NOT WHAT I CAME FOR, BUT…

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ANYONE WHO’S MADE A ROAD TRIP CAN TELL YOU THAT THE DESTINATION IS OFTEN FAR LESS ENJOYABLE THAN THE JOURNEY, a truth that also applies to photography. The best things result from the little surprises at the side of the highway. You’re fixated on your oh-so-holy “plan” and all the wonderful things you’ll see and do in executing it. But photography is an art of opportunity, and to the degree that you embrace that fact, your work will be broader, richer, looser.

This is now a real source of excitement for me. I still go to the trouble of sketching out what I think I’m going to do, but, I’m at least quietly excited to know that, in many cases, the images that will make the keepers pile will happen when I went completely off message. Yes, we are “officially” here today to shoot that big mountain over yonder. But, since the two people I met on the approach path to said mountain are in themselves interesting, the story has now become about them. I may or may not get back to the mountain, and, if I do, I may discover that I really did not have a strong concept in my bagga trix for making anything special out of it, and so it’s nice not to have to write the entire day off to a good walk spoiled.

Specific example: I have written before that I get more usable stuff in the empty spaces and non-exhibit areas of museums than I do from the events within them. This is a great consolation prize these days, especially since an increasingly ardent police state among curators means that no photos can be taken in some pretty key areas. Staying open means that I can at least extract something from the areas no one is supposed to care about.

The above image is one such case, since it was literally the final frame I shot on my way out of a museum show. It was irresistible as a pattern piece, caused by a very fleeting moment of sunset light. It would have appealed to me whether I was in a museum or not, but it was the fact that I was willing to go off-script that I got it, no special technical talent or “eye”. Nabbing this shot completely hinged on whether I was willing to go after something I didn’t originally come for. It’s like going to the grocery store for milk, finding they’re out, but discovering that there is also a sale on Bud Light. Things immediately look rosier.

Or at least they will by the third can.

SETTING THE CAPTIVES FREE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’D LIKE TO ERADICATE THE WORD “CAPTURE” FROM MOST PHOTOGRAPHIC CONVERSATIONS. It suggests something stiff or inflexible to me, as if there is only one optimum way to apprehend a moment in an image. Especially in the case of portraits, I don’t think that there can be a single way to render a face, one perfect result that says everything about a person in a scant second of recording. If I didn’t capture something, does that mean my subject “got away” in some way, eluded me, remains hidden? Far from it. I can take thirty exposures of the same face and show you thirty different people. The word has become overused to the point of meaningless.

We are all conditioned to think along certain bias lines to consider a photograph well done or poorly done, and those lines are fairly narrow. We defer to sharpness over softness. We prefer brightly lit to mysteriously dark. We favor naturalistically colored and framed recordings of subjects to interpretations that keep color and composition “codes” fluid, or even reject them outright. It takes a lot of shooting to break out of these strictures, but we need to make this escape if we are to move toward anything approaching a style of our own.

I remember being startled in 1966 when I first saw Jerry Schatzberg’s photograph of Bob Dylan on the cover of the Blonde On Blonde album. How did the editor let this shot through? It’s blurred. It’s a mistake. It doesn’t…..wait, I can’t get that face out of my head. It’s Bob Dylan right now, so right now that he couldn’t be bothered to stand still long enough for a snap. The photo really does (last time I say this) capture something fleeting about the electrical, instantaneous flow of events that Dylan is swept up in. It moves. It breathes. And it’s more significant in view of the fact that there were plenty of pin-sharp frames to choose from in that very same shoot. That means Schatzberg and Dylan picked the softer one on purpose.

There are times when one 10th of a second too slow, one stop too small, is just right for making the magic happen. This is where I would usually mention breaking a few eggs to make an omelette, but for those of you on low-cholesterol diets, let’s just say that n0 rule works all the time, and that there’s more than one way to skin (or capture) a cat.

A PLACE APART

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS USUALLY USE FACES AS THE SOLE BAROMETER OF EMOTION. It’s really easy to use a person’s features as the most obvious cues to one’s inner mind. Scowls, smiles, smirks, downcast eyes, sidelong glances,cries of anguish….these are standard tools in depicting someone as either assimilated into the mass of humanity or cast away, separate and alone.

But faces are only one way of showing people as living in a place apart. Symbolically, there is an equally dramatic effect to be achieved by the simple re-contextualizing of that person in space. The arrangement of space near your subject forces the viewer to conclude that he or she is either in harmony with their surroundings or lonely, solitary, sad even, and you do it without showing so much as a raised eyebrow. This is where composition isn’t just a part of the story, but the story itself.

The woman shown here is most likely just walking from point A to point B, with no undercurrent of real tragedy. But once she takes a short cut down an alley, she can be part of a completely different, even imaginary story. Here the two walls isolate her, herding her into a context where she could be lonely, sad, afraid, furtive. She is walking away from us, and that implies a secret. She is “withdrawing” and that implies defeat. She is without a companion, which can symbolize punishment, banishment, exile. From us? From herself? From the world? Once you start to think openly about it, you realize that placing the subject in space lays the foundation for storytelling, a technique that is easy to create, recalibrate, manipulate.

The space around people is a key player in the drama an image can generate. It can mean, well, whatever you need it to mean. People who exist in a place apart become the centerpieces in strong photographs, and the variability of that strength is in your hands.

THE ENVELOPE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

HAVING LIVED IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST FOR OVER FIFTEEN YEARS, I HAVE NEGOTIATED MY OWN TERMS WITH THE BLAZING OVERKILL OF MIDDAY SUNLIGHT, and its resulting impact on photography. If you move to Arizona or New Mexico from calmer climates, you will find yourself quickly constricting into a severe squint from late breakfast to early evening, with your camera likewise shrinking from the sheer overabundance of harsh, white light. If you’re determined to shoot in midday, you will adjust your approach to just about everything in your exposure regimen.

Good news, however: if you prefer to shoot in the so-called “golden hour” just ahead of sunset, you will be rewarded with some of the most picturesque tones you’ve ever had the good luck to work with. As has been exhaustively explained by better minds than mine, sunlight lingers longer in the atmosphere during the pre-sunset period, which, in the southwest, can really last closer to two hours or more. Hues are saturated, warm: shadows are powerful and sharp. And, if that dramatic contrast works to your advantage in color, it really packs a punch in monochrome.

This time of day is what I call “the envelope”, which is to say that objects look completely different in this special light from how they register in any other part of the day, if you can make up your mind as to what to do in a hurry. Changes from minute to minute are fast and stark in their variance. Miss your moment, and you must wait another 24 hours for a re-do.

In the west, the best action actually happens after High Noon. Just before sunset in Scottsdale, AZ: 1/500 sec., f/4.5, ISO 100, 35mm.

The long shadow of an unseen sign visible in the above frame lasted about fifteen minutes on the day of the shoot. The sign itself is a metal cutout of a cowboy astride a bucking bronco, the symbol of Scottsdale, Arizona, “the most western town in the USA”. The shadow started as a short patch of black directly in front of the rusted bit of machine gear in the foreground, then elongated to an exaggerated duplicate of the sign, extending halfway down the block and becoming a sharper and more detailed silhouette.

A few minutes later, it grew softer and eventually dissolved as the sun crept closer to the western horizon. There would still be blazing illumination and harsh shadows for some objects, if you went about two stories high or higher, but, generally, sunset was well under way. Caught in time, the shadow became an active design element in the shot, an element strong enough to come through even in black and white.

If you are ever on holiday in the southwest, peek inside “the envelope”. There’s good stuff inside.

INS AND OUTS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN IT COMES TO DISCUSSIONS ABOUT ART, THE WORD “ABSTRACT” IS PROBABLY THE MOST BATTED-ABOUT LINGUISTIC SHUTTLECOCK OF THE 20TH CENTURY, something we lob at each other across the conversational net as it suits our mood. Whenever we feel we should weigh in on a matter of artistic heft, especially something that doesn’t fit into a conveniently familiar cubbyhole, we drag “abstract” out of the desk drawer, dust it off, and cram it into place somewhere in the argument.

Any talk of architecture, and the photographer’s reaction to it, attracts a lot of stray “abstracts”, since attaching the word seems to settle… something. However, art can never be about settling anything. In fact, it’s about churning things up, starting, rather than resolving, arguments. As pieces of pure design, finished buildings do make a statement of sorts about the architect’s view, at least. But when trolling about town, I am more drawn to incomplete or skeletal frameworks for buildings yet to be. They are simply open to greater interpretation as visual subject matter, since we haven’t, if you like, seen all the architect’s cards yet. The emerging project can, for a time, be anything, depending literally on where you stand or how light shapes the competing angles and contours.

I feel that open or unfinished spaces are really ripe with an infinite number of framings, since a single uncompleted wall gives way so openly to all the other planes and surfaces in the design, a visual diagram that will soon be closed up, sealed off, sequestered from view. And as for the light, there is no place it cannot go, so you can chase the tracking of shadows all day long, as is possible with, say, the Grand Canyon, giving the same composition drastically different flavors in just the space of a few hours.

If the word “abstract” has any meaning at all at this late date, you could say that it speaks to a variation, a reworking of the dimensions of what we consider reality. Beyond that, I need hip waders. However, I believe that emerging buildings represent an opportunity for photographers to add their own vision to the architect’s, however briefly.

Whew. Now let’s all go out get a drink.

THE UNSEEN GEOMETRY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE MANY PHOTO SITES THAT SUGGEST SHOOTS CALLED “WALKABOUTS“, informal outings intended to force photographers to shoot whatever comes to hand with as fresh an eye as possible. Some walkabouts are severe, in that they are confined to the hyper-familiar surroundings of your own local neighborhood; others are about dropping yourself into a completely random location and making images out of either the nothing of the area or the something of what you can train yourself to see.

Walks can startle you or bore you to tears (both on some days), but they will sharpen your approach to picture-making, since what you do is far more important than what you’re pointing to. And the discipline is sound: you can’t hardly miss taking shots of cute cats or July 4 fireworks, but neither will you learn very much that is new. Forcing yourself to abandon flashier or more obvious subjects teaches you to imbue anything with meaning or impact, a skill which is, over a lifetime, beyond price.

One of the things I try to keep in mind is how much of our everyday environment is designed to be “invisible”, or at least harder to see. Urban infrastructure is all around us, but its fixtures and connections tend to be what I call the unseen geometry, networks of service and connectivity to which we simply pay no attention, thus rendering them unseeable even to our photographer’s eye. And yet infrastructure has its own visual grammar, giving up patterns, even poetry when placed into a context of pure design.

The above power tower, located in a neighborhood which, trust me, is not brimming with beauty, gave me the look of an aerial superhighway, given the sheer intricacy of its connective grid. The daylight on the day I was shooting softened and prettied the rig to too great a degree, so I shot it in monochrome and applied a polarizing filter to make the tower pop a little bit from the sky behind it. A little contrast adjustment and a few experimental framing to increase the drama of the capture angle, and I was just about where I wanted to be.

I had to look up beyond eye (and street) level to recognize that something strong, even eloquent was just inches away from me. But that’s what a walkabout is for. Unseen geometry, untold stories.

HOW MUCH IS TOO MUCH?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THESE DAYS IT SEEMS TO TAKE LESS TIME TO SNAP A PHOTOGRAPH THAN IT DOES TO DECIDE WHETHER IT HAS ANY MERIT. Photography is still largely about momentary judgements, and so it stands to reason that some are more well-conceived than others. There’s a strong temptation to boast that “I meant to do that, of course” when the result is a good one, and to mount an elaborate alibi when the thing crashes and burns, but, even given that very human tendency, some pictures stubbornly linger between keeper and krap, inhabiting a nether region in which you can’t absolutely pronounce them either success or failure.

The image at left is one such. It was part of a day spent in New York’s Central Park, and for most of the shots taken on that session, I can safely determine which ones “worked”. This one, however, continues to defy a clear call either way. Depending on which day I view it, it’s either a slice-of-life capture that shows the density of urban life or a visual mess with about four layers too much glop going on. I wish there were an empirical standard for things like photographs, but…..wait, I really don’t wish that at all. I like the fact that none of us is truly certain what makes a picture resonate. If there were such a standard for excellence, photography could be reduced to a craft, like batik or knitting. But it can never be. The only “mission” for a photographer, however fuzzy, is to convey a feeling. Some viewers will feel like a circuit has been completed between themselves and the artist. But even if they don’t, the quest is worthwhile, and goes ever on.

I have played with this photo endlessly, converting it to monochrome, trying to enhance detail in selective parts of it, faking a tilt-shift focus, and I finally present it here exactly as I shot it. I am gently closer to liking it than at first, but I feel like this one will be a problem child for years to come. Maybe I’m full of farm compost and it is simply a train wreck. Maybe it’s “sincere but just misunderstood”. I’m okay either way. I can accept it for a near miss, since it becomes a reference point for trying the same thing with better success somewhere down the road.

And, if it’s actually good, well, of course, I meant to do that.

THE MOST FROM THE LEAST

Reaching a comfort zone with your equipment means fewer barriers between you and the picture you want to get. 1/80 sec., f/4.5, ISO 100, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY IS ONLY PARTLY ABOUT TAKING AND VIEWING IMAGES. Truly, one of the most instructive (and humbling) elements of becoming a photographer is listening to the recitation of other photographers’ sins, something for which the internet era is particularly well suited. The web will deliver as many confessions, sermons, warnings and Monday-morning quarterbacks as you can gobble at a sitting, and, for some reason, these tales of creative woe resonate more strongly with me than tales of success. I like to read a good “how I did it” tutorial on a great picture, but I love, love, love to read a lurid “how I totally blew it” post-mortem. Gives me hope that I’m not the only lame-o lumbering around in the darkness.

One of the richest gold fields of confession for shooters are entries about how they got seduced into buying mounds of photographic toys in the hope that the next bit of gear would be the decisive moment that insured greatness. We have all (sing it with me, brothers and sisters!) succumbed to the lure of the lens, the attachment, the bracket, the golden Willy Wonka ticket that would transform us overnight from hack to hero. It might have been the shiny logo on the Nikon. It might have been the seductive curve on the flash unit. Whatever the particular Apple to our private Eden was, we believed it belonged in our kit bags, no less than plasma in a medic’s satchel. And, all too often, it turned out to be about as valuable as water wings on a whale. He who dies with the most toys probably has perished from exhaustion from having to haul them all around from shot to shot, feeding the aftermarket’s bottom line instead of nourishing his art.

My favorite photographers have always been those who have delivered the most from the least: street poet Henri Cartier-Bresson with his simple Leica, news hound Weegee with his Speed Graphic perpetually locked to f/16 and a shutter speed of 1/200. Of course, shooters who use only essential equipment are going to appeal to my working-class bias, since peeling off the green for a treasure house of toys was never in the cards for me, anyway. If I had been the youthful ward of Bruce Wayne, perhaps I would have viewed the whole thing differently, but we are who we are.

I truly believe that the more equipment you have to master, the less possible true mastery of any one part of that mound of gizmos becomes. And as I grow gray, I seem to be trying to do even more and more with less and less. I’m not quite to the point of out-and-out minimalism, but I do proceed under the principle that the feel of the shot outranks every other technical consideration, and some dark patches or soft edges can be sacrificed if my eye’s heart was in the right place.

Of course, I haven’t checked the mail today. The new B&H catalogue might be in there, in which case, cancel my appointments for the rest of the week.

Sigh.

ON THE NOSE (AND OFF)

I had originally shot the organ loft at Columbus, Ohio’s St. Joseph Cathedral in a centered, “straight on” composition. I like this variation a little better. 1/40 sec., f/3.5, ISO 1000, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AMONG THE GROUPS INVITING FLICKR USERS TO POST PHOTOGRAPHS OF A CERTAIN THEME OR TYPE, there is a group called, “This Should Be A Postcard”, apparently composed of images that are so iconically average that they resemble mass-produced tourist views of scenic locales. The name of this group puzzles me. I mean, if you called it, “Perfectly Ordinary, Non-Offensive and Safe Pictures of Over-Visited Places”, people would write you off as a troll, but I’d at least give you points for accuracy. It’s hard to understand why any art would aspire to look like something that is almost deliberately artless.

And still, it is perceived as a compliment to one’s work to be told that it “looks just like a postcard”, and, I swear, when I hear that remark about one of my own images, my first reaction is to wipe said image from the face of the earth, since that phrase means that it is (a)average, (b) unambitious), (c) unimaginative, or (d) a mere act of “recording”. Look, here’s the famous place. It looks just like you expect it to, taken from the angle that you’re accustomed to, lit, composed and executed according to a pre-existing conception of what it’s “supposed” to be. How nice.

And how unlike anything photography is supposed to be about.

This conditioning we all have to render the “official” view of well-known subjects can only lead to mediocrity and risk aversion. After all, a postcard is tasteful, perfect, symmetrical, orderly. And eventually, dull. Thankfully, the infusion of millions of new photographers into the mainstream in recent years holds the potential cure for this bent. The young will simply not hold the same things (or ways to view them) in any particular awe, and so they won’t even want to create a postcard, or anyone else’s version of one. They will shudder at the very thought of being “on the nose”.

I rail against the postcard because, over a lifetime, I have so shamelessly aspired to it, and have only been able to let go of the fantasy after becoming disappointed with myself, then unwilling to keep recycling the same approach to subject matter even one more time. For me, it was a way of gradually growing past the really formalized methods I had as a child. And it’s not magic.Even a slight variation in approach to “big” subjects, as in the above image, can stamp at least a part of yourself onto the results, and so, it’s a good thing to get the official shot out of the way early on in a shoot, then try every other approach you can think of. Chances are, your keeper will be in one of the non-traditional approaches.

Postcards say of a location, wish you were here. Photographs, made by you personally, point to your mind and say, “consider being here.”

RESTORING THE INVISIBLE

as[e The Wyandotte Building (1897), Columbus, Ohio’s first true skyscaper, seen here in a three-exposure HDR composite.

PHOTOGRAPHY IS ONE OF THE BEST RESPONSES TO THE DIZZYING SPEED OF CONTEMPORARY EXISTENCE. It is, in fact, because of a photograph’s ability to isolate time, to force our sustained view of fleeting things, that image-making is valuable as a seeing device that counteracts the mad rush of our “real time” lives. Looking into a picture lets us deal with very specific slices of time, to slowly take the measure of things that, although part of our overall sensory experience, are rendered invisible in the blur of our living.

I find that, once a compelling picture has been made of something that is familiar but unnoticed, the ability to see the design and detail of life is restored in the viewing of that thing. Frequently, in making an image of something that we are too busy to notice, the thing takes on a startlingly new aspect. That’s why I so doggedly pursue architectural subjects, in the effort to make us regard how much of our motives and ideals are captured in buildings. They stand as x-rays into our minds, revealing not only what we wanted in creating them, but what we actually created as they were realized.

In writing a book, several years ago, about a prominent midwestern skyscraper*, I was struck by how very personal these objects were…to the magnates who commissioned them, to the architects who brought them forth, and to the people in their native cities who took a kind of ownership of them. In short, the best of them were anything but mere objects of stone and steel. They imparted a personality to their surroundings.

The building pictured here, Columbus, Ohio’s 1897 Wyandotte Building, was designed by Daniel Burnham, the genius architect who spearheaded the birth of the modern steel skeleton skyscraper, heading up Chicago’s “new school” of architecture and overseeing the creation of the famous “White City” exposition of 1893. It is a magnificent montage of his ideals and vision for a burgeoning new kind of American city. As something thousand walk past every day, it is rendered strangely “invisible”, but a photograph can compensate for our haste, allowing us the luxury of contemplation.

As photographers, we can bring a particularly keen kind of witnessing to the buildings that make up our environment, no less than if we were to document the carvings and decorative design on an Egyptian sarcophagus. Architectural photography can help us extract the magic, the aims of a society, and experimenting with various methods for rendering their texture and impact can lead to some of the most powerful imagery created within a camera.

*Leveque: The First Complete Story Of Columbus’ Greatest Skyscraper, Michael A. Perkins, 2004. Available in standard print and Kindle editions through Amazon and other online bookstores.

SYMBOLS (For Father’s Day, 2014)

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY IS, ALTERNATIVELY, AN ART OF BOTH DOCUMENTATION AND SUGGESTION. It is, of course, one of its essential tasks to record, to mark events, comings, goings, arrivals, and passings. That’s basically a reporter’s function, and one which photographers have served since we first learned to trap light in a box. The other, and arguably more artistic task, is to symbolize, to show all without showing everything. And on this Father’s Day (as on every one), we honor our parents by taking photographs which address both approaches.

For many years, I have taken the obvious path by capturing the latest version of Dad’s face. It’s an ever-changing mosaic of effects, which no photographer/storyteller worth his salt can resist. But in recent years, I also am trying to symbolize my father, to make him stand not only for his own life, but for the miles traveled by all parents. For this task, a face is too specific, since it is so firmly anchored to its own specific myths and legends. To make Dad emblematic, not just as a man but rather as “Man”, I’ve found that abstracting parts of him can work a little better than a simple portrait.

These days, Dad’s hands are speaking to me with particular eloquence. They bear the marks of every struggle and triumph of human endeavor, and their increasing fragility, the etchings on the frail envelope of mortality, are especially poignant to me as I enter my own autumn. I have long since passed the point where I seem to have his hands grafted onto the ends of my own arms, so that, as I make images of him, I am doing a bit of a trending chart on myself as well. In a way, it’s like taking a selfie without actually being in front of the camera.

Hands are the human instruments of deeds, change, endeavor, strength, striving. Surviving. They are the archaeological road map of all one’s choices, all our grand crusades, all our heartbreaking failures and miscalculations. Hands tell the truth.

Dad has a great face, a marvelous mix of strength and compassion, but his hands…..they are human history writ large.

Happy Father’s Day, Boss.

FIGHTING TO FORGET

By MICHAEL PERKINS

STORIES OF “THE LAND THAT TIME FORGOT” COMPRISE ONE OF THE MOST RELIABLE TROPES IN ALL OF FICTION. The romantic notion of stumbling upon places that have been sequestered away from the mad forward crunch of “progress” is flat-out irresistible, since it holds out the hope that we can re-connect with things we have lost, from perspective to innocence. It moves units at the book store. It sells tickets at the box office. And it provides photographers with their most delicate treasures.

Whether our lost land is a village in some hidden valley or a hamlet within the vast prairie of middle America, we romanticize the idea that some places can be frozen in amber, protected from us and all that we create. Sadly, finding places that have been allowed to remain at the margins, that have been left alone by developers and magnates, is getting to be a greater rarity than ever before. Small towns can be wholly separate universes, sealed off from the silliness that has engulfed most of us, but just finding one which has been lucky enough to aspire to “forgotten” status is increasingly rare.

That’s why it’s so wonderful when you take the wrong road, and make the right turn.

The above stretch of sunlit houses, parallel to their tiny town’s main railroad spur, shows, in miniature, a place where order is simple but unwavering. Colors are basic. Lines are straight. This is a town where school board meetings are still held at the local Carnegie library, where the town’s single diner’s customers are on a first name basis with each other. A place where the flag is taken down and folded each night outside the courthouse. A village that wears its age like an elder’s furrowed brow with quietude, serenity.

There are plenty of malls, chain burger joints, car dealerships and business plazas within several miles of here. But they are not of here. They keep their distance and mind their manners. The freeway won’t be barreling through here anytime soon. There’s time yet.

Time for one more picture, as simple as I know how to make it.

A memento of a world fighting to forget.

FREE ATMOSPHERE

Panos are not for every kind of visual story. The best thing is, you can make them so quickly, it’s easy to see if it’s merely a gimmick effect or the perfect solution, given what you need to say.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PANORAMIC APPS FOR MOBILE CAMERAS CONSTITUTE A HUGE STEP FORWARD in convenience and simplicity in taking the kind of sweeping images that used to require keen skills either in film processing or in digital darkroom stitching. The newest versions of these apps are far from flawless, and, like any effect-laden add-on, they can become cheesy gimmicks, or, used to excess, merely boring. That said, there is a time and place for everything.

99% of the impact in a pano comes from the selection of your subject. Supposing a panoramic view to be a specialized way to tell a story, is the story you’re attempting to tell interesting in its own right? Does it benefit from the wider frame? Let’s recall that, as well as including a ton of extra left-and-right information, handheld pano apps create a distorted version of reality. In the earliest days of panoramas, multiple photos of a scene were taken side-by-side, all with the same distance from camera to subject. This was usually accomplished by shooting on a tripod, which was moved and measured with each new portion of what would eventually be a wide composite. At each exposure, the distance of the tripod to, say, the mountain range was essentially constant across the various exposures, rendering the wide picture all in the same plane….an optically accurate representation of the scene.

With handheld panos done in-camera, the shooter and his camera must usually pivot in a large half-circle, just as you might execute a video pan,so that some objects are closer to the lens than others, usually near the center. This guarantees a huge amount of dramatic distortion in at least one part of the image, and frequently more than one. The effect is that you are not just recording a straight left-to-right scene, but creating artificial stretches and warps of everything in your shot. You are not recording a scene that unfolds across a straight left-right horizon, but capturing things that actually encircle you and trying to “flatten them out” so they appear to occur in one unbroken line. By showing objects that may be beside or behind you, you’re kinda making a distortion of an illusion. Huh?

Again, if this is the look you want, that is, if your subject is truly served by this fantasy effect, than click away. You’ll know in a minute if it all made sense, anyhow, and that alone is a remarkable luxury. These days, we can not only get to “yes” faster, we can, more importantly, get rid of all the “no’s” in an instant as well.

EYES WITHOUT A FACE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CHILDREN ARE THE GREATEST DISPLAY SPACES FOR HUMAN EMOTION, if only because they have neither the art nor the inclination to conceal. It isn’t that they are more “honest” than adults are: it’s more like they simply have no experience hiding behind the masks that their elders use with such skill. Since photographs have to be composed within a fixed space or frame, our images are alternatively about revelation and concealment. We choose how much to show, whether to discover or hoard. That means that sometimes we tell stories like adults, and sometimes we tell them like children.

The big temptation with pictures of children is to concentrate solely on their faces, but this default actually narrows our array of storytelling tools. Yes, the eyes are the window to the soul and so forth….but a child is eloquent with everything in his physical makeup. His face is certainly the big, obvious, electric glowing billboard of his feelings, but he speaks in anything he touches, anywhere he runs toward, even the shadows he casts upon the wall. Making pictures of these fragments can produce telling statements about the state of being a child, highlighting the most poignant, and, for us, the most forgotten bits.

Children are all about unrealized potential. Since nothing’s happened yet, everything is possible. Potential and possibility are twin mysteries, and are the common language of kids. Tapping into either one can provide the best element in all of photography, and that is the element of surprise.

THE LITTLE WALLS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

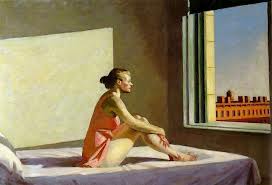

THE PAINTER EDWARD HOPPER, ONE OF THE GREATEST CHRONICLERS OF THE ALIENATION OF MAN FROM HIS ENVIRONMENT, would have made an amazing street photographer. That he captured the essential loneliness of modern life with invented or arranged scenes makes his pictures no less real than if he had happened upon them naturally, armed with a camera. In fact, his work has been a stronger influence on my approach to making images of people than many actual photographers.

“Maybe I am not very human”, Hopper remarked, “what I wanted to do was to paint sunlight on the side of a house.” Indeed, many of his canvasses fairly glow with eerily golden colors, but, meanwhile, the interiors within which his actors reside could be defined by deep shadows, stark furnishings, and lost individuals who gaze out of windows at….what? The cities in his paintings are wide open, but his subjects invariably seem like prisoners. They are sealed in, sequestered away from each other, locked by little walls apart from every other little wall.

I occasionally see arrangements of people that suggest Hopper’s world to me. Recently, I was spending the day at an art museum which features a large food court. The area is open, breathable, inviting, and nothing like the group of people in the above image. For some reason, in this place, at this moment, this distinct group of people appear as a complete universe unto themselves, separate from the whole rest of humanity, related to each other not because they know each other but because they are such absolute strangers to each other, and maybe to themselves. I don’t understand why their world drew my eye. I only knew that I could not resist making a picture of this world, and I hoped I could transmit something of what I was seeing and feeling.

I don’t know if I got there, but it was a journey worth taking. I started out, like Hopper, merely chasing the light, but lingered, to try to articulate something very different.

Or as Hopper himself said, “It you could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint”.

BRING BACK THE SHOE BOX?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS WITH MOST REVOLUTIONS, THE FAIRLY RECENT ROCKET RIDE INTO THE DIGITAL DOMAIN has created a few casualties. There simply is no way to completely transform the very act of photography without also unleashing ripples into how we view and value the images we’ve created. One of the most frequently lamented losses along these lines has to do with holding a “hard copy” picture in your hand, of having a defined physical space in which they can be easily catalogued and viewed by all. In speaking with various people about this, I sense a real emotional disconnect, a pang that can’t be satisfied by knowing that the pictures are “somewhere out there” in cyberspace. We tossed away the old family photo shoe box in all its chaos, but a key human experience was also sacrificed along the way.

If you never take the time to review the thousands of images you shoot, you lose the joy of the occasional jewels and the lessons of the near misses.

One of the consequences of the end of film is the complete banishment of numerical barriers that used to keep our photographic output at a more controllable size. A roll of film held you to 24, maybe 36 exposures. You had to budget your shots. There were no instant do-overs, no chance to shoot bursts of 60 shots of Bobby kicking the soccer ball. Now we have an overabundance of choices in shooting, which, ironically, can be a little intimidating. We can produce so many thousands of pictures in a given year that our senses simply become overwhelmed with the task of sorting, editing, or prioritizing them. Gazillions of photos go into the cloud, many unseen past the first day they are uploaded. Our ability to organize our images in any comprehensible way has not kept pace with the technology used to capture them.

I truly feel that we have to work harder than ever, not on the taking of pictures, which has become nearly intuitive in its technical ease, but on the curating of what we’ve produced. For every five hours we spend shooting, I feel that fully half that time should be spent on the careful review of everything we’ve shot, not merely the quick “like/don’t like” card shuffle many of us perform when zipping through a large batch of captures. And this is not just for we ourselves. Think about it: how can our families and friends think of our photography as a visual legacy in the way we once regarded that shoe box if they have no real appreciation of what all is even in the new, virtual equivalent of that box? If it takes us months after we do a shoot to have even a rough idea of what resulted, we are missing the occasional jewel as well as the instructive power of the many near misses. That’s having an experience without availing yourself of any idea of what it meant, and that is crazy.

There is a reason that McDonald’s only offers Coke in three serving sizes. As consumers, we really crash into paralysis when presented with too many choices. We think we want a selection consisting of, well, everything, but we seldom make use of such overwhelming sensory input. I’m a huge fan of being able to shoot as many images as you need to get what will become your precious few “keepers”. But trying to keep everything without separating the wheat from the chaff isn’t art. It isn’t even collecting.

It’s just hoarding.

THE MAIN POINT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MAKING PICTURES, FOR ME, IS LIKE MAKING TAFFY. The only good results I get are from stretching and twisting between two extremes. Push and pull. Yank and compress. Stray and stay. Say everything or speak one single word.

This is all about composition, the editing function of what to put in or leave out. In my head, it’s a constant and perpetually churning debate over what finally resides within the frame. No, that needs something more. No, that’s way too much. Cut it. Add it. I love it, it’s complete chaos. I love it, it’s stark and lonely.

Can’t settle the matter, and maybe that’s the point. How can your eye always do the same kind of seeing? How can your heart or mind ever be satisfied with one type of poem or story? Just can’t, that’s all.

But I do have a kind of mental default setting I return to, to keep my tiny little squirrel brain from exploding.

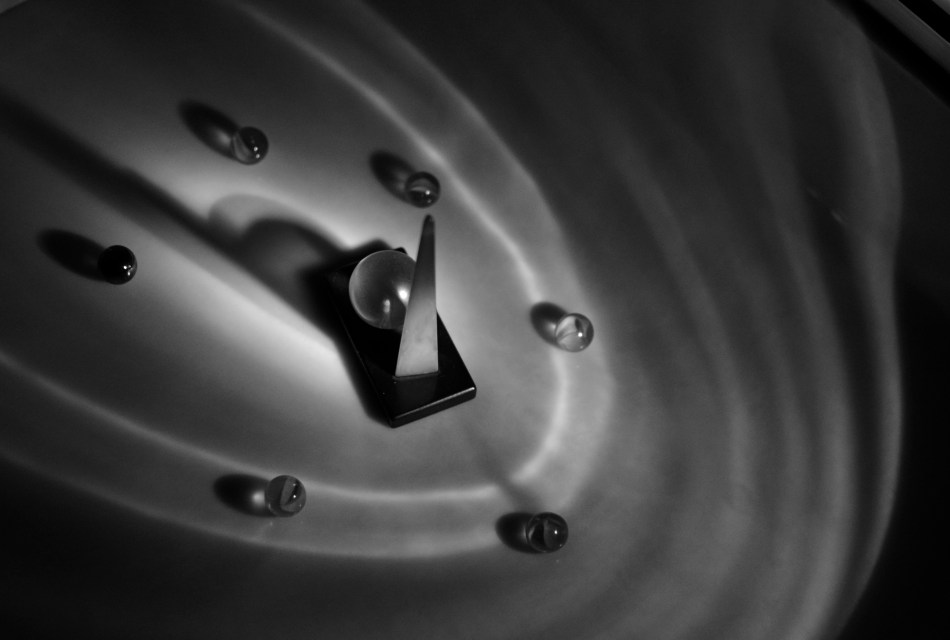

When I need to clean out the pipes, I tend to gravitate to the simplest compositions imaginable, a back-to-basics approach that forces me to see things with the fewest possible elements, then to begin layering little extras back in, hoping I’ll know when to stop. In the case of the above image, I was shooting inside a darkened room with only an old 1939 World’s Fair paperweight for a subject, and holding an ordinary cheap flashlight overhead with one hand as I framed and focused, handheld, with the other hand. I didn’t know what I wanted. It was a fishing expedition, plain and simple. What I soon decided, however, was that, instead of one element, I was actually working with two.

Basic flashlights have no diffusers, and so they project harsh concentric circles as a pattern. Shifting the position of the flashlight seemed to make the paperweight appear to be ringed by eddying waves, orbit trails if you will. Suddenly the mission had changed. I now had something I could use as the center of a little solar system, so, now,for a third element, I needed “satellites” for that realm. Back to the junk drawer for a few cat’s eye marbles. What, you don’t have a bag of marbles in the same drawer with your shaving razor and toothpaste? What kinda weirdo are you?

Shifting the position of the marbles to suggest eccentric orbits, and tilting the light to create the most dramatic shadow ellipses possible gave me what I was looking for….a strange, dreamlike little tabletop galaxy. Snap and done.

Sometimes going back to a place where there are no destinations and no rules help me refocus my eye. Or provides me with the delusion that I’m in charge of some kind of process.

THE ENNOBLING GOLD

Brooklyn Block, 2014. No, this building isn’t this pretty in “reality”. And that’s the entire point. 1/100 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LIGHT IS THE ULTIMATE MAKE-UP ARTIST, the cosmetic balm that paints warmth, softness, even a kind of forgiveness, or dignity onto the world. Photographers use light in a different way than painters, since a canvas, beginning as a complete blank, allows the dauber to create any kind of light scheme he desires. It’s a very God-like, “let there be light” position the painter finds himself in, whereas the photographer is more or less at light’s mercy, if you will. He has to channel, harness, or manage whatever the situation has provided him with, to wrangle light into an acceptable balance.

No complaints about this, by the way. There’s nothing passive about this process: real decisions are being made, and both painters and photographers are judged by how they temper and combine all the elements they use in their assembly processes. Just because a shooter works with light as he finds it, rather than brushing it into being, doesn’t make him/her any less in charge of the result. It’s just a different way to get there.

Light always has the power to transform objects into, if you will, better versions of themselves. I call it the “ennobling gold”, since I find that the yellow range of light is kindest to a wider range of subjects. Stone or brick, urban crush or rural hush, light produces a calming, charming effect on nearly anything, which is what makes managing light so irresistible to the photographer. He just knows that there is beauty to be extracted when the light is kind. And he can’t wait to grab all he can.

“Light makes photography”, George Eastman famously wrote. “Light makes photography. Embrace light. Admire it. Love it. But, above all, know light. Know it for all you are worth, and you will know the key to photography.”

Yeah, what he said.

THE RIGHT WAGON

Cheap fisheye adaptors are a mixed bag optically, but they can convey a mood. 1/40 sec., f/11, ISO 100, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I ONCE HEARD AN OLD PHOTOGRAPHER SPEAK OF CREATIVE CHOICES AS “picking the right wagon to haul your goods to market”. By that, he meant that format, film, frame size, lens type or aperture were all just means to an end. If one wouldn’t take your wagon all the way to a finished picture, use another. He had no special sentiment or ironclad loyalty to any one tool, since there was, and is, only one real goal in any of photography: get the image you came to get.

It’s often hard to remember that simple rule, since we tend to associate the success of certain pictures with our pet camera, our sweet spot aperture, our favorite hunk of glass. But there’s also a knack to knowing when a particular tool that is wrong, wrong, wrong for almost anything might, for the project at hand, be just perfect.

I have one such tool, and, on rare occasions, the very properties that make me generally curse it as a cheap chunk of junk can make me praise it as just what the doctor ordered. It’s an Opteka 0.35, a screw-on lens adapter that simulates (to put it kindly) at least the dimensions of a true fisheye, without the enormous layout of dough, or, sadly, the optical precision of a true dedicated lens. It’s fuzzy at the edges, regardless of your aperture. It sprays chromatic shmears all over those edges, and so you can’t even dream of sharpness beyond the third of the image that’s in the dead center of the lens. It was, let’s be honest, a cheap toy bought by a cheap photographer (me) as a shortcut. For 99% of any ulta-wide imaging, it’s akin to taking a picture through a jellyfish bladder.

But.

Since the very essence of fisheye photography is as a distortion of reality, the Opteka can be a helping hand toward a fantasy look. Overall sharpness in a fisheye shot can certainly be a desired effect, but, given your subject matter, it need not be a deal breaker.

In the case of some recent monochrome studies of trees I’ve been undertaking, for example, the slightly supernatural effect I’m after isn’t dependent on a “real” look, and running the Opteka in black and white with a little detail boost on the back end gives me the unreal appearance that is right for what I want to convey about the elusive, even magical elements of trees. The attachment is all kinds of wrong for most other kinds of images, but, again, the idea is to get the feel you’re looking for…in that composition, on that day, under those circumstances.

I’ve love to get to the day when one lens will do everything in all instances, but I won’t live that long, and, chances are, neither will you. Meanwhile, I gotta get my goods to market, and for the slightly daft look of magickal trees, the Opteka is my Leica.

For now.

STUPIDLY WISE

Blendon Woods, Columbus, Ohio, 1966. I usually had to shoot an entire roll of film to even come this close to making a useable shot.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IGNORANCE, IN PHOTOGRAPHY, CERTAINLY IS NOT BLISS. However, exposure to that selfsame know-nothing-ness can lead to a kind of bliss, since it can eventually lead you to excellence, or at least improvement. Here and now, I am going to tell you that all the photographic tutorials and classes in history cannot teach you one millionth as much as your own rotten pictures. Period.

Trick is, you have to keep your misbegotten photographic children, and keep them close. Love them. Treasure the hidden reservoir of warnings and no-nos they contain and mine that treasure for all it’s worth. Of course, doing this takes real courage, since your first human instinct, understandingly, will be to do a Norman Bates on them: stab them to death in the shower and bury their car in the swamp out back.

But don’t.

I have purposely kept the results of the first five rolls of film I ever shot for over forty years now. They are almost all miserable failures, and I mean that with no aw-shucks false modesty whatever. I am not exaggerating when I tell you that these images are the Fort Knox of ignorance, an ignorance taller than most minor mountain ranges, an ignorance that, if it was used like some garbage to create energy, could light Europe for a year. We’re talking lousy.

But mine was a divine kind of ignorance. At the age of fourteen, I not only knew nothing, I could not even guess at how much nothing I knew. It’s obvious, as you troll through these Kodak-yellow boxes of Ektachrome slides, that I knew nothing of the limits of film, or exposure, or my own cave-dweller-level camera. Indeed, I remember being completely mystified when I got my first look at my slides as they returned from the processor (an agonizing wait of about three days back then), only to find, time after time, that nothing of what I had seen in my mind had made it into the final image. It wasn’t that dark! It wasn’t that color! It wasn’t…..working. And it wasn’t a question of, “what was I thinking?”, since I always had a clear vision of what I thought the picture should be. It was more like, “why didn’t that work?“, which, at that stage of my development, was as easy to answer as, say, “why don’t I have a Batmobile?” or “why can’t I make food out of peat moss?”

Different woods, different life. But you can’t get here without all the mistakes it builds on. 1/400 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

But holding onto the slides over the years paid off. I gradually learned enough to match up Lousy Slide “A” with Solution”B”, as I learned what to ask of myself and a camera, how to make the box do my bidding, how to build on the foundation of all that failure. And the best thing about keeping all of the fizzles in those old cartons was that I also kept the few slides that actually worked, in spite of a fixed-focus, plastic lens, light-leaky box camera and my own glorious stupidity. Because, since I didn’t know what I could do, I tried everything, and, on a few miraculous occasions, I either guessed right, or God was celebrating Throw A Mortal A Bone Day.

Thing is, I was reaching beyond what I knew, what I could hope to accomplish. Out of that sheer zeal, you can eventually learn to make photographs. But you have to keep growing beyond your cameras. It’s easy when it’s a plastic hunk of garbage, not so easy later on. But you have to keep calling on that nervy, ignorant fourteen-year-old, and giving him the steering wheel. It’s the only way things get better.

You can’t learn from your mistakes until you room with them for a semester or two. And then they can teach you better than anyone or anything you will ever encounter, anywhere.