PROOF POSITIVE (AND NEGATIVE)

How charming it would be if it were possible to cause these natural images to imprint themselves durably and remain fixed upon the paper! And why should it not be possible? I asked myself. –William Henry Fox Talbot

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IMAGINE THAT, IN ADDITION TO MAKING THE AUTOMOBILE PRACTICAL AND AFFORDABLE, Henry Ford had also been the world’s foremost racing driver. Or that Rembrandt had also invented canvas. The history of invention occasionally puts forth outliers who not only envision an improvement for the world, but become renowned as the best, first models for how to use it. The early days of photography saw several such giants, tinkerers who nudged the infant technique forward even as they became its first artists.

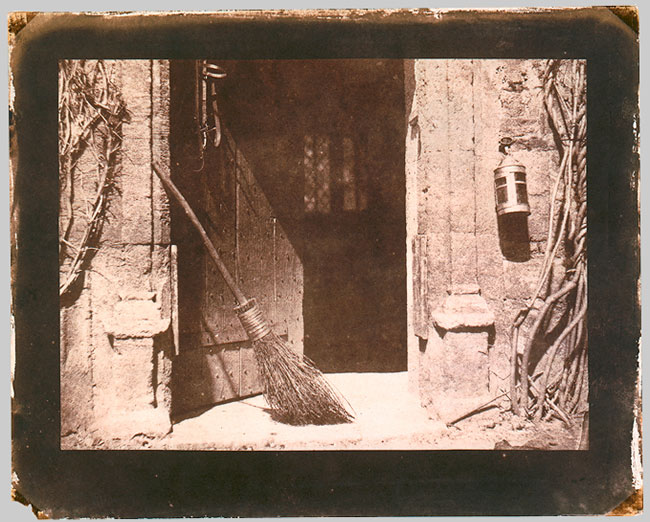

William Henry Fox Talbot, Trees And Reflections (1842). The master technician was also a masterful artist.

Unlike the telephone or the incandescent bulb, there was, for the camera, no single parent, but rather a series of talented midwives who massaged the young art from exotic hobby to mass movement, the most democratic of all art forms. Thus, William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) was not the first person to use light and chemistry to permanently fix and preserve images. But, without his contributions, printed photograph might never have evolved, nor would the negative, the easiest method for printing endless numbers of copies from a single master.

Talbot’s work began as a way to improve upon the daguerreotype, which dominated the photographic world in the early 1800’s and which was, as a positive image printed directly on glass, literally one of a kind, barring duplication or distribution. If photography were to be widely practiced, Talbot reasoned, a practical method had to be created to allow photos to be made from photos.

Talbot’s first attempts consisted of ordinary typing paper coated in a solution of salt and silver nitrate. The resulting silver-chloride mixture was highly sensitive to light, darkening as it was exposed, and registering the light and dark values of a subject backwards, as a negative. However, over the long exposures needed at the time, the darkening process often accelerated to make the image completely black, so Talbot had to experiment with other chemicals to render the process stable, to develop just so much and then stop. The next step was creating what would become the first chemical developers, allowing for shorter exposure times and more vivid images printed from his paper negatives.

Various refinements in the “calotype” process followed, along with a hash of bitter patent battles between Talbot and other inventors evolving similar systems. Interestingly, along the way, the need to demonstrate the superior results of his products had the accidental side effect of making Talbot himself one of the period’s most practiced early photographers, giving him equal influence over inventors and artists alike.

In time, Talbot’s calotype system would be further improved by coating glass with collodion, making for a sharper and more detailed negative from which to create prints. The final step toward universal adoption of photography would be George Eastman’s idea for a flexible celluloid-based film negative, the process that ushered in the age of the snapshot and put a camera in Everyman’s hands.

OFF-WHITES AND NEAR COLORS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST GRAPHIC DEMONSTRATIONS OF THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN YOUR EYE AND A CAMERA’S occurs by accident for most photographers, with variations in the reading of white balance that make the colors in an image look “wrong”. While our own vision looks at everything in the world from light blues to medium greys and instantly converts them all to “white”, the camera makes looks at all those variants and makes what can be called its best guess.

All light has a temperature, not a measure of heat but an index of which colors combine to deliver hues of a certain intensity and range, and white balance helps photographers manage color more effectively. Film shooters, especially those using sophisticated flash technology, eventually develop an instinct as to which kind of light will deliver the hues they seek, but, as the digital era tracks onward, many more of us simply rely on our camera’s auto settings to deliver a white that strikes us as “correct”. And when auto white balance fails to deliver the goods, we can override it and select other settings that compensate for incandescent light, shade, cloudy skies, and so forth. We can also create a completely custom white balance with little fuss. Think Dad looks better with a green face, like the true extra-terrestrial that he is? It’s at your fingertips.

The fun starts when you use white balance to depart from what is “real” in the name of interpretation. WB settings are a fast and easy way to create dramatic or surreal effects, and, when you have enough time in a shoot to experiment, you may find that reality can be improved upon, depending on what look you want. In the top image, taken during a long, lingering sunset at sea, I had plenty of time to see what my camera’s custom WB settings might create, so I bypassed standard auto WB, then amped up the reds in the sky by clicking over to a shade setting, resulting in a deep and warm look.

For the second shot of the same scene, I wanted to simulate the look of a sky just after sunset, when the blues of early evening might take over for the vanished sunlight, even providing a little radiance from a pale moon. One click to the setting and you see the result. Now, of course, I’ve just switched from one simulation of reality to another, but playing with WB in a variety of lighting situations can help you tweak your way to fantasy land with no muss or fuss.

Tweaking white balance is basically lying to your camera, telling it that it is not seeing what it think’s it’s seeing but what you want it to think it sees. You’re the grown-up, you’re in charge. “White” is what you say it is. Or isn’t.

FRINGE ELEMENT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE RESURRECTION, ABOUT TWENTY-FIVE YEARS AGO, of several low-end, cold-war-era plastic cameras as refurbished instruments of a kind of instinctual “art” photography has influenced even the digital and high-end photo markets, with light-leaking, optically sloppy toys like the Holga, the Diana and other “lomographic” devices shaking up the way many photographers see the world. Thus have these technically challenged little cameras, designed as children’s playthings, changed the conversation about what kind of formerly dreaded optical flaws we now elect to put back in to our work. Lomo shooters’ devotion to their craft has also meant a reprieve of sorts for film, since theirs in an analog realm.

But even digital shooters who don’t think of themselves as part of the “lomography” trip can dip a toe into the pool if they like, with filters on phone apps labelled “toy camera” which simulate light leaks, film-era “cross-processing” and the color variations caused by cheap plastic lenses. There are also companies like Lensbaby that manufacture all-new plastic optics designed to lend an element of creative control to what, in lomo cameras is largely random. The good news: you can, in effect, put defects into your pictures….on purpose.

Plastic lenses are generally much softer than glass lenses, giving a kind of gauzy appearance to your shots, so if you’re a fan of razor sharpness, they may not be your dish. More importantly, they produce a much higher amount of what is called “chromatic aberration”, which is more understandable under its nickname “color fringing”, since that more accurately describes how it looks. If you want a reasonably clear science-guy breakdown of CA, here’s a link to keep you busy this semester. The main take-home for most of us, though, is that the effect takes what would largely be a smoothly blended rendering of colors and makes them appear fractured, with the “fringe” look most noticeable along the peripheral edge of objects, where the colors seem to be separating like the ragged edge of an old scarf.

Why should you care? Well, mostly, you don’t have to. All lenses have a degree of CA, but in the better-built ones it is nearly undetectable to the naked eye, and can be easily processed away in Lightroom or a host of other editing suites. But people who are choosing to use plastic lenses will see it quite clearly, since such optics cause different wavelengths of light to “land” in the focal plane at slightly different speeds, meaning that, in essence, they fail to smoothly blend, hence the “fringing” effect.

Of course, chromatic aberration may be exactly the look you’re going for, if you want to create a kind of lo-fi, primitive look to your shots. In the cactus photo seen here, for example, taken with an all new plastic “art” lens, I found that the effect resembled old color printing processes associated with early postcards, and, for that particular image, I can live with it. Other times I would avoid it like the plague.

Plastic lenses, like any other add-ons or toys, come with their own pluses and minuses. Hey, if you’re a ketchup person, then soak your plate with the stuff. But if you believe that it just louses up a good steak, then push the bottle away. Just that simple.

BEST OF TIMES, WORST OF TIMES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I OFTEN FANTASIZE ABOUT STANDING UP AND OFFERING A TOAST at a banquet hall crammed with photographers, just because it’s fun to play with what it might sound like….to see if I could strike some verbal chord that would resonate equally with everyone in the room, from the noobies to pro’s. I constantly change the exact wording, but the sentiment in my head is always something like:

May the best picture you took today be your worst picture ever, ten years from now.

What did he say? Does he hope the masterpiece I captured today will someday be regarded by me as garbage?

Well, yes, of course I do. At least I hope that for my stuff. If I still love today’s work ten years from now, it will mean that I stopped growing and learning, like, well, today. Consider: I can’t ever know everything about my craft, and can’t hope to “top out” or reach perfection within my lifetime. And why would I want to? If today is the best I’ll ever do, why not save time and money, smash my cameras, and consider myself done?

The entire point of artistic expression is that it is an evolutionary process. If I still took pictures the way I did at twelve, that would be like having been on a Ford assembly line for half a century, with one indistinguishable cog after another coming down the belt, and me adding the same screw to it, every day, for eternity. Photography appeals to us because, like any other measure of our mind, it will be in flux forever. It’s divinely uncertain.

And I want that uncertainty. I want the good shots that come on lousy days. I need the images that I made when I had no idea what I was doing. I crave the betrayals that camera bodies, lenses, changing weather conditions or cranky kids will hurl at me. Edward Steichen often referred to the act of refreshing one’s work as “kicking the tripod”, and, like that seismic shock, your own morphing ideas of how to do all this will benefit from an occasional earthquake.

Do great pictures always come from adversity? Of course not, or else my morbidly depressed friends would be the greatest photographers on earth. However, the sheer careening instability of life pretty much guarantees that the things that thrill you about today’s shots will make you shake your head ten years down the line, and devise different ways of solving all the eternal problems.

And so, a toast…to the great pictures you made today, and to the day that you can barely stand to look at them.

WORKHORSES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHAT MAKES A LENS GREAT, AT LEAST FOR ME, is the degree to which I can forget about it.

The best images come from being able to shoot decisively and in the moment. That means knowing instinctively what your lens is good at, and using that information to salvage more pictures. Such knowledge only comes from repetition, trial and error, patience, and all those other tedious old-school virtues that drive people crazy but drive their work to perfection. And, eventually, it means you and the lens must think and react as one, without a lot of conscious thought.

I only know one way to get to that point with a given piece of glass, and that’s to be “monogamous” with it, using a given lens for nearly 100% of my work for long periods of time. Shuffling constantly from lens to lens in an effort to get “just the right gear” for a particular frame actually leads me to be hyper-conscious of the limits or strengths of what I’m shooting with, to be less focused on making pictures and more focused on calculating the taking of pictures. I believe that the best photos start coming the closer you can get to a purely reflexive process. See-feel-shoot.

If you’ve never chosen your own version of a “go-to” lens, one that can stay on your camera almost always, and give you nearly every kind of shot, I would suggest biting off a fat space of practice time and trying it. Snap on a 35mm and make it do everything that comes to hand for a day. Then a week. Then a month. Then start thinking of what would actually necessitate taking that lens off and going with something else. And for what specific benefit?

You may find that it’s better getting 100% comfortable with one or two lenses than to have a passing acquaintance with six or seven. The above image could have been taken with about five different lenses with comparable results. But whatever lens I used, it would have been easier and faster if I had selected it because it would also work for the majority of the other shots I was to attempt that day. Less time rummaging around in your kit bag equals more time to take pictures.

Every time there is a survey on what the most popular focal length in photography is, writers tend to forget that the number one source of imagery today is a cell phone camera. That means that, already, most of the world is shooting everything in the 30-35mm range and making it work. And before we long for the “good old days” of infinite choices, recall that most photographers born before 1960 had one camera, equipped with one lens. We like to think we are swimming in choices but we need to make sure we’re not actually drowning in them.

Find the workhorse gear that has the most flexibility and reliability for what you most want to do. Chances are the lens that will give you the best results isn’t the shiny new novelty in the catalogue, but just inches away, right in your hand.

OKAY, THAT’S NOT A COMPLIMENT….

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS, LIKE ALL OTHER UPRIGHT BIPEDS, LOVE PRAISE. None of us are so jaded that we don’t like to get a gold star for an image or an idea; after all, that’s why we do this. However, as borne out by the simplest Google research, there is one sentence, which, although intended as a compliment, will send the average photographer into a seething simmer. You’ve heard it. Maybe you’ve even said it.

Repeat it with me:

Gee, your pictures are so good. You must have a really great camera.

Sadly, this sentence is intended as a thumbs-up, a certification that “ya done good”. However, it unfortunately lands on the ear sounding like, “Lucky you. Despite your basic, hapless ineptitude, the magical machine in your fist created art that was so wonderful, not even a clod like you could prevent it from happening.Congrats!”

When I am told that my pictures are good because I have “a really good camera”, part of me wants to extend the idea of tools=talent to other fields of endeavor, as in:

“Thanks. I can hardly wait to buy a $3,000 oven so I can become a master chef.”

“Thanks, I’m eager to get some $200 brushes so I can paint a masterpiece.”

“Thanks. I’m planning to tie a blanket around my neck and recite ‘I’m Batman’ several thousand times so I can be a crimefighter….”

Photography isn’t about tools. It’s about patience, perseverance, vision, flexibility, humility, objectivity, subjectivity, and, most importantly, putting in more hours than the next guy. It’s about exercising your eye as you would any muscle that you’ve like to tone and strengthen. It’s about sitting 24 hours in a duck blind, hanging by your heels from a helicopter, avoiding incoming gunfire, charming grumpy children, and learning to hate things in your own work that, just yesterday, you believed was your “A” stuff.

If equipment were all, then everyone with a Steinway would be Glenn Gould and everyone with a Les Paul Gibson would be, well, Les Paul. But we know that there is no success guarantee that comes with a purchase warranty. Many cameras are great, but they won’t wake you up at 4am to flush out a green-tailed towhee or climb a mountain to help you snag a breathtaking sunrise. Tools are not talent. And the sooner we learn that, the less we’ll start thinking our work will start to shine with the next new shiny thing we buy, and teach ourselves to make better pictures with what we own and shoot right here, right now.

THE FUTURE’S SO BRIGHT, I GOTTA WEAR SHADES

This shot is a snap (sorry) with available light and today’s digital sensors. 1/100 sec., f/5.6, ISO 250, 20mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS A GLOBAL RACE, ACCELERATING RAPIDLY SINCE THE DAWN OF THE DIGITAL AGE, toward better, faster image sensors in cameras great and small, as we wage the eternal photographic battle against the limits of light. It’s one more reason why this is the best time in the medium’s history to be making pictures.

It’s hard to express what a huge game-changer this is. Film-based photography advanced the science of gathering light in slow fits and starts for more than a century, with even some of the most popular consumer films rated at very slow speeds (Kodachrome) or, if faster, extraordinarily high grain (Tri-X). Suddenly, the world’s shadowy interiors, from stadiums to basements, give up their secrets to even bargain-priced cameras as ISO ratings for sensors climb and noise/grain abatement gets better and better.

The above image, taken inside the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, would have, in film terms, required either a full-open aperture (making a consistent depth of field from front to back tricky), a slow exposure (hard to go handheld when you’re on a tour) or a film rated at 400 or above. Plus luck.

By contrast, in digital, it’s a casual snap. The f/5.6 aperture keeps things sharp from front to back, and the ISO rating of 250 results in noise that’s so low that it’s visually negligible. The statue of television pioneer Philo Farnsworth is dark bronze, and so a little re-contrasting of the image was needed in post-editing to lighten up the deeper details, but again, the noise is so low that it’s really only visible in color. As it happens, I actually like the contrast between the dark statue and the bright room better in monochrome anyway, so everyone wins.

The message here is: push your camera. Given today’s technology, it will give you some amazing things, and the better you understand it the more magic it will produce. We are just on the cusp of a time when we can effectively stow the flash in the closet except in very narrow situations and capture stuff we only used to dream about. Get out there and start swinging for the fences.

THE SINGLE BULLET THEORY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

Okay, Wang, I think that’s enough pictures of the parking lot. —Rodney Dangerfield, Caddyshack

IF YOU WERE TO EXPRESS TODAY’S PHOTOGRAPHIC FREEDOM IN TERMS OF FIREPOWER, it would be fair to say that many of us have come to shoot in a somewhat scatter-shot fashion, like someone sweeping a machine gun. Indeed, digital allows us to overshoot everything to such a degree that doing so becomes our default action, because why would you take one picture of your child digging into birthday cake when fifty will do just as well?

Some over-shooting is really what pro photogs used to call “coverage” and is actually beneficial for particularly hard subjects. Awe-inspiring sunsets. A stag at bay. The fiery burst from a Hawaiian volcano. Such subjects actually warrant a just-one-more approach to make sure you’ve thought through every possible take on something that can be interpreted in a variety of ways, or which may be vanishing presently. But that’s a lot different from cranking off four dozen clicks of the visitor’s center at Wally World.

Shooting better isn’t always assured by merely shooting more. Instead of the machine gun technique, we might actually improve our eye, as well as our ability to strategize a shot, by limiting how many total tries we make at capturing an image. My point is that there are different “budgets” for different subject matter, and that blowing out tons of takes is not a guarantee that Ze Beeg Keeper is lurking there somewhere in the herd.

So put aside the photographic spray-down technique from time to time and opt for the single bullet theory. For you film veterans, this actually should be easy, since you remember what it was like to have to budget a finite number of frames, depending on how many rolls you packed in. Try giving yourself five frames max to capture something you care about, then three, then one. Then go an entire day taking a single crack at things and evaluate the results.

If you’ve ever spent the entire day with a single focal length lens, or fought severe time constraints, or shot only on manual, you’re already accustomed to taking a beat, getting your thinking right, and then shooting. That’s all single-take photography is; an exercise in deliberation, or in mindfulness, if you dig guru-speak. Try it on your own stuff, and, better yet, use the web to view the work of others doing the same thing. Seek out subjects that offer limited access. Shoot before your walk light goes on at an intersection. Frame out a window. Pretend an impatient car-full of relatives is waiting for you with murder in their hearts. Part of the evolution of our photography is learning how to do more with less.

That’s not only convenient, in terms of editing. It’s the very soul of artistry.

NEW WINE FROM OLD BOTTLES

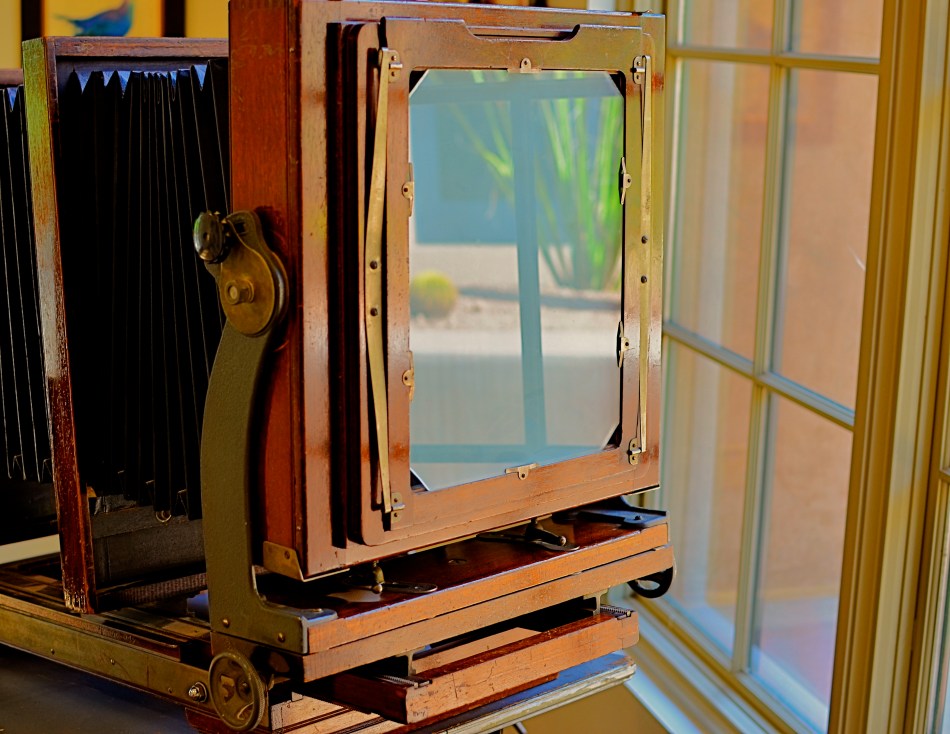

Wide-angle on a budget, and in a time warp: a mid-70’s manual 24mm Nikkor prime up front of my Nikon D5100.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MANY OF US WHO BEGAN THEIR LOVE FOR PHOTOGRAPHY IN THE DAYS OF FILM have never really made a total switch to digital. It just never was necessary to make that drastic a “clean break” with the past. Far from it: through the tools and techniques that we utilized in the analog world, we still carry forth viewpoints and habits that act as foundations for the work we produce in pixels. Photography was not “re-invented” by digital in the way that transportation was when we moved from horse to car. It was refined, adding a new chapter, not an entire book.

Digital is merely the latest in a historical line of ever-evolving recording media, from daguerreotypes to salted paper to glass plates to roll film. The principles of what makes a good picture, plus or minus some philosophical fashion from time to time, have not changed. That means that tons of toys from the analog world still have years of life left in them, especially lenses.

Call it a “reverse hack” mentality, call it sentiment, but some shooters are reluctant to send all their various hunks of aged camera glass to the ashcan simply because they were originally paired with analog bodies. Photography is expensive enough without having to start from scratch with all-new components every time a hot new product hits the market, and many of us look for workarounds that involve giving a second life to old lenses. New wine from old bottles.

Some product lines actually engineer backwards-compatibility into their lenses. Nikon was the first and best company to spearhead this particular brain flash, making lenses for over forty years that can be pressed into service with the latest Nikon body off the production line. In my own case, I have finally landed a Nikon 24mm f/2.8 prime, not from current catalogues, but from the happy land of Refurbia. It’s a 1970’s-era gem that is sharp, simple, and mine-all-mine, for a fifth of the cost of the latest version of the same optic.

My new/old 24 gives me a wide-angle that’s a full stop more light-thirsty than the most current kit lenses in that focal length, and is also small, light, and quick, even as a manual focus lens. And it can be argued that the build quality is better as well. Photography is about results, not hardware, so how you get to the finish line is your business. And yet, sometimes, I must admit that shooting new pictures with legendary lenses feels like photography, as an art, is building on, and not erasing, history.

THE EYE BACK OF THE LENS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY YEAR AT THIS TIME, AS I HIT THE RESET BUTTON ON MY LIFE VIA SOME KIND OF BIRTHDAY RITUAL, I pause to wonder, again, whether I’ve really learned anything at all in over fifty years of photography. Surely, by this late date, the habit of shooting constantly should have assured me that I had “arrived” at some place in terms of viewpoint or style, right? And yet, I still feel as if I am just barely inches off the starting line in terms of what there is left to learn, and how much more I need to know about seeing. It’s a great feeling in that it keeps things perpetually fresh, but I often wonder if I’ll ever make it to that mirage I see ever ahead of me.

The aging process, and how that continually remaps your perception, is one of the least pondered areas of criticism as it pertains to photography. And that’s very strange. We track the evolution of technical acuity over a lifetime. We date ourselves in reference to a piece of equipment we acquired, an influential person who crossed our path, or a body of work, but we don’t thoroughly examine how much our photography is being changed completely because the person making the picture is in constant flux. How can we ignore what seems to be the biggest shaper of our vision over time? We don’t even want the same things in an image from one year to the next, so how can we take photos in our maturity anything like those we shot in our youth?

Looking back to my first images, it’s clear that I thought the mere opportunity for a picture plus the act of clicking a shutter would result in a good picture, a kind of “cool view+camera=art” equation. This is to say that, instead of thinking, “I could make a good picture from this”, I was actually thinking, “this would be a good picture.” I know that sounds like hair-splitting of the first order, but the two statements are, in fact, different. The first implies that the camera plus the subject will automatically result in something solid; it’s a snapshot philosophy. The second statement is made by someone who has been frustrated by so many snapshots that he knows he has to step into the process as an active player. That realization can only come with age.

As always, my father’s admonition that art is a process rather than a product emerges as my prime directive. When I look at the pictures made by a twelve-year old me, I can at least see what the little punk was going for, and I can measure whether I’ve gotten any closer to that ideal than he did. The trick is for old me to want it as badly as young me did, and when that happens, I forget how many candles are on the cake, and am just grateful that their light still burns brightly.

THE VANISHED NORMAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE FUTURE DOESN’T ARRIVE ALL AT ONCE, just as the past doesn’t immediately vanish completely. In terms of technology, that means that eras kinds of smear across each other in a gradual “dissolve”. Consider the dial telephone, which persisted in various outposts for many years after the introduction of touch-tone pads, or, more specifically, Superman’s closet, the phone booth, which stubbornly overstayed its welcome long past the arrival of the cel. The “present” is always a mishmosh of things that have just arrived and things that are going away. They sort of pass each other, like workers at change of shift.

Photographically, this means that there are always relics of earlier eras that persist past their sell-by date. They provide context to life as part of a kind of ever-flowing visual history. It also means that you need to seize on these relics lest they, and their symbolic power, are lost to you forever. Everything that enjoys a brief moment as an “everyday object” will eventually recede in use to such a degree that younger generations couldn’t even visually identify it or place it in its proper time order (a toaster from 1900 today resembles a Victorian space heater more than it does a kitchen appliance).

Ironically, this is a double win for photographers. You can either shoot an object to conjure up a bygone era, or you can approach it completely without context, as a pure design element. You can produce substantial work either way.

Some of the best still life photography either denies an object its original associations or isolates it so that it is just a compositional component. The thing is to visually re-purpose things whose original purpose is no longer. Photography isn’t really about what things look like. It’s more about what you can make them look like.

LEFTOVERS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FAR BE IT FROM ME TO DO A HATER NUMBER on photographic post-processing. We often pretend that the act of photo manipulation began at the dawn of the pixel age, when, of course, people have been futzing with their images since the first shutter snapped. We love the idea of “straight out of the camera” as an ideal, but it’s just that…an ideal. Eventually, it’s the way processing is executed in a specific instance which either justifies or condemns its use.

With that in mind, I do find that too many of us use faux b&w, or the desaturation of color images, long after they’re snapped, as a kind of last-ditch attempt to save pictures that didn’t have enough force or impact in the first place. Have I resorted to this myself? Oh, well, yeah, maybe. Which means, freaking certainly. Have I managed to “save” many images in this way? Not so much. Usually, I feel like I’m serving leftovers and trying to pawn them off as a fresh meal.

Up In Your Grille, 2015. A mere b&w conversion from color would have flattened out many of this image’s tones.

The further along I lope through life, however,the more I tend to believe that the best way to make a black and white image is to set out to intentionally do just that. An act of planning, pre-visualization, deliberation. It means looking at your subject in terms of how a color object will register over the entire tonal range of greys and whites. Also, texture, as it is accentuated by light, is particularly powerful in monochrome, so that part needs to be planned as well. Exposure, as it’s effected by polarizers or colored filters also must be planned, as values in sky, stone or foliage must be anticipated. And, always, there is the use of contrast as drama, something black and white does to great effect.

You might be able to convert a color shot into an even more appealing b&w shot in your kerputer, but the most direct route, that is, making monochrome in the moment, is still the best, since it gives you so many more options while you’re managing every other aspect of the shot in real time. It all comes down to a major philosophical point about photography, which is that the more control you can wield ahead of the click, especially with today’s shoot-it-check-it-shoot-it-again technology, the better your results will be.

THE TRIANGLE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WINTER IS A TIME OF MUTED COLORS, DIMINISHED SUNLIGHT and inner struggle. I’ve heard people refer to the leaner, darker months as the feeling of being shut up inside a box, almost like having yourself placed in storage. I would lop one side off of that polygon and say that, to me, it feels more like being locked in a triangle.

As a photographer, I feel as if, in winter, I sustain three distinct emotional “hits” about my work, forming the three sides of the triangle, all three pressing up against, and balancing, each other. These sides can be described as:

Not enough new or compelling ideas coming into my brain. A case of the “drys”.

Too much re-evaluation of all of my images that failed, along with a big fat dose of recrimination.

A near-crippling sadness over the photographic opportunities, many tied to people now departed, that I simply didn’t act upon, and which are now lost to me forever.

The first side of the triangle really isn’t unique to winter-time. I experience  fallow periods throughout the year. They just ache more when amplified by slate-gray skies and dead trees. The second is to be expected, since spending more time indoors means rifling through old boxes of prints and slides, asking myself what the hell I was thinking when I chose this exposure or that subject, and ending the entire process by pitching some of those boxes into the incinerator. A needed exercise, but hardly anyone’s idea of a fun time.

fallow periods throughout the year. They just ache more when amplified by slate-gray skies and dead trees. The second is to be expected, since spending more time indoors means rifling through old boxes of prints and slides, asking myself what the hell I was thinking when I chose this exposure or that subject, and ending the entire process by pitching some of those boxes into the incinerator. A needed exercise, but hardly anyone’s idea of a fun time.

No, it’s the third side of the triangle which is the real killer, since the photos that haunt you the worst are always the ones you didn’t take. Friendships pour additional salt into this particular wound, since, somehow, you never recorded quite enough of the faces which once were the common features of your world, and which time has, one by one, erased.

Your own personal list of pals-not-present grows steadily over the years, and the thought that you could have shot one less sunset to capture just one more portrait of some of them hurts. It’s not as if your emotional souvenirs of them aren’t burned into your mind’s eye. It’s not even that you might have done something magical or singular with their faces beyond another birthday candid. It’s simply that once you could, and now you can’t.

The triangle isn’t all torture. Breaking out of it means taking arms against ghosts, and (as Shakespeare said), by opposing, ending them. You not only have to keep shooting, but keep shooting mindfully. Because when all of this that we call reality finally drains through our fingers, the scraps of it that we leave behind really can matter. Even with triangles, there’s always one more side to the story.

THE CHOICE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ANYONE WHO REGULARLY VISITS THESE PAGES already knows that I advocate of doing as much of your photography in as personal and direct a way as possible. While I am completely astonished by the number of convenience items and automatic settings offered to the casual photographer in today’s cameras, I believe that many of these same features can also delay the process by which people take true hands-on control of their image-making. I regard anything that gets in between the shooter and the shutter as a potential distraction, even a drag on one’s evolution.

Tools are not technique. Here are two parallel truths of photography: (1) some people with every gizmo in the toy store take lousy pictures. (2) some people with no technical options whatsoever create pictures that stun the world.

From my view, you can either subscribe to the statement, “I can’t believe what this camera can do!” or to one which says, “I wonder what I can make my camera do for me!” The very controls built into cameras to make things convenient for newcomers are the first things that must be abandoned once you are ready to move beyond newcomer status. At some point, you learn that there is no way any camera can ever contain enough magic buttons to give you uniformly excellent results without your active participation. You simply cannot engineer a device that will always deliver perfection and perpetually protect you from your own human limits.

Innovators never innovate by surrounding themselves with the comfortable and the familiar. For photographers, that means making decisions with your pictures and living with the uneven results in the name of self-improvement. This is a challenge because manufacturers seductively argue that such decisions can be made painlessly by the camera acting alone. But guess what. If you don’t actively care about your photos, no one else will either. There may not be anything technically wrong with your camera’s “choices”. But they are not your choices, and eventually, you will want more. The structure that at first made you feel safe will, in time, start to feel more like a cage.

Tools are not technique.

THOU SHALT….

By MICHAEL PERKINS

BOY HOWDY, DO WE LOVE LISTS. Classifications. Stratifications. Ranks. Pecking Orders. Best Of. Worst Of.

Books you need to read before you die (how could you read them otherwise?). The Ten Biggest Errors in The Phantom Menace (not counting the error in making it in the first place). Guinness Records. Pillsbury Bake-Off Finalists. The number of times Burt Ward said “Holy”-something in Batman. And, for photographers, the inevitable (and ubiquitous) lists of Most Common Photographic Mistakes.

You’ve read ’em. I’ve read ’em. We both probably have actually learned something from one or another of them. And yet, I find something strangely consistent in most of these lists; they nearly all address technical issues only. Everything from selecting the perfect depth-of-field to a kindly reminder to remove your lens cap, but very, very little about the deciding factor in all great photographs, namely, having something to say. Tech tutorials are constantly torturing themselves into tabulated commandments, all the “thou shalts”, but it is rare that the aesthetic issues, the “why shoot?” arguments, are given equal billing. This impoverishes the literature of an art that should be more about intentions and outcomes than gear or settings.

If there has been any one bonanza from the democratization of photography (through smart phones, lomography, etc), it’s been the stunning reminder that your camera doesn’t matter as much as what you can wring out of it. Eventually we’ll be able to interface with our own senses, literally taking a picture in the wink of an eye (or the sniff of a nose, if you prefer), and, with every other device used before that to freeze time, it will rise or fall with the input of the photographer’s mind/heart. If equipment was the only factor that could confer photographic greatness then only rich people would be photographers, but that is obviously not the case.

With that in mind, lists of do’s and don’ts for photographers that only focus on the technical are (1) sending the erroneous message that only the mastery of technology is necessary for great pictures, and (2) ignoring the x-factor in the human spirit that truly makes the pictures come forth. If you can obey all the “thou shalts” and still make lousy images (and you can), then you know there is something else missing.

ON THE SOFT SIDE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE WORLD’S FIRST MOVIE STUDIO WAS A TARPAPER SHACK ON A TURNTABLE. Dubbed by Thomas Edison’s techies as “The Black Maria” (as ambulances were grimly named back at the time), the structure rotated to take advantage of wherever sunlight was available in the California sky, thus allowing the film crew to extend its daily shooting schedule by more than half in the era of extremely slow film stocks. Eventually artificial light of sufficient strength was developed for the movies, and actors no longer had to brave motion sickness just to rescue fair damsels. So it goes.

More than a century hence, some photographers actually have to be reminded to use natural light, specifically window light, as a better alternative to studio lights or flash units. Certainly anyone who has shot portraits for a while has already learned that window light is softer and more diffuse than anything you can plug in, thus making it far more flattering to faces (as well as forgiving of , er, flaws). It’s also good to remember that it can lend a warming effect to an entire room, on those occasions where the room itself is a kind of still life subject.

Your window light source can be harsher if the sun is arching over the roof of your building toward the window (east to west), so a window that receives light at a right angle from the crossing sun is better, since it’s already been buffered a bit. This also allows you to expose so that the details outside the window (trees, scenery, etc.) aren’t blown out, assuming that you want them to be prominent in the picture. For inside the window, set your initial exposure for the brightest objects inside the room. If they aren’t white-hot, there is less severe contrast between light and dark objects, and the shot looks more balanced.

I like a look that suggests that just enough light has crept into the room to gently illuminate everything in it from front to back. You’ll have to arrive at your own preferred look, deciding how much, if any, of the light you want to “drop off” to drape selective parts of the frame in shadow. Your vision, your choice. Point is, natural light is so wonderfully workable for a variety of looks that, once you start to develop your use of it, you might reach for artificial light less and less.

Turns out, that Edison guy was pretty clever.

WHEN TEXTURE IS THE TALE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THOSE WHO BELIEVE THAT SUBJECT MATTER IS KING IN PHOTOGRAPHY ARE FACED OFF in an endless tennis match with those who believe that only impressions, not subjects, are the heart of the art. Go away for fifty or sixty years and they are still volleying: WAP! a photograph without an objective is a waste of time! WAP! who needs an object to tell a story? Emotional impact is everything! And so on. Pick your side, pick your battle, the argument isn’t going anywhere.

Thing is, my assertion is that you don’t actually have to choose a side. Just let the assignment at hand dictate whether subject or interpretation is your objective. There are times when the object itself provides the story, from a venerable cathedral to an eloquently silent forest. And there are times when mere color, light patterns, or texture are more than enough to tell your tale.

Set Your Face Like Flint, 2014. Shot wide at 18mm, cropped to square format. 1/100 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100.

I find, for example, that texture is one of my best friends when it comes to conveying a number of important things. The passage and impact of time. The feel and contour of materials, as well as the endless combinations and patterns they achieve through aging and weathering. A way to completely redefine an object by getting close enough to value its component parts instead of viewing it as a whole. This is especially true as I try to refine my approach to images of buildings. I find that breaking the overall structure into smaller, more manageable sections helps to amplify texture, to make it louder and prouder than it might be if a larger scene just included the entire building among other visual elements. Change the distance from your story and you change the story itself.

This Massachusetts barn has tons of character whether seen near or far, but if I frame it to eliminate anything but the raw feel of the wood, it demands attention in a completely different way. It asks for re-evaluation.Contrast the rough-sawn wood with the hard red of the windows,and, again, you’ve boosted the effect of the coarser texture. Opposing textures create a kind of rudimentary tug-of-war in a picture, and the more stark the contrasts, the more dramatic the impact.

Traditional, subject-driven story telling will dictate that you show the entire barn, maybe with surrounding trees and a rolling hill or two. Abstracting it a little in terms of color, distance and texture just tell the story in a distinct way. Your camera, your choice.

ROLL PLAYING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I RECENTLY CAME ACROSS AN ARTICLE IN WHICH A PHOTOGRAPHER BEMOANED the insane volume of images being shot in the digital era. His point was that, while we used to be tightly disciplined in the “budgeting” of shots back in the days of film (in which we had a fixed limit on our shots of 24 or 36 frames), we crank away an infinite number of shots today in short order, many of them near duplicates of each other, flooding the universe with a torrent of (mostly) bad pictures. Apparently, he posits, it is because we can shoot and re-shoot without fear of failure that we make so many mediocre images.

He takes it further, proposing that, as a means of being more mindful in the making of our photos, that we buy a separate memory card and shoot a total of, say, two “rolls” of pics, or 72 total images, forcing ourselves to keep every image, without deletions or retakes, and live with the results for good or ill. I have all kinds of problems with this romantic but basically ill-conceived stunt.

Our illustrious writer and I live on different sides of the street. He seems to believe that the ability to shoot tons of images leads to less mindful technique. I believe the exact opposite.

Not the hardest shot in the world, but in the film era, I might never have guessed how best to nail it. In digital, I was free to approach the right solution over a series of practice shots.

When you are free, via digital photography, to experiment, to correct your errors on the fly, you suddenly have the ability to save more shots, simply because you can close in on the best method for those shots much faster, and at a fraction of the cost, of film. You collapse a learning curve that used to take decades into the space of a few years. One of the things that used to separate great photographers from average ones was the great shooters’ freedom, usually from a financial standpoint, to take more bad (or evolving) images than the average guys could afford to. Of course, really bad photographers can go for years merely continuing to take more and more lousy shots, but the fact is, in most cases, taking more photos means learning more, and, often, eventually making better pictures.

Apparently, our illustrious writer believes that you can only be photographically self-aware if you are constantly reminded how few total frames you’re going to be able to shoot. I truly appreciate the goal of self-reliant, experience-based photography he wants to promote. But I contend that it’s not that we make too many pictures, but that we keep too many. It’s the skill of editing, that unemotional, ice-cold logic in deciding how few of our pictures are “keepers”, that is needed, not some nostalgic longing for the strictures of film.

Hey, of course we over-share too many near-identical frames of our latest ham sandwich. Of course Instagram is as clogged as a sink trap fulla hair with millions of pictures that should never see the light of day. But that’s not because we can shoot pictures too easily. It’s because we don’t grade our output on a stern enough curve. As it gets easier to shoot, it should get tougher to meet muster.

THE PICTURES I HATE MOST

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN MY CHILDHOOD, I FIRST HEARD THE BIBLICAL PARABLE OF THE SHEPHERD who, upon finding that one of his flock of one hundred sheep had gone missing, forsook the other ninety-nine to undertake a desperate search for the single lost lamb. It was, certainly, a touching story, with its image of a father who would mourn over the loss of even the most wayward of his flock. And, although it didn’t occur to me at the time, it also came to serve as an early model for my idea of a photographer.

It’s not really that big a stretch. Like the shepherd, shooters always mourn the loss of the one that got away, or in terms of photographs, the shot that was never made. The one angle we forgot to foresee, the light we failed to read, the fleeting truth we neglected to capture. For sure, the photos you attempted and botched really do smart, a lot. A lot a lot. However, there is no pain like the emotional toothache caused by the shots that, for whatever reason, you never even tried to make. These aren’t “lost” images, since they never actually existed, but that doesn’t mean that their absence is any less poignant. One great recent examination of why we fail to shoot is found in a recent collection of essays by Will Steacy called Photographs Not Taken. Check out a capsule review of it here.

I lament the pictures I never made far more than the ones I have attempted and whiffed, since in most cases the contexts that surrounded those non-existent pics are, themselves, no longer, whether we’re talking about missed sunrises or final visits with loved ones. To be sure, re-dos are often off the table even for many of the pictures we did take, but, for some human reason, we mourn more intensely the ones that might have been. Worse yet, even failed images have some teaching value, whereas you learn zilch from the dances that you sat out.

This forum has never been about merely posting my greatest hits for the world to drool over. That is scrapbooking, and serves no purpose. Any honest examination of why we make images has to pause to grieve about failed chances, to sniffle a bit over the things we aimed at and missed. It sometimes has to be about pictures that I hate, and the ones I hate most are the ones I had neither the vision nor the nerve to create.

CAUSE AND EFFECT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE’S NOTHING WORSE THAN COMING HOME FROM A SHOOT realizing that you only went halfway on things. Maybe there was another way to light her face. Did I take a wide enough bracket of exposures on that sunset? Maybe I should have framed the doorway two different ways, with and without the shadow.

And so on. Frequently, after cranking off a few lucky frames, we’re like kids walking home from confession, feeling fine and pure at first, and then remembering, “D’OH! I forgot to tell Father about the time I sassed my teacher!”

Too Catholic? (And downright boring on the sins, by the way..but, hey) Point is, there is always one more way to visualize nearly everything you care enough about to make a picture of. For one thing, we are always shooting either the cause or the effect of things. The great facial reaction and the surprise that induces it. The deep pool of rain and the portentous sky that sent it. The force that’s released in an explosion and the origin of that force. When we’re there, when the magic of whatever we came to see is happening, right here, right now, we need to think up, down, sideways for pictures of all of it, or as many as we can capture within our power….’cause once you’re home, safe and dry, it’s all different. The story perishes like a soap bubble. Shoot while you’re there. Shoot for all the story is worth.

It can be simple things. I saw the above image at one of the lesser outbuildings at Taliesin West, Frank Lloyd Wright’s legendary teaching compound in Scottsdale, Arizona. An abstract pattern made from over-hanging strips of canvas,used as makeshift shade on a path. But when I reversed my angle and shot the sidewalk instead of the sky, I saw the effect of that cause, and it appealed to me too (see left). One composition favored color, while the other seemed to dictate black & white, but they both could serve my purpose in different ways. Click and click.

It bears remembering that the only picture that is guaranteed to be a failure is the one you didn’t take. Flip things around. Re-imagine the order, the role of things. Go for one more version of what’s “important”.

Hey, you’re there anyway.…..