THE ABCs OF TMI

This street shot from a park in lower Manhattan is not ready for prime time, but it might get there with creative cropping.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR ME, ONE OF THE GREATEST ANCILLARY BENEFITS of doing historical research has been the privilege of poring over old files of newspaper and magazine photographs, in many cases viewing original, pre-publication master shots. It’s truly an exercise in reading between the “lines”, those hurried slashes of white grease pencil applied by editors as cropping instructions on shots that were too big, too busy, too slow in getting to the point. In many cases, you realize that, while the photographer may have taken the picture, it was the editor who found the picture.

Of course, no amount of cutting can improve a shot if there is not already a core story hiding within it. You can pare away the skin and seed of an apple, but some apples prove themselves rotten through and through. It’s the same with a photograph. However, if you teach yourself how to spot what, within a frame, is fighting with the central strength of a photo, it becomes obvious where to wield your scissors.

In the master shot image at top, the symmetry of the left and right groups of park visitors is blunted in its effect by the unneeded information along the top and bottom thirds of the frame. The shot is not really about the museum in the distance nor the ground in front of the benches. They just don’t help the flow of the picture, so losing them seems like the easiest way to boost the overall composition.

Now the shot is essentially a wide-angle, and, absent the earlier distractions, a kind of horseshoe curve emerges, tying the two benches together. You might even think of it as an arch shape, with the walking woman at the top acting as a keystone. She now draws attention first to the center, then around the curve, so that getting people to see what I am seeing becomes a lot easier. Finally, there is still a very loud distraction from the color in the shot, so a black-and-white remix keeps the reds and louder colors from “showing off” and lessening the impact of the story. The final result is still no masterpiece, but it does demonstrate that there was a very different picture hiding within the master shot, one that was certainly worth going after.

One of the downsides of being an amateur shooter is not reaping the benefit of a ruthless photo editor. However, learning to spot the weaknesses in potentially effective shots can be learned, most importantly the “ruthless” part. If you believe in an image, you won’t shy away from trimming its fingernails a bit to give it a chance to shine.

THE FAULT IN OUR DEFAULT

Potential nightmare: uneven light and wildly varied contrast. But I can save this shot because I can take direct control of camera settings.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CHILDREN THINK THAT HAPPINESS RESIDES IN ALWAYS BEING TOLD “YES”. Of course anyone who has ever (a) been a child or (b) had to deal with one knows that this is actually the worst of strategies. Even without being Tiger Moms, we can all pretty much agree that there are many times when telling a kid “NO” will improve, perhaps even save, his life. Negative responses carry important information. They can be guidelines. Most importantly, they convey that there are limits, consequences.

“NO” also helps you be a better photographer.

In the ’60’s, one of the most basic cameras ever sold, the teen-marketed Polaroid Swinger, had a shutter that you pinched to check if you had enough light to make a picture. If the word “YES” appeared in the viewfinder, you were solid. “NO”, given the simplicity of the gadget, meant, sorry, point this thing somewhere toward, you know, actual light. Easy. Unmistakable. Take the picture with a “NO”, and it’s on you.

Similar light conditions to the scene shown above, but now the phone camera has decided for me, to jack up the ISO, degrading the image. And there wasn’t a thing I could do to prevent it.

DSLR’s still flash a similar warning. With Nikon it’s “subject is too dark”. But the camera isn’t a mean parent that won’t let you choose ice cream over asparagus. It’s being a good parent that’s trying to give you a happy outcome. By contrast, smartphone cameras are bad parents. They never tell you “no”. If anything, their attitude is, point anywhere you like, anytime you like, darling. Mommy will still make a picture for you. That’s because the emphasis of design and use for smartphones is: make it simple, give the customer some kind of result, no matter what. You push the button, sweetheart, and we’ll worry about all that icky science stuff and give you a picture (image at left).

The default function of smartphone cameras is wondrous. You get a picture, every damn time. Never a blank screen, never a “no”. But in low-light situations, to accomplish this, the camera has to jack up the ISO to such a ridiculous degree that noise goes nuclear and detail goes buh-bye. The device has been engineered to make you happy over everything else, and its marketers have determined that you’d rather have a technically flawed picture than no picture, so that’s the mission. And that guarantees that your photography will linger in Average-land pretty much forever.

With iPhones, you have no override. You have no thumbs-up-thumbs-down decision. You have, actually, no input at all except your choice of subject and composing style. Now, you may think that this “frees” you, with the camera “getting out of your way”, and all, but it really means that, even if you have a better idea for making an image than your camera does, you cannot act upon it. Cameras that say “NO” are also saying, “but if you try something else, you will get to “YES” (image at top). Cameras that only say “YES” are really saying, “I know best. Leave it to me.”

Which of course, is something you heard all the time, years ago.

When you were a child.

LESS STILL, MORE LIFE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHIC HISTORIANS WILL PROBABLY CRINGE AT MY OVER-SIMPLIFICATION, but I tend to believe that still-life compositions were originally popular to shooters because they solved a technical problem. At the dawn of the imaging art, recording media, from salted paper to glass plates, were so abysmally slow that exposure times stretched, in some cases, to nearly an hour. This meant that subject matter with any kinetic quality, from evolving landscapes to a baby’s face, were rendered poorly compared to inanimate objects. Still lifes were not so much about the beauty and color of fruit and cheese on a plate as they were about practicing…learning how to harness light and deliver a desired effect.

As film and lenses both sped up, a still life could be chosen purely on its aesthetic appeal, but the emphasis was still on generating a “realistic” image…an imitation of life. The 20th century cured both photography and painting of that narrow view, and now a still life, at least to me, offers the chance to transform mundane material, to force the viewer to re-imagine it. You can do this with various processes and approaches, but the main appeal to me is the chance to toss the object out of its native context and allow it to be anything…or nothing.

In the image at left, the home-grown vegetables, seen in their most natural state, actually have become alien to our pre-packaged notions of nutrition. They don’t even look like what arrives at many “organic” markets, much less the estranged end-product from Green Giant or Freshlike. And so we are nearly able to see these vegetables as something else. Weeds? Flowers? Decay? Design? Photographing them in our own way, we are free to assign nearly any quality to them. They might, for example, be suggestive of a floral bouquet, a far cry from the edibles we think we know. Still life compositions can startle when they are less “still” and more “life”, but we have to get away from our subjects and approach them around their blind side.

As always, it’s not what we see, but how.

WHEN THE WALL IS ALL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

COLOR, IN REAL LIFE DOES NOT RESEMBLE SOMETHING FLATLY FILLED IN BY A CRAYON. Light never plays across surfaces in an even, unbroken tone, so, in a photograph, there really is no such thing as a “blue” wall, or a “brown” floor. Both the wall and the floor contain endless varieties and gradations of their general hue, changing inch to inch, atom by atom. Wonderfully, photography has been on a continuous upward curve over time to record these variances with better and better fidelity. As a result, we don’t just shoot tone, we shoot texture.

One way to heighten the registry of those textures, those colors-within-colors along a surface, is to vary the amount of light that hits it at different points. There’s a reason why Rembrandt and other masters of the “Dutch-lit” school used minimal or irregular light to illuminate their subjects. Light playing unevenly over fruit and the human form was simulated in their paintings by pigment colors that shimmered and smoldered: had they painted colors in a flat, uniform tone it would have read as dull as dishwater and Rembrandt and the other little daubed Dutch boys would have had to get day jobs.

In photographs, sometimes texture emits such a powerful visual impact that it’s enough to carry an entire image with little or no other subject matter. In the above picture, watching the window light at the right of the frame decay gradually as it “walks” across the distressed wall actually speaks louder than the solitary couple at the upper-right-hand corner. In such a picture, the wall becomes all, the changing colors highlighting small detail in the concrete and brick.

As usual, I learn a great deal by looking at how other people address this phenomenon. There are so many astounding ways to harness even a small bit of light via photography as it exists right now, and the best thing is, things will only improve from here, for anyone shooting at any level.

THE TAKEAWAY

The girl bathed in ceiling light is a nice start, but this picture needs some help to get where it’s going.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT IS SAID THAT THE GODDESS ATHENA WAS BORN, FULLY GROWN AND ARMORED, out of the forehead of Zeus. Other than being the only case where a man experienced anything that approached labor pain, the story always reminds me that ideas rarely arrive in their final form, especially in photography. If Athena had a Leica, she probably could have taken perfect shots without needing to compose or plan. We mere mortals are forced to either (a) report to hate-crazed photo editors, or (b) learn how to crop.

Many shots are created in stages, and there’s no shame in the game, since our original conception undergoes many phases from the first spark to something we’d actually hang on a wall. Creation itself is a process, which is why photographers should actually embrace the stages their work will pass through. The more thought that is applied to making an image, the better chance that the best way of doing something will reveal itself. Of course, it can also reveal the fact that there is nothing really to work with, in which case, hey, the bar should be open now, let’s go lick our wounds.

The original shot shown above is not yet a good photograph, but a good beginning for a  photograph. The lady bathed in light seems certainly to have been pre-selected to be the focal point of the picture, but there are way too many competing elements around her, robbing her of the prominence she deserves in the final frame. So let’s get after it.

photograph. The lady bathed in light seems certainly to have been pre-selected to be the focal point of the picture, but there are way too many competing elements around her, robbing her of the prominence she deserves in the final frame. So let’s get after it.

First, none of the information on the left side of the frame makes it any clearer that she’s alone or that she’s on the second floor of the building. We can make that plain with half the acreage, so snip. Similarly, the guys in shadow to her right aren’t part of the story we are crafting for her. If she’s isolated, let’s make her isolated and be unmistakable about it. She’s “apart” already from the sea of people below her. She’s geographically and physically separated from them, but the extra guys make the argument weaker, so, snip, away they go.

Finally, the entire upper-floor/lower-floor line of sight will be accentuated if we crop for a portrait orientation and move the frame so she is on the upper-right-hand corner of it. It forces the eye to discover the story of the picture vertically, so snip and we’re done.

So, at the end, we did not make any changes via processing, only the old scissors. Taking things away, not adding them on, actually made the picture work better. Fate gave me the girl and the wonderful light she was bathed in, but there was work to do. She didn’t arrive, ready to party, like Athena, but she’s a little closer to goddess status after some adjustment.

WHOOPS. YAY.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE A THEORY THAT “SERENDIPITY” is just “dumb luck” for pretentious people. Somehow it makes our random discoveries and unplanned miracles sound cooler if we attribute them to some grand lining-up of the planets, as if we apes really meant to discover fire. So, fine. Consider this an incident of serendipity, although it’s mainly a case of “I stepped in sugar instead of….” well, you get the idea.

Setting the scene: a suburban mall near me recently closed its enormous bookstore, applying a dark sheet of tint on the building’s huge windows so gawkers couldn’t spy on the joint’s sad makeover as a furniture store. Of course, if you want to make people curious about something, blacking out the windows is a pretty effective tactic, and there are always plenty of people smashing their faces up against the impermeable tint every day to see what a bookstore looks like when it has, you know, no books in it. I am usually first in line for this ritual.

For some reason this week, a small peephole has been opened in the sheeting, allowing one to see the place’s vast, empty floor, its draped escalator, and an iron tangle of scaffolding, as well as a huge infusion of light from an open-work area at the opposite side of the store. It isn’t quite the “ruin porn” that photographers of dead malls love to record just ahead of the wrecking ball, but eerie enough to make me want to shove my phone camera up against the peephole to try to capture it.

Given the very wide-angle of such devices, however, I discovered, after the click, that the lens had also picked up a portion of the window next to the peephole, a portion still covered by tint and capable of reflecting the scene behind me….various buildings and landscaping of the rest of the mall. Even stranger, the “other” reality behind me melded, through the blurred outline of the peephole and variances of light, with the scene inside the store, as if they were all part of one dreamy landscape, a Hollywood set in transition. Giddy at what I had grabbed by accident, I shot a second frame to compose things a bit better, then converted it to monochrome with a filter that simulates a platinum print effect, an effort to eliminate mismatches in color and tone between the two worlds.

Sinatra once said that “the professional is the guy who can do it more than once”, so this image ranks me solidly among the amateurs. But so what. Whoops. Yay.

GOING NEGATIVE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I got plenty of nothin’, and nothin’s plenty for me. —Ira Gershwin, Porgy and Bess

I BELIEVE THAT MANY PHOTOGRAPHS ARE IMPROVED BY THE SIMPLEST OF MATH OPERATIONS: addition and subtraction. Look at nearly any image you’ve created that “worked” and you can see that there is not one more thing in the image than there needs to be. Something told you to either supply or eliminate elements in the composition until the impact of the picture was maximized. Realizing the reverse effect is pretty easy as well, although not as much fun. If there is one tree too many or one object too few in the frame, you can sense the imbalance in your near-miss pictures. And man, does that hurt.

We used to refer to open areas of a picture as “blank” space, and were often talked out of using it at all by various A-B-C composition tutorials that told us that large expanses of sky could kill a good landscape. Today, we refer to this unused real estate as “negative” space, but we are now more inclined to see it as well, a positive thing. The take-home from this is, simply, that no technique should be universally ruled out, or ruled in, for every image. Truth is, there are times when not filling the frame with stuff, or selectively making use of negative space boosts the wattage of what you’re trying to say.

We used to refer to open areas of a picture as “blank” space, and were often talked out of using it at all by various A-B-C composition tutorials that told us that large expanses of sky could kill a good landscape. Today, we refer to this unused real estate as “negative” space, but we are now more inclined to see it as well, a positive thing. The take-home from this is, simply, that no technique should be universally ruled out, or ruled in, for every image. Truth is, there are times when not filling the frame with stuff, or selectively making use of negative space boosts the wattage of what you’re trying to say.

Instead of “negative” space, I prefer the term “secondary space”, since what you’re really doing is mapping your pictures into zones of the things that should be of primary interest and those that should complement those things without competing with them. Landscapes are the easiest way to demonstrate this. In the image at left, I wanted to accentuate the distance between the foreground tree and the background mountain. Framing the two elements to merely overlap gave no sense of space, and, in color, actually made the photo busy and hard to read. There seemed to be no primary object in the frame. Composing so that some sky intervened to the right of the tree and the top of the mountain re-established the sense of distance and kept the textures of both objects from fighting with each other.

Secondary space need not be empty. It can take the form of a texture, be it a body of water, cloud formations, a flooring pattern, or a stone wall. The idea is to use the space to support, but never upstage the primary space. Sometimes what you need to complete an image is nothing. You just have to stick the nothing in the right place.

CHOOSE THE INCONVENIENT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MARKETING BEING WHAT IT IS, CAMERA MANUFACTURERS HAVE LONG TOLD US THEY ARE DOING ONE THING FOR US when they are actually doing something very different. Since the first furry, day-long exposures of the 1800’s gave us a taste of what an entirely new medium could do in the way of chronicling the world, we have been promised that, over succeeding generations of technical development, taking a picture would get easier. In fact, this is a little inaccurate, as what the wizards have mostly done is to make taking a picture faster.

If this sounds like I’m splitting a sub-atomic-sized hair, hear me out. Many of the refinements in camera design over the last century and a half have, of course, improved the sharpness of lenses, the absorbance quotient of recording media, and enhanced design. However, the lion’s share of reboots have been to require fewer steps in framing and shooting, through increasing auto-delegating of many functions to smarter and smarter cameras. But, what we basically gain by this process is speed. It certainly takes much less time to shoot and get an acceptable result as the years roll by. “Well”, you may well ask, “doesn’t that mean the whole process is also easier?”

Tricky question, as it turns out.

In that you can take technically better images with less effort the further we roll along, then yes, it’s “easier”. But the same speed which is part of the “easy” process also means that we spend less time planning a picture, seeing it in our minds and creating it with deliberate action…cause, you know, the camera will do it. This means that it’s also easy to miss things, to fail to visualize the best way to take a shot versus the most expedient way. Slowing down by adding steps into the creation of a photograph means taking back control, so it is, if you will, “harder”, but, with practice of the total process of photographing, the ease, and even the speed all comes back anyway.

I wanted the name of this blog to contain a subtitle about journeying from taking to making images because that is the trek that most photographers eventually set out on. We begin to wonder what it would be like to be more completely in charge of what kind of pictures we wind up with, even if it’s only to take a series of baby steps. It does take more time to take the process into your own hands. But it’s not that hard. Auto-settings save you time, but they may not save your shot. Choosing the inconvenient isn’t ignoring technology. It’s making it work your will with your pictures.

THE FLOATING 50

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU CANNOT BECOME A GREAT PHOTOGRAPHER WITHOUT BEING YOUR OWN BEST EDITOR, no matter how brilliant or instinctual your shooter’s eye may be. Art is both addition and subtraction, and the image frame is about both inclusion and exclusion. You get your viewers’ attention by knowing what to show. You hold that attention, and burn your images into their minds, by learning what to pare away.

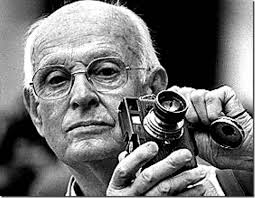

I’ve written several variations on this theme, so the best way to restate it is in the voice of the truly visionary godfather of street photography, Henri Cartier-Bresson. Ironically, this master of in-camera composition (he is reputed never to have cropped a single shot after it was taken) was nonetheless remarkably aware of what most of us must do to improve an image through post-editing:

This recognition, in real life, of a rhythm of surfaces, lines, and values is for me the essence of photography; composition should be a constant of preoccupation, being a simultaneous coalition – an organic coordination of visual elements. We must avoid snapping away, shooting quickly and without thought, overloading ourselves with unnecessary images that clutter our memory and diminish the clarity of the whole.

Insert whatever is French for “Amen” here.

I often find that up to 50% of some of my original shots can later be excised without doing any harm to the core of the photograph, and that, in many cases, actually improving them. Does that mean that my original concept was wrong? Not so much, although there are times when that’s absolutely true. The daunting thing is that the 50% floats around. Sometimes you need to cut the fat in the edges: other times the dead center of the shot is flabby. Sometimes the 50 is aggregate, with 25% trimmed from two different areas of the overall composition.

On occasion, as with the above picture (see the original off to the left), the entire bottom half of the shot drags down the top. In the cropped shot, the long lateral line between indoors and outdoors is much more unbroken, making for a more “readable” shot from left to right. The disappearance of the dark furniture at the bottom of the master shot creates no problems, and actually solves a few. Do a disciplined search of the nobler near-misses in your own work and see how many floating 50’s you discover. Freeing your shots of the things that “clutter our memory and diminish the clarity of the whole” is humbling, but it’s also a revelation.

NAIL YOUR FOOT TO THE FLOOR

I shot this on a day when I was forcing myself to master a manual f/2.8 lens wide open, and thus shoot all day in only that aperture. That made depth-of-field tricky.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY PLACES YOU IN PLENTY OF SITUATIONS WHERE YOU ARE, TO SOME DEGREE, OUT OF CONTROL. From light conditions to the technical limits of your gear to erratic weather, we have all experienced that sinking feeling that accompanies the realization that, to a great extent, we are not in the driver’s seat. Gotta wait til the sun’s up. Gotta wait for the flash to recycle. Gotta cool my heels til these people get out of the frame. Gotta getta bigger bottle of Tums.

So why, given the frequent cases in which we naturally run off the rails, would I recommend that you deliberately hobble yourself, in effect putting barriers in your own way when shooting images? Because, quite simply, failure is a better teacher than success, and you never forget the lessons gained by having to work around a disadvantage. Not only am I encouraging you to flirt with failure, I’m suggesting that there are even perfect days on which to do it…that is, the many days when there is “nothing to shoot”.

It’s really practical, when you think of it. Go out shooting on a day when the subject matter is boring, a day on which you could hardly be expected to bring back a great picture. Then nail your foot to the floor in some way, and bring back a great picture anyway. Pick an aperture and shoot everything with it, without fail (as in the picture at left). Select a shutter speed and make it work for you in every kind of light. Act as if you only have one lens and make every shot for a day with that one hunk of glass. Confine your snaps to the use of a feature or effect you don’t use or understand. Compose every shot from the same distance. The exercise matters less than the discipline. Don’t give yourself a break. Don’t cheat.

In short, shoot stuff you hate and make pictures that don’t matter, except in one respect: you utilized all of your ingenuity in making them. This redeems days that would otherwise be lost, since your shoot-or-die practice sessions make you readier when the shots really do count.

It’s not a lot different from when you were a newbie a primitive camera on which all the settings were fixed and you had zero input beyond framing and clicking. With “doesn’t matter” shooting, you’re just providing the strictures yourself, and maneuvering around all the shortcomings you’ve created. You are, in fact, involving yourself deeper in the creative process. And that’s great. Because someday there will be something to shoot, and when there is, a greater number of your blown photos are already behind you.

DISTINCTION WITHOUT A DIFFERENCE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY IS ONLY PARTLY ABOUT A STRING OF TECHNICAL DEVELOPMENTS AND BREAKTHROUGHS. It is also the chronicle of what those advances have done to democratize the art, moving it from the domain of rich tinkerers and elites to an arena in which nearly anyone can participate and compete. From the first box camera to Instagram, it is about breaking down barriers. This is not something that is open to debate. It just is.

That’s why it’s time to re-think the words professional and amateur as they apply to the making of images. This is the kind of topic where everybody tends to throw down passionately on one side or the other, with few straddlers or fence-sitters.

Those shooters whose toil is literally their bread and butter are, understandably, a little resentful of the newbie whose low-fi snap of a trending topic tops a million likes on Twitter, all without said snapper’s having mastered the technical ten commandments of exposure or composition. And those whose work is honest, earnest and sincere, yet formally uncertified, hate being thought of as less Authentic, Genuine, or Real simply because no one has printed their output in the approved channels of accepted craft, be it magazines like Nat Geo or the cover of the New York Times.

Okay, I get it. From your personal perspective, you don’t get no respect. But you know what? Get over yourself.

Do we really need to trot out the names of those who never got paid a penny for their work, mostly because their entire output consisted of inane selfies or dramatic lo-fi still lifes of their latest latte? Is it helpful to point out the people within the “official” photographic brotherhood whose work is lazy or derivative? Nope. It is beyond pointless for the two sides to get into an endless loop of So’s Your Mom.

So let’s go another way.

The words professional and amateur are, increasingly, distinctions without difference, at least as ways to attest to the quality of the end product: the photograph. When you pick up a magazine featuring a compelling image, do you ever, ever ask yourself whether it was taken by someone who got paid for it, or do you, in fact, either react to it or ignore it based on its power, its emotional impact, the curiosity and daring of the shooter? The fact is, photography has, from day one, been moved forward by both hobbyist and expert, and, in today’s world, the only thing that makes a shot “professional” is the talent and passion with which it’s been rendered. Anything else is just jaw music.

IF HUE GO AWAY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT SEEMS UNGRACIOUS FOR A PHOTOGRAPHER TO COMPLAIN ABOUT AN OVER-ABUNDANCE OF LIGHT, since that’s basically the currency we trade in. More typically we gripe about not being able to bring enough of the stuff into a shot. I mean, the entire history of the medium is one big let-there-be-more-light prayer. But that’s not to say that light can’t create annoyance when you’re in a place where there is glorious, radiant illumination of….acres of nothing.

I’m not talking about sunlight on endless expanses of starched plain. I refer here to subject matter that is so uninteresting that, even though a bumptious bounty of light is drenching everything in sight, there is nothing to make a photograph of. Nothing that compels, inspires, jars or even registers. I recently made my annual return to a festival that, due to my frequent farming of it over the years, has now bottomed out visually. There is nothing left to say about it, although all that “nothing” is stunningly lit at this time of year.

In fact, it’s only by shooting just abstracted shapes, shades and rays, rather than recognizable subjects, that I was able to create any composition even worth staying awake for, and then only by using extremely sharp contrast and eliminating color completely. To me, the only thing more pointless than lousy subject matter is beautiful looking lousy subject matter, saturated in golden hues, but signifying nothing. Kinda the George Hamilton of photos.

So the plan became, simply, to turn my back on the bright balloons, food booths, passing parade of people and spring scenery that, in earlier years, I would have been happy to capture, and instead render arrangements without any narrative meaning, just whatever impact could be seen using light as nearly the lone element. In the above picture, I did relent in keeping the silhouetted couple in the final picture, so that it’s not as “cold” as originally conceived, but otherwise it’s a pretty stark image. Photography without light is impossible, but we also have to refuse to take light “as is” from time to time, to do our best to orchestrate it, much as we would vary shadings with pencil or crayon. We know that the camera loves light, but it’s still our job to tell it where, and how, to look.

SQUARE STORIES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

BETTER PHOTO HISTORIANS THAN ME WOULD BE ABLE to pinpoint the precise moment in time when the landscape-sized image first eclipsed the square image for most photo shooters. I’d tackle the search myself, but it’s late, and I’m about a martini and a half too far into relax mode, so there it is. But, regardless of the exact instant it first began to wane, the square is back, and bigger than ever, its refreshed use as a distinct mode of composition greeted like a revelation, rather than a return. Cool beans.

The unilateral quadrangle (I get wordy when I drink) managed to barely survive on the periphery of photography, even as the square-centric Polaroid print nearly wobbled out of existence, then came back, as hipsters in the lo-fi movement revived the use of instant print cameras. Then cel phones began offering a pre-selectable square setting for their cameras, and that became a thing. But the biggest boost for the square’s comeback came with a thing called Instagram. You may have heard about this quaint little app. I understand the developers made a few bucks on it.

Still, we are pretty universally conditioned to envision pictures in either “landscape” or (flip this up on its side) “portrait” modes, so much so that director Wes Anderson garnered as much press for his use of the old anamorphic aspect ratio in The Grand Budapest Hotel as he did for the movie’s content. Strangely, the square-format photograph is, upon its return, a bit of a retro novelty.

Composing a shot in roughly 1/3 less space than a landscape frame is a challenge, simply because we have fallen out of the habit for a few decades, but it does have a certain elegance. Lately, I have tried to use the square to effectively tell stories that I traditionally saw in vast or wide scenarios. Construction projects are one such case, in that they seem to call for wide angles and far reaching vistas, what we might call scope. The above image is my attempt to express most of what goes into a building project in what some would call cramped quarters. The main story elements, that is, the action, the range of tone, the compositional depth, are all present, but confined within the quadrangle. Of course, with a DSLR, I can’t start with a square, but I can envision where in the shot the best square is, and crop to it in post-processing.

Composing for a given dimension is a discipline, and, as such, it is valuable as a practice tool, since photographers should always be visualizing every possible way to get their story told. The square may be a prison. But it also may be an answer. The end result is what matters most.

(DON’T) WATCH THIS SPACE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CALL IT “EYE-HERDING”, if you will, the art of channeling the viewer’s attention to specific parts of the photographic frame. It’s the first thing we learn about composition, and we address it with a variety of techniques, from depth-of-field to color manipulation to one of my favorites, the prioritizing of light. Light values in any image do have a hierarchy, from loud to soft, prominent to subordinate. Very few photos with uniform tone across the frame achieve maximum impact. You need to orchestrate and capitalize on contrast, telling your viewers, in effect, don’t watch this space. Watch this other space instead.

In many cases, the best natural ebb and flow of light will be there already, in which case you simply go click, thank the photo gods, and head home for a cold one. In fact, it may be that “ready to eat” quality that lured you to stop and shoot the thing in the first place. In many other cases, you must take the light values you have and make the case for your picture by tweaking them about a bit.

I have written before of the Hollywood fakery known as “day for night”, in which cinematographers played around with either exposure or processing on shots made in daylight to simulate night…a budgetary shortcut which is still used today. It can be done fairly easily with still images as well with a variety of approaches, and sometimes it can help you accentuate a light value that adds better balance to your shots.

The image at the top of this page was made in late afternoon, with pretty full sun hitting nearly everything in the frame. There was some slightly darker tone to the walls in the street, but nothing as deep as you see here. Thing is, I wanted a sunset “feel” without actually waiting around for sunset, so I deepened the overall color and simulated a lower exposure. As a result, the sky, cliffs and dogwood trees at the far end of the shot got an extra richness, and the shop walls receded into deeper values, thus calling extra attention to the “opening” at the horizon line. The shot also benefits from a strong front-to-back diagonal leading line. I liked the original shot, but with just a small change, I was asking the viewer to look here a little more effectively.

Light is a compositional element no less important than what it illuminates. Change light and you change where people’s eyes enter the picture, as well as where they eventually land.

MORE THAN FOOD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU COULD ARGUE ALL DAY ABOUT WHETHER PUBLIC SPACES POSSESS MORE VISUAL POTENTIAL when they are full or when they are dead empty, and, depending on your photographic approach, both arguments would be correct. In other words, instead of a hard-and-fast truth, you have multiple truths, depending on which space is shot by which photographer under such-and-such circumstances. Hey, if ya want a vague premise, I’m your boy.

Plazas, train platforms, museums, places of worship, restaurants, sports arenas…..all the places where people convene in big mobs have all produced stunning images taken when said places contain no people at all. After hours, before opening, last call, snow days…there are endless reasons why people don’t go to places, and the unfilled space created by their absence is a separate kind of compositional challenge.

I have stated in previous posts on this forum that, for me, museums are tremendous sources of negative space, and yet positive possibilities,when devoid of crowds. Maybe it’s when people are about to be somewhere, when something is nearly ready to happen, that public places possess a certain, well, suspense. Whatever the phenomenon, I feel it, and will always squeeze off a few shots while the moment lasts.

Similarly, eateries are both potentially joyful and potentially lonely, and that kind of uncertainty excites me as a photographer. But you may be on the opposite side of the discussion. I can certainly understand that some would see a bunch of empty tables and chairs as depressing, unmistakably desolate. But I think it depends on the photograph, and I think it always will. There are many images of two people seated together at a cafe who are, sadly, miles apart due to their estrangement, and there are an equal number of pics of a hall just before celebrants from a wedding stream in. As with so much in photography, feeling comes both from what you did and didn’t show.

DOCUMENTARY OR DRAMA?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I RECENTLY HEARD AN INTERESTING CRITIQUE OF A DRAMATIC CONTENDER for Best Film in the 2015 Oscar race. The critic in question complained that the film in question (Boyhood) was too realistic, too inclusive of banal, everyday events, and thus devoid of the dynamics that storytellers use to create entertainment. His bottom line: give us reality, sure, but, as the Brits say, with the boring bits left out.

If you’re a photographer, this argument rings resoundingly true. Shooters regularly choose between the factual documentation of a scene and a deliberate abstraction of it for dramatic effect. We all know that, beyond the technical achievement of exposure, some things that are real are also crashingly dull. Either they are subjects that have been photographed into meaninglessness (your Eiffel Towers, your Niagara Fallses) or they possess no storytelling magic when reproduced faithfully. That’s what processing is for, and, in the hands of a reliable narrator, photographs that remix reality can become so compelling that the results transcend reality, giving it additional emotive power.

This is why colors are garish in The Wizard Of Oz, why blurred shots can convey action better than “frozen” shots, and why cropping often delivers a bigger punch and more visual focus than can be seen in busier compositions. Drama is subject matter plus the invented contexts of color, contrast, and texture. It is the reassignment of values. Most importantly, it is a booster shot for subjects whose natural values under-deliver. It is not “cheating”, it is “realizing”, and digital technology offers a photographer more choices, more avenues for interpretation than at any other time in photo history.

The photo at left was taken in a vast hotel atrium which has a lot going for it in terms of scope and sweep, but which loses some punch in its natural colors. There is also a bit too much visible detail in the shot for a really dramatic effect. Processing the color with some additional grain and grit, losing some detail in shadow, and amping the overall contrast help to boost the potential in the architecture to produce the shot you see at the top of this post. Mere documentation of some subjects can produce pretty but flaccid photos. Selectively re-prioritizing some tones and textures can create drama, and additional opportunity for engagement, in your images.

THE CENTER HOLDS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST FASCINATING PARTS OF THE LEGEND of Henri Cartier-Bresson, the artist who is the world’s model for street photography, is the oft-repeated story that he never cropped a shot over the many decades of his remarkable career. Thus the man who originated the phrase “the decisive moment” to indicate that there was but one ideal instant to capture something perfectly in the camera is also credited with creating flawless on-the-spot compositions, image after image, year after year. Yeah, well….

I love HCB, and I personally can’t find a single one of his images that I could improve upon, no matter where I was to wield my magic scissors. But just as the writer in me believes that great novels aren’t written, but re-written, I believe that many great photo compositions emerge after much additional consideration, long after the shutter snaps. It’s not that one shouldn’t strive to get things as perfect as possible in the moment. In fact, there is overwhelming evidence that many photographers do exactly that, nearly all the time.

It’s that “nearly”, however, that describes most photos, something which might be converted to “definitely” in the cropping process. In fact, I am starting to feel that the very first thing to be done with a picture in post-production is to just start paring away, only stopping when the center of the idea has been reached. It’s gut-wrenching, since we usually fall in love with our pictures at first sight (and in their first versions). But even if God decided to make one of us, say Cartier-Bresson, the messenger of his divine eye, he certainly didn’t make that trait as common as, say, green eyes or freckles. For most of us, most of the time, we need to eliminate everything that diverts the eye anywhere but where the main message is. As an example, the hammock image above is the result of cutting away nearly 2/3 of the original photograph.

There are a few times when an image comes full-born out of the camera, all muscle and no fat. However, in the digital age, re-thinking one’s realization of a concept is easier than it’s ever been, and there is no downside to doing so. If there is a narrative ground-zero to your photo, don’t worry. The center will hold.

FRAGMENTS AND SHARDS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

GLASS SURFACES REPRESENT A SERIES OF CHOICES FOR PHOTOGRAPHERS, an endless variety of effects based on the fact that they are both windows and mirrors, bouncing, amplifying or channeling light no less than any other subject in your frame. No two shooters approach the use (or avoidance) of glass as a compositional component in quite the same way. To some, it’s a barrier that they have to get past to present a clear view of their subject. To others, its fragments and shards of angle and light are part of the picture, adding their own commentary or irony.

I usually judge glass’ value in a photograph by two basic qualifiers: context and structure. First, context: suppose you are focused on something that lies just beyond a storefront window. What visual information is outside the scope of the viewer, say something over your shoulder or across the street, that might provide additional impact or context if reflected in the glass that is in direct view? It goes without saying that all reflections are not equal, so automatically factoring them into your photo may add dimension, or merely clutter things up.

The other qualifier is the structure of the glass itself. How does the glass break up, distort, or re-color light within an enclosure? In the above image, for example, I was fascinated by the complex patterns of glass in an auto showroom, especially in the way it reassigned hues once the sun began to set. I had a lot of golden light fighting for dominance with the darker colors of the lit surfaces within the building, making for a kind of cubist effect. No color was trustworthy or natural , and yet everything could be rendered “as is” and regarded by the eye as “real”. The glass was part of the composition, in this instance, and at this precise moment. Midday or morning light would render a completely different effect, perhaps an unwelcome one.

Great artists from Eugene Atget to Robert Frank have created compelling images using glass as a kind character actor in their shots. It’s an easy way to deepen the impact of your shots. Let the shards and fragments act like tiles to assemble your own mosaics.

A FORWARD STEP BACK

Skies which appear wispy in color can pick up some drama in black & white with the use of a red filter.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SOME CHOICES IN LIFE ARE BINARY, EITHER YES OR NO. The light switch is either all “on” or all “off”. Photographic choices have never been binary, since there are only a few real rules about how to achieve the image you want and more than a million reasons why those rules have to be jettisoned, because they actually stand in the way of that image.

When digital photography arrived, there was a tendency to assert that everything associated with film photography was as obsolete as a roll of Kodachrome 64. In fact, the further we proceed into the digital age, the more we realize that there are many good practices from the days of emulsions and negatives that have solid application in the age of zeroes and ones. It would be ridiculous to say categorically that every tool of one era must be abandoned in the image-making of the next. Lenses, exposure, lighting basics, and many more elements of film-based creativity have equivalents in digital. None of them are good all the time, and none of them should be ruled out without exception.

The use of filters is one such element. Many film-based photogs worth their salt have used filters as a matter of course, and, despite the amazing in-camera and post-production fixes of the present day, these little bits of accent glass still produce dazzling effects with a minimum of investment, and help shooters maintain a close, hands-on control of their images in the moment. And one of my favorites here in the American southwest, land of endless, often blistering sun, is the red 25 filter.

Used to punch up contrast and accentuate detail for black and white, the red 25 renders even the lightest skies into near blackness, throwing foreground objects into bold relief and making shadows iron sharp. On a day when fluffy clouds seem to blend too much into the sky, the red 25 makes them pop, adding additional textural detail and a near-dimensional feel to your compositions. Additionally, the filter dramatically cuts haze, adding clear, even tones to the darkened skies. Caution here: the red 25 could cost you several stops of light, so adjust your technique accordingly.

Many whose style has developed in the digital age might prefer to shoot in color, then desaturate their shots later, simulating this look purely through software, but I prefer to make my own adjustments to the scene I’m shooting while I am shooting it. I wouldn’t paint a canvas in one place and then fix my choice of colors a week later, hundreds of miles away from my dream sunset. Filters are from a world where you conceive and shoot now. The immediate feedback of digital gives you the part of that equation that was absent in film days, that is, the ability to also fix it, now. Photography can’t afford to cut itself off from its own history by declaring tools from any part of that history obsolete. A forward step, back is often the deftest dance move.

THE VANISHED NORMAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

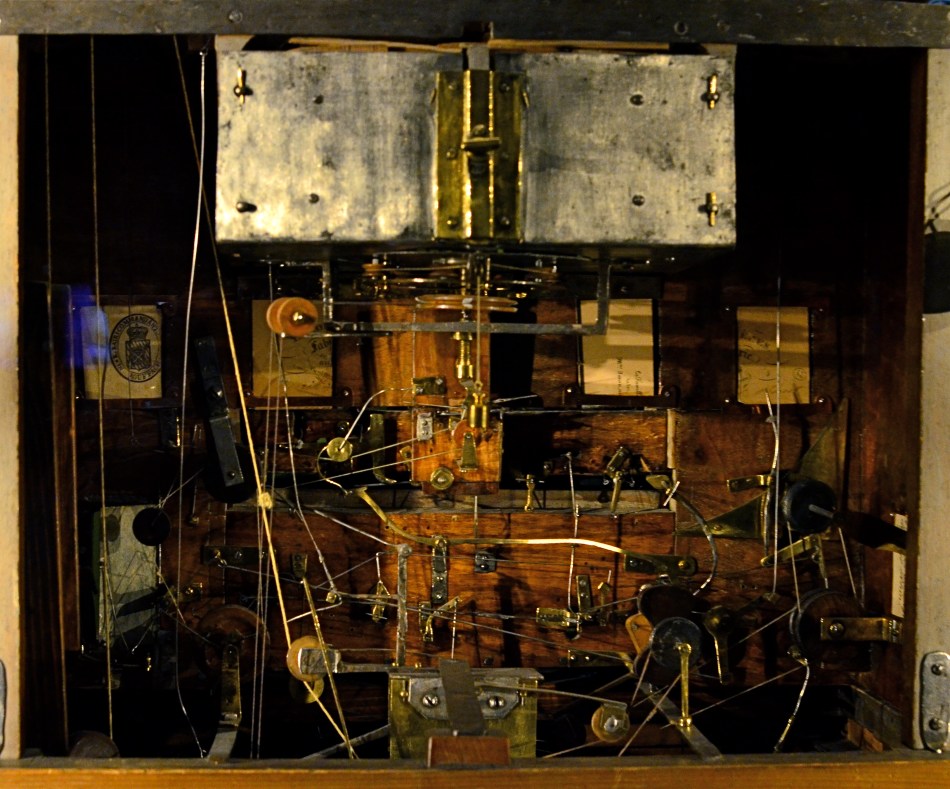

THE FUTURE DOESN’T ARRIVE ALL AT ONCE, just as the past doesn’t immediately vanish completely. In terms of technology, that means that eras kinds of smear across each other in a gradual “dissolve”. Consider the dial telephone, which persisted in various outposts for many years after the introduction of touch-tone pads, or, more specifically, Superman’s closet, the phone booth, which stubbornly overstayed its welcome long past the arrival of the cel. The “present” is always a mishmosh of things that have just arrived and things that are going away. They sort of pass each other, like workers at change of shift.

Photographically, this means that there are always relics of earlier eras that persist past their sell-by date. They provide context to life as part of a kind of ever-flowing visual history. It also means that you need to seize on these relics lest they, and their symbolic power, are lost to you forever. Everything that enjoys a brief moment as an “everyday object” will eventually recede in use to such a degree that younger generations couldn’t even visually identify it or place it in its proper time order (a toaster from 1900 today resembles a Victorian space heater more than it does a kitchen appliance).

Ironically, this is a double win for photographers. You can either shoot an object to conjure up a bygone era, or you can approach it completely without context, as a pure design element. You can produce substantial work either way.

Some of the best still life photography either denies an object its original associations or isolates it so that it is just a compositional component. The thing is to visually re-purpose things whose original purpose is no longer. Photography isn’t really about what things look like. It’s more about what you can make them look like.