PARAMETERS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A PHOTOGRAPHER’S IMPACT IS ONLY PARTIALLY CREATED BY WHAT HE CHOOSES TO RECORD. That is, whatever his subject, be it banal or magnificent, his choice of what to shoot is only, at best, half of what makes or breaks his picture.

The other half of the miracle comes not from mastery of light, aperture, gear or conditions. It is in the frame, and what he includes or excludes from it. Landscape mode, portrait mode, big crop or little crop, the frame is the final determinant of how well the image argues for itself. The legendary director of photography for the New York Museum Of Modern Art, John Szarkowksi, expresses this idea for all time in his wonderful book The Photographer’s Eye:

To quote out of context is the essence of the photographer’s craft. The photograph’s edge defines content. The photographer edits the meanings and patterns of the world through an imaginary frame. This frame is the beginning of his picture’s geometry.

Consider, for a moment, the most vital, most inspiring images you’ve ever seen. Now imagine them cropped two inches wider, four inches to the left, five inches higher. The visual terms of engagement would be completely re-ordered. And what would be the result? Would you draw different conclusions, make different assumptions, experience a diminished ( or enhanced) sense of mystery?

The frame, and the choices the photographer makes in its design, is more decisive in the success of a picture than any other single factor. Technically imperfect photos become world-beaters every day simply because the frame is eloquent. And it also follows that a well-crafted bit of exposure can be dulled or blunted by a frame that is carelessly drawn.

The above image represents a choice, the drawing of a visual boundary. The top of the flowers and the objects surrounding the bucket aren’t missing because I shot too close, they’re deliberately excised because I made a deliberate decision that they didn’t add anything to the story I was trying to tell. You can disagree about whether I made the correct choice, but the making of that choice was as important (actually more important) than the subject itself.

Photographs have visual parameters, since we can’t make images big enough to include all of our experience. There are limits on the dimensions of what we show, and intelligent use of those boundaries can transform our work in marvelous ways.

SHOOT (AND THINK) BIG

The Nexus Of Resurrection, 2015. Image cropped from 4928 x 3264 pixels to 3550 x 1477, leaving enough density for a printable enlargement.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

BY NOW MOST OF US PROBABLY REALIZE THAT THERE IS NO REAL ADVANTAGE to “budgeting” shots in digital media the way we used to do in film. Harking back to the time of 24-exposure limits on one’s photographic fun, shooters maintained a running total in their heads of shots taken versus shots remaining, a cautious way of allocating frames on the fly, the idea being to finish the film roll and your tour stops at about the same time. Some kept notebooks; some doled out shots on a priority basis (one image of the waterfall, three of the ruins, four of the kids on the rides), and some, I suppose, were tempted to count on their fingers and/or toes. You had to be careful not to run out of frames.

Jump to the digital now, where we realize that, in all but the rarest cases, our shutter finger will crack and fall off before we “run out” of shots on even the most meager memory card. However, I still run into people who believe they are being prudent and providential by taking images at lower resolutions to “save space”, a false economy that is not only needless, but actually limits your options in the later process of editing.

Big files mean image density (lots o’ pixels) and therefore higher resolution. High resolution, in turn, means that you can crop substantial parts of a photo as needed and still have enough density for the image to hang together, even when printed out. Now, if you look at your work solely on a computer screen, protecting the integrity of a cropped image is less crucial, but if you’re lucky enough to create something you want to enlarge and frame, then you should begin with the fattest file you can get.

Review a few of your images that were, let’s say, less than compositionally sublime coming right out of the camera. Look at the pixel count on the same images after they were cropped to your liking. You’ll arrive at your own preference on what minimum resolution you’ll accept from the cropped versions. Thing is, the bigger you start, the more wiggle room you’ll have in editing.

As I say, most people already shoot at the largest file size possible. I merely send along this note to remind us all that we do it because it makes sense, and affords us real flexibility. It’s one of the amazing by-products of digital; we can, generally, shoot as much as we want for as long as we want.

TELL YOU WHAT’S BETTER….

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE AIM OF PHOTOGRAPHIC PROCESSING has shifted drastically in the post-digital age, and not necessarily in a good direction. Those of us old enough to remember mastadons, horse-drawn carriages and analog film were certainly aware that images could be edited or enhanced after the fact, conjuring up, say, memories of airbrush artists smoothing away chicken-pox scars from the shoulders of Miss January. We knew some of the magic happened in the lab.

Likewise, we knew that even the top masters did lots of tweaking in the darkroom prior to publication. The emphasis, however, was largely on perfecting an essentially strong picture, to make a good thing better/great. However, that emphasis is now placed, far too often, on trying to “save” images that were executed poorly in the first place, bringing marginal work up to some kind of baseline par of acceptability. That’s like the difference between polishing a Steinway and repainting a toy piano.

So, here’s my plea to those laboring to rescue their misbegotten babies in editing programs: Don’t repair. Re-shoot.

A good deal of the quick-fix buttons on editing programs should be marked with glowing red asterisks, with the following disclaimer at the bottom of the screen: WARNING: By using this change, you will fix your first proplem and create a different one somewhere else within your photograph. Let’s face it, no corrective action in editing happens in isolation. It must create a ripple effect, major or minor, in the final look of the image.

Use the “straighten” button for your misaligned shots, and they will lose sharpness. Suck out the darker shadows and your picture could lose dynamic range. Oversharpen your pictures and they will look harsh, with an unnatural transition between light and dark values. Reduce the noise in the image and it may appear flat, like pastel paint slathered on blotting paper.

Or here’s a radical notion: do all your thinking and planning before the shutter snaps. Yes, I know, I sound like some old schoolmarm scold, but please, can we at least consider the idea that there are no true shortcuts, that there can be no magical substitute for knowing your gear, developing an eye, and putting in the practice time required to make a photograph?

We once believed that patience was a virtue, that skill and mastery were more important than instant gratification. Know what? All of the greatest photographers still believe those things. And their work shows it.

TECHNIQUE OR STYLE?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YEARS OF WRITING DAILY HUMOR MATERIAL FOR OTHERS IN THE RADIO RACKET taught me that comedians fall into two general camps: those who say funny things and those who say things funny. Depending on how you rate writing, your own independence, or even your career longevity, you may opt to be in the first group, flawlessly executing pre-written material, or the second, where the manner in which you put things across allows you to get laughs reading the phone book.

I make this distinction between technique (the gag reciter) and style (the ability to imbue anything with comedy) because photographers must face the exact same choices. Technique helps us deliver the goods with technical precision, to master steps and procedures to correctly execute, say, a time exposure. Style is the ability to stamp our vision on nearly anything we see; it’s not about technical mastery, but internal development. Two different paths. Very different approaches to making pictures.

Obviously, great shooters can’t put their foot exclusively in either camp. Without technique, your work has no level standards or parameters. Lighting, exposure, composition….they all require skills that are as basic as a driver’s-ed class. However, if you merely learn how to do stuff, without having a guiding principle of how to harness those skills, your work will be devoid of a certain soul. Adept but not adorable. This is a trap I frequently find myself falling into, as my shots are a little technique heavy. Result: images that are scientifically sound but maybe a trifle soul-starved. Yeah, I could make this picture, but why did I?

On the style side, of course, you need fancy, whimsy, guts, and, yes, guesswork to produce a masterpiece. However, with an overabundance of unchanneled creativity, your work can become chaotic. Your narrative ability may not be up to the speed of your “vision”, or you may simply lack the wizardry to capture what your eye is seeing. Photographers are, more than anything else, storytellers. If they fail in either grammar or imagination, the whole thing is noise.

Like comics, photographers are both technicians and artists. Even the most seasoned among us needs a touch o’ the geek and a touch of the poet. Anything else is low comedy.

ONE STORY AT A TIME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

BEING A MULTI-TASKER IS NO LONGER A MATTER OF CHOICE. We love to pretend that we’re adept at turning off selective parts of the hurricane of sensory input that comprises the whole of our daily life, but, fact is, we cannnot. You might be able to do as few as three things at a time in this world, but only if you struggle against a constant cacophony of sensations.

Unfortunately, creating art sometimes requires quiet, clarity, the ability to edit out unwanted sights and sounds in order to find a clear path toward a coherent vision. And this impacts photography as well as any other creative enterprise.

Urban life presents an especially big challenge to this urge to “get clear”, to untangle conflicting stories and draw out clean, direct messages for our images. Major cities are like 24-hour whistle factories, with thousands of things screaming for our attention. Thing is, there just isn’t enough attention to go around. Often, in poring over old projects, we find that a fourth, a third, even half of the information in a picture can be extracted in the editing process and still leave more than enough data to get our point across. And herein lies a problem.

If it’s getting harder and harder to edit in the moment to boil a photograph down to its essence, the editing phase becomes more crucial than ever before. You either get the best picture in the taking or in the remaking. It can be argued that practice helps the photographer learn to quickly ferret out simple stories within a mass of visual noise, and, of course, the more you shoot, the more you learn what not to shoot. But it seems inevitable that editing, and re-editing, will become a bigger part of the overall task of making pictures.

If the weakest of your photographic skills is post-processing, you might strongly consider upping that particular part of your game. The world isn’t slowing down anytime soon. It’s great to know, in an instant, how to make a strong image. But, as my dad always said, that’s why God put erasers on pencils. Editing can be where acceptable pictures buff up into contenders.

TEMPORARILY ACTUAL

It’s the truth. It’s actual. Everything is satisfactual. –lyrics from the Oscar-winning song Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY WAS ERRONEOUSLY BILLED, EARLY IN ITS DEVELOPMENT, as a mere recording of reality. This was, of course, an attempt to characterize the picture-making process as more bloodless, less artistic than painting, which was an interpretation of the world. What early haters of the camera failed to realize, of course, was that photographers were just as selective in their depiction of life as painters, since their medium too, was an interpretation…..of isolated moments, of preferred angles, of temporary actuality.

If you look at individual frames within a strip of motion picture film, it becomes perfectly clear that each still image is a self-contained world, with no way to intuit what has come before a given moment nor what will come next. Thus, no one frame is “reality” but a select sample of it. In daily photography, our choice of angle, approach, and especially light can allow us to create an infinite number of “realities” that only exist in the precise moment in which we see and freeze them.

Let’s look specifically at light. As it’s jumbled in multiple reflections, light is particularly precious to the photographer’s eye, since a captured image may recall an effect that even people within inches of the shooter could not see. In the above photo, for example, this mosaic of reflections inside the vestibule of a high-ceilinged building was visible from several specific positions in the foyer. Move yourself three feet either way, however, and this pattern could not be seen at all. In other words, this photographic “reality” came briefly into existence under the most controlled conditions, then was gone.

John Szarkowski, the legendary director of photography for the New York Museum of Modern Art, dedicates an entire section of his essential book The Photographer’s Eye to what he calls “Vantage Point” and its importance to a mastery of the medium. “Pictures (can) reveal not only the clarity but the obscurity of things…and these mysterious and evasive images can also, in their own terms, seem ordered and meaningful.”

Photography is about viewing all of reality and extracting little jewels from within it.

That’s not mere recording.

That’s creation.

FINDING AN OPENING

Walking briskly down a city street with wildly varying light conditions, you might not want to stop to fully calculate manual exposure before every shot. In such cases, Aperture Priority may be good fit.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I KNOW THAT I APPROACH THE IDEA OF SHOOTING ON MANUAL with what must strike some as evangelistic zeal. We’re talking full-on-John-The-Baptist-mad-prophet mode. I do so because I believe that, the further you can go toward overseeing every single facet of your picture taking, that is, the less you delegate to a machine that can’t think, the better. Generally. Most of the time. Almost always.

Except sometimes.

Aperture Priority, the mode that I most agree with after pure manual, can be very valuable in specific conditions, for very specific reasons. In AP (Av for Canon folks), you dial in the aperture you want for everything you’re about to shoot, depending on what depth-of-field you want as a constant. Then it’s the camera’s job to work around you, adjusting the shutter speed to more or less guarantee a proper exposure. Let me interject here that there are millions of great photographers who nearly live on the AP setting, and, like any other strategy, you have to decide whether it will deliver the goods as you define them.

If you are “running and gunning”, that is, shooting a lot of frames quickly, where your light conditions, shot-to-shot, will be changing a great deal, Aperture Priority might keep you from tearing out your hair by eliminating the extra time you’d spend custom-calculating shutter speed in full manual mode. Fashion, news and sports situations are obviously instances where you need to be fully mindful of your composition, cases in which those extra fragments of “figgerin'” time in between clicks might make you miss an opportunity. And no one will have to tell you when you’re in such a situation.

Conversely, if you are shooting more or less at leisure, with time to strategize in-between shots, or with uniform light conditions from one frame to the next, then full manual may work for you. I have shot in manual for so many years that, in all but the most hectic conditions (cattle stampede or worse), I’m fast enough to get what I want even with calculation time factored in. But it doesn’t matter what works for me, does it, since I won’t be taking your pictures (pause here to thank your lucky stars). If you need one less task to hassle with, and AP gives you that one extra smidge of comfort, mazel tov.

One other thing to note about Aperture Priority: it’s not foolproof. Change your central focal spot to different objects within the same composition (say from a tree to the rock next to the tree) snap several frames, and the exposure could be vastly different on each image. Could that happen when you’re on manual? Certainly. You can, of course, fiddle with exposure compensation on AP, essentially overruling the camera, but, to take the time for all that, you’re really not saving much more time than shooting manual anyway. See what you can live with and go.

This blog is a forum, not the Ten Commandments, so I never want to profess that my way is the only way, whether it’s taking photographs or deciding what toppings should go on pizzas. Although, let’s face it, people who put pineapple on them….that’s just warped, am I right?

A GAME OF INCHES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS PROGRESS FROM WHAT I CALL SNAPSHOT MENTALITY TO “CONTACT SHEET” MENTALITY as we move from eager beginners to seasoned shooters. Many of the transitional behaviors are familiar: we actually learn what our cameras can do, we begin to pre-visualize shots, we avoid 9 out of the 10 most common errors, etc. However, one of the vestiges of snapshot mentality that lingers a while is the tendency to “settle”, to be, in effect, grateful that our snap resulted in any kind of a shot, then moving too quickly on to the next subject. It’s a little like marrying the first boy that ever asked you out, and it can prevent your hanging around long enough to go beyond getting “a” shot to land “the” shot.

In snapshot mentality, we’re grateful we got anything. Oh, good, it came out. In contact sheet mentality, we look for as many ways to visualize something as possible, like the film guys who shot ten rolls to get three pictures, seeing all their possibilities laid side-by-side on a contact sheet. The film guys stood in the batter’s box long enough to make a home run out one of all those pitched balls. With the snapshot guy, however, it’s make-or-break on a single take. I don’t like the odds. My corollary to the adage always be shooting would be always shoot more.

All of which is to plead with you to please, please over-shoot, especially with dynamic light conditions that can change dramatically from second to second. In the shot at the top, I was contending with speedily rolling overcast, the kind of sun-clouds-sun rotation that happens when a brief rain shower rolls through. My story was simply: it’s early morning and it just rained. This first shot got these basics across, and, if I were thinking like a snapshot photographer, I would have rejoiced that I nailed the composition and quit while I was ahead. However, something told me to wait, and sure enough, a brighter patch of sunshine, just a minute later, gave me a color boost that popped the page much more effectively. Same settings, same composition. The one variable: the patience to play what is, for shooters, a game of inches. A small difference. But a difference, nonetheless.

And that’s what these little blurbs are. Not examples of groundbreaking art, just illustrations of the different ways to approach a problem. Digital shooting is cheap shooting, nearly free most of the time. Shouldn’t we, then, give ourselves at least as many editing choices as film guys who shot rolls of “maybes” at great expense, in search of their “yeses”? Hmm?

THE ABCs OF TMI

This street shot from a park in lower Manhattan is not ready for prime time, but it might get there with creative cropping.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR ME, ONE OF THE GREATEST ANCILLARY BENEFITS of doing historical research has been the privilege of poring over old files of newspaper and magazine photographs, in many cases viewing original, pre-publication master shots. It’s truly an exercise in reading between the “lines”, those hurried slashes of white grease pencil applied by editors as cropping instructions on shots that were too big, too busy, too slow in getting to the point. In many cases, you realize that, while the photographer may have taken the picture, it was the editor who found the picture.

Of course, no amount of cutting can improve a shot if there is not already a core story hiding within it. You can pare away the skin and seed of an apple, but some apples prove themselves rotten through and through. It’s the same with a photograph. However, if you teach yourself how to spot what, within a frame, is fighting with the central strength of a photo, it becomes obvious where to wield your scissors.

In the master shot image at top, the symmetry of the left and right groups of park visitors is blunted in its effect by the unneeded information along the top and bottom thirds of the frame. The shot is not really about the museum in the distance nor the ground in front of the benches. They just don’t help the flow of the picture, so losing them seems like the easiest way to boost the overall composition.

Now the shot is essentially a wide-angle, and, absent the earlier distractions, a kind of horseshoe curve emerges, tying the two benches together. You might even think of it as an arch shape, with the walking woman at the top acting as a keystone. She now draws attention first to the center, then around the curve, so that getting people to see what I am seeing becomes a lot easier. Finally, there is still a very loud distraction from the color in the shot, so a black-and-white remix keeps the reds and louder colors from “showing off” and lessening the impact of the story. The final result is still no masterpiece, but it does demonstrate that there was a very different picture hiding within the master shot, one that was certainly worth going after.

One of the downsides of being an amateur shooter is not reaping the benefit of a ruthless photo editor. However, learning to spot the weaknesses in potentially effective shots can be learned, most importantly the “ruthless” part. If you believe in an image, you won’t shy away from trimming its fingernails a bit to give it a chance to shine.

LESS STILL, MORE LIFE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHIC HISTORIANS WILL PROBABLY CRINGE AT MY OVER-SIMPLIFICATION, but I tend to believe that still-life compositions were originally popular to shooters because they solved a technical problem. At the dawn of the imaging art, recording media, from salted paper to glass plates, were so abysmally slow that exposure times stretched, in some cases, to nearly an hour. This meant that subject matter with any kinetic quality, from evolving landscapes to a baby’s face, were rendered poorly compared to inanimate objects. Still lifes were not so much about the beauty and color of fruit and cheese on a plate as they were about practicing…learning how to harness light and deliver a desired effect.

As film and lenses both sped up, a still life could be chosen purely on its aesthetic appeal, but the emphasis was still on generating a “realistic” image…an imitation of life. The 20th century cured both photography and painting of that narrow view, and now a still life, at least to me, offers the chance to transform mundane material, to force the viewer to re-imagine it. You can do this with various processes and approaches, but the main appeal to me is the chance to toss the object out of its native context and allow it to be anything…or nothing.

In the image at left, the home-grown vegetables, seen in their most natural state, actually have become alien to our pre-packaged notions of nutrition. They don’t even look like what arrives at many “organic” markets, much less the estranged end-product from Green Giant or Freshlike. And so we are nearly able to see these vegetables as something else. Weeds? Flowers? Decay? Design? Photographing them in our own way, we are free to assign nearly any quality to them. They might, for example, be suggestive of a floral bouquet, a far cry from the edibles we think we know. Still life compositions can startle when they are less “still” and more “life”, but we have to get away from our subjects and approach them around their blind side.

As always, it’s not what we see, but how.

THE TAKEAWAY

The girl bathed in ceiling light is a nice start, but this picture needs some help to get where it’s going.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT IS SAID THAT THE GODDESS ATHENA WAS BORN, FULLY GROWN AND ARMORED, out of the forehead of Zeus. Other than being the only case where a man experienced anything that approached labor pain, the story always reminds me that ideas rarely arrive in their final form, especially in photography. If Athena had a Leica, she probably could have taken perfect shots without needing to compose or plan. We mere mortals are forced to either (a) report to hate-crazed photo editors, or (b) learn how to crop.

Many shots are created in stages, and there’s no shame in the game, since our original conception undergoes many phases from the first spark to something we’d actually hang on a wall. Creation itself is a process, which is why photographers should actually embrace the stages their work will pass through. The more thought that is applied to making an image, the better chance that the best way of doing something will reveal itself. Of course, it can also reveal the fact that there is nothing really to work with, in which case, hey, the bar should be open now, let’s go lick our wounds.

The original shot shown above is not yet a good photograph, but a good beginning for a  photograph. The lady bathed in light seems certainly to have been pre-selected to be the focal point of the picture, but there are way too many competing elements around her, robbing her of the prominence she deserves in the final frame. So let’s get after it.

photograph. The lady bathed in light seems certainly to have been pre-selected to be the focal point of the picture, but there are way too many competing elements around her, robbing her of the prominence she deserves in the final frame. So let’s get after it.

First, none of the information on the left side of the frame makes it any clearer that she’s alone or that she’s on the second floor of the building. We can make that plain with half the acreage, so snip. Similarly, the guys in shadow to her right aren’t part of the story we are crafting for her. If she’s isolated, let’s make her isolated and be unmistakable about it. She’s “apart” already from the sea of people below her. She’s geographically and physically separated from them, but the extra guys make the argument weaker, so, snip, away they go.

Finally, the entire upper-floor/lower-floor line of sight will be accentuated if we crop for a portrait orientation and move the frame so she is on the upper-right-hand corner of it. It forces the eye to discover the story of the picture vertically, so snip and we’re done.

So, at the end, we did not make any changes via processing, only the old scissors. Taking things away, not adding them on, actually made the picture work better. Fate gave me the girl and the wonderful light she was bathed in, but there was work to do. She didn’t arrive, ready to party, like Athena, but she’s a little closer to goddess status after some adjustment.

GOING NEGATIVE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I got plenty of nothin’, and nothin’s plenty for me. —Ira Gershwin, Porgy and Bess

I BELIEVE THAT MANY PHOTOGRAPHS ARE IMPROVED BY THE SIMPLEST OF MATH OPERATIONS: addition and subtraction. Look at nearly any image you’ve created that “worked” and you can see that there is not one more thing in the image than there needs to be. Something told you to either supply or eliminate elements in the composition until the impact of the picture was maximized. Realizing the reverse effect is pretty easy as well, although not as much fun. If there is one tree too many or one object too few in the frame, you can sense the imbalance in your near-miss pictures. And man, does that hurt.

We used to refer to open areas of a picture as “blank” space, and were often talked out of using it at all by various A-B-C composition tutorials that told us that large expanses of sky could kill a good landscape. Today, we refer to this unused real estate as “negative” space, but we are now more inclined to see it as well, a positive thing. The take-home from this is, simply, that no technique should be universally ruled out, or ruled in, for every image. Truth is, there are times when not filling the frame with stuff, or selectively making use of negative space boosts the wattage of what you’re trying to say.

We used to refer to open areas of a picture as “blank” space, and were often talked out of using it at all by various A-B-C composition tutorials that told us that large expanses of sky could kill a good landscape. Today, we refer to this unused real estate as “negative” space, but we are now more inclined to see it as well, a positive thing. The take-home from this is, simply, that no technique should be universally ruled out, or ruled in, for every image. Truth is, there are times when not filling the frame with stuff, or selectively making use of negative space boosts the wattage of what you’re trying to say.

Instead of “negative” space, I prefer the term “secondary space”, since what you’re really doing is mapping your pictures into zones of the things that should be of primary interest and those that should complement those things without competing with them. Landscapes are the easiest way to demonstrate this. In the image at left, I wanted to accentuate the distance between the foreground tree and the background mountain. Framing the two elements to merely overlap gave no sense of space, and, in color, actually made the photo busy and hard to read. There seemed to be no primary object in the frame. Composing so that some sky intervened to the right of the tree and the top of the mountain re-established the sense of distance and kept the textures of both objects from fighting with each other.

Secondary space need not be empty. It can take the form of a texture, be it a body of water, cloud formations, a flooring pattern, or a stone wall. The idea is to use the space to support, but never upstage the primary space. Sometimes what you need to complete an image is nothing. You just have to stick the nothing in the right place.

THE FLOATING 50

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU CANNOT BECOME A GREAT PHOTOGRAPHER WITHOUT BEING YOUR OWN BEST EDITOR, no matter how brilliant or instinctual your shooter’s eye may be. Art is both addition and subtraction, and the image frame is about both inclusion and exclusion. You get your viewers’ attention by knowing what to show. You hold that attention, and burn your images into their minds, by learning what to pare away.

I’ve written several variations on this theme, so the best way to restate it is in the voice of the truly visionary godfather of street photography, Henri Cartier-Bresson. Ironically, this master of in-camera composition (he is reputed never to have cropped a single shot after it was taken) was nonetheless remarkably aware of what most of us must do to improve an image through post-editing:

This recognition, in real life, of a rhythm of surfaces, lines, and values is for me the essence of photography; composition should be a constant of preoccupation, being a simultaneous coalition – an organic coordination of visual elements. We must avoid snapping away, shooting quickly and without thought, overloading ourselves with unnecessary images that clutter our memory and diminish the clarity of the whole.

Insert whatever is French for “Amen” here.

I often find that up to 50% of some of my original shots can later be excised without doing any harm to the core of the photograph, and that, in many cases, actually improving them. Does that mean that my original concept was wrong? Not so much, although there are times when that’s absolutely true. The daunting thing is that the 50% floats around. Sometimes you need to cut the fat in the edges: other times the dead center of the shot is flabby. Sometimes the 50 is aggregate, with 25% trimmed from two different areas of the overall composition.

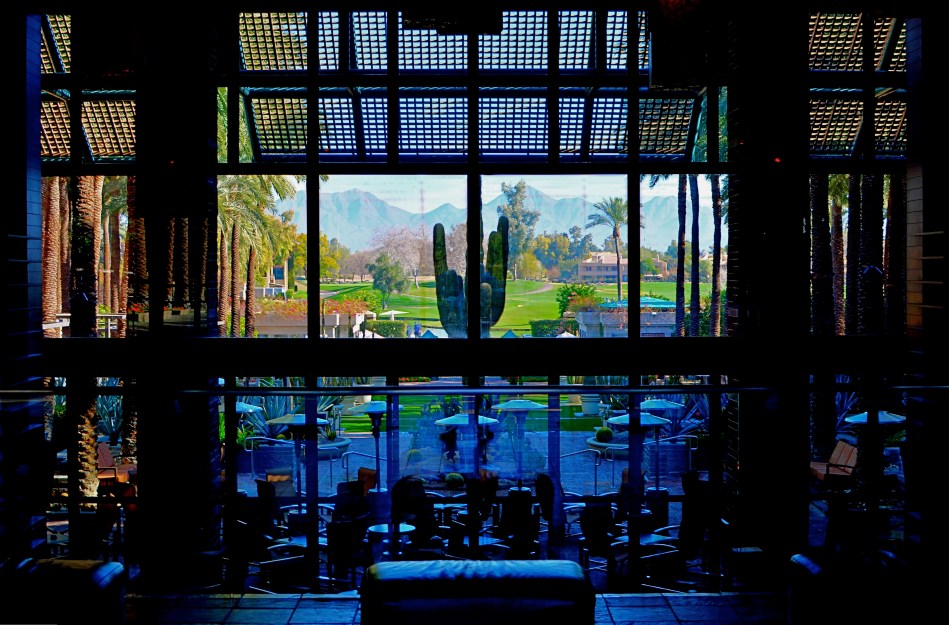

On occasion, as with the above picture (see the original off to the left), the entire bottom half of the shot drags down the top. In the cropped shot, the long lateral line between indoors and outdoors is much more unbroken, making for a more “readable” shot from left to right. The disappearance of the dark furniture at the bottom of the master shot creates no problems, and actually solves a few. Do a disciplined search of the nobler near-misses in your own work and see how many floating 50’s you discover. Freeing your shots of the things that “clutter our memory and diminish the clarity of the whole” is humbling, but it’s also a revelation.

IF HUE GO AWAY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT SEEMS UNGRACIOUS FOR A PHOTOGRAPHER TO COMPLAIN ABOUT AN OVER-ABUNDANCE OF LIGHT, since that’s basically the currency we trade in. More typically we gripe about not being able to bring enough of the stuff into a shot. I mean, the entire history of the medium is one big let-there-be-more-light prayer. But that’s not to say that light can’t create annoyance when you’re in a place where there is glorious, radiant illumination of….acres of nothing.

I’m not talking about sunlight on endless expanses of starched plain. I refer here to subject matter that is so uninteresting that, even though a bumptious bounty of light is drenching everything in sight, there is nothing to make a photograph of. Nothing that compels, inspires, jars or even registers. I recently made my annual return to a festival that, due to my frequent farming of it over the years, has now bottomed out visually. There is nothing left to say about it, although all that “nothing” is stunningly lit at this time of year.

In fact, it’s only by shooting just abstracted shapes, shades and rays, rather than recognizable subjects, that I was able to create any composition even worth staying awake for, and then only by using extremely sharp contrast and eliminating color completely. To me, the only thing more pointless than lousy subject matter is beautiful looking lousy subject matter, saturated in golden hues, but signifying nothing. Kinda the George Hamilton of photos.

So the plan became, simply, to turn my back on the bright balloons, food booths, passing parade of people and spring scenery that, in earlier years, I would have been happy to capture, and instead render arrangements without any narrative meaning, just whatever impact could be seen using light as nearly the lone element. In the above picture, I did relent in keeping the silhouetted couple in the final picture, so that it’s not as “cold” as originally conceived, but otherwise it’s a pretty stark image. Photography without light is impossible, but we also have to refuse to take light “as is” from time to time, to do our best to orchestrate it, much as we would vary shadings with pencil or crayon. We know that the camera loves light, but it’s still our job to tell it where, and how, to look.

SQUARE STORIES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

BETTER PHOTO HISTORIANS THAN ME WOULD BE ABLE to pinpoint the precise moment in time when the landscape-sized image first eclipsed the square image for most photo shooters. I’d tackle the search myself, but it’s late, and I’m about a martini and a half too far into relax mode, so there it is. But, regardless of the exact instant it first began to wane, the square is back, and bigger than ever, its refreshed use as a distinct mode of composition greeted like a revelation, rather than a return. Cool beans.

The unilateral quadrangle (I get wordy when I drink) managed to barely survive on the periphery of photography, even as the square-centric Polaroid print nearly wobbled out of existence, then came back, as hipsters in the lo-fi movement revived the use of instant print cameras. Then cel phones began offering a pre-selectable square setting for their cameras, and that became a thing. But the biggest boost for the square’s comeback came with a thing called Instagram. You may have heard about this quaint little app. I understand the developers made a few bucks on it.

Still, we are pretty universally conditioned to envision pictures in either “landscape” or (flip this up on its side) “portrait” modes, so much so that director Wes Anderson garnered as much press for his use of the old anamorphic aspect ratio in The Grand Budapest Hotel as he did for the movie’s content. Strangely, the square-format photograph is, upon its return, a bit of a retro novelty.

Composing a shot in roughly 1/3 less space than a landscape frame is a challenge, simply because we have fallen out of the habit for a few decades, but it does have a certain elegance. Lately, I have tried to use the square to effectively tell stories that I traditionally saw in vast or wide scenarios. Construction projects are one such case, in that they seem to call for wide angles and far reaching vistas, what we might call scope. The above image is my attempt to express most of what goes into a building project in what some would call cramped quarters. The main story elements, that is, the action, the range of tone, the compositional depth, are all present, but confined within the quadrangle. Of course, with a DSLR, I can’t start with a square, but I can envision where in the shot the best square is, and crop to it in post-processing.

Composing for a given dimension is a discipline, and, as such, it is valuable as a practice tool, since photographers should always be visualizing every possible way to get their story told. The square may be a prison. But it also may be an answer. The end result is what matters most.

MORE THAN FOOD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU COULD ARGUE ALL DAY ABOUT WHETHER PUBLIC SPACES POSSESS MORE VISUAL POTENTIAL when they are full or when they are dead empty, and, depending on your photographic approach, both arguments would be correct. In other words, instead of a hard-and-fast truth, you have multiple truths, depending on which space is shot by which photographer under such-and-such circumstances. Hey, if ya want a vague premise, I’m your boy.

Plazas, train platforms, museums, places of worship, restaurants, sports arenas…..all the places where people convene in big mobs have all produced stunning images taken when said places contain no people at all. After hours, before opening, last call, snow days…there are endless reasons why people don’t go to places, and the unfilled space created by their absence is a separate kind of compositional challenge.

I have stated in previous posts on this forum that, for me, museums are tremendous sources of negative space, and yet positive possibilities,when devoid of crowds. Maybe it’s when people are about to be somewhere, when something is nearly ready to happen, that public places possess a certain, well, suspense. Whatever the phenomenon, I feel it, and will always squeeze off a few shots while the moment lasts.

Similarly, eateries are both potentially joyful and potentially lonely, and that kind of uncertainty excites me as a photographer. But you may be on the opposite side of the discussion. I can certainly understand that some would see a bunch of empty tables and chairs as depressing, unmistakably desolate. But I think it depends on the photograph, and I think it always will. There are many images of two people seated together at a cafe who are, sadly, miles apart due to their estrangement, and there are an equal number of pics of a hall just before celebrants from a wedding stream in. As with so much in photography, feeling comes both from what you did and didn’t show.

SHADOWS AS STAGERS

The idea of this image is to highlight what lies beyond the window framing, not the objects in front of it. Lighting should serve that end.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THOSE WHO ADHERE TO THE CLASSIC “RULE OF THIRDS” system of composition often suggest that you imagine your frame with a nine-space grid super-imposed over it, the better to help you place your subject in the greatest place of visual interest. This place is usually at the intersection of several of these grid lines, and, whether or not you strictly adhere to the “thirds” system, it’s useful to compose your shots purposefully, and the grid does give you a kind of subliminal habit of doing just that.

Sometimes, however, I find that the invisible grid can be rendered briefly visible to become a real part of your composition. That is to say, framing through silhouetted patterns can add a little dimension to an otherwise flat image. Leaving some foreground elements deliberately underlit is kind of a double win, in that it eliminates detail that might read as clutter, and helps hem in the parts of the background items you want to most highlight.

These days, with HDR and other facile post-production fixes multiplying like rabbits on Viagra, the trend has been to recover as much detail from darker elements as possible. However, this effect of everything being magically “lit” at one even level can be a little jarring since it clearly runs counter to the way we truly see. It’s great for novel or fantasy shots, but the good old-fashioned silhouette is the most elemental way to add the perception of depth to a scene as well as steering attention wherever you need it. Shadows can set the stage for certain images in a dramatic fashion.

Cheap. Fast. Easy. Repeat.

COME EARLY / STAY LATE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PUBLIC SPACES OFTEN LOSE THEIR POWER AS GRAND DESIGNS once they actually are occupied by the public. If you have ever leafed through books of architectural renderings, the original drawings for squares, plazas, office buildings or other mass gathering places, the elegance of their patterns is apparent in a way that they cease to be, once they are teeming with commuters or customers.

This doesn’t mean that humans “spoil” the art of architecture, however, the overlay of drama and tension created by the presence of huge hordes of people definitely distracts from an appreciation of the beauty that is so clean and clear in a place’s sketch phase. Photographically, people as design objects tend to steal the scene, if you will, making public settings less dramatic in some ways. That’s why I like to make images of such locales when they are essentially empty, since it forces the eye to see design as the dominant story in the picture. I suppose that I’m channeling the great designers and illustrators that influenced me as a young would-be comic book artist. It’s a matter of emphasis. While other kids worked on rendering their superheroes’ muscles and capes correctly, I wanted to draw Metropolis right.

I recently began driving to various mega-resorts in the Phoenix, Arizona area to capture scenes in either early morning or late afternoon. Some are grand in their ambition, and more than a few are plain over-the-top vulgar, but sometimes I find that just working with the buildings and landscaping as a designer might have originally imagined them can be surprising. Taking places which were meant to accommodate large gatherings of people, then extracting said people, forces the eye to align itself with the original designer’s idea without compromise. Try it, and you may also find that coming early or staying late at a public area gives you a different photographic perspective on a site. At any rate, it’s another exercise in re-seeing, or forcing yourself to visualize a familiar thing eccentrically.

THE CENTER HOLDS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST FASCINATING PARTS OF THE LEGEND of Henri Cartier-Bresson, the artist who is the world’s model for street photography, is the oft-repeated story that he never cropped a shot over the many decades of his remarkable career. Thus the man who originated the phrase “the decisive moment” to indicate that there was but one ideal instant to capture something perfectly in the camera is also credited with creating flawless on-the-spot compositions, image after image, year after year. Yeah, well….

I love HCB, and I personally can’t find a single one of his images that I could improve upon, no matter where I was to wield my magic scissors. But just as the writer in me believes that great novels aren’t written, but re-written, I believe that many great photo compositions emerge after much additional consideration, long after the shutter snaps. It’s not that one shouldn’t strive to get things as perfect as possible in the moment. In fact, there is overwhelming evidence that many photographers do exactly that, nearly all the time.

It’s that “nearly”, however, that describes most photos, something which might be converted to “definitely” in the cropping process. In fact, I am starting to feel that the very first thing to be done with a picture in post-production is to just start paring away, only stopping when the center of the idea has been reached. It’s gut-wrenching, since we usually fall in love with our pictures at first sight (and in their first versions). But even if God decided to make one of us, say Cartier-Bresson, the messenger of his divine eye, he certainly didn’t make that trait as common as, say, green eyes or freckles. For most of us, most of the time, we need to eliminate everything that diverts the eye anywhere but where the main message is. As an example, the hammock image above is the result of cutting away nearly 2/3 of the original photograph.

There are a few times when an image comes full-born out of the camera, all muscle and no fat. However, in the digital age, re-thinking one’s realization of a concept is easier than it’s ever been, and there is no downside to doing so. If there is a narrative ground-zero to your photo, don’t worry. The center will hold.

FRAGMENTS AND SHARDS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

GLASS SURFACES REPRESENT A SERIES OF CHOICES FOR PHOTOGRAPHERS, an endless variety of effects based on the fact that they are both windows and mirrors, bouncing, amplifying or channeling light no less than any other subject in your frame. No two shooters approach the use (or avoidance) of glass as a compositional component in quite the same way. To some, it’s a barrier that they have to get past to present a clear view of their subject. To others, its fragments and shards of angle and light are part of the picture, adding their own commentary or irony.

I usually judge glass’ value in a photograph by two basic qualifiers: context and structure. First, context: suppose you are focused on something that lies just beyond a storefront window. What visual information is outside the scope of the viewer, say something over your shoulder or across the street, that might provide additional impact or context if reflected in the glass that is in direct view? It goes without saying that all reflections are not equal, so automatically factoring them into your photo may add dimension, or merely clutter things up.

The other qualifier is the structure of the glass itself. How does the glass break up, distort, or re-color light within an enclosure? In the above image, for example, I was fascinated by the complex patterns of glass in an auto showroom, especially in the way it reassigned hues once the sun began to set. I had a lot of golden light fighting for dominance with the darker colors of the lit surfaces within the building, making for a kind of cubist effect. No color was trustworthy or natural , and yet everything could be rendered “as is” and regarded by the eye as “real”. The glass was part of the composition, in this instance, and at this precise moment. Midday or morning light would render a completely different effect, perhaps an unwelcome one.

Great artists from Eugene Atget to Robert Frank have created compelling images using glass as a kind character actor in their shots. It’s an easy way to deepen the impact of your shots. Let the shards and fragments act like tiles to assemble your own mosaics.