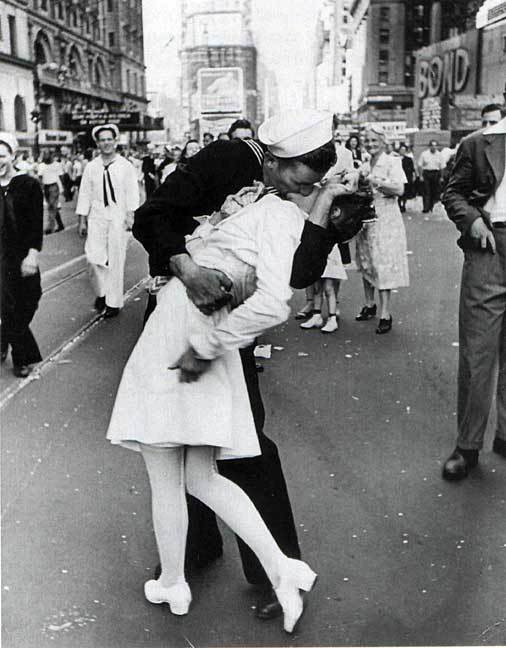

A KISS ON VETERAN’S DAY

A PICTURE, WHEN IT TRULY COMMUNICATES, isn’t worth a thousand words. The comforting cliché notwithstanding, a great picture goes beyond words, making its emotional and intellectual connection at a speed that no poet can compete with. The world’s most enduring images carry messages on a visceral network that operates outside the spoken or written word. It’s not better, but it most assuredly is unique.

Most Veteran’s Days are occasions of solemnity, and no amount of reverence or respect can begin to counterbalance the astonishing sacrifice that fewer and fewer of us make for more and more of us. As Lincoln said at Gettysburg, there’s a limit to what our words, even our most loving, well-intended words, can do to consecrate that sacrifice further.

But images can help, and have acted as a kind of mental shorthand since the first shutter click. And along with sad remembrance should come pictures of joy, of victory, of survival.

Of a sailor and a nurse.

Alfred Eisenstaedt, the legendary photojournalist best known for his decades at Life magazine, did, on V-J day in Times Square in 1945, what millions of scribes, wits both sharp and dull, couldn’t do. He produced a single photograph which captured the complete impact of an experience shared by millions, distilled down to one kiss. The subjects were strangers to him, and to this day, their faces largely remain a mystery to the world. “Eisie”, as his friends called him, recalled the moment:

In Times Square on V.J. Day I saw a sailor running along the street grabbing any and every girl in sight. Whether she was a grandmother, stout, thin, old, it didn’t make a difference. I was running ahead of him with my Leica, looking back over my shoulder, but none of the pictures that were possible pleased me. Then suddenly, in a flash, I saw something white being grabbed. I turned around and clicked the moment the sailor kissed the nurse. If she had been dressed in a dark dress I would never have taken the picture. If the sailor had worn a white uniform, the same. I took exactly four pictures. It was done within a few seconds.

Those few seconds have been frozen in time as one of the world’s most treasured memories, the streamlined depiction of all the pent-up emotions of war: all the longing, all the sacrifice, all the relief, all the giddy delight in just being young and alive. A happiness in having come through the storm. Eisie’s photo is more than just an instant of lucky reporting: it’s a toast, to life itself. That’s what all the fighting was about anyway, really. That’s what all of those men and women in uniform gave us, and still give us. And, for photographers the world over, it is also an enduring reminder from a master:

“This, boys and girls, is how it’s done.”

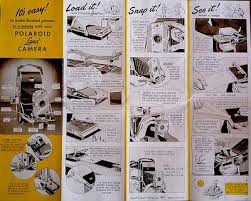

60 SECONDS TO HAPPINESS

The first of its kind: A model 95 Polaroid Land Camera, circa 1948. Light-painted in darkness for a 15 second exposure at f/5.6, ISO 100, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I REMEMBER, YEARS AGO, HEARING A COMMERCIAL FROM AN OLD RADIO SERIAL IN WHICH THE SPONSOR, Ovaltine, rhapsodized about the show’s latest mail-in “premium”, a genuine Captain Midnight Shake-Up Mug, which, according to the ad copy, was made of “exciting, new PLASTIC!!” It struck me, as a child of the ’50’s, that there actually had been a time when plastic was both exciting and new. The “latest thing” in an age which was bursting with latest things, an unparalleled era of innovation and miracle. Silly Putty. Rocket Ships. Television.

And your photographs….delivered in just one minute.

The introduction of the Polaroid Land Camera, Model 95, in 1948 was one of those “exciting, new plastic” moments. Developed by inventor Edward Land, the device was, amazingly, both camera and portable darkroom. Something mystical began to happen just after you snapped the shutter, an invisible, gremlins-in-the-machine process that accomplished the development of the image right in the camera. Open the back of the thing 60 seconds later, peel away the positive from the negative (a layer of developing gel lay in-between the them) and, sonofagun,you had a picture. Black and White only. Fragile, too, because you immediately had to dab it with a stick of smelly goo designed to keep the picture from browning and fading, a procedure which created the worldwide habit of fanning the picture back and forth to speed up the drying process (sing it with me: shake it like a Polaroid). And then you got ready for company. Lots of it.

When you brought a Model 95 (unofficially dubbed the “Speedliner”) to a party, you didn’t just walk in the door. You arrived, surrounded by an aura of fascination and wonder. You found yourself at the center of a curious throng who oohed and ahhed, asked endlessly how the damn thing worked, and remarked that boy, you must be rich. Your arrival was also obvious due to the sheer bulk of the thing. Weighing in at over a pound and measuring 10 x 5 x 8″, it featured a bellows system of focusing. Electronic shutters and compact plastic bodies would come later. The 95 was made of steel and leatherette, and was half the size of a Speed Graphic, the universal “press” cameras seen at news events. Convenient it wasn’t.

But if anything about those optimistic post-war boom years defined “community”, it was the Polaroid, with its ability to stun entire rooms of people to silent awe. The pictures that came out were, somehow, more “our” pictures. We were around for their “birth” like a roomful of attentive midwives. Today, over 75 years after its creation, the Polaroid corporation has been humbled by time, and yet still retains a powerful grip on the human heart. Unlike Kodak, which is now a hollowed out gourd of its former self, Polaroid in 2014 now makes a new line of instant cameras, pumping out pics for the hipsters who shop for irony on the shelves of Urban Outfitters. Eight photos’ worth of film will run you about $29.95 and someone besides Polaroid makes it, but it’s still a gas to gather around when the baby comes out.

So, a toast to all things “new” and “exciting”. But I’ll have to use a regular glass.

For some reason, I can’t seem to locate my Captain Midnight Shake-Up Mug.

EYE ON THE STARS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

Two men looked out from prison bars; one saw mud, and the other saw stars.–proverb attributed to Dale Carnegie

PHOTOGRAPHY WAS ONLY SEVERAL DECADES OLD WHEN IT WAS FIRST PRESSED INTO SERVICE to chronicle the world’s great comings and goings. The 19th century’s primitive print technology delayed the arrival of news photographs in the popular press for a while, but, once rotogravures and other methods caught up with the camera, the dizzying daily mix of wars, crimes, fancies and foibles that we call news began to be “illustrated” by photos, and we have never looked back since. If photography has a mission in the world, we came to believe, it is to use its unblinking eye to catch humanity in the act of behaving, well, like humanity. That reportorial bent, born in the 1800’s, still places a similar burden, by extension, on all photographers. We are supposed to Reveal The Facts, Get At The Truth, and Bear Witness.

So-called “street photography” has its roots in the works of crusading pioneers like Jacob Riis, the reporter turned photographer whose stark depiction of Manhattan slum life in the book How The Other Half Lives moved fellow reformers like Teddy Roosevelt to take action against that city’s brutal poverty. All these decades later, we place a certain trust in images that show the seamier or harsher side of life. Even those of us who aren’t officially campaigning to make the world a better place click off millions of “real” images of gritty cities, abandoned people, or hopeless conditions. We tend to regard these images as more authentic than the ones we create of things that poetic, or beautiful.

But this is a flawed viewpoint. We can, if we choose, look through the bars and see only the mud. But that doesn’t mean that marveling at the stars is any less important, or that beholding the beautiful is somehow a frivolous or non-serious pursuit. In fact, we need beauty to keep our souls from being crushed and rendering ourselves useless to do anything noble or good. Beauty is a template, a blueprint for the fulfillment of life, and we can’t even measure how far we’ve wandered toward the mud unless we know the distance we are from the stars.

Photography is “for” beauty, just as it is “for” everything else in human experience. We can, and should, be moved by cracked windows and wrecked alleys, to be sure, but it is our knowledge of the lark and the mountain that remind us why ugliness offends us. The fuller we are as humans, the better we are as photographers.

Don’t ignore the mud. That would be stupid. But keep your eyes, both yours and your camera’s, on the stars as well.

REAL PHONIES

Reality check: a retail mall in Hollywood, doubling as a tribute to D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance. huh?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“You’re wrong. She is a phony. But on the other hand you’re right. She isn’t a phony because she’s a real phony. She believes all this crap she believes.”

—Truman Capote, Breakfast At Tiffany’s

THE ABOVE REFERENCE TO MISS HOLLY GOLIGHTLY, she of the powder room mad money, also applies very neatly to Hollywood, California. The official kingdom of fakery has been in the business of fabricating fantasy for so long, it actually treats its hokum as holy writ. Legends and lore become facts of life, at least our collective emotional life. Dorothy’s ruby slippers (even though they were originally silver) draw more attention than actual footwear from actual persons. Wax figures of imaginary characters are viewed by more people than will ever examine the real remains of wooly mammoths at the La Brea Tar Pits. And, when it comes to the starstruck mini-Vegas that is the nexus of Hollywood Boulevard and Highland Avenue, even a fake of a fake seems like a history lesson.

Hollywood and Highland is one grand, loud, crude note of Americana, from its out-of-work actors sweating away in Wookie suits in front of the Chinese theatre to its cheesy Oscar paperweights at the souvie shops. This small stretch of carnival, high-caloric garbage chow, and surreal retail is a version of a version, a recreation of a creation, a “real phony” rendition of cinema, defined by its resurrection of the great gate of Babylon, which anchors a multi-level mall adjacent to the Dolby Theatre, the place where all those genuine cheesy paperweights are given each year. The gate and the two enormous white elephants that flank it are a partial replica of D.W. Griffith’s enormous set for the fourth portion of his silent 1916 epic Intolerance. The full set had eight elephants, an enormous flight of descending stairs, two side wings, and a crowd that may have originally inspired the term “cast of thousands”. That’s how they did ’em back in the day, folks. No matte paintings, no CGI, no greenscreen. We gotta build Babylon on the back set, boys, and we only got a week to do it, so let’s get cracking.

The original set, which stood at Hollywood and Sunset, was, by 1919, a crumbling eyesore and, in the city’s opinion, a fire hazard. Griffith, who lost his shirt on Intolerance, didn’t have the money to demolish it himself, and eventually it fell into sufficient disrepair to make knocking it down more cost-effective. Hey, who knew that it might make a great backdrop for a Fossil store 2/3 of a century later? But Hollywood never balks at the task of making a fake of a fake, so the Highland Center’s ponderous pachyderms overlook throngs of visitors who wouldn’t know D.W. Griffith from Merv Griffin from Gryffindor, and the world spins on.

Photographing this strange monument is problematic since nearly all of it is crawling with people at any given moment. Forget about the fact that you’re trying to take a fake image of a fake version of a fake set. Just getting the thing framed up is an all-day walkabout. So, at the end of my quest, what did I do to immortalize this wondrous imposter? Took an HDR to ramp up an artificial sense of wear and tear, and slapped on some sepia tone.

But it’s okay, because I’m a real phony. I believe all the crap I believe.

Hooray for Hollywood.

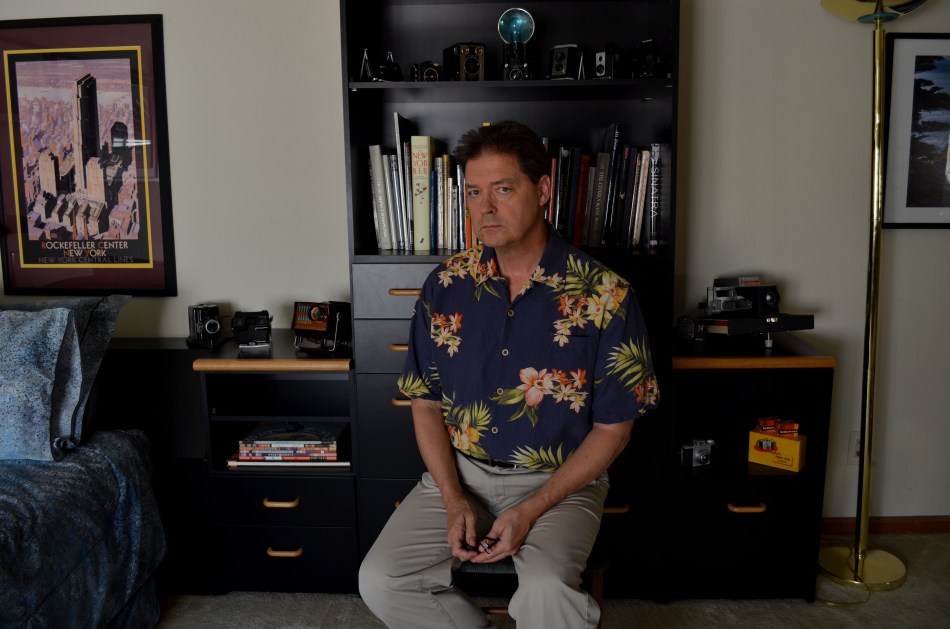

LOAD, LOCK, SHOOT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

OUR GRADE SCHOOL HISTORY CLASSES DRUMMED CERTAIN NAMES INTO OUR HEADS AS THE “EXCLUSIVE” CREATORS of many of the wonders of the modern age. We can still bark back many of those names without any prompting, saluting the Edisons, Bells, and Fords of the early part of the 20th century and the Jobses and Gateses of its final years. However, as we grew older, we realized that the births of many of our favorite geegaws (television, for example) can’t be traced to a single auteur. And when it comes to photography, their are too many fathers and mothers in all ends of the medium to even enumerate.

Several tinkerer-wizards do deserve singling out, however, especially when it comes to the mindset that all of us in the present era share that photography ought to be immediate and easy. And, in a very real way, both of these luxuries were born in the mind of a single man, Dean Peterson, who presided over half a dozen revolutions in the technology of picture making, most of his own creation. As an engineer at Eastman Kodak in the early ’60’s, Dean created and developed the Instamatic camera, and, in so doing, changed the world’s attitude toward photography in a way every bit as dramatic as George Eastman’s introduction of cheap roll film in the late 1800’s. Peterson’s new wrinkle: get rid of the roll.

Or, more precisely, get rid of loose film’s imprecise process for being loaded into the camera, which frequently ruined either single exposures or entire rolls, depending on one’s fumble-fingered luck. Peterson’s answer was a self-contained drop-in cartridge, pre-loaded with film and sealed against light. Once inside the camera, it was the cartridge itself that largely advanced the film, eliminating unwanted double-exposures and making the engineering cost of the host camera body remarkably cheap. Peterson followed Eastman’s idea of a fixed-focus camera with a pre-set exposure designed for daylight film, and added a small module to fire a single flashbulb with the help of an internal battery. Follow-up models of the Instamatic would move to flashcubes, an internal flash that could operate without bulbs or batteries, a more streamlined “pocket Instamatic” body, and even an upgrade edition that would accept external lenses.

With sales of over 70 million units within ten years, the Instamatic created Kodak’s second  golden age of market supremacy. As for Dean Peterson, he was just warming up. His second-generation insta-cameras, developed at Honeywell in the early ’70’s, incorporated auto-focus, off-the-film metering, auto-advance and built-in electronic flash into the world’s first higher-end point-and-shoots. His later work also included the invention of a 3d film camera for Nimslo, high-speed video units for Kodak, and, just before his death in 2004, early mechanical systems that later contributed to tablet computer design.

golden age of market supremacy. As for Dean Peterson, he was just warming up. His second-generation insta-cameras, developed at Honeywell in the early ’70’s, incorporated auto-focus, off-the-film metering, auto-advance and built-in electronic flash into the world’s first higher-end point-and-shoots. His later work also included the invention of a 3d film camera for Nimslo, high-speed video units for Kodak, and, just before his death in 2004, early mechanical systems that later contributed to tablet computer design.

Along the way, Peterson made multiple millions for Kodak by amping up the worldwide numbers of amateur photographers, even as he slashed the costs of manufacturing, thereby maximizing the profit in his inventions. As with most forward leaps in photographic development, Dean Peterson’s work eliminated barriers to picture-taking, and when that is accomplished, the number of shooters and the sheer volume of their output rockets ahead the world over. George Eastman’s legendary boast that “you press the button and we do the rest” continues to resonate through our smartphones and iPads, because Dean Peterson, back in 1963, thought, what the heck, it ought to be simpler to load a camera.

THE AGE OF ELEGANCE

If only we’d stop trying to be happy, we could have a pretty good time.——Edith Wharton

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LONG BEFORE HER NOVELS THE AGE OF INNOCENCE, ETHAN FROME, AND THE HOUSE OF MIRTH made her the most successful writer in America, Edith Wharton (1862-1937) was the nation’s first style consultant, a Victorian Martha Stewart if you will. Her 1897 book, The Decoration Of Houses, was more than a few dainty gardening and housekeeping tips; it was a philosophy for living within space, a kind of bible for combining architecture and aesthetics. Her ideas survive in tangible form today, midst the leafy hills of Lenox Massachusetts, in the Berkshire estate her family knew as “The Mount”.

Wharton only occupied the house from 1902 to 1911, but in that time established it as an elegant salon for guests that included Henry James and other literary luminaries. Although based on several classical styles, the house is a subtle and sleek counter to the cluttered bric-a-brac and scrolled busyness of European design. Even today, the house seems oddly modern, lighter somehow than many of the robber-baron mansions of the period. Many of its original furnishings went with Wharton when she moved to Europe, and have been replicated by restorers, often beautifully. But is in the essential framing and fixtures of the old house that the writer-artist speaks, and that is what led me to do something fairly rare for me, a photo essay, seen at the top of this page in the menu tab Edith Wharton At The Mount.

The images on this special page don’t feature modern signage, tour groups, or contemporary conveniences, as I attempt to present just the basic core of the estate, minus the unavoidable concessions to time. The house features, at present, an appealing terrace cafe, a sunlit gift store, and a restored main kitchen, as part of the conversion of the mansion into a working museum. I made no images of those updates, since they cannot conjure 1902 anymore than a Mazerati can capture the feel of a Stutz-Bearcat. The pictures are made with available light only, and have not been manipulated in any way, with the exception of the final shot of the home as seen from its rear gardens, which is a three-exposure HDR, my attempt to rescue the detail of the grounds on a heavily overcast day.

Take a moment to click the page and enter, if only for a moment, Edith Wharton’s age of elegance.

SYMBIOSIS OF HORROR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SHARPER MINDS THAN MINE WILL SPEND AN INFINITE AMOUNT OF EFFORT THIS WEEK CATALOGUING THE COSTS OF THE “GREAT WAR“, the world’s first truly global conflict, sparked by the trigger finger of a Serbian nationalist precisely one hundred years ago. These great doctors of thinkology will stack statistics like cordwood (or corpses) in an effort to quantify the losses in men, horses, nations and empires in the wake of the most horrific episode of the early 20th century.

Those figures will be, by turns, staggering/appalling/saddening/maddening. But in the tables of numbers that measure these losses and impacts, one tabulation can never be made: the immeasurable loss to the world of art, and, by extension, photography.

There can be no quantification of art’s impact in our lives, no number that expresses our loss at its winking out. Photography, not even a century old when Archduke Franz Ferdinand was dispatched to history, was pressed into service to document and measure the war and all its hellish impacts. But no one can know how many war photographers might have turned their lenses to beauty, had worldwide horror not arrested their attention. Likewise, no one can know how many Steichens, Adamses, or Bourke-Whites, clothed in doughboy uniforms, were heaped on the pyre as tribute to Mars and all his minions. Most importantly, we cannot know what their potential art, now forever amputated by tragedy, might have meant to millions seeking the solace of vision or the gasp of discovery.

Photography as an art was shaped by the Great War, as were its tools and techniques, from spy cameras to faster films. The war set up a symbiosis of horror between the irresistible message of that inferno and the unblinking eye of our art. We forever charged certain objects as emblems of that conflict, such that an angel now is either a winged Victory, an agent of vengeance, or a mourner for the dead, depending on the photographer’s aims. That giant step in the medium’s evolution matters, no less than the math that shows how many sheaves of wheat were burned on their way to hungry mouths.

Our sense of what constitutes tragedy as a visual message was fired in the damnable forge of the Great War, along with our ideals and beliefs. Nothing proves that art is a life force like an event which threatens to extinguish that life. One hundred years later, we seem not to have learned too much more about how to avoid tumbling into the abyss than we knew in 1914, but, perhaps, as photographers, we have trained our eye to bear better witness to the dice roll that is humanity.

THE TORQUOISE TIME TRAVELER

The wondrous Wiltern Theatre in Los Angeles. A three-exposure HDR to amplify time’s toll on the building’s exterior.

by MICHAEL PERKINS

SHE HAS WITHSTOOD THE GREAT DEPRESSION, A WORLD WAR, DECADES OF ECONOMIC UPS & DOWNS, and half a dozen owners (some visionaries and some bums), and still, the sleek green/blue terra-cotta wedge that is the Wiltern Theatre is one of the most arresting sights in midtown Los Angeles. From her 83-year old perch at the intersection of Western Avenue and Wilshire Boulevard, the jewel in the lower half of the old Pelissier building still commands attention, and, for lovers of live music, a kind of creaky respect. The old girl isn’t what she used to be, but she is still standing, as the same house that once hosted film premieres in the days of Cagney and Bogart now hosts alternative and edge, with pride.

And she still makes a pretty picture, lined face and all.

Opened in 1931 as a combination vaudeville house and flagship for Warner Brothers’ national chain of film theatres, The Warner Western, as it was originally named, folded up within a few years, re-opening in mid-Depression L.A. as the Wiltern (for Wilshire and Western) operating virtually non-stop until about 1956. As a vintage movie house, it had been equipped with one of the most elegant pipe organs in town, and enthusiasts of the instrument built a small following for the place for a while with recitals featuring the instrument. By the 1970’s, however, economies for larger-than-life flicker palaces were at an all-time low, and the Wiltern’s owners tried twice themselves to apply for permission to blow her down. Preservationists got mad, then got busy.

The Wiltern’s ticket kiosk sits under a plaster canopy of Deco sunrays. 1/40 sec., f/3.5, ISO 100, 18mm.

Restoration began in the 1980’s on the Pelissier building in general, but the Wiltern, with its ornate plaster reliefs and murals, had been so neglected over the years that its turnaround was slower. It was finally reborn in 1985 as a live performance theatre, losing some seat room but newly able to stage everything from brain-blaster garage rock to Broadway road productions and ballet.

I shot the Wiltern with three HDR frame, all f/5.6, with exposure times of 1/60, 1/100. and 1/160, and blended the final image in Photomatix to really show the wear and tear on the exterior. HDR is great for amplifying every flaw in building materials, as well as highlighting the uneven color that is an artifact of time and weather. I wanted to show the theatre as a stubborn survivor rather than a flawless fantasy, and the process also helped call attention to the building’s French Deco zigzags and chevrons. For an extra angle, I also made some studies of the glorious sunburst plaster ceiling over the outside ticket kiosk. It was great to meet the old girl at last, and on her own terms.

11/22/63: THE DAY THE WORLD UNSPOOLED

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ABRAHAM ZAPRUDER almost didn’t change history.

The Dallas women’s wear designer, a refugee from Soviet Russia and a Democrat, was eager to take a break from his office on November 22, 1963 to head down to the city’s Dealey Plaza, accompanied by his receptionist, to get a look at the man for whom he had voted three years earlier. An assistant suggested he first swing by his house and pick up his movie camera, a Bell & Howell Zoomatic “Director” Model 414 PD. Standing on a concrete pedestal, framing the presidential motorcade as it made its turn onto Elm Street, Zapruder, too stunned by what he was seeing through his viewfinder to even stop, captured 26.6 seconds that would document the world’s shift from innocence to agony.

He had no sophisticated experience documenting news stories. He had never taken a course on photography. Understandably, for the rest of his life, he could never again even bring himself to shoot either still or movie images. But that day, he had a camera. And if anything of Abraham Zapruder’s unique role in the Kennedy tragedy is emblematic of the fatefulness of photography, of being present when things are ready to happen, it is those 486 frames of Kodachrome, footage that no one….no news service, no network, no freelancer…nobody but a dressmaker with an amateur camera was poised to capture.

Because of Abraham Zapruder, the chaos and fear of those seconds now represent a time line, a sequence. The event has parameters, colors. Tone. Zapruder’s camera transformed him from “a” witness to “the” witness, the image maker of record, just as it had for others when the Hindenburg erupted into flame, the Arizona billowed black smoke, and, a generation later, Challenger painted the sky with a billion fiery atoms.

Half a century later, the multiplier effect of personal media devices guarantees that each key event in our history is documented by hundreds, even thousands of witnesses at once, but, on that horrible day in Dallas, Abraham Zapruder’s preservation of murder on celluloid was an outlier, an accident. And by the end of Friday, November, 22, 1963, the day the world unspooled, he was no longer merely a tourist taking a home movie. He was the sole possessor of Exhibit A.

Related articles

- Zapruder Film: Images As History, Pre-Smartphone (dfw.cbslocal.com)

11/22/63: THE DAY THE WORLD UNSPOOLED

Photomontage by Michael Perkins. Original Kennedy family image by Richard Avedon, now copyright The Smithsonian Institution. All rights reserved.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ABRAHAM ZAPRUDER almost didn’t change history.

The Dallas women’s wear designer, a refugee from Soviet Russia and a Democrat, was eager to take a break from his office on November 22, 1963 to head down to the city’s Dealey Plaza, accompanied by his receptionist, to get a look at the man for whom he had voted three years earlier. An assistant suggested he first swing by his house and pick up his movie camera, a Bell & Howell Zoomatic “Director” Model 414 PD. Standing on a concrete pedestal, framing the presidential motorcade as it made its turn onto Elm Street, Zapruder, too stunned by what he was seeing through his viewfinder to even stop, captured 26.6 seconds that would document the world’s shift from innocence to agony.

He had no sophisticated experience documenting news stories. He had never taken a course on photography. Understandably, for the rest of his life, he could never again even bring himself to shoot either still or movie images. But that day, he had a camera. And if anything of Abraham Zapruder’s unique role in the Kennedy tragedy is emblematic of the fatefulness of photography, of being present when things are ready to happen, it is those 486 frames of Kodachrome, footage that no one….no news service, no network, no freelancer…nobody but a dressmaker with an amateur camera was poised to capture.

Because of Abraham Zapruder, the chaos and fear of those seconds now represent a time line, a sequence. The event has parameters, colors. Tone. Zapruder’s camera transformed him from “a” witness to “the” witness, the image maker of record, just as it had for others when the Hindenburg erupted into flame, the Arizona billowed black smoke, and, a generation later, Challenger painted the sky with a billion fiery atoms.

Half a century later, the multiplier effect of personal media devices guarantees that each key event in our history is documented by hundreds, even thousands of witnesses at once, but, on that horrible day in Dallas, Abraham Zapruder’s preservation of murder on celluloid was an outlier, an accident. And by the end of Friday, November, 22, 1963, the day the world unspooled, he was no longer merely a tourist taking a home movie. He was the sole possessor of Exhibit A.

Related articles

- Zapruder Film: Images As History, Pre-Smartphone (dfw.cbslocal.com)

THE WOMAN IN THE TIME MACHINE

by MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE TIMES WHEN A CAMERA’S CHIEF FUNCTION IS TO BEAR WITNESS, TO ASSERT THAT SOMETHING FANTASTIC REALLY DID EXIST IN THE WORLD. Of course, most photography is a recording function, but, awash in a sea of infinite options, it is what we choose to see and celebrate that makes an image either mundane or majestic.

And then sometimes, you just have the great good luck to wander past something wonderful. With a camera in your hand.

The New York Public Library’s main mid-town Manhattan branch is beyond magnificent, as even a casual visit will attest. However, its beauty always seems to me like just “the front of the store”, a controlled-access barrier between its visually stunning common areas and “the good stuff” lurking in untold chambers, locked vaults and invisible enclaves in the other 2/3 of the building. I expect these two worlds to be forever separate and distinct, much as I don’t expect to ever see the control room for electrical power at Disneyland. But the unseen fascinates, and recently, I was given a marvelous glimpse into the other side at the NYPL.

A recent exhibit of Mary Surratt art prints, wall-mounted along the library’s second-floor hall, was somehow failing to mesmerize me when, through a glass office window, I peeked into a space that bore no resemblance whatever to a contemporary office. The whole interior of the room seemed to hang suspended in time. It consisted of a solitary woman, her back turned to the outside world, seated at a dark, simple desk, intently poring over a volume, surrounded by dark, loamy, ceiling-to-floor glass-paneled book shelves along the side and back walls of the room. The whole scene was lit by harsh white light from a single window, illuminating only selective details of another desk nearer the window, upon which sat a bust of the head of Michelangelo’s David, an ancient framed portrait, a brass lamp . I felt like I had been thrown backwards into a dutch-lit painting from the 1800’s, a scene rich in shadows, bathed in gold and brown, a souvenir of a bygone world.

I felt a little guilty stealing a few frames, since I am usually quite respectful of people’s privacy. In fact, had the woman been aware of me, I would not have shot anything, as my mere perceived presence, however admiring, would have felt like an invasion, a disturbance. However, since she was oblivious to not only me, but, it seemed, to all of Planet Earth 2013, I almost felt like I was photographing an image that had already been frozen for me by an another photographer or painter. I increased my Nikon’s sensitivity just enough to get an image, letting the light in the room fall where it may, allowing it to either bless or neglect whatever it chose to. In short, the image didn’t need to be a faithful rendering of objects, but a dutiful recording of feeling.

How came this room, this computer-less, electricity-less relic of another age preserved in amber, so tantalizingly near to the bustle of the current day, so intact, if out of joint with time? What are those books along the walls, and how did they come to be there? Why was this woman chosen to sit at her sacred, private desk, given lone audience with these treasures? The best pictures pose more questions than they answer, and only sparingly tell us what they are “about”. This one, simply, is “about” seeing a woman in a time machine. Alice through the looking-glass.

A peek inside the rest of the store.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

Thanks to THE NORMAL EYE’s latest follower! View NAFWAL’s profile and blog at :

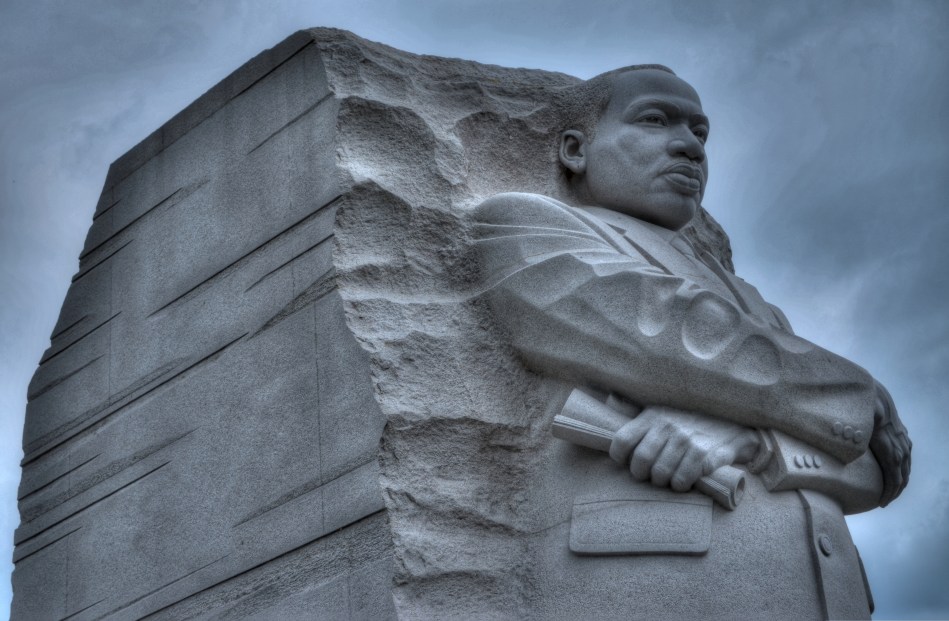

A TALE OF TWO KINGS

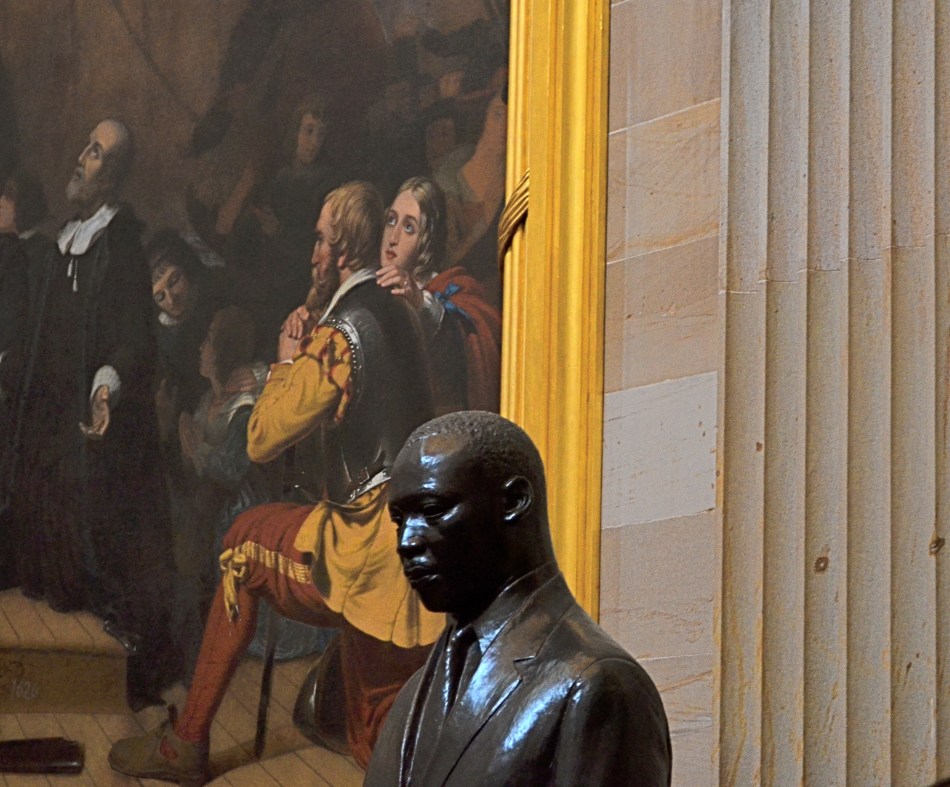

A determined Martin Luther King, Jr. stares forward into the future at the newly dedicated MLK Memorial on Washington’s National Mall. Fusion of three exposures, all with an aperture of f/5.6, all ISO 100, all 48mm. The shutter speeds, due to the high tones in the white statue, are 1/200, 1/320, and 1/500 sec.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

DEATH PERMANENTLY RENDERS REAL HUMAN BEINGS INTO ABSTRACTIONS. With every photo, formerly every painting, drawing, or statue of a renowned person, some select elements of an actual face are rearranged into an approximation, a rendering of that person. Not the entire man or woman, but an effect, a simulation. The old chestnut that a certain image doesn’t do somebody “justice”, or the mourner’s statement that the body in the casket doesn’t “look like” Uncle Fred are examples of this strange phenomenon.

Nothing amplifies that abstraction like having your image “officially” interpreted or commemorated after death, and, in the case of the very public Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Washington’s National Mall offers two decidedly contrasting ways of “seeing” the civil rights pioneer. One is more or less a tourist destination, while the other is muted, nearly invisible amongst the splendors of the U.S. Capitol. Both offer a distinct point of view, and both are, in a way, incomplete without the other.

The official MLK memorial, opened in 2011 as one of the newest additions to the Mall, stands at the edge of the Tidal Basin, directly across a brief expanse of water from the Jefferson Memorial. Its main feature shows a determined, visionary King, a titanic figure seeming to sprout from a huge slab of solid stone, as if, in the words of the monument, “detaching a stone of hope from a mountain of despair”. Arms folded, eyes fixed on a point some distance hence, he is calm, confident, and resolute. This gleaming white sculpture’s full details can best be captured with several bracketed exposures (fast shutter speeds) blended to highlight the grain and texture of the stone, but such a process abstract’s King even further into something out of history, majestic but idealized, removed.

Another view: a somber bronze bust of Dr. King in the U.S. Capitol rotunda, flanked by the painting The Embarkation Of The Pilgrims. 1/30 sec., f/5.6, ISO 640, 55mm.

The contrast could not be greater between this view and the bronze bust of King installed in 1988 in the rotunda of the Capitol building. This King is worried, subdued, straining under the weight of history, burdened by destiny. The bust gains some additional spiritual context when framed against its near neighbor, Robert Weir’s painting The Embarkation Of The Pilgrims, which shows the weary wayfarers of the Mayflower, bound for America, on bended knee, praying for freedom, for justice. Used as background to the bust, they resemble a kind of support group, a congregation eager to be led. Context mine? Certainly, but you shoot what you see. Inside the capitol, light from the dome’s lofty skylights falls off sharply as it reaches the floor, so underexposure is pretty much a given unless you jack up your ISO. Colors will run rich, and some post-lightening is needed. However, the dark palette of tones seems to fit this somber King, just as the triumphant glow of the MLK Memorial’s King seems suited to its particular setting.

Death and fame are twin transfigurations, and what comes through in any single image is more highly subjective than any photo taking of a living person.

But that’s where the magic comes in, and where mere recording can aspire to become something else.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

THE OTHER 50%

By MICHAEL PERKINS

The American Dream, Pacific Grove, California, 2012. A three-exposure HDR with shutter speeds ranging from 1/100 to 1/160, all three shots at f/8, ISO 100, 32mm.

THE LAST SUNDAY EDITION OF THE NEW YORK TIMES FOR 2012 features its annual review of the year’s most essential news images, a parade of glory, challenge, misery and deliverance that in some ways shows all the colors of the human struggle. Plenty of material to choose from, given the planet’s proud display of fury in Hurricane Sandy, the full scope of evil on display in Syria, and the mad marathon of American politics in an electoral year. But photography is only half about recording, or framing, history. The other half of the equation is always about creating worlds as well as commenting on them, on generating something true that doesn’t originate in a battlefield or legislative chamber. That deserves a year-end tribute of its own, and we all have images in our own files that fulfill the other 50% of photography’s promise.

This year, for example, we saw a certain soulfulness, even artistry, breathed into Instagram and, by extension, all mobile app imaging. Time ran a front cover image of Sandy’s ravages taken from a pool of Instagramers, in what was both a great reportorial photo and an interpretive shot whose impact goes far beyond the limits of a news event. Time and again this year, I saw still lifes, candids, whimsical dreams and general wonderments of the most personal type flooding the social media with shots that, suddenly, weren’t just snaps of the sandwich you had for lunch today saturated with fun filters. It was a very strong year for something personal, for the generation of complete other worlds within a frame.

I love broad vistas and sweeping visual themes so much that I have to struggle constantly to re-anchor myself to smaller things, closer things, things that aren’t just scenic postcards on steroids, although that will always be a strong draw for me. Perhaps you have experienced the same pull on yourself…that feeling that, whatever you are shooting, you need to remember to also shoot…..something else. It is that reminder that, in addition to recording, we are also re-ordering our spaces, assembling a custom selection of visual elements within the frame. Our vision. Our version. Our “other 50%.”

My wife and I crammed an unusual amount of travel into 2012, providing me with no dearth of “big game” to capture…from bridges and skyscrapers to the breathlessly vast arrays of nature. But always I need to snap back to center….to learn to address the beauty of detail, the allure of little composed universes. Those are the images I agonize over the most at years’ end, as if I am poring over thumbnails to see a little piece of myself , not just in the mountains and broad vistas, but also in the grains of sand, the drops of dew, the minutes within the hours.

Year-end reviews are, truly, about the big stories. But in photography, we are uniquely able to tell the little ones as well. And how well we tell them is how well we mark that we were here, not just as observers, but as participants.

It’s not so much how well you play the game, but that you play.

Happy New Year, and many thanks for your attention, commentary, and courtesy in 2012.

Related articles

- 10 social mobile photography trends for 2013 (davidsmcnamara.typepad.com)

- Old-Timer Joins Instagram, Schools Everyone With Poignant Flood Photos (wired.com)

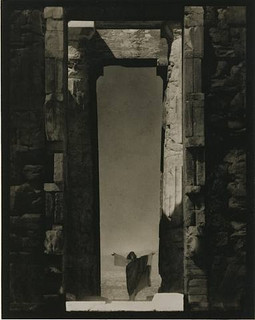

I SEE YOUR FACE BEFORE ME

Edward Steichen’s amazing 1921 portrait of dance icon Isadora Duncan beneath a massive arch of the Parthenon in Greece, an image which recently surged to the top of my mind. See a link to a larger view of this shot, below.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE IMAGES SIT AT THE BOTTOM OF THE BRAIN, LIKE STONE PILLARS IN THE FOUNDATION OF AN IMMENSE TOWER.The structures erected on top of them, those images we ourselves have fashioned in memory of these foundations, dictate the height and breadth of our own creative edifices. Between these elemental pictures and what we build on top of them, we derive a visual style of our own.

In my own case,many of the pillars that hold up my own house of photography come from a single man.

Edward Steichen is arguably the greatest photographer in history. If that seems like hyperbole, I would humbly suggest that you take a reasonable period of time, say, oh, twenty years or so, just to lightly skim the breadth of his amazing career….from revealing portraits to iconic product shots to nature photography to street journalism and half a dozen other key areas that comprise our collective craft of light writing. His work spans the distance from wet glass plates to color film, from the Edwardian era to the 1960’s, from photography as an insecure imitation of painting to its arrival as a distinct and unique art form in its own right.

At the start of the 20th century, Steichen co-sponsored many of the world’s first formal photographic galleries, and was a major contributor to Camera Work, the first serious magazine dedicated wholly to photography. He ended his career as the creator of the legendary Family Of Man, created in the early 1950’s and still the most celebrated collection of global images ever mounted anywhere on earth. He is, simply, the Moses of photography, towering above many lesser giants whose best work amounts to only a fraction of his own prodigious output.

Which is why I sometimes see fragments of what he saw when I view a subject. I can’t see with his clarity, but through the milky lens of my own vision I sometime detect a flashing speck of what he knew on a much larger scale, decades before. The image at left recently rocketed to my mind’s eye several weeks ago, as I was framing shots inside a large government building in Ohio.In 1921, Steichen journeyed to Greece to use the world’s oldest civilization basically as a prop for portraits of Isadora Duncan, then in the forefront of American avant-garde dance. Framing her at the bottom of an immense arch in the ruins of the Parthenon, he made her appear majestic and minute at the same time, both minimized and deified by the huge proportions in the frame. It is one of the most beautiful compositions I have ever seen, and I urge you to click the Flickr link at the end of this post for a slightly larger view of it. (Also note the link to a great overview of Steichen’s life on Wikipedia.)

Uplighting creates a moody frame-within-frame feel at the Ohio Statehouse building, in a shot inspired by Edward Steichen’s images of massive arches. 1/30 sec., f/8, ISO 800, 18mm.

In framing a similarly tall arch leading into the rotunda of the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus, I didn’t have a human figure to work with, but I wanted to show the building as a series of major and minor access cavities, in, around, under and through one of its arched entrance to the central lobby. I kept having to back up and step down to get at least a partial view of the rotunda and the arch at the opposite end of the open space included in the frame, which created a kind of left and right bracket for the shot, now flanked by a pair of staircases. Given the overcast sky meekly leaking grey light into the rotunda’s glass cupola, most of the building was shrouded in shadow, so a handheld shot with sufficient depth of field was going to call for jacked-up ISO, and the attendant grungy texture that remains in the darker parts of the shot. But at least I walked away with something.

What kind of something? There is no”object” to the image, no story being told, and sadly, no dancing muse to immortalize. Just an arrangement of color and shape that hit me in some kind of emotional way. That and Steichen, that foundational pillar, calling up to me from the basement:

“Just take the shot.”

Related articles

- The Photograph as a Social Statement (halsmith.wordpress.com)

- Picture Imperfect (andrewsullivan.thedailybeast.com)

- http://www.flickr.com/photos/quelitab/5793648357/lightbox/

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Steichen

SUM OF THE PARTS

No one home? On the contrary: the essence of everyone who has ever sat in this room still seems to inhabit it. 1/25 sec., f/5.6, ISO 320, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR ANNIE LIEBOVITZ, ONE OF THE WORLD’S MOST INNOVATIVE PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHERS, people are always more than they seem on the surface, or at least the surface that’s offered up for public consumption. Her images manage to reveal new elements in the world’s most familiar faces. But how do you capture the essence of a subject that can’t sit for you because they are no longer around…literally? Her recent project and book, Pilgrimage, eloquently creates photographic remembrances of essential American figures from Lincoln to Emerson, Thoreau to Darwin, by making images of the houses and estates in which they lived, the personal objects they owned or touched, the physical echo of their having been alive. It is a daring and somewhat spiritual project, and one which has got me to thinking about compositions that are greater than the sum of their parts.

Believing as I do that houses really do retain the imprint of the people who lived in them, I was mesmerized by the images in Pilgrimage, and have never been able to see a house the same way since. We don’t all have access to the room where Virginia Woolf wrote, the box of art chalks used by Georgia O’ Keefe, or Ansel Adams’ final workshop, but we can examine the homes of those we know with fresh eyes, finding that they reveal something about their owners beyond the snaps we have of the people who inhabit them. The accumulations, the treasures, the keepings of decades of living are quiet but eloquent testimony to the way we build up our lives in houses day by day, scrap by personal scrap. In some way they may say more about us than a picture of us sitting on the couch might. At least it’s another way of seeing, and photography is about finding as many of those ways as possible.

I spent some time recently in a marvelous old brownstone that has already housed generations of owners, a structure which has a life rhythm all its own. Gazing out its windows, I imagined how many sunrises and sunsets had been framed before the eyes of its tenants. Peering out at the gardens, I was in some way one with all of them. I knew nothing about most of them, and yet I knew the house had created the same delight for all of us. Using available light only, I tried to let the building reveal itself without any extra “noise” or “help” from me. It made the house’s voice louder, clearer.

We all live in, or near, places that have the power to speak, locations where energy and people show us the sum of all the parts of a life.

Thoughts?