ACCIDENTALLY ON PURPOSE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE IMAGE SHARING GROUP UTATA, which operates within Flickr, has been, for this boy snapper, a daily touch of Christmas. It expands upon the rather pointless online quest for mere “likes” and is, instead, a genuine dialogue with other like-minded strange-o’s who want to push the boundaries of at least their own eyes and commiserate with others who long to do the same. The administrators keep Utatans united with periodic, deadline-based homework assignments organized along a a variety of seriously unconventional themes. Some require serious thought. Some can be created almost completely on impulse. And many more fall somewhere in between.

One of the nice bits of insta-fame conferred upon Utatans is having their work occasionally plugged onto the utata.org welcome page. Even better, head honcho Greg Fallis and his fellow guardians of the Utata universe will often provide new captions, poems, or essays of their own for the images, as if to tangibly demonstrate that, just as there is more than one way to see, there are a million ways to be seen. Upon recently conferring home-page status on a rather hurried celphone image I’d posted, Greg also managed to perfectly crystallize thoughts I’ve mulled over recent years:

See, here’s the thing about shooting photographs with your cell phone: it’s not a serious camera. That means you can relax. Try stuff. Shoot something different. Shoot something familiar in a different way. Shoot something different in a familiar way. It’s liberating because it’s “just” your cell phone.

In fact, the image was made in a very short space of time, shorter by far than if I’d made it with my “real” cameras. The original phone selfie was fed through an app designed to mimic both the strengths and weaknesses of antique portrait lenses, and, since I liked the ethereal quality it delivered, I decided to stop. Just stop. Stop fooling, fretting and fixing. Stop, and publish.

So, have I gotten to the point, at least some of the time, when I’m really living that old saw that “the best camera is the one you have with you?” Am I more spontaneous, more open to experiment, higher up the “wot the hell” scale when armed with a cel? Dunno. Really. Not being coy. I definitely still feel that umbilical-cord connection to my trad gear. But I dig immediate gratification as well, at least the gratification of shortening the gap between “wonder what would happen” and “hmm, that kind of worked.”

Is my conventional gear more “real”than my iPhone? Well, how do you define real? Obviously, there is an almost infinite number of post-processing tools available to compensate for whatever shortcomings the cameras themselves might possess. So, if I do advance prep in a DSLR before the shutter snap to ensure a good picture, does it disqualify an image if I snap it first and then enhance it afterwards in a cel? What is a darkroom? What is a workflow?

Big questions. And I don’t always get the same answers when I ask them.

GET YOUR MIND RITE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“REALITY”, THOUGHT TO BE the normal end product of the process of pointing a camera at something, is actually rather limiting. Sure, our little boxes were originally created as an accurate, even scientific means for recording our world.. a method more reliable, somehow, than the imprecision of the painter. Soon afterward, however, the camera longed for a soul of its own, or at least the painter’s freedom to make a subjective choice as to what “real” should look like.

Bottom line: for photographers, mere reality turned out to be, well, kind of a yawner.

To go even further, it seems to me that certain subjects actually call for a kind of unworldly, almost hallucinatory quality, an attempt to make things look not like what they are but how they feel. Of course, we can’t actually show emotions or states of mind, but various photographic techniques can, and should suggest them.

In visualizing ritual, ceremony, sacrament, or tradition, for example, you’re not merely chronicling activity. You’re also photographing mystery, or an extra dimension of consciousness. The above image, in terms of mere reality, is of a class for museum visitors curious to learn bout the Brazilian ritual of capoeira, a traditional fake-fighting martial arts performance that is performed during carnival and other national festivals. Now, you can shoot such a subject “realistically” (evenly lit, uniform focus, sharp detail), or aesthetically (dark, selectively blurred, even a little confusing), depending on what kind of feel you’re going for. This goes to the heart of interpretation. You’re not merely presenting reality: you are representing it.

Photographs originate in the mind, not in the camera, and so it must follow that there are as many “realities” as there are photographers.

RE-ASSIGNING VALUE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY DEMONSTRATED, EARLY IN ITS HISTORY, that, despite the assumption that it was merely a recording device, it regarded “reality” as….overrated. Since those dawning daguerreotype days, it has made every attempt possible to distort, lie about, or improve upon the actual world. There is no “real” in a photograph, only an arrangement between shooter and viewer, who, together, decide what the truth is.

So-called street photography is rife with what I call “reassigned value” when it comes to the depiction of people. Obviously, the heart of “street” is the raw observation of human stories as the photographer sees them, tight little tales of endeavor, adventure…even tragedy. However, the nature of the artist is not to merely document but also to interpret: he may use the camera to freeze the basic facts of a scene, but he will inevitably re-assign values to every part of it, from the players to the props. He becomes, in effect, a stage manager in the production of a small play.

In the above image you can see an example of this process. The man sitting at his assigned post at a museum gallery began as a simple visual record, but I obviously didn’t let the matter end there. Everything from the selective desaturation of color to the partial softening of focus is used to suggest more than what would be given in just a literal snap.

So what is the true nature of the man at the podium? Is he wistfully gazing out the distant window, or merely daydreaming? Is he regretful, or does he just suffer from sore feet? Is he chronically bored, or has his head in fact turned just because a patron asked him the direction of the restroom? And, most importantly, how can you creatively alter the perception of this (or any) scene merely by dealing the cards of technique in a slightly different shuffle?

Photographers traffic in the technical measure of the real, certainly. But they’re not chained to it. The bonds are only as steadfast as the limit of our imagination, or the terms of the dialogue we want with the world at large.

FIVE MINUTES OF FANCY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PUTTERING SUFFERS A BAD REPUTATION, coming somewhere on the disreputability scale between “screwing around” and “just passing the time”, poking an insolent finger in the eye of the Puritan work ethic. The headmaster’s voice echoes from the land of Hard-Won Wisdom: Time is money. Make something of yourself. Whattaya gonna do, waste the entire day?

Yeah, replies the photographer within you. Thought I might….

Making a picture isn’t the same process as building a bridge. You don’t always end the project with the same aims as you began with. Like any other artistic enterprise, the answer might come in the journey, rather than the destination. And a photographer, caught in mid-creation and asked, “what you doing?” should be quite comfortable answering, “you know, I’m not really sure yet…”

The above image is a total exercise in “let’s see what happens if I do this“, and at no time in the making of it did I have a set plan or firm objective: I just did know when to stop, but everything else was negotiable in the moment. I wasn’t wasting time: I was investing it.

At first, I was trying to take a picture of my back yard, which over my shoulder, as it was reflected in the glass cabinet door in front of me. I was about to kill the power on the amplifier on a shelf behind the door when a test shot revealed something unusual. At my chosen aperture, the amp’s two red LEDs weren’t reading as sharp points of light, but as diffuse outer circles surrounding soft inner circles, almost like a pair of feral eyes. And at that point, the garden scene slowly started to take a back seat.

Shooting the glass door at a slight angle made my body register as a reflection, while shooting straight on turned me into a silhouette, which would become handy. Now that I was just a shape, I could be anything, so I positioned myself to where the dots indeed appeared to glowing, spooky eyes. Shooting with my right hand, my body details now masked by shadow, I crossed my left hand over beyond the right edge of my body, posing it to look as if I were stealing something, or perhaps twisting the dial on a combination safe. Having thus established the behavior for the character I was now creating, I grabbed my wife’s garden hat and threw a bed blanket around my shoulders for some sinister atmosphere. Click and done, with my newly imagined Phantom Blot plotting his way into the house. I didn’t know the whole story, but I knew when to stop playing. Total time investment: five big minutes.

You won’t always have an organized blueprint for a picture when you set about making one. Besides, if you confine yourself solely to the familiar when shooting, eventually all of your photos will start to resemble each other, and not in a good, “cohesive body of work” way.

Screw with the formula. Embrace the uncertain.

WHAT DREAMS MAY COME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MEMORY ISN’T SHARPLY DEFINED OR TIDY, and so the act of conjuring remembrance in art is never as forensically factual as sliding open an autopsy drawer. The yester-thing that we treasure most dearly are the true opposite of clinical artifacts: they are, instead, bleary, distorted, indistinct, and mysterious. Small wonder that trying to fix memory on a camera sensor is like trying to pitchfork smoke.

Creating images in an attempt to capture the past is a huge part of photography, but it’s a no-man’s land without clear markings or signs. We begin our visual argument by asserting that our version of a memory is the official one… but official according to whom? Even people who have shared a specific event will offer different testimony of what it “really” was. And that very subjective uncertainty becomes one of photography’s greatest charms.

It only took a few years for early shooters to conclude that photographs need not be confined to merely measuring or documenting the world. Early on, they enlisted fancy and whimsy to the cause of depicting memory, just as painters did. And conversely, once there was a machine like the camera to perform the task of faithfully recording “reality”, painters began to abandon it for Impressionism and everything that followed after. Both arts began, like Alice, to regularly venture out on both sides of the looking glass.

A great part of photography’s allure is in discovering how little objective reality has to be in image involving memory, and what an adventure it is to escape the actual in the pursuit of the potential. The camera lets us tell lovely lies in pursuit of the truth.

YOU AND YOUR BRIGHT IDEAS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE SELF–EDUCATION PROCESS INHERENT in photography is perpetual: that is, the lesson-learning doesn’t “clock out” merely because a given task is completed, but flows equally during the in-between moments, the spaces outside of,or adjacent to, the big ideas and big projects. Down time need not be wasted time.

Often it’s because the pressure of delivering on a deadline is absent that we relax into a more open frame of mind as regards experimentation. You find something because you’re not looking for it.

One such area for me is lighting. I seldom use flash or formal studio lights, so I obsess over cheap, mobile, and flexible means of either maximizing natural light or adding artificial illumination in some simple fashion. This isn’t just about making an object seem plausibly lit, or, if you like, “real: it’s also about choosing or sculpting lighting schemes, making something look like I want it to.

Small, powerful LEDs have really given me the chance to fill spare moments cranking out a wide array of experimental shots in a limited space with little or no prep, producing shaping light from every conceivable angle. I just lock the camera down on a tripod, make some simple arrangement on a table top, and shoot dozens of frames with different directional sweeps of the light, usually over the space of a time exposure of around a half a minute. I can move the light in any pattern, either by holding it static or tracking high/low, left/right, etc.

Frequently this activity does not result in a so-called “keeper” image. Such spare-time experiments are about process, not product. The real pay-off comes somewhere further down the road, when you have need of a skill that you developed over several days when you had.. nothing to do.

THE OTHER SIDE OF SOFT

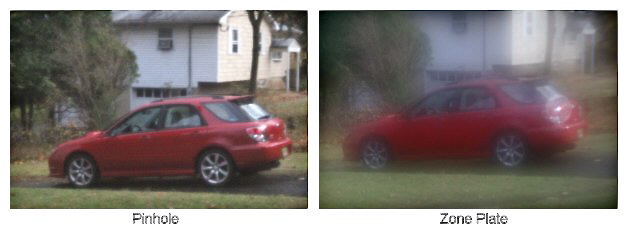

A side-by-side comparison of the two main systems of “lensless” photography, the pinhole and the zoneplate.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS (AND HUMANS IN GENERAL) ARE CONTRARY. Tell them they’re forever stuck with a bones-basic camera and they’ll spend every night and weekend either trying to devise a more sophisticated device or work three jobs so they can buy one. And the obverse is also true: present shooters with an infinite number of hi-tech choices designed to deliver unprecedented precision, and they’ll perversely start to pine for the “lost innocence” or “authenticity of the bare-bones rig.

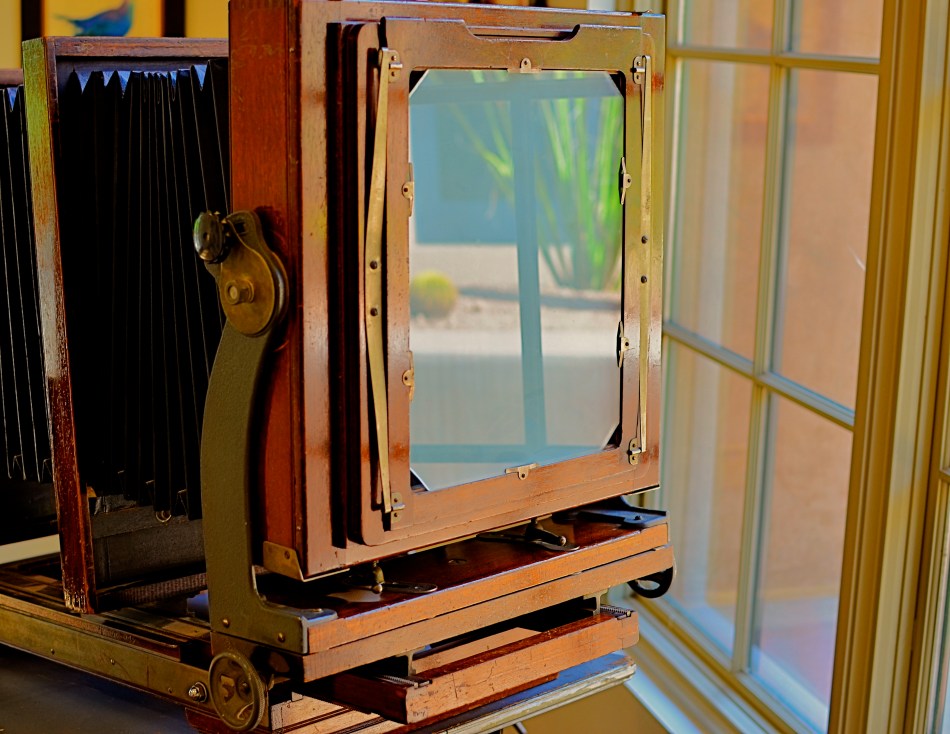

What else can account for the recent surge in lensless photography, and the creation of images with cameras that are more technically handicapped than even one’s first point-and-shoot? Of course, the very first image capturing was done without a lens, with the ancient Greeks creating pictures on the inside back panel of a camera obscura box, using nothing but a small pinhole to generate a dim, soft-focused image of the chosen subject. The early nineteenth century replaced the hole with custom-designed glass optics, and photography moved quickly from a scientific experiment to a global rage.

But, of course, for photographers, no part of their art’s history is really “past”, and so we now see a small explosion of new pinhole devices for both film-based and digital cameras, from specially manufactured pinhole body caps (used in place of a lens) to cardboard kits available as DIY projects to recently dedicated pinhole plug-in optics for the Lensbaby series of lenses. The idea remains the same: small apertures, virtually infinite depth of field, soft focus, and looong exposures.

The other variable in this craze is the popularity of zoneplates, which, unlike the refracted light in a pinhole, works with more scattered diffracted light, creating a halo glow in the high contrast areas of subjects, as if the soft-focus is also being viewed through a gauzy haze. A zoneplate is really like a bulls-eye target, a plate where both opaque and transparent “rings” combine to disperse light widely, delivering a dreamier look than that seen in a pinhole image. The other big difference is that a zoneplate has a much larger light gathering area and a wider aperture, so while a pinhole opening might equate to a stop as small as f/177, the zoneplate could be as wide as, say, f/19, making handheld exposures (and visualizing through a viewfinder) at least feasible, if tricky.

Of course, both kinds of lensless imaging are extremely soft, rendering a precise depiction of your subjects impossible. However, if light patterns, shapes, and mood outweigh the importance of sharpness for a certain kind of picture, then pinholes and zoneplates are cheap, fairly easy to master (you don’t have much control, anyway), and a little bit like stepping back in time.

It’s contrary….but ain’t we all.

HOLDING HANDS IN THE DARK

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE THING OF WHICH THE PHOTOGRAPHIC COSMOS IS NOT IN SHORT SUPPLY IS THE SELF-PORTRAIT. What might have been a specialized kind of image-making just a few scant years ago is now, in the mobile era, a flat-out obsession. We snap ourselves being happy, being moody, eating a cheeseburger, or giving that cheeseburger a thumbs up with friends, etc, etc. We make more photographs than ever of our faces, and, it could be argued, say less and less in the process.

I think that a good self-portrait, if it is to say or imply anything true about the life behind the face, requires a little prep time, or at least a pre-conceived notion of what one is trying to reveal about that person. That said, I think our concept of a selfie is, at the very same time that it’s overdone, is also far too narrow. Simply speaking, there are other parts of our physical envelope that convey information about who we are and what we’ve been in the world. The hands, for example.

Pax Humana (2017). Hand-held LEDs used to “light-paint” in the dark can create interesting textures in human skin. 18 sec., f/16, ISO 100, 35mm.

If the eyes are the window to the soul, the fingers are the foot-soldiers who carry out the orders that the soul dreams up. The mind behind the face can certainly shine through a good facial portrait, but consider that the hands are the real agents of change in a person’s life. They lift: they move: they put plans into action. Moreover, hands bear the traceable time-stamps of all that agency. Each wrinkle and scar is a document of both deliberate action and unforeseen consequence. Hands belong in any serious study of a person’s life, no less than the face. The trick, as with photographing every other subject, is in getting the image you want.

I find, for example, that normal room light keeps a lot of fine detail from registering in an image, since human skin is highly reflective, causing the grain of the skin to wash out. One way to get around that is to use light painting, a technique we’ve discussed here before. Set up your composition and focus with the camera on a tripod in normal light, then leave everything in place until nightfall and make the image in a completely darkened room while experimenting with a range of exposure times. Your only illumination will be a small hand-held LED, such as a miniature key chain flashlight….nothing wide-beam or super-powered. Use a wireless remote to trigger your shutter, then “write” light paths over the hand, slowly tracking the LED over small areas until all have been “hit” before the trigger snaps back shut.

In the above example, I wanted greater contrast between the hills and valleys of my knuckles, veins, etc., and I wanted to minimize the shine-making effect of the light, so I lit from an angle, sideways from the tips of the fingers. That bumped up the pores and hairs into starker relief as well. Two things to remember: using short stabs of light, that is, turning the LED rapidly on and off, is better than a continuous beam, since you can pinpoint the effect more precisely. Also, using a very small aperture (f/16 here) provides maximum depth of field and enhanced detail. Other than that, it’s truly trial-and-error. This frame, as an example, is one of forty attempts, so it’s not a project you do on the fly. But this, I feel, is my hand, my real hand, its labors and history in full view. And it’s as much a portrait as any face can ever provide.

VISUAL SHORTHAND

On The Barrelhead (2017). Given your mind’s files on what, visually, a “dollar” is, not much literal detail is needed to convey said object in a photo.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONLY A SMALL PERCENTAGE OF OUR MIND’S INNER LIBRARY OF ACCUMULATED DATA is at the top of our consciousness. Staying aware of everything we’ve learned in our lives, every minute of the day, would obviously lead to a mental train wreck, as the vital and the trivial created an endless series of collisions between what we need to know and what we need to know right now. The brain, acting as a wonderful prioritizing network, moves information to the foreground or tucks it toward the back, as needed.

The visual patterns we’ve developed over a lifetime are also at work in how we create and interpret photographs. We know in an instant when we’ve seen something before, and so we process known objects in a kind of short-hand rather than as something we’re viewing for the first time. This allows us to make camera images that are abbreviated versions of things we first encountered long ago, images that merely suggest things, rather than delineate them in full detail. Call it abstraction, call it minimalism, heck, call it a ham sandwich if that helps. It merely means that we can use our brain vaults to show parts of things, and count on our memories to recognize those things solely from the parts.

Focus is but one such way of supplying visual information to the brain, and its selective use allows the photographer to convey the idea of an object without “spelling it out”, or showing it in absolutely documentarian terms. In the image above, our collective memory of the contours and details of a dollar bill are so deeply ingrained that we don’t actually need to see all of its numbers, letters, and images in full definition. Focus thus becomes an accent, a way of highlighting some features of a subject while downplaying others.

It may be that, in photographing selective aspects of objects rather than showing their every detail, we are teaching the camera to act like the flashing fragments of memory that our mind uses to transmit information….that is, teaching a machine to see in the code that we instinctively recognize. Is all interpretation just an attempt to ape the brain’s native visual language? Who knows? All that we really have to judge an image by is the final result, and its impact upon other viewers like ourselves.

COUNTRY MOUSE, CITY MOUSE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY ARTIST MUST KNOW WHICH CANVAS (or platform) is best for his particular work. And while photography is so rangy and wide, trying to find an area of speciality is no great challenge, so long as you are honest with yourself as to what your eye can effectively deliver. Do portraits alone help your vision pour forth? Then move in that direction, certainly. Drawn to minimalism as a way of expression? Then simplify, my son, simplify, and go in peace.

In fact, my own visual bias, if that’s the word, runs counter to my earliest influences. The first photographs that made me gasp in awe were, in fact, landscapes, since, as a boy, I collected many travel slides and magazines which emphasized life in the natural world. However, my second great influence was that of the great urban photographers, both journalists and poets, whose medium was the man-made, and not the organic, type of mountain. And even though I continued to marvel at the stunning statements made by naturalist shooters, I came to know that I did not have anything particularly wise or wonderful to contribute in that area.

I love nature. It is restorative, contemplative, and any other “ive” you choose. However, I cannot, personally, produce anything poetic or glorious in depicting it. I envy ecumenical writers like Walt Whitman, who reveled in both mountain and city street alike, describing both with incredible passion and power. As a photographer, however, I decided long ago to shoot where my eye is most organically excited…and that’s the city. I can never completely abandon scenic subjects, since I continue to hold out hope that one or another of them will make my heart leap to my throat, and, in turn, make a great vision leap into my camera.

Of course, the longer you make photographs, the more universal your purely technical competence becomes, in that you can deliver a serviceable picture regardless of the assignment. But a photograph is never merely a recording, and simply making an adequately composed, reasonably exposed frame is no greater an achievement than waiting the requisite number of minutes to soak a tea bag. It’s not so much knowing how to make the picture as wanting to, since that desire is the principal difference between acceptable and exceptional. Of course, passion is also not enough, any more than technical acumen is. But when the two meet, they will produce your best work.

As in the author’s mantra “write what you know about”, “shoot what you feel” must surely be a kind of aspirational prayer for better pictures. Can anyone say if a tree is less beautiful than a skyscraper? Not with any true authority. Point that camera where your heart points, and it’s hard to go far wrong.

THE LOVE OBJECT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN EARLIER OUTINGS, WE HAVE DISCUSSED THE VALUE of knowing how sunlight enters your house at all times of the day. Knowing where bright spots and slatted beams hit the interior of your home in different hours gives you a complete map of “sweet spots” where natural light will temporarily isolate and flatter certain objects, giving you at least several optimized minutes for prime shooting each day.

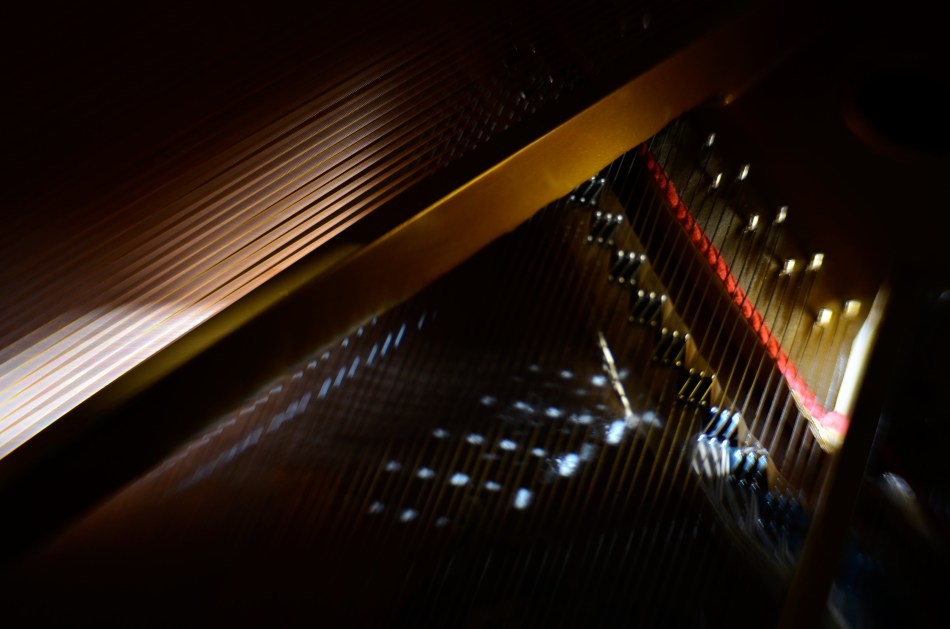

Keeping this little time-table in your head allows you to move your subjects to those places in the house where, say, the daily 10 a.m. sun shaft through the family room window will give you a predictably golden glow. For me, that location is my living room window, across which the southwestern sun tracks east/west, and the object is my white baby grand piano.

Pianos, to me, are divinely complex gadgets, creations of the first great industrial age, their impossibly intricate mechanics offering thousands of possibilities for macro shots, fisheye explosions, abstract compositions, shadow studies, and delicate ballets of reflections as the morning sun dances across harp, strings, and hammers in an endless kaleidoscope of radiance. I have long since tracked how the sun showcases different parts of the piano as the day progresses, and how that corresponds to the instrument’s various sections and subsections.

Hard-wiring that schedule into my skull over the years means I know when a shot will work and when it won’t, making the object more than just something to shoot. It becomes, in effect, an active kind of photo laboratory, a way of teaching and re-teaching myself about the limits of both light and my own abilities. Better still, the innate intricacy of the piano as an object guarantees that I can never really get “done” with the project, or that something that was a mystery in January will become a revelation by June.

What gives this process a special lure to me is my endless effort to exploit natural light to the full, believing, as I do, that nearly every other less organic form of illumination is measurably poorer and less satisfactory than that which comes plentifully, and for free. The house I live in has thus become, over the years, a kind of greenhouse for the management of light, an active farm for harvesting the sun.

APPEARS TO BE…..

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I RECALL, MANY YEARS AGO, WHEN THE JUICIEST COMPLIMENT I COULD IMAGINE SNAGGING for a photograph was that “it looks just like a postcard”. That is to say, “the picture you’ve made looks like another picture someone else made while trying to make something look like…. a picture”.

Or something like that.

Seems that an incredible amount of photography’s time on earth has been spent trying to make images not so much be something as to be like something else. The number of effects we go for when making an image, in the twenty-first century, is a list of the inherited techniques and processes that have waxed and waned, and waxed again, over the entire timeline of the art’s history. We are now so marinated in all the things that photographs have been that we find ourselves folding the old tricks into new pictures, without self-consciousness or irony. Consider this partial roster of the things we have tried, over time, to make images look like:

Paintings Etchings Drawings Daguerreotypes Tintypes Cyanotypes Expired film Cross-Processed Film Kodachrome Sepiatone Toy Cameras Macro Lenses Badly-focused, Damaged and Flawed Lenses Obsolete Film Stock Daytime Night-Time Negatives Postcards Antique Printing Processes Dreams, Hallucinations, and Fantasies “Reality”

We not only manipulate photographs to make them more reflective of reality but to mock or distort it as well. We make pictures that pretend that we still have primitive equipment, or that we have much better equipment than we can afford. We utilize tools that make pictures look tampered with, that accentuate how much they’ve been tweaked. We make good pictures look bad and bad pictures look passable.

This post is turning out to be the evil twin of a recent article in which I emphasized how little we know about making “realistic” images. The more I turn it over in my mind, however, the more I realize that, in many cases, we are trying to make new photographs look like photographs that someone else took, in a different time, with different limits, with different motives. We steal not only from others but also from what they themselves were stealing.

All of a sudden my head hurts.

INCONVENIENT CONVENIENCE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE LONG SINCE ABANDONED THE TASK OF CALCULATING HOW MANY DIGITAL IMAGES ARE CREATED every second of every day. The numbers are so huge as to be meaningless by this time, as the post-film revolution has removed most of the barriers that once kept people from (a) taking acceptable images or (b) doing so quickly. The global glut of photographs can never again be held in check by the higher failure rate, longer turnaround time, or technical intimidation of film.

Now we have to figure out if that’s always a good thing.

Back in the 1800’s. Photography was 95% technical sweat and 5% artistry. Two-minute exposures, primitive lenses and chancey processing techniques made image-making a chore, a task only suited to the dedicated tinkerer. The creation of cheap, reliable cameras around the turn of the 20th century tilted the sweat/artistry ratio a lot closer to, say, 60/40, amping up the number of users by millions, but still making it pretty easy to muck up a shot and rack up a ton of cost.

You know the rest. Making basic photographs is now basically instantaneous, making for shorter and shorter prep times before clicking the shutter. After all, the camera is good enough to compensate for most of our errors, and, more importantly, able to replicate professional results for people who are not professionals in any sense of the word. That translates to billions of pictures taken very, very quickly, with none of the stop-and-think deliberation that was baked into the film era.

We took longer to make a picture back in the day because we were hemmed in by the mechanics of the process. But, in that forced slowing, we automatically paid more active attention to the planning of a greater proportion of our shots. Of course, even in the old days, we cranked out millions of lousy pictures, but, if we were intent on making great ones, the process required us to slow down and think. We didn’t take 300 pictures over a weekend, 150 of them completely dispensable, nor did we record thirty “takes” of Junior blowing out his birthday candles. Worse, the age’s compulsive urge to share, rather than to edit, has also contributed to the flood tide of photo-litter that is our present reality.

If we are to regard photography as an art, then we have to judge it by more than just its convenience or speed. Both are great perks but both can actually erode the deliberation process needed to make something great. There are no short cuts to elegance or eloquence. Slow yourself up. Reject some ideas, and keep others to execute and refine. Learn to tell yourself “no”.

There is an old joke about an airpline pilot getting on the intercom and telling the passengers that he’s “hopelessly lost, but making great time”. Let’s not make pictures like that.

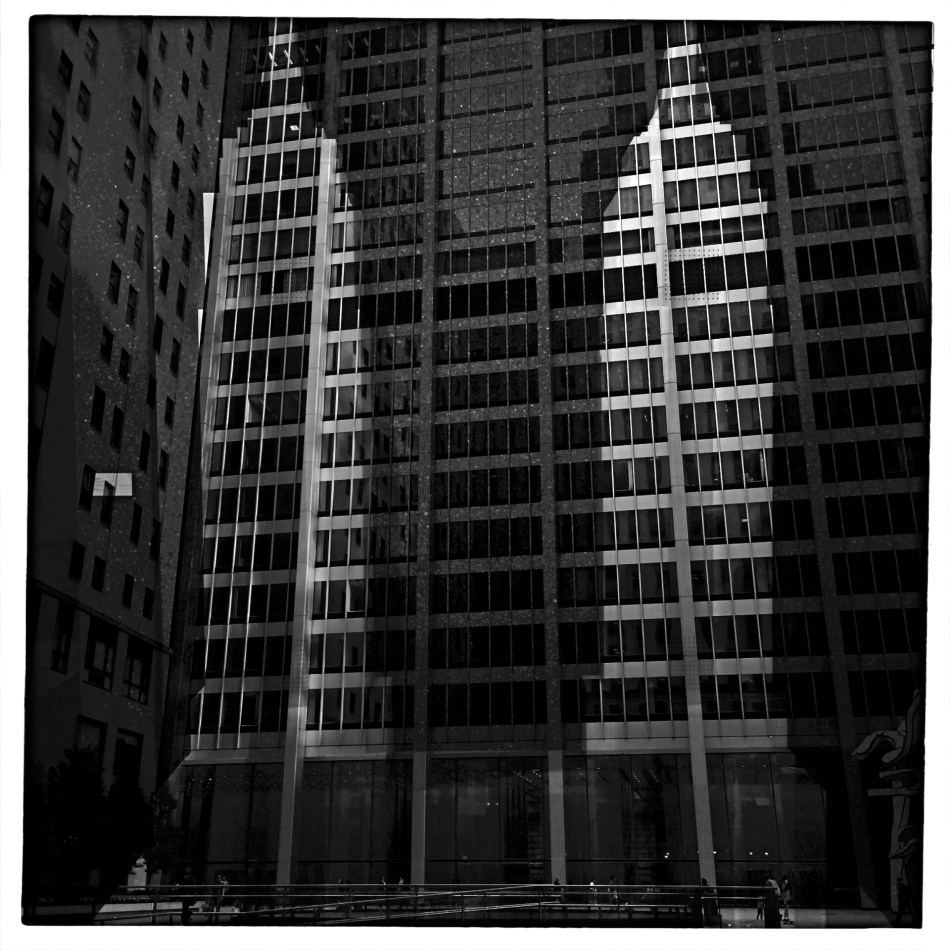

BURDEN OF PROOF

Reverse Shadows (2015) Originally conceived in color, later converted to black and white. Luckily, it worked out, but, shooting this image anew, I would execute it in monochrome from start to finish. Every story has its own tonal rules.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE WORLD OF PHOTOGRAPHY’S EMBRACE OF COLOR, which now seems instinctual and absolute, is actually a very recent thing. The arrival of color film stock targeted to the amateur market barely reaches back to the 1920’s, and its use in periodicals and advertising didn’t truly begin to outdistance color illustration until well after World War II. Color in so-called “serious” or “art” photography existed on the margins until half-way through the 1960’s, when hues, like every other element of the contemporary scene, gloriously exploded, creating a demand for color from everyone, amateur to pro. The ’60’s was also the first decade in which color film sales among snapshooters surpassed those of black and white.

Today, color indeed seems the default choice for the vast majority of shooters, with the “re-emergence” or “comeback” of black and white listed among each year’s top photo trend predictions. The ability to instantly retro-fit color images as monochrome (either in-camera or in-computer), has allowed nearly anyone to at least dabble in black & white, and the tidal wave of phone apps has made converting a picture to b&w an easy impulse to indulge.

And yet we seem to be constantly surprised that black & white has a purpose beyond momentary nostalgia or a “classic look”. We act as if monochrome is simply the absence of color, even though we see evidence every day that b/w has its own visual vocabulary, its own unique way of helping us convey or dramatize information. Long gone are the days when photographers regarded mono as authentic and color as a garish or vulgar over-statement. And maybe that means that we have to re-acquaint ourselves with b&w as a deliberate choice.

Certainly there has been amazing work created when a color shot was successfully edited as a mono shot, but I think it’s worth teaching one’s self to conceptualize b&w shots from the shot, intentionally as black and white, learning about its tonal relationships and how they add dimension or impact in a way separate from, but not better than, color. Rather than consistently shooting a master in color and then, later, making a mono copy, I think we need to evaluate, and plan, every shot based on what that shot needs.

Sometimes that will mean shooting black and white, period, with no color equivalent. Every photograph carries its own burden of proof. Only by choosing all the elements a picture requires, from color scheme to exposure basics, can we say we are intentionally making our images.

BITE-SIZE BEAUTY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN PHOTOGRAPHY, WE OFTEN HAVE THE OPPORTUNITY TO ADMIRE THINGS THAT ARE, STRICTLY SPEAKING, beyond our capabilities. The world is rife with people who master exposure, composition, editing and conceptualization in ways which make us gasp in a mixture of awe and envy. Sometimes, we are so amazed by artists outside our own area of expertise that we emulate their passion and, in doing so, completely remake our own art. Other times, we just glimpse their greatness like a kid peeking inside the tent flap at the circus. We know that something marvelous is going on in there. We also sense that we are not a part of it.

That’s pretty much been my attitude toward landscape work.

Much of it leaves me impressed. Some of it leaves me breathless. All of it leaves me puzzled, since I know that I am missing a part of whatever mystical “something” it is that allows others to capture majesty and wonder in the natural world, their images looking “created” my own looking merely “snapped”.

Sometimes the sheer size of nature’s canvas panics my little puppy brain, and I retire to smaller stories.

It’s not the same with urban settings, or with anything that bears the mark of human creativity. I can instinctually find a story or a sweet point of focus in a building, a public square, a cathedral. I can sense the throb of humanity in these places and I can suggest it in pictures. But put me in front of a broad canvas of scenery and I struggle to carve out a coherent composition. What to include? What to cut? What light is best? And what makes this tree more pictorially essential than the other 3,000 I will encounter today?

The masters of the landscape world are magicians to me, crafty wizards who can charm the dense forest into some evocative choreography, summoning shadows and light into delicate interplay in a way that is direct, dramatic. I occasionally score out in the woods, but my failure rate is much higher, and the distance between what I see and what I can deliver much greater. Oddly, it was the work of scenic photographers, not street shooters or journalists, that originally conveyed the excitement of being a photographer to me, although I quickly devolved to portraits, abstractions, 3D, hell, anything to get me back to town, away from all that scary flora and fauna.

Medium or bite-sized natural subjects do better for me than vast vistas, and macro work, with its study of the very structures and patterns of organic things works even better. But I forever harbor a dream of freezing a forest in time in a way that stuns with its serene stillness and simple dignity. I have to keep putting myself out there, hoping that I can bridge the gap between envy and awareness.

Maybe I’ll start at the city park. I hear they have trees there….

ROOM WITH A VIEW

This 1820’s view from the upper floor of Nicéphore Niépce’s house is generally acknowledged as the first true photograph, revealing rough details of a distant pear tree, a slanted barn roof, and the secondary wing of the estate (at right).

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MANY OF THE MOST IMPORTANT SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERIES ARE ACTUALLY DETOURS, things unearthed by accident in search of something completely different. Marconi was not looking to create the entertainment medium known as radio, but merely a wireless way to send telegraphs. The tough resin known as Bakelite was originally supposed to be a substitute for shellac, since getting the real thing from insects was slow and pricey. Instead, it became the first superstar of the plastics era, used to making everything from light plugs to toy View-Masters.

And the man who, for all practical purposes, invented photography was merely seeking a shortcut for the tracing of drawings.

Nicéphore Niépce, born in France in 1765, plied his trade in the new techniques of lithography, but fell short in his basic abilities as an artist, and searched for a way to get around that shortcoming by technical means. He became proficient in the creation of images with a camera obscura, a light-tight box with a pinhole on one side which projected an inverted picture of whatever it was pointed at on the opposite inside wall of the container, the pinhole acting as a glassless, small-aperture lens. Larger versions of the gadget were used by artists to project a subject onto an area from which tracings of the image could be done, then finished into drawings. Niépce grew impatient with the long lag time involved in the tracing work and began to experiment with various compounds that might chemically react to light, causing the camera’s image to be permanently etched onto a surface, making for a quicker and more accurate reference study.

Niépce tried a combination of fixing chemicals like silver chloride and asphalt, burning faint images onto surfaces ranging from glass to paper to lithographic stone. Some of his earliest attempts registered as negatives, which faded to complete black when observed in sunlight. Others resulted in images which could be used as a master from which to print other images, effectively a primitive kind of photocopy. Finally, having upgraded the quality of his camera obscura and coating a slab of pewter with bitumin, Niépce, around 1827 successfully exposed a permanent, if cloudy image from the window of his country house in La Gras. His account recalled that the exposure took eight hours, but later scientific recreations of the experiment believe it could actually have taken several days. Even at that, Niépce might have recorded a good deal more detail in the image had he waited even longer. In an ironic lesson to all impatient future shooters, the world’s first photograph had, in fact, been under-exposed.

Rather than merely create a short-cut for sketch artists, Nicéphore Niépce’s discovery, which he called heliography (“sun writing”), resulted in a new, distinctly different art that would compete with traditional graphics, forever changing the way painters and non-painters viewed the world. Centuries later, harnessing light in a box is still the task at hand, and the eternally novel miracle of photography.

SEPARATE WORLDS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MAYBE IT’S THE TERM ITSELF. MAYBE IT’S HOW WE DEFINE IT. Either way, for photographers, concept of the “still life” is, let’s just say, fluid.

I believe that these static compositions were originally popular for shooters for the same reason that they were preferred by painters. That is, they stayed in one place long enough for both processes to take place. Making photographs was never as time-consuming as picking up a brush, but in the age of the daguerreotype the practice was anything but instantaneous, with low-efficiency media and optical limitations combining to make for looooong exposure times. Thus, the trusty fruit-bowl-and-water-jug arrangement was pretty serviceable. It didn’t get tired or require a bathroom break.

But what, now, is a “still life”? Just a random arrangement of objects slung together to see how light and texture plays off their surfaces? More importantly, what is fair game for a still life beyond the bowl and jug? I tend to think of arrangements of objects as a process that takes place anywhere, with any collection of things, but I personally seek to use them to tell a story of people, albeit without the people present. If you think about museum collections that re-create the world of Lincoln or Roosevelt, for example, the “main subject” is obviously not present. However, the correct juxtaposition of eyeglasses, personal papers, clothing, etc. can begin to conjure them in a subtle way. And that conjuring, to me, is the only appeal of a still life.

I like to find a natural grouping of things that, without my manipulation or collection, suggest separate worlds, completely contained universes that have their own tools, toys, architecture, and visual vocabulary. In the above montage of angles and things found at a beach resort, I had fun trying to find a way to frame the “experience” of the place, in abstract, showing all its elements without showing actual activities or people (beyond the sunbather at right). The real challenge, for me, is to create associations in the mind of the viewer that supply all the missing detail beyond the surfboards, showers, and sundecks. That, to me, is the real attraction of a still life….or, more accurately, taking a life and rendering it, fairly intact, in a still image.

Hey, it’s not that I don’t like a good bowl of fruit now and then. However, I think that one of photography’s best tricks is the ability to mentally conjure the thing that you don’t show, as if the bowl were to contain just apple cores and banana peels. Sometimes a picture of what has been can be as powerful as freezing an event in progress. But that’s your choice.

Which is another of photography’s best tricks.

BEST OF TIMES, WORST OF TIMES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I OFTEN FANTASIZE ABOUT STANDING UP AND OFFERING A TOAST at a banquet hall crammed with photographers, just because it’s fun to play with what it might sound like….to see if I could strike some verbal chord that would resonate equally with everyone in the room, from the noobies to pro’s. I constantly change the exact wording, but the sentiment in my head is always something like:

May the best picture you took today be your worst picture ever, ten years from now.

What did he say? Does he hope the masterpiece I captured today will someday be regarded by me as garbage?

Well, yes, of course I do. At least I hope that for my stuff. If I still love today’s work ten years from now, it will mean that I stopped growing and learning, like, well, today. Consider: I can’t ever know everything about my craft, and can’t hope to “top out” or reach perfection within my lifetime. And why would I want to? If today is the best I’ll ever do, why not save time and money, smash my cameras, and consider myself done?

The entire point of artistic expression is that it is an evolutionary process. If I still took pictures the way I did at twelve, that would be like having been on a Ford assembly line for half a century, with one indistinguishable cog after another coming down the belt, and me adding the same screw to it, every day, for eternity. Photography appeals to us because, like any other measure of our mind, it will be in flux forever. It’s divinely uncertain.

And I want that uncertainty. I want the good shots that come on lousy days. I need the images that I made when I had no idea what I was doing. I crave the betrayals that camera bodies, lenses, changing weather conditions or cranky kids will hurl at me. Edward Steichen often referred to the act of refreshing one’s work as “kicking the tripod”, and, like that seismic shock, your own morphing ideas of how to do all this will benefit from an occasional earthquake.

Do great pictures always come from adversity? Of course not, or else my morbidly depressed friends would be the greatest photographers on earth. However, the sheer careening instability of life pretty much guarantees that the things that thrill you about today’s shots will make you shake your head ten years down the line, and devise different ways of solving all the eternal problems.

And so, a toast…to the great pictures you made today, and to the day that you can barely stand to look at them.

THE EYES HAVE IT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WINDOW TO THE SOUL: that’s the romantic concept of the human eye, both in establishing our emotional bonds with each other and, in photography, revealing something profound in portraiture. The concept is so strong that it is one of the only direct links between painting (the way the world used to record emotional phenomena) and photography, which has either imitated or augmented that art for two full centuries. Lock onto the eyes, we say, and you’ve nailed the essence of the person.

So let’s do a simple comparison experiment. In recent years, I’ve begun to experiment more and more with selective-focus optics such as the Lensbaby family of art lenses. Lensbabies are unabashedly “flawed” in that they are not designed to deliver uniform focus, but, in fact, use the same aberrations that we used to design out of lenses to isolate some subjects in intensely sharp areas ( so-called “sweet spots”) surrounded by gradually increasing softness.

As a great additional feature, this softness can even occur in the same focal plane as a sharply rendered object. That means that object “A”, five feet away from the camera, can be quite blurry, while object “B”, located just inches to the side of “A”, and also five feet from the camera, can register with near-perfect focus. Thus, Lensbaby lenses don’t record “reality”: they interpret mood, creating supremely subjective and personal “reads” on what kind of reality you prefer.

Exact same settings as the prior example, but with a slightly tighter focus of the Lensbaby’s central “sweep spot”.

Art lenses can accentuate what we already know about faces, and specifically, eyes…that is, that they remain vital to the conveyance of the personality in a portrait. In the first sample, Marian’s entire face takes on the general softness of the entire frame, which is taken with a Lensbaby Sweet 35 lens at f/4 but is not sharply focused in the central sweet spot. In the second sample, under the same exposure conditions, there is a conscious effort to sharpen the center of her face, then feather toward softness as you radiate out from there.

The first exposure is big on mood, with Marian serving as just another “still life” object, but it may not succeed as a portrait. The second shot uses ambient softness to keep the overall intimacy of the image, but her face still acts as a very definite anchor. You “experience” the picture first in her features, and then move to the data that is of, let’s say, a lower priority.

Focus is negotiated in many different ways within a photograph, and there is no empirically correct approach to it. However, in portrait work, it’s hard to deny that the eyes have it, whatever “it” may be.

Windows to the soul?

More like main clue to the mystery.

A THING OF THE MOMENT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CAN YOU TRAIN YOUR EYE TO SEE FASTER? Now, by “seeing”, I mean a process which effectively goes beyond the mere reception of light or visual information, something unique to the process of photography. I’m asking if you can, in effect, train the eye to, if not actually see faster, to more efficiently communicate with the brain and the hand in selecting what is important, so more rapidly apprehend the fleeting moment when a picture must be made.

I’m talking about the gradually learned trick of deciding quicker what you want and when it might be near at hand.

Much has been written about Henri Cartier-Bresson’s idea of “the decisive moment”, the golden instant in which viewpoint, conditions, and subject converge to be especially eloquent….to be, in effect, the only true artistic moment at which a photograph can be taken. Many reject this idea out of hand, saying that there are many potential great opportunities in the space of even a few seconds, and that the lucky among us grab at least one now and then. For those people, it’s not so much “the” moment as “a” moment.

Whatever the nature of the near-perfect shot is, sensing when one is imminent isn’t magic, and it isn’t accidental. It’s also not guaranteed by talent or luck. It has to be the result of experience, more specifically, lots of unsatisfying experience. Because I feel that the pictures you didn’t get are far more instructive than the ones you did, simply because you burn more brain cells on the mysteries of what went wrong than you do on the miracle of getting things right.

This image is neither the result of great advance planning nor of great fortune: it’s somewhere in the middle, but it does record an instant when everything that can work is working. The light, the contrasting tones of white and gray, the framing, the incidental element of the passing tourist….they were all registering in my mind at the precise instant before I snapped the frame.

This does not mean I was totally in charge of the process: far from it. But I knew that something was arriving, something that would be gone in less than a second. Also, the elements that were converging to make the image were also in flux, and, having moved on, would result in something very different if I were to take a second or third crack at the same material.

For a photographer, it’s a little like surfing. You take lots of waves, with the idea that any of them can deliver the ride of your life. But, on any given day, all of them could be duds. However (and this is the part about a trained eye), you can learn to spot the best waves faster and faster, converting more of them to great rides. And making pictures is much the same process. You can’t absolutely analyze what will make a picture work, but you can learn to spot potential quicker, on some level between intentional and accidental.