THE ABCs OF A.B.S.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THIS IS THE TIME OF YEAR, IN THE DAYS OF FILM, WHEN THE EASTMAN KODAK COMPANY used to see a predictable surge in their annual sales, all tied to our ties to our loved ones. Each holiday season, the world’s biggest manufacturer of film reminded us that cameras were not only a great gift idea, they were the most important thing to be found under our respective Christmas trees. Their tremendously successful “Open Me First” ad campaign said it all: we couldn’t begin to truly experience all that family-centric holiday joy without a Kodak camera on hand to capture every giggle of surprise. The message was: shoot a lot of film. And if that doesn’t perfectly capture the perfect season, shoot more.

Ironically, it was the near death of film that finally freed us up from the single biggest constraint on our photographic freedom, that being the constraint of cost. Digital media, and the ease and ubiquity of cameras of all price points finally have freed the non-pros and the non-rich, making the admonition Always Be Shooting much more irresistibly urgent. We can afford miscalculations. We can afford do-overs. We can fix our worst mistakes without converting a hall bathroom into Dad’s Wide, Weird World Of Chemicals. We can gradually develop a concept over many “takes”, and we can salvage more of those visions. We can win more often.

The great photographer Ernest Haas once exhorted his students to “look for the ‘a-ha’ moment”, which meant not to be content with the first, or even the fifth framing of an idea in your viewfinder (okay, display screen). Asked in a lecture what the best wide-angle lens was, he quipped “two steps backward”, meaning that your best solution to a so-called technical problem is actually within yourself. Change your view, and change the outcome. The shot at the top of this post, as one example, only came at the end of ten other attempts at the same scene, all shot within a few minutes’ time. In the days of film, I would have had to settle for a much earlier version. I simply wouldn’t have kept clicking long enough to realize what I wanted from the subject.

Always Be Shooting doesn’t mean just clicking away madly, hoping that a jewel will magically emerge from a random batch of frames. It means keeping yourself in seeking mode long enough for ideas to emerge, then shooting beyond that to get those ideas right. Film made it possible to all of us to dream of capturing great memories. But it is the end of film that makes it possible for us to refine more of those memories before all those fleeting smiles have a chance to fade out of our reach.

ON THE SOFT SIDE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE WORLD’S FIRST MOVIE STUDIO WAS A TARPAPER SHACK ON A TURNTABLE. Dubbed by Thomas Edison’s techies as “The Black Maria” (as ambulances were grimly named back at the time), the structure rotated to take advantage of wherever sunlight was available in the California sky, thus allowing the film crew to extend its daily shooting schedule by more than half in the era of extremely slow film stocks. Eventually artificial light of sufficient strength was developed for the movies, and actors no longer had to brave motion sickness just to rescue fair damsels. So it goes.

More than a century hence, some photographers actually have to be reminded to use natural light, specifically window light, as a better alternative to studio lights or flash units. Certainly anyone who has shot portraits for a while has already learned that window light is softer and more diffuse than anything you can plug in, thus making it far more flattering to faces (as well as forgiving of , er, flaws). It’s also good to remember that it can lend a warming effect to an entire room, on those occasions where the room itself is a kind of still life subject.

Your window light source can be harsher if the sun is arching over the roof of your building toward the window (east to west), so a window that receives light at a right angle from the crossing sun is better, since it’s already been buffered a bit. This also allows you to expose so that the details outside the window (trees, scenery, etc.) aren’t blown out, assuming that you want them to be prominent in the picture. For inside the window, set your initial exposure for the brightest objects inside the room. If they aren’t white-hot, there is less severe contrast between light and dark objects, and the shot looks more balanced.

I like a look that suggests that just enough light has crept into the room to gently illuminate everything in it from front to back. You’ll have to arrive at your own preferred look, deciding how much, if any, of the light you want to “drop off” to drape selective parts of the frame in shadow. Your vision, your choice. Point is, natural light is so wonderfully workable for a variety of looks that, once you start to develop your use of it, you might reach for artificial light less and less.

Turns out, that Edison guy was pretty clever.

RAMPING UP

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN THE IMAGINARY PHOTOGRAPHY BOOKSHELF OF MY MIND THERE ARE HUNDREDS OF VOLUMES that speak of nothing else except the exquisite light of early morning, the so-called “golden hour” in which a certain rich warmth bathes all. You’ve read endless articles and posts on this as well, so nothing I can cite about the science or aesthetic aspects of it can add much. However, I think that there is a secondary benefit to shooting early in the day, and it speaks to human rhythm, a factor which creates opportunities for imaging every bit as vital as the quality of available light.

Cities and communities don’t jolt awake in one surge: they gently creep into life, with streets gradually taking on the staging that will define that day. The first signs could be the winking on of lights, or the slow, quiet shuffle of the first shift of cleaners, washers, trimmers and delivery workers. First light brings the photographer a special relationship with the world, as he/she has a very private audience with all the gears that will soon whirr and buzz into the overall noise of the day. You are witness to a different heartbeat of life, and the quieter pace informs your shooting choices, seeping into you in small increments like a light morning dew. You are almost literally forced to move slower, to think more deliberately, and that state always makes for better picture making.

Some atmospheres, like libraries or churches, retain this feel throughout the entire day, imposing a mood of silence (or at least contemplation) that is also conducive to a better thought process for photography, but in most settings, as the day wears on, the magic wears off. Early day is a distinctly different day from the one you’ll experience after 9am. It isn’t merely about light, and, once you learn to re-tune your inner radio for it, you can find yourself going back for more.

This is no mere poetic dreaminess. The more nuances you experience as a living, breathing human, the more you have to pour into your photography. Live fuller and you’ll shoot better. That’s why learning about technical things is no guarantee that you’ll ever do anything with a camera beyond a certain clinical “okay-ness”. On the other hand, we see dreamers who are a solid C+ on the tech stuff deliver A++ images because their soul is part of the workflow.

NORMALEYE GALLERY UPDATE: HOME, HOME ON THE “RANGE”

By MICHAEL PERKINS

HISTORY BUFFS WHO HAVE EXHAUSTIVELY RESEARCHED THE HELLISH ANIMOSITY OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, a conflict which sowed seeds of resentment that bear bitter fruit to this very day, may have some small grasp of the vitriolic divide between those who espouse High Dynamic Range (HDR) photography and those who believe its practitioners are in league with Beelzebub. Pro-HDR factions believe those who resist this magical art should be forced to declare themselves Amish on the spot, while the opposite camp believes that all cameras that shoot HDR should be pulverized and used as landfill in Hades. We’re talking irreconcilable differences here.

When HDR first came to my attention, I welcomed it, as many others did, as a way to get around a long-standing problem in exposure….how to modulate between blackout and whiteout in extremely contrasty situations in which a single exposure would either blow out the sky through the window or bury the corners of an interior in blackness. My first attempts with it were exciting, as I tried to shoot frames bracketed across a three or five shot range of exposures, then smooth out the drastic differences between light and dark in the final image. The idea of using HDR for a sci-fi look or a painterly effect never appealed to me. I was really trying to use it to make my pictures replicate more closely the adjustment between light and dark that the eye makes instantaneously.

Over the last five years, however, as I review images I’ve made with HDR software. First, I use the program less with each passing year, and second, I no longer use it to retrieve “lost” tones in dark or light areas of an image. The program I have used since day one, Photomatix, has two main choices, Detail Enhancement and Tonal Compression, and, at first, I worked almost exclusively with the former. For wood grain, stone texture, botanical detail and cloud contrast, it’s remarkably effective. However, it’s also easy to produce images which are too dark overall, and accentuate noise in the individual images. Overcook it even a little and it looks like a finger painting done with hot lava. It thus actually works against the original “looks more like reality” objective.

On the other hand, producing the blended image in the Tonal Compression mode retains most of the sharp detail you get in Detail Enhancement without the gooey consistency. It has fewer attenuating controls, but as I go along, I find I am using it more because it simply calls less attention to itself. In either mode, I have made a conscious effort to throttle the heck back and under-process as much as I can. I’m just getting sick of shots that announce “hey, here comes an HDR photo!” two blocks ahead of its arrival.

I’m also in the middle of a back-to-basics phase based on getting things right, in-camera, in a single frame, and learning to be more accepting of dark and light patches rather than artificially mixed goose-ups of rebalanced tones. Anyway, as of this posting, I’ve taken down the original selection of images that was in the HDR gallery tab at the top of this page and loaded in a new batch that, while certainly not a “final” word on anything, shows, I think, that I’m still wrestling with the problem of how best to use this technology. Give them a look if you can, and let me know your thoughts on the use of HDR in your own work. We all have to figure out our own way to be home, home on “the range”.

DESTINATION VS. JOURNEY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE A WANDERING EYE. Not due to muscular weakness or marital infidelity, but to a malady particular to long-time photographers. After decades of shoots big and little, I find that I am looking for pictures nearly everywhere, so much so that, what appears to many normal people to be formless space or unappealing detail might be shaping up in my mind as My Next Project. The non-obvious sings out ever louder to me as I age, and may find its way into my pictures more often than the Celebrated Scenic Wonder, the Historically Important Site or the Big Lights In The Sky that attract 99% of the photo traffic in any given locality. Part of this has to do with having been disappointed in the past by the Giant Whatsis or whatever the key area attraction is, while being delightfully surprised by little things that, for me, deserve to be seen, re-seen, or testified to.

This makes me a lousy traveling companion at times, since I may be fixated on something merely “on the way” to what everyone else wants to see. Let’s say we’re headed to the Great Falls. Now who wants to photograph the small gravel path that leads to the road that leads to the Great Falls? Well, me. As a consequence, the sentences I hear most often, in these cases, are variations on “are you coming?“, “what are you looking at?” or, “Oh my God, are you stopping again????”.

Thing is, some of my favorite shots are on staircases, in hallways, around a blind corner, or the Part Of The Building Where No One Ever Goes. Photography is sometimes about destination but more often about journey. That’s what accounts for the staircase above image. It’s a little-traveled part of a museum that I had never been in, but was my escape the from gift shop that held my wife mesmerized. I began to wonder and wander, and before long I was in the land of Sir, We Don’t Allow The Public Back Here. Oddly, it’s easier to plead ignorance of anything at my age, plus no one wants to pick on an old man, so I mutter a few distracted “Oh, ‘scuse me”s and, occasionally, walk away with something I care about. Bonus: I never have any problem shooting as much as I want of such subjects, because, you know, they’re not “important”, so it’s not like queueing up to be the 7,000th person of the day doing their take on the Eiffel Tower.

Now, this is not a foolproof process. Believe me, I can take these lesser subjects and make them twice as boring as a tourist snap of a major attraction, but sometimes….

And when you hit that “sometimes”, dear friends, that’s what makes us raise a glass in the lobby bar later in the day.

ANATOMY OF A BOTCH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE SHOULD BE A MIRROR-IMAGE, “NEGATIVE” COOKBOOK FOR EVERY REGULAR ONE PUBLISHED, since there are recipes for inedible failures, just as surely as there are ones for gustatory delights. It might be genuinely instructive to read an article called How To Turn A Would-Be Apple Pie Into A Shapeless Heap Of Glop or You, Too Can Make Barbecue Ribs Look Like The Aftermath Of A Cremation. So too, in photography, I believe I could easily pen an essay called How To Take Pictures That Make It Seem That You Never Touched A Camera Before.

In fact…..

In recent days, I’ve been giving myself an extra welt or two with the flagellation belt in horrified reaction to a shoot that I just flat-out blew.It was a walk through a classic hotel lobby, a real “someday” destination for myself that I finally got to visit and wanted eagerly to photograph. Thing is, none of that desire made it into the frames. Nor did any sense of drama, art, composition, or the basics of even seeing. It’s rare that you crank off as many shots as I did on a subject and wind up with a big steaming pile of nothing to show for it, but in this case, I seem to have been all thumbs, including ten extra ones where my toes should be.

So, if I were to write a negative recipe for a shoot, it would certainly contain a few vital tips:

First, make sure you know nothing about the subject you’re shooting. I mean, why would you waste your valuable time learning about the layout or history of a place when you can just aimlessly wander around and whale away? Maybe you’ll get lucky. Yeah, that’s what makes great photographs, luck.

Enjoy the delightful surprise of discovering that there is less light inside your location than inside the fourth basement of a coal mine. Feel free to lean upon your camera to supply what you don’t have, i.e., a tripod or a brain. Crank up the ISO and make sure that you get something on the sensor, even if it’s goo and grit. And shoot near any windows you have, since blowouts look so artsy contrasted with pitch blackness.

Resist the urge to have any plan or blueprint for your shooting. Hey, you’re an artist. The brilliance will just flow as you sweep your camera around. Be spontaneous. Or clueless. Or maybe you can’t tell the difference.

Stir vigorously and for an insane length of time with a photo processing program, trying to manipulate your way to a useful image. You won’t get there, but life is a journey, right? Even when you’re hopelessly lost in a deep dark forest.

************************

You could say that I’m being too Catholic about this, and I would counter that I’m not being Catholic enough.

Until I do penance.

Gotta go back someday and do it right.

And make something that really cooks.

WHAT IS HIP?

Shooting “from the hip” can be an urban photographer’s secret weapon. 1/40 sec., f/3.5, ISO 500, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN FACED WITH A COMPLETELY DIFFERENT APPROACH TO OUR PHOTOGRAPHY, the crabbier among us are liable to utter one of two responses. Both sound negative, but one could be positive:

Response #1: “I’d never do that!” (Emphatically negative. Discussion over. You will not persuade me.)

Response #2:”Why would I want to do that???” (Possibly as close-minded as response #1, but the person could be asking a legitimate question, as in, ‘show me the benefit in doing it your way, because I can’t imagine a single reason why I should change’.)

When first reading about the street photography technique of “shooting from the hip”, I was a definite response #2. Wasn’t going to slam the door on trying it, but failed to see what I would get out of it. The phrase means just what you’d think it does, referring to people with obvious cameras who do “street” work, shooting with the camera hanging at waist level, never bringing the viewfinder up to their eye. Subjects don’t cringe or lock up because you don’t “seem” to be taking a picture, and thus your images of them are far more unguarded and natural.

Now, suggesting this to a person who has never even owned a camera that didn’t have a viewfinder is a little like asking him to try to take pictures from the inside of a burlap sack. Kinda makes my inner control freak throw a bratrum (a brat tantrum). Think of it from my point of view. If I shoot manually all the time (I do) and if I need my viewfinder like Linus needs his blanket (cause, hey, I’m a tortured and insecure artist), then squeezing off a shot without even knowing if it’s in frame is, to say the least, counter-intuitive (French for “nuts”).

So there you have your honestly expressed Response #2.

Some things that finally made it worth at least trying:

It don’t cost nothin’.

I can practice taking pictures that I don’t care about. I wouldn’t be shooting these things or people even with total control, so what’s to lose?

Did I mention it don’t cost nothin’?

Shooters beware: clicking from the hip is far from easy to master. Get ready to take lots of photos that look like they came from your Urban Outfitter Soviet Union-era Plastic Toy Hipsta Camera. You want rakish tilt? You got it. You like edgy, iffy focus? It’s a given. In other words, you’ll spend a lotta time going through your day’s work like the Joker evaluating Vicki Vale’s portfolio (….”crap….crap….crap….” ). But you might eventually snag a jewel, and it feels so deliciously evil to procure truly candid shots that you may develop an addiction to the affliction. Observe a few basics: shoot as wide as you can, cause 35s, 50s and other primes won’t give you enough scope in composition at close range: go with as fast a shutter speed as the light will allow (in low light, compromise on the ISO): if possible, shoot f/5.6 or smaller: and, finally,learn how to pre-squeeze the autofocus and listen for its quiet little zzzz, then tilt the camera just far enough up to make sure everyone has a head, and go.

At worst, it forces you to re-evaluate the way you “see” a shot, since you have no choice but to accept what the camera could see. At best, you might see fewer bared fangs from people snarling, “hey is that a $&@*! camera?” inches from your nose. And that’s a good thing.

SET AND SHOOT

Shooting manually means learning to trust that you can capture what you see. 1/160 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AUTOMODES ON CAMERAS ARE SUPPOSED TO AFFORD THE PHOTOGRAPHER AN ENHANCED SENSE OF COMFORT AND SAFETY, since, you know, you’re protected from your very human errors by the camera’s loving, if soulless, oversight. Guess wrong on a shutter speed? The auto has your back. Blow the aperture? Auto is on the case. And you always get acceptable pictures.

That is, if you can put your brain on automode as well.

Okay, that statement makes the top ten list for most arrogant openings in all of Blogdom, 2014. But I stand by it. I don’t think you should get comfortable with your equipment calling the shots. However, getting comfortable with your equipment’s limits and strengths, and gradually relying on your own experience for consistent results through exploitation of that knowledge….now that’s another thing entirely. It’s the difference between driving cross-country on cruise control and knowing, from years of driving, where in the journey your car can shine, if you drive it intelligently.

Photographers call some hunks of glass their “go-to” lenses, since they know they can always get something solid from them in nearly any situation. And while we all tend to wander around aimlessly for years inside Camera Toyland, picking up this lens, that filter, those extenders, we all, if we shoot enough for a long time, settle back into a basic gear setup that is reliable in fair weather or foul.

This is better than using automodes, because we have chosen the setups and systems that most frequently give us good product, and we have picked up enough wisdom and speed from making thousands of pictures with our favorite gear that we can “set and shoot”, that is, calculate and decide just as quickly as most people do with automodes…..and yet we keep the vital link of human input in the creative chain.

Like most, I have my own “go-to” lens and my own “safe bet” settings. But, just as you save time by not trying to invent the wheel every time you step up, you likewise shouldn’t be averse to greasing an old wheel to make it spin more smoothly.

How about that, I also made the top ten list for unwieldy metaphors.

A good day.

THE JOURNEY OF BECOMING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONCE MAN LEARNED TO SLICE A PATH THROUGH THE DARK WITH ANY KIND OF LIGHT, a romance with mystery began that photographers carry ever forward. Darkness and light can never be absolute, but duel with each other in a million interim stages at night, one never quite yielding to each other. A flickering lamp, a blazing torch, ten thousand LEDs, a lonely match, all shape the darkness and add the power of interpretation to the shaded side of the day. Photographers can only rejoice at the possibilities.

Spending a recent week in a vacation hotel, I fell into my typical habit of taking shots out the window under every kind of light, since, you know, you only think you understand what a view has to offer until you twist and turn it through variation. You’ve never beheld this scene before, so it’s just too easy to take an impression of it at random, leaving behind all other possibilities. The scene from this particular room, a mix of industrial and residential streets in central Pittsfield, Massachusetts, permits the viewer to see the town in the context of the Berkshire mountains, in which it nestles. Daylight, particularly early morning, renders the town as a charming, warm slice of Americana, not inappropriate in a village that is just a few miles away from the studio of painter Norman Rockwell. However, for me, the area whispered something else entirely after nightfall.

I can only judge the above frame by the combination of light and dark that I saw as I snapped it. Is it significant that the house is largely aglow while the municipal building in front of it is submerged in shadow? Is there anything in the way of mood or story that is conveyed by the lit stairs in the foreground, or the headlamps of the moving or parked cars? If the passing driver is subtracted from the frame, does the feel of the image change completely? Does the subtle outline of the mountains at the horizon lend a particular context?

That’s the point: the picture, any picture of these particular elements can only raise, not answer, questions. Only the viewer can supply the back end of the mystery raised by how it was framed or shot. Some things in the frame are on a journey of becoming, but art is not about supplying solutions, just keeping the conversation going. We’re all on our way somewhere. The camera can only ask, “what happens when we turn down this road?.”

That’s enough.

TAKING FLIGHT ONCE MORE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE CHARGES GIVEN TO ALL PHOTOGRAPHERS IS TO MARK THE PASSAGE OF TIME, to chronicle and record, to give testimony to a rapidly vanishing world. Certainly interpretation, fantasy, and other original conceptions are equally important for shooters, but there has been a kind of unspoken responsibility to use the camera to bear witness. This is especially difficult in a world bent on obliterating memory, of dismantling the very sites of history.

Humorist and historian Bill Bryson’s wonderful book, One Summer: America 1927 frames the amazing news stories of its title year around its most singular event, the solo transatlantic flight of Charles A. Lindbergh. A sad coda to the story reveals that nothing whatever remains of Roosevelt Field, the grassy stretch on Long Island from which the Lone Eagle launched himself into immortality, with the exception of a small plaque mounted on the back of an escalator in the mall that bears the field’s name. Last week, hauled along on a shopping trip to the mall with relatives, I made my sad pilgrimage to said plaque, lamenting, as Bryson did, that there is nothing more to photograph of the place where the world changed forever.

Then I got a little gift.

The mall is under extensive renovation as I write this, and much of the first floor ceiling has been stripped back to support beams, electrical systems and structural gridwork. Framed against the bright bargains in the mall shops below, it’s rather ugly, but, seen as a whimsical link to the Air Age, it gave me an idea. All wings of the Roosevelt Field mall feature enormous skylights, and several of them occur smack in the middle of some of the construction areas. Composing a frame with just these two elements, a dark, industrial space and a light, airy radiance, I could almost suggest the inside of a futuristic aerodrome or hangar, a place of bustling energy sweeping up to an exhilarating launch hatch. To get enough detail in this extremely contrasty pairing, and yet not add noise to the darker passages, I stayed at ISO 100, but slowed to 1/30 sec. and a shutter setting of f/3.5. I still had a near-blowout of the skylight, saving just the grid structure, but I was really losing no useful detail I needed beyond blue sky. Easy choice.

Thus, Roosevelt Field, for me, had taken wing again, if only for a moment, in a visual mash-up of Lindbergh, Flash Gordon, Han Solo, and maybe even The Rocketeer. In aviation, the dream’s always been the thing anyway.

And maybe that’s what photography is really for…trapping dreams in a box.

LIGHT DECAY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WE HAVE PROVEN OURSELVES TO BE A SPECIES THAT HATES TO BE SENT TO BED. Night life being a kind of “second shift” in most of the modern world, we really never lock up our cities for the evening, and that has changed how those cities exist for photographers.

Here’s both the good and bad news: there is plenty of light available after dark in most towns. Good if you want the special mix of neon, tube glow and LED burn that sculpts the contours of most towns post-sundown. Bad if you really want to see cities as special entities defined by shadow, as places where dark is a subtle but aesthetically interesting design element. In many mega-cities, we have really banished the dark, going beyond essential illumination to a bleachingly bright blast of light which renders everything, big and small, in the same insane mutation of color and tone. Again, this is both good and bad, depending on what kind of image you want.

Midtown Manhattan, downtown Atlanta, and anyplace Tokyo are examples of cities that are now a universe away from the partial night available in them just a generation ago. A sense of architectural space beyond the brightest areas of light can only be sensed if you shoot deep and high, framing beyond the most trafficked structures. Sometimes there is a sense of “light decay”, of subtler illumination just a block away or a few stories higher than what’s seen at the busiest intersections. Making images where you can watch the light actually fade and recede adds a little dimension to what would otherwise be a fairly flat feel that overlit streets can generate.

Photography is often a matter of harnessing or collecting extra light when it’s scarce. Turns out that having too much of it is a creative problem in the opposite direction.

SETTING THE CAPTIVES FREE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’D LIKE TO ERADICATE THE WORD “CAPTURE” FROM MOST PHOTOGRAPHIC CONVERSATIONS. It suggests something stiff or inflexible to me, as if there is only one optimum way to apprehend a moment in an image. Especially in the case of portraits, I don’t think that there can be a single way to render a face, one perfect result that says everything about a person in a scant second of recording. If I didn’t capture something, does that mean my subject “got away” in some way, eluded me, remains hidden? Far from it. I can take thirty exposures of the same face and show you thirty different people. The word has become overused to the point of meaningless.

We are all conditioned to think along certain bias lines to consider a photograph well done or poorly done, and those lines are fairly narrow. We defer to sharpness over softness. We prefer brightly lit to mysteriously dark. We favor naturalistically colored and framed recordings of subjects to interpretations that keep color and composition “codes” fluid, or even reject them outright. It takes a lot of shooting to break out of these strictures, but we need to make this escape if we are to move toward anything approaching a style of our own.

I remember being startled in 1966 when I first saw Jerry Schatzberg’s photograph of Bob Dylan on the cover of the Blonde On Blonde album. How did the editor let this shot through? It’s blurred. It’s a mistake. It doesn’t…..wait, I can’t get that face out of my head. It’s Bob Dylan right now, so right now that he couldn’t be bothered to stand still long enough for a snap. The photo really does (last time I say this) capture something fleeting about the electrical, instantaneous flow of events that Dylan is swept up in. It moves. It breathes. And it’s more significant in view of the fact that there were plenty of pin-sharp frames to choose from in that very same shoot. That means Schatzberg and Dylan picked the softer one on purpose.

There are times when one 10th of a second too slow, one stop too small, is just right for making the magic happen. This is where I would usually mention breaking a few eggs to make an omelette, but for those of you on low-cholesterol diets, let’s just say that n0 rule works all the time, and that there’s more than one way to skin (or capture) a cat.

FREE ATMOSPHERE

Panos are not for every kind of visual story. The best thing is, you can make them so quickly, it’s easy to see if it’s merely a gimmick effect or the perfect solution, given what you need to say.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PANORAMIC APPS FOR MOBILE CAMERAS CONSTITUTE A HUGE STEP FORWARD in convenience and simplicity in taking the kind of sweeping images that used to require keen skills either in film processing or in digital darkroom stitching. The newest versions of these apps are far from flawless, and, like any effect-laden add-on, they can become cheesy gimmicks, or, used to excess, merely boring. That said, there is a time and place for everything.

99% of the impact in a pano comes from the selection of your subject. Supposing a panoramic view to be a specialized way to tell a story, is the story you’re attempting to tell interesting in its own right? Does it benefit from the wider frame? Let’s recall that, as well as including a ton of extra left-and-right information, handheld pano apps create a distorted version of reality. In the earliest days of panoramas, multiple photos of a scene were taken side-by-side, all with the same distance from camera to subject. This was usually accomplished by shooting on a tripod, which was moved and measured with each new portion of what would eventually be a wide composite. At each exposure, the distance of the tripod to, say, the mountain range was essentially constant across the various exposures, rendering the wide picture all in the same plane….an optically accurate representation of the scene.

With handheld panos done in-camera, the shooter and his camera must usually pivot in a large half-circle, just as you might execute a video pan,so that some objects are closer to the lens than others, usually near the center. This guarantees a huge amount of dramatic distortion in at least one part of the image, and frequently more than one. The effect is that you are not just recording a straight left-to-right scene, but creating artificial stretches and warps of everything in your shot. You are not recording a scene that unfolds across a straight left-right horizon, but capturing things that actually encircle you and trying to “flatten them out” so they appear to occur in one unbroken line. By showing objects that may be beside or behind you, you’re kinda making a distortion of an illusion. Huh?

Again, if this is the look you want, that is, if your subject is truly served by this fantasy effect, than click away. You’ll know in a minute if it all made sense, anyhow, and that alone is a remarkable luxury. These days, we can not only get to “yes” faster, we can, more importantly, get rid of all the “no’s” in an instant as well.

THE ENNOBLING GOLD

Brooklyn Block, 2014. No, this building isn’t this pretty in “reality”. And that’s the entire point. 1/100 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LIGHT IS THE ULTIMATE MAKE-UP ARTIST, the cosmetic balm that paints warmth, softness, even a kind of forgiveness, or dignity onto the world. Photographers use light in a different way than painters, since a canvas, beginning as a complete blank, allows the dauber to create any kind of light scheme he desires. It’s a very God-like, “let there be light” position the painter finds himself in, whereas the photographer is more or less at light’s mercy, if you will. He has to channel, harness, or manage whatever the situation has provided him with, to wrangle light into an acceptable balance.

No complaints about this, by the way. There’s nothing passive about this process: real decisions are being made, and both painters and photographers are judged by how they temper and combine all the elements they use in their assembly processes. Just because a shooter works with light as he finds it, rather than brushing it into being, doesn’t make him/her any less in charge of the result. It’s just a different way to get there.

Light always has the power to transform objects into, if you will, better versions of themselves. I call it the “ennobling gold”, since I find that the yellow range of light is kindest to a wider range of subjects. Stone or brick, urban crush or rural hush, light produces a calming, charming effect on nearly anything, which is what makes managing light so irresistible to the photographer. He just knows that there is beauty to be extracted when the light is kind. And he can’t wait to grab all he can.

“Light makes photography”, George Eastman famously wrote. “Light makes photography. Embrace light. Admire it. Love it. But, above all, know light. Know it for all you are worth, and you will know the key to photography.”

Yeah, what he said.

AVOIDING THE BURN

AS A PHOTOGRAPHER, YOU CAN EMPATHIZE WITH THAT FAMOUS MOTH AND HIS FATAL FASCINATION with a candle flame….especially if you’ve ever flirted too close to the edge of a blowout with window light. You want to gobble up as much of that golden illumination as possible without singeing your image with a complete white-hot loss of detail. Too much of a good thing and all that.

However, a window glowing with light is one of the most irresistible of candies for a shooter, and you can fill up a notebook with attempted end-arounds and tricks to harvest it without getting burned. Here’s one cheap and easy way:

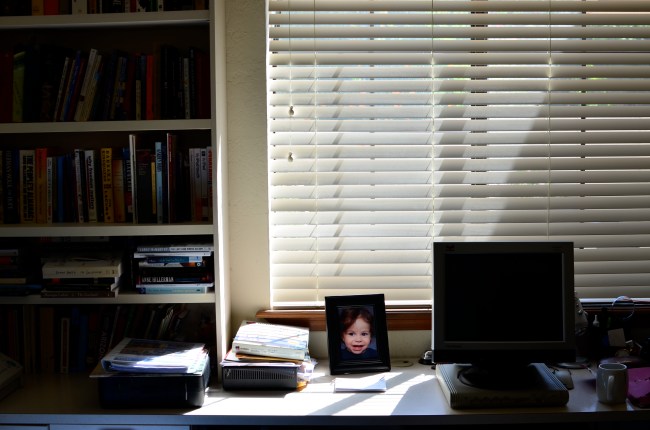

In this first attempt to capture the early morning shadows and scattered rays in my office at 1/100 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, you’ll see that the window is a little too hot, and that nearly everything ahead of the window is rendered into a silhouette. And that’s a shame, since the picture, to me, should be not only about the window light, but also its role in partially lighting a dark room. I don’t want to make an HDR here, since that will completely over-detail the stuff in the dark and look un-natural. All I really need is a hint of room light, as if a small extra bit of detail has been illuminated by the window, but just that….a small bit.

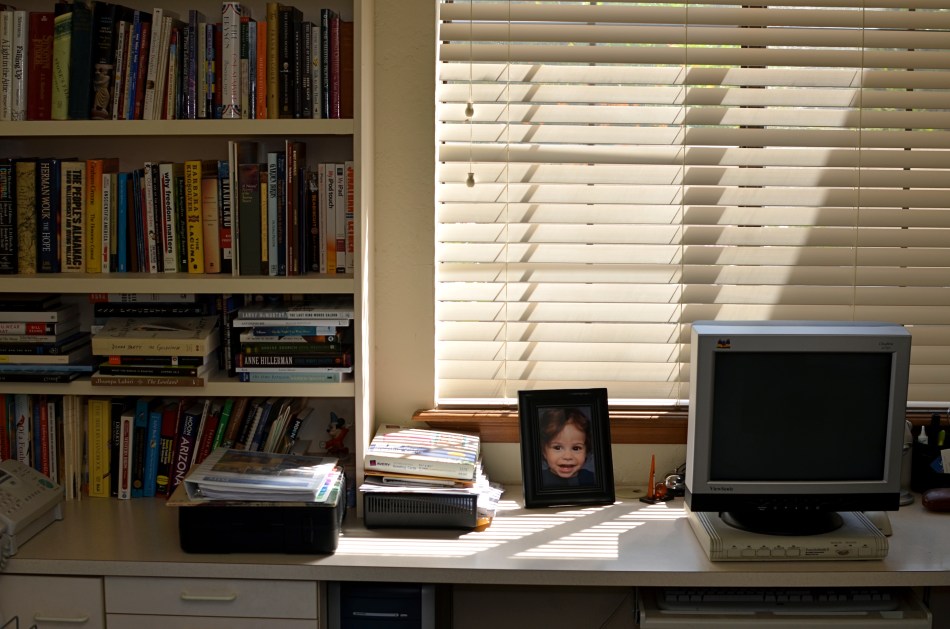

In the second attempt, I have actually halved the shutter speed to 1/200 to underexpose the window, but have also used my on-camera flash with a bounce card to ricochet a little light off the ceiling. I am almost too far away for the flash to be of any real strength, but that’s exactly what I’m looking for: I want just a trace of it to trail down the bookshelf, giving me some really mild color and allowing a few book titles to be readable. The bounce plus the distance has weakened the flash to the point that it plausibly looks as if the illumination is a result of the window light. And since I’ve underexposed the window, even the wee bit of flash hasn’t blown out the slat detail from the blinds.

Overall, this is a cheap and easy fix, happens in-camera, and doesn’t call attention to itself as a technique. There are two kinds of light: the light that is natural and the light that can be made to appear natural. If you can make the two work smoothly together, you can fly close to the flame while avoiding the burn.

THE (LATENT) BLUES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WE HAVE CONTROL OVER NEARLY EVERY PART OF THE PHOTOGRAPHIC PROCESS BUT… ACCESS. We can learn to master aperture, exposure, composition, and many other basics of picture making, but we can’t help the fact that we are typically at our shooting location for one time of day only.

Whatever “right now” may be….morning, afternoon, evening….it usually includes one distinct period in the day: the pier at sunset, the garden at break of dawn. Unless we have arranged to spend an extended stretch of time on a shoot, say, chasing the sun and shadows across a daylong period from one location at the Grand Canyon or some such, we don’t tend to spend all day in one place. That means we get but one aspect of a place…however it’s lit, whoever is standing about, whatever temporal events are native to that time of day.

Many locations that are easily shot by day are either unavailable or technically more complex after sundown. That’s why the so-called “day for night” effect appeals to me. As I had written sometime back, the name comes from the practice Hollywood has used for over a hundred years to save time and ensure even exposure by shooting in daylight and either processing or compensating in the camera to make the scene approximate early night.

In the case of the image you see up top, I have created an illusion of night through the re-contrasting and color re-assignment of a shot that I originally made as a simple daylight exposure. In such cases, the mood of the image is completely changed, since the light cues which tell us whether something is bright or mysterious are deliberately subverted. Light is the single largest determinant of mood, and, when you twist it around, it reconfigures the way you read an image. I call these faux-night remakes “latent blues”, as they generally look the way the sky photographs just after sunset.

This effect is certainly not designed to help me avoid doing true night-time exposures, but it can amplify the effect of images that were essentially solid but in need of a little atmospheric boost. Just because you can’t hang around ’til midnight, you shouldn’t have to do without a little midnight mood.

TURN THE PAGE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’M VERY ACCUSTOMED TO BEING STOPPED IN MY TRACKS AT A PHOTOGRAPH THAT EVOKES A BYGONE ERA: we’ve all rifled through archives and been astounded by a vintage image that, all by itself, recovers a lost time.

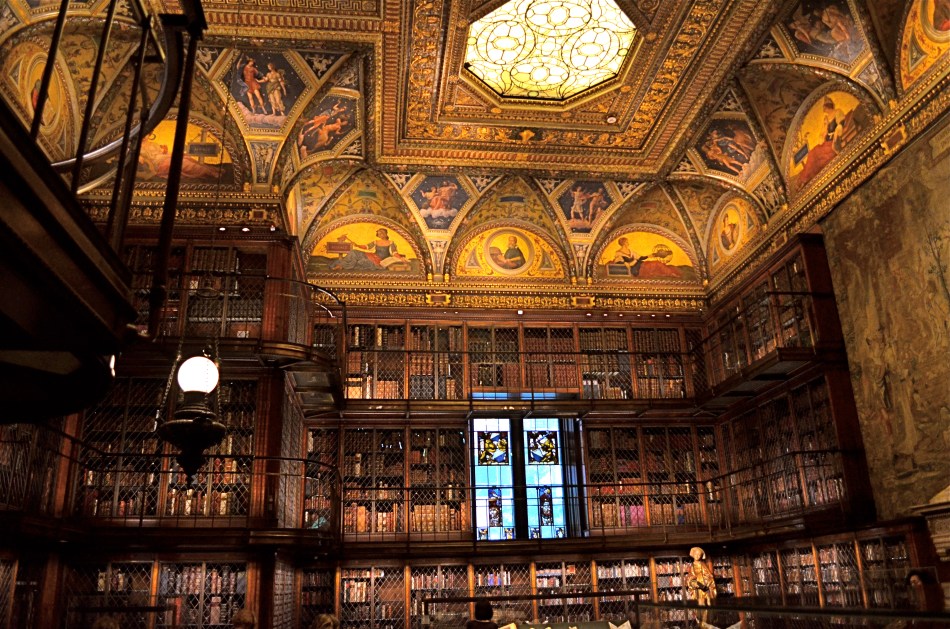

It’s a little more unsettling when you experience that sense of time travel in a photo that you just snapped. That’s what I felt several weeks ago inside the main book trove at the Morgan Library in New York. The library itself is a tumble through the time barrier, recalling a period when robber barons spent millions praising themselves for having made millions. A time of extravagant, even vulgar displays of success, the visual chest-thumping of the Self-Made Man.

The private castles of Morgan, Carnegie, Hearst and other larger-than-life industrialists and bankers now stand as frozen evidence of their energy, ingenuity, and avarice. Most of them have passed into public hands. Many are intact mementos of their creators, available for view by anyone, anywhere. So being able to photograph them is not, in itself, remarkable.

A little light reading for your friendly neighborhood billionaire. Inside the Morgan Library in NYC.

No, it’s my appreciation of the fact that, today,unlike any previous era in photography, it’s possible to take an incredibly detailed, low-light subject like this and accurately render it in a hand-held, non-flash image. This, to a person whose life has spanned several generations of failed attempts at these kinds of subjects, many of them due to technical limits of either cameras, film, or me, is simply amazing. A shot that previously would have required a tripod, long exposures, and a ton of technical tinkering in the darkroom is just there, now, ready for nearly anyone to step up and capture it. Believe me, I don’t dispense a lot of “wows” at my age, over anything. But this kind of freedom, this kind of access, qualifies for one.

This was taken with my basic 18-55mm kit lens, as wide as possible to at least allow me to shoot at f/3.5. I can actually hand-hold fairly steady at even 1/15 sec., but decided to play it safe at 1/40 and boost the ISO to 1000. The skylight and vertical stained-glass panels near the rear are WINOS (“windows in name only”), but that actually might have helped me avoid a blowout and a tougher overall exposure. So, really, thanks for nothing.

On of my favorite Twilight Zone episodes, the one about Burgess Meredith inheriting all the books in the world after a nuclear war, with sufficient leisure to read his life away, was entitled “Time Enough At Last”. For the amazing blessings of the digital age in photography, I would amend that title by one word:

Light Enough…At Last.

GET THEE TO A LABORATORY

by MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHIC SUBJECT MATTER, ONCE YOU’VE TRAINED YOURSELF TO SPOT IT, is always in ready supply. But, let’s face it: many of these opportunities are one-and-done. No repeats, no returns, no going back for another crack at it. That’s why, once you learn to make pictures out of almost nothing, it’s like being invited to a Carnival Cruise midnight buffet to find something that is truly exploding with possibilities, sites that actually increase in artistic value with repeat visits. I call such places “labs” because they seem to inspire an endless number of new experiments, fresh ways to look at and re-interpret their basic visual data.

My “labs” have usually been outdoor locations, such as Phoenix’ Desert Botanical Gardens or the all-too-obvious Central Park, places where I shoot and re-shoot over the space of many years to test lenses, exposure schemes, techniques, or, in the dim past, different film emulsions. Some places are a mix of interior and exterior and serve purely as arrangements of space, such as the Brooklyn Museum or the Library of Congress, where, regardless of exhibits or displays, the contours and dynamics of light and form are a workshop all in themselves. In fact, some museums are more beautiful than the works they house, as in the case of Guggenheim in NYC and its gorgeous west coast equivalent, The Getty museum in Los Angeles.

No color? No problem. Interior view of the Getty’s visitor center. 1/640 sec., f/5.6. ISO 100, 35mm.

Between the gleaming white, glass-wrapped buildings of this enormous arts campus and its sinuous, sprawling gardens (not to mention its astounding hilltop view), the Getty takes one complete visit just to get yourself visually oriented. Photographically, you will find a million isolated tableaux within its multi-acre layout upon subsequent trips, so there is no end to the opportunities for exploring light, scale, abstraction, and four full seasons of vibrant color. Not a color fan? Fine. The Getty even dazzles in monochrome or muted hues. It’s like Toys ‘R’ Us for photogs.

I truly recommend laying claim to a laboratory of your own, a place that you can never truly be “finished with”. If the place is rich enough in its basic components, your umpteenth trip will be as magical as your first, and you can use that one location as a growth graph for your work. Painters have their muses. Shooter Harry Calahan made a photographic career out of glorifying every aspect of his wife. We all declare our undying love for something.

And it will show in the work.

FRONT TO BACK

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NOT ALL PORTRAITS INVOLVE FACES.

I’ll let that little bit of blasphemy sink in for a moment. After all, the face is supposed to be the key to a persona’s entire identity, and God knows that many a mediocre shot has been saved by a fascinating expression, right? The eyes are the window to the soul, and so on, and so forth, etc., etc.

But is this “face-centric” bias worthy of photographers, who are always re-writing the terms of visual engagement on every conceivable subject? Is there one single way to make a person register in an image? Obviously I don’t believe that, or else I wouldn’t have started this argument, but, beyond my native contrariness, I just am not content with there being a single, approved way of visualizing anything. I’ve seen too much amazing work done from every conceivable standpoint to admit of any limitation, or need for a “rule”, even when it comes to portraiture.

The face is many things, but it’s not the entire body, and even if you capture a shot in which the subject’s face is absent, he or she can be so very present in the feel of the picture. Arms, shoulders, the sinews, the stance, the way a body stands in a frame…all can bear testimony.

I recently stumbled onto an impromptu performance by a young string quartet, and faced the usual problem of not being able to simultaneously do justice to all four members’ faces, to balance the tension and concentration written on all their features in performance. In such situations, you have to make some kind of call: the picture becomes a dynamic tension between the shown and the hidden, just as the music is a push-and-pull between dominant and passive forces. You must decide what will remain unseen, and, sometimes, that’s a face.

As the music evolved, the two ladies seen above were, in different instants, either in charge of, or at the service of, the energy of the moment. For this picture, I saw more strength, more power in the back of the violinist than in the front of the cellist. It was body language, a kind of structural tug between the pair, and I voted for what I could not show fully. As it turned out, the violinist actually has a lovely face, one possessing a stern, disciplined intensity. On another day, her story would have been told very differently.

On this day, however, I was happy to have her turn her back on me.

And turn my own head around a bit.