WHAT’S THIS I SEE?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS PHOTOGRAPHERS, WE HAVE A LIFETIME OF HEART-TO-HEART TALKS with ourselves, seeking the answer to questions like “what’s this I see?”, or “what do I want to tell?” Tricky thing is, of course, that, as time progresses, you are talking with a variety of conversational partners. As we age, we re-engineer nearly every choice-making process or system of priority. I loved Chef-By-Ar-Dee as an eight-year-old, but the sight of the old boy would probably make me gag at 63. And so it goes with clothing, choice of good reads, and, of course photography.

One of the things it’s prudent to do over the years is to take the temperature of present-day You, to really differentiate what that person wants in an image, versus what seemed essential at other stages in your life. I know that, in my case, my favorite photographers of fifty years ago bear very little resemblance to the ones I see as signposts today.

As a boy, I was in love with technical perfection and a very literal form of storytelling. Coming up in an artist’s household, I saw photos as illustrations, that is, subservient to some kind of text. I chose books for their pictures, yes, but for how well they visualized the writing in those books. The house was chock full of the mass-appeal photo newsmagazines of that day, from Life to Look to National Geographic to the Saturday Evening Post, periodicals that chose pictures for how well they completed the stories they decorated. A picture-maker for me, then, basically a writer’s assistant.

By my later school years, I began, slowly, to see photographs as statements unto themselves, something beyond language. They were no longer merely aids to understanding a writer’s position, but separate, complete entities, needing no intro, outro or context. The pictures didn’t have to be “about” anything, or if they were, it wasn’t a thing that was necessarily literal or narrative. Likewise, the kind of pictures I was interested in making seemed, increasingly, to be unanchored from reference points. Some people began to ask me, “why’d you make a picture of that?” or “why aren’t there any people in there?”

By this time in my life, I sometimes feel myself rebelling against having any kind of signature style at all, since I know that any such choice will eventually be shed like snake-skin in deference to some other thing I’ll deem important. For a while. What this all boils down to is that the journey has become more important than the destination, at least for my photography. What I learn is often more important than what I do about it.

And some days, I actually hope I never get where I’m going.

PRACTICE MAKES…?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

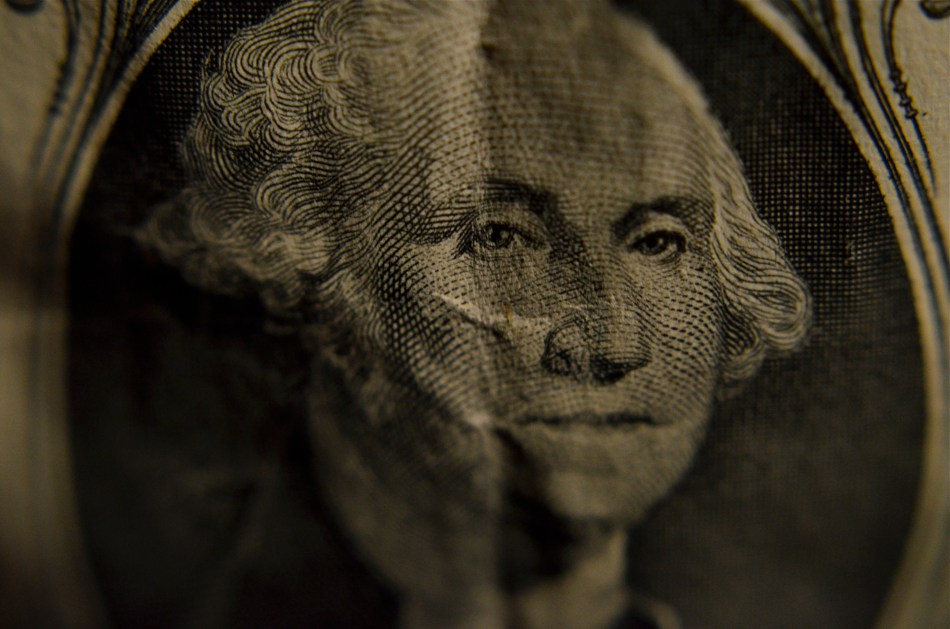

THE BEST SELLER LIST IS THE FASTEST WAY to cement a notion in the public’s mind as indisputable “fact”. We are great at quoting a concept captured in print, then re-quoting the quote, until the “truthfulness” of it becomes plausible. It’s basically a version of the statement, “everybody knows that..” followed by a maxim from whatever hardcover pundit is top in the rotation at a given moment. And it’s about as far from accuracy as you can get.

Ever since pop-psych guru Malcolm Gladwell’s hit book Outliers arrived on shelves a few years back, its main thesis, which is that you need 10,000 hours of practice to become excellent at something, has been trotted out a thousand times to remind everyone to just keep nose to grindstone and, well, practice will make perfect. Gladwell cites Bill Gates’ concentrated stretch of garage tinkering and the Beatles’ months of all-night stands in Hamburg as proof of this fact, and, heck, since it ought to be true, we assume it is.

However, it’s not so true as it is comfortable, and, when it comes to photography, I would never hint that someone could become an excellent artist just by putting in more time shooting than everyone else. If my method is wrong, if I never develop a vision of any kind, or if I merely replicate the same mistakes for the requisite practice period, then I am going to get to my goal older, but not wiser. Time spent, all by itself, is no indication of anything, except time spent. Evolving, constantly learning from negative feedback, and learning how to be your own worst critic are all better uses of the years than just filling out some kind of achievement-based time card.

The perfection of photography is about time, certainly, and you must invest a good deal of it to allow for the mistakes and failures that are inevitable with the acquiring of any skill. But, you must also stir insight, humility, curiosity and daring into the recipe or the end result is just mediocrity. Gladwell’s magical 10,000 hours, a quantity measurement, is only miraculous when coupled with an accompanying quality of work.

There are people who know how to express their soul on their first click of the shutter, just as there are those who slog away for decades and get no closer to imparting anything. It’s how well you learn, not how long you stay in school. It ain’t comforting, but it’s true.

YOU’RE GREAT, NOW MOVE, WILLYA?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF MY FAVORITE SONGS FROM THE ’40’s, especially when it emanates from the ruby lips of a smoking blonde in a Jessica Rabbit-type evening gown, conveys its entire message in its title: Told Ya I Love Ya, Now Get Out! The hilarious lyrics speak of a woman who acknowledges that, yeah, you’re an okay guy, but don’t get needy. No strings on me, baby. I’ll call you when I want you, doll. Until then, be a pal and take a powder.

I sometimes think of that song when looking for street images. Yes, I’m aware that the entire sweep of human drama is out there, just ripe for the picking. The highs. The lows. Thrill of victory and agony of de feet. But. I always feel as if I’m cheating the world out of all that emotional sturm und drang if I want to make images without, you know, all them people. It’s not that I’m anti-social. It’s just that compelling stuff is happening out there that occasionally only gets compromised or cluttered with humans in the frame.

Scott Kelby, the world’s biggest-selling author of photographic tutorials, spends about a dozen pages in his recent book Photo Recipes showing how to optimize travel photos by either composing around visitors or just waiting until they go away. I don’t know Scott, but his author pic always looks sunny and welcoming, as if he really loves his fellow man. And if he feels it’s cool to occasionally go far from the madding crowd, who am I to argue? There are also dozens of web how-to’s on how to, well, clean up the streets in your favorite neighborhood. All of these people are also, I am sure, decent and loving individuals.

There is some rationality to all this, apart from my basic Scrooginess. Photographically, some absolutes of abstraction or pure design just achieve their objective without using people as props. Another thing to consider is that people establish the scale of things. If you don’t want that scale, or if showing it limits the power of the image, then why have a guy strolling past the main point of interest just to make the picture “human” or, God help us, “approachable”?

Faces can create amazing stories, imparting the marvelous process of being human to complete scenes in unforgettable ways. And, sometimes, a guy walking through your shot is just a guy walking through your shot. Appreciate him. Accommodate him. And always greet him warmly:

Told ya I love ya. Now get out.

WHEN TEXTURE IS THE TALE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THOSE WHO BELIEVE THAT SUBJECT MATTER IS KING IN PHOTOGRAPHY ARE FACED OFF in an endless tennis match with those who believe that only impressions, not subjects, are the heart of the art. Go away for fifty or sixty years and they are still volleying: WAP! a photograph without an objective is a waste of time! WAP! who needs an object to tell a story? Emotional impact is everything! And so on. Pick your side, pick your battle, the argument isn’t going anywhere.

Thing is, my assertion is that you don’t actually have to choose a side. Just let the assignment at hand dictate whether subject or interpretation is your objective. There are times when the object itself provides the story, from a venerable cathedral to an eloquently silent forest. And there are times when mere color, light patterns, or texture are more than enough to tell your tale.

Set Your Face Like Flint, 2014. Shot wide at 18mm, cropped to square format. 1/100 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100.

I find, for example, that texture is one of my best friends when it comes to conveying a number of important things. The passage and impact of time. The feel and contour of materials, as well as the endless combinations and patterns they achieve through aging and weathering. A way to completely redefine an object by getting close enough to value its component parts instead of viewing it as a whole. This is especially true as I try to refine my approach to images of buildings. I find that breaking the overall structure into smaller, more manageable sections helps to amplify texture, to make it louder and prouder than it might be if a larger scene just included the entire building among other visual elements. Change the distance from your story and you change the story itself.

This Massachusetts barn has tons of character whether seen near or far, but if I frame it to eliminate anything but the raw feel of the wood, it demands attention in a completely different way. It asks for re-evaluation.Contrast the rough-sawn wood with the hard red of the windows,and, again, you’ve boosted the effect of the coarser texture. Opposing textures create a kind of rudimentary tug-of-war in a picture, and the more stark the contrasts, the more dramatic the impact.

Traditional, subject-driven story telling will dictate that you show the entire barn, maybe with surrounding trees and a rolling hill or two. Abstracting it a little in terms of color, distance and texture just tell the story in a distinct way. Your camera, your choice.

THE EYES (DON’T NECESSARILY) HAVE IT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

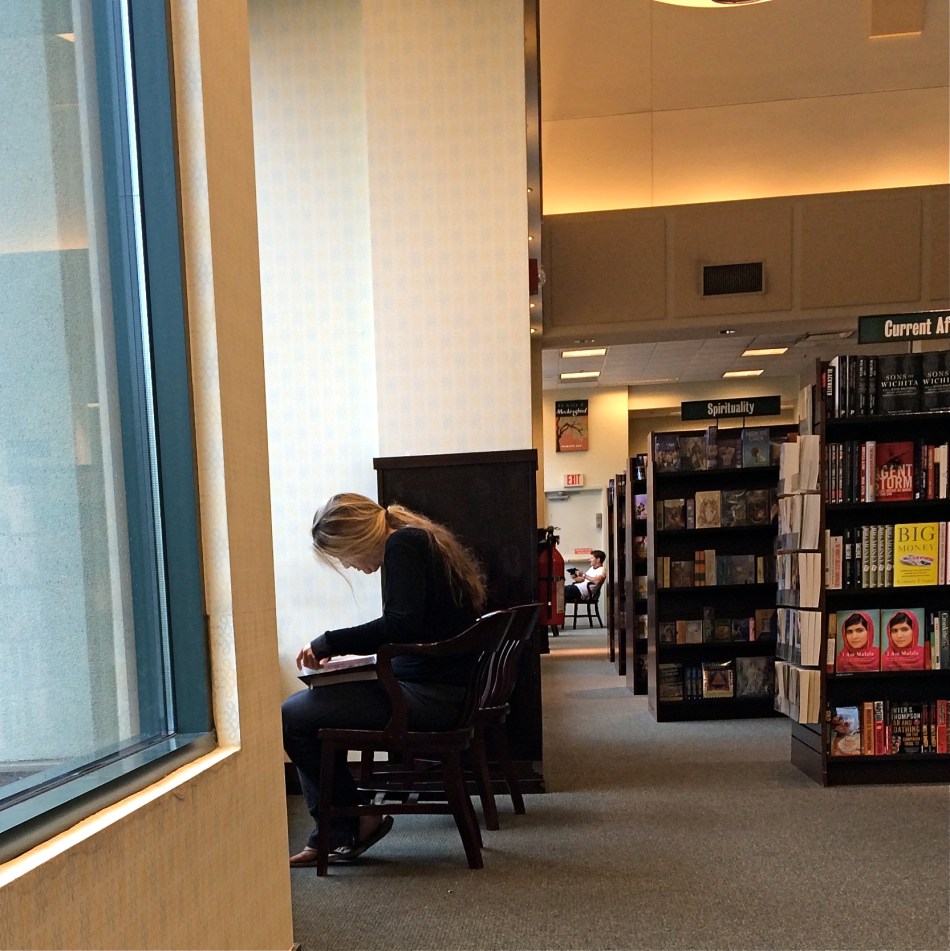

A QUICK GOOGLING OF THE PHOTOGRAPHIC UNIVERSE THESE DAYS will turn up a number of sites dedicated to “faceless portraits”, if there can, strictly speaking, be such a thing (and I believe there can). In a recent post entitled Private, Not Impersonal, I explored the phenomenon in which photographers, absent the features that most easily chronicle their subjects’ personalities, imply them, merely through body language, composition, or lighting. At the time I wrote the post, I was unaware how widespread the practice of faceless portraits had become. In fact, it’s something of a rage. Hmm. The very thought that, even by accident, I could be aligned with something hip, is, by turns, both terrifying and hilarious.

Thing is, photographs, as the famous curator John Szarkowki remarked, both conceal and reveal, and there is nothing about the full depiction of a human face that guarantees that you’re learning or knowing anything about the subject in frame. We are all to practiced at maintaining our respective masks for many portraits to be taken, ha ha, at face value. Cast your eye back through history and you will find dozens of compelling portraits, from Edward Steichen’s silhouettes of Rodin to Annie Leibovitz’ blurred dance photos of Diane Keaton, that preserve some precious element of humanity that a formal, face-on sitting cannot deliver. Call it mystery, for lack of a more precise word.

In the above frame, the subject whose face I myself never even saw gave me something wonderfully human, about reading in particular, but about enchantment in general. She is furiously busy discovering another world, a world the rest of us can only guess at, seeping up from her book. Her entire body is an inventory of emotional textures…of relaxation, attentiveness, of both being in the present and so completely someplace else. Framing her to include the negative spaces of the window, the carpet and the wider bookstore isolate her further from us, but not in a negative way. She wants to be apart; she is on a journey.

My “girl with the flaxen hair” was unaware of me, and I shot furtively and quickly to make sure I didn’t break the spell she was under. It was the least I could do in gratitude for a chance to witness her adventure. Looking back, I think she provided more than enough magic without revealing a single fragment of her face. Seeing is selecting, and I had been given all I needed to do both.

Click and be gone.

EYES WITHOUT A FACE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CHILDREN ARE THE GREATEST DISPLAY SPACES FOR HUMAN EMOTION, if only because they have neither the art nor the inclination to conceal. It isn’t that they are more “honest” than adults are: it’s more like they simply have no experience hiding behind the masks that their elders use with such skill. Since photographs have to be composed within a fixed space or frame, our images are alternatively about revelation and concealment. We choose how much to show, whether to discover or hoard. That means that sometimes we tell stories like adults, and sometimes we tell them like children.

The big temptation with pictures of children is to concentrate solely on their faces, but this default actually narrows our array of storytelling tools. Yes, the eyes are the window to the soul and so forth….but a child is eloquent with everything in his physical makeup. His face is certainly the big, obvious, electric glowing billboard of his feelings, but he speaks in anything he touches, anywhere he runs toward, even the shadows he casts upon the wall. Making pictures of these fragments can produce telling statements about the state of being a child, highlighting the most poignant, and, for us, the most forgotten bits.

Children are all about unrealized potential. Since nothing’s happened yet, everything is possible. Potential and possibility are twin mysteries, and are the common language of kids. Tapping into either one can provide the best element in all of photography, and that is the element of surprise.

BRING BACK THE SHOE BOX?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS WITH MOST REVOLUTIONS, THE FAIRLY RECENT ROCKET RIDE INTO THE DIGITAL DOMAIN has created a few casualties. There simply is no way to completely transform the very act of photography without also unleashing ripples into how we view and value the images we’ve created. One of the most frequently lamented losses along these lines has to do with holding a “hard copy” picture in your hand, of having a defined physical space in which they can be easily catalogued and viewed by all. In speaking with various people about this, I sense a real emotional disconnect, a pang that can’t be satisfied by knowing that the pictures are “somewhere out there” in cyberspace. We tossed away the old family photo shoe box in all its chaos, but a key human experience was also sacrificed along the way.

If you never take the time to review the thousands of images you shoot, you lose the joy of the occasional jewels and the lessons of the near misses.

One of the consequences of the end of film is the complete banishment of numerical barriers that used to keep our photographic output at a more controllable size. A roll of film held you to 24, maybe 36 exposures. You had to budget your shots. There were no instant do-overs, no chance to shoot bursts of 60 shots of Bobby kicking the soccer ball. Now we have an overabundance of choices in shooting, which, ironically, can be a little intimidating. We can produce so many thousands of pictures in a given year that our senses simply become overwhelmed with the task of sorting, editing, or prioritizing them. Gazillions of photos go into the cloud, many unseen past the first day they are uploaded. Our ability to organize our images in any comprehensible way has not kept pace with the technology used to capture them.

I truly feel that we have to work harder than ever, not on the taking of pictures, which has become nearly intuitive in its technical ease, but on the curating of what we’ve produced. For every five hours we spend shooting, I feel that fully half that time should be spent on the careful review of everything we’ve shot, not merely the quick “like/don’t like” card shuffle many of us perform when zipping through a large batch of captures. And this is not just for we ourselves. Think about it: how can our families and friends think of our photography as a visual legacy in the way we once regarded that shoe box if they have no real appreciation of what all is even in the new, virtual equivalent of that box? If it takes us months after we do a shoot to have even a rough idea of what resulted, we are missing the occasional jewel as well as the instructive power of the many near misses. That’s having an experience without availing yourself of any idea of what it meant, and that is crazy.

There is a reason that McDonald’s only offers Coke in three serving sizes. As consumers, we really crash into paralysis when presented with too many choices. We think we want a selection consisting of, well, everything, but we seldom make use of such overwhelming sensory input. I’m a huge fan of being able to shoot as many images as you need to get what will become your precious few “keepers”. But trying to keep everything without separating the wheat from the chaff isn’t art. It isn’t even collecting.

It’s just hoarding.

THINGS ARE LOOKING DOWN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY, AND THE HABITS WE FORM IN ITS PRACTICE, BECOME A HUGE MORGUE FILE OF FOLDERS marked “sometimes this works” or “occasionally try this”, tricks or approaches that aren’t good for everything but which have their place, given what we have to work with in the moment.

Compositionally, I find that just changing my vantage point is a kind of mental refresher. Simply standing someplace different forces me to re-consider my subject, especially if it’s a place I can’t normally get to. That means, whenever I can do something easy, like just standing or climbing ten feet higher than ground level, I include it in my shooting scheme, since it always surprises me.

For one thing, looking straight down on objects changes their depth relationship, since you’re not looking across a horizon but at a perpendicular angle to it. That flattens things and abstracts them as shapes in a frame, at the same time that it’s exposing aspects of them not typically seen. You’ve done a very basic thing, and yet created a really different “face” for the objects. You’re actually forced to visualize them in a different way.

Everyone has been startled by the city shots taken from forty stories above the pavement, but you can really re-orient yourself to subjects at much more modest distances….a footbridge, a step-ladder, a short rooftop, anything to remove yourself from your customary perspective. It’s a little thing, but then we’re in the business of little things, since they sometimes make big pictures.

TURN THE PAGE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’M VERY ACCUSTOMED TO BEING STOPPED IN MY TRACKS AT A PHOTOGRAPH THAT EVOKES A BYGONE ERA: we’ve all rifled through archives and been astounded by a vintage image that, all by itself, recovers a lost time.

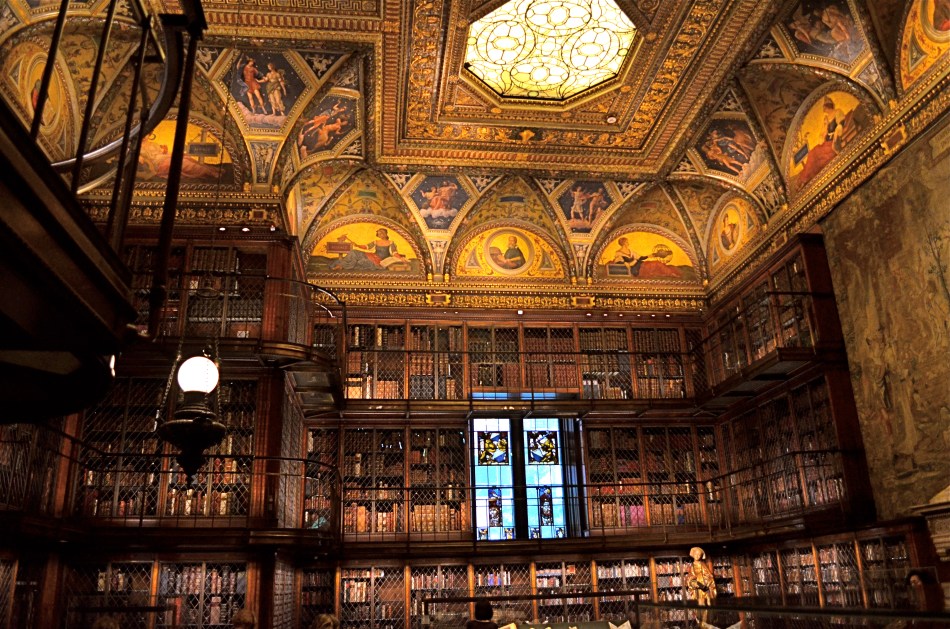

It’s a little more unsettling when you experience that sense of time travel in a photo that you just snapped. That’s what I felt several weeks ago inside the main book trove at the Morgan Library in New York. The library itself is a tumble through the time barrier, recalling a period when robber barons spent millions praising themselves for having made millions. A time of extravagant, even vulgar displays of success, the visual chest-thumping of the Self-Made Man.

The private castles of Morgan, Carnegie, Hearst and other larger-than-life industrialists and bankers now stand as frozen evidence of their energy, ingenuity, and avarice. Most of them have passed into public hands. Many are intact mementos of their creators, available for view by anyone, anywhere. So being able to photograph them is not, in itself, remarkable.

A little light reading for your friendly neighborhood billionaire. Inside the Morgan Library in NYC.

No, it’s my appreciation of the fact that, today,unlike any previous era in photography, it’s possible to take an incredibly detailed, low-light subject like this and accurately render it in a hand-held, non-flash image. This, to a person whose life has spanned several generations of failed attempts at these kinds of subjects, many of them due to technical limits of either cameras, film, or me, is simply amazing. A shot that previously would have required a tripod, long exposures, and a ton of technical tinkering in the darkroom is just there, now, ready for nearly anyone to step up and capture it. Believe me, I don’t dispense a lot of “wows” at my age, over anything. But this kind of freedom, this kind of access, qualifies for one.

This was taken with my basic 18-55mm kit lens, as wide as possible to at least allow me to shoot at f/3.5. I can actually hand-hold fairly steady at even 1/15 sec., but decided to play it safe at 1/40 and boost the ISO to 1000. The skylight and vertical stained-glass panels near the rear are WINOS (“windows in name only”), but that actually might have helped me avoid a blowout and a tougher overall exposure. So, really, thanks for nothing.

On of my favorite Twilight Zone episodes, the one about Burgess Meredith inheriting all the books in the world after a nuclear war, with sufficient leisure to read his life away, was entitled “Time Enough At Last”. For the amazing blessings of the digital age in photography, I would amend that title by one word:

Light Enough…At Last.

ALIENATIONS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE STRANGEST VISUAL EVIDENCE OF MAN’S PRESENCE ON THE PLANET IS HIS ABILITY TO COMPARTMENTALIZE HIS THINKING, the ability to say, of his living patterns, “over here, cool. Over there, six inches away, ick. You see these kind of yes/no, binary choices everywhere. The glittering, gated community flanked by feral urban decay. The open pasture land that abuts a zoo. And the natural world, trying desperately to be heard above the roar of its near neighbors from our co-called “civilization”.

As seen from Griffith Observatory: park running paths and a smog-shrouded L.A. 1/320 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

I recently re-evaluated this image of the running paths at Los Angeles’ Griffith Park and the nearby uber-grid of the central city. The colors are a bit muted since it was taken on a day of pretty constant rolling overcast, and it really is not a definitive portrait of either the city or the nearby greenspace, but there is a little story to be told in the ability of the two worlds to co-exist.

L.A’s lore is rife with stories of destroyed environments, twisted eco-structure, bulldozed neighborhoods and political hackery advanced at great cost to the poor and the powerless. In the face of that history, the survival of Griffith, a 4,310-acre layout of parks, museums, kiddie zoos, sports courts, and concert venues on the eastern end of the Santa Monica Mountains, is something of a miracle. It’s the lion lying down with the lamb, big-time, a strange and lucky juxtaposition that affords some of the most interesting fodder for photographers anywhere in California. Photogs observe natural pairings in the world, but they also chronicle alienations, urban brothers from different mothers, tales of visual conflicts that, while they can’t be reconciled, are worth noting.

FRONT TO BACK

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NOT ALL PORTRAITS INVOLVE FACES.

I’ll let that little bit of blasphemy sink in for a moment. After all, the face is supposed to be the key to a persona’s entire identity, and God knows that many a mediocre shot has been saved by a fascinating expression, right? The eyes are the window to the soul, and so on, and so forth, etc., etc.

But is this “face-centric” bias worthy of photographers, who are always re-writing the terms of visual engagement on every conceivable subject? Is there one single way to make a person register in an image? Obviously I don’t believe that, or else I wouldn’t have started this argument, but, beyond my native contrariness, I just am not content with there being a single, approved way of visualizing anything. I’ve seen too much amazing work done from every conceivable standpoint to admit of any limitation, or need for a “rule”, even when it comes to portraiture.

The face is many things, but it’s not the entire body, and even if you capture a shot in which the subject’s face is absent, he or she can be so very present in the feel of the picture. Arms, shoulders, the sinews, the stance, the way a body stands in a frame…all can bear testimony.

I recently stumbled onto an impromptu performance by a young string quartet, and faced the usual problem of not being able to simultaneously do justice to all four members’ faces, to balance the tension and concentration written on all their features in performance. In such situations, you have to make some kind of call: the picture becomes a dynamic tension between the shown and the hidden, just as the music is a push-and-pull between dominant and passive forces. You must decide what will remain unseen, and, sometimes, that’s a face.

As the music evolved, the two ladies seen above were, in different instants, either in charge of, or at the service of, the energy of the moment. For this picture, I saw more strength, more power in the back of the violinist than in the front of the cellist. It was body language, a kind of structural tug between the pair, and I voted for what I could not show fully. As it turned out, the violinist actually has a lovely face, one possessing a stern, disciplined intensity. On another day, her story would have been told very differently.

On this day, however, I was happy to have her turn her back on me.

And turn my own head around a bit.

WORK AT A DISADVANTAGE

Focus. Scale. Context. Everything’s on the table when you’re trolling for ideas. 1/100 sec., f/5.6, ISO 800, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“IS THERE NO ONE ON THIS PLANET TO EVEN CHALLENGE ME??“, shouts a frustrated General Zod in Superman II as he realizes that not one person on Earth (okay, maybe one guy) can give him a fair run for his money. Zod is facing a crisis in personal growth. He is master of his domain (http://www.Ismashedtheworld.com), and it’s a dead bore. No new worlds to conquer. No flexing beyond his comfort zone. Except, you know, for that Kryptonian upstart.

Zod would have related to the average photographer, who also asks if there is “anyone on the planet to challenge him”. Hey, we all walk through the Valley Of The Shadow Of ‘My Mojo’s Gone’. Thing is, you can’t cure a dead patch by waiting for a guy in blue tights to come along and tweak your nose. You have to provide your own tweak, forcing yourself back into the golden mindset you enjoyed back when you were a dumb amateur. You remember, that golden age when your uncertainly actually keened up your awareness, and made you embrace risk. When you did what you could since you didn’t know what you could do.

You gotta put yourself at a disadvantage. Tie one hand behind your back. Wear a blindfold. Or, better yet, make up a “no ideas” list of things that will kick you out of the hammock and make you feel, again, like a beginner. Some ways to go:

1.Shoot with a camera or lens you hate and would rather avoid. 2.Do a complete shoot forcing yourself to make all the images with a single lens, convenient or not. 3.Use someone else’s camera. 4.Choose a subject that you’ve already covered extensively and dare yourself to show something different in it. 5.Produce a beautiful or compelling image of a subject you loathe. 6.Change the visual context of an overly familiar object (famous building, landmark, etc.) and force your viewer to see it completely differently. 7.Shoot everything in manual. 8.Make something great from a sloppy exposure or an imprecise focus. 9.Go for an entire week straight out of the camera. 10.Shoot naked.

Okay, that last one was to make sure you’re still awake. Of course, if nudity gets your creative motor running, then by all means, check local ordinances and let your freak flag fly. The point is, Zod didn’t have to wait for Superman. A little self-directed tough love would have got him out of his rut. Comfort is the dread foe of creativity. I’m not saying you have to go all Van Gogh and hack off your ear. But you’d better bleed just a little, or else get used to imitating instead of innovating, repeating instead of re-imagining.

GOING (GENTLY) OFF-ROAD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN YOU’RE BEHIND THE WHEEL, SOME PHOTOGRAPHS NAG THEIR WAY INTO YOUR CAMERA. They will not be denied, and they will not be silenced, fairly glowing at you from the sides of roads, inches away from intersections, in unexplored corners near stop signs, inches from your car. Take two seconds and grab me, they insist, or, if you’re inside my head, it sounds more like, whatya need, an engraved invitation? Indeed, these images-in-waiting can create a violent itch, a rage to be resolved. Park the car already and take it.

Relief is just a shutter away, so to speak.

The vanishing upward arc and sinuous mid-morning shadows of this bit of rural fencing has been needling me for weeks, but its one optimal daily balance of light and shadow was so brief that, after first seeing the effect in its perfection, I drove past the scene another half dozen times when everything was too bright, too soft, too dim, too harsh, etc., etc. There was always a rational reason to drive on.

Until this morning.

It’s nothing but pure form; that is, there is nothing special about this fence in this place except how light carves a design around it, so I wanted to eliminate all extraneous context and scenery. I shot wide and moved in close to ensure that nothing else made it into the frame. At 18mm, the backward “fade” of the fence is further dramatized, artificially distorting the sense of front-to-back distance. I shot with a polarizing filter to boost the sky and make the white in the wood pop a little, then also shot it in monochrome, still with the filter, but this time to render the sky with a little more mood. In either case, the filter helped deliver the hard, clear shadows, whose wavy quality contrasts sharply with the hard, straight angles of the fence boards.

I had finally scratched the itch.

For the moment….

ASSISTANTS AND APPROACHES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHO CAN SAY WHY SOMETHING CALLS OUT TO US VISUALLY? I have marveled at millions of moments that someone else has chosen to slice off, isolate, freeze and fixate on, moments that have, amazingly, passed something along to me in their photographic execution that I would never have slowed to see in the actual world. It’s the assist, the approach, if you will, of the photographer that makes the image compelling. It’s the context his or her eye imposes on bits of nature that make them memorable, even unforgettable.

It’s occurred to me more than once that, given the sheer glut of visual information that the current world assaults us with, the greatest thing a photographer can do is at least arrest some of it in its mad flight, slow time enough to make us see a fraction of what is racing out of our reach every second. I don’t honestly know what’s more fascinating; the things we manage to freeze for further consideration, or the monstrous ocean of visual data that is lost, constantly.

There’s a reason photography has become the world’s most loved, hated, trusted, feared, and treasured form of storytelling. For the first time in human history, these last few centuries have afforded us to catch at least a few of the butterflies of our fleeting existence, a finite harvest of the flurrying dust motes of time. It’s both fascinating and frustrating, but, like spellbound suckers at a magic show, we can’t look away, even when the messages are heartbreaking, or horrible.

We are light thieves, plunderers on a boundless treasure ship, witnesses.

Assistants to the seeing eye of the heart.

It’s a pretty good gig.

RESOLVED

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS A DECIDED BIAS IN THE CONCEPT OF THE NEW YEARS’ RESOLUTION TOWARD THE NEGATIVE. Since we often define ourselves in terms of what we haven’t yet perfected in ourselves, many resolutions revolve around losing something (weight), stopping something (binge-watching Ren & Stimpy) or rooting something icky out of our personality or habit structure (insert your own wish list here).

Fair enough. But, in order for us to grow, we also need to resolve to add, to enhance, to amplify the best part of ourselves. And, for photographers, I can’t think of a single more compelling resolution than the pledge to see better and develop our expressive vocabulary in the new year. We already have the toys, God knows. It has never been easier to get your hands on image-making gear or to disseminate the images that you manage to create. Photography has reached its all-time high-water mark for democratization, with 2013 showing us that gasp-inducing, heart-stopping pictures can and will be made by anyone, anywhere. There is no longer an artificial barrier between pro and amateur, just a subtler one between those of us who have practiced eyes and those of us (nearly all of us) that need to tone our seeing muscles a bit tighter.

Photography can obscure or reveal, defining or defying clarity as we choose. A resolution to keep seeing, to open our eyes wider, is more important than resolving to “take more interesting pictures”, “do fewer self-indulgent selfies” or “try all the cool filters on Instagram”, since it goes to the heart of what this marvelous art can do better than any other in the history of mankind. What can be better than promising ourself to always be hungry, always be shooting, always be straining ourselves to the breaking point?

For me, a good year is when I can look back over my shoulder during the last waning moments of December 31st and see at least some small, measurable distance between where I’m standing and where I stood last January 1st. Sometimes the distance is measured in micro-inches, other years in feet or even yards. There are no guarantees, nor can there be: human experience, and what we draw forth from it, is variable, and there will be years of no crops as well as years of bumper harvests.

But let us resolve to see, and see as fearlessly as we can. The Normal Eye has always been about its stated journey from “taking” pictures to “making” them, acknowledging that it’s seldom a straight-line path to perfection, and, in fact, we learn more from our failures than our successes. Happy New Year.

KICK-STARTING THE ENGINE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE POPULAR IMAGE OF A BLOCK-STRICKEN WRITER HELPLESSLY STARING AT A BLANK PAGE is enough to send an empathetic chill up the spine of anyone who has ever been haunted by a deadline or stymied by a narrative suddenly gone dry. And I am convinced, as both a writer and a photographer, that there is an equivalent “block” lurking in the shadows for any shooter, a visual desert that produces stretches of formless, pointless images, dry spells that are terrifying because they are open-ended. No one knows why, for everyone from time to time, the pictures stop coming, and no one can predict when they will come back.

It’s terrifying, because it’s as if vision or imagination were accounts that one can overdraw, bouncing artistic checks all over town and leaving you feeling, like Alice, that there is no bottom, only more hole. At least it’s terrifying to me.

Torchlight Parade, 12/14/13. 1/40, f/2.5, ISO 1000, 35mm. You work your way through dry spells with what’s at hand.

As I write this, I have just come off several weeks of scrapings and scraps that should have been photographs but instead are equivalent to something smeared by an ape on his cage wall. I have seldom experienced such an extended period of mega-nothing, and it is only my unswerving oath to myself to shoot something, anything, every single day, that has allowed me to keep faith with the inevitable return of whatever eye I sometime possess. But, I have to admit, I am also suppressing strong urges to, like Norman Bates, lock my camera inside a car trunk and seek out the nearest swamp.

Okay, that’s a tad dramatic, but my current case of the “drys” is unnerving for a particular reason. I am typically able to conjure pictures out of nearly nothing, which is more liberating than having to wait for obvious or “big” projects. You can shoot daily if you can get off on still lifes of plastic spoons. You can’t shoot daily if you need a vacation, a birthday, or a mountain for inspiration. So it’s doubly troubling if you can’t even summon up the humble crumbs needed for some kind of image.

I know, that, at one point or another, something will demand my attention/obsession, and we’ll be off to the races again. But there is always the nagging question. What happens if I can’t kick-start the engine? Everything has a beginning and an end. So…?

Oh, wait, the light is doing something really cool just now…..

DO SOMETHING MEANINGLESS

The subject matter doesn’t make the photograph. You do. A pure visual arrangement of nothing in particular can at least teach you composition. 1/400 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SHOOT WHAT YOU KNOW. SHOOT WHAT YOU LOVE. Those sentences seem like the inevitable “Column A” and “Column B” of photography. And it makes a certain kind of sense. I mean, you’ll make a stronger artistic connection to subject matter that’s near and dear, be it loved ones or beloved hobbies, right? What you know and what you love will always make great pictures, right?

Well….okay, sorta. And sorta not.

I hate to use the phrase “familiarity breeds contempt”, but your photography could actually take a step backwards if it is always based in your comfort zone. Your intimate knowledge of the people or things you are shooting could actually retard or paralyze your forward development, your ability to step back and see these very familiar things in unfamiliar ways.

Might it not be a good thing, from time to time, to photograph something that is meaningless to you, to seek out images that don’t have any emotional or historical context for you? To see a thing, a condition, a trick of the light just for itself, devoid of any previous context is to force yourself to regard it cleanly, without preconception or bias.

Looking for things to shoot that are “meaningless” actually might force you to solve technique problems just for the sake of solving, since the results don’t matter to you personally, other than as creative problems to be solved. I call this process “pureformance” and I believe it is the key to breathing new life into one’s tired old eyes. Shooting pure forms guarantees that your vision is unhampered by habit, unchained from the familiarity that will eventually stifle your imagination.

This way of approaching subjects on their own terms is close to what photojournalists do all the time. They have little say in what they will be assigned to show next. Their subjects will often be something outside their prior experience, and could be something they personally find uninteresting, even repellent. But the idea is to find a story in whatever they approach, and they hone that habit to perfection, as all of us can.

Just by doing something meaningless in a meaningful way.

JUST SAY THANK YOU

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PICTURES HAPPEN WHEN YOU’RE OUT TRYING TO TAKE “OTHER” PICTURES. Pictures happen when you didn’t feel like taking any pictures at all. And, occasionally, the planets align perfectly and you hold something in your hand, that, if you are honest, you know you had nothing to with.

Those are the pictures that delight and haunt. They happen on off-days, against the grain of whatever you’d planned. They crop up when it’s not convenient to take them, demanding your attention like a small insistent child tugging at your pants leg with an urgent or annoying issue. And when they call, however obtrusively, however bothersome, you’d better listen.

Don’t over-think the gift. Just say thank you….and stay open.

This is an overly mystical way of saying that pictures are sometimes taken because it’s their time to be taken. You are not the person who made them ready. You were the person who wandered by, with a camera if you’re lucky.

I got lucky this week, but not with any shot I had set out on a walkabout to capture. By the time I spotted the scene you see at the top of this post, I was beyond empty, having harvested exactly zip out of a series of locations I thought would give up some gold. I couldn’t get the exposures right: the framing was off: the subjects, which I hoped would reveal great human drama, were as exciting as a bus schedule.

I had just switched from color to monochrome when I saw him: a young nighthawk nursing some eleventh-hour coffee while poring over an intense project. Homework? A heartfelt journal? A grocery list? Who could tell? All I could see, in a moment, was that the selective opening and closing of shades all around him had given me a perfect frame, with every other element in the room diffused to soft focus. It was as if the picture was hanging in the air with a big neon rectangle around it, flashing shoot here, dummy.

My subject’s face was hidden. His true emotion or state of mind would never be known. The picture would always hide as much as it revealed.

Works for me. Click.

Just like the flicker of a firefly, the picture immediately went away. My target shifted in his chair, people began to walk across the room, the universe changed. I had a lucky souvenir of something that truly was no longer.

I said thank you to someone, packed up my gear, and drove home.

I hadn’t gotten what I originally came for.

Lucky me.

related articles:

- Crop and turn a bad picture into a good one (weliveinaflat.wordpress.com)