MAKING THE MIRACLES MUNDANE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

GIVEN OUR USUAL HUMAN PROPENSITY FOR USING PHOTOGRAPHY AS A LITERAL RECORDING MEDIUM, most of our pictures will require no explanation. They will be “about” something. They will look like an object or a person we have learned to expect. They will not be ambiguous.

The rest, however, will be mysteries…..big, uncertain, ill-defined, maddening, miraculous mysteries. Stemming either from their conception or their execution, they may not immediately tell anyone anything. They may ring no familiar bells. They may fail to resemble most of what has gone before. These shots are both our successes and failures, since they present a struggle for both our audiences and for ourselves. We desperately want to be understood, and so it follows that we also want our brainchildren to be understood as well. Understood…and embraced.

It cannot always be, and it should not always be.

No amount of explanatory captioning, “backstory” or rationalization can make clear what our images don’t. It sounds very ooky-spooky and pyramid- power to say it, but, chances are, if a picture worked for you, it will also work for someone else. Art is not science, and we can’t just replicate a set of coordinates and techniques and get a uniform result.

There is risk in making something wonderful….the risk of not managing to hit your mark. It isn’t fatal and it should not be feared. Artistic failure is the easiest of all failures to survive, albeit a painful kick in the ego. I’m not saying that there should never be captions or contextual remarks attached to any image. I’m saying that all the verbal gymnastics and alibis in the world won’t make a space ship out of a train wreck.

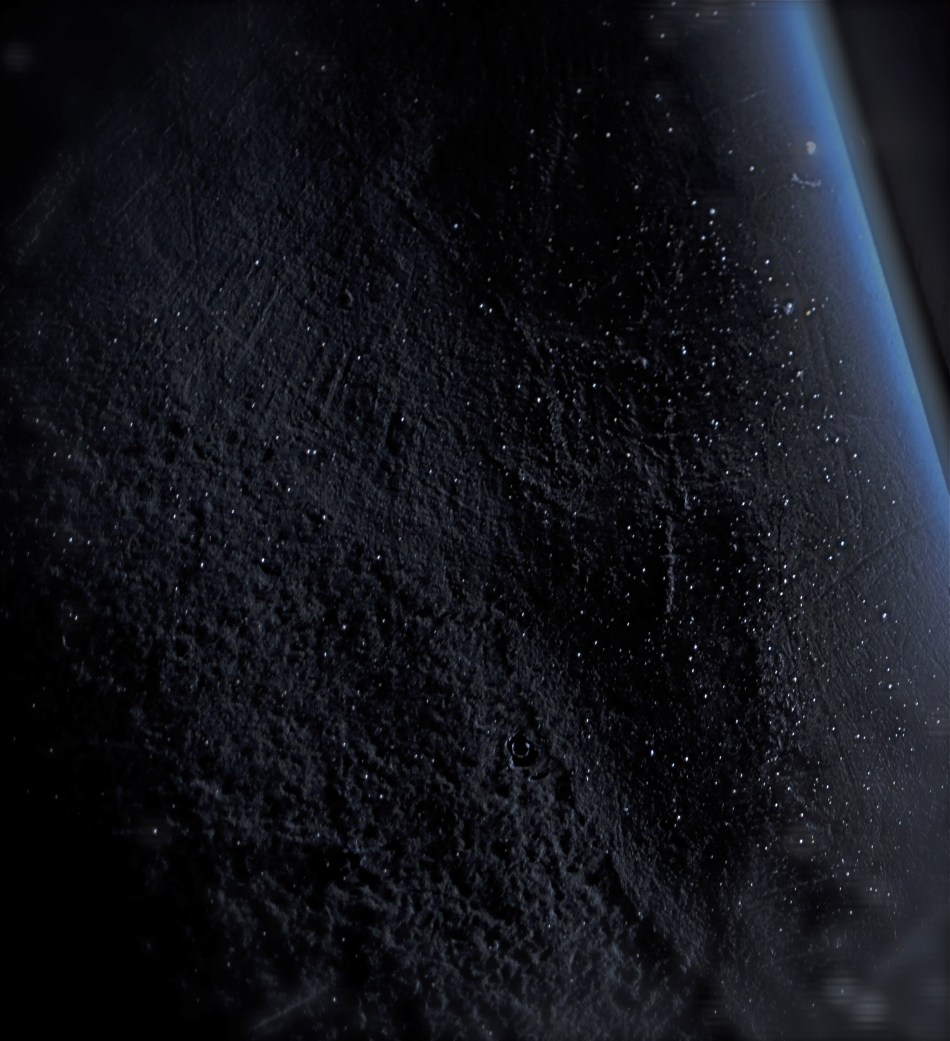

The above image is an example. If this picture does anything for you at all, believe me, my explanation of how it was created will not, repeat, not enhance your enjoyment of it one particle. Conversely, if what I tried is a swing and a miss, in your estimation, I will not be able to spin you a big enough tale to see magic where there is none. I like what I attempted in this picture, and I am surprisingly fond of what it almost became along the way. That said, I am perfectly fine with you shrugging your shoulders and moving on to the next item on the program.

Everything is not for everybody. So when someone sniffs around one of your photographs and asks (brace for it), “What’s that supposed to be?”, just smile.

And keep taking pictures.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

Related articles

- Weakness as Potential Strength (munchow.wordpress.com)

- Hidden Surprises in the Mundane (piconomy.wordpress.com)

NOT A LEG TO STAND ON

No tripod, no problem. Minimal noise even at 3200 ISO. Handheld in NYC’s theatre district at 1/50 sec., f/3.5, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ADVANCES IN PHOTOGRAPHY, WHETHER IN THE SCIENCES OF LENSES, FILMS, SENSORS OR TECHNIQUE, ALL HAVE, AS THEIR AIM, THE SAME RESULT: to make it easier to take more pictures…more often, and with fewer barriers between what you see and what you can catch in the box. Taking more pictures means increasing the yield of wonderful pictures, even if 95% of what you shoot is doody, and getting to the decisive moment of the “click” beats any other imperative. Any gimmicks or toys that don’t increase your readiness to shoot are wasteful detours.

This means that we are constantly weeding out dead growth, trimming away systems or ideas that have outgrown their usefulness. Rusty ways of doing things that cost us time, require extra steps, and eventually rob us of shots.

And that’s why it’s the age of the tripod is nearly over.

Getting past our artistic bias toward the ‘pod as a vital tool in the successful creation of images is tough; we still associate it with the “serious” photographer, even though today’s cameras solve nearly all of the problems tripods were once reliable in offsetting. What we’re left with, regarding the tripod’s real value, then, is old brain wiring and, let’s face it, sentiment.

More importantly, to my first point, the tripod is not about, “Okay, I’m ready!”. It’s about, “Hold on, I’ll be ready in a minute.” Worse yet, to the petty dictators who act as the camera police in churches, monuments, retail establishments and museums, they scream, “you can’t be here”. Call me crazy, but I still think of lack of access (spelled “getting kicked out”) as, well, sort of a hindrance to photography.

Just sayin’.

Tripods were, once upon a time, wonderful protection again several key problems, among them: slow film/sensor speed, vibration risk, and sharpness at wider apertures, all of which have long since been solved. Moreover, tripods may tempt people to shoot at smaller apertures, which could lead to softer overall images.

Had I stopped to set up a tripod here, my light, and my chance, would have melted away. 1/15 sec,. handheld, with a 35mm prime, wide-open, at f/1.8, ISO 640.

I readily concede that tripods are absolutely vital for extended night exposures, light painting, miniature work, and some other very selective professional settings. But for more than a century, ‘pods have mostly been used to compensate where our cameras were either flawed or limited. So, if those limits and flaws have faded sufficiently to allow you to take a nighttime snap, handheld at f/1.8, with a 1/15 shutter speed and the virtual guarantee of a well-lit shot, with negligible noise, why would you carry around twice the gear, pretty much ensuring that you would lose time, flexibility, and opportunities as a result?

The tripod has served us well, as was once true of flash powder, glass plates, even the torturous neck braces used to hold people’s heads in position during long exposures. But it no longer has a leg to stand on.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

TAKING / BRINGING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

INTELLECTUALLY, I KNOW THAT PHOTOGRAPHS DON’T NECESSARILY HAVE TO BE “ABOUT”, well, anything, but that doesn’t stop the 12-year-old photo newbie deep inside me from trying to produce images with “meaning” (yawn). Some reason to look. A subject. A story line. A deliberate arrangement of things for the purpose of communicating…something. Itchy and twitchy within my artist’s skin as I always am, I am never more out of my element than when I make a picture that is pure composition and form, a picture that has no reason to exist except that I wish it to.

As I get older, I get looser (no G.I. tract jokes about the elderly, please), and thus making what you might call “absolute” images gets easier. I just had to learn to give myself permission to do them. Unlike Atget, Brassai, and half a dozen early pioneering photographers, I don’t have to take pictures to earn my bread, so, if I capture something that no one else “gets” or likes, my children will not starve. Still, the act of making photographs that carry no narrative is far from native to me, and, if I live to be 125, I’ll probably learn to relax and really do something okay by about 93.

The process can be a head-scratcher.

The above image is an “absolute” of sorts, since I have no emotional investment whatever in the subject matter, and have nothing to reveal about it to anyone else. The arbitrary and somewhat sterile symmetry of this room, discovered during a random walk through a furniture store, just struck me, and I still cannot say why. Nor can I explain why it scores more views on Flickr over some of my more emotional work by a margin of roughly 500 to 1. A whole lot of people are seeing something in this frame, but I suspect that they are all experiencing something different. They each are likely taking vastly varied things from it, and maybe they are bringing something to it as well. Who knows what it is? Sense memory, a fondness for form or tone, maybe even a mystery that is vaguely posed and totally unresolved.

“Even though there are recognizable objects making up the arrangement, the result is completely abstract.There isn’t a “human” story to tell here, since this room has never been inhabited by humans, except for wandering browsers. It has no history; nothing wonderful or dreadful ever happened here. In fact, nothing of any kind ever happened here. It has to be form for its own sake; it has no context.

I liked what happened with the very huge amount of soft window light (just out of frame), and I thought it was best to render the room’s already muted tones in monochrome (it wasn’t a big leap). Other than that, it would be stupid to caption or explain anything within it. It is for bringers and takers, bless them, to confer meaning on it, if they can. As I said earlier, it’s always a little scary for me to let go of my overbrain when making a picture.

Then I remember this is supposed to be about feeling as well as thinking.

***Deep breath***

Next.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

Related articles

- First Critique (cohensrphotography.wordpress.com)

HOLLYWOOD NIGHTS

Moonlight night around the poolside, only not really: a “day-for-night” shot taken at 5:17pm. 1/400 sec., f/18, ISO 100, 35mm, using a tungsten white balance.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

TIME LIMITS US IN EVERY PHOTOGRAPHIC SITUATION: LIGHT HEMS US IN EVEN FURTHER. Of course, the history of photography is rife with people who refuse to just accept what time and nature feel like giving them. In fact, that refusal to settle is source of all the artistry. Too bright? Too bland? Wrong time of day? Hey, there’s an app for that. Or, more precisely, a work-around. Recently, I re-acquainted myself with one of the easiest, oldest, and more satisfying of these “cheats”, a solid, simple way to enhance the mood of any exterior image.

And to bend time… a little.

Same scene as above taken just seconds later, but with normal white balancing and settings of 1/250 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

It’s based on one of Hollywood’s long-standing budget-savers, a technique called day-for-night. For nearly a century, cinematographers have simulated nightfall while shooting in the daytime, simply by manipulating exposure or processing. Many of the movie sequences you see represented as “night” are, in fact, better lit than any “normal” night, unless you’re under a bright, full moon. Day-for-night allows objects to be more discernible than in “real” night because their illumination is actually coming from sunlight, albeit sunlight that’s been processed differently. Shadows are starker and it’s easier to highlight what you want to call attention to. It’s also a romantically warm blue instead of, well, black. It’s not a replication of reality. Like most cinematic effects, it’s a little bit better than real.

If you’re forced to approach your subject hours before sunset, or if you simply want to go for a different “feel” on a shot, this is a great shortcut. Even better, in the digital era, it’s embarrassingly easy to achieve: simple dial up a white balance that you’d normally use indoors to balance incandescent light. Use the popular “light bulb” icon or a tungsten setting. Indoors this actually helps compensate for cold, bluish tones, but, outside, it amps up the blue to a beautiful, warm degree, especially for the sky. Colors like reds and yellows remain, but under an azure hue.

The only other thing to play with is exposure. Shutter-speed wise, head for the high country

at anywhere from f/18 to 22, and shorten your exposure time to at least 1/250th of a second or shorter. Here again, digital is your friend, because you can do a lot of trial and error until you get the right mix of shadow and illumination. Hey, you’re Mickey Mouse with the wizard hat on here. Get the look you want. And don’t worry about it being “real”. You checked that coat at the door already, remember?

Added treats: you stay anchored at 100 ISO, so no noise. And, once you get your shot, the magic is almost completely in-camera. Little or no post-tweaking to do. What’s not to like?

I’m not saying that you’ll get a Pulitzer-winning, faux-night shot of the Eiffel Tower, but, if your tour bus is only giving you a quick hop-off to snap said tower at 2 in the afternoon, it might give you a fantasy look that makes up in mood what it lacks in truth.

It ain’t the entire quiver, just one more arrow.

Follow Michael Perkins at Twitter @MPnormaleye.

NOTHING IS REVEALED

Julia Margaret Cameron, 19th-century self-portrait pioneer, currently on exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum Of Art.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE TITLE OF THIS POST IS ONE OF MY FAVORITE LINES IN ALL OF BOB DYLAN’S PRODIGIOUS OUTPUT, coming from The Ballad Of Frankie Lee And Judas Priest, on the John Wesley Harding album. I often pop the phrase into casual conversations where it’s clear that more heat, rather than light, has been generated. Nothing to see here, folks. No new ground has been broken. No fresh truth has been unearthed.

Nothing is revealed.

This phrase came back to me a while back when looking at the raw statistics for Instagram, which indicates that, currently, over 90,000,000 images on the foto-share service currently bear the hashtag “#me”. Call them selfies, call them an epidemic of narcissism, call them banal.

But don’t, for the love of God, call them portraits.

How has it come to this? How can merely pointing a phone camera back at your own punim, and saturating it with distortion and over-amped flash, pass for a telling testament to who you are, what you dream, what you represent in the world?

Of course, the tselfie tsunami does none of these things. It actually puts distance, if not actual barriers, between your real self and the world, by creating some lifeless avatar to ward off true discovery of yourself by, well, anyone. By comparison, even the four-for-a-quarter snaps of antique photo booths are searing documents of truth.

Photography’s evolution is illuminated by the great masters who stepped in front of their own cameras

to try to give testimony, recording innovative, penetrating evidence of who they were. Currently, a show featuring one of the medium’s greatest pioneers in this area, Julia Margaret Cameron, is packing them in at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, and with good reason. Cameron’s attempts to capture herself in not only natural but fantastic settings led the way for interpretive portraitists from Richard Avedon to Annie Liebowitz. Along the way, she learned what to look for, and immortalize, in the faces of others, including Alfred Lord Tennyson, Charles Darwin, Robert Browning, and other bright lights of the 19th century.

Oddly, none of her work was done by crooking her arm 90 degrees back toward her booze-flushed face at a kegger and saying “cheese.”

I’ve written before, in these pages, of the real value of self-portraits as a teaching tool and experimental lab for photographic technique. By contrast, “Selfies” are false faces created to keep the world away, not invite it in. And they remind us, courtesy of Bobby D., of the three worse words of insult that can ever be aimed at any photograph, anywhere:

Nothing is revealed.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

Related articles

- Portraits by Julia Margaret Cameron, One of Photography’s Early Masters, on Display at the Met (muirhousepubs.wordpress.com)

- Julia Margaret Cameron: Pioneer of Modern Glamour Photography? (bigthink.com)

LEAVE THEM WANTING MORE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PAINTERS INSTINCTIVELY KNOW WHEN IT’S TIME TO REVEAL, AND WHEN IT’S BEST TO CONCEAL. Dark passages or hidden detail within a painting are accepted as part of the storytelling process. That is, what you don’t see can be as valuable a visual element as what you’ve chosen to show. By contrast, many photographers seem to come to this conclusion late , if ever. That is, we’re a little twitchy at not being able to illuminate every corner of our frame, to accurately report all the detail we see.

We try to show everything, and, in so doing, we defeat mystery, denying the viewer his own investigative journey. We insist on making everything obvious. Unlike painters, we don’t trust the darkness. We never “leave them wanting more”.

Fortunately, fate occasionally forces our hand.

The image at the top of this post started out as an attempt to capture the activity of an entire family that was walking their dog near a break in the dense trees that line the creek at Red Rocks Crossing in Sedona, Arizona. The contrast between the truly dark walking paths beneath the trees and the hyper-lit creek and surrounding hardpan is like night and day. The red rocks and anything near them, especially in the noonday sun, reflect back an intense amount of glare, so if your shots are going to include both shady foliage and sunlit areas, you’re going to have to expose for either one or the other. You might be able to get a wider range of tones by bracketing exposures to be combined later in post-processing, but for a handheld shot of moving people, your choices are limited.

I was trying to come to terms with this “either/or” decision when nearly everyone in the family moved away from the creek and into the dense foliage, leaving only one small boy idling at creekside. Feeling my chance of capturing anything draining away, I exposed for the creek, rendering the boy as a silhouette just as he made a break into the woods to rejoin his family. No chance to show detail in his face or figure: he would just be a dark shape against a backdrop of color. The decision to “make things more complicated” had already been taken away from me.

I had what I had.

Turns out that I could not have said “little boy” any better with twice the options. The picture says what it needs to say and does so quietly. No need to over-explain or over-decorate the thing. Darkness had asserted itself as part of the image, and did a better storytelling job all by itself.

I had much more time to calculate many other shots that day, but few of my “plans” panned out as well as the image where I relinquished control completely.

Hmmm….

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter #MPnormaleye

Related articles

- Red Rock Love (missfunshine.wordpress.com)

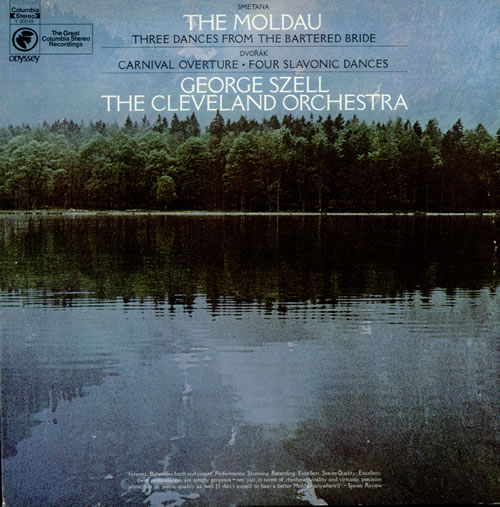

THE BOOK OF KODAK

The Long-Distance Runner: The Most Successful Photography Instruction Series In History, Eastman Kodak’s How To Make Good Pictures (28th Edition,1943-47). From the collection of the author.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

KODAK’S SAD AND WOBBLY RE-EMERGENCE FROM BANKRUPTCY, announced this week, finalizes the process of “saving” a famous name, while annihilating the legacy of innovation that made that name great for over a century. Having already said goodbye to Kodachrome, most of its other trademark films, and camera production itself, Kodak will now concentrate on “imaging products”, which, for, most of us, means “printers”. Most of the news coverage of this corporate resurrection will “focus” (sorry) on what the new company stock will be worth, who goes, who stays, and a few scant mentions of the company’s original role as camera producer to the world.

That will leave a significant part of the story untold.

Certainly, George Eastman’s genius for marketing helped develop the first flexible roll films, then ingeniously created a market for them by putting a basic, usable camera in the hands of the Everyman. Nearly everyone has heard the slogan Kodak created to demonstrate how truly effortless its products had made photography: you press the button and we do the rest. But none of that would have guaranteed the company’s growth if Kodak has not also decided to become photography’s first great mass teacher, creating pro-active education programs to guarantee that, not only could Uncle Clem snap a photo easily, he could snap a good photo easily. What had once been a dark art for a select cabal of techno-wizards became, under Kodak’s outreach, something that could anybody could do.

And Kodak was going to show you how to do it.

There was a time when this Kodak Vest-Pocket Hawkeye was truly intimidating. How To Make Good Pictures made it your friend.

Beginning before the end of the Victorian era, the company began to publish the first of an endless stream of practical guides on technique and simple theory aimed at the average shutterbug. Starting in 1898 with Picture Taking And Picture Making (115 pages of tips in a cardboard cover for fifty cents!), Eastman Kodak moved to 1905’s The Modern Way In Picture Making, and, finally, to the most successful photo instruction series in history, How To Make Good Pictures, introduced in 1912 and revised continually until finishing up with its 37th edition, in 1995. Over the years the “make” in the title had been changed to “take”, and its 1890’s essays on bromide paper, collodion matte, and ground-glass focusing had evolved, over the decades, to instructions on the use of flash, color, drop-in film cartridges, and “how to tell a picture story” with your Kodacolor slides. Hundreds of printings and millions of sales later, How To Make Good Pictures forged an ironclad link between consumer and company in a way no corporation before or since has done.

To everything there is a season. Kodak’s (now historically) tragic failure to see digital photography as a viable consumer revolution, until it was too late, is a matter of raw record. The company that taught the world to see had a blind spot, a fatal one, and the irony that nearly all of the rest of the industry developed digital technology by applying processes originated (and patented) by Kodak makes the story even sadder.

But, once upon a time, the Eastman Kodak Company not only knew what the future of photography was going to look like, it wrote a handy dandy little book that told everyone how to master that future.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye

Related articles

- Kodak moments are just a memory as company exits bankruptcy (kansascity.com)

THREE STRIKES AND YOU’RE…IN?

“Wreck Of The Old ’87”. Wreck is right. 1/80 sec., variable depth of field created with a Lensbaby attachment, ISO jacked to 640, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN SORTING MY IMAGES INTO KEEPERS AND CLUNKERS, I ALWAYS SUFFER THE SAME BIAS. Whereas some people might be too eager to find reasons why a picture should be inducted into the former group, I nearly always search for reasons to toss them into the latter one. I always know right away what I’ve failed to achieve in a given frame, and its flaws glow like safety orange in my brain to the point where I not only can’t credit myself for the photo’s stronger elements, I can no longer even see them. I therefore consign many pictures to the rubbish heap, a few of them prematurely.

Usually, however my first call is the right one. I very seldom revisit a picture I initially disliked and find something to redeem it. So it was kind of headline news when I recently “saved” a photo I had originally (and wisely) savaged. Hell, I’m still ambivalent, at best, about it, but I can’t truly classify it as an outright Lost Child anymore.

It came from a random day of practice I had undertaken with a Lensbaby, one of those effects lenses designed to give you the ability to manually throw parts of your image out of sharp focus, in fact to rotate around and create various “sweet spots” of sharpness wherever you want to. I don’t use the thing a lot, since it seems, on some level, damned silly to put defects into your pictures on purpose just to convince yourself you are, ahem, an artiste. But, all work and no play, etc. etc., so I was clicking away inside a dimly lit building at a railway museum in which a huge layout of miniature train dioramas is a regular attraction. I seemed to be going out of my way to create a picture that would normally be “three strikes and you’re out”…..that is:

poorly lit, and loving it

poorly focused, otherwise known as, sure, I meant to do that, and

a half-baked attempt to make something fake appear real.

Only one of the shots sparked my interest at all, purely because it seemed to contain a sort of… mystery. So many dark corners. So many unexplained details. A very disorienting, dreamlike quality that had to have jumped into the camera without any help from me. It looked both hyper-real and utterly false, simultaneously fearsome and fascinating. Again, this all happened in spite of, not because of, any action on my part. I added no post-processing to the shot, except to desaturate it and slather on a layer of sepia. Other than that, I left it in its original sloppy, random state.

And then I decided it was still junk and forgot about it for a few months.

Just why I have, in recent days, tried to rehabilitate my thinking about it is anyone’s guess. Like I sad at the top, I look for reasons to reject my work, not excuse it. This has little to do with modesty. It’s just an admission that control is so much a part of my make-up that I recoil from images where I seem to have absolutely relinquished that control. They scare me a little.

But they thrill me a little too. And, as Vonnegut says, so it goes.

Perhaps the best thing is to maintain the Keepers and Clunkers piles, but add a third, labeled “Not Really Sure”.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

Related articles

- Peering Through a Shaft of Light (johnbee.ca)

LEARNING TO LIVE WITH “THE NUMBER”

Will I have any regard for this image in five years? Ten? How about in six months? And why? 1/40 sec., f/9, ISO 100, 50mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S GUARANTEED. OVER OUR LIFETIMES, YOU AND I WILL TAKE REMARKABLE PHOTOGRAPHS.

There just won’t be a lot of them.

And that’s very good news.

Ansel Adams once remarked that “twelve significant photographs in any one year is a good crop”.

That’s right. Twelve.

Now, given the percentage of the massive Adams output that actually turned out to be flat-out amazing, the reverse math for how many “close, but no cigar” frames he shot would be staggering. And humbling. This after all, is a man who “experimented” with color for over thirty years, only to lament, near the end of his life that “I have yet to see–much less produce–a color photograph that fulfills my concepts of the objectives of art.” Bear in mind, also, that this lament is not coming from a hipster Instram-ing artsy close-ups of what he had for lunch.

What does this mean for us? It means that there is a number out there, the figure that enumerates how many flops we will have to be content with in order to get our own, small yield of golden eggs.

Learning to live with that number is the best hope have of getting closer to what we can be.

I can’t measure my work against anyone else’s, since “that way lies madness”. I can only mark how far I am along my journey by the distance between what made me smile today and the stuff I used to be able to look at without suppressing a strong gag reflex. Guess what: the same work that makes me want to gouge out my eyes with soup spoons, in the present, is often the exact same work that made my chest swell with pride, just the day before yesterday.

And that’s the way it should be. If your style is so wonderfully complete that it can’t be further improved on, then smash your camera on the street below and move on to something else that has the potential to either spank your ego or kick your creative butt. We’re not in this to get comfortable.

Ansel Adams one more time:

There is nothing worse than a sharp image of a fuzzy concept.

Yes, huzzah, what he said. Here’s to staying sharp.

And hungry.

And hard to please.

follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye and on Flickr at

SECOND SIGHT, SECOND LIFE

Pragmatically “useless” but visually rich: an obsolete flashbulb glows with window light. 1/80 sec., f/5.6, ISO 640, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A DECADE-AND-A-HALF INTO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY, we are still struggling to visually comprehend the marvels of the twentieth. As consumers, we race from innovation to innovation so amazingly fast that we scarcely apprehend the general use of the things we create, much less the underlying aesthetic of their physical forms. We are awash in the ingenuity of vanishing things, but usually don’t think about them beyond what we expect them to supply to our lives. We “see” what things do rather than seeing their essential design.

As photographers, we need not only engage the world as recorders of “reality” but as deliberate re-visualizers of the familiar. By selecting, magnifying, lighting and composing the ordinary with a fresh eye, we literally re-discover it. Second sight gives second life, especially to objects that have outlasted their original purpose. No longer needed on an everyday basis, they can be enjoyed as pure design.

And that’s exciting for anyone creating an image.

The above shot is ridiculously simple in concept. Who can’t recognize the subject, even though it has fallen out of daily use? But change the context, and it’s a discovery. Its inner snarl of silvery filaments, designed to scatter and diffuse light during a photoflash, can also refract light, break it up into component colors, imparting blue, gold, or red glows to the surrounding bulb structure. Doubling its size through use of “the poor man’s macro”, simple screw-on magnifying diopters ahead of a 35mm lens, allows its delicate inner detail to be seen in a way that its “everyday” use never did. Shooting near a window, backed by a non-reflective texture, allows simple sculpting of the indirect light: move a quarter of an inch this way or that, and you’ve dramatically altered the impact.

The object itself, due to the race of time, is now “useless”, but, for this little tabletop scene, it’s a thing made beautiful, apart from its original purpose. It has become something you can make an image from.

Talk about a “lightbulb moment”….

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

Related articles

- “A Sight Into My Photographic Mind” (Perspective) (mrphotosmash.wordpress.com)

FEWER TOYS, MORE TOOLS

This is Nikon’s “High-Key” effects mode. It’s a cheap gimmick, and you paid for it, even though (a) it is not High Key and (b) you can easily make this shot yourself. 1/30 sec., f/2.8, ISO 1250, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MANY OF THE “ENHANCEMENTS” OFFERED BY TODAY’S MAJOR PHOTO GEAR MANUFACTURERS ARE, IN FACT, OBSTACLES to learning how to take responsibility for making pictures. The automatic bells and whistles that are being engineered into today’s cameras seems to send the message: you don’t have to think too hard. Push the button and we will provide (and predict) the results.

It may be fabulous for convenience, but it’s lousy news for the experimentation and personal risk which are required for great photography to occur.

We live in a time of short cuts, of single-button solutions for every creative problem. We have modes for that. Low light, too much light, a day at the beach, a day in the snow, a closeup, a landscape? Guaranteed results at the dial-up of an automode. Hey, you’re an artist. No need to obsess about all that techno-whatsis. Your camera will determine the results. Just dial up what you want: it’s all automatic. You need hardly be there.

Does anyone really believe that anything of artistic value can evolve from machines being in charge? When’s the last time a computer created a novel of staggering impact? Who is taking the picture here…..you or your camera?

Fully automatic, aperture priority and shutter priority are all good basic tools, and wonderful work is done in all three modes as well as full manual. But there is a huge leap between these settings and the gaudy, gimmicky “effects” modes that are increasingly larding up cameras with novelty and diversion.

Let’s take a look at some of the prime offenders. Are these toys necessary?

NIGHT VISION: If you want a picture to look like you took it while on combat recon in a forward area of Afghanistan, go for this option. Boosts your ISO up to 25,600 so you can get some image on the sensor, even in utter blackness, loaded with grain and visual muck. And why? Useless.

COLOR SKETCH: Concerts your original image into an “arty” rendering, minus the shadows, attenuating tones, or subtlety. Looks just like a classy artist knocked out a masterpiece with his box of charcoals! Fools no one except perhaps extremely learning-challenged chimps. If you want to be a painter, fine, then do it, but let’s stop calling this an enhancement.

MINIATURE EFFECT. Okay, so you can’t afford a real tilt-shift lens to create the illusion that your aerial shot of Paris is really a toy-sized tabletop model, so let’s take your photo and throw selective parts of it out of focus. That should be good enough. We’ll now allow a five-minute pause here for the exactly two times you’ll ever care about making a picture like this.

SELECTIVE COLOR. De-saturate portions of your original for dramatic effect. This is the opposite of the images of a century ago, when people, before color film, added selective hues to monochrome images…for dramatic effect. Only thing is, drama should already be in the picture before you apply this gimmick, hmm? Like many effects modes, this one tempts you to use it to fix a photo that didn’t tell its story properly in the first place. And yes, I have sinned in this area, sadly.

SILHOUETTE. The camera makes sure your foreground subjects are dark and have no detail. In other words, it takes pictures exactly the way your Aunt Sadie did with her Instamatic in 1963. Oh, but it’s so artistic! Yes, cameras always make great art. All by themselves.

HIGH KEY or LOW KEY. This used to mean lightening or darkening of selected items done by meticulous lighting. Now, in Camera Toyland, it means deliberately under-or-overexposing everything in the frame. See earlier reference to your Aunt Sadie.

As far as what should be built into cameras, I’m sure that you could compose your own wish list of helpful tools that could be available as quick-dial aids. My own list would, for example, include the moving of white balance choices from the screen menus to the mode dial. Point is, for every ready-made effect that you delegate to the camera, you are further delaying the education that can only come from doing things yourself. If you want a happy picture, make one, rather than taking a middling one and then dialing up the insertion of a magical birthday cake in the middle of the shot after the fact.

As point-and-shoots are eventually replaced by smartphones and DSLRs position themselves to remain competitive as least on the high-end portion of the market, there seems to be a real opportunity for a revolution in camera design….away from toys and in favor of tools.

follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

THE WOMAN IN THE TIME MACHINE

by MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE TIMES WHEN A CAMERA’S CHIEF FUNCTION IS TO BEAR WITNESS, TO ASSERT THAT SOMETHING FANTASTIC REALLY DID EXIST IN THE WORLD. Of course, most photography is a recording function, but, awash in a sea of infinite options, it is what we choose to see and celebrate that makes an image either mundane or majestic.

And then sometimes, you just have the great good luck to wander past something wonderful. With a camera in your hand.

The New York Public Library’s main mid-town Manhattan branch is beyond magnificent, as even a casual visit will attest. However, its beauty always seems to me like just “the front of the store”, a controlled-access barrier between its visually stunning common areas and “the good stuff” lurking in untold chambers, locked vaults and invisible enclaves in the other 2/3 of the building. I expect these two worlds to be forever separate and distinct, much as I don’t expect to ever see the control room for electrical power at Disneyland. But the unseen fascinates, and recently, I was given a marvelous glimpse into the other side at the NYPL.

A recent exhibit of Mary Surratt art prints, wall-mounted along the library’s second-floor hall, was somehow failing to mesmerize me when, through a glass office window, I peeked into a space that bore no resemblance whatever to a contemporary office. The whole interior of the room seemed to hang suspended in time. It consisted of a solitary woman, her back turned to the outside world, seated at a dark, simple desk, intently poring over a volume, surrounded by dark, loamy, ceiling-to-floor glass-paneled book shelves along the side and back walls of the room. The whole scene was lit by harsh white light from a single window, illuminating only selective details of another desk nearer the window, upon which sat a bust of the head of Michelangelo’s David, an ancient framed portrait, a brass lamp . I felt like I had been thrown backwards into a dutch-lit painting from the 1800’s, a scene rich in shadows, bathed in gold and brown, a souvenir of a bygone world.

I felt a little guilty stealing a few frames, since I am usually quite respectful of people’s privacy. In fact, had the woman been aware of me, I would not have shot anything, as my mere perceived presence, however admiring, would have felt like an invasion, a disturbance. However, since she was oblivious to not only me, but, it seemed, to all of Planet Earth 2013, I almost felt like I was photographing an image that had already been frozen for me by an another photographer or painter. I increased my Nikon’s sensitivity just enough to get an image, letting the light in the room fall where it may, allowing it to either bless or neglect whatever it chose to. In short, the image didn’t need to be a faithful rendering of objects, but a dutiful recording of feeling.

How came this room, this computer-less, electricity-less relic of another age preserved in amber, so tantalizingly near to the bustle of the current day, so intact, if out of joint with time? What are those books along the walls, and how did they come to be there? Why was this woman chosen to sit at her sacred, private desk, given lone audience with these treasures? The best pictures pose more questions than they answer, and only sparingly tell us what they are “about”. This one, simply, is “about” seeing a woman in a time machine. Alice through the looking-glass.

A peek inside the rest of the store.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

Thanks to THE NORMAL EYE’s latest follower! View NAFWAL’s profile and blog at :

A BRIEF AUDIENCE WITH THE QUEEN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS ONLY ONE KIND OF PICTURE YOU WILL EVER TAKE OF A CAT, and that is the one she allows you to take. Try stealing an image from these spiritual creatures against their will, and you will reign over a bitter kingdom of blur, smear, and near misses.

It’s trickier to take photos of the ectoplasmic projections of departed relatives. But not by much.

I recently encountered this particular lady in a Brooklyn brownstone, a gorgeous building, but not one that is exactly flooded with light, even on a bright day. There are a million romantically wonderful places for darkness to hide inside such wonderful old residences, and any self-respecting feline will know how to take the concept of “stealth” down a whole other road. The cat in the above photo is, believe me, better at instant vaporization and re-manifestation than Batman at midnight in Gotham. She also has been the proud unofficial patrol animal for the place since Gawd knows when, so you can’t pull any cute little “chase-the-yarn-get-your-head-stuck-in-a-blanket” twaddle that litters far too much of YouTube.

You’re dealing with a pro here.

Her, not me.

Plus she’s from Brooklyn, so you should factor some extra ‘tude into the equation.

The only lens that gives me any luck inside this house is a f/1.8 35mm prime, since it’s ridiculously thirsty for light when wide open and lets you avoid the noticeable pixel noise that you’d get jacking up the ISO in a dark space. Thing is, at that aperture, the prime also has a razor-thin depth of field, so, as you follow the cat, you have to do a lot of trial framings of the autofocus on her face, since getting sharp detail on her entire body will be tricky to the point of nutso. And of course, if you move too far into shadow, the autofocus may not take a reading at all, and then there’s another separate complication to deal with.

The best (spelled “o-n-l-y”) solution on this particular day was to squat just inside the front foyer of the house, which receives more ambient light than any other single place in the house. For a second, I thought that her curiosity as to what I was doing would bring her into range and I could get what I needed. Yeah, well guess again. She did, in fact, approach, but got quickly bored with my activity and turned to walk away. It was only a desperate cluck of my tongue that tricked her into turning her head back around as she prepared to split. Take your stupid picture, she seemed to say, and then stop bothering me.

Hey, I ain’t proud.

My brief audience with the queen had been concluded.

I’ll just show myself out……

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

COMMANDER-IN-GRIEF

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MANY OF THOSE WHO TRAVEL TO WASHINGTON, D.C.’s VARIOUS MONUMENTS each year generally strike me as visitors, while those who throng to the memorial honoring Abraham Lincoln seem more like pilgrims. Scanning the faces of the children and adults who ascend the slow steps to the simple rectangular chamber that contains Daniel Chester French‘s statue of the 16th president, I see that this part of the trip is somehow more important to many, more fraught with a sense of moment, than the other places one may have occasion to view along the National Mall. This is, of course, simply my subjective opinion. However, it seems that this ought to be true, that, even more than Jefferson, Washington or any other single person attendant to the creation of the republic, Lincoln, and the extraordinary nature of his service, should require an extra few seconds of silent awe, and, if you’re a person of faith, maybe a prayer.

This week, one hundred and fifty years ago, the gruesome and horrific savagery of the Civil War filled three whole days with blood, blunder, sacrifice, tragedy, and finally, a glimmer of hope, as the battle of Gettysburg incised a scar across every heart in America. Lincoln’s remarks at the subsequent dedication of the battlefield placed him in the position of official pallbearer for all our sorrows, truly our Commander-In-Grief. Perhaps it’s our awareness of the weight, the loneliness, the dark desolation of that role that makes visitors to the Lincoln Memorial a little more humble, a little quieter and deeper of spirit. Moreover, for photographers, you want more of that statue than a quick snap of visiting school children. You want to get something as right as you can. You want to capture that quiet, that isolation, Lincoln’s ability to act as a national blotter of sadness. And then there is the quiet resolve, the emergence from grief, the way he led us up out of the grave and toward the re-purposing of America.

The statue is a simple object, and making something more eloquent than it is by itself is daunting.

The interior of the monument is actually lit better at night than in the daytime, when there is a sharp fall-off of light from the statue to the pillars and colored glass skylights to its right and left. You can crank up the ISO to retrieve additional detail in these darker areas, but you risk the addition of grainy noise. In turn, you can smooth out the noise later, but, in so doing, you’ll also smear away the beautiful grain in the statue itself.

In my own case, I decided to take three bracketed exposures, all f/5.6, , nice and wide at 20mm, low noise at ISO 100, with shutter speeds of 1/50, 1/100, and 1/200. In blending the three later in Photomatix’ Detail Enhancement mode, I found that the 1/200 exposure had too little information in it, so a composite of the three shots would have rendered the darkest areas as a kind of black mayonnaise, so I did the blend with only two exposures. Stone being the main materials in the subject, I could jack up the HDR intensity fairly high to accentuate textures, and, for a more uniform look across the frame, I gently nudged the color temperature toward the brown/amber end, although the statue itself is typically a gleaming white. The overall look is somewhat more subdued than “reality”, but a little warmer and quieter.

Abraham Lincoln was charged with maintaining a grim and faithful vigil at America’s bedside, in a way that no president before or since has had to do. Given events of the time, it was in no way certain that the patient would pull through. That we are here to celebrate his victory is a modern miracle, and the space his spirit occupies at the Lincoln Memorial is something photographers hunger to snatch away for their own.

What we try to capture is as elusive as a shadow, but we need to own something of it. The commander-in-grief’s legacy demands it.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

Related articles

- Other Proposed Designs for the Lincoln Memorial (ghostsofdc.org)

- Lincoln Memorial Under Construction (ghostsofdc.org)

IN THE LINE OF FIRE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS NO GREATER ART THAN THAT WHICH DEMANDS THAT THE VIEWER BECOME A PARTICIPANT, an active co-creator of a bond between creator and user. That is the ineffable power that pervades all great art; the ability to draw you into a world not your own, a world which, in an instant, becomes your own. This elusive quality moves art from mere depiction to a kind of partnership arrangement. It’s so uncommon, so rare, that, when we see an instance of it, the very nature of the effect is radiant, unforgettable.

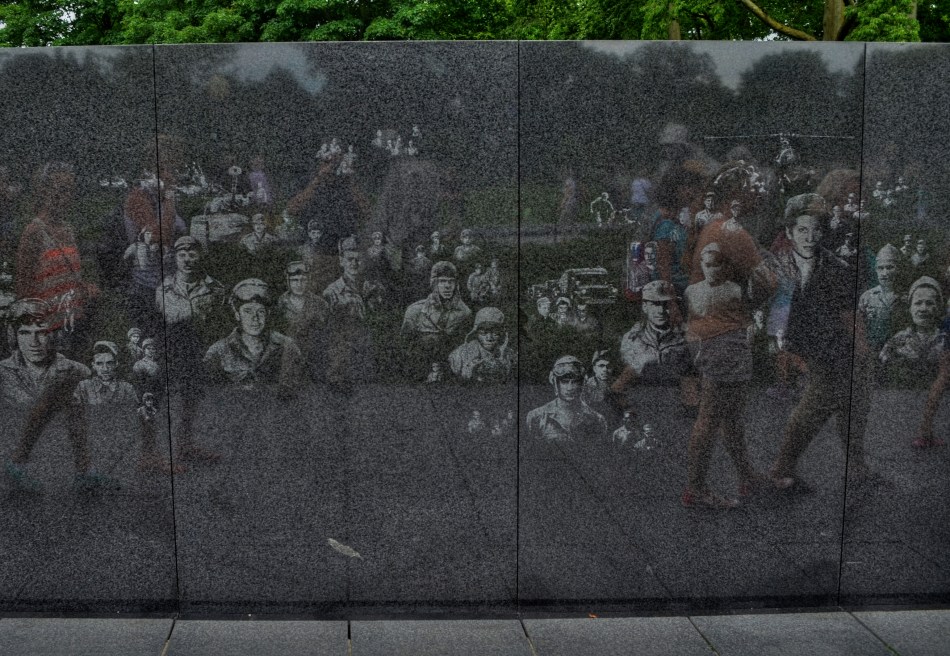

There are many attempts along Washington, D.C.‘s National Mall to name the nameless, to five utterance to the wordless qualities that define greatness, vision, loss, courage, passion, and pain. America‘s noisy, erratic journey through its young life have left trails of triumph and tragedy, paths that artists have illuminated with the various memorials and monuments which ring the mall from east to west. Some elevate presidents to the level of demigods; some mark the passage of noble laws; others, like the Vietnam War memorial, evoke deep feeling with a reverent stillness, and my favorite, the more recent Korean War Memorial, captures the quiet terror of setting out upon the grim errand of battle in a way that is eerie, and yet elegant.

Visitors to the Korean War Memorial pass a wall etched with candid photos of G.I.s who served in the conflict.

There are two major elements to the memorial, dedicated in 1995 just southeast of the Lincoln Memorial. The first is reminiscent of the wall of names that comprise the solemn Vietnam memorial, but is slightly different in that it is a wall of faces, the effigies of nameless veterans of the conflict, scanned from candid photographs and etched into a stone slab that lines one side of the site. The other, and far more haunting feature is that of a silent patrol of soldiers, its members drawn from each branch of service in the Korean conflict, setting out in a cautious recon march across an open field. The statuary figures are impressive, averaging about seven feet in height. All of the soldiers cast their nervous gaze about the area as they seem to emerge from the relative safety of a copse of trees that border the monument site. The men are exhausted, grim. There is no call to duty in their poses, no grand gestures of heroism, no “follow me, boys!” rallying cry. Sculptor Frank Gaylord has created a squad of the Spirits Of Thankless Jobs Past, laden with gear, shrouded in ponchos, their steps weary and woeful. Get close enough to them and you can almost fall into step among them. Unlike the church-like quiet of the Vietnam memorial or the majestic marble of the WWII memorial, the Korean shows real men who have been sent to an unhappy, uncertain task, then consigned to the shadows, in what history has since labeled “the forgotten war.”

No majestic slogans mark the monument; only the cautionary sentence “Freedom Is Not Free” serves to warn the visitor that every act undertaken by politicians and kings has a real cost for real men. That cost is also recorded on the monument, with the dead, wounded, captured and missing totaling 172,847 Americans, not to mention the losses of the other twenty-two United Nations members whose soldiers comprised the total war effort.

To stand at many of the National Mall’s war memorials is to deal in abstractions…..patriotism, truth, sacrifice…noble words, noble ideals. To stand at the Korean War Memorial is to feel the blood and bone of war, its terror and tension, its risk and reality. It is the greatest kind of public art, because the public are destined, always, to become a vital part of it.

In the line of fire.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

LIPSTICK ON A PIG

Bad day at the office: having failed at making this house charming, I then went on to also fail at making it sinister and forbidding. I did, however, succeed in making it an unholy mess.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S TV-DOCTOR SHOW CLICHE NUMBER ONE. The frantic ER crew valiantly works upon a patient who is coding, pulling out every tool in a desperate search for a discernible pulse. Then the close-up on the earnest nurse: “He’s gone.” and the final pronouncement by the exhausted resident: “Okay, anyone have the time? I’m calling it….”

That’s pretty much what it’s like to try to rescue a lousy photograph by extraordinary means…tweaking, sweetening, processing, whatever you call the ultimately futile emergency measures. Sometime the unthinkable is obvious: the picture’s a goner…no pulse, no soul, no life.

Cue Bones McCoy: It’s dead, Jim.

I have made my share of ill-advised interventions in the name of “saving” photos that I was unwilling to admit were lifeless, pointless, just a plain waste of time. You’ve done it too, I’m sure. Trying to give some kind of artistic mouth-to-mouth to an image that just wasn’t a contender to begin with. It was a bunch of recorded light patterns, okay, but it damn sure wasn’t a photograph. Smear as much lipstick on a pig as you want….it’s still a pig.

The above image shows the worst of this pathology. I wanted to show the charm of an old bed-and-breakfast in the gloriously beautiful little town of Pacific Grove, located just up the peninsula from Monterey in California (see image at left). But everything that could have made the image memorable, or even usable, was absent. The color, a cool buttercup yellow, is common to many town dwellings. In the warm glow of dawn or the late waning, dappled light of late afternoon, it can be charming, even warm. In the mid-day light, weak, withered. Then there was the total lack of a composition. The picture was taken in a second, and looked it.

So, angry at having failed at the “charming” look I had gone for, and unable to make the backlighting on the house work for me, I went into Photomatix (usually a very solid HDR tool) and started, almost angrily, to take revenge on the damned thing. If I can’t make you pretty, I’ll make you magnificently ugly, hahaha…. Seriously, I was pretty far into the journey from “happy little house” to “creepy little twilight creep castle” before realizing there was nothing to be extracted from this picture. No amount of over-glop, taffy-pulling or prayer would magically compensate for a central core concept that just wasn’t there. Like it or not, the pig was always going to show through the lipstick.

Sometimes you just gotta declare the unlucky patient in front of you dead, and try to save the kid on the next gurney over.

This blog was always supposed to be about choices, both good and bad, and how we learn from each. I have shared my failures before, and firmly believe that the only honest conversation comes from admitting that sometimes we make colossal errors in judgement, and that a fair examination of even our “misses” is more important than an endless parade of our “hits”.

Photography is not about consistent genius. It’s about extracting something vital from something flawed.

Being able to identify when we have fallen short is the most important skill, the most essential tool.

CAUGHT IN THE CROSSFIRE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE HAS BEEN A LOT OF MENTION, OF LATE, OF THE PHENOMENON KNOWN AS “PHOTOBOMBING“, the accidental or intentioned spoiling of our perfect Kodak moments by persons inserted into the frame at a crucial instant. Whether they block the bride’s face, eclipse Grandma’s beloved puppy, or merely pop up annoyingly behind the cute couple, they, and the images they ruin, are one of the hottest posting sources along the photo-internet galaxy right about now.

But fate photobombs us every day, and often drops a gift out of the sky, and into our pictures. The two-fold trick is to (a) be ready to improvise and (b) be grateful for the chance for something altogether different from what we originally conceived.

Happened to me several weeks ago. Total accident, since the thing I shot in the moment was not what I had started out for at all. Real simple situation:an underground walkway from one low-lying section of a city park to another, the sidewalk taking a short cut under a bridge. Overhead, six lanes of unheeding street-level traffic. Below, a concrete tunnel of sorts, with sunlight from the park illuminating either open end.

Oh, and the grate. Should mention that a section of the street overhead was, instead of solid roadbed, an open-pattern, structural steel grid, with dappled geometrics of light throwing a three-sided pattern of latticed shadows onto the side walls and floor of the tunnel below. Nice geometry. Now, I wasn’t looking to shoot anything down here at all. Like the chicken, I just wanted to get to the other side. But I had my wide-angle on, and a free light pattern is a free light pattern. One frame. A second, and then the bomb: a jogger, much more acquainted with this under-the-road shortcut than me, crossing from over my right shoulder and into my shot. Almost instinctively, I got her in frame, and relatively sharp as well.

Same settings as in the “jogger” frame, but a little colder minus the human element. A matter of taste.

Not content to have caught the big fish of the day, I took the opposite angle and tried again to recoup my “ideal shot”, minus the human element. But something had changed. Even so, I still needed a gentle nudge from Fate to accept that I had already done as well as I was going to do.

My battery died.

I limped home, then, during my upload, found that what I had been willing to reject had become essential. I wish it was the first time I’ve had to be taught this lesson.

But I’d be lying.

Photobombed by circumstance.

And grateful for it.

follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

WHAT’S YOUR TREE?

Detail of a restuarant that I’ve shot dozens of frames of, over the past five years. However, ask me if I could shoot it everyday for a solid year. I’m thinking not.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE MAN’S DEDICATION IS ANOTHER MAN’S OBSESSION. Whether we view a person as passionately committed or someone who should just be, well, committed is largely a matter of perception. Nowhere is this truer than in the artistic world. Walk into any gallery, anywhere, and you will engage with at least one fixation on excellence that you believe is proof that grant money is dispensed far too freely. If this were not so, there would only be the need for one artist. The rest of us would be manning xerox machines. That’s why some people believe Thomas Kincade was a prophet, while other believe he was just, well, a profit.

Usually these debates are accompanied by too many beers, more than a few elevations in volume, and at least one person who gets his feelings hurt. Such is life, such is expression. We just guarantee your right to try it. We don’t guarantee anyone’s obligation to buy it.

Discussion of the new book That Tree by Mark Hirsch (due in August) will fuel many such lager-lubricated chats, and some of them will be heated, I’m sure. The book actually demonstrates two separate obsessions, er, passions. First, Hirsch, a professional photographer, wished to create a substantial project for which he would set aside his Top Gun-level camera gear and shoot exclusively with his new iPhone. Second, early on in the project, he took the dare/suggestion from a friend to limit his subject matter to a single tree, an unremarkable bur oak that he had passed, without noticing, daily for almost nineteen years.

Discussion of the new book That Tree by Mark Hirsch (due in August) will fuel many such lager-lubricated chats, and some of them will be heated, I’m sure. The book actually demonstrates two separate obsessions, er, passions. First, Hirsch, a professional photographer, wished to create a substantial project for which he would set aside his Top Gun-level camera gear and shoot exclusively with his new iPhone. Second, early on in the project, he took the dare/suggestion from a friend to limit his subject matter to a single tree, an unremarkable bur oak that he had passed, without noticing, daily for almost nineteen years.

Think about this, now.

Looking back over the subjects that I personally have been drawn to revisit time and again, I’m damned if I can find even one with enough visual gold to warrant mining it for 365 images. the closest two subjects would be a small restaurant in Scottsdale, Arizona called Zinc Bistro, and the campus of cliffside art galleries at the Getty Center above Los Angeles. And I have cranked out a ton of frames of both subjects, looking for a truth that may or may not be there to see…but not a year’s worth. I personally believe that I might conceivably be able to find that much mystery and beauty in my wife’s face….in fact, I shoot her as often as I can. However, long before a project of this scope could be completed, she would have taken out a contract on my life. True love will only take you so far.

I have got to see this book.

Mark Hirsch will either become my new synonym for Latest Photo God Almighty or another amusing asterisk in the broad sweep of imaging history.He will also provide strong talking points for those who champion the iPhone as a serious photographic instrument. For that alone, the book has value.

Either way, it ain’t gonna be boring.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

Related articles

- Photographer documents a year in the life of a tree on his iPhone (guardian.co.uk)

THE GRADUAL REVEAL

by MICHAEL PERKINS

CREATING FANTASY IMAGES ON A TABLETOP IS A LITTLE LIKE WATCHING YOUR GRANDMA IN THE KITCHEN, if your grandma (like mine) was the “I-don’t need-no-recipe”,a dash here, a pinch there kind of cook. Sometimes I think she just kept chucking ingredients into the pot until it was either the right color or the correct thickness. All I know is, when she was done, it “ate pretty good”.

I use the same approach when I am building compositions from scratch. You’re not sure what the proportions are, but you kind of know when you’re done.

One of the photo sharing sites that I recommend most enthusiastically is called UTATA, a site which promotes itself as “tribal photography” since it require a certain level of communal kick-in from all its members, posing workshop assignments and themes that take you beyond merely posting your faves. Operating in tandem with its self-named Flickr group, UTATA is about taking chances and forcing yourself, often on a deadline, to see in new ways. If it sounds like homework, it’s not, and even if you have no time to work the various challenges, you’ll still reap a vast wealth of knowledge just riffing through other people’s work. Give it a look at http://www.utata.org.

One of the site’s recent so-called “weekend projects” was to photograph anything that in any way depicted broken glass. No special terms beyond that. Cheap glass, wine glass, churchy stained glass, pick your texture, pick your context. I decided to so something with a shattered light bulb, but with a few twists. Instead of just breaking the bulb and shooting a frame, I opted to place the bulb in a food storage bag, then hammer it until it burst. Due to the sudden release of pressure when light bulbs are breached, they don’t just crack, they sort of explode, and, given the chemical treatment of the glass, there is a lot of pure white dust that accompanies the very fine glass particles. Breaking the bulb inside the bag allowed me to retain all that sediment, then make it more visible by pouring the bits out onto a black, non-reflective surface…in this case, a granite tile that I use to model product shots on.

I already liked the look of all the atomized white dust across that dull blackness, rather like a “star field”, or a cluster of debris, scattered across a vast void in space. The effect was taking shape, but the “garbage cook” inside my head was still looking for one more ingredient. The great thing about building a fantasy visual is that it doesn’t have to make “sense”….it just needs visual impact sufficient to register with the gut. If the micro-fine bits of the bulb represented some kind of space catastrophe, where was the cause? Inner stresses, like volcanoes, rupturing the Mother Bulb asunder like the planet Krypton? No, wait, what if something collided with it, some asteroid-like something that spelled doom for Planet G.E.? A quick trip out to the back yard gave me my cosmic cataclysm….I mean chunk of quartz, and the rest was just arrangement and experiment.

What does it all mean? Heck, what does beef stew mean? Making a picture can be like gradually adding random veggies and spices until something tells you it’s “soup”. And with tabletop fantasies, you get to play God with all the little worlds you’ve created.

Hey, over a lifetime, plenty of other people will take turns blowing up your work.

Why not you?

follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.