ROOM WITH A VIEW

This 1820’s view from the upper floor of Nicéphore Niépce’s house is generally acknowledged as the first true photograph, revealing rough details of a distant pear tree, a slanted barn roof, and the secondary wing of the estate (at right).

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MANY OF THE MOST IMPORTANT SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERIES ARE ACTUALLY DETOURS, things unearthed by accident in search of something completely different. Marconi was not looking to create the entertainment medium known as radio, but merely a wireless way to send telegraphs. The tough resin known as Bakelite was originally supposed to be a substitute for shellac, since getting the real thing from insects was slow and pricey. Instead, it became the first superstar of the plastics era, used to making everything from light plugs to toy View-Masters.

And the man who, for all practical purposes, invented photography was merely seeking a shortcut for the tracing of drawings.

Nicéphore Niépce, born in France in 1765, plied his trade in the new techniques of lithography, but fell short in his basic abilities as an artist, and searched for a way to get around that shortcoming by technical means. He became proficient in the creation of images with a camera obscura, a light-tight box with a pinhole on one side which projected an inverted picture of whatever it was pointed at on the opposite inside wall of the container, the pinhole acting as a glassless, small-aperture lens. Larger versions of the gadget were used by artists to project a subject onto an area from which tracings of the image could be done, then finished into drawings. Niépce grew impatient with the long lag time involved in the tracing work and began to experiment with various compounds that might chemically react to light, causing the camera’s image to be permanently etched onto a surface, making for a quicker and more accurate reference study.

Niépce tried a combination of fixing chemicals like silver chloride and asphalt, burning faint images onto surfaces ranging from glass to paper to lithographic stone. Some of his earliest attempts registered as negatives, which faded to complete black when observed in sunlight. Others resulted in images which could be used as a master from which to print other images, effectively a primitive kind of photocopy. Finally, having upgraded the quality of his camera obscura and coating a slab of pewter with bitumin, Niépce, around 1827 successfully exposed a permanent, if cloudy image from the window of his country house in La Gras. His account recalled that the exposure took eight hours, but later scientific recreations of the experiment believe it could actually have taken several days. Even at that, Niépce might have recorded a good deal more detail in the image had he waited even longer. In an ironic lesson to all impatient future shooters, the world’s first photograph had, in fact, been under-exposed.

Rather than merely create a short-cut for sketch artists, Nicéphore Niépce’s discovery, which he called heliography (“sun writing”), resulted in a new, distinctly different art that would compete with traditional graphics, forever changing the way painters and non-painters viewed the world. Centuries later, harnessing light in a box is still the task at hand, and the eternally novel miracle of photography.

COST ANALYSIS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S SAFE TO SAY THAT, TO DATE, MOST OF THE WRITINGS THAT COMPARE FILM PHOTOGRAPHY TO DIGITAL center on visual or aesthetic criteria. The grain of film, the value range of pixels, the differences in the two types of workflow, the comparative sizes of sensors, and so forth. However, in certain shooting situations, what strikes me as the main advantage of digital is crassly…..monetary.

It’s simply cheaper.

Now, that’s no small thing. Consider that, with film, a very real cost comes attached to every single frame, both masterpiece and miss. Now, try to compute how much film you must consume in order to travel from one end of a learning curve to the other in trying to master a new lens or technique. Simply, every shot on the way to “that’s it!” is a “damn, that’s not it”, and both cost money. Now recall those shoots where the conditions are so strange or variable that the only way to get the right shot is to take lots of wrong ones, and remember as well, that, after clicking off all those frames, you had to wait (with the meter running), until either the processor or your own darkroom skill even told you that you were on the wrong track.

Assume further that you screwed up several rolls of premium Kodachrome before stumbling on the right approach, and that all of those rolls are now firmly in the “loss” column. You re-invest, re-load, and hope you learned your lesson. Ca-ching.

The shot that you see above demonstrates why shooting in digital speeds up your practice time, at a fraction of the cost of film, while giving you feedback that allows you to adjust, shoot, and adjust again before the conditions in front of you are lost. What you see is a late dusk on a dark lagoon just inland of a stretch of ocean in Point Dana, California, strewn with waves of bathing birds and shifting pools of ripples. The pink of the clouds on the horizon will be gone in a matter of minutes. Also, I’m shooting through a narrow-gauge opening in a chain-link fence, causing dark vignettes on every other shot. Moreover, I’m using a plastic lens, making everything soft even softer, especially at the edges.

So add all these factor together and the emotional curve of the shoot is click-damn-click-whoops-click-click-damn. But, since it’s digital, the bad guesses come back fast, and so does the ability to adjust. Bottom line: I know I will likely walk away with something generally usable.

More importantly, photography no longer has the power to price so many of us out of the practice. That means that more images make it to completion, and, of course, that can also mean a global gallery flooded with mediocrity. Hey, I get that. But I also get a fighting chance at grabbing pictures that used to belong only to the guy who could afford to stand and burn twelve rolls of film.

And hope like hell.

THE EYES HAVE IT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WINDOW TO THE SOUL: that’s the romantic concept of the human eye, both in establishing our emotional bonds with each other and, in photography, revealing something profound in portraiture. The concept is so strong that it is one of the only direct links between painting (the way the world used to record emotional phenomena) and photography, which has either imitated or augmented that art for two full centuries. Lock onto the eyes, we say, and you’ve nailed the essence of the person.

So let’s do a simple comparison experiment. In recent years, I’ve begun to experiment more and more with selective-focus optics such as the Lensbaby family of art lenses. Lensbabies are unabashedly “flawed” in that they are not designed to deliver uniform focus, but, in fact, use the same aberrations that we used to design out of lenses to isolate some subjects in intensely sharp areas ( so-called “sweet spots”) surrounded by gradually increasing softness.

As a great additional feature, this softness can even occur in the same focal plane as a sharply rendered object. That means that object “A”, five feet away from the camera, can be quite blurry, while object “B”, located just inches to the side of “A”, and also five feet from the camera, can register with near-perfect focus. Thus, Lensbaby lenses don’t record “reality”: they interpret mood, creating supremely subjective and personal “reads” on what kind of reality you prefer.

Exact same settings as the prior example, but with a slightly tighter focus of the Lensbaby’s central “sweep spot”.

Art lenses can accentuate what we already know about faces, and specifically, eyes…that is, that they remain vital to the conveyance of the personality in a portrait. In the first sample, Marian’s entire face takes on the general softness of the entire frame, which is taken with a Lensbaby Sweet 35 lens at f/4 but is not sharply focused in the central sweet spot. In the second sample, under the same exposure conditions, there is a conscious effort to sharpen the center of her face, then feather toward softness as you radiate out from there.

The first exposure is big on mood, with Marian serving as just another “still life” object, but it may not succeed as a portrait. The second shot uses ambient softness to keep the overall intimacy of the image, but her face still acts as a very definite anchor. You “experience” the picture first in her features, and then move to the data that is of, let’s say, a lower priority.

Focus is negotiated in many different ways within a photograph, and there is no empirically correct approach to it. However, in portrait work, it’s hard to deny that the eyes have it, whatever “it” may be.

Windows to the soul?

More like main clue to the mystery.

TAKING OFF THE TRAINING WHEELS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S HARD TO BE ANGRY WITH ANY TREND THAT MAKES PHOTOGRAPHY MORE DEMOCRATIC, or puts cameras into more hands. Getting more voices in the global conversation of image-making is generally a great things. However, it comes with a price, one which may make many people actually give up or stagnate in their growth as photographers.

We may be killing ourselves, or at least our art, with convenience.

Cameras, especially in mobile devices, have exponentially grown in ease (and acuity) of use over the last fifty years, but they are actually teaching people less and less about what, technically, is happening in the making of an image. The nearly intuitive logic of smaller and easier cameras means that many people, while busily snapping away and producing billions of pictures, are being more and more estranged from any real knowledge of how it’s all being done.

This is a vicious circle, since it guarantees that a greater number of us will be more and more dependent upon our cameras to make the bulk of the creative decisions for us, more obliged to accept what the camera decides to give us. In some very real way, we are being shortchanged by never having had to work with a garbage camera. Let me explain that.

Being forced to do creative work with an unyielding or primitive tool puts the responsibility for (and control of) the art back on the artist. Those who began their shooting careers with limited box cameras understand this already. If you start making pictures with a device that is too limited or “dumb” to do your bidding, then you have to devise work-arounds to get results. That means you learn more about what light does. You learn what ideal or adverse conditions look like. You see what failure is, and begin to dissect what didn’t work for a stronger understanding of what may work next time. You learn to ride a bike without training wheels, and thus never need them.

The dark lobby of New York’s Chrysler building: An extremely challenging setting for low-light photography. I screwed this up on a cosmic scale, but I learned a ton. Shooting on automodes, I would have learned precisely…nothing. And the picture still would have stunk.

The above image, taken on manual settings in a less-than-ideal setting, has about a dozen things wrong with it, but the mistakes are all my mistakes, so they retain their instructive power. If something was blown, I know how it can be corrected, since I’m the one who blew it. There is a clear linear learning process that benefits from making bad pictures. And if my camera had done everything itself and the picture still reeked, then I’d be stuck with both failure and ignorance.

Cameras that remove the risk of failure also remove the chance of accidental discovery. If you always get acceptable images, you’re less likely to ask what lies beyond….what, in effect, could be better. You accept mediocrity as a baseline of quality. And editing tools that consist mostly of corrective solutions, from straightening to sharpening, keep you from addressing those errors in the camera, and that, too, robs you of valuable experience.

Convenience, in any art medium, can either abet or prevent excellence. The amount of curiosity and hunger in the individual is the decisive factor in moving from taking to making pictures. For my money, if you’re going to grind out the process of becoming an artist, you can’t rely on equipment that is designed to protect you from yourself.

ADDITION BY SUBTRACTION

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHIC COMPOSITION IS A CONSCIOUS PRIORITIZING OF EVERYTHING WITHIN A PICTURE’S FRAME, a ruthless process of demanding that everything inside that square justify its presence there. When we refer to the power of an image, we are really talking about the sumtotal of all the decisions that were made, beforehand, of what to include or lose in that image. Without that deliberate act of selection, the camera merely records everything it’s pointed at. It cannot distinguish between something essential and something extraneous. Only the human eye, synched to the human mind, can provide the camera with that context.

Many of our earliest photographs certainly contain the things we deem important to the picture, but they also tend to include much too much additional information that actually dilutes the impact of what we’re trying to show. In one of my own first photos, taken when I was about twelve, you can see my best friend standing on his porch…absolutely…..along with the entire right side of his house, the yard next door, and a smeary car driving by. Of course, my brain, viewing the result, knew to head right for his bright and smiling face, ignoring everything else that wasn’t important: however, I unfairly expected everyone else, looking at all the auxiliary junk in the frame, to guess at what I wanted them to zero in on.

Jump forward fifty years or so, to my present reality. I actively edit and re-edit shots before they’re snapped, trying to pare away as much as I can in pictures until only the basic storytelling components remain….that is, until there is nothing to distract the eye from the tale I’m attempting to tell. The above image represents the steps of this process. It began as a picture of a worn kitchen chair in a kitchen, then the upper half of the chair near part of a window in the kitchen, and then, as you see above, only part of the upper slats of the chair with almost no identifiable space around them. That’s because my priorities changed.

At first, I thought the entire kitchen could sell the idea of the worn, battered chair. Then I found myself looking at the sink, the floor, the window, and…oh, yeah, the chair. Less than riveting. So I re-framed for just the top half of the chair, but my eye was still wandering out the window, and there still wasn’t enough visible testimony to the 30,000 meals that the chair had presided over. So I came in tighter, tight enough to read the scratches and discolorations on just a part of the chair’s back rest. They were eloquent enough, all by themselves, to convey what I wanted, without the rest of the chair or anything else in the room to serve as competition. So, in this example, it took me about five trial frames to teach myself where the picture was.

And that’s the point, although I still muff the landing more often than I stick it (and probably always will). To get stronger compositions, you have to ask every element in the picture, “so what do you think you’re doing here?” And anyone who doesn’t have a good answer….off to the principal’s office.

ESCAPING THE DARKNESS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

TO A PHOTOGRAPHER, THE ENTIRE WORLD IS PRETTY MUCH A “PUBLIC PLACE“, or, more properly, his own personal work space. However, that dreamy viewpoint is not shared by the world at large, and shooters who try to harvest their shots in museums, theatres, office lobbies and other popular gathering points are finding, more and more, that they are about as welcome as a case of shingles unless they are (a) quick (b) unobtrusive and (c) polite to the point of fawning.

It’s not hard to understand why.

First, some of the excess paraphernalia that photogs pack can strike curators and security personnel as hazardous, if not downright dangerous. This view is reflected in the growing number of attractions that have, of late, prohibited the use of selfie sticks. That one I kinda get. Photographers have also taken a hit in the number of places that will permit flash of any kind, and tripods and monopods are nearly always forbidden. The real determinant in why public spaces are less inclined to play ball with photographers, however, is that they simply don’t have to. More patrons than ever rely solely on cel phones, which, in turn, have become more sensitive to low-light situations, making for shorter exposures with fewer add-ons, a technical leap that ensures that everyone will come away with at least some kind of picture. If you need a longer exposure at lower ISO (hence less noise), you still need traditional, higher-end gear, but those numbers are shrinking so much that the gatekeepers can be a lot more restrictive overall.

In many dark spaces I simply can’t find a place to stabilize my camera long enough to take an extended exposure. And, with ‘pods off the table as an option, you’re down to benches, ledges, or other precarious surfaces, and, with them, the paranoid hovering of a mother eagle guarding her eggs to steer foot traffic away from her “nest”. A remote shutter release helps, but the whole project can raise the blood pressure a bit. At least with tripods, passersby can see a set space to steer themselves clear of. A crazy man waving his arms, not so much.

Herd On The Street, 2016. A twenty-five second exposure at f/8, ISO 100, 24mm, from a camera teetering on a museum railing.

The above image was taken in one of the most light-deprived sectors of the New York Museum Of Natural History, with only soft illumination in the side showcases to redeem the pitch-black gloom. No flash would even begin to fill this enormous space, even if it were permitted, and the hall is always crowded, so resting my camera on a narrow rail, twenty-plus feet above the main floor, and going for a long exposure, is the only way for an acceptable degree of detail to emerge from the murk. My wife, who is known for nerves of steel, had to excuse herself and go elsewhere as I was setting up the shot. I couldn’t blame her.

Three or four anxious framings later, I got a workable exposure. As occurs with time exposures, people walking through the scene at a reasonable speed are rendered nearly invisible. The persons near the back of the elephant herd stood still long enough to take a flash snapshot, so their flash burst and some smudgy shadows of their bodies can be seen, as can the trailing LED light that someone else on the upper deck apparently was walking with in the upper right corner. But for this kind of shot, in these modern times, such artifacts are part of the new normal.

IT’S ALL WRONG BUT IT’S ALL RIGHT

I decided in the moment to go soft with this nature scene. Maybe I overdid it. Maybe it’s okay. Or not.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE ONLY CONSTANTS OVER THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY has been the flood tide of tutorial materials covering every aspect of exposure, composition, and light. The development of the early science of capturing images in the 19th century was accompanied, from the first, by a staggering load of “how to” literature, as the practice moved quickly from the tinkering of rich hobbyists to one of the most democratic of all the art forms. In little more than a generation, photography went from a wizard’s trick to a series of simple steps that nearly anyone could be taught.

In calling these pages the “photoshooter’s journey from taking to making”, we have made, with The Normal Eye, a deliberate choice not to add to the mountainous load of technical instruction that continues to be available in a variety of classroom settings, but to emphasize why we make photographs. This is not to say that we don’t refer to the so-called “rules” that govern the basics of creating an image, but that we believe the motives, the visions behind our attempts are even more important than just checking items off a list of techniques in the name of doing something “right”. There are many technically adept pictures which fail to engage on an emotional or aesthetic level, so the mission of The Normal Eye, then, is to start discussions on the “other stuff”, those indefinable things that make a picture “work” for our hearts and minds.

The idea of what a “good picture” is, has, over time, drifted far and wide, from photographs that mimic reality, to those that distort and fracture it, to images that are both a comment and a comment on a comment. It’s like any other long-term relationship: complicated. Like everyone else, I occasionally produce what I call a “fence-sitter” photo like the one above, which I can both excuse and condemn at the same time.

In raw technical terms, I have obviously violated a key rule with the abject softness of the image…..unless……unless it can be said to work within the context of the other things I was seeking in this subject. I was trying to stretch the envelope on how soft I could make the mix of dark foliage and hazy water in the scene, and, while I may have gone a bit too far, I still like some of what that near-blur contributes to the saturated color and lower exposure, the overall quiet tone I was trying for. Still, as of this moment, I’m still not sure whether this one is a hit or a miss. It might be on the way to something, but I just can’t say.

But that’s what the journey is about. It can’t be confined to mere technical criteria. You have to make the picture speak in your own language.

A RACE OF INCHES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU CAN VIEW THE MAIN FUNCTION OF PHOTOGRAPHY AS TWOFOLD, with the deliberate creation of a vision as one path, and the arresting of time in its motion as the other. In the first case, we plan, conceive and execute at our leisure until the image that is behind our eye emerges on the page. In the second, we are hastening to capture and cage something that is in the act of disappearing. In one instance we compose. In the other, we preserve.

Sometimes the two purposes come together in one picture, although you seldom know it until after the image is made. Take the example below. In the moment, I was struck by the light patterns that bounced across the empty space of an event room at the visitor center for the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens. I wanted to do everything I could, exposure-wise, to dramatize the play of light in this special space. In addition to trying to create an image, however, I was also scurrying to keep a special number of factors from vanishing. I was both creating and preserving.

Obviously, the light you see would have had a dramatically different effect had the room been packed with, say, bodies or furniture, so its unobstructed path was one temporary condition. Another fleeting factor was the late afternoon light, which was, in addition to being extremely changeable, also one of the rare moments of pure sun the area had seen during a severely overcast day. It was as if the heavens opened up and angels were singing a song called, “Take The Picture, Already, Dummy”(perhaps you have heard this song yourself). Everything pointed to immediacy.

Full disclosure: getting this shot was not something that stretched me, or demanded exceptional skill. There was not one technically difficult factor in the making of this picture. You yourself have taken pictures like this. They are there and then they’re gone. But, they don’t get collected unless you see how fragile they are, and act in time. It’s not wizardry. It’s just acting on an instinct which, hopefully, gets sharper the longer you are in the game.

I often state one of my only primary commandments for photography as, Always Be Shooting. An important corollary to that rule might be, Always Be Ready To Shoot. Spot the potential in your surroundings quickly. Get used to the fact that many pictures will only dance before you for seconds at a time, flashing like heat lightning, then fading to oblivion. Picture-making is sometimes about casual and careful crafting of an image. And sometimes it’s a race of inches.

And sometimes it’s both.

DON’T EVER ALWAYS DO ANYTHING

This shot, as the one below, is taken at 1/60 sec,, f/2.2, ISO 250, 35mm. The difference between the two images is the white balance setting.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF YOU’VE EVER GLANCED AT THE NORMAL EYE’S HOME PAGE MISSION STATEMENT, you might come away with the impression that I am unilaterally opposed to automodes, those dandy little pre-sets that do their best to predict your needs when making a photo. The truth is that I am against doing anything “all the time”, and thus caution against the universal use of automodes as a way of idiot-proofing your shoots. They can be amazing time-savers, sometimes. They are reliable shortcuts, sometimes. Just like I sometimes like bacon on a burger. There are no universal fixes.

I meet many people who, like myself, prefer to shoot on manual most of the time, eschewing the Auto, Program, Aperture Priority and Shutter Priority modes completely. Oddly, many of these same people almost never take their white balance off its default auto setting, which strikes me as a little odd, since the key to color photography is getting the colors to register as naturally as possible. Auto WB is remarkably good at guessing what whites (and in turn, other hues) ought to look like in a pretty wide variety of situations, but it does make some bad guesses, many of them hard to predict.

A gross-oversimplification of white balance is that it reads the temperature of light from cold to warm. Colder temp light runs bluer. Warmer temp light reads more orange. Auto WB tries to render things as naturally as it can, but your camera also has other customizable WB settings for specific situations, and it’s worth clicking through them to see how easy it is to produce subtle variations.

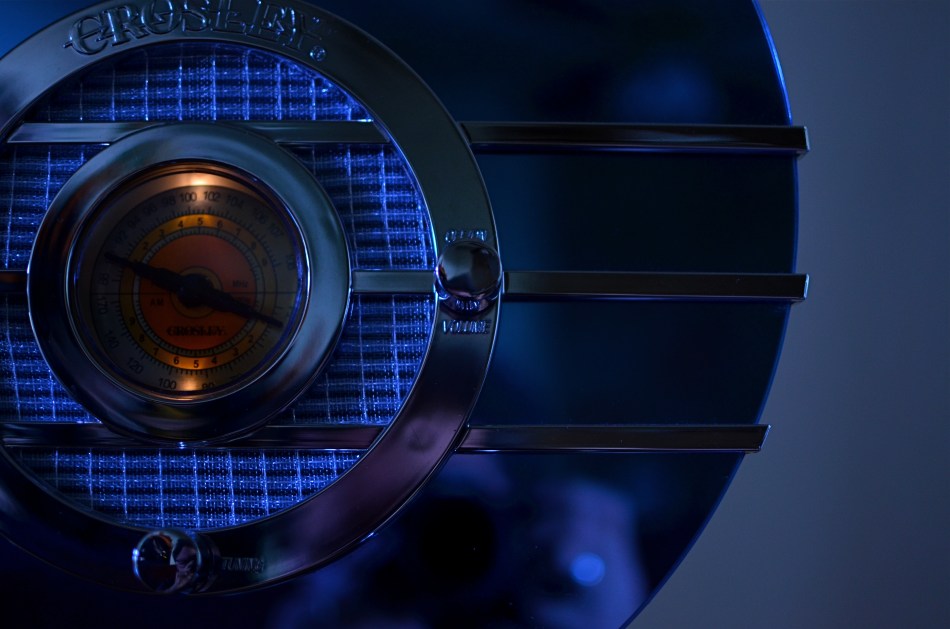

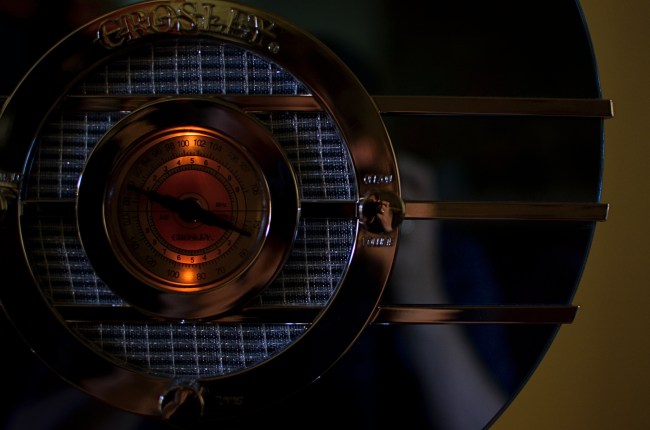

In the picture in the upper left corner, I’m taking a picture indoors, in deep shade, of a reproduction 1930’s Bluebird Sparton radio, a wondrous Art Deco beauty featuring a blue-tinted mirror trimmed in bands of chrome. To emphasize: blue is the dominant color of this item, especially in shade. Shade, being “colder” light, should, in Auto White Balance mode, have registered all that blue just fine, but, in this case, the chrome trim is completely (and unnaturally) painted in the same orange glow. As for the blue values, they’re well, kind of popsicle-y . That’s because, when it’s all said and done, Auto White Balance is your camera’s educated guess, and it sometimes guesses wrong. If you always use it, you will occasionally have to eat a bad picture, unless you take action.

For the above image, I want the dial to be nice and orange, but just the dial. To try to get the blues back to normal on the rest of the radio, I switch to the Tungsten white balance setting (symbolized by a light bulb, since they burn, yes, tungsten filaments), something I normally wouldn’t do in either daylight or shade, but hey, this is an experiment anyway, right? To make it even weirder, Tungsten might read neutrally in some kinds of indoor night settings…but it also doesn’t behave the same way in all cases. In this case, I caught a break: the orange in the radio dial registers pretty true and all the metals are back to shades of silver or blue.

Notice how both white balance settings, in this strange case, both performed counter to the way they are supposed to. One misbehaviour created my problem and another misbehaviour solved it. Hey, that’s show business.

Hence the strange but appropriate title of this post. Don’t ever “always” do…anything. If you want the shot you want (huh?) then pull an intervention and make the camera give it to you. Automode in white balance is just as fraught with risk as any other automatic setting. It works great until it doesn’t. Then you have to step in.

WITHOUT A LEG TO STAND ON

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SHOOTING ON A TRIPOD IS OFTEN RECOMMENDED as the way to afford yourself the most stability in a long exposure. After all, few of us are robotic enough to hold a camera stock-still for anything below a third of a second, so it’s a no-brainer to park your camera on something that’s too inhuman to flinch. You can also take amazing stuff hand-held on shorter night exposures, so long as you (a) have a lens that will shoot around f/1.8 or wider and (b) you can live with the noise a higher ISO will engender.

So, yeah, tripods have their place, but they are not the only determinants in the success of a night-time shoot. And those other x-factors can severely compromise your results. There is the stability of the tripod itself, which isn’t a big sweat if you shelled out $900 for a carbon-fiber Gitzo Pan/Tilt GK, but might generate heartburn if you got something closer to a set of metallic popsicle sticks for $29 at Office Max. The shot above was taken using my own modest (cheap) rig atop Mount Washington across from downtown Pittsburgh, and a few of the healthier gusts threatened to take it and me on a quick lap around the riverfront. Some people buy sandbags. Some believe in the power of prayer. Your choice.

Another x-factor for ‘pod shots is the actual weather you’re shooting in, which will, let’s say, shape your enthusiasm for staying out long enough to get the perfect shot. The smaller your aperture, the longer the exposure. The more long exposures you take, the longer you, yourself, are “exposed”…to snow, sleet, and all that other stuff that mailmen laugh at. Again, referencing the above image, I was contending with freezing drizzle and a windbreaker that was way too thin for heroics. Did I cut my session short? i confess that I did.

I could also mention the nagging catcalls of the other people in my party, who wanted me to, in their profound words, “just take the damned picture” so they could partake of (a)a warm bar, (b) a cold beer, (c) a hot waitress. Result: a less than perfect capture of a fairly good skyline. A little over-exposed, washing out the color. A little mushy, since the selfsame over-exposure allowed the building lights to burn in, rendering them glow-y instead of pin sharp. I was able to fix some of the color deficiencies later, but this is not a “greatest hits” image by any stretch.

Tripods can be lifesavers, but you must learn to maximize their effectiveness just like any other piece of camera equipment. If you’re going to go to a buncha trouble to get a shot, the final result should reflect all that effort, quality-wise.

ABSOLUTES

This image isn’t “about” anything except what it suggests as pure light and shape. But that’s enough. 1/250 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE POPULARLY-HELD VIEW OF THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY makes the claim that, just as video killed the radio star, camera killed the canvas. This creaky old story generally floats the idea that painters, unable to compete with the impeccable recording machinery of the shutter, collectively abandoned realistic treatment of subjects and plunged the world into abstraction. It’s a great fairy tale, but a fairy tale nonetheless.

There just is no way that artists can be regimented into uniformly making the same sharp left turn at the same tick of the clock, and the idea of every dauber on the planet getting the same memo that read, alright guys, time to cede all realism to those camera jerks, after which they all started painting women with both eyes on the same side of their nose. As Theo Kojak used to say, “nevva happennnned…”

History is a little more, er, complex. Photography did indeed diddle about for decades trying to get its literal basics right, from better lenses to faster film to various schemes for lighting and effects. But it wasn’t really that long before shooters realized that their medium could both record and interpret reality, that there was, in fact, no such simple thing as “real” in the first place. Once we got hip to the fact that the camera was both truth teller and fantasy machine, photographers entered just as many quirky doors as did our painterly brothers, from dadaism to abstraction, surrealism to minimalism. And we evolved from amateurs gathering the family on the front lawn to dreamers without limit.

I love literal storytelling when a situation dictates that approach, but I also love pure, absolute arrangements of shape and light that have no story whatever to tell. As wonderful as a literal capture of subjects can be, I never shy away from making an image just because I can’t readily verbalize what it’s “about”. All of us have photos that say something to us, and, sometimes, that has to be enough. We aren’t always one thing or the other. Art can show absolutes, but it can’t be one.

There is always one more question to ask, one more stone to turn.

OPEN ALL NIGHT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHICHEVER SHIFT YOU WORK, YOU ARE FOREVER A STRANGER TO THOSE who work the other side of the workday. And while the majority of us generally fit into the standard 9 to 5 job template, millions of us have our body clocks regularly flipped upside down, our days cloaked in darkness, our brains awake while the city at large sleeps. That means that at any moment, half of us have little comprehension of how the other half lives. There’s a story in that.

And stories need pictures.

Pictorially speaking there has always been a bit of a black market mindset about the night-time, a nether world for some, a regular hangout for others. And with good reason: photography, in its infancy, had to ply its trade largely in sunlight, avoiding scenes which required either too much time, too much prep, or too much patience with slow recording media. But now we live in a very different world, armed with digital computers that look suspiciously(!) like cameras, but which react to light with an efficiency unseen in the entire history of photography.

Capturing the night is no longer a rare technical achievement, and we are really only at the front end of a steadily rising curve of technical enhancement in the area of light sensitivity, with no end in sight. Finally, darkness is something that uniquely colors and reveals reality instead of cloaking it in mystery. There is no longer an end to the shooting day. The image above is by no means an exceptional one, shot with a prime lens open to f/1.8 and a sensor that can deliver manageably low noise even at ISO 1250. More importantly, it is a handheld snap, shot at 1/30 sec…..all but unthinkable just a dozen years ago.

The new golden age of night photography is already apprehended by the youngest generation of shooters, since many of them can’t recall a time when it was a barrier to their expression. And, for those of us longer of tooth and grayer of beard, there is the sensation of being free to wander into areas which used to be sealed off to us. Sun up, sun down, it’s always time to take a picture.

Suddenly your eye is like a great downtown deli.

We’re open all night folks. We never close.

WORKING THE BLINDS

I love this building, but the real star of this image is light; where it hides, bounces, conceals, and reveals.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST CHALLENGING ASPECTS OF URBAN PHOTOGRAPHY, versus shooting in rural settings, is the constant variability of light. On its way to the streets of a dense city, light is refracted, reflected, broken, interrupted, bounced and just plain blocked in ways that sunshine on a meadow can never be. As a result, shooting in cities deals with direct light only intermittently: it’s always light plus, light in spite of, light over here, but not over there. And it’s a challenge for all but the most patient photographers. Almost every frame must be planned somewhat differently from its neighbors, for there can be no “standard” exposure strategy.

I often think of city streets as big window sills sitting below a massive set of venetian blinds, with every slat tilted a little differently. And I personally greet this condition as an opportunity rather than a deficit, since the unique patterns of abstraction mean that even mundane scenes can be draped in drama at any given moment. That’s why, as I age, I’ve come to highly value selective lighting, for mood, since I’m convinced that perfectly even lighting on an object can severely limit that selfsame drama.

I’m also reminded of the old Dutch masters painters, who realized that a partially dark face contains a kind of mystery. Conversely, a street scene that contains no dropouts of detail or light makes everything register just about the same with the eye, and can keep your images from having a prominent point of interest. Darkness, by contrast, asks your imagination to supply what’s missing. Even light is a kind of full disclosure, and it can rob your pictures of their main argument, or the “look over here” cue that’s needed to make a photograph really connect.

Back to street photography. Given that glass and metal surfaces, the main ingredients in urban structures, can run a little to silver and blue, I may actually take an unevenly lit scene and either modify it toward those colors with a filter, or simply under-expose by a half-stop to see how much extra mood I can wring out of the situation, as in the above image of an atrium in midtown Manhattan. Think of it as “working” those big venetian blinds. Cities both reveal and conceal, and your images, based on your approach, can serve both those ends.

TECHNIQUE OR STYLE?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YEARS OF WRITING DAILY HUMOR MATERIAL FOR OTHERS IN THE RADIO RACKET taught me that comedians fall into two general camps: those who say funny things and those who say things funny. Depending on how you rate writing, your own independence, or even your career longevity, you may opt to be in the first group, flawlessly executing pre-written material, or the second, where the manner in which you put things across allows you to get laughs reading the phone book.

I make this distinction between technique (the gag reciter) and style (the ability to imbue anything with comedy) because photographers must face the exact same choices. Technique helps us deliver the goods with technical precision, to master steps and procedures to correctly execute, say, a time exposure. Style is the ability to stamp our vision on nearly anything we see; it’s not about technical mastery, but internal development. Two different paths. Very different approaches to making pictures.

Obviously, great shooters can’t put their foot exclusively in either camp. Without technique, your work has no level standards or parameters. Lighting, exposure, composition….they all require skills that are as basic as a driver’s-ed class. However, if you merely learn how to do stuff, without having a guiding principle of how to harness those skills, your work will be devoid of a certain soul. Adept but not adorable. This is a trap I frequently find myself falling into, as my shots are a little technique heavy. Result: images that are scientifically sound but maybe a trifle soul-starved. Yeah, I could make this picture, but why did I?

On the style side, of course, you need fancy, whimsy, guts, and, yes, guesswork to produce a masterpiece. However, with an overabundance of unchanneled creativity, your work can become chaotic. Your narrative ability may not be up to the speed of your “vision”, or you may simply lack the wizardry to capture what your eye is seeing. Photographers are, more than anything else, storytellers. If they fail in either grammar or imagination, the whole thing is noise.

Like comics, photographers are both technicians and artists. Even the most seasoned among us needs a touch o’ the geek and a touch of the poet. Anything else is low comedy.

GRABBING THE GLOW

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY PHOTOGRAPH YOU TAKE IS OF CONSEQUENCE.

That doesn’t mean that every subject you shoot will “matter”, or that every mood you capture will be important. Far from it. However, every frame you shoot will yield the most positive thing you could hope for in your development. Feedback. This worked. God, this didn’t. Try again with more of this. One more time, but change the angle. The light. The approach. The objective. Nothing that you shoot is time wasted, since the positive and negative information gleaned is all building toward your next ah-ha miracle.

Your greatest work has to come as the total of all the building blocks of all the little details you teach yourself to sweat. And that is why you must, I repeat with religious fervor, Always Be Shooting. Something from a photo that won’t change the world will wind up in the photo that will. The what-the-heck experiment of today’s shot is the foundational bedrock of tomorrow’s. You are always going to be your most important teacher, and you get better faster by giving your muscles lots of exercise.

Your greatest work has to come as the total of all the building blocks of all the little details you teach yourself to sweat. And that is why you must, I repeat with religious fervor, Always Be Shooting. Something from a photo that won’t change the world will wind up in the photo that will. The what-the-heck experiment of today’s shot is the foundational bedrock of tomorrow’s. You are always going to be your most important teacher, and you get better faster by giving your muscles lots of exercise.

Light changes, those hundreds of shadows, flickers, hot spots and glows that appear around your house for minutes at a time during every day, are the easiest, fastest way to try something…anything. A window throws a stray ray onto your floor for three minutes. Stick something in it and shoot it. A cloud shifts and bathes your living room in gold for thirty seconds. Place a subject in there to see how the light plays over its contours. Shoot it, move it, shoot it again. Lather, rinse, repeat.

The image at left came when a shaft of late afternoon light shot through my bathroom window for about three minutes. I grabbed the first thing I saw that looked interesting, framed it up, and shot it. Learned a little about shadows in the process. Nothing that will change the world. Still.

Many cheap, simple opportunities for learning get dumped in your lap everyday. Don’t wait for masterpiece subject matter or miracle light. Get incrementally better shooting with what you have on hand. Grab the little glows, and use spare minutes to see what they can do to your pictures. And, on the day when the miracle saunters by, you will be ready.

FINDING AN OPENING

Walking briskly down a city street with wildly varying light conditions, you might not want to stop to fully calculate manual exposure before every shot. In such cases, Aperture Priority may be good fit.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I KNOW THAT I APPROACH THE IDEA OF SHOOTING ON MANUAL with what must strike some as evangelistic zeal. We’re talking full-on-John-The-Baptist-mad-prophet mode. I do so because I believe that, the further you can go toward overseeing every single facet of your picture taking, that is, the less you delegate to a machine that can’t think, the better. Generally. Most of the time. Almost always.

Except sometimes.

Aperture Priority, the mode that I most agree with after pure manual, can be very valuable in specific conditions, for very specific reasons. In AP (Av for Canon folks), you dial in the aperture you want for everything you’re about to shoot, depending on what depth-of-field you want as a constant. Then it’s the camera’s job to work around you, adjusting the shutter speed to more or less guarantee a proper exposure. Let me interject here that there are millions of great photographers who nearly live on the AP setting, and, like any other strategy, you have to decide whether it will deliver the goods as you define them.

If you are “running and gunning”, that is, shooting a lot of frames quickly, where your light conditions, shot-to-shot, will be changing a great deal, Aperture Priority might keep you from tearing out your hair by eliminating the extra time you’d spend custom-calculating shutter speed in full manual mode. Fashion, news and sports situations are obviously instances where you need to be fully mindful of your composition, cases in which those extra fragments of “figgerin'” time in between clicks might make you miss an opportunity. And no one will have to tell you when you’re in such a situation.

Conversely, if you are shooting more or less at leisure, with time to strategize in-between shots, or with uniform light conditions from one frame to the next, then full manual may work for you. I have shot in manual for so many years that, in all but the most hectic conditions (cattle stampede or worse), I’m fast enough to get what I want even with calculation time factored in. But it doesn’t matter what works for me, does it, since I won’t be taking your pictures (pause here to thank your lucky stars). If you need one less task to hassle with, and AP gives you that one extra smidge of comfort, mazel tov.

One other thing to note about Aperture Priority: it’s not foolproof. Change your central focal spot to different objects within the same composition (say from a tree to the rock next to the tree) snap several frames, and the exposure could be vastly different on each image. Could that happen when you’re on manual? Certainly. You can, of course, fiddle with exposure compensation on AP, essentially overruling the camera, but, to take the time for all that, you’re really not saving much more time than shooting manual anyway. See what you can live with and go.

This blog is a forum, not the Ten Commandments, so I never want to profess that my way is the only way, whether it’s taking photographs or deciding what toppings should go on pizzas. Although, let’s face it, people who put pineapple on them….that’s just warped, am I right?

A GAME OF INCHES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS PROGRESS FROM WHAT I CALL SNAPSHOT MENTALITY TO “CONTACT SHEET” MENTALITY as we move from eager beginners to seasoned shooters. Many of the transitional behaviors are familiar: we actually learn what our cameras can do, we begin to pre-visualize shots, we avoid 9 out of the 10 most common errors, etc. However, one of the vestiges of snapshot mentality that lingers a while is the tendency to “settle”, to be, in effect, grateful that our snap resulted in any kind of a shot, then moving too quickly on to the next subject. It’s a little like marrying the first boy that ever asked you out, and it can prevent your hanging around long enough to go beyond getting “a” shot to land “the” shot.

In snapshot mentality, we’re grateful we got anything. Oh, good, it came out. In contact sheet mentality, we look for as many ways to visualize something as possible, like the film guys who shot ten rolls to get three pictures, seeing all their possibilities laid side-by-side on a contact sheet. The film guys stood in the batter’s box long enough to make a home run out one of all those pitched balls. With the snapshot guy, however, it’s make-or-break on a single take. I don’t like the odds. My corollary to the adage always be shooting would be always shoot more.

All of which is to plead with you to please, please over-shoot, especially with dynamic light conditions that can change dramatically from second to second. In the shot at the top, I was contending with speedily rolling overcast, the kind of sun-clouds-sun rotation that happens when a brief rain shower rolls through. My story was simply: it’s early morning and it just rained. This first shot got these basics across, and, if I were thinking like a snapshot photographer, I would have rejoiced that I nailed the composition and quit while I was ahead. However, something told me to wait, and sure enough, a brighter patch of sunshine, just a minute later, gave me a color boost that popped the page much more effectively. Same settings, same composition. The one variable: the patience to play what is, for shooters, a game of inches. A small difference. But a difference, nonetheless.

And that’s what these little blurbs are. Not examples of groundbreaking art, just illustrations of the different ways to approach a problem. Digital shooting is cheap shooting, nearly free most of the time. Shouldn’t we, then, give ourselves at least as many editing choices as film guys who shot rolls of “maybes” at great expense, in search of their “yeses”? Hmm?

THE FAULT IN OUR DEFAULT

Potential nightmare: uneven light and wildly varied contrast. But I can save this shot because I can take direct control of camera settings.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CHILDREN THINK THAT HAPPINESS RESIDES IN ALWAYS BEING TOLD “YES”. Of course anyone who has ever (a) been a child or (b) had to deal with one knows that this is actually the worst of strategies. Even without being Tiger Moms, we can all pretty much agree that there are many times when telling a kid “NO” will improve, perhaps even save, his life. Negative responses carry important information. They can be guidelines. Most importantly, they convey that there are limits, consequences.

“NO” also helps you be a better photographer.

In the ’60’s, one of the most basic cameras ever sold, the teen-marketed Polaroid Swinger, had a shutter that you pinched to check if you had enough light to make a picture. If the word “YES” appeared in the viewfinder, you were solid. “NO”, given the simplicity of the gadget, meant, sorry, point this thing somewhere toward, you know, actual light. Easy. Unmistakable. Take the picture with a “NO”, and it’s on you.

Similar light conditions to the scene shown above, but now the phone camera has decided for me, to jack up the ISO, degrading the image. And there wasn’t a thing I could do to prevent it.

DSLR’s still flash a similar warning. With Nikon it’s “subject is too dark”. But the camera isn’t a mean parent that won’t let you choose ice cream over asparagus. It’s being a good parent that’s trying to give you a happy outcome. By contrast, smartphone cameras are bad parents. They never tell you “no”. If anything, their attitude is, point anywhere you like, anytime you like, darling. Mommy will still make a picture for you. That’s because the emphasis of design and use for smartphones is: make it simple, give the customer some kind of result, no matter what. You push the button, sweetheart, and we’ll worry about all that icky science stuff and give you a picture (image at left).

The default function of smartphone cameras is wondrous. You get a picture, every damn time. Never a blank screen, never a “no”. But in low-light situations, to accomplish this, the camera has to jack up the ISO to such a ridiculous degree that noise goes nuclear and detail goes buh-bye. The device has been engineered to make you happy over everything else, and its marketers have determined that you’d rather have a technically flawed picture than no picture, so that’s the mission. And that guarantees that your photography will linger in Average-land pretty much forever.

With iPhones, you have no override. You have no thumbs-up-thumbs-down decision. You have, actually, no input at all except your choice of subject and composing style. Now, you may think that this “frees” you, with the camera “getting out of your way”, and all, but it really means that, even if you have a better idea for making an image than your camera does, you cannot act upon it. Cameras that say “NO” are also saying, “but if you try something else, you will get to “YES” (image at top). Cameras that only say “YES” are really saying, “I know best. Leave it to me.”

Which of course, is something you heard all the time, years ago.

When you were a child.

DISTINCTION WITHOUT A DIFFERENCE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY IS ONLY PARTLY ABOUT A STRING OF TECHNICAL DEVELOPMENTS AND BREAKTHROUGHS. It is also the chronicle of what those advances have done to democratize the art, moving it from the domain of rich tinkerers and elites to an arena in which nearly anyone can participate and compete. From the first box camera to Instagram, it is about breaking down barriers. This is not something that is open to debate. It just is.

That’s why it’s time to re-think the words professional and amateur as they apply to the making of images. This is the kind of topic where everybody tends to throw down passionately on one side or the other, with few straddlers or fence-sitters.

Those shooters whose toil is literally their bread and butter are, understandably, a little resentful of the newbie whose low-fi snap of a trending topic tops a million likes on Twitter, all without said snapper’s having mastered the technical ten commandments of exposure or composition. And those whose work is honest, earnest and sincere, yet formally uncertified, hate being thought of as less Authentic, Genuine, or Real simply because no one has printed their output in the approved channels of accepted craft, be it magazines like Nat Geo or the cover of the New York Times.

Okay, I get it. From your personal perspective, you don’t get no respect. But you know what? Get over yourself.

Do we really need to trot out the names of those who never got paid a penny for their work, mostly because their entire output consisted of inane selfies or dramatic lo-fi still lifes of their latest latte? Is it helpful to point out the people within the “official” photographic brotherhood whose work is lazy or derivative? Nope. It is beyond pointless for the two sides to get into an endless loop of So’s Your Mom.

So let’s go another way.

The words professional and amateur are, increasingly, distinctions without difference, at least as ways to attest to the quality of the end product: the photograph. When you pick up a magazine featuring a compelling image, do you ever, ever ask yourself whether it was taken by someone who got paid for it, or do you, in fact, either react to it or ignore it based on its power, its emotional impact, the curiosity and daring of the shooter? The fact is, photography has, from day one, been moved forward by both hobbyist and expert, and, in today’s world, the only thing that makes a shot “professional” is the talent and passion with which it’s been rendered. Anything else is just jaw music.

MAGICAL ORPHANS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WE HAVE ALL EXPERIENCED THE SHOCK OF SEEING OURSELVES IN A CERTAIN KIND OF PHOTOGRAPH, a strange combination of framing, light or even history that makes us actually ask, “who is that?? before realizing the truth. Of course we always know, intellectually, that a photo is not an actual visual record of events but an abstraction, and still we find ourselves emotionally shocked when it’s capable of rendering very familiar things as mysteries. That odd gulf between what we know, and what we can get an image to show, is always exciting, and, occasionally, confounding.

Every once in a while, what comes out in a picture is so jarringly distant from what I envisioned that I want to doubt that I was even involved in capturing it. Such photographs are magical orphans, in that they are neither successes nor failures, neither correct or wrong, just…..some other thing. My first reaction to many of these kinds of shots is to toss them into the “reject” pile, as every photo editor before 1960 might have, but there are times when they will not be silenced, and I find myself giving them several additional looks, sometimes unable to make any final decision about them at all.

The above shot was taken on a day when I was really shooting for effect, as I was using both a polarizing filter to cut glare and a red 25 filter to render severe contrast in black and white. The scene was a reedy brook that I had shot plenty of times at Phoenix’ Desert Botanical Garden, but the shot was not planned in any way. As a matter of fact, I made the image in about a moment and a half, trying to snap just the shoreline before a boisterous little girl could get away from her parents and run into the frame. That’s all the forethought that went into it.

With all the extreme filtration up front of the lens, I was shooting slow, at about 1/30 of a second, and, eager to get to the pond, the child was just too fast for me. Not fast enough to be a total blur, but fast enough for my lens to render her softly, strangely. And since every element in a picture talks to every other element, the rendering of the reeds, which was rather murky, added even more strangeness to the little girl, her face forever turned away, her intent or presence destined to remain a secret.

I might like this picture, but I worry that wanting to like it is making me see something in it that isn’t there. Am I trying to wish some special quality into a simple botched shot, acting as a sort of self-indulgent curator in search of “art”?

Can’t tell. Too soon.

Check with me in another five years or so.