BE THE CAMERA. NOW BE BETTER THAN THAT.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MERELY INVOKING THE NAME OF ANSEL ADAMS is enough to summon forth various hosannas and hallelujahs from anyone from amateur shutterbug to world-renowned photog. He is the saint of saints, the yardstick of yardsticks. He is the photographer was all want to be when (and if) we grow up. His technical prowess is held as the standard for diligence, patience, vision. And yet, even at the moment we revere Adams for his painstaking development of the zone system and his mind-blowing detail, we are still short-changing his greatest achievement.

And it is an achievement that many of us can actually aspire to.

What Ansel Adams did, over a lifetime, was work his equipment way beyond its limits, milking about 2000% out of every lens, camera and film roll, showing us that, to make photographs, we have to constantly reach beyond what we think is possible. Given the slow speed of much of the film stocks and lenses of his era, he, out of the wellspring of his own ingenuity, had to make up the deficit. He had to be smarter, better than his gear. No one piece of equipment could give him everything, so he learned over a lifetime how to anticipate every need. Look at one of many lists he made of things that he might need on a major shoot:

Cameras: One 8 x 10 view camera with 20 film holders and four lenses; 1 Cooke Convertible, 1 ten-inch Wide Field Ektar, 1 nine-inch Dagor, one six and three-quarters-inch Wollensak wide angle. One 7 x 17 special panorama camera with a Protar 13-1/2-inch lens and five holders. One 4 x 5 view camera with six lenses; a twelve-inch Collinear, including an eight-and-a-half Apo Lentar, a nine-and-a-quarter Apo Tessar, 4-inch Wide Field Ektar, Dallmeyer telephoto. One Hasselblad camera outfit with 38, 60, 80, 135, & 200 millimeter lenses. A Koniflex 35 millimeter camera. Two Polaroid cameras. 3 exposure meters (one SEI, two Westons).

Extras: filters for each camera: K1, K2, minus blue, G, X1, A, C5 &B, F, 85B, 85C, light balancing, series 81 and 82. Two tripods: one light, one heavy. Lens brush, stopwatch, level, thermometer, focusing magnifier, focusing cloth, hyperlight strobe portrait outfit, 200 feet of cable, special storage box for film.

Transport: One ancient, eight-passenger Cadillac station wagon with 5 x 9-foot camera platform on top.

However, the magic of Ansel Adams’ work is not in how much equipment he packed. It’s that he knew precisely what tool he needed for every single eventuality. He likewise knew how to tweak gear to its limits and beyond. Most importantly, his exacting command of the elemental science behind photography, which most of us now use with little or no thought, meant that he took complete responsibility for everything he created, from pre-visualization to final print.

And that is what we can actually emulate from the great man, that total approach, that complete immersion. If we use all of ourselves in every picture that we make, we can always be better than our cameras. And, for the sake of our art, we need to be.

DIGGING OUT OF THE DRYS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS, IN THE NATURAL COURSE OF THEIR CONTINUING DEVELOPMENT, will, at one point or another, get hopelessly lost. Stuck. Stranded on a desert island. Fumbling for the way out of the scary forest. Artistically adrift. Call it a dead spot, a dry spell, or shooter’s cramp, but you can expect to hit a stretch of it at some time. The pictures won’t come. You can’t buy an idea. And, worst of all, you worry that it will last……like forever.

At such times it’s a great idea to turn yourself into a rabid researcher. The answer to how to get unstuck is, really, out there. In your pictures or in someone else’s. Let’s look at both resources.

Your own past photographs are a file folder of both successes and failures. Pore over both. There are specific reasons that some pictures worked, and other’s didn’t. Approach them with a fresh eye, as if a complete stranger had asked you to assess his portfolio. And be both generous and ruthless. You’re looking for truth here, not a security blanket.

Beyond your own stuff, start drilling down to the divinity of your heroes, those legends whose pictures amaze you, and who just might able to kick your butt a little. And, just so we’re being fair, don’t confine yourself to studying just the gold standard guys. Make yourself look at a whole bunch of bad upstarts and find something, even a small thing, that they are doing right that you’re not. Discover a newbie who shoots like an angel, or an Ansel. Empathize with someone who needs even more help than you do. Once you have mercy on someone else’s lack of perfection, it’s a lot easier to forgive it in yourself.

We “artistes” love to believe that all greatness happens in isolation, just our art and us and the great god Inspiration. But even when you shoot alone, you’re in a kind of phantom collaboration with everyone else who ever took a picture. And that’s as it should be. Slumps happen. But the magic will come back. You just need to know how to reboot your mojo.

And smile. It’s photography, after all.

WHAT’S THIS I SEE?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS PHOTOGRAPHERS, WE HAVE A LIFETIME OF HEART-TO-HEART TALKS with ourselves, seeking the answer to questions like “what’s this I see?”, or “what do I want to tell?” Tricky thing is, of course, that, as time progresses, you are talking with a variety of conversational partners. As we age, we re-engineer nearly every choice-making process or system of priority. I loved Chef-By-Ar-Dee as an eight-year-old, but the sight of the old boy would probably make me gag at 63. And so it goes with clothing, choice of good reads, and, of course photography.

One of the things it’s prudent to do over the years is to take the temperature of present-day You, to really differentiate what that person wants in an image, versus what seemed essential at other stages in your life. I know that, in my case, my favorite photographers of fifty years ago bear very little resemblance to the ones I see as signposts today.

As a boy, I was in love with technical perfection and a very literal form of storytelling. Coming up in an artist’s household, I saw photos as illustrations, that is, subservient to some kind of text. I chose books for their pictures, yes, but for how well they visualized the writing in those books. The house was chock full of the mass-appeal photo newsmagazines of that day, from Life to Look to National Geographic to the Saturday Evening Post, periodicals that chose pictures for how well they completed the stories they decorated. A picture-maker for me, then, basically a writer’s assistant.

By my later school years, I began, slowly, to see photographs as statements unto themselves, something beyond language. They were no longer merely aids to understanding a writer’s position, but separate, complete entities, needing no intro, outro or context. The pictures didn’t have to be “about” anything, or if they were, it wasn’t a thing that was necessarily literal or narrative. Likewise, the kind of pictures I was interested in making seemed, increasingly, to be unanchored from reference points. Some people began to ask me, “why’d you make a picture of that?” or “why aren’t there any people in there?”

By this time in my life, I sometimes feel myself rebelling against having any kind of signature style at all, since I know that any such choice will eventually be shed like snake-skin in deference to some other thing I’ll deem important. For a while. What this all boils down to is that the journey has become more important than the destination, at least for my photography. What I learn is often more important than what I do about it.

And some days, I actually hope I never get where I’m going.

LESS STILL, MORE LIFE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHIC HISTORIANS WILL PROBABLY CRINGE AT MY OVER-SIMPLIFICATION, but I tend to believe that still-life compositions were originally popular to shooters because they solved a technical problem. At the dawn of the imaging art, recording media, from salted paper to glass plates, were so abysmally slow that exposure times stretched, in some cases, to nearly an hour. This meant that subject matter with any kinetic quality, from evolving landscapes to a baby’s face, were rendered poorly compared to inanimate objects. Still lifes were not so much about the beauty and color of fruit and cheese on a plate as they were about practicing…learning how to harness light and deliver a desired effect.

As film and lenses both sped up, a still life could be chosen purely on its aesthetic appeal, but the emphasis was still on generating a “realistic” image…an imitation of life. The 20th century cured both photography and painting of that narrow view, and now a still life, at least to me, offers the chance to transform mundane material, to force the viewer to re-imagine it. You can do this with various processes and approaches, but the main appeal to me is the chance to toss the object out of its native context and allow it to be anything…or nothing.

In the image at left, the home-grown vegetables, seen in their most natural state, actually have become alien to our pre-packaged notions of nutrition. They don’t even look like what arrives at many “organic” markets, much less the estranged end-product from Green Giant or Freshlike. And so we are nearly able to see these vegetables as something else. Weeds? Flowers? Decay? Design? Photographing them in our own way, we are free to assign nearly any quality to them. They might, for example, be suggestive of a floral bouquet, a far cry from the edibles we think we know. Still life compositions can startle when they are less “still” and more “life”, but we have to get away from our subjects and approach them around their blind side.

As always, it’s not what we see, but how.

SQUARE STORIES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

BETTER PHOTO HISTORIANS THAN ME WOULD BE ABLE to pinpoint the precise moment in time when the landscape-sized image first eclipsed the square image for most photo shooters. I’d tackle the search myself, but it’s late, and I’m about a martini and a half too far into relax mode, so there it is. But, regardless of the exact instant it first began to wane, the square is back, and bigger than ever, its refreshed use as a distinct mode of composition greeted like a revelation, rather than a return. Cool beans.

The unilateral quadrangle (I get wordy when I drink) managed to barely survive on the periphery of photography, even as the square-centric Polaroid print nearly wobbled out of existence, then came back, as hipsters in the lo-fi movement revived the use of instant print cameras. Then cel phones began offering a pre-selectable square setting for their cameras, and that became a thing. But the biggest boost for the square’s comeback came with a thing called Instagram. You may have heard about this quaint little app. I understand the developers made a few bucks on it.

Still, we are pretty universally conditioned to envision pictures in either “landscape” or (flip this up on its side) “portrait” modes, so much so that director Wes Anderson garnered as much press for his use of the old anamorphic aspect ratio in The Grand Budapest Hotel as he did for the movie’s content. Strangely, the square-format photograph is, upon its return, a bit of a retro novelty.

Composing a shot in roughly 1/3 less space than a landscape frame is a challenge, simply because we have fallen out of the habit for a few decades, but it does have a certain elegance. Lately, I have tried to use the square to effectively tell stories that I traditionally saw in vast or wide scenarios. Construction projects are one such case, in that they seem to call for wide angles and far reaching vistas, what we might call scope. The above image is my attempt to express most of what goes into a building project in what some would call cramped quarters. The main story elements, that is, the action, the range of tone, the compositional depth, are all present, but confined within the quadrangle. Of course, with a DSLR, I can’t start with a square, but I can envision where in the shot the best square is, and crop to it in post-processing.

Composing for a given dimension is a discipline, and, as such, it is valuable as a practice tool, since photographers should always be visualizing every possible way to get their story told. The square may be a prison. But it also may be an answer. The end result is what matters most.

THE EYE BACK OF THE LENS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY YEAR AT THIS TIME, AS I HIT THE RESET BUTTON ON MY LIFE VIA SOME KIND OF BIRTHDAY RITUAL, I pause to wonder, again, whether I’ve really learned anything at all in over fifty years of photography. Surely, by this late date, the habit of shooting constantly should have assured me that I had “arrived” at some place in terms of viewpoint or style, right? And yet, I still feel as if I am just barely inches off the starting line in terms of what there is left to learn, and how much more I need to know about seeing. It’s a great feeling in that it keeps things perpetually fresh, but I often wonder if I’ll ever make it to that mirage I see ever ahead of me.

The aging process, and how that continually remaps your perception, is one of the least pondered areas of criticism as it pertains to photography. And that’s very strange. We track the evolution of technical acuity over a lifetime. We date ourselves in reference to a piece of equipment we acquired, an influential person who crossed our path, or a body of work, but we don’t thoroughly examine how much our photography is being changed completely because the person making the picture is in constant flux. How can we ignore what seems to be the biggest shaper of our vision over time? We don’t even want the same things in an image from one year to the next, so how can we take photos in our maturity anything like those we shot in our youth?

Looking back to my first images, it’s clear that I thought the mere opportunity for a picture plus the act of clicking a shutter would result in a good picture, a kind of “cool view+camera=art” equation. This is to say that, instead of thinking, “I could make a good picture from this”, I was actually thinking, “this would be a good picture.” I know that sounds like hair-splitting of the first order, but the two statements are, in fact, different. The first implies that the camera plus the subject will automatically result in something solid; it’s a snapshot philosophy. The second statement is made by someone who has been frustrated by so many snapshots that he knows he has to step into the process as an active player. That realization can only come with age.

As always, my father’s admonition that art is a process rather than a product emerges as my prime directive. When I look at the pictures made by a twelve-year old me, I can at least see what the little punk was going for, and I can measure whether I’ve gotten any closer to that ideal than he did. The trick is for old me to want it as badly as young me did, and when that happens, I forget how many candles are on the cake, and am just grateful that their light still burns brightly.

THE VANISHED NORMAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE FUTURE DOESN’T ARRIVE ALL AT ONCE, just as the past doesn’t immediately vanish completely. In terms of technology, that means that eras kinds of smear across each other in a gradual “dissolve”. Consider the dial telephone, which persisted in various outposts for many years after the introduction of touch-tone pads, or, more specifically, Superman’s closet, the phone booth, which stubbornly overstayed its welcome long past the arrival of the cel. The “present” is always a mishmosh of things that have just arrived and things that are going away. They sort of pass each other, like workers at change of shift.

Photographically, this means that there are always relics of earlier eras that persist past their sell-by date. They provide context to life as part of a kind of ever-flowing visual history. It also means that you need to seize on these relics lest they, and their symbolic power, are lost to you forever. Everything that enjoys a brief moment as an “everyday object” will eventually recede in use to such a degree that younger generations couldn’t even visually identify it or place it in its proper time order (a toaster from 1900 today resembles a Victorian space heater more than it does a kitchen appliance).

Ironically, this is a double win for photographers. You can either shoot an object to conjure up a bygone era, or you can approach it completely without context, as a pure design element. You can produce substantial work either way.

Some of the best still life photography either denies an object its original associations or isolates it so that it is just a compositional component. The thing is to visually re-purpose things whose original purpose is no longer. Photography isn’t really about what things look like. It’s more about what you can make them look like.

THE ABCs OF A.B.S.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THIS IS THE TIME OF YEAR, IN THE DAYS OF FILM, WHEN THE EASTMAN KODAK COMPANY used to see a predictable surge in their annual sales, all tied to our ties to our loved ones. Each holiday season, the world’s biggest manufacturer of film reminded us that cameras were not only a great gift idea, they were the most important thing to be found under our respective Christmas trees. Their tremendously successful “Open Me First” ad campaign said it all: we couldn’t begin to truly experience all that family-centric holiday joy without a Kodak camera on hand to capture every giggle of surprise. The message was: shoot a lot of film. And if that doesn’t perfectly capture the perfect season, shoot more.

Ironically, it was the near death of film that finally freed us up from the single biggest constraint on our photographic freedom, that being the constraint of cost. Digital media, and the ease and ubiquity of cameras of all price points finally have freed the non-pros and the non-rich, making the admonition Always Be Shooting much more irresistibly urgent. We can afford miscalculations. We can afford do-overs. We can fix our worst mistakes without converting a hall bathroom into Dad’s Wide, Weird World Of Chemicals. We can gradually develop a concept over many “takes”, and we can salvage more of those visions. We can win more often.

The great photographer Ernest Haas once exhorted his students to “look for the ‘a-ha’ moment”, which meant not to be content with the first, or even the fifth framing of an idea in your viewfinder (okay, display screen). Asked in a lecture what the best wide-angle lens was, he quipped “two steps backward”, meaning that your best solution to a so-called technical problem is actually within yourself. Change your view, and change the outcome. The shot at the top of this post, as one example, only came at the end of ten other attempts at the same scene, all shot within a few minutes’ time. In the days of film, I would have had to settle for a much earlier version. I simply wouldn’t have kept clicking long enough to realize what I wanted from the subject.

Always Be Shooting doesn’t mean just clicking away madly, hoping that a jewel will magically emerge from a random batch of frames. It means keeping yourself in seeking mode long enough for ideas to emerge, then shooting beyond that to get those ideas right. Film made it possible to all of us to dream of capturing great memories. But it is the end of film that makes it possible for us to refine more of those memories before all those fleeting smiles have a chance to fade out of our reach.

BOUNTY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ALONG WITH DARK MEAT, CRANBERRY SAUCE, AND THE PERFECT YAM, I find unending Thanksgiving nourishment from the words of every photographer who has gone before me. And if this week marks our annual listing of gifts and gratitude, I would offer, as no less important than family and friends, the collected Wisdom Of Shooters Past as a hearty, ten-course meal for amateurs and professionals alike to feast on. It’s nice to remember that we are all trying to learn to see, and see well, and is an encouraging reminder that, behind all great lenses, there are great minds. The thought precedes the image, and, indeed, without that spark, we are all just mechanics.

Therefore, without further ado, ten noble sentiments on the fine art of harnessing light, for this day of thanks:

It is more important to click with people than to click the shutter.—-Alfred Eisenstaedt

Photographing a culture in the here and now often means photographing the intersection of the present with the past.–David Duchemin

A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know.—-Diane Arbus

One should really use the camera as though tomorrow you’d be stricken blind.–Dorothea Lange

A portrait is not made in the camera but on either side of it.–Edward Steichen

To me, photography is an art of observation. It’s about finding something interesting in an ordinary place… I’ve found it has little to do with the things you see and everything to do with the way you see them.—Elliot Erwitt

Your first 10,000 photographs are your worst.–Henri Cartier-Bresson

The eye should learn to listen before it looks.—Robert Frank

If the photographer is interested in the people in front of his lens, and if he is compassionate, that’s already a lot. The instrument is not the camera but the photographer.—Eve Arnold

Don’t pack up your camera until you’ve left the location.–Joe McNally

Happy Thanksgiving.

Stay hungry.

Always be seeing.

Always be shooting.

A KISS ON VETERAN’S DAY

A PICTURE, WHEN IT TRULY COMMUNICATES, isn’t worth a thousand words. The comforting cliché notwithstanding, a great picture goes beyond words, making its emotional and intellectual connection at a speed that no poet can compete with. The world’s most enduring images carry messages on a visceral network that operates outside the spoken or written word. It’s not better, but it most assuredly is unique.

Most Veteran’s Days are occasions of solemnity, and no amount of reverence or respect can begin to counterbalance the astonishing sacrifice that fewer and fewer of us make for more and more of us. As Lincoln said at Gettysburg, there’s a limit to what our words, even our most loving, well-intended words, can do to consecrate that sacrifice further.

But images can help, and have acted as a kind of mental shorthand since the first shutter click. And along with sad remembrance should come pictures of joy, of victory, of survival.

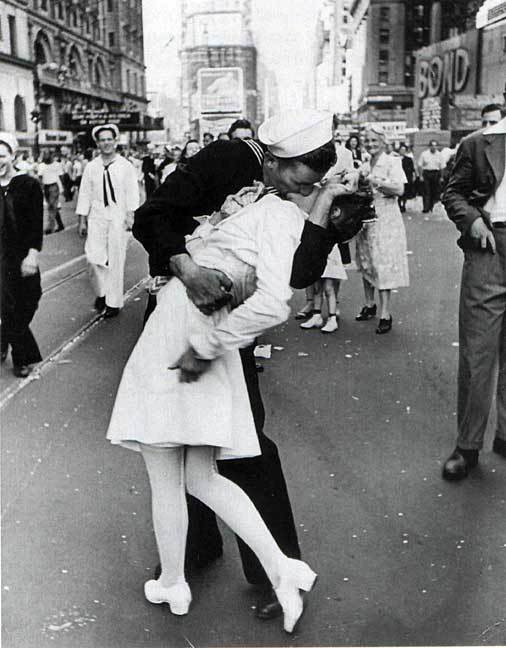

Of a sailor and a nurse.

Alfred Eisenstaedt, the legendary photojournalist best known for his decades at Life magazine, did, on V-J day in Times Square in 1945, what millions of scribes, wits both sharp and dull, couldn’t do. He produced a single photograph which captured the complete impact of an experience shared by millions, distilled down to one kiss. The subjects were strangers to him, and to this day, their faces largely remain a mystery to the world. “Eisie”, as his friends called him, recalled the moment:

In Times Square on V.J. Day I saw a sailor running along the street grabbing any and every girl in sight. Whether she was a grandmother, stout, thin, old, it didn’t make a difference. I was running ahead of him with my Leica, looking back over my shoulder, but none of the pictures that were possible pleased me. Then suddenly, in a flash, I saw something white being grabbed. I turned around and clicked the moment the sailor kissed the nurse. If she had been dressed in a dark dress I would never have taken the picture. If the sailor had worn a white uniform, the same. I took exactly four pictures. It was done within a few seconds.

Those few seconds have been frozen in time as one of the world’s most treasured memories, the streamlined depiction of all the pent-up emotions of war: all the longing, all the sacrifice, all the relief, all the giddy delight in just being young and alive. A happiness in having come through the storm. Eisie’s photo is more than just an instant of lucky reporting: it’s a toast, to life itself. That’s what all the fighting was about anyway, really. That’s what all of those men and women in uniform gave us, and still give us. And, for photographers the world over, it is also an enduring reminder from a master:

“This, boys and girls, is how it’s done.”

THE SHORT AND WINDING ROAD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY USED TO LITERALLY BE A MATTER OF MATH. Formulating formulae for harnessing light, predicting the reactivity of chemicals, calculating the interval between wretched and wonderful processing. And all that math, measured in materials, apprenticeship, and learning curves, was expensive. Mistakes were expensive. The time you invested to learn, fail, re-learn, and re-fail was expensive. All of it was a sustained assault on your wallet. It cost you, really cost you, in terms a math whiz could relate to, to be a photographer.

Now, the immediacy of our raw readiness to make a picture is astounding. Well, let’s amend that. To anyone picking up their first camera in the last thirty years, it’s pretty astounding. For those who began shooting ten years ago, it’s kinda cool. And for those falling in love with photography now, today, it’s……normal. Let’s pull that last thought out in the sunshine where we can get a good look at it:

For those just beginning to dabble in photography, the instantaneous gratification of nearly any conceptual wish is normal. Expected. No big deal. And the price of failure? Nil. Non-existent. Was there ever a time when it was a pain, or an effort just to make a picture, you ask Today’s Youth? Answer: not to my knowledge. I think it and I do it. If I don’t like it, I do it again, and again, faster than you can bolt down a burger on a commuter train. It’s just there, like tap water. How can I not be, why should I not be, absolutely fearless?

To take it further, Today’s Youth can learn more in a few months of shooting than their forebears could glean in years. And at an immeasurably small percentage of the sweat, toil, tears and financial investment. They can take a learning curve of rejected photos and failed concepts that used to be a long and winding road for pa and grandpa and compress it into a short and straight walk to the mailbox. And they are not sentimental, since they will not be spending enough time with any technology of any kind long enough to develop a weepy attachment for it, or for “how things used to be”. DSLR? Four-Thirds? Point and Shoot? Hey, anything that lets them take a picture is a camera. Make it so they can flap their eyelash and capture an image, and they’re in.

For some of us, hemmed in by experience, the limits of our technical savvy, and yes, our emotions, photography can be a somewhat formal experience. But for the many coming behind us, it’s just a reflex. A wink of the eye. Any and everything is an extension of their visual brain. Any and everything leads to a picture.

These new shooters will stop at nothing, will quake at nothing, will be awed by nothing, except ideas. They will be bold, because there is no reason not to be. They will take chances, since that, from their vantage point, is the only logical course. Photography is dead, long live photography.

The great awakening is at hand.

I’M INTO METAL, MAN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN I SAY THAT CURRENT DAY SHOOTERS ARE NOT HALF THE PHOTOGRAPHERS THAT THE OLD MASTERS WERE, that is not intended as an insult, but a simple bit of math. Given the fact that pioneers in the imaging game had to be equal parts artist and chemist, we only apply 50% of the effort these valiant visionaries did in negotiating the interactions of salts, albumens, bromides and other lab ingredients in an effort to even bring an image forth, much less do so with control. The technology that we employ today, and the speed and convenience with which we sling it around, should give us pause. The artistic mission of photography remains the same. It’s just that we don’t have to suffer as much for said art.

One of the marvelous processes from those years that still dazzles even the contemporary eye is the platinum print, so called because a platinum coating actually sits as a layer atop the developing papers, creating a print that contains a greater tonal range than any other monochrome process, including hints of gold, brown and red.Even better, what Kodachrome turned out to be for the archival permanence of color photography, platinum is for monochromatic images. It looks like a million bucks and will never degrade within the average person’s lifetime, or their great-grand kids’, neither. If you are over fifty and ever sat for a “serious” studio portrait, chances are you were immortalized in platinum. Literally speaking, you’re into metal, man.

Never for the timid (or the impecunious), platinum printing has largely faded (sorry) from the photographic scene along with the filmic science that birthed it, but, as with so many other “looks” in the digital era, things that were once merely processing are now content as well.

From where we stand, we can rifle through 200 years of processes and selectively decide to evoke an era or a mood a single picture at a time, just because we want to evoke a different time or place in our common cultural consciousness. We do this at our whim, unlike the people who actually devised the processes, who were stuck with them until they had (a) better knowledge of how to do things, (b) more money (c) both.

The digital apps that simulate the platinum print are gaining some popularity, as people apply instant alternate “mixes” of their cel phone shots, including up to a dozen different ways to envision a shot in monochrome. Those who appreciate the fine science in the original lab smarts required to create these looks in the film era claim that too little control resides in the user for a true one-to-one, film-t0-digital equivalency in any of these apps, but I have found that platinum creates a distinct, extra tool for monochrome fans, even if I experience guilt at not accruing the years of schooling it would have taken to do the process the “real way”. Anyway, above you will find a comparison between a basic mono rendering of an iPhone shot and a simulated platinum look, both cooked up in an app called AltPhoto. You may have a pref and you may not. That’s what makes horse races.

LOAD, LOCK, SHOOT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

OUR GRADE SCHOOL HISTORY CLASSES DRUMMED CERTAIN NAMES INTO OUR HEADS AS THE “EXCLUSIVE” CREATORS of many of the wonders of the modern age. We can still bark back many of those names without any prompting, saluting the Edisons, Bells, and Fords of the early part of the 20th century and the Jobses and Gateses of its final years. However, as we grew older, we realized that the births of many of our favorite geegaws (television, for example) can’t be traced to a single auteur. And when it comes to photography, their are too many fathers and mothers in all ends of the medium to even enumerate.

Several tinkerer-wizards do deserve singling out, however, especially when it comes to the mindset that all of us in the present era share that photography ought to be immediate and easy. And, in a very real way, both of these luxuries were born in the mind of a single man, Dean Peterson, who presided over half a dozen revolutions in the technology of picture making, most of his own creation. As an engineer at Eastman Kodak in the early ’60’s, Dean created and developed the Instamatic camera, and, in so doing, changed the world’s attitude toward photography in a way every bit as dramatic as George Eastman’s introduction of cheap roll film in the late 1800’s. Peterson’s new wrinkle: get rid of the roll.

Or, more precisely, get rid of loose film’s imprecise process for being loaded into the camera, which frequently ruined either single exposures or entire rolls, depending on one’s fumble-fingered luck. Peterson’s answer was a self-contained drop-in cartridge, pre-loaded with film and sealed against light. Once inside the camera, it was the cartridge itself that largely advanced the film, eliminating unwanted double-exposures and making the engineering cost of the host camera body remarkably cheap. Peterson followed Eastman’s idea of a fixed-focus camera with a pre-set exposure designed for daylight film, and added a small module to fire a single flashbulb with the help of an internal battery. Follow-up models of the Instamatic would move to flashcubes, an internal flash that could operate without bulbs or batteries, a more streamlined “pocket Instamatic” body, and even an upgrade edition that would accept external lenses.

With sales of over 70 million units within ten years, the Instamatic created Kodak’s second  golden age of market supremacy. As for Dean Peterson, he was just warming up. His second-generation insta-cameras, developed at Honeywell in the early ’70’s, incorporated auto-focus, off-the-film metering, auto-advance and built-in electronic flash into the world’s first higher-end point-and-shoots. His later work also included the invention of a 3d film camera for Nimslo, high-speed video units for Kodak, and, just before his death in 2004, early mechanical systems that later contributed to tablet computer design.

golden age of market supremacy. As for Dean Peterson, he was just warming up. His second-generation insta-cameras, developed at Honeywell in the early ’70’s, incorporated auto-focus, off-the-film metering, auto-advance and built-in electronic flash into the world’s first higher-end point-and-shoots. His later work also included the invention of a 3d film camera for Nimslo, high-speed video units for Kodak, and, just before his death in 2004, early mechanical systems that later contributed to tablet computer design.

Along the way, Peterson made multiple millions for Kodak by amping up the worldwide numbers of amateur photographers, even as he slashed the costs of manufacturing, thereby maximizing the profit in his inventions. As with most forward leaps in photographic development, Dean Peterson’s work eliminated barriers to picture-taking, and when that is accomplished, the number of shooters and the sheer volume of their output rockets ahead the world over. George Eastman’s legendary boast that “you press the button and we do the rest” continues to resonate through our smartphones and iPads, because Dean Peterson, back in 1963, thought, what the heck, it ought to be simpler to load a camera.

THE AGE OF ELEGANCE

If only we’d stop trying to be happy, we could have a pretty good time.——Edith Wharton

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LONG BEFORE HER NOVELS THE AGE OF INNOCENCE, ETHAN FROME, AND THE HOUSE OF MIRTH made her the most successful writer in America, Edith Wharton (1862-1937) was the nation’s first style consultant, a Victorian Martha Stewart if you will. Her 1897 book, The Decoration Of Houses, was more than a few dainty gardening and housekeeping tips; it was a philosophy for living within space, a kind of bible for combining architecture and aesthetics. Her ideas survive in tangible form today, midst the leafy hills of Lenox Massachusetts, in the Berkshire estate her family knew as “The Mount”.

Wharton only occupied the house from 1902 to 1911, but in that time established it as an elegant salon for guests that included Henry James and other literary luminaries. Although based on several classical styles, the house is a subtle and sleek counter to the cluttered bric-a-brac and scrolled busyness of European design. Even today, the house seems oddly modern, lighter somehow than many of the robber-baron mansions of the period. Many of its original furnishings went with Wharton when she moved to Europe, and have been replicated by restorers, often beautifully. But is in the essential framing and fixtures of the old house that the writer-artist speaks, and that is what led me to do something fairly rare for me, a photo essay, seen at the top of this page in the menu tab Edith Wharton At The Mount.

The images on this special page don’t feature modern signage, tour groups, or contemporary conveniences, as I attempt to present just the basic core of the estate, minus the unavoidable concessions to time. The house features, at present, an appealing terrace cafe, a sunlit gift store, and a restored main kitchen, as part of the conversion of the mansion into a working museum. I made no images of those updates, since they cannot conjure 1902 anymore than a Mazerati can capture the feel of a Stutz-Bearcat. The pictures are made with available light only, and have not been manipulated in any way, with the exception of the final shot of the home as seen from its rear gardens, which is a three-exposure HDR, my attempt to rescue the detail of the grounds on a heavily overcast day.

Take a moment to click the page and enter, if only for a moment, Edith Wharton’s age of elegance.

SYMBIOSIS OF HORROR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SHARPER MINDS THAN MINE WILL SPEND AN INFINITE AMOUNT OF EFFORT THIS WEEK CATALOGUING THE COSTS OF THE “GREAT WAR“, the world’s first truly global conflict, sparked by the trigger finger of a Serbian nationalist precisely one hundred years ago. These great doctors of thinkology will stack statistics like cordwood (or corpses) in an effort to quantify the losses in men, horses, nations and empires in the wake of the most horrific episode of the early 20th century.

Those figures will be, by turns, staggering/appalling/saddening/maddening. But in the tables of numbers that measure these losses and impacts, one tabulation can never be made: the immeasurable loss to the world of art, and, by extension, photography.

There can be no quantification of art’s impact in our lives, no number that expresses our loss at its winking out. Photography, not even a century old when Archduke Franz Ferdinand was dispatched to history, was pressed into service to document and measure the war and all its hellish impacts. But no one can know how many war photographers might have turned their lenses to beauty, had worldwide horror not arrested their attention. Likewise, no one can know how many Steichens, Adamses, or Bourke-Whites, clothed in doughboy uniforms, were heaped on the pyre as tribute to Mars and all his minions. Most importantly, we cannot know what their potential art, now forever amputated by tragedy, might have meant to millions seeking the solace of vision or the gasp of discovery.

Photography as an art was shaped by the Great War, as were its tools and techniques, from spy cameras to faster films. The war set up a symbiosis of horror between the irresistible message of that inferno and the unblinking eye of our art. We forever charged certain objects as emblems of that conflict, such that an angel now is either a winged Victory, an agent of vengeance, or a mourner for the dead, depending on the photographer’s aims. That giant step in the medium’s evolution matters, no less than the math that shows how many sheaves of wheat were burned on their way to hungry mouths.

Our sense of what constitutes tragedy as a visual message was fired in the damnable forge of the Great War, along with our ideals and beliefs. Nothing proves that art is a life force like an event which threatens to extinguish that life. One hundred years later, we seem not to have learned too much more about how to avoid tumbling into the abyss than we knew in 1914, but, perhaps, as photographers, we have trained our eye to bear better witness to the dice roll that is humanity.

RESTORING THE INVISIBLE

as[e The Wyandotte Building (1897), Columbus, Ohio’s first true skyscaper, seen here in a three-exposure HDR composite.

PHOTOGRAPHY IS ONE OF THE BEST RESPONSES TO THE DIZZYING SPEED OF CONTEMPORARY EXISTENCE. It is, in fact, because of a photograph’s ability to isolate time, to force our sustained view of fleeting things, that image-making is valuable as a seeing device that counteracts the mad rush of our “real time” lives. Looking into a picture lets us deal with very specific slices of time, to slowly take the measure of things that, although part of our overall sensory experience, are rendered invisible in the blur of our living.

I find that, once a compelling picture has been made of something that is familiar but unnoticed, the ability to see the design and detail of life is restored in the viewing of that thing. Frequently, in making an image of something that we are too busy to notice, the thing takes on a startlingly new aspect. That’s why I so doggedly pursue architectural subjects, in the effort to make us regard how much of our motives and ideals are captured in buildings. They stand as x-rays into our minds, revealing not only what we wanted in creating them, but what we actually created as they were realized.

In writing a book, several years ago, about a prominent midwestern skyscraper*, I was struck by how very personal these objects were…to the magnates who commissioned them, to the architects who brought them forth, and to the people in their native cities who took a kind of ownership of them. In short, the best of them were anything but mere objects of stone and steel. They imparted a personality to their surroundings.

The building pictured here, Columbus, Ohio’s 1897 Wyandotte Building, was designed by Daniel Burnham, the genius architect who spearheaded the birth of the modern steel skeleton skyscraper, heading up Chicago’s “new school” of architecture and overseeing the creation of the famous “White City” exposition of 1893. It is a magnificent montage of his ideals and vision for a burgeoning new kind of American city. As something thousand walk past every day, it is rendered strangely “invisible”, but a photograph can compensate for our haste, allowing us the luxury of contemplation.

As photographers, we can bring a particularly keen kind of witnessing to the buildings that make up our environment, no less than if we were to document the carvings and decorative design on an Egyptian sarcophagus. Architectural photography can help us extract the magic, the aims of a society, and experimenting with various methods for rendering their texture and impact can lead to some of the most powerful imagery created within a camera.

*Leveque: The First Complete Story Of Columbus’ Greatest Skyscraper, Michael A. Perkins, 2004. Available in standard print and Kindle editions through Amazon and other online bookstores.

ON SECOND THOUGHT…OR THIRD

I really preferred this as the color shot it originally was. Until I didn’t. Changing my mind took seconds.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST AMAZING BY-PRODUCTS OF DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY, a trend still evolving across both amateur and professional ranks, is a kind of tidal return to black-and-white imaging. The sheer volume of processing choices, both in-and-out-of-camera, have made at least dabbling in monochrome all but inevitable for nearly everyone, reversing a global trend toward near exclusive use of color that was decades in the making. At one point, to be sure, we chose black and white out of necessity. Then we embraced color and relegated B&W to the dustbin of history. Now, we elect to use it again, and increasing numbers, simply because everything technical is within our reach, cheaply and easily.

Looking back, it’s amazing how long it took for color to take hold on a mass scale. Following decades of wildly uneven experimentation and dozens of processes from Victorian hand-tinting to the Autochromes of the early 1900’s, stable and affordable color film came to most of us by the end of the 1930’s. However, there was a reluctance, bearing on tantrum, among “serious” photographers to embrace it for several more decades. This article from the Life magazine Library of Photography, a history-tutorial series from the 1970’s, discusses what can only be called photography’s original anti-color bias:

Although publishers and advertisers enhanced their messages with pictures in color during the first few decades of the color era, most influential critics and museum curators persisted in regarding color photographs as “calendar art”. Color, they felt, was, at best, merely decorative, suitable, perhaps, for exotic or picturesque subjects, but a gaudy distraction in any work with “serious” artistic goals.

Of course, for years, color printing and processing was also unwieldy and expensive, scaring away even those few artists who wanted to take it on. Still, can you imagine, today, anyone holding the belief that any kind of processing was a “gaudy distraction” rather than just one more way to envision an image? Color was once seen by serious photographers as an element of the commercial world, therefore somehow..suspect. Fashion and celebrity photography had not yet been seen as legitimate members of the photo family, and their explosive use of color was almost thought of as a carnival effect. Cheap and vulgar.

Of course, once color became truly ubiquitous, sales of monochromatic film plummeted, and, for a time, black-and-white found itself on the bottom bunk, minimized as somehow less than color. In other words, we took the same blinkered blindness and just turned it on its head. Dumb times two.

Jump to today, where you can shoot, process and show images in nearly one continuous flow of energy. There are no daunting learning curves, no prohibitive expenses, no chemically charred fingertips to slow us down, or segregate one kind of photography from all others. What an amazing time to be jumping into this vast ocean of possibilities, when images get a second life, upon second thought.

Or third.

BEYOND THE “OWIE”

Even if the people in the picture are not drunk, desperate, or dying, it’s still street photography.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SINCE THE CAMERA IS, FIRST AND FOREMOST, A RECORDING INSTRUMENT, it has always defaulted to the function of a journalist’s device, a reportorial machine for bearing witness to events. Certainly, it was inevitable that newspapers and magazines would, over time, turn to the camera as a way of marking or defining events, of making a visual document of things. And soon, of course, that simple recording process gave way to overt commentary, to an event being imbued with as much personal bias by a photographer as had always been the case with prose writers. It was possible for the camera to have an opinion.

Street photography, which allowed the amateur to stamp his view on what he saw no less than the professional journalist, should, certainly, have developed a judgemental eye toward the tragic, the awful in life. But, as often happens, it has spawned a school of thought in which people who fancy themselves “serious” artists reflect only rotting cities or crying children. This promotes a dishonest view of the world, since, sometimes, as Elton John once wrote, “the boulevard is not that bad.” And that makes our art lopsided. I call it “photographing OWIEs” (Orphans, Winos, Idiots and Eccentrics), and it has become something of a runaway industry.

It’s a popular conceit: only dour poets are “real” poets. Only depressed writers know anything of life. And only photographers who depict abject misery really “get” the human condition. This is flawed thinking, but invariably catches hold in every “authentic” gallery exhibit, every “honest” critical essay, and every other place pretentious humans congregate to celebrate their shared gravitas.

Street photography that reflects hope, or, God spare us, even a modicum of human normalcy should never be discounted or marginalized. Artists are charged with embracing both light and shadow. And certainly, for purely scientific reasons, photographs are impossible without taking both into account.

11/22/63: THE DAY THE WORLD UNSPOOLED

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ABRAHAM ZAPRUDER almost didn’t change history.

The Dallas women’s wear designer, a refugee from Soviet Russia and a Democrat, was eager to take a break from his office on November 22, 1963 to head down to the city’s Dealey Plaza, accompanied by his receptionist, to get a look at the man for whom he had voted three years earlier. An assistant suggested he first swing by his house and pick up his movie camera, a Bell & Howell Zoomatic “Director” Model 414 PD. Standing on a concrete pedestal, framing the presidential motorcade as it made its turn onto Elm Street, Zapruder, too stunned by what he was seeing through his viewfinder to even stop, captured 26.6 seconds that would document the world’s shift from innocence to agony.

He had no sophisticated experience documenting news stories. He had never taken a course on photography. Understandably, for the rest of his life, he could never again even bring himself to shoot either still or movie images. But that day, he had a camera. And if anything of Abraham Zapruder’s unique role in the Kennedy tragedy is emblematic of the fatefulness of photography, of being present when things are ready to happen, it is those 486 frames of Kodachrome, footage that no one….no news service, no network, no freelancer…nobody but a dressmaker with an amateur camera was poised to capture.

Because of Abraham Zapruder, the chaos and fear of those seconds now represent a time line, a sequence. The event has parameters, colors. Tone. Zapruder’s camera transformed him from “a” witness to “the” witness, the image maker of record, just as it had for others when the Hindenburg erupted into flame, the Arizona billowed black smoke, and, a generation later, Challenger painted the sky with a billion fiery atoms.

Half a century later, the multiplier effect of personal media devices guarantees that each key event in our history is documented by hundreds, even thousands of witnesses at once, but, on that horrible day in Dallas, Abraham Zapruder’s preservation of murder on celluloid was an outlier, an accident. And by the end of Friday, November, 22, 1963, the day the world unspooled, he was no longer merely a tourist taking a home movie. He was the sole possessor of Exhibit A.

Related articles

- Zapruder Film: Images As History, Pre-Smartphone (dfw.cbslocal.com)