounter something often becomes the way we “see” it, maybe forever.

Photography is shorthand for what takes much longer to explain verbally, and sometimes the first way we visually present something “sticks” in our head, becoming the default image that “means” that thing. Architecture seems to send that signal with certain businesses, certainly. When I give you Doric columns and gargoyles, you are a lot likelier to think courthouse than doghouse. If I show you panes of reflective glass, large open spaces and stark light fixtures, you might sift through your memory for art gallery sooner than you would for hardware store. It’s just the mind’s convenient filing system for quickly identifying previous files, and it can be a great tool for your photography as well.

As a shooter, you can sell the idea of a type of space based on what your viewer expects it to look like, and that could mean that you shoot an understated or even tightly composed, partial view of it, secure in the knowledge that people’s collective memory will provide any missing data. Being sensitive to what the universally accepted icons of a thing are means you can abbreviate or abstract its presentation without worrying about losing impact.

Photography can be at its most effective when you can say more and more with less and less. You just have to know how much to pare away and still preserve the perception.

QUICK, NOBODY POSE

Even at the Los Angeles Zoo, the most interesting animals are on the opposite side of the bars. 1/80 sec., f/4, ISO 200, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR PHOTOGRAPHERS, HARNESSING THE NATURAL ENERGY OF A CHILD is a little like flying a kite during a thunderstorm was for Ben Franklin. You might tap into a miraculous force of nature, but what are you going to do with it? Of course, there’s big money in artificially arranging light and props for formalized (or rather, idealized) portraits of kids. It’s a specialty art with specific rules and systems, and for proud parents, it’s a steady market. We all want our urchins “promoted” to angel status, albeit briefly. However, in terms of photographic gold, you can’t, for my money, beat the controlled chaos of children at play. It’s street photography with an overlay of comedy and wonder.

However, attempting to extract a miracle while watching kids be kids is like trying to capture either sports or combat, in that it has a completely different dynamic from second to second, so much so that you should be prepared to shoot a lot, shifting your focus and framing on the fly, since the center of the action will shift rapidly. I don’t necessarily believe that there is one decisive moment which will explain all aspects of childhood since the creation of the world, but I do think that some moments have a better balance between sizes, shapes, and story elements than others, although you will be shooting instinctively for much of the time, separating the wheat from the chaff later upon review of the results.

As with the aforementioned combat and sports categories, the spirit that is caught in a shot supersedes technical perfection. I’m not saying you should throw sharpness or composition to the wind, but I think the immediacy of some images trumps the controlled environment of the studio or a formal sitting. Some artifacts of blur, inconsistent lighting, or imprecise composition can be overlooked if the overall effect of the shot is truthful, visceral. The very nature of candid photography renders all arbitrary rules rather useless. The results justify themselves regardless of their raggedness, whereas a technically flawless shot that is also bloodless can never be justified on any grounds.

Work the moment; trust it to develop naturally; hitch a ride on the wave of the instantaneous.

FIVE-DECKER SANDWICH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MY PHOTOGRAPHY IS OCCASIONALLY AKIN TO MY GRANDMOTHER’S COOKING METHOD, which produced culinary miracles without a trace of written recipes or cookbooks. Her approach was completely additive; she merely kept throwing things into the pot until it looked “about right”. I was aware of the difference, in her hands, between portions that were labeled “smidges”, “tastes”, “pinches” and even “tads” (as in, “this is a tad too bitter. Give me the salt.) I never questioned her results: I merely scarfed them down and eagerly asked for seconds.

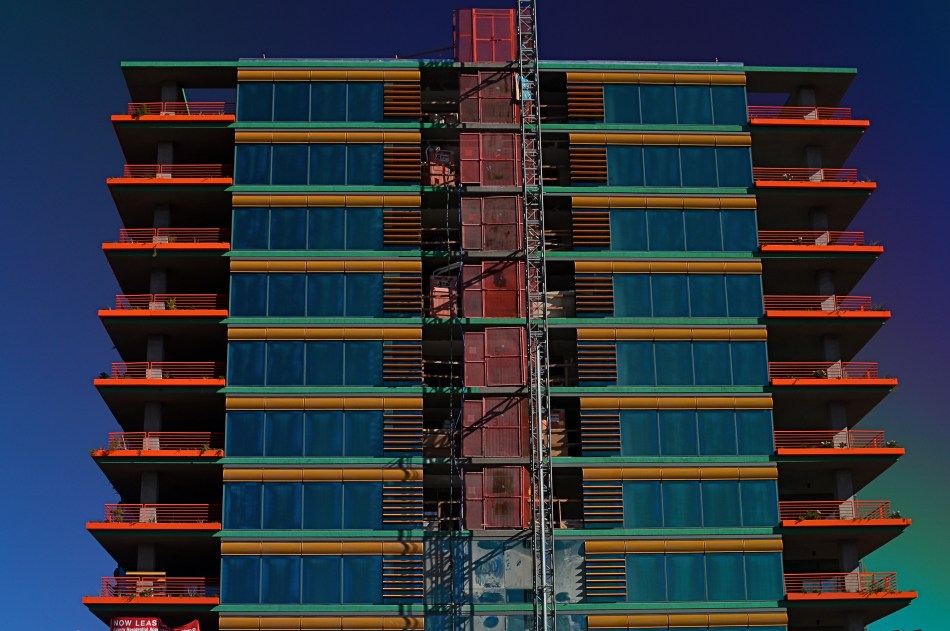

Picture making can also be a matter of adding enough pinches and tads to create just the right mix of factors for the image you need. It’s frequently as instinctual a process as Gram’s, but sometimes you have to analyze what worked by thinking the shot backwards after the fact. In the case of the above image, what you see, although it was shot very quickly, is actually the convergence of several different ingredients, the combination of which would be all wrong for some photos, but which actually served this subject fairly well.

The five-decker sandwich of factors in the shot begins with the building, which is quite intense in color all by itself, yet not quite contrasty enough to suit me in this specific instance. So let’s see all the hoops the camera had to jump through to get this particular image:

First, it was taken during the so-called “golden hour”, just before sunset, in late fall in Arizona. That guarantees at least one boost of the building’s native intensity. The next factor is the camera’s own color settings, which are set to “vibrant.” Level three comes from a polarizing filter, which is juicing the sky from its hazy southwestern “normal” to a deep blue. For the fourth element, I am also adding a second filtering component by shooting through a heavily tinted car window (there’s no other kind in Arizona), which presents here as the gradation of sky from blue at the top of the frame to a near aqua near the bottom. And finally, I am way under-exposing the shot at 1/320, deepening the colors yet one more time.

The fun of this is that it all happens ahead of the click, and keeps your fingers off the Photoshop trigger. Grandma may not have spent any more time laboring over a photo than a quick snap of a box Brownie, but she knew how to take stew meat and morph it into filet. And, as with the making of a picture, you just keep adding stuff until the mixture in the pot looks “about right.”

PUBLIC INTIMACY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

OKAY, I JUST REALIZED HOW GROSSLY MISLEADING THE TITLE OF THIS POST COULD SEEM, but, trust me, I never meant it the way it sounds. I was just struggling to find a phrase for the kind of photograph in which a person is as private as possible while on full display to the world at large. There are behaviors that are intensely personal and astonishingly public at the same time, and such events in a human being’s life are rife, for the photographer, with a very singular kind of drama.

We like to think of ourselves as sufficiently camouflaged behind the carefully crafted mask that we present for the public’s consumption, all the better to preserve our sense of privacy. But there are always cracks in the mask, fleeting signals at the raw life underneath. Learning to detect those cracks is the talent of the street photographer, whose eye is always trained beyond the obvious.

Mourning, Joy, Discovery…all these things provide a teeter-totter balance between public display and private truth. The primal basics of life bring that juggling act into view, and, as a photographer, I am often surprised how much of them is in evidence in the simple act of nourishing ourselves. Dining would seem, on the surface, to be all about simple survival. Eating to live, and all that. But meals are laden with ritual and habit, the most hard-wired parts of one’s personality. Food gathers people for so much more than mere sustenance. It is memory, community, religion, friendship, negotiation, reassurance, replenishment. It is a symbol for life (and its passing), a trigger for shared experience, a talisman, a consecration.

Case in point: the man and woman in the above image were seen in a Los Angeles restaurant late on a Saturday night. Their relationship would seem to be that of mother and son, but it could be grandmother and nephew, son-in-law and mother-in-law, or a dozen other arrangements. A sharp contrast is provided by their comparative ages and physicality. One sits upright, while the other sits as well as she can. There is no eye contact….but does that necessarily mean that they do not want to see each other? There is no conversation. Has everything already been said? Are they grateful to still be there for each other after all these years, or is this the fulfillment of an obligation, a visitation occasioned by guilt?

Eating is a microcosmic examination of everything that it means to be human. So much for a single photographic frame to try to capture. So many ways of looking into the publicness of privacy.

FADE TO (ALMOST) BLACK

Sometimes a change in the technical approach to a shot is the only way to freshen an old subject. 1/40 sec., f/1.8, ISO 250, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I KNOW MANY PHOTOGRAPHERS WHO SUBJECT THEMSELVES TO THE DELICIOUS TORTURE, known to authors everywhere,as “publish or perish”, or, in visual terms, the tyranny of shooting something every single day of their lives. There are lots of theories afloat as to whether this artificially imposed discipline speeds one’s development, or somehow pumps their imagination into the bulky heft of an overworked bicep. You must decide, o seekers of truth, what merit any of this has. I myself have tried to maintain this kind of terrifying homework assignment, and during some periods I actually manage it, for a while at least. But there are roadblocks, and one of the chief barriers to doing shot-a-day photography is subject matter, or rather the lack of it.

Let’s face it: even if you live one canyon away from the most breathtaking view on earth or walk the streets of the mightiest metropolis, you will occasionally look upon your immediate environs as a bad rerun of Gilligan’s Island, something you just can’t bear to look at without having a wastebasket handy. Familiarity breeds contempt for some subjects that you’ve visited and re-visited, and so, for me, the only way to re-mix old material is to re-imagine my technical approach to it. This is still a poor substitute for a truly fresh challenge, but it can teach you a lot about interpretation, which has transformed more than a few mundane subjects for me over a lifetime of shuttering (and shuddering).

As an example, a corner of my living room has been one of the most trampled-over crime scenes of my photographic life. The louvered shades which flank my piano can create, over the course of a day, almost any kind of light, allowing me to use the space for quick table-top macros, abstract arrangements of shadows, or still lifes of furnishings. And yet, on rainy /boring days, I still turn to this corner of the house to try something new with the admittedly over-worked material. Lately I have under-exposed compositions in black and white, coming as near a total blackout as I can to try to reduce any objects to fundamental arrangements of light and shadow. In fact, damn near the entire frame is shadow, something which works better in monochrome. Color simply prettifies things too much, inviting the wrong kind of distracted eye wandering in areas of the shot that I don’t think of as essential.

I crank the aperture wide open (or nearly) to keep a narrow depth of field, which renders most of the image pretty soft. I pinch down the window light until there is almost no illumination on anything, and allow the ISO to float around at least 250. I get a filmic, grainy, gauzy look which is really just shapes and light. It’s very minimalistic, but it allows me to milk something fresh out of objects that I’ve really over-photographed. If you believe that context is everything, then taking a new technical approach to an old subject can, in fact, create new context. Fading almost to black is one thing to try when you’re stuck in the house on a rainy day.

Especially if there’s nothing on TV except Gilligan.

ON THE SOFT SIDE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE WORLD’S FIRST MOVIE STUDIO WAS A TARPAPER SHACK ON A TURNTABLE. Dubbed by Thomas Edison’s techies as “The Black Maria” (as ambulances were grimly named back at the time), the structure rotated to take advantage of wherever sunlight was available in the California sky, thus allowing the film crew to extend its daily shooting schedule by more than half in the era of extremely slow film stocks. Eventually artificial light of sufficient strength was developed for the movies, and actors no longer had to brave motion sickness just to rescue fair damsels. So it goes.

More than a century hence, some photographers actually have to be reminded to use natural light, specifically window light, as a better alternative to studio lights or flash units. Certainly anyone who has shot portraits for a while has already learned that window light is softer and more diffuse than anything you can plug in, thus making it far more flattering to faces (as well as forgiving of , er, flaws). It’s also good to remember that it can lend a warming effect to an entire room, on those occasions where the room itself is a kind of still life subject.

Your window light source can be harsher if the sun is arching over the roof of your building toward the window (east to west), so a window that receives light at a right angle from the crossing sun is better, since it’s already been buffered a bit. This also allows you to expose so that the details outside the window (trees, scenery, etc.) aren’t blown out, assuming that you want them to be prominent in the picture. For inside the window, set your initial exposure for the brightest objects inside the room. If they aren’t white-hot, there is less severe contrast between light and dark objects, and the shot looks more balanced.

I like a look that suggests that just enough light has crept into the room to gently illuminate everything in it from front to back. You’ll have to arrive at your own preferred look, deciding how much, if any, of the light you want to “drop off” to drape selective parts of the frame in shadow. Your vision, your choice. Point is, natural light is so wonderfully workable for a variety of looks that, once you start to develop your use of it, you might reach for artificial light less and less.

Turns out, that Edison guy was pretty clever.

THE BOY IN THE BALL CAP

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MORE SHOTS, MORE CHOICES: Photography really is as simple as that. The point has been hammered home by expert and amateur alike since before we could say “Kodak moment”: over-shooting, snapping more coverage from more vantage points, results in a wider ranger of results, which, editorially, can lead to finding that one bit of micro-mood, that miraculous mixture of factors that really does nail the assignment. Editors traditionally know this, and send staffers out to shoot 120 exposures to get four that are worthy of publication. It really, ofttimes, is a numbers game.

For those of us down here in the foot soldier ranks, it’s rare to see instances of creative over-shoot. We step up to the mountain or monument, and wham, bam, there’s your picture. We tend to shoot visual souvenirs: see, I was there, too. Fortunately, one of the times we do shoot dozens upon dozens of frames is in the chronicling of our families, especially the day-to-day development of our children. And that’s vital, since, unlike the unchanging national monument we record on holiday, a child’s face, especially in its earlier years, is a very dynamic subject, revealing vastly different features literally from frame to frame. As a result, we are left with a greater selection of editing choices after those faces dissolve into other faces, after which they are gone in a thrilling and heartbreaking way.

One humbling thing about shooting kids is that, after they have been around a while, you realize that you might have caught something essential, months or years ago, during an event at which you just felt like you were reacting, racing to catch your quarry, get him/her in focus, etc. A feeling of always trying to catch up. It’s one of the only times in our own lives that we shoot like paparazzi. This might be something, better get it. I’ll sort it out later. The process is so frenetic that some images may only reveal their gold several miles down the road.

Not the sharpest image I ever shot, but look at that face. Slow shutter to compensate for the dim light. 1/40 sec., f/3.2, ISO 200, 35mm.

My grandson is now entering kindergarten. He’s reading. He’s a compact miniature of his eventual, total self. And, in recently riffing through images of him from early five years ago (and yes, I was sniffling), I found an image where he literally previews the person I now know him to be. This image was always one of my favorite pictures of him, but it is more so now. In it, I see his studious, serious nature, and his intense focus, along with his divine vulnerability and innocence. Technically, the shot is far from perfect, as I was both racing around to catch him during one of his impulse-driven adventures and trying to master a very new lens. As a result, his face is a little soft here, but I don’t know if that’s so bad, now that I view it with new eyes. The light in the room was itself pretty anemic, leaking through a window from a dim day, and running wide open on a 50mm f/1.8 lens at a slow 1/40 was the only way I was going to get anything without flash, so I risked misreading the shallow depth of field, which I kinda did. However, I’ll take this face over the other shots I took that day. Whatever I was lacking as a photographer, Henry more than compensated for as a subject.

Final box score: the boy in the ball cap hit it out of the park.

Thanks, Hank.

PENCIL VS. INK

This iPhone capture is more of a preliminary sketch than a final rendering, since the camera adds too much noise in low light. I’ll return with a Nikon to get this “right”.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

RAISED AS THE SON OF AN ILLUSTRATOR WHO WAS ALSO A PHOTOGRAPHER, I have always been more comfortable with the idea of the photographic image as a work-in-progress rather than as a finished thing. That is, I bring a graphic artist’s approach to any project I do, which is to visualize an idea several different ways before committing myself to the final rendering. Call if sketching, roughing, rehearsing…..whatever…but, both on the page/canvas and the photograph, I see things taking shape over the space of many trial “drafts”. And, just as you don’t just step up and draw a definitive picture, you usually can’t just step up and snap a fully realized photo. I was taught to value process over product, or, if you will, journey over destination.

This belief was embodied in my dad’s advice to lay down as many pencil lines as possible before laying in the ink line. Ink meant commitment. We’re done developing. We’re finished experimenting. Ready to push the button and, for better or worse, live with this thing. Therefore the idea of a sketch pad, or preliminary studies of a subject, eventually led to a refined, official edition. This seems consistent with people like Ansel Adams, who re-imagined some of his negatives more than half a dozen times over decades, each print bearing its own special traits, even though his source material was always the same. Similarly, “studies” in music served as miniature versions of themes later realized in full in symphonies or concertos.

The photo equivalent of a sketch pad, for me in 2014, is the phone camera. It’s easy to carry everywhere, fairly clandestine, and able to generate at least usable images under most conditions. This allows me to quickly knock off a few tries on something that, in some cases, I will later shoot “for real” (or “for good”) with a DSLR, allowing me to use both tools to their respective strengths. The spy-eye-I-can-go-anywhere aspect of iPhones is undeniably convenient, but often as not I have to reject the images I get because, at this point in time, it’s just not possible to exert enough creative control over these cameras to give full voice to everything in my mind. If the phone camera is my sketch pad, my full-function camera is my ink and brush. One conceives, while the other refines and commits.

You write things like this knowing full well that technology will make a monkey out of you at its next possible opportunity, and I actually look forward to the day when I am free of the bulk and baggage of what are, at least now, better cameras overall. But we’re not there yet, and may not be for a while. I still make the distinction between a convenient camera and a “real” camera, and I freely admit that bias. A Porsche is still better than a bicycle, and the first time you’re booked as a pianist into Carnegie Hall, your manager doesn’t insist that they provide you with a state-of-the-art….Casio. It’s a Steinway or the highway.

RAMPING UP

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN THE IMAGINARY PHOTOGRAPHY BOOKSHELF OF MY MIND THERE ARE HUNDREDS OF VOLUMES that speak of nothing else except the exquisite light of early morning, the so-called “golden hour” in which a certain rich warmth bathes all. You’ve read endless articles and posts on this as well, so nothing I can cite about the science or aesthetic aspects of it can add much. However, I think that there is a secondary benefit to shooting early in the day, and it speaks to human rhythm, a factor which creates opportunities for imaging every bit as vital as the quality of available light.

Cities and communities don’t jolt awake in one surge: they gently creep into life, with streets gradually taking on the staging that will define that day. The first signs could be the winking on of lights, or the slow, quiet shuffle of the first shift of cleaners, washers, trimmers and delivery workers. First light brings the photographer a special relationship with the world, as he/she has a very private audience with all the gears that will soon whirr and buzz into the overall noise of the day. You are witness to a different heartbeat of life, and the quieter pace informs your shooting choices, seeping into you in small increments like a light morning dew. You are almost literally forced to move slower, to think more deliberately, and that state always makes for better picture making.

Some atmospheres, like libraries or churches, retain this feel throughout the entire day, imposing a mood of silence (or at least contemplation) that is also conducive to a better thought process for photography, but in most settings, as the day wears on, the magic wears off. Early day is a distinctly different day from the one you’ll experience after 9am. It isn’t merely about light, and, once you learn to re-tune your inner radio for it, you can find yourself going back for more.

This is no mere poetic dreaminess. The more nuances you experience as a living, breathing human, the more you have to pour into your photography. Live fuller and you’ll shoot better. That’s why learning about technical things is no guarantee that you’ll ever do anything with a camera beyond a certain clinical “okay-ness”. On the other hand, we see dreamers who are a solid C+ on the tech stuff deliver A++ images because their soul is part of the workflow.