EQUATIONS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY CHANGE YOU MAKE IN THE CREATION OF A PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGE also changes every other element of the picture.

You can’t alter a single element in a photo in isolation. Each decision you make is a separate gear, with its own distinctive teeth, and the way those teeth mesh with all the other gears in the photographic equation determines success in the final picture.

As an example, let’s look at sharpness, perhaps the big “desirable” in an image. The term sounds simple, but is, in fact determined by an entire raft of factors, among them:

A) Choice Of Lens. How uniform is the sharpness of your glass? Is it softer at the edges? Completely sharp at smaller apertures? Does it deliver amazing pictures at one setting while causing distortions or inaccuracies at another?

B) Aperture. The most basic predictor of sharpness, whether you scrimped or splurged on Item “A”.

C) Choice Of Autofocus Setting. Are you telling your camera to selectively sharpen a key object in an isolated part of your image, or asking it to provide uniform sharpness across the entire frame?

D) Anti-vibration. On some longer exposures (for example, on a tripod) this feature may actually be costing you sharpness. Protecting your shot against the hand-held shakes is good. Confusing a camera with active Anti-vibe on a stabilized shot may not work out as well.

E) Contrast. Some people believe that the sharpness of lines and textures is actually the viewable distance between light and darkness, that contrast is “sharpness”. Based on what you prefer, other big choices can be affected, such as the decision to shoot in color or black and white.

F) Stability. Deals with everything from how steady you grip a camera to what else besides yourself, from shutter triggering to SLR mirror shifting, can cause measurable vibration, and thus less sharpness.

G) Editing/Processing. This is where miracles occur. Sometimes. Other times, it’s where we try to slap lipstick on a pig.

We could go on, and so could you. And then consider that this quick checklist only deals with sharpness, just a single element, which, in turn, affects every other aspect of your pictures. Photography is a constant juggling act between technique, experience, experiment, and instinct. What you want to show in your images will dictate how much (or how well) you keep all those balls aloft.

THE FLEXIBLE FREEZE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS ACROSS THE LAST TWO CENTURIES HAVE CAPITALIZED ON ONE OF THEIR MEDIUM’S BEST TRICKS, the ability to freeze time, the sensation of carving out micro-seconds of reality and preserving them, like ancient scarabs trapped in amber. The thing known as “now”, with the aid of the camera, became something called “forever”, as things which were, by nature, fleeting were granted a kind of immortality. Events became exhibits, things to be studied or re-lived at our whim.

And yet, even as we extract these frozen moments, we mess around the edge of the illusion a bit, making still pictures also convey a sense of motion. Focus is a prime example of this retro-fitting of technique. No sooner had photography evolved the technical means to render sharp images than shooters began to put a little soft imprecision back into their pictures, by a variety of means: slow shutter speeds, time exposures, manual shaking, delayed flashes, and selective focus. Of all these techniques, at least for me, selective focus has proven to be the hardest to master.

….and two more lattes, 2016, shots on a Lensbaby Composer Pro, which allows a sweet spot of sharp focus to be moved anywhere in the frame the shooter desires.

Changing the messaging of a photographic story by using focus to isolate some elements and downplay others has always called for real practical knowledge of the workings of lenses and how they create focus as an effect. Recently, digital manipulation has allowed shooters to re-order the focal priorities of a shot after it’s taken, and in just the past few years, commercially available specialty lenses have allowed photographers to pre-select where and when focus will occur in an image, using it as interpretively as color or exposure.

I like to use the Lensbaby family of variable-focus lenses for what I call “flexible freeze” situations, times when focus can be massaged to create the illusion of speed. In the above shot, taken in a high-volume cafe, the small center of tight focus fans out to a near streaky quality at the outer edges of the picture. No one person is rendered sharp enough for features to register, or matter. What’s important here is the sensation of a busy lunch rush, which actually would be diminished if everything was in uniform focus.

Sharpness is certainly desirable in most cases for a strict re-creation of literal reality, but photography has never merely been a recording process. Focus can produce useful abstractions or atmospheres in a shot, so long as the effect serves the story. If it doesn’t help the image speak better, even a flexible freeze can quickly become a tiresome gimmick. Matching tools to goals is what good photography does best.

INSTANT VELVET

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE WERE, IN THE DAYS OF FILM, two main ways to create the velvety glow of uniformly soft focus so prized by portrait subjects. The more expensive route lay in purchasing a dedicated portrait lens that achieved more or less of the effect, depending mainly on aperture. The other, cheaper way was to screw-on a softening filter, making any lens adaptable to the look. Now, in the digital era, those two options have been joined by softening apps for phone cameras and in-camera “filters”, which add the effect after the photograph has been snapped.

That’s the beauty of where we are in the history of photography, where every problem has a half-dozen different solutions, offered at different levels of complexity, ease, and affordability. In the golden days of Hollywood, cinematographers achieved the soft look with some Vaseline smeared over the lens, or by attaching different gauges of gauze to the glass. Both tricks made yesterday’s matinee idols look like today’s ingenues, and now, anyone with a reasonably sophisticated camera can achieve the same success with half the bother.

I myself prefer to shoot soft focus “live”, that is, in the moment, with either a dedicated lens or a filter, but you aren’t always in the same frame of mind when you shoot something as when you review it later. In-camera processing, while offering less fine control (tweaking pictures that have already been shot), can at least give you another comparative “version” of your image at literally no trouble or cost. With Nikon, you simply select the “Retouch” menu, dial down to “Filters”, select “Soft” and scroll to the image you want to modify. For Canon cameras, go to the “Playback” menu, select “Creative Filters”, scroll to “Soft” and pick your pic. The image at left shows the result of Nikon’s retouch filter, applied to the above picture.

One personal note: I have tried several phone app softeners as post-click fixes, and find that they generally degrade the quality of the original image, almost as if you were viewing the shot through a soup strainer. Your mileage may vary, but for my money, the app versions of soft focus are not ready for prime time yet. Best news is, the soft-focus effect is so popular that eventually all solutions will be generally equal, regardless of platform, since the marketplace always works in favor of the greatest number of people making pictures. Always has, always will.

All things considered, we got it pretty soft.

RAZOR’S EDGE

Sharpness should be achieved in your intial shot by use of contrast and color, not “dialed up” in post-editing. 1/160 sec., f/8, ISO 100, 22mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE AVAILABILITY OF PHOTO PROCESSING TOOLS, TO ARTIST AND BEGINNER ALIKE, in the digital era, has created a kind of unfortunate slingshot effect, as all suddenly achieved freedoms tend to. Once it became possible for Everyman to tweak images in a way that was once exclusively the province of the professional, there followed a trend toward twisting every dial in the tool box to, let’s be honest, rescue a lot of marginal shots. Raise your hand if you’ve ever tried to glam up a dud. Now raise your hand if you inadvertently made a bad picture worse by slathering on the tech goo.

Welcome to the phenomenon known as over-correction.

It’s human nature, really. Look at Hollywood. Suddenly freed from the confines of the old motion picture production code in the 1960’s, directors, understandably, took a few years to make up for decades of artistic construction by pumping out a nude scene and/or a gore fest in everything from romantic comedies to Pink Panther cartoons. Several seasons of adolescent X-rated frolics later, movies settled down to a new normal. The over-correction gave way to a more mature, even restrained style of film making.

Am I joining the ranks of anti-Photoshop trolls? Not exactly, but I am noting that, as we grow as photographers, we will put more energy into planning the best picture (all energy centered before the snap of the shutter), and less energy into “fixing it in post”. If you shoot long enough and work hard enough, that shift will just happen. More correctly designed in-camera images equals fewer pix that need to be dredged from Dudland.

Look at the simple idea of sharpening. That slithery slider is available to everyone, and we all race after it like a kid chasing the Good Humor truck. And yet, it is a wider range of color and contrast, which we can totally control in the picture-taking process, which will result in more natural sharpness than the Slider Of Joy can even dream of. As a matter of fact, test my argument with your own shots. Increase your control of contrast or color and see if it doesn’t help wean you off the sharpen tool. Or expose your shots more carefully in-camera rather than removing shadows and rolling off highlights later. Or any other experiment. Your goals, your homework.

The point being that more mindful picture-making will eliminate the need for many crutch-like editing tweaks after the fact. And if that also makes you a better shooter overall, isn’t that pretty much the quest?

BE THE CAMERA. NOW BE BETTER THAN THAT.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MERELY INVOKING THE NAME OF ANSEL ADAMS is enough to summon forth various hosannas and hallelujahs from anyone from amateur shutterbug to world-renowned photog. He is the saint of saints, the yardstick of yardsticks. He is the photographer was all want to be when (and if) we grow up. His technical prowess is held as the standard for diligence, patience, vision. And yet, even at the moment we revere Adams for his painstaking development of the zone system and his mind-blowing detail, we are still short-changing his greatest achievement.

And it is an achievement that many of us can actually aspire to.

What Ansel Adams did, over a lifetime, was work his equipment way beyond its limits, milking about 2000% out of every lens, camera and film roll, showing us that, to make photographs, we have to constantly reach beyond what we think is possible. Given the slow speed of much of the film stocks and lenses of his era, he, out of the wellspring of his own ingenuity, had to make up the deficit. He had to be smarter, better than his gear. No one piece of equipment could give him everything, so he learned over a lifetime how to anticipate every need. Look at one of many lists he made of things that he might need on a major shoot:

Cameras: One 8 x 10 view camera with 20 film holders and four lenses; 1 Cooke Convertible, 1 ten-inch Wide Field Ektar, 1 nine-inch Dagor, one six and three-quarters-inch Wollensak wide angle. One 7 x 17 special panorama camera with a Protar 13-1/2-inch lens and five holders. One 4 x 5 view camera with six lenses; a twelve-inch Collinear, including an eight-and-a-half Apo Lentar, a nine-and-a-quarter Apo Tessar, 4-inch Wide Field Ektar, Dallmeyer telephoto. One Hasselblad camera outfit with 38, 60, 80, 135, & 200 millimeter lenses. A Koniflex 35 millimeter camera. Two Polaroid cameras. 3 exposure meters (one SEI, two Westons).

Extras: filters for each camera: K1, K2, minus blue, G, X1, A, C5 &B, F, 85B, 85C, light balancing, series 81 and 82. Two tripods: one light, one heavy. Lens brush, stopwatch, level, thermometer, focusing magnifier, focusing cloth, hyperlight strobe portrait outfit, 200 feet of cable, special storage box for film.

Transport: One ancient, eight-passenger Cadillac station wagon with 5 x 9-foot camera platform on top.

However, the magic of Ansel Adams’ work is not in how much equipment he packed. It’s that he knew precisely what tool he needed for every single eventuality. He likewise knew how to tweak gear to its limits and beyond. Most importantly, his exacting command of the elemental science behind photography, which most of us now use with little or no thought, meant that he took complete responsibility for everything he created, from pre-visualization to final print.

And that is what we can actually emulate from the great man, that total approach, that complete immersion. If we use all of ourselves in every picture that we make, we can always be better than our cameras. And, for the sake of our art, we need to be.

PRECISION C, FEELING A

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF YOU TRAVEL ENOUGH, YOU’LL DISCOVER THAT, OF ALL THE TIMES YOU WANT to take a photograph, there are only a few times in which acceptable picture-making conditions are actually present. For all too many subjects that you experience on the fly, only a small percentage of them allow you the time, light, information or opportunity to do your best. And yet…you do what you must, and trust to instinct and chance for the rest.

Immediately upon arrival in a new town, my mind goes to one task, and one task only: sticking anyone else with the driving, so I can take potshots out the car window as I see fit. I have no need to head the posse or lead the expedition. You be in charge, big man. Get me to the hotel and leave me to make as many attempts as possible to put something worthwhile inside my camera.

Of course, this means that I have to pay at least some attention to how insanely you drive…shortcuts, rapid swerves, jolts and all. And, hey, couldn’t you have lingered a millisecond longer after the light went green, since I was just about to create an immortal piece of street art, instead of the muscular spasm I now have frozen forever on my memory card?

When shooting from a car, there are lots of things that go out the window (sorry), among them composition, exposure, stability, and, most generally, focus. En route to L’Enfant Plaza in Washington D.C. a few years ago, I fell in love with the funky little tobacco shop you see here. The colors, the woodwork, the look of yesteryear, it all spoke to me, and I had to have it. So I shot it at 1/250 sec, more than fast enough to freeze nearly anything in focus, unless by “nearly anything” you mean something that you’re not careening past at the pace of the average Tijuana taxicab. Result? Well, I didn’t wind up with unspeakable blur, but it’s certainly softer than I wanted. Of course, I could have offered an acceptable alibi for the shot, something based on some variant like, “of course, I meant to do that”, that is, until I outed myself in this post, just now.

But we try. Sometimes it’s the fleeting nature of things seen from car windows that make the attempt even more appealing than the potential result. In that instant, it seems like nothing’s more important than trying to take a picture. That picture. I won’t get ’em all. But as long as I live, I hope I never lose that mad, what-the-hell urge to just go for it.

So okay, seeing as this is a photo of a tobacco shop, this is where one of you cashes in the “close, but no cigar” gag line.

Go ahead, I’ll give you that one.

DETAILS, DETAILS

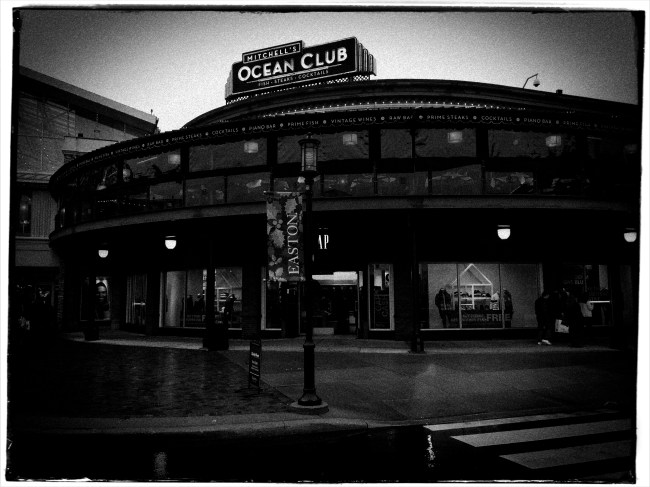

Moody, but still a bit too tidy. Black and white by itself wasn’t enough to create the atmosphere I wanted.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVEN THOUGH MOST GREAT PHOTOGRAPHERS PROCLAIM that any “rules” in their medium exist only to be broken, it’s often tough to chuck out regulations that have served you well over a lifetime of work. Once you get used to producing decent images through the repetition of habit, it takes extra nerve to take yourself outside your comfort zone, even if it means adding impact to your shots. You tend not to think of rules as arbitrary or confining, but as structural pillars that keep the roof from falling in.

That’s why it’s a good exercise to force yourself to do something that you feel is a bad fit for your style, lest your approach to everything go from being solid to, well, fossilized. If you hate black and white, make yourself shoot only monochrome for a week. If you feel cramped by square framing, make yourself work exclusively in that compositional format, as if your camera were incapable of landscape or portrait orientations. In my own case, I have to pry my brain away from an instinctual reliance on pinsharp focus, something which part of me fears will lead to chaos in my images. However, as I occasionally force myself to admit, sharp ain’t everything, and there may even be some times when it will kill, or at least dull, a picture.

With post-processing such an instantaneous, cheap, and largely effortless option these days, there really isn’t any reason to not at least try various modes of partial focus just to see where it will lead. Take what you believe will work in terms of the original shot, and experiment with alternate ways of interpreting what you started with.

In the shot at the top of this post, I tried to create mood in a uniquely shaped fish house with monochrome and a dour exposure on a nearly colorless day. Thing is, the image carried too much detail to be effectively atmospheric. The place still looked like a fairly new, fairly spiffy eatery located in an open-air shopping district. I wanted it to look like a worn, weathered joint, a marginal hangout that haunted the wharf that its seafood theme and design suggested. I needed to add more mood and mystery to it, and merely shooting in black & white wasn’t going to get me there, so I ran the shot through an app that created a tilt-shift focus effect, localizing the sharpness to the rooftop sign only and letting the rest of the structure melt into murk.

It shouldn’t be hard to skate around a rule in search of an image that comes closer to what you see in your mind, and yet it can require a leap of faith. Hard to say why trying new things spikes the blood pressure. We’re not heart surgeons, after all, and no one dies if we make a mistake.Anyway, you are never more than one click away from your next best picture.

LEFTOVERS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FAR BE IT FROM ME TO DO A HATER NUMBER on photographic post-processing. We often pretend that the act of photo manipulation began at the dawn of the pixel age, when, of course, people have been futzing with their images since the first shutter snapped. We love the idea of “straight out of the camera” as an ideal, but it’s just that…an ideal. Eventually, it’s the way processing is executed in a specific instance which either justifies or condemns its use.

With that in mind, I do find that too many of us use faux b&w, or the desaturation of color images, long after they’re snapped, as a kind of last-ditch attempt to save pictures that didn’t have enough force or impact in the first place. Have I resorted to this myself? Oh, well, yeah, maybe. Which means, freaking certainly. Have I managed to “save” many images in this way? Not so much. Usually, I feel like I’m serving leftovers and trying to pawn them off as a fresh meal.

Up In Your Grille, 2015. A mere b&w conversion from color would have flattened out many of this image’s tones.

The further along I lope through life, however,the more I tend to believe that the best way to make a black and white image is to set out to intentionally do just that. An act of planning, pre-visualization, deliberation. It means looking at your subject in terms of how a color object will register over the entire tonal range of greys and whites. Also, texture, as it is accentuated by light, is particularly powerful in monochrome, so that part needs to be planned as well. Exposure, as it’s effected by polarizers or colored filters also must be planned, as values in sky, stone or foliage must be anticipated. And, always, there is the use of contrast as drama, something black and white does to great effect.

You might be able to convert a color shot into an even more appealing b&w shot in your kerputer, but the most direct route, that is, making monochrome in the moment, is still the best, since it gives you so many more options while you’re managing every other aspect of the shot in real time. It all comes down to a major philosophical point about photography, which is that the more control you can wield ahead of the click, especially with today’s shoot-it-check-it-shoot-it-again technology, the better your results will be.

THE CHOICE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ANYONE WHO REGULARLY VISITS THESE PAGES already knows that I advocate of doing as much of your photography in as personal and direct a way as possible. While I am completely astonished by the number of convenience items and automatic settings offered to the casual photographer in today’s cameras, I believe that many of these same features can also delay the process by which people take true hands-on control of their image-making. I regard anything that gets in between the shooter and the shutter as a potential distraction, even a drag on one’s evolution.

Tools are not technique. Here are two parallel truths of photography: (1) some people with every gizmo in the toy store take lousy pictures. (2) some people with no technical options whatsoever create pictures that stun the world.

From my view, you can either subscribe to the statement, “I can’t believe what this camera can do!” or to one which says, “I wonder what I can make my camera do for me!” The very controls built into cameras to make things convenient for newcomers are the first things that must be abandoned once you are ready to move beyond newcomer status. At some point, you learn that there is no way any camera can ever contain enough magic buttons to give you uniformly excellent results without your active participation. You simply cannot engineer a device that will always deliver perfection and perpetually protect you from your own human limits.

Innovators never innovate by surrounding themselves with the comfortable and the familiar. For photographers, that means making decisions with your pictures and living with the uneven results in the name of self-improvement. This is a challenge because manufacturers seductively argue that such decisions can be made painlessly by the camera acting alone. But guess what. If you don’t actively care about your photos, no one else will either. There may not be anything technically wrong with your camera’s “choices”. But they are not your choices, and eventually, you will want more. The structure that at first made you feel safe will, in time, start to feel more like a cage.

Tools are not technique.

THE BOY IN THE BALL CAP

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MORE SHOTS, MORE CHOICES: Photography really is as simple as that. The point has been hammered home by expert and amateur alike since before we could say “Kodak moment”: over-shooting, snapping more coverage from more vantage points, results in a wider ranger of results, which, editorially, can lead to finding that one bit of micro-mood, that miraculous mixture of factors that really does nail the assignment. Editors traditionally know this, and send staffers out to shoot 120 exposures to get four that are worthy of publication. It really, ofttimes, is a numbers game.

For those of us down here in the foot soldier ranks, it’s rare to see instances of creative over-shoot. We step up to the mountain or monument, and wham, bam, there’s your picture. We tend to shoot visual souvenirs: see, I was there, too. Fortunately, one of the times we do shoot dozens upon dozens of frames is in the chronicling of our families, especially the day-to-day development of our children. And that’s vital, since, unlike the unchanging national monument we record on holiday, a child’s face, especially in its earlier years, is a very dynamic subject, revealing vastly different features literally from frame to frame. As a result, we are left with a greater selection of editing choices after those faces dissolve into other faces, after which they are gone in a thrilling and heartbreaking way.

One humbling thing about shooting kids is that, after they have been around a while, you realize that you might have caught something essential, months or years ago, during an event at which you just felt like you were reacting, racing to catch your quarry, get him/her in focus, etc. A feeling of always trying to catch up. It’s one of the only times in our own lives that we shoot like paparazzi. This might be something, better get it. I’ll sort it out later. The process is so frenetic that some images may only reveal their gold several miles down the road.

Not the sharpest image I ever shot, but look at that face. Slow shutter to compensate for the dim light. 1/40 sec., f/3.2, ISO 200, 35mm.

My grandson is now entering kindergarten. He’s reading. He’s a compact miniature of his eventual, total self. And, in recently riffing through images of him from early five years ago (and yes, I was sniffling), I found an image where he literally previews the person I now know him to be. This image was always one of my favorite pictures of him, but it is more so now. In it, I see his studious, serious nature, and his intense focus, along with his divine vulnerability and innocence. Technically, the shot is far from perfect, as I was both racing around to catch him during one of his impulse-driven adventures and trying to master a very new lens. As a result, his face is a little soft here, but I don’t know if that’s so bad, now that I view it with new eyes. The light in the room was itself pretty anemic, leaking through a window from a dim day, and running wide open on a 50mm f/1.8 lens at a slow 1/40 was the only way I was going to get anything without flash, so I risked misreading the shallow depth of field, which I kinda did. However, I’ll take this face over the other shots I took that day. Whatever I was lacking as a photographer, Henry more than compensated for as a subject.

Final box score: the boy in the ball cap hit it out of the park.

Thanks, Hank.

GIVE IT YOUR WORST SHOT

Are you going to say that Robert Capa’s picture of the D-day invasion would speak any more eloquently if it were razor-sharp? I didn’t think so.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE EARLY YEARNING OF PHOTOGRAPHERS TO MASTER OR EXCEED THE TECHNICAL LIMITS OF THEIR MEDIUM led, in the 1800’s, to a search for visual “perfection”. For rendering tones accurately. For capturing details faithfully. And, above all, for tight, sharp focus. This all made perfect sense in an era when films were so slow that people sitting for portraits had to have steel rods running up the backs of their necks to help them endure three-minute exposures. Now, mere mechanical perfection long since having become possible in photography, it’s time to think of what works in a picture first, and what grade we get on our technical “report card” second.

This means that we need no longer reject a shot on technical grounds alone, so long as it succeeds on some other platform, especially an emotional one. Further, we have to review and even re-review images, by ourselves as well as others, that we think “failed” in one way or another, and ask ourself for a new definition of what “failure” means. Did the less-than-tack-sharp focus interfere with the overall story? Did the underexposed sections of the frame detract from the messaging of what was more conventionally lit? Look to the left. at Robert Capa’s iconic image of the D-Day invasion at Normandy. He was just a little busy dodging German snipers to fuss with pinpoint focusing, but I believe that the world jury has pretty much ruled on the value of this “failed” photo. So look inward at the process you use to evaluate your own work. Give it your worst shot, if you will, and see what you think now, today.

The above image came from a largely frustrating day a few years back at a horse show in which I spent all my effort trying to freeze the action of the riders, assuming that doing so would deliver some kind of kinetic drama. I may have been right to think along these lines, but doing so made me automatically reject a few shots that, in retrospect, I no longer think of as total failures. The equestrienne in this frame looks as eager, even as exhausted as her mount, and the slight blur in both of them that I originally rejected now seems to work for me. There is a greater blur of the surrounding arena, which is fine, since it’s merely a contextual setting for the foreground figures, but I now have to wonder if I would like the picture better (given that it’s supposed to be suggestive of speed) if the foreground were completely sharp. I’m no longer so sure.

I think that all images have to stand or fall on what they accomplish, regardless of discipline or intention.We only kid ourselves into equating technical perfection with aesthetic success. Sometimes they walk into the room hand in hand. Other times they arrive in separate cars.

SETTING THE CAPTIVES FREE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’D LIKE TO ERADICATE THE WORD “CAPTURE” FROM MOST PHOTOGRAPHIC CONVERSATIONS. It suggests something stiff or inflexible to me, as if there is only one optimum way to apprehend a moment in an image. Especially in the case of portraits, I don’t think that there can be a single way to render a face, one perfect result that says everything about a person in a scant second of recording. If I didn’t capture something, does that mean my subject “got away” in some way, eluded me, remains hidden? Far from it. I can take thirty exposures of the same face and show you thirty different people. The word has become overused to the point of meaningless.

We are all conditioned to think along certain bias lines to consider a photograph well done or poorly done, and those lines are fairly narrow. We defer to sharpness over softness. We prefer brightly lit to mysteriously dark. We favor naturalistically colored and framed recordings of subjects to interpretations that keep color and composition “codes” fluid, or even reject them outright. It takes a lot of shooting to break out of these strictures, but we need to make this escape if we are to move toward anything approaching a style of our own.

I remember being startled in 1966 when I first saw Jerry Schatzberg’s photograph of Bob Dylan on the cover of the Blonde On Blonde album. How did the editor let this shot through? It’s blurred. It’s a mistake. It doesn’t…..wait, I can’t get that face out of my head. It’s Bob Dylan right now, so right now that he couldn’t be bothered to stand still long enough for a snap. The photo really does (last time I say this) capture something fleeting about the electrical, instantaneous flow of events that Dylan is swept up in. It moves. It breathes. And it’s more significant in view of the fact that there were plenty of pin-sharp frames to choose from in that very same shoot. That means Schatzberg and Dylan picked the softer one on purpose.

There are times when one 10th of a second too slow, one stop too small, is just right for making the magic happen. This is where I would usually mention breaking a few eggs to make an omelette, but for those of you on low-cholesterol diets, let’s just say that n0 rule works all the time, and that there’s more than one way to skin (or capture) a cat.

DESTROY IT TO SAVE IT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE TIMES WHEN THE RAW VISUAL FLOOD OF INTENSE COLOR IS THE MOST INTOXICATING DRUG ON THE PLANET, at least for photographers. Sometimes you are so overcome with what’s possible from a loud riot of hues that you just assume you are going to be able to extract a coherent image from it. It happens the most, I find, with large, sprawling events: festivals, open restaurants, street fairs, carnivals, anywhere your eyeballs just go into overload. Of course there must be a great picture in all this, you promise yourself.

And there may be. But some days you just can’t find it in the sheer “Where’s Waldo”-ness of the moment. Instead, you often wind up with a grand collection of clutter and no obvious clues as to where your viewer should direct his gaze. The technical term for this is “a mess”.

I stepped in a great one the other day. It’s a local college-crowd bar in Scottsdale, Arizona, where 99% of the customers sit outside on makeshift benches, shielded from the desert sun by garish Corona umbrellas, warmed by patio heaters, and flanked by loud pennants, strings of aerial lightbulbs and neon booze ads. The place radiates fun, and, even during the daylight hours before it opens, it just screams party. The pictures should take themselves, right?

Well, maybe it would have been better if they had. As in, “leave me out of it”. As in, “someone get me a machete so I can hack away half of this junk and maybe find an image.” Try as I might, I just could not frame a simple shot: there was just too much stuff to give me a clean win in any frame. In desperation, I shot through a window to make a large cooling fan a foreground feature against some bright pennants, and accidentally did what I should have done first. I set the shot so quickly that the autofocus locked on the fan, blurring everything else in the background into abstract color. It worked. The idea of a party place had survived, but in destroying my original plan as to how to shoot it, I had saved it, sorta.

I have since gone back to the conventional shots I was trying to make, and they are still a vibrant, colorful mess. There are big opportunities in big, colorful scenes where showing “everything in sight” actually works. When it doesn’t, you gotta be satisfied with the little stories. We’re supposed to be interpreters, so let’s interpret already.

THE RELENTLESS MELT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE PEOPLE YOU PHOTOGRAPH BECAUSE THEY ARE IMPORTANT. Others are chosen because they are elements in a composition. Or because they are interesting. Or horrific. Or dear in some way. Sometimes, however, you just have to photograph people because you like them, and what they represent about the human condition.

That was my simple, solid reaction upon seeing these two gentlemen engaged in conversation at a party. I like them. Their humanity reinforces and redeems mine.

This image is merely one of dozens I cranked out as I wandered through the guests at a recent reception for two of my very dearest friends. Given the distances many of us in the room traveled to be there, it’s unlikely I will ever see most of these people again, nor will I have the honor of knowing them in any other context except the convivial evening that herded us together for a time. Because I was largely eavesdropping on conversations between small groups of people who have known each other for a considerable time, I enjoyed the privilege often denied a photographer, the luxury of being invisible. No one was asked to pose or smile. No attempt was made to “mark the occasion” or make a record of any kind. And it proved to me, once more, that the best thing to relax a portrait subject is……another portrait subject.

I assume from the body language of these two men that they are friends, that is, that they weren’t just introduced on the spot by the hostess. There is history here. Shared somethings. I don’t need to know what specific links they have, or had. I just need to see the echoes of them on their faces. I had to frame and shoot them quickly, mostly to evade discovery, so in squeezing off several fast exposures I sacrificed a little softness, partly due to me, partly due to the animated nature of their conversation. It doesn’t bother me, nor does the little bit of noise suffered by shooting in a dim room at ISO 1000. I might have made a more technically perfect image if I’d had total control. Instead, I had a story in front of me and I wanted to possess it, so….

Susan Sontag, the social essayist whose final life partner was the photographer Annie Liebovitz, spoke wonderfully about the special theft, or what she called the “soft murder” of the photographic portrait when she noted that “to take a photograph is to participate in another person’s mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.”

Melt though it might, time also leaves a mark.

Caught in a box.

Treasured in the heart.

Related articles

- Susan Sontag Musings Where You Least Expect Them (hintmag.com)

FROM TOY TO TOOL

Selective focus can help direct your viewer’s eye. Taken with a Lensbaby Spark lens at 1/80 sec., f/5.6, ISO 320, 50mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A LONG STANDING BIT ON THE DAVID LETTERMAN SHOW, rather than claiming to be entertaining, actually poses the question of what entertainment actually is. Entitled “Is This Anything?”, the feature consists of about thirty seconds of acts or feats that might be amazing (like juggling), might be banal (like, um, juggling) or might qualify as merely strange. After the curtain is drawn, Dave and Paul briefly discuss the merits of what ever strangeness just transpired, and ask each other if “that was anything”. Sometimes there is no clear-cut decision. The show has disclaimed responsibility, and entertainment remains in the eye of the beholder.

That’s how you can feel the first time you use a Lensbaby.

Released several years ago to inventor Craig Strong’s great monetary benefit, the Lensbaby comes in a variety of

levels but is essentially an affordable tilt-shift attachment, a way to soften focus over selective areas of the frame while rotating the “sweet spot” of sharper focus wherever the shooter feels it should go. Now, essentially, selective focus is really part of every photo ever taken, since a choice of depth-of-field is made every time the shutter snaps. Lensbaby, however, offers the chance to pre-design the precise level of left-right, high-low focus, in the camera, and before the shot is taken. No post-processing is needed, and each use of the effect is completely under the shooter’s control, and at a fraction of what dedicated DSLR lenses cost.The Lensbaby effect is understandably an attractive gimcrack for the instinctive subculture of lo-fi photography, they of the hipster nonchalance and light-leaking, fixed-focus plastic cameras. Hey, it looks freaky, random, edgy. But, like everything else in your kit bag, it’s either toy or tool. The verdict as to which it is comes out one picture at a time.

So far I am whelmed….not overwhelmed, not underwhelmed. For one thing, Lensbabies are a lot of extra work. The entry-level model, the Spark, is actually a lens within a springy plastic bellows. You have to hold your camera body, delegate fingers from both hands to rotate the axis of the front of the lens, squeeze the bellows to bring part of the frame into focus (the Spark’s “sweet spot” is fixed at f/5.6), allocate another finger for the shutter, and click. At least you can’t carp about not having enough creative control. There’s more than enough of that, especially at first, to O.D. on. Your chosen area of focus can be held in place more easily with upgrade models (which also include additional optics and add-ons), but the Lensbaby is truly best for shoots where you have a lot of time to think, plan, and create….the very opposite of the “shoot from the hip” attitude embraced by the lomography crowd. You will take a lot of pictures that miss by inches, or fractions of inches.

What will move me from whelmed to overwhelmed will be finding those images where the Lensbaby effect actually aids my storytelling, yet does not define it, as in the lucky shot at the top of this post. The camera gadgets I eventually consign to the “toy” pile go there because they call too much attention to what they can do, not to what I can do using them. The”tools” pile contains the gear that is essential to my saying something in a distinctly different voice. Finally, the two piles are divvied up only after taking lots of pictures and asking a ton of questions (a few gimmicks, like fisheye, have spent time in both piles; hey, I’m not above just playing around).

I sympathize with Letterman’s dilemma when he ironically asks, “Is this anything?” Selective focus is a way to install big neon pointers into your pictures, a more emphatic command to look over here. It’s also a way to amplify the drama of certain data or simplify cluttered compositions. I get it.

But it needs to be about much more than that. Or, more correctly, I have to help it.

Related articles

- My Lensbaby SCOUT, baby! (greyiscolour.wordpress.com)