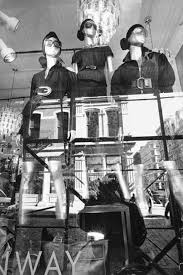

TWO-WAY GLASS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF THE EYES ARE THE WINDOW TO THE SOUL, then certain windows are an eye into contrasting worlds.

Photographers have devised a wide number of approaches when it comes to using windows as visual elements. Many choose to shoot through them with a minimum of glare, as if the glass were not there at all. Others use them as a kind of surreal jigsaw puzzle of reflected info-fragments.

To show these two approaches through the eyes of two great photographers, examine first Eugene Atget’s shots of 19th-century Paris storefronts, which mostly concentrated on shopkeeper’s wares and how they were arranged in display windows. Straightforward, simple. Then contrast Lee Friedlander’s 21st-century layered blendings of forward view and backward reflection (seen at left), which suspends the eye between two worlds, leaving the importance of all that mixed data to the viewer’s interpretation.

Much of my own window work falls into the latter category, as I enjoy seeing what’s inside, what’s outside, and what’s over my shoulder, all in the same shot. What’s happening behind the glass can be a bit voyeuristic, almost forbidden, as if we are not fully entitled to enter the reality on the other side of the window. But it’s interesting as well to use the glass surface as a mirror that places the shop in a full neighborhood context, that reminds you that life is flowing past that window, that the area is a living thing.

Thus, in an urban setting, every window is potentially two-way glass. Now, just because this technique serves some people as a narrative or commentary doesn’t make it a commandment. You have to use the language that speaks for you and to your viewer. Whatever kind of engagement serves that relationship best dictates how you should be shooting. I just personally find layered windows a fun sandbox to play in, as it takes the static quality away from a still photo to some degree, as if the image were imbued with at least the illusion of motion.

Sometimes it’s good to conceal more than reveal, and vice versa. The only “must”, for this or any other technique in photography, is to be totally mindful as you’re creating. Choose what you mean to do, and do it with your eyes fully open.

(LESS THAN) PRIME OPPORTUNITY

To Susan On The West Coast Waiting (2016). Shot from over 50 feet away with a 24mm wide-angle prime, then cropped nearly 70% from the original frame.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY DAY-LONG SESSION OF TRAVEL PHOTOGRAPHY dictates its own distinct rules of engagement. You can predict, to some degree, the general trend of the weather of the place where you’ll be staying/playing. You can pre-study the local attractions and map out at least a start-up list of things you might like to shoot. And you can choose, based on all your other prep, the equipment that will work best in the majority of situations, which keeps you from carting around every scrap of gear you own, saving reaction time, and, possibly, your marriage.

All well and good. However, even assuming that you make tremendously efficient choices about what lens you’ll most likely need on walkabout, there will be the occasional shot that is outside the comfort zone of said lens, something that it won’t do readily or easily. In such cases, the lens that would be perfect for that shot is likely forty miles away, back at your hotel. And here’s the place where you can pretty much predict what I advise.

Take the shot anyway.

I tend to work with a 24mm prime f/2.8 lens when walking through urban areas. It just captures a wider field within crowded streets, allowing me to grab most vistas without standing in the path of onrushing traffic (a plus) or spending a ton of time re-framing before each shot (a pain). This particular 24 was made in the ’70’s and is both lightning fast and spectacularly sharp, which, being a manual lens, also saves time and prevents mishaps.

24mm, to me, produces a more natural image than the wide end of the more popular 18-55 kit lenses being sold today, since there is less perspective distortion (straight lines remain straight lines). However, since it is a wide-angle, front-to-back distances will appear greater than they are in reality, so that things that are already in the distance seem even more so. And, since it is also a prime, there is no zooming. In the case at left, I wanted the girl’s bonnet, dress and presence on those rocks, but, if I was going to get any picture at all, plenty of other junk that I didn’t need would have to come along for the ride.

You deal with the terms in front of you at the time. Without a zoom, I either had to take the shot, with the idea of later cropping away the excess, or lose it altogether. There are times when you just have to visualize the final composition in your mind and extract it when it’s more convenient. Simply capture what you truly need within a bigger frame of stuff you don’t need, and fix it later. It’s a cornball cliché, but the only shot you are guaranteed not to get is the one you don’t go for. And this is also a good time to remember that it’s always smart to shoot at the biggest file size you can, allowing for plenty of pixel density even in the aftermath of a severe crop.

You can’t pre-plan all the potential pitfalls out of a photo vacation. Can’t be done. Come as close as you can, and trust your eye to help you rescue the outliers down the road.

But take the shot.

SOFTER AND QUIETER

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE MEANING OF THE WORD NOISE HAS, IN RECENT YEARS, been expanded beyond its familiar role as an audio term, extending its usage into our visual vocabulary as well. A key shift in photo terminology, as film converted to digital, has been the re-purposing of the word to denote a degradation in quality, with noise replacing grain as the way to describe a less-than-pristine image. Same idea, different wording.

And now, in recent years, I have heard the word used even more widely to denote weaknesses in a composition, describing a picture with too much information or distraction as “noisy”. In a recent post on the blog PhotographyMad.com, you find the following citation:

Often a photo will lack impact because the main subject is so small it becomes lost among the clutter of its surroundings. By cropping tight around the subject you eliminate the background “noise”, ensuring the subject gets the viewer’s undivided attention.

I personally would extend this metaphor to include not only the subject matter within a frame but its color range as well. That means, simply, that too many colors in an image might dilute the effect of a shot as much as the density of its elements, and extends the idea of noise to encompass anything that lessens the communicative power it has for the viewer.

In the above shot, the idea of the composition was to convey the bits of orange peel as some kind of spent or withered flower. I didn’t decide, in advance, to eat an orange in a yellow bowl, but I believe that the same peels in a red bowl might have hardened the look of the shot by calling attention to contrast instead of content. Keeping the entire composition to a two-tone color range (along with a decidedly shallow depth-of-field to reduce the texture detail) rendered it nice and soft. Of course there are a million ways to conceive this image; I just chose this way.

Noise is not merely a technical registration of visual or audio distortion. I think the word has real value if you’re looking to streamline your images. Just think noise=clutter.

Then turn down the volume.

BITE-SIZE BEAUTY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN PHOTOGRAPHY, WE OFTEN HAVE THE OPPORTUNITY TO ADMIRE THINGS THAT ARE, STRICTLY SPEAKING, beyond our capabilities. The world is rife with people who master exposure, composition, editing and conceptualization in ways which make us gasp in a mixture of awe and envy. Sometimes, we are so amazed by artists outside our own area of expertise that we emulate their passion and, in doing so, completely remake our own art. Other times, we just glimpse their greatness like a kid peeking inside the tent flap at the circus. We know that something marvelous is going on in there. We also sense that we are not a part of it.

That’s pretty much been my attitude toward landscape work.

Much of it leaves me impressed. Some of it leaves me breathless. All of it leaves me puzzled, since I know that I am missing a part of whatever mystical “something” it is that allows others to capture majesty and wonder in the natural world, their images looking “created” my own looking merely “snapped”.

Sometimes the sheer size of nature’s canvas panics my little puppy brain, and I retire to smaller stories.

It’s not the same with urban settings, or with anything that bears the mark of human creativity. I can instinctually find a story or a sweet point of focus in a building, a public square, a cathedral. I can sense the throb of humanity in these places and I can suggest it in pictures. But put me in front of a broad canvas of scenery and I struggle to carve out a coherent composition. What to include? What to cut? What light is best? And what makes this tree more pictorially essential than the other 3,000 I will encounter today?

The masters of the landscape world are magicians to me, crafty wizards who can charm the dense forest into some evocative choreography, summoning shadows and light into delicate interplay in a way that is direct, dramatic. I occasionally score out in the woods, but my failure rate is much higher, and the distance between what I see and what I can deliver much greater. Oddly, it was the work of scenic photographers, not street shooters or journalists, that originally conveyed the excitement of being a photographer to me, although I quickly devolved to portraits, abstractions, 3D, hell, anything to get me back to town, away from all that scary flora and fauna.

Medium or bite-sized natural subjects do better for me than vast vistas, and macro work, with its study of the very structures and patterns of organic things works even better. But I forever harbor a dream of freezing a forest in time in a way that stuns with its serene stillness and simple dignity. I have to keep putting myself out there, hoping that I can bridge the gap between envy and awareness.

Maybe I’ll start at the city park. I hear they have trees there….

TWO FOR LUNCH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHS DON’T HAVE TO BE ORGANIZED AROUND SYMMETRY, or even have a discernible “center” to them. However, the eye seems to find comfort in quickly settling on a “starting point” in an image, a place from which to proceed, or to be led to deeper discoveries.Designers for everything from magazine articles to websites toss around terms like visual weight and bottom-up processing to float various theories about how to direct the eye, with each system boasting top efficiency. A balanced pattern near the middle of the picture is thus not necessarily a “must-have”, just a fairly reliable “feels-right”.

By way of demonstration, a photographic center that consists of two people facing each other, talking, is a fairly easy anchor around which to build a straight narrative in an image. As the two heads arc left and right, a rough set of parentheses establish a very basic symmetry, and can help ensure that the middle of the picture engages the eye first. Based on architecture and surroundings, other things in the frame can either enhance or contrast with the symmetry in the middle, and that’s all a matter of taste for the photographer.

Many times a lunch counter or a restaurant gives me the talkers I need, so I tend to be on heightened alert when I enter such places. However, many of the photos I’ve made like this did not originally begin with the two people as the central emphasis: that happened in the cropping process.

In the above image, there actually was enough supportive symmetry from the background so centering the talkers and resizing the photo as a square seemed to be a good overall strategy. Of course, there is no hard and fast rule for these kinds of choices. All than can be said is that, for this picture, in this case, with these elements to work with, centering the conversationalists and placing them at the center of a square made sense. There is an entirely separate case to be made for selective use of the square as a compositional boost, and we’ll deal with than at another time.

Meanwhile, dropping in on two folks for lunch can act as a springboard for a certain kind of picture.

SEPARATE WORLDS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MAYBE IT’S THE TERM ITSELF. MAYBE IT’S HOW WE DEFINE IT. Either way, for photographers, concept of the “still life” is, let’s just say, fluid.

I believe that these static compositions were originally popular for shooters for the same reason that they were preferred by painters. That is, they stayed in one place long enough for both processes to take place. Making photographs was never as time-consuming as picking up a brush, but in the age of the daguerreotype the practice was anything but instantaneous, with low-efficiency media and optical limitations combining to make for looooong exposure times. Thus, the trusty fruit-bowl-and-water-jug arrangement was pretty serviceable. It didn’t get tired or require a bathroom break.

But what, now, is a “still life”? Just a random arrangement of objects slung together to see how light and texture plays off their surfaces? More importantly, what is fair game for a still life beyond the bowl and jug? I tend to think of arrangements of objects as a process that takes place anywhere, with any collection of things, but I personally seek to use them to tell a story of people, albeit without the people present. If you think about museum collections that re-create the world of Lincoln or Roosevelt, for example, the “main subject” is obviously not present. However, the correct juxtaposition of eyeglasses, personal papers, clothing, etc. can begin to conjure them in a subtle way. And that conjuring, to me, is the only appeal of a still life.

I like to find a natural grouping of things that, without my manipulation or collection, suggest separate worlds, completely contained universes that have their own tools, toys, architecture, and visual vocabulary. In the above montage of angles and things found at a beach resort, I had fun trying to find a way to frame the “experience” of the place, in abstract, showing all its elements without showing actual activities or people (beyond the sunbather at right). The real challenge, for me, is to create associations in the mind of the viewer that supply all the missing detail beyond the surfboards, showers, and sundecks. That, to me, is the real attraction of a still life….or, more accurately, taking a life and rendering it, fairly intact, in a still image.

Hey, it’s not that I don’t like a good bowl of fruit now and then. However, I think that one of photography’s best tricks is the ability to mentally conjure the thing that you don’t show, as if the bowl were to contain just apple cores and banana peels. Sometimes a picture of what has been can be as powerful as freezing an event in progress. But that’s your choice.

Which is another of photography’s best tricks.

A THING OF THE MOMENT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CAN YOU TRAIN YOUR EYE TO SEE FASTER? Now, by “seeing”, I mean a process which effectively goes beyond the mere reception of light or visual information, something unique to the process of photography. I’m asking if you can, in effect, train the eye to, if not actually see faster, to more efficiently communicate with the brain and the hand in selecting what is important, so more rapidly apprehend the fleeting moment when a picture must be made.

I’m talking about the gradually learned trick of deciding quicker what you want and when it might be near at hand.

Much has been written about Henri Cartier-Bresson’s idea of “the decisive moment”, the golden instant in which viewpoint, conditions, and subject converge to be especially eloquent….to be, in effect, the only true artistic moment at which a photograph can be taken. Many reject this idea out of hand, saying that there are many potential great opportunities in the space of even a few seconds, and that the lucky among us grab at least one now and then. For those people, it’s not so much “the” moment as “a” moment.

Whatever the nature of the near-perfect shot is, sensing when one is imminent isn’t magic, and it isn’t accidental. It’s also not guaranteed by talent or luck. It has to be the result of experience, more specifically, lots of unsatisfying experience. Because I feel that the pictures you didn’t get are far more instructive than the ones you did, simply because you burn more brain cells on the mysteries of what went wrong than you do on the miracle of getting things right.

This image is neither the result of great advance planning nor of great fortune: it’s somewhere in the middle, but it does record an instant when everything that can work is working. The light, the contrasting tones of white and gray, the framing, the incidental element of the passing tourist….they were all registering in my mind at the precise instant before I snapped the frame.

This does not mean I was totally in charge of the process: far from it. But I knew that something was arriving, something that would be gone in less than a second. Also, the elements that were converging to make the image were also in flux, and, having moved on, would result in something very different if I were to take a second or third crack at the same material.

For a photographer, it’s a little like surfing. You take lots of waves, with the idea that any of them can deliver the ride of your life. But, on any given day, all of them could be duds. However (and this is the part about a trained eye), you can learn to spot the best waves faster and faster, converting more of them to great rides. And making pictures is much the same process. You can’t absolutely analyze what will make a picture work, but you can learn to spot potential quicker, on some level between intentional and accidental.

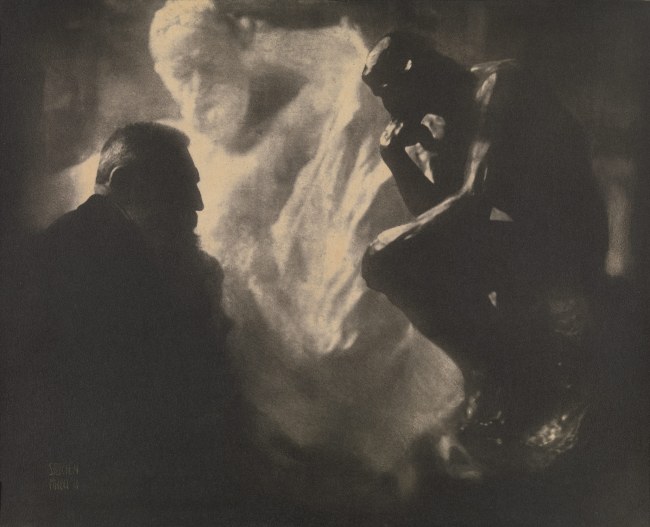

THE SHIFTING VEIL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS AND MAGICIANS SHARE A COMMON POWER, in that both of them selectively practice the art of concealment. Now you see it, now you don’t. Both the shooter and the shaman, in their own ways, know the importance of the slow reveal, the smooth manipulation of the viewer’s concept of reality. Best of all, they know how to choreograph and stage visual information. Here, they insist. Look here.

In a lifetime of studying portrait photographers, I have been fascinated by the nearly endless variety of approaches used to convey the human personality/soul in a static image. There are the formal studio sittings. There are the street ambushes of the paparazzo. And there are the shadowy, soft, gently suggestive pictures in which the classic representation of a “face” may not occur at all. This is the blending of revelation and mystery, and it is where portraits, at least for me, genuinely aspire to art.

He Decided To Wait (2016). A “self-portrait” in name only. Do we have to be the center of attention?

Some of my favorite images in this area were Edward Steichen’s studies with the sculpture Auguste Rodin, dark, smeary pieces of pure mood in which the great man was reduced to a near silhouette, as if he and his sculptures were forged out of the same raw material. I learn next to nothing of Rodin’s face from these pictures, and yet I learn worlds about his spirit. Steichen reveals as he conceals.

Which gives me an idea.

As I skim through the daily global tsunami of selfies, many of them simple grinning headshots, I see an incredible opportunity to start a completely new dialogue on what constitutes a portrait….or even a face. That opportunity will be squandered if 99% of selfies only look like slightly happier passport photos, rather than a real growth medium for investigating the self, for using the face as a compositional accent, an arranged object within a larger design.

Why selfies? Because the subject is always available. Because the technology of both mobile phones and conventional cameras allows for faster and more far-reaching experimentation. And because re-framing a subject you think you know intimately, merely by shifting where the veil lifts or falls, can be the difference between conceal and reveal.

GALLERYLABS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MUSEUMS AND GALLERIES COMPRISE SOME OF THE MOST INTERESTING WORKOUT SPACES for photographers, but for none of the reasons you might suppose. On the most obvious level, certainly,they are repositories of human endeavor, acting basically as big warehouses for things we deem important. But, beyond that, they are also laboratories for every kind of lighting situation, a big ‘ol practice pad for the mastery of lenses and exposure strategies. Sometimes the arrangement of color and shadow in some art houses is so drastically different from room to room that, even if there is nothing of note hanging on the walls, the walls themselves can frame amazing compositional challenges.

There is also a secondary, and fairly endless, source of photographic sketch work to be had in the people who visit public art spaces. The body language of their contemplative study of the artwork is a kind of mute ballet all its own, and no two patterns are alike. Watching the people who watch the art thus becomes a spectator sport of sorts, one which works to the advantage of the candid shooter, since people are more immersed in the paintings and thus a little less aware of themselves as regards the photographer. That leads to what I call “bodily candor”, a more relaxed quality in how they occupy their personal space.

Sometimes, as seen in the images in this article, your subject’s physical footprint is enough to express a full sense of the person without a trace of facial detail. In fact, I actually prefer this “no-face” approach, since it forces the viewer to supply some information of his own, making the photographs more interactive.

Try some gallerylab shots the next time you are hostage to a museum tour that was someone else’s idea of a good time. The exhibits themselves may disappoint, but the museum space and the people in it offer pretty consistent material.

CUES AND CLUES

Good Morning, Mr. Phelps (2016). How little of a tape recorder need be shown to convey a sense of that object?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SAY THE WORD “MINIMALISM” TO SOME PHOTOGRAPHERS, and you conjure visions of stark and spare compositions: random arrangements of light blobs, stray streaks of shadow, or scattered slivers of light, each conveying mood more than content. For some, these images are a kind of “pure” photography, while, for others, they are, to use a nice word, incoherent. Part of us always wants a picture to be, in some way, about something, and the word minimalism is charged, positively or negatively, depending on whether that “narrative thing” happens.

I actually associate minimalism with the formal storytelling process, but doing so with the fewest elements possible. It seems like a natural evolution to me, as I age, to make pictures talk louder with fewer parts. Simple cropping shows you how much more you can bring to an image by taking more of it away, and, with closeups and macro work, the message seems even clearer. Why show an entire machine when a cog carries the same impact? Why show everything when suggesting things, even leaving them out entirely, actually amps up the narrative power of a photograph?

Of course there are times when mere shape and shadow can be beautiful in themselves, and it doesn’t require a lot of windy theorizing to justify or rationalize that. Some things just are visually strong, even if they are non-objective. But minimalism based on our impressions or memory of very real objects, from a pocket watch to a piece of fruit, can allow us to tell a story with suggestions or highlights alone. If something is understood well enough, just showing a selectively framed slice of it, rather than the thing in its entirety, can be subtly effective and is worth exploring.

In the above image, you certainly understand the concept of a tape recorder well enough for me to excise the device’s chassis, controls, even half of its reel mechanism and still leave it “readable” as a tape recorder. You may find, upon looking at the picture, that I could have gone even farther in simplifying the story, and in your own work, you can almost certainly suggest vast ideas while using very small bits of visual information. Knowing the cultural cues and clues that we bring with us to the viewing process tells you how far you can stretch the concept.

ADDITION BY SUBTRACTION

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHIC COMPOSITION IS A CONSCIOUS PRIORITIZING OF EVERYTHING WITHIN A PICTURE’S FRAME, a ruthless process of demanding that everything inside that square justify its presence there. When we refer to the power of an image, we are really talking about the sumtotal of all the decisions that were made, beforehand, of what to include or lose in that image. Without that deliberate act of selection, the camera merely records everything it’s pointed at. It cannot distinguish between something essential and something extraneous. Only the human eye, synched to the human mind, can provide the camera with that context.

Many of our earliest photographs certainly contain the things we deem important to the picture, but they also tend to include much too much additional information that actually dilutes the impact of what we’re trying to show. In one of my own first photos, taken when I was about twelve, you can see my best friend standing on his porch…absolutely…..along with the entire right side of his house, the yard next door, and a smeary car driving by. Of course, my brain, viewing the result, knew to head right for his bright and smiling face, ignoring everything else that wasn’t important: however, I unfairly expected everyone else, looking at all the auxiliary junk in the frame, to guess at what I wanted them to zero in on.

Jump forward fifty years or so, to my present reality. I actively edit and re-edit shots before they’re snapped, trying to pare away as much as I can in pictures until only the basic storytelling components remain….that is, until there is nothing to distract the eye from the tale I’m attempting to tell. The above image represents the steps of this process. It began as a picture of a worn kitchen chair in a kitchen, then the upper half of the chair near part of a window in the kitchen, and then, as you see above, only part of the upper slats of the chair with almost no identifiable space around them. That’s because my priorities changed.

At first, I thought the entire kitchen could sell the idea of the worn, battered chair. Then I found myself looking at the sink, the floor, the window, and…oh, yeah, the chair. Less than riveting. So I re-framed for just the top half of the chair, but my eye was still wandering out the window, and there still wasn’t enough visible testimony to the 30,000 meals that the chair had presided over. So I came in tighter, tight enough to read the scratches and discolorations on just a part of the chair’s back rest. They were eloquent enough, all by themselves, to convey what I wanted, without the rest of the chair or anything else in the room to serve as competition. So, in this example, it took me about five trial frames to teach myself where the picture was.

And that’s the point, although I still muff the landing more often than I stick it (and probably always will). To get stronger compositions, you have to ask every element in the picture, “so what do you think you’re doing here?” And anyone who doesn’t have a good answer….off to the principal’s office.

STREET PHOTOGRAPHY (LITERALLY)

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NEIGHBORHOODS HAVE THEIR OWN VISUAL SIGNATURES, and photographers looking to tap into the energy of streets do well to give their locales a bit of advance study, the better to try to read an area’s particular identity. Sometimes the storytelling potential lies in a single building, even a part of a building. Other times it’s the mix of foot traffic. And, every once in a while, the saga of a street lies in the pavement itself.

New York City’s South Street Seaport district is drenched in local lore, tracing the contours of its alleys and warehouses to the beginnings of Manhattan’s first days as an international shipping destination. From the times of the Dutch’s tall-masted sailing vessels to the present mix of museum and modern retail, the port, on a typical day, offers color, texture, and a feeling of deeply rooted history that is a goldmine for photographers.

Of course, every neighborhood has its off days, and, on my recent trek to the area, a persistent, wind-driven rain had chased all but the hardiest locals off the streets and into the oaky timbers of the port’s quaint shops. Life on the street slowed to a crawl as iron-grey skies robbed the scene of its bolder hues. It was a day to huddle indoors with a good read and a hot cuppa anything. My camera, usually an unfelt burden around my beltline, began to drag like an anchor, stuffed into my woolen jacket to ward off the pelting drizzle, giving me the appearance of someone in sore need of a hip replacement.

Despairing of finding any vital activity along the street, I turned in desperation to the pavement itself, realizing that, in this eastward edge of Manhattan, the texture of the roads abandons the even concrete of most of the island and reverts to the cobbled brick textures of Melville’s time, with many old waterfront fixtures installed at curbside for extra atmosphere. Suddenly I had a little story to tell. The varied mix of firings in the brick, along with the steady rain, delivered the vivid color that was lacking in the area’s shops, allowing me to create an entire frame from just the street itself. Finding that some scale was needed, I sought out an old iron fixture for the left edge of the photo with just the legs and feet of two passing girls to balance out the right side. Suddenly there was enough, just enough of something to make a picture.

Obviously, if the street had been mere wet concrete or blacktop, the impact would have been different, and, were I in a different neighborhood, the street itself might have been unable to compete with the businesses for color or interest. On that morning, however, simple worked best, and my camera, at least for a moment, felt less like an anchor and more like a sailing ship.

THE FLEXIBLE FREEZE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS ACROSS THE LAST TWO CENTURIES HAVE CAPITALIZED ON ONE OF THEIR MEDIUM’S BEST TRICKS, the ability to freeze time, the sensation of carving out micro-seconds of reality and preserving them, like ancient scarabs trapped in amber. The thing known as “now”, with the aid of the camera, became something called “forever”, as things which were, by nature, fleeting were granted a kind of immortality. Events became exhibits, things to be studied or re-lived at our whim.

And yet, even as we extract these frozen moments, we mess around the edge of the illusion a bit, making still pictures also convey a sense of motion. Focus is a prime example of this retro-fitting of technique. No sooner had photography evolved the technical means to render sharp images than shooters began to put a little soft imprecision back into their pictures, by a variety of means: slow shutter speeds, time exposures, manual shaking, delayed flashes, and selective focus. Of all these techniques, at least for me, selective focus has proven to be the hardest to master.

….and two more lattes, 2016, shots on a Lensbaby Composer Pro, which allows a sweet spot of sharp focus to be moved anywhere in the frame the shooter desires.

Changing the messaging of a photographic story by using focus to isolate some elements and downplay others has always called for real practical knowledge of the workings of lenses and how they create focus as an effect. Recently, digital manipulation has allowed shooters to re-order the focal priorities of a shot after it’s taken, and in just the past few years, commercially available specialty lenses have allowed photographers to pre-select where and when focus will occur in an image, using it as interpretively as color or exposure.

I like to use the Lensbaby family of variable-focus lenses for what I call “flexible freeze” situations, times when focus can be massaged to create the illusion of speed. In the above shot, taken in a high-volume cafe, the small center of tight focus fans out to a near streaky quality at the outer edges of the picture. No one person is rendered sharp enough for features to register, or matter. What’s important here is the sensation of a busy lunch rush, which actually would be diminished if everything was in uniform focus.

Sharpness is certainly desirable in most cases for a strict re-creation of literal reality, but photography has never merely been a recording process. Focus can produce useful abstractions or atmospheres in a shot, so long as the effect serves the story. If it doesn’t help the image speak better, even a flexible freeze can quickly become a tiresome gimmick. Matching tools to goals is what good photography does best.

DEM DARN DONT’S

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE GLIB REMARK THAT YOU HAVE TO LEARN ALL THE RULES IN LIFE BEFORE YOU CAN BREAK THEM is maddeningly true, at least for me. Early on in my foto-fiddling, I was eager to commit all the world’s accumulated photographic do’s and don’ts to memory, like a biblical scholar nailing scripture passages, and shooting as if to enshrine those stone-written truths in art. I used words like always and never to describe how to make pictures in a given situation. I kept the faith.

And then, when I suddenly didn’t, my stuff stopped being pictures and started being photographs. Absolutes of technique are good starting places but they usually aren’t the best places to stick and stay for life. And at this point in my personal trek (seventh-inning stretch), I feel the shadow of all those do’s and don’ts swirling about like little guardian angels, but I worry first and foremost about what makes a given image work.

You no doubt have many pictures you’ve made which you simply like, despite the fact that they flaut, or even fracture, the rules. The above image, shot earlier this week at a multi-floor urban marketplace/eatery, struck me for two reasons. First, because of how many basic rules of “proper” composition it clearly violates; and secondly, just how much I don’t care, because I like what it does. To illustrate my point, I’ve provided citations from an article titled Principles Of Composition to cite specific ways that the photo is, well, wrong.

Have A Strong point of interest. Well, there isn’t any particular one, is there? Lots of conflicting stuff going on, but that’s the natural rhythm of this place. It’s a beehive. One man’s clutter is another man’s full “pulse of life”, and all that.

Don’t place the horizon line, or any strong vertical or horizontal lines, right in the middle of a picture. And make sure the lines aren’t tilted. Okay, well, since there is a distinct difference between the “level-ness” of the crossbeams over the lower floor and the slanted lines of the skylight above, there really isn’t a way to make the entire picture adhere to the same horizontal plane. However, the off-kilter sagginess of the old building actually lends it a little charm , unless I’m just drunk.

Keep compositions simple, avoiding busy backgrounds that distract from your subject. Granted, there are about five different sub-pictures I could have made into separate framings within this larger one, but that would defeat the object of overall bustle and sprawl that I experienced looking out over the entire scene. Sure, some compositions get so busy that they look like a page out of Where’s Waldo?, but certain chaotic scenes, from Grand Central Terminal to Picadilly, actually reward longer, deeper viewing.

Place a subject slightly off-center rather than in the middle of a photo. Yeah, well, that’s where that “strong point of interest” rule might have helped. Sorry.

Do these deviations mean the image was wrong, or wrong for certain circumstances? Every viewer has to call that one as he sees it. Me, I am glad I decided to shoot this scene largely as I found it. It needed to work with natural light, it needed to be shot wide and deep, and it needed to show a lot of dispirate activity. Done done and done. I heard all the rules in my head and chose the road not taken.

Or taken. I forget which.

PIECEWORK

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NO SELF-RESPECTING TOURIST SPOT IS COMPLETE WITHOUT A STROLL THROUGH the local craft shops, those kitschy little warrens of handmade goods from pottery to stone trinkets. Whether they are called “studios”, “boutiques” or “trading posts” these collections of gypsy creativity are on the main and minor drags of every destination town, and they are occasionally real feasts for the eye…and, in turn, the camera.

The stuff on the tables and counters is usually a riot of color and texture, and thus somewhat low-hanging fruit for photogs. But you can miss out if you limit your framings merely to the finished product, especially if the backstage or work areas, where the magic truly happens, are open or, even better, an active part of the customer experience. Lots of small craft factories, art sites, galleries and festivals incorporate the actual making of their goods into the overall tourist trip, and I often find these staging areas far more interesting than what eventually makes it to the sales floor.

Everyone recalls the corner pizzerias that oriented their kitchens so that the guy flipping the dough was in a display window near the street. It was great passive show biz and the same “backstage” allure still works for handmade jewelry and other crafts. And, while witnessing the literal creation of objects is one kind of storytelling opportunity, a quieter one can occur when you cruise past vacant desks whose tops are cluttered with tools and decorative components. These kind of still-life subjects are ripe with potential, since they show what is about to happen. They’re also displays of someone’s personal work area, their most individual arrangement of space.

Sometimes the best part of a shopping experience is the unpolished part. Pictures are where you find them, and opportunities reveal themselves when you start looking beyond the obvious locations.

SIMPLEST TERMS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ENTIRE BOOKSHELVES OF MATERIAL HAVE BEEN WRITTEN on the mysterious art of composition at it applies to photography. The variations are endless: what to shoot, how much to shoot, how to determine how little to shoot, theories on addition, subtraction, choice of subject, and so on. The only constant is that every compositional inclusion also embodies an exclusion. When you choose one thing, you un-choose everything else.

One such choice is that of color over monochrome, an argument which raged over a large part of the early 20th century, since, for many years, photographers thought they could rely upon black and white, even though an abstraction of reality, to convey a consistent feel, whereas early color films often produced uneven results. Some photographers decided to ban color altogether, to embrace the predictable un-reality of b&w rather than gamble on hues that might not be reproduced or printed with true fidelity, or worse, register as too brassy or garish. Today we seldom choose monochrome over color for the same reasons, but compositions still rise and fall on whether we use color, as well as what kind of color we use.

Sometimes, just as a photograph that’s poorly cropped or loosely composed can be too busy, a color scheme that has too much variety can prove distracting, actually diluting a picture’s impact. Occasionally, I like to see how few distinct colors I can use in an image and still consider it complete, as in the case of the tomatoes above, which makes it case with only red and green values. In this instance, adding extra space around the box holding the tomatoes, or expanding the frame to include other shapes, objects or hues, will do nothing to improve the strength of my composition, so why include them? This is an easy editing choice that occurs in real time in the framing of the shot, and, with the instant feedback afforded by digital, you know immediately if the picture is lacking anything.

The problem with a lot of photography is that we tend to go no further than framing up an “acceptable” picture, one that doesn’t overtly fail. However, the more we practice a mindful approach to composition, the more adept we get at putting just enough, from subject to hue, into the image, and not one item more. This gives our photographs a streamlined communicative power that directs the eye and conveys the story.

IT’S ALL WRONG BUT IT’S ALL RIGHT

I decided in the moment to go soft with this nature scene. Maybe I overdid it. Maybe it’s okay. Or not.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE ONLY CONSTANTS OVER THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY has been the flood tide of tutorial materials covering every aspect of exposure, composition, and light. The development of the early science of capturing images in the 19th century was accompanied, from the first, by a staggering load of “how to” literature, as the practice moved quickly from the tinkering of rich hobbyists to one of the most democratic of all the art forms. In little more than a generation, photography went from a wizard’s trick to a series of simple steps that nearly anyone could be taught.

In calling these pages the “photoshooter’s journey from taking to making”, we have made, with The Normal Eye, a deliberate choice not to add to the mountainous load of technical instruction that continues to be available in a variety of classroom settings, but to emphasize why we make photographs. This is not to say that we don’t refer to the so-called “rules” that govern the basics of creating an image, but that we believe the motives, the visions behind our attempts are even more important than just checking items off a list of techniques in the name of doing something “right”. There are many technically adept pictures which fail to engage on an emotional or aesthetic level, so the mission of The Normal Eye, then, is to start discussions on the “other stuff”, those indefinable things that make a picture “work” for our hearts and minds.

The idea of what a “good picture” is, has, over time, drifted far and wide, from photographs that mimic reality, to those that distort and fracture it, to images that are both a comment and a comment on a comment. It’s like any other long-term relationship: complicated. Like everyone else, I occasionally produce what I call a “fence-sitter” photo like the one above, which I can both excuse and condemn at the same time.

In raw technical terms, I have obviously violated a key rule with the abject softness of the image…..unless……unless it can be said to work within the context of the other things I was seeking in this subject. I was trying to stretch the envelope on how soft I could make the mix of dark foliage and hazy water in the scene, and, while I may have gone a bit too far, I still like some of what that near-blur contributes to the saturated color and lower exposure, the overall quiet tone I was trying for. Still, as of this moment, I’m still not sure whether this one is a hit or a miss. It might be on the way to something, but I just can’t say.

But that’s what the journey is about. It can’t be confined to mere technical criteria. You have to make the picture speak in your own language.

A CUT BY ANY OTHER NAME….

The first framing of this image included too much greenery on the right side, so it was cropped, then repositioned to make a “second” framing from the arched opening in the outer wall.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE WONDERFUL THING ABOUT COMPOSITION IN PHOTOGRAPHY is that you always, always, have a backup plan. What you don’t frame correctly in the actual shooting of an image can be corrected in post-editing cropping, the use of “framing” within the composition itself, or even how you finally matte the picture before hanging it on the wall. This is as it should be since many pictures are not so much born as re-imagined.

Once you frame a photo, you’re giving the viewer the first visual cue as to what to regard as important. If I included it, you should notice it. If I excluded it, it’s either to set loose your imagination on why I defined this world within these parameters, or because I, as the narrator, am telling you it just don’t matter. You can even further enhance the effectiveness of the frame by its shape. A rectangle might enforce the reading of information left-to-right, for example, while a square might force the eye toward dead center. The original framing is your own best call to action in a photograph.

And even after you’ve defined the frame, you can still add a second directive within it to hyper-focus attention in a very specific space. The use of arches, building overhangs, edges of windows, cliffs, shadows or other secondary “frames” provides even greater cues to the eye, and also adds an illusion of dimension and depth.

In the above shot, the old stone basilica is obviously the main feature of the image, and so was cropped from a wider original to eliminate distracting foreground shrubbery on the right. However, the arch through which the building is viewed was retained, to act as a “secondary frame” and as a way to illustrate scale. The first frame says what information is important, while the second frame makes sure we get to the heart of the image more efficiently.

Using all framing devices available in an image is like using caps, lower case and italicised letters in the same sentence. Composition is about yelling to get people over to your picture, then whispering, as you gently guide them toward its heart.

BOTH ENDS OF FREEDOM

Every camera ever manufactured can make this image, if the right person is behind it. It’s your eye that matters, not your toys.

A camera is a tool for learning how to see without a camera. —Dorothea Lange

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS A REAL DISCONNECT BETWEEN THE “FIRST CAMERAS” OF A GENERATION AGO and those of people just entering the art of photography today. Of course, individual experiences vary, but, in general, people born between 1950 and 1980 first snapped with devices that were decidedly limited as compared to the nearly limitless abilities of even basic gear today. And that creates a similar gap, across the eras, between what skills are native to one group versus the other.

To take one example, if your first camera, decades ago, was a simple box Brownie, the making of your pictures was pretty hamstrung. You had to purposefully labor to compensate for what your gear wouldn’t do. A deliberate plan had to be followed for every shot, since you couldn’t count on the camera to allow for, or correct, your mistakes. With a device that came hardwired with a single aperture, a shutter button, and not much else, you had to be mindful of a whole array of factors that could result in absolute failure. The idea of artistic “freedom” was sought first in knowledge, then, much later, in better equipment.

But if, on the other hand, you begin your photographic development with a camera that, in the present era, is almost miraculously flexible and responsive, freedom is a given. In a sense, it’s also a restraint of a different kind. That is, with bad gear, you’re a hero if you can wring any little bit of magic out of the process. But with equipment that can almost obey your every command, the old “I left the lens cap on”-type excuses are gone, along with any other reason you may offer for not getting at least average results. Thus the under-equipped and the over-equipped have two different missions: one must deliver despite his camera, while the other strives to deliver despite himself.

The entire gist of The Normal Eye is that I believe that even remarkable cameras (and the world is flooded with them) will betray the unseeing eye that mans them. Likewise, the trained eye will create miracles with anything handy. Our thrust here at TNE is toward teaching yourself the complete basics of photography as if you were actually constrained by limited equipment. At the point at which you’ve fully mastered the art of being better than your camera, then, and only then, is it time to get a new camera. Then learn to out-run that one, and so on.

The promise made by cameras today is the same promise that’s always been made by ever-advancing technology, that of wonderful results with minimum effort. It’s the photo equivalent of “eat whatever you want and still lose weight”. But it’s a false promise; photography only becomes art when we ask things of ourselves that our cameras cannot provide by themselves. Anything else is learning to accommodate mediocrity, a world of “pretty good”.

Which, inevitably, is never really good enough.

UNKNOWN KNOWNS

Everyone is visible, yet no one is known. Faceless crowds serve as shapes and props in a composition.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WE OFTEN WRITE IN THESE PAGES ABOUT PHOTOGRAPHY’S UNIQUE ABILITY to either reveal or conceal, and how we toggle between these two approaches, given the task at hand. Photographic images were originally recorded by using science to harness light, to increase its ability to illuminate life’s enveloping darkness, just as Edison did with the incandescent bulb. And in their attempt to master a completely new artistic medium, early photographers were constantly pushing that dark/light barrier, devising faster films and flash technology to show detail in the darkest, dimmest corners of life.

And when that battle was won, an amazing thing happened.

Photographers realized that completely escaping the dark also meant running away from mystery, from the subtlety of suggestion, from the unanswered questions residing within their pictures’ shadows. And from the earliest days of the 20th century, they began to selectively take away visual information, just as painters always had, teasing the imagination with what could not be seen.

Friendly chats or shadowy conspiracies? Your choice.

City scenes which feature individual faces in crowds opt for the drama (or boredom) written in the face of the everyday man. Their scowls at the noonday rush. Their worry at the train station. Their motives. But for an urban photographer, sometimes using shadow to swallow up facial details means being free to arrange people as objects, revealing no more about their inner dreams and drives than any other prop in an overall composition. This can be fun to play with, as some of the most unknowable people can reside in images taken in bright, public spaces. We see them, but we can’t know them.

Experimenting with the show it/hide it balance between people and their surroundings takes our photography beyond mere documentation, which is the first part of the journey from taking pictures to making them. Once we move from simple recording into interpretation, all the chains are off, and our images can really begin to breathe.

Share this:

April 16, 2016 | Categories: Available Light, Cities, Commentary, Composition, Conception | Tags: Abstraction, Composition, crowds, Shadows, silhouettes, Street Photography | 2 Comments