THE MOST FROM THE LEAST

Reaching a comfort zone with your equipment means fewer barriers between you and the picture you want to get. 1/80 sec., f/4.5, ISO 100, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY IS ONLY PARTLY ABOUT TAKING AND VIEWING IMAGES. Truly, one of the most instructive (and humbling) elements of becoming a photographer is listening to the recitation of other photographers’ sins, something for which the internet era is particularly well suited. The web will deliver as many confessions, sermons, warnings and Monday-morning quarterbacks as you can gobble at a sitting, and, for some reason, these tales of creative woe resonate more strongly with me than tales of success. I like to read a good “how I did it” tutorial on a great picture, but I love, love, love to read a lurid “how I totally blew it” post-mortem. Gives me hope that I’m not the only lame-o lumbering around in the darkness.

One of the richest gold fields of confession for shooters are entries about how they got seduced into buying mounds of photographic toys in the hope that the next bit of gear would be the decisive moment that insured greatness. We have all (sing it with me, brothers and sisters!) succumbed to the lure of the lens, the attachment, the bracket, the golden Willy Wonka ticket that would transform us overnight from hack to hero. It might have been the shiny logo on the Nikon. It might have been the seductive curve on the flash unit. Whatever the particular Apple to our private Eden was, we believed it belonged in our kit bags, no less than plasma in a medic’s satchel. And, all too often, it turned out to be about as valuable as water wings on a whale. He who dies with the most toys probably has perished from exhaustion from having to haul them all around from shot to shot, feeding the aftermarket’s bottom line instead of nourishing his art.

My favorite photographers have always been those who have delivered the most from the least: street poet Henri Cartier-Bresson with his simple Leica, news hound Weegee with his Speed Graphic perpetually locked to f/16 and a shutter speed of 1/200. Of course, shooters who use only essential equipment are going to appeal to my working-class bias, since peeling off the green for a treasure house of toys was never in the cards for me, anyway. If I had been the youthful ward of Bruce Wayne, perhaps I would have viewed the whole thing differently, but we are who we are.

I truly believe that the more equipment you have to master, the less possible true mastery of any one part of that mound of gizmos becomes. And as I grow gray, I seem to be trying to do even more and more with less and less. I’m not quite to the point of out-and-out minimalism, but I do proceed under the principle that the feel of the shot outranks every other technical consideration, and some dark patches or soft edges can be sacrificed if my eye’s heart was in the right place.

Of course, I haven’t checked the mail today. The new B&H catalogue might be in there, in which case, cancel my appointments for the rest of the week.

Sigh.

ON THE NOSE (AND OFF)

I had originally shot the organ loft at Columbus, Ohio’s St. Joseph Cathedral in a centered, “straight on” composition. I like this variation a little better. 1/40 sec., f/3.5, ISO 1000, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AMONG THE GROUPS INVITING FLICKR USERS TO POST PHOTOGRAPHS OF A CERTAIN THEME OR TYPE, there is a group called, “This Should Be A Postcard”, apparently composed of images that are so iconically average that they resemble mass-produced tourist views of scenic locales. The name of this group puzzles me. I mean, if you called it, “Perfectly Ordinary, Non-Offensive and Safe Pictures of Over-Visited Places”, people would write you off as a troll, but I’d at least give you points for accuracy. It’s hard to understand why any art would aspire to look like something that is almost deliberately artless.

And still, it is perceived as a compliment to one’s work to be told that it “looks just like a postcard”, and, I swear, when I hear that remark about one of my own images, my first reaction is to wipe said image from the face of the earth, since that phrase means that it is (a)average, (b) unambitious), (c) unimaginative, or (d) a mere act of “recording”. Look, here’s the famous place. It looks just like you expect it to, taken from the angle that you’re accustomed to, lit, composed and executed according to a pre-existing conception of what it’s “supposed” to be. How nice.

And how unlike anything photography is supposed to be about.

This conditioning we all have to render the “official” view of well-known subjects can only lead to mediocrity and risk aversion. After all, a postcard is tasteful, perfect, symmetrical, orderly. And eventually, dull. Thankfully, the infusion of millions of new photographers into the mainstream in recent years holds the potential cure for this bent. The young will simply not hold the same things (or ways to view them) in any particular awe, and so they won’t even want to create a postcard, or anyone else’s version of one. They will shudder at the very thought of being “on the nose”.

I rail against the postcard because, over a lifetime, I have so shamelessly aspired to it, and have only been able to let go of the fantasy after becoming disappointed with myself, then unwilling to keep recycling the same approach to subject matter even one more time. For me, it was a way of gradually growing past the really formalized methods I had as a child. And it’s not magic.Even a slight variation in approach to “big” subjects, as in the above image, can stamp at least a part of yourself onto the results, and so, it’s a good thing to get the official shot out of the way early on in a shoot, then try every other approach you can think of. Chances are, your keeper will be in one of the non-traditional approaches.

Postcards say of a location, wish you were here. Photographs, made by you personally, point to your mind and say, “consider being here.”

FIGHTING TO FORGET

By MICHAEL PERKINS

STORIES OF “THE LAND THAT TIME FORGOT” COMPRISE ONE OF THE MOST RELIABLE TROPES IN ALL OF FICTION. The romantic notion of stumbling upon places that have been sequestered away from the mad forward crunch of “progress” is flat-out irresistible, since it holds out the hope that we can re-connect with things we have lost, from perspective to innocence. It moves units at the book store. It sells tickets at the box office. And it provides photographers with their most delicate treasures.

Whether our lost land is a village in some hidden valley or a hamlet within the vast prairie of middle America, we romanticize the idea that some places can be frozen in amber, protected from us and all that we create. Sadly, finding places that have been allowed to remain at the margins, that have been left alone by developers and magnates, is getting to be a greater rarity than ever before. Small towns can be wholly separate universes, sealed off from the silliness that has engulfed most of us, but just finding one which has been lucky enough to aspire to “forgotten” status is increasingly rare.

That’s why it’s so wonderful when you take the wrong road, and make the right turn.

The above stretch of sunlit houses, parallel to their tiny town’s main railroad spur, shows, in miniature, a place where order is simple but unwavering. Colors are basic. Lines are straight. This is a town where school board meetings are still held at the local Carnegie library, where the town’s single diner’s customers are on a first name basis with each other. A place where the flag is taken down and folded each night outside the courthouse. A village that wears its age like an elder’s furrowed brow with quietude, serenity.

There are plenty of malls, chain burger joints, car dealerships and business plazas within several miles of here. But they are not of here. They keep their distance and mind their manners. The freeway won’t be barreling through here anytime soon. There’s time yet.

Time for one more picture, as simple as I know how to make it.

A memento of a world fighting to forget.

THE LITTLE WALLS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

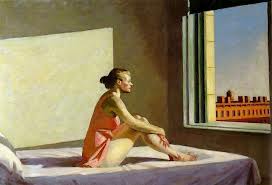

THE PAINTER EDWARD HOPPER, ONE OF THE GREATEST CHRONICLERS OF THE ALIENATION OF MAN FROM HIS ENVIRONMENT, would have made an amazing street photographer. That he captured the essential loneliness of modern life with invented or arranged scenes makes his pictures no less real than if he had happened upon them naturally, armed with a camera. In fact, his work has been a stronger influence on my approach to making images of people than many actual photographers.

“Maybe I am not very human”, Hopper remarked, “what I wanted to do was to paint sunlight on the side of a house.” Indeed, many of his canvasses fairly glow with eerily golden colors, but, meanwhile, the interiors within which his actors reside could be defined by deep shadows, stark furnishings, and lost individuals who gaze out of windows at….what? The cities in his paintings are wide open, but his subjects invariably seem like prisoners. They are sealed in, sequestered away from each other, locked by little walls apart from every other little wall.

I occasionally see arrangements of people that suggest Hopper’s world to me. Recently, I was spending the day at an art museum which features a large food court. The area is open, breathable, inviting, and nothing like the group of people in the above image. For some reason, in this place, at this moment, this distinct group of people appear as a complete universe unto themselves, separate from the whole rest of humanity, related to each other not because they know each other but because they are such absolute strangers to each other, and maybe to themselves. I don’t understand why their world drew my eye. I only knew that I could not resist making a picture of this world, and I hoped I could transmit something of what I was seeing and feeling.

I don’t know if I got there, but it was a journey worth taking. I started out, like Hopper, merely chasing the light, but lingered, to try to articulate something very different.

Or as Hopper himself said, “It you could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint”.

THE MAIN POINT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MAKING PICTURES, FOR ME, IS LIKE MAKING TAFFY. The only good results I get are from stretching and twisting between two extremes. Push and pull. Yank and compress. Stray and stay. Say everything or speak one single word.

This is all about composition, the editing function of what to put in or leave out. In my head, it’s a constant and perpetually churning debate over what finally resides within the frame. No, that needs something more. No, that’s way too much. Cut it. Add it. I love it, it’s complete chaos. I love it, it’s stark and lonely.

Can’t settle the matter, and maybe that’s the point. How can your eye always do the same kind of seeing? How can your heart or mind ever be satisfied with one type of poem or story? Just can’t, that’s all.

But I do have a kind of mental default setting I return to, to keep my tiny little squirrel brain from exploding.

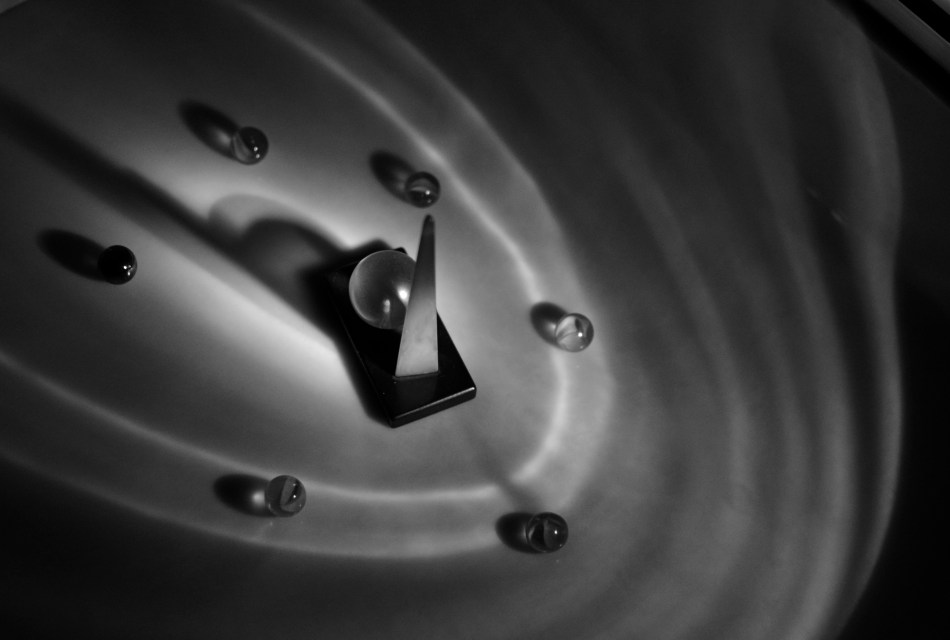

When I need to clean out the pipes, I tend to gravitate to the simplest compositions imaginable, a back-to-basics approach that forces me to see things with the fewest possible elements, then to begin layering little extras back in, hoping I’ll know when to stop. In the case of the above image, I was shooting inside a darkened room with only an old 1939 World’s Fair paperweight for a subject, and holding an ordinary cheap flashlight overhead with one hand as I framed and focused, handheld, with the other hand. I didn’t know what I wanted. It was a fishing expedition, plain and simple. What I soon decided, however, was that, instead of one element, I was actually working with two.

Basic flashlights have no diffusers, and so they project harsh concentric circles as a pattern. Shifting the position of the flashlight seemed to make the paperweight appear to be ringed by eddying waves, orbit trails if you will. Suddenly the mission had changed. I now had something I could use as the center of a little solar system, so, now,for a third element, I needed “satellites” for that realm. Back to the junk drawer for a few cat’s eye marbles. What, you don’t have a bag of marbles in the same drawer with your shaving razor and toothpaste? What kinda weirdo are you?

Shifting the position of the marbles to suggest eccentric orbits, and tilting the light to create the most dramatic shadow ellipses possible gave me what I was looking for….a strange, dreamlike little tabletop galaxy. Snap and done.

Sometimes going back to a place where there are no destinations and no rules help me refocus my eye. Or provides me with the delusion that I’m in charge of some kind of process.

THE ENNOBLING GOLD

Brooklyn Block, 2014. No, this building isn’t this pretty in “reality”. And that’s the entire point. 1/100 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LIGHT IS THE ULTIMATE MAKE-UP ARTIST, the cosmetic balm that paints warmth, softness, even a kind of forgiveness, or dignity onto the world. Photographers use light in a different way than painters, since a canvas, beginning as a complete blank, allows the dauber to create any kind of light scheme he desires. It’s a very God-like, “let there be light” position the painter finds himself in, whereas the photographer is more or less at light’s mercy, if you will. He has to channel, harness, or manage whatever the situation has provided him with, to wrangle light into an acceptable balance.

No complaints about this, by the way. There’s nothing passive about this process: real decisions are being made, and both painters and photographers are judged by how they temper and combine all the elements they use in their assembly processes. Just because a shooter works with light as he finds it, rather than brushing it into being, doesn’t make him/her any less in charge of the result. It’s just a different way to get there.

Light always has the power to transform objects into, if you will, better versions of themselves. I call it the “ennobling gold”, since I find that the yellow range of light is kindest to a wider range of subjects. Stone or brick, urban crush or rural hush, light produces a calming, charming effect on nearly anything, which is what makes managing light so irresistible to the photographer. He just knows that there is beauty to be extracted when the light is kind. And he can’t wait to grab all he can.

“Light makes photography”, George Eastman famously wrote. “Light makes photography. Embrace light. Admire it. Love it. But, above all, know light. Know it for all you are worth, and you will know the key to photography.”

Yeah, what he said.

STUPIDLY WISE

Blendon Woods, Columbus, Ohio, 1966. I usually had to shoot an entire roll of film to even come this close to making a useable shot.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IGNORANCE, IN PHOTOGRAPHY, CERTAINLY IS NOT BLISS. However, exposure to that selfsame know-nothing-ness can lead to a kind of bliss, since it can eventually lead you to excellence, or at least improvement. Here and now, I am going to tell you that all the photographic tutorials and classes in history cannot teach you one millionth as much as your own rotten pictures. Period.

Trick is, you have to keep your misbegotten photographic children, and keep them close. Love them. Treasure the hidden reservoir of warnings and no-nos they contain and mine that treasure for all it’s worth. Of course, doing this takes real courage, since your first human instinct, understandingly, will be to do a Norman Bates on them: stab them to death in the shower and bury their car in the swamp out back.

But don’t.

I have purposely kept the results of the first five rolls of film I ever shot for over forty years now. They are almost all miserable failures, and I mean that with no aw-shucks false modesty whatever. I am not exaggerating when I tell you that these images are the Fort Knox of ignorance, an ignorance taller than most minor mountain ranges, an ignorance that, if it was used like some garbage to create energy, could light Europe for a year. We’re talking lousy.

But mine was a divine kind of ignorance. At the age of fourteen, I not only knew nothing, I could not even guess at how much nothing I knew. It’s obvious, as you troll through these Kodak-yellow boxes of Ektachrome slides, that I knew nothing of the limits of film, or exposure, or my own cave-dweller-level camera. Indeed, I remember being completely mystified when I got my first look at my slides as they returned from the processor (an agonizing wait of about three days back then), only to find, time after time, that nothing of what I had seen in my mind had made it into the final image. It wasn’t that dark! It wasn’t that color! It wasn’t…..working. And it wasn’t a question of, “what was I thinking?”, since I always had a clear vision of what I thought the picture should be. It was more like, “why didn’t that work?“, which, at that stage of my development, was as easy to answer as, say, “why don’t I have a Batmobile?” or “why can’t I make food out of peat moss?”

Different woods, different life. But you can’t get here without all the mistakes it builds on. 1/400 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

But holding onto the slides over the years paid off. I gradually learned enough to match up Lousy Slide “A” with Solution”B”, as I learned what to ask of myself and a camera, how to make the box do my bidding, how to build on the foundation of all that failure. And the best thing about keeping all of the fizzles in those old cartons was that I also kept the few slides that actually worked, in spite of a fixed-focus, plastic lens, light-leaky box camera and my own glorious stupidity. Because, since I didn’t know what I could do, I tried everything, and, on a few miraculous occasions, I either guessed right, or God was celebrating Throw A Mortal A Bone Day.

Thing is, I was reaching beyond what I knew, what I could hope to accomplish. Out of that sheer zeal, you can eventually learn to make photographs. But you have to keep growing beyond your cameras. It’s easy when it’s a plastic hunk of garbage, not so easy later on. But you have to keep calling on that nervy, ignorant fourteen-year-old, and giving him the steering wheel. It’s the only way things get better.

You can’t learn from your mistakes until you room with them for a semester or two. And then they can teach you better than anyone or anything you will ever encounter, anywhere.

SUBMERGED IN BEING

Cropped and enhanced from a group shot. I could sit this young woman in a studio for a thousand years and not get this expression.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CANDID PORTRAITURE IS VOLATILE, THE DEAD OPPOSITE OF A FORMAL SITTING, and therefore a little scarier for some photographers. We tell ourselves that we gain more control over the results of a staged portrait, since we are dictating so many terms within it…the setting, the light, the choice of props, etc. However, can’t all that control also drain the life out of our subjects by injecting self-consciousness ? Why do you think there are so many tutorials written about how to put your subjects at ease, encourage them to be themselves, persuade them to unclench their teeth? Getting someone to sit where we tell them, do what we tell them, and yet “act naturally” involves a skill set that many photographers must learn over time, since they have to act as life-coach, father-confessor, camp counselor, and seducer, all at once. Also helps if you hand out lollipops.

Then again, shooting on the fly with the hope of capturing something essential about a person who is paying you zero attention is also fraught with risk, since you could crank off fifty frames and still go home without that person revealing anything real within the given time-frame. As with most issues photographic, there is no solution that works all of the time. I do find that one particular class of person affords you a slight edge in candid work, and that is performers. Catch a piece of them in the act of playing, singing, dancing, becoming, and you get as close to the heart of their essence that you, as an outsider, are ever going to get. If they are submerged in being, you might be lucky enough to witness something supernatural.

The more people lose themselves in a quest for the perfect sonata, the ultimate tap step, or the big money note, the less they are trying to give you a “version” of themselves, or worse yet, the rendition of themselves that they think plays well for the camera. As for you, candids work like any other kind of street photography. It’s on you to sense the moment as it arrives and grab it. It’s anything but easy, but better, when it works, then sitting someone amidst props and hoping they won’t freeze up on you.

There are two ways to catch magic in a box when it comes to portraits. One is to have a tremendous relationship with the person who is sitting for you, and the other is to be the best spy in the world when plucking an instant from a real life that is playing out in front of you. You have to know which tack to take, and where the best image can be extracted.

AVOIDING THE BURN

AS A PHOTOGRAPHER, YOU CAN EMPATHIZE WITH THAT FAMOUS MOTH AND HIS FATAL FASCINATION with a candle flame….especially if you’ve ever flirted too close to the edge of a blowout with window light. You want to gobble up as much of that golden illumination as possible without singeing your image with a complete white-hot loss of detail. Too much of a good thing and all that.

However, a window glowing with light is one of the most irresistible of candies for a shooter, and you can fill up a notebook with attempted end-arounds and tricks to harvest it without getting burned. Here’s one cheap and easy way:

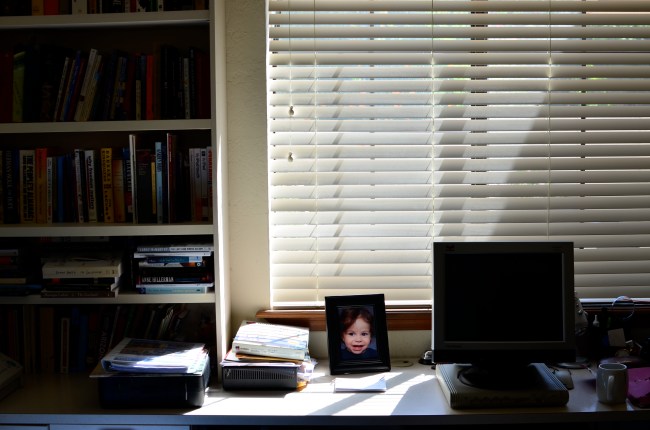

In this first attempt to capture the early morning shadows and scattered rays in my office at 1/100 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, you’ll see that the window is a little too hot, and that nearly everything ahead of the window is rendered into a silhouette. And that’s a shame, since the picture, to me, should be not only about the window light, but also its role in partially lighting a dark room. I don’t want to make an HDR here, since that will completely over-detail the stuff in the dark and look un-natural. All I really need is a hint of room light, as if a small extra bit of detail has been illuminated by the window, but just that….a small bit.

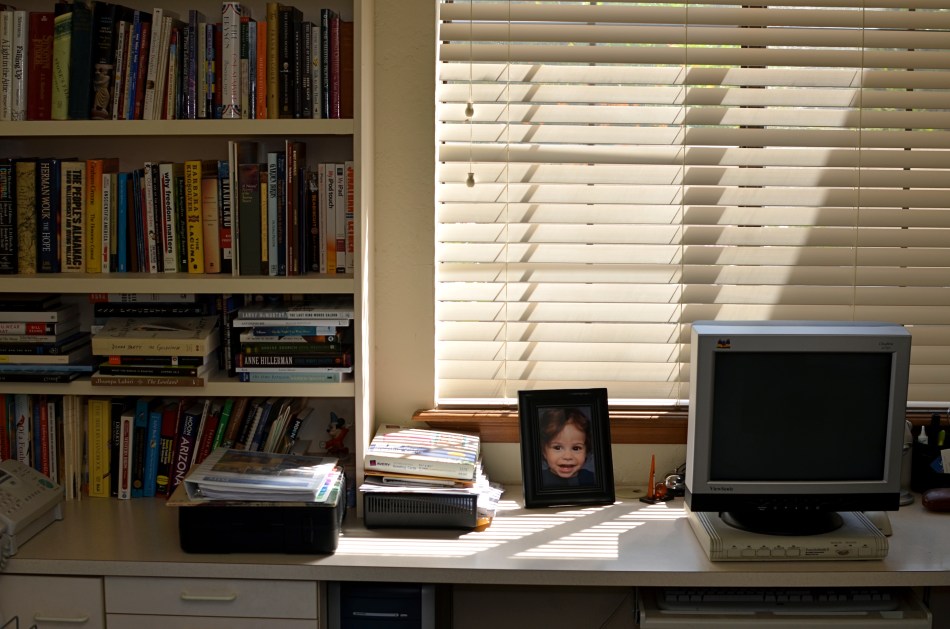

In the second attempt, I have actually halved the shutter speed to 1/200 to underexpose the window, but have also used my on-camera flash with a bounce card to ricochet a little light off the ceiling. I am almost too far away for the flash to be of any real strength, but that’s exactly what I’m looking for: I want just a trace of it to trail down the bookshelf, giving me some really mild color and allowing a few book titles to be readable. The bounce plus the distance has weakened the flash to the point that it plausibly looks as if the illumination is a result of the window light. And since I’ve underexposed the window, even the wee bit of flash hasn’t blown out the slat detail from the blinds.

Overall, this is a cheap and easy fix, happens in-camera, and doesn’t call attention to itself as a technique. There are two kinds of light: the light that is natural and the light that can be made to appear natural. If you can make the two work smoothly together, you can fly close to the flame while avoiding the burn.

THE FULLNESS OF EMPTY

By MICHAEL PERKINS SCIENCE TELLS US THAT SOME HUSBANDS HEAR THE QUESTION, “DID YOU TAKE THE TRASH OUT?” more often than any other phrase over the course of their married life. If you are an intrepid road warrior, you may hear more of something like “do you know where you’re going?” or “why don’t you just stop and ask for directions?”. If you’re a less than optimum companion, the most frequently heard statement might be along the lines of “and just where have you been?”. For me, at least when I have a camera in my hands, it’s always been “why don’t you ever take pictures of people?”

Why, indeed.

Of course, I contend that, if you were to take a random sample of any 100 of my photographs, there would be a fair representation of the human animal within that swatch of work. Not 85% percent, certainly, but you wouldn’t think you were watching snapshots from I Am Legend. However, I can’t deny that I have always seen stories in empty spaces or building faces, stories that may or may not resonate with everyone. It’s a definite bias, but it’s one of the closest things to a style or a vision that I have.

I think that absent people, as measured in their after-echoes in the places where they have been, speak quite clearly, and I am not alone in this view. Putting a person that I don’t even know into an image, just to demonstrate scope or scale, can be, to me, more dehumanizing than taking a picture without a person in it. My people-less photos don’t strike me as lonely, and I don’t feel that there is anything “missing” in such compositions. I can see these folks even when they are not there, and, if I do my job, so can those who view the results later.

Are such photographs “sad”, or merely a commentary on the transitory nature of things? Can’t you photograph a house where someone no longer lives and conjure an essence of the energy that once dwelt within those walls? Can’t a grave marker evoke a person as well as a wallet photo of them in happier times? I ask myself these questions, along with other crucial queries like, “what time is the game on?” or, “what do you have to do to get a beer in this place?” Some answers come quicker than others.

I can’t account for what amounts to “sad” or “lonely” when someone else looks at a picture. I try to take responsibility for the pictures I make, but people, while a key part of each photographic decision, sometimes do not need to serve as the decisive visual component in them. The moment will dictate. So, my answer to one of life’s most persistent questions is a polite, “why, dear, I do take pictures of people.”

Just not always.

THE (LATENT) BLUES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WE HAVE CONTROL OVER NEARLY EVERY PART OF THE PHOTOGRAPHIC PROCESS BUT… ACCESS. We can learn to master aperture, exposure, composition, and many other basics of picture making, but we can’t help the fact that we are typically at our shooting location for one time of day only.

Whatever “right now” may be….morning, afternoon, evening….it usually includes one distinct period in the day: the pier at sunset, the garden at break of dawn. Unless we have arranged to spend an extended stretch of time on a shoot, say, chasing the sun and shadows across a daylong period from one location at the Grand Canyon or some such, we don’t tend to spend all day in one place. That means we get but one aspect of a place…however it’s lit, whoever is standing about, whatever temporal events are native to that time of day.

Many locations that are easily shot by day are either unavailable or technically more complex after sundown. That’s why the so-called “day for night” effect appeals to me. As I had written sometime back, the name comes from the practice Hollywood has used for over a hundred years to save time and ensure even exposure by shooting in daylight and either processing or compensating in the camera to make the scene approximate early night.

In the case of the image you see up top, I have created an illusion of night through the re-contrasting and color re-assignment of a shot that I originally made as a simple daylight exposure. In such cases, the mood of the image is completely changed, since the light cues which tell us whether something is bright or mysterious are deliberately subverted. Light is the single largest determinant of mood, and, when you twist it around, it reconfigures the way you read an image. I call these faux-night remakes “latent blues”, as they generally look the way the sky photographs just after sunset.

This effect is certainly not designed to help me avoid doing true night-time exposures, but it can amplify the effect of images that were essentially solid but in need of a little atmospheric boost. Just because you can’t hang around ’til midnight, you shouldn’t have to do without a little midnight mood.

TURN THE PAGE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’M VERY ACCUSTOMED TO BEING STOPPED IN MY TRACKS AT A PHOTOGRAPH THAT EVOKES A BYGONE ERA: we’ve all rifled through archives and been astounded by a vintage image that, all by itself, recovers a lost time.

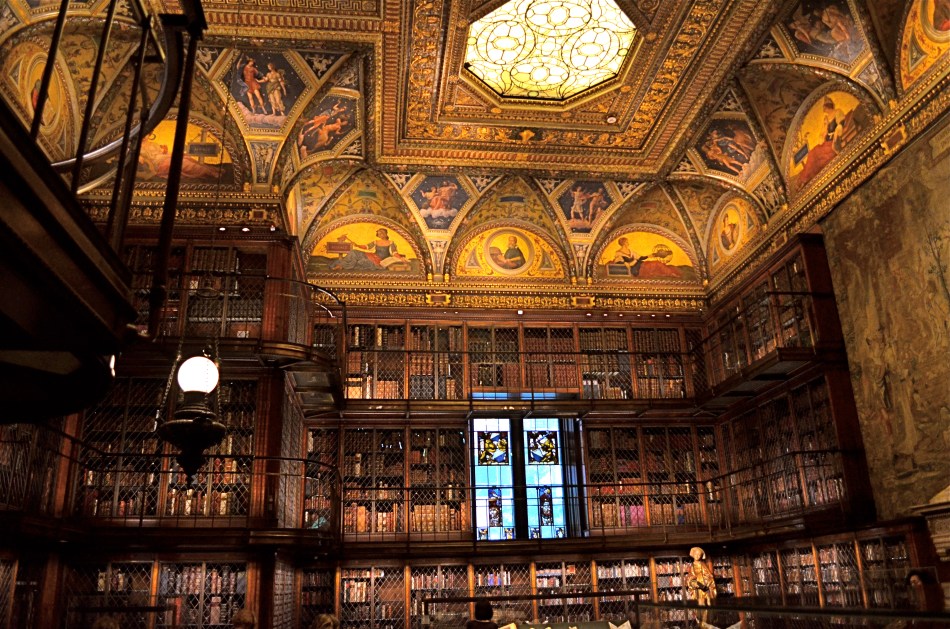

It’s a little more unsettling when you experience that sense of time travel in a photo that you just snapped. That’s what I felt several weeks ago inside the main book trove at the Morgan Library in New York. The library itself is a tumble through the time barrier, recalling a period when robber barons spent millions praising themselves for having made millions. A time of extravagant, even vulgar displays of success, the visual chest-thumping of the Self-Made Man.

The private castles of Morgan, Carnegie, Hearst and other larger-than-life industrialists and bankers now stand as frozen evidence of their energy, ingenuity, and avarice. Most of them have passed into public hands. Many are intact mementos of their creators, available for view by anyone, anywhere. So being able to photograph them is not, in itself, remarkable.

A little light reading for your friendly neighborhood billionaire. Inside the Morgan Library in NYC.

No, it’s my appreciation of the fact that, today,unlike any previous era in photography, it’s possible to take an incredibly detailed, low-light subject like this and accurately render it in a hand-held, non-flash image. This, to a person whose life has spanned several generations of failed attempts at these kinds of subjects, many of them due to technical limits of either cameras, film, or me, is simply amazing. A shot that previously would have required a tripod, long exposures, and a ton of technical tinkering in the darkroom is just there, now, ready for nearly anyone to step up and capture it. Believe me, I don’t dispense a lot of “wows” at my age, over anything. But this kind of freedom, this kind of access, qualifies for one.

This was taken with my basic 18-55mm kit lens, as wide as possible to at least allow me to shoot at f/3.5. I can actually hand-hold fairly steady at even 1/15 sec., but decided to play it safe at 1/40 and boost the ISO to 1000. The skylight and vertical stained-glass panels near the rear are WINOS (“windows in name only”), but that actually might have helped me avoid a blowout and a tougher overall exposure. So, really, thanks for nothing.

On of my favorite Twilight Zone episodes, the one about Burgess Meredith inheriting all the books in the world after a nuclear war, with sufficient leisure to read his life away, was entitled “Time Enough At Last”. For the amazing blessings of the digital age in photography, I would amend that title by one word:

Light Enough…At Last.

THE POLAROID EFFECT

BY MICHAEL PERKINS

I’VE BEEN TRYING TO FIND A WAY TO DESCRIBE THE COMBINATION OF HOPE AND ANXIETY THAT ATTENDS MY EVERY USE OF A SMARTPHONE CAMERA. Coming, as do many geezers of my era, from a tradition of full-function, hands-on, manual cameras, I have had a tough time embracing these miraculous devices, simply because of the very intuitive results that delight most other people.

But: it’s a little more complicated than my merely being a control freak or a techno-snob.

What’s always perplexing to me is that I feel that the camera is making far too many choices that it “assumes” I will be fine with, even though, in many cases, I am flat-out amazed at how close the camera delivers the very image I had in mind in the first place. It doesn’t exactly make one feel indispensable to the process of picture-making, but that’s a bug inside my own head and I gotta deal with it.

I think what I’m feeling, most of the time, is what I call the “Polaroid Effect”. To crowd around family or friends just moments after clicking off a memory with the world’s first true instant film cameras, those bulky bricks of the Mad Men era, was to share a collectively held breath: would it work? Did I get it right? Then as now, many “serious” photographers were reluctant to trust a Polaroid over their Leicas or Rolliflexes. Debate raged over the quality of the color, the impermanence of the prints, the limited lenses, the lack of negatives, and so on. Well, said the experts, any idiot can take a picture with this.

Well, that was the point, wasn’t it? And some of us “idiots” learned, eventually, to take good pictures, and moved on to other cameras, other lenses, better pictures, a better eye. But there was that maddening wait to see if you had lucked out with those square little glimpses of life. The uncertainty of trusting this…machine to get your pictures right.

And yet look at the above image. I asked a lot in this frame, with wild amounts of burning hot sunlight, deep shadows, and every kind of contrast in between just begging for the camera to blow it. It didn’t. I’m actually proud of this picture. I can’t dismiss these devices just because they nudge me out of my comfort zone.

Smartphone cameras truly extend your reach. They go where bulkier cameras don’t go, prevent more moments from being lost, and are in a constantly upward curve of technical improvement. People can and do make astounding pictures with them, and I have to remind myself that the ultimate choice…that of what to shoot, can never be taken away just because the camera I’m holding is engineered to protect me from my own mistakes.

FALL-OFF AS LEAD-IN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

USING “LEADING LINES” TO PULL A VIEWER INTO AN IMAGE IS PRETTY MUCH COMPOSITION 101. It’s one of the best and simplest ways to overcome the flat plane of a photograph, to simulate a feeling of depth by framing the picture so the eye is drawn inward from a point along the edge, usually by use of a bold diagonal taking the eye to an imagined horizon or “vanishing point”. Railroad tracks, staircases, the edge of a long wall, the pews in a church. We all take advantage of this basic trick of engagement.

Bright light into subdued light: a natural way to pull your viewer deeper into the picture. 1/100 sec., f/1.8, ISO 650, 35mm.

One thing that can aid this lead-in effect even more is shooting at night. Artificial lighting schemes on many buildings “tell” the eye what the most important and least important features should be…where the designer wants your eye to go. This means that there is at least one angle on many city scenes where the light goes from intense to muted, a transition you can use to seize and direct attention.

This all gives me another chance to preach my gospel about the value of prime lenses in night shots. Primes like the f/1.8 35mm used for this image are so fast, and recent improvements in noiseless ISO boosts so advanced, that you can shoot handheld in many more situations. That means time to shoot more, check more, edit more, get closer to the shot you imagined. This shot is one of a dozen squeezed off in about a minute. The reduction of implementation time here is almost as valuable as the speed of the lens, and, in some cases, the fall-off of light at night can act as a more dramatic lead-in for your shots.

MINUTE TO MINUTE

Going, Going: Dusk giveth you gifts, but it taketh them away pretty fast, too. 1/40 sec., f/3.5, ISO 200, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

VOLUMES HAVE BEEN WRITTEN ABOUT THE WONDROUS PHENOMENON OF “GOLDEN HOUR“, that miraculous daily window of time between late afternoon and early evening when shadows grow long and colors grow deep and rich. And nearly all authors on the subject, whatever their other comments, reiterate the same advice: stay loose and stay ready.

Golden hour light changes so quickly that anything that you are shooting will be vastly different within a few moments, with its own quirky demands for exposure and contrast. Basic rule: if you’re thinking about making a picture of an effect of atmosphere, do it now. This is especially true if you are on foot, all alone in an area, packing only one camera with one lens. Waiting means losing.

The refraction of light through clouds, the angle of the sun as it speeds toward the horizon, the arrangement between glowing bright and super-dark….all these variables are shifting constantly, and you will lose if you snooze. It’s not a time for meditative patience. It’s a time for reactivity.

I start dusk “walkarounds” when all light still looks relatively normal, if a bit richer. It gives me just a little extra time to get a quick look at shots that may, suddenly, evolve into something. Sometimes, as in the frame above, I will like a very contrasty scene, and have to shoot it whether it’s perfect or not. It will not get better, and will almost certainly get worse. As it is, in this shot, I have already lost some detail in the front of the building on the right, and the lighted garden restaurant on the left is a little warmer than I’d like, but the shot will be completely beyond reach in just a few minutes, so in this case, I’m for squeezing off a few variations on what’s in front of me. I’ve been pleasantly surprised more than once after getting back home.

What’s fun about this particular subject is that one half of the frame looks cold, dead, “closed” if you will, while there is life and energy on the left. No real story beyond that, but that can sometimes be enough. Golden hour will often give you transitory goodies, with its more dramatic colors lending a little more heft to things. I can’t see anything about this scene that would be as intriguing in broad daylight, but here, the hues give you a little magic.

Golden hour is a little like shooting basketballs at Chuck E. Cheese. You have less time than you’d like to be accurate, and you may or may not get enough tickets for a round of Skee-Ball.

But hey.

SOME OF MY BEST FRIENDS ARE (NOT) PHOTOGRAPHERS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE WAS A BRIEF MOMENT, WHEN PHOTOGRAPHY WAS A NOVELTY, when it was thought to be in some kind of winner-take-all death match with painting. That fake war lasted but a moment, and the two arts have fed (and fed upon) each other to varying degrees ever since. Both painting and photography have passed through phases where they were consciously or unconsciously emulating each other, and I dare say that all photographers have at least a few painter’s genes in their DNA. The two traditions just have too much to offer to live apart.

One of my favorite examples of “light sculpting”, the artistic manipulation of illumination for maximum mood, came to me not from a photographer, but from one of the finest illustrators of the early twentieth century. Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966) began his career as a painter/illustrator for fanciful fiction from Mother Goose to The Arabian Nights. Then, as color processes for periodicals became more sophisticated after 1900, he seamlessly morphed into one of the era’s premier magazine artists, working mostly for ad agencies, and most famously for his series of magnificently warm light fantasies for Edison Mazda light bulbs.

Parrish’s Mazda ads are dazzling arrangements of pastel blues, golden earth tones, dusky oranges, and hot yellows, all punched up to their most electrically fantastic limits. Years before photographers began to write about “golden hours” as the prime source of natural light, Parrish was showing us what nature seldom could, somehow making his inventions seem a genuine part of that nature. The stuff is mesmerizing. See more of his best at: http://www.parrish.artpassions.net/

During a recent trip to the high walking paths that crown Griffith Park in Los Angeles, I saw the trees and hills, at near sunset, form the perfect radiated glow of one of Parrish’s dusks. Timing was crucial: I was almost too late to catch the full effect, as shadows were lengthening and the overhanging tree near my cliffside lookout were beginning to get too shadowy. I hoped tha,t by stepping back just beyond the effective range of my on-board flash, I could fill in the front of the fence, allowing the light to decay and darken as it went back toward the tree. Too close and it would be a total blowout. Too far back, and everything near at hand would be too dark to complement the color of the sky and the hills.

After a few quick adjustments, I had popped enough color back into the foreground to make a nice authentic fake. For a moment, I was on one of Parrish’s mountain vistas, lacking only the goddesses and vestal virgins to make the scene complete. You’d think that, this close to Hollywood, you could get Central Casting to send over a few extras. In togas.

Next time.

BALLET OF HORROR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE USED TO BE A MOVEMENT IN FINE ARTS CALLED THE “ASHCAN SCHOOL”, WHICH SOUGHT TO SHOW POWER AND BEAUTY in banal or even repellent urban realities. It posed a question that continues to stoke debate within photography to this day: how much should art engage with things that are horrible? Is the creative act vital when it shows us ugliness? More importantly, is it vital because it shows us these things? And, if we choose to depict beauty to the exclusion of the ugly, is our art somehow less authentic?

The whole matter may come down to whether you see photography as a constructed interpretation of the world, kind of a visual poem, or as a sort of journalism. Of course, the medium has been shown to be wide enough for either approach, and perhaps the best work comes from struggling to straddle both camps. A world of gumdrops and lollipops can be just as pretentious and empty as a world constructed exclusively of the grisly, and I think each image has to be defined or justified as a separate case. That said, finding a ying/yang balance between both views within a single image is rare.

Falling, as I did, under the influence of landscape photographers at a really early age, I have had to learn to search for a kind of rough ballet in things that I find disturbing. I’m not saying that it’s hampered my work: far from it. Look at it another way: as a missionary, you can plant crops and build hospitals for your village, but you still have to address the area’s cholera and dysentery. It’s just a part of its life.

The image above was pretty much placed right in my path the other day as I walked to enter an urban drugstore, and, as horrified as I was by the likely origin of this savage souvenir, I had to also acknowledge it as a Darwinian study of beauty and design. The virtually intact nature of the wing, contrasted with the brutal evidence of its detachment from its owner, made for an unusual transition from poetry to chaos within a single image. Many might ask, how could you make that picture? And it’s a hard question to answer. Another question that would be just as difficult to answer: how could I not?

Certainly, I won’t be entering this in Audubon magazine’s annual photo contest: it’s also no one’s idea of cutest kitty or beautiful baby. But it is one of the most unique combinations of sensation I have ever seen, and I did not want to forget it, nightmares and all. Because we live, and take pictures in, the world at large.

Not just the world we want.

MAGNIFICENT RUIN

Clay pre-firings and molds for bronze bells at Paolo Soleri’s COSANTI studios in Paradise Valley, Arizona. 1/20 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

by MICHAEL PERKINS

IN 1956, ARCHITECT PAOLO SOLERI BEGAN THE FIRST MINIATURE DEMONSTRATION OF WHAT WOULD BECOME HIS LIFE’S WORK, an experimental, self-contained, sustainable community he called Cosanti. Erecting a humble home just miles from his teacher Frank Lloyd Wright’s compound at Taliesin West, in what was then the wide-open desert town of Paradise Valley, Arizona, he started sand-casting enormous concrete domes to serve as the initial building blocks of a new kind of ecological architecture. And, over the next half-century, even as Soleri would call Paradise Valley his home, he would construct bigger versions of his dream city, now renamed Arcosanti, on a vast patch of desert between Phoenix and Flagstaff.

The project, which at his death in 2013 was still unrealized, was funded over the years by the sales of Soleri’s custom fired bronze and clay wind bells, which became prized by Arizona visitors from all over the world. At present, his early dwellings still stand, as do the twisting, psychedelic paths and concrete arches that house his smelting forges, his kilns, the Cosanti visitor center, and a strange spirit of both wonder and dashed dreams. It is a magnificent ruin, a mad and irresistible mixture of textures for photographers.

One of COSANTI’s bizarre dwellings, scattered amongst the compound’s forges and kilns. 1/400 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

Name the kind of light…….brilliant sun, partial shade, catacomb-like shadows, and you’ve got it. Name the material, from wood to stone to concrete to stained glass, and it’s there. The terrain of the place, even though it’s now surrounded by multi-million dollar mansions, still bears the lunar look of a far-flung outpost. It’s Frank Lloyd Wright in The Shire. It’s Fred Flintstone meets Dune. It continues to be a bell factory, and a working architectural foundation. And it’s one of my favorite playgrounds for testing lenses, flexing my muscles, trying stuff. It always acts as a reboot on my frozen brain muscles, a place to un-stall myself.

Here’s to mad dreamers, and the contagion of their dreams.

DARKNESS AS SCULPTOR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN DAYLIGHT PHOTOGRAPHY, THE DEFAULT ACTION TENDS TO BE TO SHOW EVERYTHING. Shadows in day scenes are a kind of negative reference to the illuminated objects in the frame, but it is those objects, and not the darkness, that defines space. In this way shady areas are a kind of decor, an aid to recognition of scale and depth.

At night, however, the darkness truly plays a defining role, reversing its daylight relationship to light. Dark becomes the stuff that night photos are sculpted from, creating areas that can remain undefined or concealed, giving images a sense of understatement, even mystery. Not only does this create compelling compositions of things that are less than fascinating in the daytime, it allows you to play “light director” to selectively decide how much information is provided to the viewer. In some ways, it is a more pro-active way of making a picture.

This bike shop took on drastically different qualities as the sun set. 1/40 sec., f/3.5, ISO 100, 18mm.

I strongly recommend walkabout shoots that span the complete transition from dusk to post-sunset to absolute night. Not only will the quickly changing quality of light force you to make decisions very much in-the-moment, it allows for a vast variance in the visual power of your subjects that is starkly easy to measure. It’s a great practice lab for shooting completely on manual, and, depending on the speed of your chosen lens (and greater ISO flexibility in recent cameras), makes relatively noise -free, stable handheld shots possible that were unthinkable just a few years ago. One British writer I follow recently remarked, concerning ISO, that “1600 is the new 400”, and he’s very nearly right.

So wander around in the dark. The variable results force you to shoot a lot, rethink a lot, and experiment a lot. Even one evening can accelerate your learning curve by weeks. And when darkness is the primary sculptor of a shot, lovely things (wait for the bad pun) can come to light (sorry).

SOFT EDGES, HARD TRUTHS

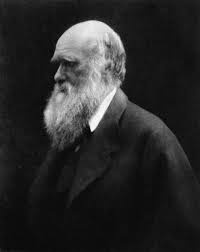

Charles Darwin sits for Julia Margaret Cameron. What she sacrificed in sharpness she gained in naturalness.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHATEVER MARVELS CURRENT TECHNOLOGY ALLOW US TO ACHIEVE IN PHOTOGRAPHY, there is one thing that it can never, ever afford us: the ability to be “present at the creation”, actively engaged at the dawn of an art in which nearly all of its practitioners are doing something fundamental for the very first time. The nineteenth century now shines forth as the most open, experimental and instinctive period within all of photography, peopled with pioneers who achieved things because there was no tradition to discourage them, mapping out the first roads that are now our well-worn highways. It is an amazing, matchless time of magic, risk, and invention.

Much of it was largely mechanical in nature, with the 1800’s marked by rapidly changing technical means for making images, for finding faster recording media and sharper lenses. The true thrill of early photography comes, however, from those who conjured ways of seeing and interpreting the world, rather than merely making a record of it. In some ways, creating a camera

Most 19th photographers could barely capture people as objects: Cameron transformed them into subjects.

facile enough to fix portraits on glass was easy. compared with the evolving philosophy of how to portray a person, what part of the subject to capture within the frame. And it was in this latter wizardry that Julia Margaret Cameron entered the pantheon of genuine genius.

Born to courtly British comfort in India in 1815, Cameron, largely a hobbyist, was one of the first photographers to move beyond the rigid, lifeless portraits of the era to generate works of investigation into the human spirit. She was technically bound by the same long exposures that made sitting for a picture such torture at the time, but, somehow, even though she endlessly posed, cajoled, and even bullied her subjects into position, she nonetheless achieved an intimacy in her work that the finest studio pros of the early 19th century could not approximate. Far from being put off by the softness that resulted from long exposures, Cameron embraced it, imbuing her shots with a gauzy, ethereal quality, a human look that made most other portraits look like staged lies.

In many cases, Julia Margaret Cameron’s eye has become the eye of history, since many who sat for her, like Charles Darwin, seldom or ever sat again for anyone else, making her view of their greatness the official view. And while she only practiced her craft for a scant fifteen years, no one who hopes to illuminate a personality in a photographic frame can be free of her heavenly mix of soft edges and hard truths.

Extra Credit: for more samples of JMC’s work, take this link to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Cameron exhibition page:

http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2013/julia-margaret-cameron