HOW MUCH IS TOO MUCH?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THESE DAYS IT SEEMS TO TAKE LESS TIME TO SNAP A PHOTOGRAPH THAN IT DOES TO DECIDE WHETHER IT HAS ANY MERIT. Photography is still largely about momentary judgements, and so it stands to reason that some are more well-conceived than others. There’s a strong temptation to boast that “I meant to do that, of course” when the result is a good one, and to mount an elaborate alibi when the thing crashes and burns, but, even given that very human tendency, some pictures stubbornly linger between keeper and krap, inhabiting a nether region in which you can’t absolutely pronounce them either success or failure.

The image at left is one such. It was part of a day spent in New York’s Central Park, and for most of the shots taken on that session, I can safely determine which ones “worked”. This one, however, continues to defy a clear call either way. Depending on which day I view it, it’s either a slice-of-life capture that shows the density of urban life or a visual mess with about four layers too much glop going on. I wish there were an empirical standard for things like photographs, but…..wait, I really don’t wish that at all. I like the fact that none of us is truly certain what makes a picture resonate. If there were such a standard for excellence, photography could be reduced to a craft, like batik or knitting. But it can never be. The only “mission” for a photographer, however fuzzy, is to convey a feeling. Some viewers will feel like a circuit has been completed between themselves and the artist. But even if they don’t, the quest is worthwhile, and goes ever on.

I have played with this photo endlessly, converting it to monochrome, trying to enhance detail in selective parts of it, faking a tilt-shift focus, and I finally present it here exactly as I shot it. I am gently closer to liking it than at first, but I feel like this one will be a problem child for years to come. Maybe I’m full of farm compost and it is simply a train wreck. Maybe it’s “sincere but just misunderstood”. I’m okay either way. I can accept it for a near miss, since it becomes a reference point for trying the same thing with better success somewhere down the road.

And, if it’s actually good, well, of course, I meant to do that.

THE MOST FROM THE LEAST

Reaching a comfort zone with your equipment means fewer barriers between you and the picture you want to get. 1/80 sec., f/4.5, ISO 100, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY IS ONLY PARTLY ABOUT TAKING AND VIEWING IMAGES. Truly, one of the most instructive (and humbling) elements of becoming a photographer is listening to the recitation of other photographers’ sins, something for which the internet era is particularly well suited. The web will deliver as many confessions, sermons, warnings and Monday-morning quarterbacks as you can gobble at a sitting, and, for some reason, these tales of creative woe resonate more strongly with me than tales of success. I like to read a good “how I did it” tutorial on a great picture, but I love, love, love to read a lurid “how I totally blew it” post-mortem. Gives me hope that I’m not the only lame-o lumbering around in the darkness.

One of the richest gold fields of confession for shooters are entries about how they got seduced into buying mounds of photographic toys in the hope that the next bit of gear would be the decisive moment that insured greatness. We have all (sing it with me, brothers and sisters!) succumbed to the lure of the lens, the attachment, the bracket, the golden Willy Wonka ticket that would transform us overnight from hack to hero. It might have been the shiny logo on the Nikon. It might have been the seductive curve on the flash unit. Whatever the particular Apple to our private Eden was, we believed it belonged in our kit bags, no less than plasma in a medic’s satchel. And, all too often, it turned out to be about as valuable as water wings on a whale. He who dies with the most toys probably has perished from exhaustion from having to haul them all around from shot to shot, feeding the aftermarket’s bottom line instead of nourishing his art.

My favorite photographers have always been those who have delivered the most from the least: street poet Henri Cartier-Bresson with his simple Leica, news hound Weegee with his Speed Graphic perpetually locked to f/16 and a shutter speed of 1/200. Of course, shooters who use only essential equipment are going to appeal to my working-class bias, since peeling off the green for a treasure house of toys was never in the cards for me, anyway. If I had been the youthful ward of Bruce Wayne, perhaps I would have viewed the whole thing differently, but we are who we are.

I truly believe that the more equipment you have to master, the less possible true mastery of any one part of that mound of gizmos becomes. And as I grow gray, I seem to be trying to do even more and more with less and less. I’m not quite to the point of out-and-out minimalism, but I do proceed under the principle that the feel of the shot outranks every other technical consideration, and some dark patches or soft edges can be sacrificed if my eye’s heart was in the right place.

Of course, I haven’t checked the mail today. The new B&H catalogue might be in there, in which case, cancel my appointments for the rest of the week.

Sigh.

FIGHTING TO FORGET

By MICHAEL PERKINS

STORIES OF “THE LAND THAT TIME FORGOT” COMPRISE ONE OF THE MOST RELIABLE TROPES IN ALL OF FICTION. The romantic notion of stumbling upon places that have been sequestered away from the mad forward crunch of “progress” is flat-out irresistible, since it holds out the hope that we can re-connect with things we have lost, from perspective to innocence. It moves units at the book store. It sells tickets at the box office. And it provides photographers with their most delicate treasures.

Whether our lost land is a village in some hidden valley or a hamlet within the vast prairie of middle America, we romanticize the idea that some places can be frozen in amber, protected from us and all that we create. Sadly, finding places that have been allowed to remain at the margins, that have been left alone by developers and magnates, is getting to be a greater rarity than ever before. Small towns can be wholly separate universes, sealed off from the silliness that has engulfed most of us, but just finding one which has been lucky enough to aspire to “forgotten” status is increasingly rare.

That’s why it’s so wonderful when you take the wrong road, and make the right turn.

The above stretch of sunlit houses, parallel to their tiny town’s main railroad spur, shows, in miniature, a place where order is simple but unwavering. Colors are basic. Lines are straight. This is a town where school board meetings are still held at the local Carnegie library, where the town’s single diner’s customers are on a first name basis with each other. A place where the flag is taken down and folded each night outside the courthouse. A village that wears its age like an elder’s furrowed brow with quietude, serenity.

There are plenty of malls, chain burger joints, car dealerships and business plazas within several miles of here. But they are not of here. They keep their distance and mind their manners. The freeway won’t be barreling through here anytime soon. There’s time yet.

Time for one more picture, as simple as I know how to make it.

A memento of a world fighting to forget.

FREE ATMOSPHERE

Panos are not for every kind of visual story. The best thing is, you can make them so quickly, it’s easy to see if it’s merely a gimmick effect or the perfect solution, given what you need to say.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PANORAMIC APPS FOR MOBILE CAMERAS CONSTITUTE A HUGE STEP FORWARD in convenience and simplicity in taking the kind of sweeping images that used to require keen skills either in film processing or in digital darkroom stitching. The newest versions of these apps are far from flawless, and, like any effect-laden add-on, they can become cheesy gimmicks, or, used to excess, merely boring. That said, there is a time and place for everything.

99% of the impact in a pano comes from the selection of your subject. Supposing a panoramic view to be a specialized way to tell a story, is the story you’re attempting to tell interesting in its own right? Does it benefit from the wider frame? Let’s recall that, as well as including a ton of extra left-and-right information, handheld pano apps create a distorted version of reality. In the earliest days of panoramas, multiple photos of a scene were taken side-by-side, all with the same distance from camera to subject. This was usually accomplished by shooting on a tripod, which was moved and measured with each new portion of what would eventually be a wide composite. At each exposure, the distance of the tripod to, say, the mountain range was essentially constant across the various exposures, rendering the wide picture all in the same plane….an optically accurate representation of the scene.

With handheld panos done in-camera, the shooter and his camera must usually pivot in a large half-circle, just as you might execute a video pan,so that some objects are closer to the lens than others, usually near the center. This guarantees a huge amount of dramatic distortion in at least one part of the image, and frequently more than one. The effect is that you are not just recording a straight left-to-right scene, but creating artificial stretches and warps of everything in your shot. You are not recording a scene that unfolds across a straight left-right horizon, but capturing things that actually encircle you and trying to “flatten them out” so they appear to occur in one unbroken line. By showing objects that may be beside or behind you, you’re kinda making a distortion of an illusion. Huh?

Again, if this is the look you want, that is, if your subject is truly served by this fantasy effect, than click away. You’ll know in a minute if it all made sense, anyhow, and that alone is a remarkable luxury. These days, we can not only get to “yes” faster, we can, more importantly, get rid of all the “no’s” in an instant as well.

EYES WITHOUT A FACE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CHILDREN ARE THE GREATEST DISPLAY SPACES FOR HUMAN EMOTION, if only because they have neither the art nor the inclination to conceal. It isn’t that they are more “honest” than adults are: it’s more like they simply have no experience hiding behind the masks that their elders use with such skill. Since photographs have to be composed within a fixed space or frame, our images are alternatively about revelation and concealment. We choose how much to show, whether to discover or hoard. That means that sometimes we tell stories like adults, and sometimes we tell them like children.

The big temptation with pictures of children is to concentrate solely on their faces, but this default actually narrows our array of storytelling tools. Yes, the eyes are the window to the soul and so forth….but a child is eloquent with everything in his physical makeup. His face is certainly the big, obvious, electric glowing billboard of his feelings, but he speaks in anything he touches, anywhere he runs toward, even the shadows he casts upon the wall. Making pictures of these fragments can produce telling statements about the state of being a child, highlighting the most poignant, and, for us, the most forgotten bits.

Children are all about unrealized potential. Since nothing’s happened yet, everything is possible. Potential and possibility are twin mysteries, and are the common language of kids. Tapping into either one can provide the best element in all of photography, and that is the element of surprise.

THE LITTLE WALLS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

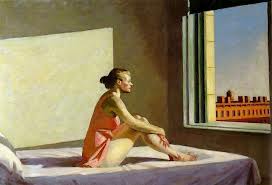

THE PAINTER EDWARD HOPPER, ONE OF THE GREATEST CHRONICLERS OF THE ALIENATION OF MAN FROM HIS ENVIRONMENT, would have made an amazing street photographer. That he captured the essential loneliness of modern life with invented or arranged scenes makes his pictures no less real than if he had happened upon them naturally, armed with a camera. In fact, his work has been a stronger influence on my approach to making images of people than many actual photographers.

“Maybe I am not very human”, Hopper remarked, “what I wanted to do was to paint sunlight on the side of a house.” Indeed, many of his canvasses fairly glow with eerily golden colors, but, meanwhile, the interiors within which his actors reside could be defined by deep shadows, stark furnishings, and lost individuals who gaze out of windows at….what? The cities in his paintings are wide open, but his subjects invariably seem like prisoners. They are sealed in, sequestered away from each other, locked by little walls apart from every other little wall.

I occasionally see arrangements of people that suggest Hopper’s world to me. Recently, I was spending the day at an art museum which features a large food court. The area is open, breathable, inviting, and nothing like the group of people in the above image. For some reason, in this place, at this moment, this distinct group of people appear as a complete universe unto themselves, separate from the whole rest of humanity, related to each other not because they know each other but because they are such absolute strangers to each other, and maybe to themselves. I don’t understand why their world drew my eye. I only knew that I could not resist making a picture of this world, and I hoped I could transmit something of what I was seeing and feeling.

I don’t know if I got there, but it was a journey worth taking. I started out, like Hopper, merely chasing the light, but lingered, to try to articulate something very different.

Or as Hopper himself said, “It you could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint”.

BRING BACK THE SHOE BOX?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS WITH MOST REVOLUTIONS, THE FAIRLY RECENT ROCKET RIDE INTO THE DIGITAL DOMAIN has created a few casualties. There simply is no way to completely transform the very act of photography without also unleashing ripples into how we view and value the images we’ve created. One of the most frequently lamented losses along these lines has to do with holding a “hard copy” picture in your hand, of having a defined physical space in which they can be easily catalogued and viewed by all. In speaking with various people about this, I sense a real emotional disconnect, a pang that can’t be satisfied by knowing that the pictures are “somewhere out there” in cyberspace. We tossed away the old family photo shoe box in all its chaos, but a key human experience was also sacrificed along the way.

If you never take the time to review the thousands of images you shoot, you lose the joy of the occasional jewels and the lessons of the near misses.

One of the consequences of the end of film is the complete banishment of numerical barriers that used to keep our photographic output at a more controllable size. A roll of film held you to 24, maybe 36 exposures. You had to budget your shots. There were no instant do-overs, no chance to shoot bursts of 60 shots of Bobby kicking the soccer ball. Now we have an overabundance of choices in shooting, which, ironically, can be a little intimidating. We can produce so many thousands of pictures in a given year that our senses simply become overwhelmed with the task of sorting, editing, or prioritizing them. Gazillions of photos go into the cloud, many unseen past the first day they are uploaded. Our ability to organize our images in any comprehensible way has not kept pace with the technology used to capture them.

I truly feel that we have to work harder than ever, not on the taking of pictures, which has become nearly intuitive in its technical ease, but on the curating of what we’ve produced. For every five hours we spend shooting, I feel that fully half that time should be spent on the careful review of everything we’ve shot, not merely the quick “like/don’t like” card shuffle many of us perform when zipping through a large batch of captures. And this is not just for we ourselves. Think about it: how can our families and friends think of our photography as a visual legacy in the way we once regarded that shoe box if they have no real appreciation of what all is even in the new, virtual equivalent of that box? If it takes us months after we do a shoot to have even a rough idea of what resulted, we are missing the occasional jewel as well as the instructive power of the many near misses. That’s having an experience without availing yourself of any idea of what it meant, and that is crazy.

There is a reason that McDonald’s only offers Coke in three serving sizes. As consumers, we really crash into paralysis when presented with too many choices. We think we want a selection consisting of, well, everything, but we seldom make use of such overwhelming sensory input. I’m a huge fan of being able to shoot as many images as you need to get what will become your precious few “keepers”. But trying to keep everything without separating the wheat from the chaff isn’t art. It isn’t even collecting.

It’s just hoarding.

THE FULLNESS OF EMPTY

By MICHAEL PERKINS SCIENCE TELLS US THAT SOME HUSBANDS HEAR THE QUESTION, “DID YOU TAKE THE TRASH OUT?” more often than any other phrase over the course of their married life. If you are an intrepid road warrior, you may hear more of something like “do you know where you’re going?” or “why don’t you just stop and ask for directions?”. If you’re a less than optimum companion, the most frequently heard statement might be along the lines of “and just where have you been?”. For me, at least when I have a camera in my hands, it’s always been “why don’t you ever take pictures of people?”

Why, indeed.

Of course, I contend that, if you were to take a random sample of any 100 of my photographs, there would be a fair representation of the human animal within that swatch of work. Not 85% percent, certainly, but you wouldn’t think you were watching snapshots from I Am Legend. However, I can’t deny that I have always seen stories in empty spaces or building faces, stories that may or may not resonate with everyone. It’s a definite bias, but it’s one of the closest things to a style or a vision that I have.

I think that absent people, as measured in their after-echoes in the places where they have been, speak quite clearly, and I am not alone in this view. Putting a person that I don’t even know into an image, just to demonstrate scope or scale, can be, to me, more dehumanizing than taking a picture without a person in it. My people-less photos don’t strike me as lonely, and I don’t feel that there is anything “missing” in such compositions. I can see these folks even when they are not there, and, if I do my job, so can those who view the results later.

Are such photographs “sad”, or merely a commentary on the transitory nature of things? Can’t you photograph a house where someone no longer lives and conjure an essence of the energy that once dwelt within those walls? Can’t a grave marker evoke a person as well as a wallet photo of them in happier times? I ask myself these questions, along with other crucial queries like, “what time is the game on?” or, “what do you have to do to get a beer in this place?” Some answers come quicker than others.

I can’t account for what amounts to “sad” or “lonely” when someone else looks at a picture. I try to take responsibility for the pictures I make, but people, while a key part of each photographic decision, sometimes do not need to serve as the decisive visual component in them. The moment will dictate. So, my answer to one of life’s most persistent questions is a polite, “why, dear, I do take pictures of people.”

Just not always.

THINGS ARE LOOKING DOWN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY, AND THE HABITS WE FORM IN ITS PRACTICE, BECOME A HUGE MORGUE FILE OF FOLDERS marked “sometimes this works” or “occasionally try this”, tricks or approaches that aren’t good for everything but which have their place, given what we have to work with in the moment.

Compositionally, I find that just changing my vantage point is a kind of mental refresher. Simply standing someplace different forces me to re-consider my subject, especially if it’s a place I can’t normally get to. That means, whenever I can do something easy, like just standing or climbing ten feet higher than ground level, I include it in my shooting scheme, since it always surprises me.

For one thing, looking straight down on objects changes their depth relationship, since you’re not looking across a horizon but at a perpendicular angle to it. That flattens things and abstracts them as shapes in a frame, at the same time that it’s exposing aspects of them not typically seen. You’ve done a very basic thing, and yet created a really different “face” for the objects. You’re actually forced to visualize them in a different way.

Everyone has been startled by the city shots taken from forty stories above the pavement, but you can really re-orient yourself to subjects at much more modest distances….a footbridge, a step-ladder, a short rooftop, anything to remove yourself from your customary perspective. It’s a little thing, but then we’re in the business of little things, since they sometimes make big pictures.

A SQUARE DEAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I WAS AT THE MORGAN LIBRARY IN NEW YORK earlier this week, combining a museum tour with a photo shoot, when I came upon an exhibit which featured one of the earliest Kodak consumer prints, with the image contained inside a circle, rather than the rectangular frames most of us remember. It reminded me that the very formatics of picture-making were, for a long time, dictated by the physical dimensions of either camera or film, and that, suddenly, we are free to make photographs of any proportions we choose, anytime, everytime.

It’s really an amazing liberation, and, as an ironic consequence, some photographers are choosing to return to the framing formats that they used to decry as too limiting, subjecting themselves to the extra discipline of staying within a boundary and adjusting their compositional priorities thusly. This has made for a kind of revival of the square image, and there seem to be some distinct advantages to the trend.

Shooting on the square means calling attention to the center of an image, to using symmetry to your advantage, and to paring your composition to its bare essentials. The negative space used in landscape or portrait modes can still work within a square image, but the subject, and your use of it, must be just right. Squaring off means calling immediate attention to your message, and making it all the stronger, since there’s nowhere else for the eye to go.

Andrew Gibson, writing for the website Digital Photography School, explains the visual appeal of the square:

Using the square format encourages the eye to move around the frame in a circle. This is different from the rectangular frame, where the eye is encouraged to move from side to side (landscape format) or up and down (portrait format). The shape of the frame is a major factor.

It’s odd to think of freeing up your photography by voluntarily working within a more restrictive format. And, unlike the old days of square-only shooting, the effect is largely created “after the click”, by re-composing through creative cropping. But the additional mindfulness can really boost the power of your images.

THE POLAROID EFFECT

BY MICHAEL PERKINS

I’VE BEEN TRYING TO FIND A WAY TO DESCRIBE THE COMBINATION OF HOPE AND ANXIETY THAT ATTENDS MY EVERY USE OF A SMARTPHONE CAMERA. Coming, as do many geezers of my era, from a tradition of full-function, hands-on, manual cameras, I have had a tough time embracing these miraculous devices, simply because of the very intuitive results that delight most other people.

But: it’s a little more complicated than my merely being a control freak or a techno-snob.

What’s always perplexing to me is that I feel that the camera is making far too many choices that it “assumes” I will be fine with, even though, in many cases, I am flat-out amazed at how close the camera delivers the very image I had in mind in the first place. It doesn’t exactly make one feel indispensable to the process of picture-making, but that’s a bug inside my own head and I gotta deal with it.

I think what I’m feeling, most of the time, is what I call the “Polaroid Effect”. To crowd around family or friends just moments after clicking off a memory with the world’s first true instant film cameras, those bulky bricks of the Mad Men era, was to share a collectively held breath: would it work? Did I get it right? Then as now, many “serious” photographers were reluctant to trust a Polaroid over their Leicas or Rolliflexes. Debate raged over the quality of the color, the impermanence of the prints, the limited lenses, the lack of negatives, and so on. Well, said the experts, any idiot can take a picture with this.

Well, that was the point, wasn’t it? And some of us “idiots” learned, eventually, to take good pictures, and moved on to other cameras, other lenses, better pictures, a better eye. But there was that maddening wait to see if you had lucked out with those square little glimpses of life. The uncertainty of trusting this…machine to get your pictures right.

And yet look at the above image. I asked a lot in this frame, with wild amounts of burning hot sunlight, deep shadows, and every kind of contrast in between just begging for the camera to blow it. It didn’t. I’m actually proud of this picture. I can’t dismiss these devices just because they nudge me out of my comfort zone.

Smartphone cameras truly extend your reach. They go where bulkier cameras don’t go, prevent more moments from being lost, and are in a constantly upward curve of technical improvement. People can and do make astounding pictures with them, and I have to remind myself that the ultimate choice…that of what to shoot, can never be taken away just because the camera I’m holding is engineered to protect me from my own mistakes.

TRY A DIFFERENT DOOR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PUBLIC PLACES, ESPECIALLY RECREATION SPACES, ARE A REAL STUDY IN IMAGE CONTROL. The world’s playgrounds and theme parks are, of course, in the business of razzle-dazzle, and their marquees, grand courts and official entrances are carefully crafted facades designed to delight. For photographers, that usually means we all take the same pictures of the same Magic Gate or Super Coaster or whatever. Great for convenience: not so great for photography.

I’m not saying that it’s impossible to improvise a different way to frame something new in shooting something overly familiar. But I am saying that sneaking around to the service entrance can have its points, too, offering a flavor of things that are a little funkier, a little less polished, a little less ready for prime time. I recall my dad, who, years ago, dreamed of taking the ultimate “real” shots of the circus, trolling around near some of the lesser-traveled entrances and halls, trying to catch the clowns and acrobats either just before or just after their time in the ring. I still pursue that strategy sometimes.

Pacific Park, the amusement center along the boardwalk at the Santa Monica pier, is a predictably colorful, semi-cheesy mix of carny sights and smells. The main foot traffic is straight down the pier to the fishing lookout, but there are alternate ways to get there along the back of the ride and games section. This shot is rather gauzy, as it’s taken through some sun-flecked netting, softening the color (and the appearance of reality) for some gaming areas. I took a lot of standard stuff on this day, but I keep coming back to this frame. It’s not a work of art, by any means, but I like the feeling that I’m not supposed to be there.

Of course, where I’m not supposed to be is, photographically, exactly where I want to be.

You never know when you might spy a clown without his rubber nose.

MINUTE TO MINUTE

Going, Going: Dusk giveth you gifts, but it taketh them away pretty fast, too. 1/40 sec., f/3.5, ISO 200, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

VOLUMES HAVE BEEN WRITTEN ABOUT THE WONDROUS PHENOMENON OF “GOLDEN HOUR“, that miraculous daily window of time between late afternoon and early evening when shadows grow long and colors grow deep and rich. And nearly all authors on the subject, whatever their other comments, reiterate the same advice: stay loose and stay ready.

Golden hour light changes so quickly that anything that you are shooting will be vastly different within a few moments, with its own quirky demands for exposure and contrast. Basic rule: if you’re thinking about making a picture of an effect of atmosphere, do it now. This is especially true if you are on foot, all alone in an area, packing only one camera with one lens. Waiting means losing.

The refraction of light through clouds, the angle of the sun as it speeds toward the horizon, the arrangement between glowing bright and super-dark….all these variables are shifting constantly, and you will lose if you snooze. It’s not a time for meditative patience. It’s a time for reactivity.

I start dusk “walkarounds” when all light still looks relatively normal, if a bit richer. It gives me just a little extra time to get a quick look at shots that may, suddenly, evolve into something. Sometimes, as in the frame above, I will like a very contrasty scene, and have to shoot it whether it’s perfect or not. It will not get better, and will almost certainly get worse. As it is, in this shot, I have already lost some detail in the front of the building on the right, and the lighted garden restaurant on the left is a little warmer than I’d like, but the shot will be completely beyond reach in just a few minutes, so in this case, I’m for squeezing off a few variations on what’s in front of me. I’ve been pleasantly surprised more than once after getting back home.

What’s fun about this particular subject is that one half of the frame looks cold, dead, “closed” if you will, while there is life and energy on the left. No real story beyond that, but that can sometimes be enough. Golden hour will often give you transitory goodies, with its more dramatic colors lending a little more heft to things. I can’t see anything about this scene that would be as intriguing in broad daylight, but here, the hues give you a little magic.

Golden hour is a little like shooting basketballs at Chuck E. Cheese. You have less time than you’d like to be accurate, and you may or may not get enough tickets for a round of Skee-Ball.

But hey.

TERMS OF ENGAGEMENT

Images that require little in the way of tweaking are good candidates for mobil phone cams. 1/30 sec., f/2.2, ISO 200, 4mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

OVER A HUNDRED YEARS AGO, WHEN EASTMAN KODAK’S AIM WAS TO PUT A CAMERA INTO THE HANDS OF THE AVERAGE EVERYMAN, their slogan, “You press the button, and we do the rest” was meant as an enticement. Not only had Kodak so simplified the processing of taking a snap as to make it irresistible, but they covered everything that happened next, allowing you to ship the camera, film inside, to them, at their cost, have them sweat the processing and printing, and ship back your photos, having also pre-loaded a fresh roll into your camera. You were covered at all ends, and this was a good thing. It was also an immensely successful thing for Kodak, which was, after all, not in the camera business, but in the film business (so shoot lots of it, hint hint).

Today’s camera phones are essentially the Kodak Brownies of the 21st century, with many refinements. Unlike the Brownie, the iPhone can intuit what you need in the way of light and aperture and supply it without troubling you with why or how it happens. Much like the box Kodaks of the Victorian era, today’s cameras are also bent on saving you the hassle of negotiating most decisions and choices. Again, this is a tremendously successful business plan, since it is safe to assume that most people would rather take the picture than think about how to take the picture.

But it is this very convenience that is a kind of strait jacket for photographers who were weaned on Pentaxes, Nikons and Canons, since, for us, the rules of engagement are lopsided. The camera is not meeting us in the middle as a co-creator or partner, but jamming us into a far corner, relegating us to the role of “the guy who hits the shutter”. Giving up all that active control can be freeing for some, but suffocating for others, and it speaks to the love-hate relationships many photogs have with their phones. On the one hand, Holy Hanna, looka these optics and ready-made tricks. On the other hand, you can feel that you’re just riding shotgun instead of steering.

With this in mind, I use an iPhone for the kind of street stuff where the concept or story is almost totally complete in itself, where I would only lose the moment or fiddle needlessly if carrying a more complex camera, or where the presence of a more obvious, “serious” camera would attract too much unwelcome attention. Damn ’em, phone cameras do buy you some invisibility and stealth, which is crazy, since much greater harm has been done by these ubiquitous little snoopercams than by all the “pro” cameras ever manufactured. Go figure.

When you take all the worry out of making a picture, you take all the responsibility and some of the joy out of it, too. My opinion, from my perch in the land of the dinosaurs. Cameras are not artists: they are tools, and when you give up the final say-so in what a picture will eventually be to a device, you get the recording of information, not the documentation of a soul.

GOING (GENTLY) OFF-ROAD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN YOU’RE BEHIND THE WHEEL, SOME PHOTOGRAPHS NAG THEIR WAY INTO YOUR CAMERA. They will not be denied, and they will not be silenced, fairly glowing at you from the sides of roads, inches away from intersections, in unexplored corners near stop signs, inches from your car. Take two seconds and grab me, they insist, or, if you’re inside my head, it sounds more like, whatya need, an engraved invitation? Indeed, these images-in-waiting can create a violent itch, a rage to be resolved. Park the car already and take it.

Relief is just a shutter away, so to speak.

The vanishing upward arc and sinuous mid-morning shadows of this bit of rural fencing has been needling me for weeks, but its one optimal daily balance of light and shadow was so brief that, after first seeing the effect in its perfection, I drove past the scene another half dozen times when everything was too bright, too soft, too dim, too harsh, etc., etc. There was always a rational reason to drive on.

Until this morning.

It’s nothing but pure form; that is, there is nothing special about this fence in this place except how light carves a design around it, so I wanted to eliminate all extraneous context and scenery. I shot wide and moved in close to ensure that nothing else made it into the frame. At 18mm, the backward “fade” of the fence is further dramatized, artificially distorting the sense of front-to-back distance. I shot with a polarizing filter to boost the sky and make the white in the wood pop a little, then also shot it in monochrome, still with the filter, but this time to render the sky with a little more mood. In either case, the filter helped deliver the hard, clear shadows, whose wavy quality contrasts sharply with the hard, straight angles of the fence boards.

I had finally scratched the itch.

For the moment….

NEAR MISS/NEAR SAVES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE PICTORIAL POTENTIAL OF SOME EVENTS, PHOTOGRAPHICALLY, TURNS OUT SOMEWHAT LESS MIRACULOUS THAN ADVERTISED. That is to say, a few of the things that you assume will certainly yield stunning image opportunities come off, in reality, with the majesty of, well, a flea circus. Sometimes, you think you’ll come home with the Seven Wonders Of The World inside your camera. Other times, you have to fight a strong urge to give up all this “pitcher-takin'” nonsense and take up honest work, like bank robbing, where you can at least set your own hours.

We’ve all been there.

Fairs, festivals, commemorations, parades…..these are all happenings which are ripe with potential, for which we have all camped out on the perimeter of what we hope and pray will be the Next Big Thing, only to come home with crumbs. Leavings. And the best thing to do when an event becomes a near-miss is to seek out what I call the “near saves”. That is, when the story at a given event is disappointingly small, go smaller….toward the intimate detail, the human component, the pertinent bit of texture or atmosphere. The overall panorama may fail, but a single face, a structural element, a series of shadows may deliver where the overall scene fails.

The above image happened almost by accident. Around early sunset, I rushed into an over-hyped cultural festival which failed to achieve full wonderfullness (trust me), and, hours after sunset, I was leaving in defeat, when, near the exit, I spotted a genuine, weirdo-beardo-freak-yourself-out gypsy fortune-telling machine, right out of Tom Hanks’ Big, wonderfully lit by ambient neon on the midway and the device’s own built-in “spook light”. The deepening dark of night was suddenly my best friend, boosting the mystery with oodles of deep shadow. With a 35mm prime lens, I could open clear up to f/1.8, keeping my ISO low at 100 and allowing me to get plenty of light at 1/40 of a second. I was amazed that I had walked right past this treasure when I entered the festival, but I was grateful for a second chance. Snap and done.

Thus,my best shots from the night were of anything but the main “attractions” of the event. Going small meant going beyond the obvious, the difference between a near miss and a near save.

The difference.

JUST ENOUGH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’VE PROBABLY SCRIBBLED MORE WORDS, IN THESE PAGES, ABOUT OVERCROWDED SHOTS than about any other single photographic topic, so if I sound like I’m testifyin’ in the Church-Of-I-Have-Seen-The-Light, bear with me. If any single thing has been a common theme in the last five years of my photography (or a factor in my negligible growth), it’s been the quest to take pictures that tell just enough, then back off before they become cluttered with excess visual junk.

Composing a photograph, when we start out as young budding photogs, seems to be about getting everything possible into the frame. All your friends. All the mountains and trees. Oh, and that cute dog that walked by. And, hey, those clouds, aren’t they something? Then, as we grow grayer of beard and thinner of scalp, the dead opposite seems to be true. We begin looking for things to throw away in the picture. Extra visual detours and distractions that we can pare away and, not only still have a picture, but, ironically, have more of a picture, the less we include. It’s very Zen. Or Buddhist. Or Zen Buddhist. Or something. Hey, I ain’t Depak Chopra. I just get a smidge better, as I age, at not making every image into a Where’s Waldo tapestry.

Especially in an age of visual overload, it’s too easy to make photographs that make your eye wander like a nomad all over the frame, unsure of where to land, of what to fix upon. Unable to detect the central story of the shot. Professionals learn this before any of the rest of us, since they often have to submit their work to editors or other unfeeling strangers outside their family who will tell them where their photos track on the Suck-O-Meter. There’s nothing like having someone that you have to listen to crumple up about 90% of your “masterpieces” and bounce them off your nose. Humility the hard way, and then some. But, even without a cruel dictator screaming in your ear that you ought to abandon photography and take up sewer repair, you can train yourself to take the scissors to a lot of your photos, and thereby improve them.

The image up top began with the truck occupying just part of what I hoped would be a balanced composition, showing it in the context of a western desert scene. Only the truck is far more interesting a subject than anything else in the image, so I cropped until the it filled the entire frame. Even then, the grille of the truck was worthy of more attention than the complete vehicle, so I cut the image in half a second time, squaring off the final result and shoving the best part of the subject right up front.

The picture uses its space better now, and, strong subject or weak, at least there is no ambiguity on where you’re supposed to look. Sometimes that’s enough. That’s Zen, too.

I think.

THE “EITHER/ORs”

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CAMERAS CAN EITHER TAKE CHOICE AWAY OR CHALLENGE YOU TO MASTER IT. If you’re a regular reader of this comic strip, you know all too well that I advocate making images with all manual settings rather than relying on automodes that can only come in a distant second to the human process of decision-making. People take better pictures with a camera than a camera can take alone. Can I get an Amen?

There is, of course, one choice you don’t get to make for any picture you create. You can’t mark a box called “the choice I made guarantees that everything in the image will work out.” Worse, there is always more than one choice being made in the creation of a photograph, and, even if you’re well-practiced and fast, you can’t make all of them perfectly. Choose one option and you are “un-choosing” another. The sum of the effect of all your choices together is what determines the final picture. That’s real work, and it certainly accounts for many people’s preference for automodes, since they obviate all those tough calls.

Nothing will force you to choose lots of options in short order like taking pictures of children at play. The image posted here, taken at a kindergarten playdate, shows a number of fast decisions that may or may not add up to an appealing picture, as lots of things are going on all at once. In the room where this was shot, space was tight, action was swift, white balances were wildly different in various zones within the room, and posing the kids in any way was absolutely impossible, due to their tender age and the fact that I wanted to be as invisible as possible, the better to catch their natural flow. To get pictures under this particular set of conditions, I had to decide how best to frame children who were grouping and ungrouping rapidly, where to get a fairly accurate register of color, customize my shutter speed and ISO with nearly every shot, and, as you see here, make my peace with whether the action implied in the shot outweighed the need for super sharpness.

You simply get into situations with some shots where you are not going to get everything you’d like to have, and you make decisions in the moment based on what each individual image seems to be “about”. Here I went for the joy, the bonding, the surging energy of the girls and let everything else take a back seat. Faced with the same situation seconds later, I might have remixed the elements to create a completely different result, but that is both the thrill and the bane of manual shooting. Automodes guarantee that you will get some kind of image, a very safe, if average, picture that allows you to worry less and possibly enjoy being in the moment to a greater degree….but you are the only factor than can take the photo to another level, to, in fact, take full responsibility for the result. It’s like the difference between taking a picture of Niagara Falls from your hotel room and taking it from a tightrope stretched across the raging waters.

And, ah, that difference is everything.

THE RELENTLESS MELT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE PEOPLE YOU PHOTOGRAPH BECAUSE THEY ARE IMPORTANT. Others are chosen because they are elements in a composition. Or because they are interesting. Or horrific. Or dear in some way. Sometimes, however, you just have to photograph people because you like them, and what they represent about the human condition.

That was my simple, solid reaction upon seeing these two gentlemen engaged in conversation at a party. I like them. Their humanity reinforces and redeems mine.

This image is merely one of dozens I cranked out as I wandered through the guests at a recent reception for two of my very dearest friends. Given the distances many of us in the room traveled to be there, it’s unlikely I will ever see most of these people again, nor will I have the honor of knowing them in any other context except the convivial evening that herded us together for a time. Because I was largely eavesdropping on conversations between small groups of people who have known each other for a considerable time, I enjoyed the privilege often denied a photographer, the luxury of being invisible. No one was asked to pose or smile. No attempt was made to “mark the occasion” or make a record of any kind. And it proved to me, once more, that the best thing to relax a portrait subject is……another portrait subject.

I assume from the body language of these two men that they are friends, that is, that they weren’t just introduced on the spot by the hostess. There is history here. Shared somethings. I don’t need to know what specific links they have, or had. I just need to see the echoes of them on their faces. I had to frame and shoot them quickly, mostly to evade discovery, so in squeezing off several fast exposures I sacrificed a little softness, partly due to me, partly due to the animated nature of their conversation. It doesn’t bother me, nor does the little bit of noise suffered by shooting in a dim room at ISO 1000. I might have made a more technically perfect image if I’d had total control. Instead, I had a story in front of me and I wanted to possess it, so….

Susan Sontag, the social essayist whose final life partner was the photographer Annie Liebovitz, spoke wonderfully about the special theft, or what she called the “soft murder” of the photographic portrait when she noted that “to take a photograph is to participate in another person’s mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.”

Melt though it might, time also leaves a mark.

Caught in a box.

Treasured in the heart.

Related articles

- Susan Sontag Musings Where You Least Expect Them (hintmag.com)

THE PARTY’S OVER

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY IS THE SCIENCE OF SECONDS. The seconds when the light plays past you. The seconds when the joy explodes. The seconds when maybe the building explodes, or the plane crashes. The micro moments of emotion’s arrivals and departures. Here it comes. There it goes. Click.

We are very good with the comings….the beginnings of babies, the opening of a rose, the blooming of a surprised smile. However, as chroniclers of effect, we often forget to also document the goings of life. The ends of things. The moment when the party’s over.

Christmas is a time of supreme comings and goings, and we have more than a month of ramp-up time each year during which we snap away at what is on the way. The gatherings and the gifts. The approaching joy. But a holiday this big leaves echoes and vacuums when it goes away, and those goings are photo opportunities as well.

This year, on 12/26, the predictably melancholy “morning after” found me driving around completely without pattern or design, looking for something of the magic day that had departed. I spun past the abandoned ruin of one of those temporary Christmas tree lots that sprout in the crevices of every city like gypsy camps for about three weeks out of the year, and something about all its emptiness said picture to me, so I got out and started bargaining with a makeshift cyclone fence for a view of the poles, lights and unloved fir branches left behind.

The earliness of the hour meant that the light was a little warmer and kinder than would be the case later on in the bleached-out white of an Arizona midday, so the scene was about as nice as it was going to get. But what I was really after was the energy that goes out of things the day the circus drives out of town. The holidays are ripe with that feeling of loss, and, to me, it’s at least as interesting as recording the joy. Without a little tragedy you don’t appreciate triumph, and all that. Christmas trees are just such an obvious measure of that flow: one day you’re selling magic by the foot, the next day you’re packing up trash and trailer and making your exit.

Photographs come when they come, and, unlike us, they aren’t particular about what their message is. They just present chances to see.

Precious chances, as it turns out.