A FORWARD STEP BACK

Skies which appear wispy in color can pick up some drama in black & white with the use of a red filter.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SOME CHOICES IN LIFE ARE BINARY, EITHER YES OR NO. The light switch is either all “on” or all “off”. Photographic choices have never been binary, since there are only a few real rules about how to achieve the image you want and more than a million reasons why those rules have to be jettisoned, because they actually stand in the way of that image.

When digital photography arrived, there was a tendency to assert that everything associated with film photography was as obsolete as a roll of Kodachrome 64. In fact, the further we proceed into the digital age, the more we realize that there are many good practices from the days of emulsions and negatives that have solid application in the age of zeroes and ones. It would be ridiculous to say categorically that every tool of one era must be abandoned in the image-making of the next. Lenses, exposure, lighting basics, and many more elements of film-based creativity have equivalents in digital. None of them are good all the time, and none of them should be ruled out without exception.

The use of filters is one such element. Many film-based photogs worth their salt have used filters as a matter of course, and, despite the amazing in-camera and post-production fixes of the present day, these little bits of accent glass still produce dazzling effects with a minimum of investment, and help shooters maintain a close, hands-on control of their images in the moment. And one of my favorites here in the American southwest, land of endless, often blistering sun, is the red 25 filter.

Used to punch up contrast and accentuate detail for black and white, the red 25 renders even the lightest skies into near blackness, throwing foreground objects into bold relief and making shadows iron sharp. On a day when fluffy clouds seem to blend too much into the sky, the red 25 makes them pop, adding additional textural detail and a near-dimensional feel to your compositions. Additionally, the filter dramatically cuts haze, adding clear, even tones to the darkened skies. Caution here: the red 25 could cost you several stops of light, so adjust your technique accordingly.

Many whose style has developed in the digital age might prefer to shoot in color, then desaturate their shots later, simulating this look purely through software, but I prefer to make my own adjustments to the scene I’m shooting while I am shooting it. I wouldn’t paint a canvas in one place and then fix my choice of colors a week later, hundreds of miles away from my dream sunset. Filters are from a world where you conceive and shoot now. The immediate feedback of digital gives you the part of that equation that was absent in film days, that is, the ability to also fix it, now. Photography can’t afford to cut itself off from its own history by declaring tools from any part of that history obsolete. A forward step, back is often the deftest dance move.

THE VANISHED NORMAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE FUTURE DOESN’T ARRIVE ALL AT ONCE, just as the past doesn’t immediately vanish completely. In terms of technology, that means that eras kinds of smear across each other in a gradual “dissolve”. Consider the dial telephone, which persisted in various outposts for many years after the introduction of touch-tone pads, or, more specifically, Superman’s closet, the phone booth, which stubbornly overstayed its welcome long past the arrival of the cel. The “present” is always a mishmosh of things that have just arrived and things that are going away. They sort of pass each other, like workers at change of shift.

Photographically, this means that there are always relics of earlier eras that persist past their sell-by date. They provide context to life as part of a kind of ever-flowing visual history. It also means that you need to seize on these relics lest they, and their symbolic power, are lost to you forever. Everything that enjoys a brief moment as an “everyday object” will eventually recede in use to such a degree that younger generations couldn’t even visually identify it or place it in its proper time order (a toaster from 1900 today resembles a Victorian space heater more than it does a kitchen appliance).

Ironically, this is a double win for photographers. You can either shoot an object to conjure up a bygone era, or you can approach it completely without context, as a pure design element. You can produce substantial work either way.

Some of the best still life photography either denies an object its original associations or isolates it so that it is just a compositional component. The thing is to visually re-purpose things whose original purpose is no longer. Photography isn’t really about what things look like. It’s more about what you can make them look like.

LOW-TECH LOW LIGHT

Passion Flower, 2015. Budget macro with magnifying diopters ahead of a 35mm lens. 1/50 sec., f/7.1, ISO 100.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LIGHT IS THE PRINCIPAL FUEL OF PHOTOGRAPHY, but it needs refinement, just as crude oil needs to be industrially altered before it’s ready for consumer use. It isn’t just enough to record light in its natural form; it has to be corralled, directed, harnessed so that it enhances a photograph in such a way that, ironically, makes it look like you did nothing at all but press the shutter. So, right at the start, making images is a bit of a con job. Good thing is, it’s only dishonorable when you get caught.

Doing macro on the cheap with the use of screw-on magnifying diopters ahead of your regular lens is one of the situations that can create special lighting challenges. There is an incredibly shallow depth of field in these lenses, but if you compensate for it in the camera, by, say, f/8 or higher, you lose light like crazy. Slow down your shutter to compensate, and you’re on a tripod, since the slightest tremor in a hand-held shot looks like 7.8 on the Richter scale. Keep the shorter shutter speed, though, and you’re jacking ISO up, inviting excessive noise. Flood the shot with constant light, and you might alter the color relationships in a naturally lit object, effecting, well, everything that might appeal in a macro shot.

Best thing is, since you’re shooting such a small object, you don’t need all that much of a fix. In the above shot, for example, the garlic bulb was on a counter about two feet from a window which is pretty softened to start with. That gave me the illumination I needed on the top and back of the bulb, but the side facing me was in nearly complete shadow. I just needed the smallest bit of slight light to retrieve some detail and make the light seem to “wrap” around the bulb.

Cheap fix; half a sheet of blank typing paper from my printer’s feed tray, which was right next door. Camera in right hand, paper in left hand, catching just enough window light to bounce back onto the front of the garlic. A few tries to get the light where I wanted it without any flares. The paper’s flat finish gave me even more softening of the already quiet window light, so the result looked reasonably natural.

Again, in photography, we’re shoving light around all the time, acting as if we just walked into perfect conditions by dumb luck. Yeah, it’s fakery, but, as I say, just don’t get caught.

THE DAY THE UNIVERSE CHANGED

Outgunned, 2015. 1/30 sec., f/2.8, ISO 400, 35mm. Copy of color original desaturated with Nikon’s “selective color” in-camera touch-up option.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT WAS NEARLY A GENERATION AGO that Professor James Burke was the most admired media “explainer” of history and culture on both sides of the Atlantic, largely as a result of video adaptations of his hit books Connections and The Day The Universe Changed. Burke, trained at Jesus College in Oxford, was spectacularly talented at showing the interlocking linkages of events and human development, demonstrating the way they meshed together to act endlessly upon history, like gears locked in one large rotation. The result for viewers on PBS and the BBC was better than an ah, ha moment. It was more like an of course moment. Oh, yes, I see now. Of course.

In Universe especially, he examined the specific moments when everything we “knew” was altered forever. For example, we all “knew” the earth was flat, until we knew the exact opposite. We all “knew” that the sun rotated around the Earth, right up until that belief was turned on its ear. Our ideas of truth have always been like Phoenix birds, flaming out of existence only to rise, reconfigured, out of their own ashes. Burke sifted the ashes and set our imaginations ablaze.

As photographers, we have amazing opportunities to depict these transformative moments. In the 1800’s, the nation’s industrial sprawl across the continent was frozen in time with photo essays on the dams, highways, railroads and settlements that were rendering one reality moot while promising another. In the early 1900’s we made images of the shift between eras as the horrors of World War One rendered the Victorian world, along with our innocence, obsolete.

I love exploring these instants of transformation by way of still-life compositions that represent change, the juncture of was and will be. Like the above arrangement, in which some kind of abstract artillery seems to have un-horsed the quaint army of a chess set, I am interested in staging worlds that are about to go out of fashion. Sometimes it takes the form of a loving portrait of bygone technology, such as a preciously irrelevant old camera. Other times you have to create a miniature of the universe you are about to warp out of shape. Either way, it makes for an amazing exercise in re-visualizing the familiar, and reminds us, as Professor Burke did so well, that truth is both more, and less, than we know.

HAPPY OLD YEAR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

The White Rabbit put on his spectacles. ‘Where shall I begin, please your Majesty?’ he asked. ‘Begin at the beginning,’ the King said gravely, ‘and go on till you come to the end: then stop.’

IN A SIMPLER WORLD, THE KING OF HEARTS, quoted above in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, would be perfectly correct. All things being equal, the beginning would be the best place to begin. But, in photography, as in all of life, we are always coming upon a series of beginnings. Learning an art is like making a lap in Monopoly. Just when we think we are approaching our destination, we pass “Go” again, and find that one man’s finish line is another man’s starting gate. Photography is all about re-defining where we are and where we need to be. We always begin, and we never finish.

As 2014 comes to an intersection (I can’t really say ‘a close’ after all that, can I?), it’s normal to review what might be either constant, or changed, about one’s approach to making pictures. That, after all, is the stated aim of this blog, making The Normal Eye more about journey than destination. And so, all I can do in reviewing the last twelve months of opportunities or accidents is to try to identify the areas of photography that most define me at this particular juncture, and to reflect on the work that best represents those areas. This is not to say I’ve gained mastery, but rather that I’m gaining on it. If my legs hold out, I may get there yet. But don’t count on it.

The number twelve has become, then, the structure for the blog page we launch today, called (how does he think of these things?) 12 for 14. You’ll notice it as the newest gallery tab at the top of the screen. There is nothing magical about the number by itself, but I think forcing myself to edit, then edit again, until the thousands of images taken this year are winnowed down to some kind of essence is a useful, if ego-bruising, exercise. I just wanted to have one picture for each facet of photography that I find essentially important, at least in my own work, so twelve it is.

Light painting, landscape, HDR, mobile, natural light, mixed focus, portraiture, abstract composition, all these and others show up as repeating motifs in what I love in others’ images, and what I seek in my own. They are products of both random opportunity and obsessive design, divine accident and carefully executed planning. Some are narrative, others are “absolute” in that they have no formalized storytelling function. In other words, they are a year in the life of just another person who hopes to harness light, perfect his vision, and occasionally snag something magical.

So here we are at the finish line, er, the starting gate, or….well, on to the next picture. Happy New Year.

WATERCOLOR DAYS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE FIRST COLOR PHOTOGRAPHS REALLY…WEREN’T. That is to say, the various recording media, from glass plates to film, were technically incapable of rendering color, leaving entrepreneurial craftsmen (mostly post card artists) to lovingly apply hues with paint and brush. It was the Fred Flintstone version of Photoshop, and, boy howdy, did it sell, regardless of the fact that most flesh tones looked like salmon and most skies looked more eggshell than azure. Until the evolution of a film-based process near the end of the 19th century, these watercolor pastels stood in for the real thing.

Winter’s months-long overcasts and grey days can remind a photographer of what it was like to only be able to capture some of the color in a given subject, as the change in light washes the brilliance out of the world, leaving it like a faded t-shirt and creating the impression that color, as well as botany, goes into the hibernational tomb during winter.

Of course, we can boost the hues in the aftermath just like those patient touch-up artists of the 1800’s, but in fact there are things to be learned from rendering tones on the soft pedal. In fact, reduced color is a kind of alternate reality. Capturing it as it actually appears, rather than amping it up to neon rudeness, can actually be a gentle shaper of mood.

Light that seeps through cloud cover is diffused, and shadows, if they survive at all, are faint and soft. The look is really reminiscent of early impressionism, and, when matched up with the correct subject matter, can complement a scene in a way that a more garish spectrum would only ruin.

Just like volume in music, color in photography is meant to speak at different decibel levels depending on the messaging at hand. Winter is a wonderful way to force ourselves to work out of a distinctly different paint box.

FIVE-DECKER SANDWICH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MY PHOTOGRAPHY IS OCCASIONALLY AKIN TO MY GRANDMOTHER’S COOKING METHOD, which produced culinary miracles without a trace of written recipes or cookbooks. Her approach was completely additive; she merely kept throwing things into the pot until it looked “about right”. I was aware of the difference, in her hands, between portions that were labeled “smidges”, “tastes”, “pinches” and even “tads” (as in, “this is a tad too bitter. Give me the salt.) I never questioned her results: I merely scarfed them down and eagerly asked for seconds.

Picture making can also be a matter of adding enough pinches and tads to create just the right mix of factors for the image you need. It’s frequently as instinctual a process as Gram’s, but sometimes you have to analyze what worked by thinking the shot backwards after the fact. In the case of the above image, what you see, although it was shot very quickly, is actually the convergence of several different ingredients, the combination of which would be all wrong for some photos, but which actually served this subject fairly well.

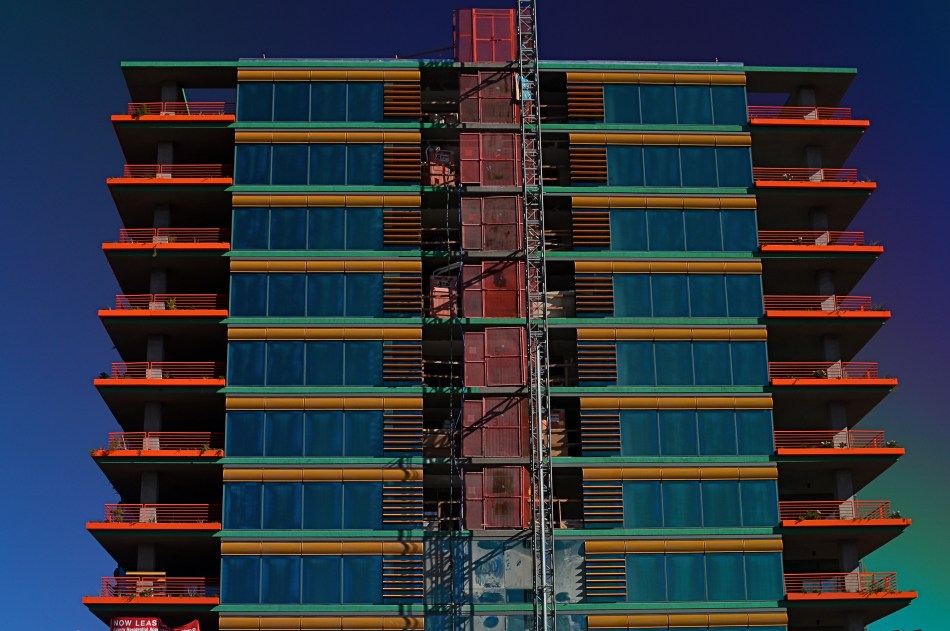

The five-decker sandwich of factors in the shot begins with the building, which is quite intense in color all by itself, yet not quite contrasty enough to suit me in this specific instance. So let’s see all the hoops the camera had to jump through to get this particular image:

First, it was taken during the so-called “golden hour”, just before sunset, in late fall in Arizona. That guarantees at least one boost of the building’s native intensity. The next factor is the camera’s own color settings, which are set to “vibrant.” Level three comes from a polarizing filter, which is juicing the sky from its hazy southwestern “normal” to a deep blue. For the fourth element, I am also adding a second filtering component by shooting through a heavily tinted car window (there’s no other kind in Arizona), which presents here as the gradation of sky from blue at the top of the frame to a near aqua near the bottom. And finally, I am way under-exposing the shot at 1/320, deepening the colors yet one more time.

The fun of this is that it all happens ahead of the click, and keeps your fingers off the Photoshop trigger. Grandma may not have spent any more time laboring over a photo than a quick snap of a box Brownie, but she knew how to take stew meat and morph it into filet. And, as with the making of a picture, you just keep adding stuff until the mixture in the pot looks “about right.”

PUBLIC INTIMACY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

OKAY, I JUST REALIZED HOW GROSSLY MISLEADING THE TITLE OF THIS POST COULD SEEM, but, trust me, I never meant it the way it sounds. I was just struggling to find a phrase for the kind of photograph in which a person is as private as possible while on full display to the world at large. There are behaviors that are intensely personal and astonishingly public at the same time, and such events in a human being’s life are rife, for the photographer, with a very singular kind of drama.

We like to think of ourselves as sufficiently camouflaged behind the carefully crafted mask that we present for the public’s consumption, all the better to preserve our sense of privacy. But there are always cracks in the mask, fleeting signals at the raw life underneath. Learning to detect those cracks is the talent of the street photographer, whose eye is always trained beyond the obvious.

Mourning, Joy, Discovery…all these things provide a teeter-totter balance between public display and private truth. The primal basics of life bring that juggling act into view, and, as a photographer, I am often surprised how much of them is in evidence in the simple act of nourishing ourselves. Dining would seem, on the surface, to be all about simple survival. Eating to live, and all that. But meals are laden with ritual and habit, the most hard-wired parts of one’s personality. Food gathers people for so much more than mere sustenance. It is memory, community, religion, friendship, negotiation, reassurance, replenishment. It is a symbol for life (and its passing), a trigger for shared experience, a talisman, a consecration.

Case in point: the man and woman in the above image were seen in a Los Angeles restaurant late on a Saturday night. Their relationship would seem to be that of mother and son, but it could be grandmother and nephew, son-in-law and mother-in-law, or a dozen other arrangements. A sharp contrast is provided by their comparative ages and physicality. One sits upright, while the other sits as well as she can. There is no eye contact….but does that necessarily mean that they do not want to see each other? There is no conversation. Has everything already been said? Are they grateful to still be there for each other after all these years, or is this the fulfillment of an obligation, a visitation occasioned by guilt?

Eating is a microcosmic examination of everything that it means to be human. So much for a single photographic frame to try to capture. So many ways of looking into the publicness of privacy.

PRIME OPPORTUNITY

It’s wide. It’s sharp.Its proportions are natural. What else do I need in this image, shot with a 35mm prime lens, that dictates shooting it with a wideangle zoom?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SOMEWHERE BETWEEN THE END OF THE FILM ERA AND THE DAWN OF THE DIGITAL AGE IN PHOTOGRAPHY, there was a profound change in what camera manufacturers defined as a “starter” lens for new owners. Many shooters, including your humble scribbler, have wondered just why an 18-55 “kit lens” zoom became the glass that was included with the purchase of a digital SLR, when the baseline lens for film shooters had most typically been a 35mm prime. This is especially puzzling since the kit lenses sold by many makers are optically inferior to a prime in several key respects.

Primes, or “normal” lenses, have one focal length only, and so cannot zoom at all, but they out-perform many of today’s zooms on sharpness, clarity, speed, aesthetic blur (or “bokeh”), and portability. Their proportions are more similar to those seen by the human eye (thus the “normal” tag) and so do not create distortion at, say 24mm, a range at which some banding creeps into a zoom at the same focal length. They also will not exaggerate front-to-back distances as seen in a super wide-angle, meaning that an 8×10 room does not resemble a bowling alley.

So what does a wide-angle zoom bring to the party? Not much, beyond the convenience afforded by zooming out with the twist of a barrel, filling your frame in seconds but, ironically, making you less mindful of the composition of your shot. The few extra seconds needed to compose on a lens that can’t zoom means that you act more purposefully, more consciously in the making of an image. You, and not the lens, are responsible for what’s included or cut.

But let’s assume that you want the kit lens for its wide-angle. This is also no problem for a prime lens. Yes, it’s as wide as it will ever be at a single focal length, but you can change what it sees by just stepping backwards. A 35mm prime is plenty wide depending on where you stand. It’s not like you can’t capture a large field of view from left to right. Just place yourself in the right place and shoot.

Yes, there are times when physical restrictions dictate “jumping the fence” by using your zoom to take you where your legs won’t go, but you can count those occasions on half the toes of a frostbitten foot. Look at the above shot. What else do you need in the shot that would require a wide-angle zoom to capture? And if the zoom can only open to f/3.5 at its widest aperture, why not use the prime and gain the ability to go all the way to f/1.8 if needed?

Here’s the deal: if you can walk to your shot and use a better, less expensive piece of glass once you get there, why use a zoom? If you can avail yourself of remarkable sharpness and fill your frame with everything you need, free of distortion, and gain extra speed, why use the wideangle? Huh? Huh? Riddle me that, Batman.

THE OOOOH FACTOR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU LONG TO HEAR IT. The audible gasp, the sustained, breathless, collective “oooooh”  from the crowd when the house lights are doused and the holiday tree glows into life in the darkened room. It’s a sonic sample of the extra dimension of emotional engagement that occurs at this time of year, imbuing your photographs with additional firepower. Call it wonder, magic, enchantment, or what you will, but it is there, in greater supply during the season, a tangible thing amidst the bustle and the endless lists of errands.

from the crowd when the house lights are doused and the holiday tree glows into life in the darkened room. It’s a sonic sample of the extra dimension of emotional engagement that occurs at this time of year, imbuing your photographs with additional firepower. Call it wonder, magic, enchantment, or what you will, but it is there, in greater supply during the season, a tangible thing amidst the bustle and the endless lists of errands.

Children are the best barometers of this heightened awareness, since so many of their experiences are first-time experiences. Regular routines become magically unpredictable. Ordinary things take on the golden warmth of tradition. People that are normally on looser orbits circle closer to them for a time. Time expands and contracts. And their faces register it all, from confusion to anticipation. Reading the wonder in a child’s face is truly easy pickings at times like this, but I’m a big believer in catching them while they live their lives, not queueing up for rehearsed smiles or official sittings. Those are important, but the real Santa stuff, the magic fairy dust, gets into the camera when you eavesdrop on something organic.

The wonderful thing is, it’s not big feat to keep a kid distracted during the holidays. They are in a constant state of sensory overload, and so extremely unaware of you that all you have to do is keep it that way. Get reactions to, not re-creations of, their joy. Be a witness, not a choreographer. Stealth is your best friend for seasonal images, and it’s never easier to pull off, so bask a bit in your anonymity.

And, to further feed your own wonder, stay aware of how fleeting all of it is. You are chronicling things that can never, in this exact way, be again. That is, you’re at the very core of why you took photography up in the first place, a way to reboot your enthusiasm.

And it that’s not magic, then I will never know what is…..

FADE TO (ALMOST) BLACK

Sometimes a change in the technical approach to a shot is the only way to freshen an old subject. 1/40 sec., f/1.8, ISO 250, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I KNOW MANY PHOTOGRAPHERS WHO SUBJECT THEMSELVES TO THE DELICIOUS TORTURE, known to authors everywhere,as “publish or perish”, or, in visual terms, the tyranny of shooting something every single day of their lives. There are lots of theories afloat as to whether this artificially imposed discipline speeds one’s development, or somehow pumps their imagination into the bulky heft of an overworked bicep. You must decide, o seekers of truth, what merit any of this has. I myself have tried to maintain this kind of terrifying homework assignment, and during some periods I actually manage it, for a while at least. But there are roadblocks, and one of the chief barriers to doing shot-a-day photography is subject matter, or rather the lack of it.

Let’s face it: even if you live one canyon away from the most breathtaking view on earth or walk the streets of the mightiest metropolis, you will occasionally look upon your immediate environs as a bad rerun of Gilligan’s Island, something you just can’t bear to look at without having a wastebasket handy. Familiarity breeds contempt for some subjects that you’ve visited and re-visited, and so, for me, the only way to re-mix old material is to re-imagine my technical approach to it. This is still a poor substitute for a truly fresh challenge, but it can teach you a lot about interpretation, which has transformed more than a few mundane subjects for me over a lifetime of shuttering (and shuddering).

As an example, a corner of my living room has been one of the most trampled-over crime scenes of my photographic life. The louvered shades which flank my piano can create, over the course of a day, almost any kind of light, allowing me to use the space for quick table-top macros, abstract arrangements of shadows, or still lifes of furnishings. And yet, on rainy /boring days, I still turn to this corner of the house to try something new with the admittedly over-worked material. Lately I have under-exposed compositions in black and white, coming as near a total blackout as I can to try to reduce any objects to fundamental arrangements of light and shadow. In fact, damn near the entire frame is shadow, something which works better in monochrome. Color simply prettifies things too much, inviting the wrong kind of distracted eye wandering in areas of the shot that I don’t think of as essential.

I crank the aperture wide open (or nearly) to keep a narrow depth of field, which renders most of the image pretty soft. I pinch down the window light until there is almost no illumination on anything, and allow the ISO to float around at least 250. I get a filmic, grainy, gauzy look which is really just shapes and light. It’s very minimalistic, but it allows me to milk something fresh out of objects that I’ve really over-photographed. If you believe that context is everything, then taking a new technical approach to an old subject can, in fact, create new context. Fading almost to black is one thing to try when you’re stuck in the house on a rainy day.

Especially if there’s nothing on TV except Gilligan.

ON THE SOFT SIDE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE WORLD’S FIRST MOVIE STUDIO WAS A TARPAPER SHACK ON A TURNTABLE. Dubbed by Thomas Edison’s techies as “The Black Maria” (as ambulances were grimly named back at the time), the structure rotated to take advantage of wherever sunlight was available in the California sky, thus allowing the film crew to extend its daily shooting schedule by more than half in the era of extremely slow film stocks. Eventually artificial light of sufficient strength was developed for the movies, and actors no longer had to brave motion sickness just to rescue fair damsels. So it goes.

More than a century hence, some photographers actually have to be reminded to use natural light, specifically window light, as a better alternative to studio lights or flash units. Certainly anyone who has shot portraits for a while has already learned that window light is softer and more diffuse than anything you can plug in, thus making it far more flattering to faces (as well as forgiving of , er, flaws). It’s also good to remember that it can lend a warming effect to an entire room, on those occasions where the room itself is a kind of still life subject.

Your window light source can be harsher if the sun is arching over the roof of your building toward the window (east to west), so a window that receives light at a right angle from the crossing sun is better, since it’s already been buffered a bit. This also allows you to expose so that the details outside the window (trees, scenery, etc.) aren’t blown out, assuming that you want them to be prominent in the picture. For inside the window, set your initial exposure for the brightest objects inside the room. If they aren’t white-hot, there is less severe contrast between light and dark objects, and the shot looks more balanced.

I like a look that suggests that just enough light has crept into the room to gently illuminate everything in it from front to back. You’ll have to arrive at your own preferred look, deciding how much, if any, of the light you want to “drop off” to drape selective parts of the frame in shadow. Your vision, your choice. Point is, natural light is so wonderfully workable for a variety of looks that, once you start to develop your use of it, you might reach for artificial light less and less.

Turns out, that Edison guy was pretty clever.

SOMETIMES THE MAGIC WORKS…

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE DIGITAL ERA IN PHOTOGRAPHY HAS SMASHED DOWN THE DOORS TO WHAT WAS ONCE A FAIRLY EXCLUSIVE CLUBHOUSE, a select brotherhood (or sisterhood) of wizards who held all the secrets of their special science. The wizzes got great results and created “art. The rest of us slobs just took snapshots.

Today, the emphasis in photographic method has shifted from understand, study and do, to do, understand and, maybe study. We are now a nation of confident what-the-hellers. Try it, and if it don’t work, try something else. In some ways, this is a shift away from intellect and toward instinct. We are all either a little less technically aware of why the magic works, or completely indifferent to the underlying processes at work. You can all huddle together and decide whether this is a good thing.

Which, by way of introduction, is a way of saying that sometimes you do something that flies in the face of science or sense and it still works out. To illustrate, let us consider the humble polarizing filter, which, for me, is more important than many of the lenses I attach it to. It richens colors, cuts reflections, and eliminates the washed-out look of shots taken in intense daylight sun, as well as taming the squinty haze caused by smog. Or, if you want the Cliff’s Notes version, it makes skies blue again.

Now there is a “proper” way to get top results with a polarizer. Make an “L” with your index finger and thumb, finger pointing straight up. UP in this example is the position of the sun overhead, and your thumb, about 90 degrees opposed to your finger, roughly represents your camera’s lens. The closer to 90 degrees that “L” is, the more effective the filter will be in reducing glare and boosting color. Experts will tell you that using a polarizer any other way will deliver either small or no results. That’s it. Gospel truth, science over superstition, settled argument.

That’s why I can’t explain the two pictures in this post, taken just after sunrise, both with and without the filter. In the first, seen at left, Los Angeles’ morning haze is severe, robbing the rooftop image of contrast and impact. In the second, shown above, the sky is blue, the colors are intense and shadows are really, well, shadows. But consider: not only is the sun too low in the sky for the filter’s accepted math to work, I am standing inside a hotel room, and yet the filter still does its duty, and all is right with the world. If I had followed and obeyed package directions, this shot should not have worked. That means if I were to pre-empt myself, defaulting to what is scientific and “provable”, and ignoring my instinct, I would not even have tried this image. The takeaway: perhaps I need to preserve just enough of the ignorant noobie I once was, and let him take the wheel sometimes, even if the grown-up in me says it can’t be done.

The yin and yang wrestling match between intellect and instinct is essential to photography. Too much science and you get sterility. Too much gut and you get garbage. As usual,the correct answer is provided by what you are visualizing. Here. Now. This moment.

WAIT FOR IT…..

by MICHAEL PERKINS

SUNDAY MORNINGS AT THE LOS ANGELES COUNTY MUSEUM OF ART ARE A GAGGLE OF GIGGLES, a furious surge of activity for, and by, little people. Weekly craft workshops at LACMA are inventive, inclusive, and hands-on. If you can cut it, fold it, glue it, paint it, or assemble it, it’s there, with booths that feature encouraging help from slightly larger people and smiles all around. It is a fantastic training ground as well for photographing kids in their natural element.

A recent Sunday featured the rolling out of long strips of art paper into rows along one of the common sidewalks, with museum guides on bullhorn exhorting the young to create their own respective visions with paint and brush. The event itself was rich in possibility, as a hundred little dramas and crises unfolded along the wide, white canvasses. Here a furrowed brow, there an assist from Mom. Fierce concentration. Dedication of purpose. Sunshaded Picassos-in-waiting weighing the use of color, stroke, concept. A mass of masters, and plenty of chances for really decent images.

Most of these events are as fast as they are furious, and so, during their brief duration, you can go from photographic cornucopia to….where did everybody go? Sometimes it’s over so quickly that it’s really tempting to treat the entire thing like low-hanging fruit: a ton of kids pass before your eyes in a few minutes’ time, and you have only to stand and click away. Thing is, I’m a lifelong believer in arriving early and leaving late, simply because the unexpected bit of gold will drop into your lap when you troll around before the beginning or after the end of things. In the case of this museum “paint-in”, the participants scampered on to the next project in one big sweep, leaving their artwork behind like a ruined battlefield. And then, miracle of miracles, one lone girl wandered into the near center of this huge Pollack panorama and sat herself down. The event was over but the vibe was revived. I whispered thank you, photo gods, and framed to use the paintings as a visual lead-in to her. It couldn’t have been simpler, luckier, or happier.

When the “stage” on public events is being either set or struck, there are marvelous chances to peer a bit deeper.People are typically relaxed, less guarded. The feel of everything has an informality, even an intimacy. And sometimes a small child brings the gift of her spirit into the frame, and you remember why you keep doing this.

AS DIFFERENT AS DAY AND NIGHT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY OFTEN PRESENTS ITSELF AS A SUDDEN, REACTIVE OPPORTUNITY, a moment in time where certain light and compositional conditions seem ripe for either recording or interpreting. In such cases there may be little chance to ponder the best way to visualize the subject at hand, and so we snap up the visualization that’s presented in the moment. It’s the kind of use-it-or-lose-it bargain we’re all acquainted with. Sometimes it yields something amazing. Other times we do the best with what we’re handed, and it looks like it.

Having the option to shape light as we like takes time and deliberate planning, as anyone who has done any kind of studio set-up will attest. The stronger your conception to start with, the better chance you have of devising a light strategy for making that idea real. That’s why I regard light painting, which I’ve written about here several times, as a great exercise in building your image’s visual identity in stages. You slow down and make the photograph evolve, working upwards from absolute darkness.

Shock-Top, 2014. Light-painted with a hand-held LED over the course of a six-second exposure, at f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

To refresh, light painting refers to the selective handheld illumination of subjects for a particular look or effect. The path that your flashlight or LED takes across your subject’s contours during a tripod-mounted time exposure can vary dramatically, based on your moving your light source either right or left, arcing up or down, flickering it, or using it as a constant source. Light painting is different from the conditions of, say, a product shoot, where the idea is to supply enough light to make the image appear “normal” in a daytime orientation. Painting with light is a bit like wielding a magic wand, in that you can produce an endless number of looks as you develop your own concept of what the final image should project in terms of mood. It isn’t shooting in a “realistic” manner, which is why the best light painters can render subjects super-real, un-real, abstract or combinations of all three. Fact is, the most amazing paint-lit photos often completely violate the normal paths of natural light. And that’s fine.

In light painting, I believe that total darkness in the space surrounding your central subject is as important a compositional tool as how your subject itself is arranged. As a strong contrast, it calls immediate and total attention to what you choose to illuminate. I also think that the grain, texture and dimensional quality of the subject can be drastically changed by altering which parts of it are lit, as in the shock of wheat seen here. In daylight, half of the plant’s detail can be lost in a kind of brown neutrality, but, when light painted, its filaments, blossoms and staffs all relate boldly to each other in fresh ways; the language of light and shadow has been re-ordered. Pictorially, it becomes a more complex object. It’s actually freed from the restraints of looking “real” or “normal”.

Developed beyond its initial novelty, light painting isn’t an effect or a gimmick. It’s another technique for shaping light, which is really our aim anytime we take off our lens caps.

DESTINATION VS. JOURNEY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE A WANDERING EYE. Not due to muscular weakness or marital infidelity, but to a malady particular to long-time photographers. After decades of shoots big and little, I find that I am looking for pictures nearly everywhere, so much so that, what appears to many normal people to be formless space or unappealing detail might be shaping up in my mind as My Next Project. The non-obvious sings out ever louder to me as I age, and may find its way into my pictures more often than the Celebrated Scenic Wonder, the Historically Important Site or the Big Lights In The Sky that attract 99% of the photo traffic in any given locality. Part of this has to do with having been disappointed in the past by the Giant Whatsis or whatever the key area attraction is, while being delightfully surprised by little things that, for me, deserve to be seen, re-seen, or testified to.

This makes me a lousy traveling companion at times, since I may be fixated on something merely “on the way” to what everyone else wants to see. Let’s say we’re headed to the Great Falls. Now who wants to photograph the small gravel path that leads to the road that leads to the Great Falls? Well, me. As a consequence, the sentences I hear most often, in these cases, are variations on “are you coming?“, “what are you looking at?” or, “Oh my God, are you stopping again????”.

Thing is, some of my favorite shots are on staircases, in hallways, around a blind corner, or the Part Of The Building Where No One Ever Goes. Photography is sometimes about destination but more often about journey. That’s what accounts for the staircase above image. It’s a little-traveled part of a museum that I had never been in, but was my escape the from gift shop that held my wife mesmerized. I began to wonder and wander, and before long I was in the land of Sir, We Don’t Allow The Public Back Here. Oddly, it’s easier to plead ignorance of anything at my age, plus no one wants to pick on an old man, so I mutter a few distracted “Oh, ‘scuse me”s and, occasionally, walk away with something I care about. Bonus: I never have any problem shooting as much as I want of such subjects, because, you know, they’re not “important”, so it’s not like queueing up to be the 7,000th person of the day doing their take on the Eiffel Tower.

Now, this is not a foolproof process. Believe me, I can take these lesser subjects and make them twice as boring as a tourist snap of a major attraction, but sometimes….

And when you hit that “sometimes”, dear friends, that’s what makes us raise a glass in the lobby bar later in the day.

SHOW, DON’T TALK

Got a feeling inside (can’t explain)

It’s a certain kind (can’t explain)

I feel hot and cold (can’t explain)

Yeah, down in my soul, yeah (can’t explain)—–Pete Townshend

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY NEEDS MORE ARTISTS AND FEWER ART CRITICS. Period, full stop.

When it comes to imaging, those who can, do, and those who can’t, curate shows. Or pontificate on things they had no hand in creating. It’s just human nature. Some of us build skyscrapers and some of us are “sidewalk superintendents”, peering through the security fencing to cluck our tongues in scorn, because, you know, those guys aren’t doing it right.

Even wonderful pioneers in “appreciation” like the late John Szarkowski, one of the first curators of photography at the New York Museum of Modern Art , and a tireless fighter for the elevation of photography to a fine art, often tossed up bilious bowlfuls of word salad when remarking on the work of a given shooter. As essays his remarks were entertaining. As explanations of the art, they were redundant.

This human need to explain things is vital if you’re trying to untie the knotted language of a peace treaty or complete a chemical equation, but it just adds lead boots to the appreciation of photography, which is to be seen, not read about (sassy talk for a blogger, no? Oh, well). No amount of captioning (even by the artist) can redeem a badly conceived photograph or make it speak more clearly. It all begins to sound like so many alibis, so many “here’s what I was going for” footnotes. Photography is visual and visceral. If you reached somebody, the title of the image could be “Study #245” and it still works. If not, you can append the biggest explanatory screed since the Warren Report and it’s still a lousy photo.

I’m not saying that all context is wrong in regard to a photo. Certainly, in these pages, we talk about motivation and intention all the time. However, such tracts can never be used to do the actual job of communicating that the picture is supposed to be doing. Asked once about the mechanics of his humor, Lenny Bruce spoke volumes by replying,” I just do it, that’s all.” I often worry that we use captioning to push a viewer one way or another, to suggest that he/she react a certain way, or interpret what we’ve done along a preferred track. That is the picture’s task, and if we fail at that, then the rest is noise.

REVENGE OF THE ZOO

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PURISTS IN THE ANIMAL PHOTOGRAPHY GAME OFTEN DISPARAGE IMAGES OF BEASTIES SHOT AT ZOOS, citing that they are taken under “controlled conditions”, and therefore somewhat less authentic than those taken while you are hip-deep in ooze, consumed by insects, or scratching any number of unscratchable itches. Editors won’t even consider publishing pics snapped at the local livestock lockup, as if the animals depicted in these photos somehow surrendered their union cards and are crossing a picket line to work as furry scabs .

This is all rubbish of course, part of the “artier-than-thou” virus which afflicts too great a percentage of photo mavens across the medium. As such, it can be dismissed for the prissy claptrap that it is. Strangely, the real truth about photographing animals in a zoo is that the conditions are anything but controlled.

We’ve all been there: negotiating focuses through wire mesh, dealing with a mine field of wildly contrasting light, and, in some dense living environments, just locating the ring-tailed hibiscus or blue-snouted croucher. Coming away with anything can take the patience of Job and his whole orchestra.Then there’s the problem of composing around the most dangerous visual obstacle, a genus known as Infantis Terribilis, or Other People’s Kids. Oh, the horror.Their bared teeth. Their merciless aspect. Their Dipping-Dots-smeared shirts. Brrr…

In short, to consider it “easy” to take pictures of animals in a zoo is to assert that it’s a cinch to get the shrink wrap off a DVD in less than an afternoon….simply not supported by the facts on the ground.

So, no, if you must take your camera to a zoo, shoot your kids instead of trying to coax the kotamundi out of whatever burrow he’s…burrowed into. Better yet, shoot fake animals. Make the tasteless trinkets, overpriced souvies and toys into still lifes. They won’t hide, you can control the lighting, and, thanks to the consistent uniformity of mold injected plastic, they’re all really cute. Hey, better to come home with something you can recognize rather than trying to convince your friends that the bleary, smeary blotch in front of them is really a crown-breasted, Eastern New Jersey echidna.

Any of those Dipping Dots left?