HEADSTONES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF ARCHITECTURAL PROJECTS, AT THEIR BIRTHS, REPRESENT A KIND OF FAITH, then the demise of buildings likewise signals a sort of death, a loss of belief, an admission of failure. Our new societies break ground on developments in one generation only to see them wither to silence in the next, a cycle of boom and bust that somehow has become the rhythm of modern life.

Viewing the ruins that result from all our once-bright industrial dreams through the lens of a camera creates a peculiar kind of commentary, less specific but more emotionally immediate than a written editorial or essay. The first uses of photography as chronicles of urban life were largely neutral, merely recording city vistas, monuments, cathedrals, scenic wonders. It took the aftermath of World War One and the Great Depression to infuse architectural photos with the sting of commentary, as if the photographer was asking, what have we done? What is all this for?

In the 1930’s, there was a quick segue from the New Deal’s programs for documenting relief programs to a new breed of socially activist shooters like Walker Evans and Margaret Bourke-White, who showed us both the human and architectural faces of despair. Suddenly closed businesses, shabby tenements, and collapsed infrastructures became testimony on what we were doing wrong, of the horrific gap between our dreams and our deeds.

In every town across America, photographers continue to search for the headstones of our lost hopes, the factories, foundries, and dashed ventures that define who we hoped to be, and how things went wrong. It’s not a photography of hopelessness, however, but a dutiful reminder that actions have consequences, for good or ill. Turning our eyes, and lenses, to the stories left behind by the earlier versions of ourselves is a way of measuring, of keeping score on what kind of world we desire. The headstones bear clear inscriptions. Deciphering them is the soul of photography.

SURVEYING THE SURFACE WORLD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

COLOR, IN A PHOTOGRAPH, IS OFTEN THOUGHT OF IN OVER-SIMPLIFIED TERMS, as if there were one even tone to every part of everything we capture, what I call the “paint roller” school of thought. One of the reasons color was so long in development in the film era was because it had to become accurate at measuring the myriad inconsistencies in the hues of objects. Consider the wide range of pinks, reds, even blues in the contours of a single human face. There is no “flesh” color outside of a box of Crayolas, and color photography has evolved over time to deliver the real, if tricky, inch-to-inch changes in the tone of every kind of surface.

Skin or wood, plastic or metal, color changes frequently over the surface of an object, and good photographers learn how to get stunning effects through application of that principle. One subject which can deliver dramatic results with little effort is the urban building, primarily the metal urban building. Many of the metals used in construction are actually alloys, and so they already contain color elements of their constituent ingredients.

Metal alloys produce wide color variations under the right lighting conditions. 1/50 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100-24mm.

I try to shoot alloys in fairly indirect light, as this amps up the shimmer and gloss of their surfaces in a way straight-on lighting tends to bleach out or subdue. I also set my camera for whatever “vivid” color setting it allows, since more color information means more clear reproduction of the subtle changes in tone from, say, one end of a section of metal to the other. In post-production, I will often play with contrast and temperature to enhance whatever I want to present in the image’s overall color mood.

Metal can run the gamut from grey to blue to green to pure white, and learning how to place those shades where you want them can add dimension to your photos.

PHOTOSHOP THE MOMENT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S BEYOND POINTLESS TO PREACH OF “PURITY” when it comes to photographic technique, although the argument springs up whenever the idea of manipulation comes up. It’s not even a new squabble. No sooner had science given the world a way to record reality with a machine than artists began tweaking, twisting, and torturing effects out of the camera that could only be done by deliberate intervention. So much for reality. In fact, photography’s first half-century boasts a rainbow of spectacular effects, undertaken precisely to undermine or improve upon the real world.

No, it’s about a century and a half too late to worry about whether people will alter their photographs and high time we explored what kind of manipulations are best for the overall impact of an image. I personally prefer to “photoshop the moment”, or to calculate what I need in a picture during the taking of it. I truly feel that, in most post-shutter tweaking, you lose an intangible something that might have made real magic if factored into the same-time making of the picture. The best thing about planning is, it gets easier to get better effects from simpler things, things that seem to work better for the picture if you design them into the shot rather than adding them later.

Take the ridiculously obvious tweak done in the above picture. 90% of the final photo here is in the composition of the shot, framing the entrance of this wonderful old house in the arch of its outer gate. The sunlight is perfect for the back two-thirds of the picture, but, given the position of the sun in late afternoon on that particular street, my first shot tended to render the arched topiary very dark, nearly a silhouette. Thing is, I really wanted the entire image to have a kind of fairy tale quality. I needed an intervention.

Easy fix. I walked back a few steps to make sure that my flash was just powerful enough to pop a hot green into the arch, yet too faint to illuminate anything else. As a result, the color you see here is not goosed up after the fact. I exposed for the house in the background and the fill flash made the foreground hues as bright as the stuff in back. Again, as planning goes, thus wasn’t the D-Day invasion. I just needed to make one simple change to solve my problem, and the fact that I did it during the original making of the picture made me feel like I was in charge of the project to a greater degree.

PRECISION C, FEELING A

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF YOU TRAVEL ENOUGH, YOU’LL DISCOVER THAT, OF ALL THE TIMES YOU WANT to take a photograph, there are only a few times in which acceptable picture-making conditions are actually present. For all too many subjects that you experience on the fly, only a small percentage of them allow you the time, light, information or opportunity to do your best. And yet…you do what you must, and trust to instinct and chance for the rest.

Immediately upon arrival in a new town, my mind goes to one task, and one task only: sticking anyone else with the driving, so I can take potshots out the car window as I see fit. I have no need to head the posse or lead the expedition. You be in charge, big man. Get me to the hotel and leave me to make as many attempts as possible to put something worthwhile inside my camera.

Of course, this means that I have to pay at least some attention to how insanely you drive…shortcuts, rapid swerves, jolts and all. And, hey, couldn’t you have lingered a millisecond longer after the light went green, since I was just about to create an immortal piece of street art, instead of the muscular spasm I now have frozen forever on my memory card?

When shooting from a car, there are lots of things that go out the window (sorry), among them composition, exposure, stability, and, most generally, focus. En route to L’Enfant Plaza in Washington D.C. a few years ago, I fell in love with the funky little tobacco shop you see here. The colors, the woodwork, the look of yesteryear, it all spoke to me, and I had to have it. So I shot it at 1/250 sec, more than fast enough to freeze nearly anything in focus, unless by “nearly anything” you mean something that you’re not careening past at the pace of the average Tijuana taxicab. Result? Well, I didn’t wind up with unspeakable blur, but it’s certainly softer than I wanted. Of course, I could have offered an acceptable alibi for the shot, something based on some variant like, “of course, I meant to do that”, that is, until I outed myself in this post, just now.

But we try. Sometimes it’s the fleeting nature of things seen from car windows that make the attempt even more appealing than the potential result. In that instant, it seems like nothing’s more important than trying to take a picture. That picture. I won’t get ’em all. But as long as I live, I hope I never lose that mad, what-the-hell urge to just go for it.

So okay, seeing as this is a photo of a tobacco shop, this is where one of you cashes in the “close, but no cigar” gag line.

Go ahead, I’ll give you that one.

DOCUMENTARY OR DRAMA?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I RECENTLY HEARD AN INTERESTING CRITIQUE OF A DRAMATIC CONTENDER for Best Film in the 2015 Oscar race. The critic in question complained that the film in question (Boyhood) was too realistic, too inclusive of banal, everyday events, and thus devoid of the dynamics that storytellers use to create entertainment. His bottom line: give us reality, sure, but, as the Brits say, with the boring bits left out.

If you’re a photographer, this argument rings resoundingly true. Shooters regularly choose between the factual documentation of a scene and a deliberate abstraction of it for dramatic effect. We all know that, beyond the technical achievement of exposure, some things that are real are also crashingly dull. Either they are subjects that have been photographed into meaninglessness (your Eiffel Towers, your Niagara Fallses) or they possess no storytelling magic when reproduced faithfully. That’s what processing is for, and, in the hands of a reliable narrator, photographs that remix reality can become so compelling that the results transcend reality, giving it additional emotive power.

This is why colors are garish in The Wizard Of Oz, why blurred shots can convey action better than “frozen” shots, and why cropping often delivers a bigger punch and more visual focus than can be seen in busier compositions. Drama is subject matter plus the invented contexts of color, contrast, and texture. It is the reassignment of values. Most importantly, it is a booster shot for subjects whose natural values under-deliver. It is not “cheating”, it is “realizing”, and digital technology offers a photographer more choices, more avenues for interpretation than at any other time in photo history.

The photo at left was taken in a vast hotel atrium which has a lot going for it in terms of scope and sweep, but which loses some punch in its natural colors. There is also a bit too much visible detail in the shot for a really dramatic effect. Processing the color with some additional grain and grit, losing some detail in shadow, and amping the overall contrast help to boost the potential in the architecture to produce the shot you see at the top of this post. Mere documentation of some subjects can produce pretty but flaccid photos. Selectively re-prioritizing some tones and textures can create drama, and additional opportunity for engagement, in your images.

25, 50, T, B

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS A PART OF WILSHIRE BOULEVARD IN LOS ANGELES that I have been using for a photographic hunting ground for over ten years, mostly on foot, and always in search of the numerous Art Deco remnants that remain in the details of doors, window framings, neighborhood theatres and public art. Over the years, I have made what I consider to be a pretty thorough search of the stretch between Fairfax and LaBrea for the pieces of that streamlined era between the world wars, and so it was pretty stunning to realize that I had been repeatedly walking within mere feet of one of the grand icons of that time, busily looking to photograph….well, almost anything else.

A few days ago, I was sizing up a couple framed in the open window of a street cafe when my composition caught just a glimpse of black glass, ribbed by horizontal chrome bands. It took me several ??!?!-type minutes to realize that what I had accidentally included in the frame was the left edge of the most celebrated camera in all of Los Angeles.

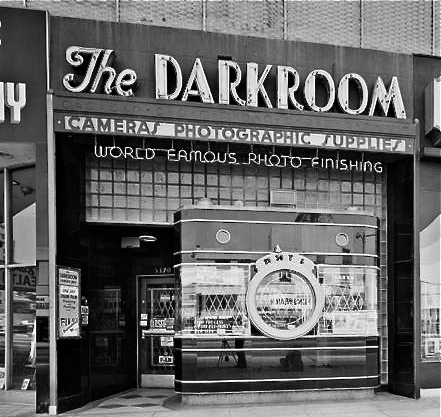

Opened in the 1930’s, the Darkroom camera shop stood for decades at 5370 Wilshire as one of the greatest examples of “programmatic architecture”, that cartoony movement that created businesses that incorporated their main product into the very structure of their shops, from the Brown Derby restaurant to the Donut Hole to, well, a camera store with a nine-foot tall recreation of an Argus camera as its front facade.

The surface of the camera is made of the bygone process known as Vitrolite, a shiny, black, opaque mix of vitreous marble and glass, which reflects the myriad colors of Los Angeles street life just as vividly today as it did during the New Deal. The shop’s central window is still the lens of the camera, marked for the shutter speeds of 1/25th and 1/50th of a second, as well as T (time exposure) and B (bulb). A “picture frame” viewfinder and two film transit knobs adorn the top of the camera, which is lodged in a wall of glass block. Over the years, the store’s original sign was removed, and now resides at the Museum of Neon Art in Glendale, California, while the innards of the shop became a series of restaurants with exotic names like Sher-e-Punjab Cuisine and La Boca del Conga Room. Life goes on.

True to the ethos of L.A. fakes, fakes of fakes, and recreations of fake fakes, the faux camera of The Darkroom has been reproduced in Disney theme parks in Paris and Orlando, serving as…what else?….a camera shop for visiting tourists, while the remnants of the original storefront enjoy protection as a Los Angeles historic cultural monument. And, while my finding this little treasure was not quite the discovery of the Holy Grail, it certainly was like finding the production assistant to the stunt double for the stand-in for the Holy Grail.

Hooray for Hollywood.

THE ROMANCE OF RUIN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I TYPICALLY SHY AWAY FROM USING OR CREATING PHOTOGRAPHS as illustrations of work in another medium. Writers don’t try to caption my images, and I don’t presume, for the most part, to imagine visuals for their works. As both photographer and writer, I am sympathetic to the needs and limits of both graphic and written mediums. And still, there are rare times when a combination of events seem to imply a collaboration of sorts between the two means of storytelling. I made such an attempt a while back in these pages, in the grip of nostalgia for railroads, and so here goes with another similar experiment.

Last week, during a blue mood, I sought out, as I often do, songs by Sinatra, since only Frank does lonely as if he invented the concept, conveying loss with an actor’s gift for universality. I stumbled across a particularly poignant track entitled A Cottage For Sale, which I sometimes can’t listen to, even when I need its quiet, desolate description of a dream gone wrong. So, that song was the first seed in my head.

Last week, during a blue mood, I sought out, as I often do, songs by Sinatra, since only Frank does lonely as if he invented the concept, conveying loss with an actor’s gift for universality. I stumbled across a particularly poignant track entitled A Cottage For Sale, which I sometimes can’t listen to, even when I need its quiet, desolate description of a dream gone wrong. So, that song was the first seed in my head.

Seed two came a few days later, when I was shortcutting through one of those strange Phoenix streets where suburban and rural neighborhoods collide with each other, blurring the track of time and making the everyday unreal. I saw the house you see here, a place so soaked in despair that it seemed to cry out for the lyrics of Frank’s song. Again, I’m not trying to provide the illustration for the song, just one man’s variation. So, for what it’s worth:

Is lonely and silent, the shades are all drawn,

And my heart is heavy as I gaze upon

A cottage for sale

Where you planted roses,the weeds seem to say,

“A cottage for sale”.

But when I reach a window, there’s empty space.

But no one is waiting for me any more,

The end of the story is told on the door.

A cottage for sale.

COME EARLY / STAY LATE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PUBLIC SPACES OFTEN LOSE THEIR POWER AS GRAND DESIGNS once they actually are occupied by the public. If you have ever leafed through books of architectural renderings, the original drawings for squares, plazas, office buildings or other mass gathering places, the elegance of their patterns is apparent in a way that they cease to be, once they are teeming with commuters or customers.

This doesn’t mean that humans “spoil” the art of architecture, however, the overlay of drama and tension created by the presence of huge hordes of people definitely distracts from an appreciation of the beauty that is so clean and clear in a place’s sketch phase. Photographically, people as design objects tend to steal the scene, if you will, making public settings less dramatic in some ways. That’s why I like to make images of such locales when they are essentially empty, since it forces the eye to see design as the dominant story in the picture. I suppose that I’m channeling the great designers and illustrators that influenced me as a young would-be comic book artist. It’s a matter of emphasis. While other kids worked on rendering their superheroes’ muscles and capes correctly, I wanted to draw Metropolis right.

I recently began driving to various mega-resorts in the Phoenix, Arizona area to capture scenes in either early morning or late afternoon. Some are grand in their ambition, and more than a few are plain over-the-top vulgar, but sometimes I find that just working with the buildings and landscaping as a designer might have originally imagined them can be surprising. Taking places which were meant to accommodate large gatherings of people, then extracting said people, forces the eye to align itself with the original designer’s idea without compromise. Try it, and you may also find that coming early or staying late at a public area gives you a different photographic perspective on a site. At any rate, it’s another exercise in re-seeing, or forcing yourself to visualize a familiar thing eccentrically.

EATS

You want fries with that? Blythe, California’s Courtesy Coffee Shop. 1/320 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN HIS WONDERFUL 1960 ROAD JOURNAL, TRAVELS WITH CHARLEY, John Steinbeck, author of The Grapes Of Wrath, Of Mice And Men and other essential American novels, laments the passing of a kind of America in much the same way that a roving photographer might. “I wonder”, he wrote as he motored through one vanishing frontier after another, “why progress looks so much like destruction.” That’s a sentiment that many a shooter has experienced as he pans his viewfinder over the various fading scenes of a constantly changing nation. Steinbeck sang his ode to these vaporized hopes on the printed page. We freeze their vanishings in a box.

However, capturing changes in a rambling big hulk of a country encompasses more than merely mourning the loss of a forest or the paving of a paradise. Photographic testimony needs to be made on the evolution of even the America we feel is vulgar, or ugly, or strange, as well as on the disappearance of the buffalo. There can be a visual poignancy in seeing even our strangest, most misbegotten features dissolving away, and great picture opportunities exist in both the beautiful and the tawdry.

One of the strangest visual cultures that we see cracking and peeling away across the USA is the culture of eating. The last hundred years have seen the first marriage between just taking a meal and deliberately creating architecture that is aimed at marketing that process. Neon signs, giant Big Boys shouldering burgers, garish arrows pointing the way to the drive-through….it’s crude and strange and wonderful, all at the same time, and even more so as its various icons start to fall by the wayside.

The Courtesy Coffee Shop, baking in the desert sun just beyond the Arizona border in Blythe, California, is one such odd rest stop. Its mid-century design, so edgy at the start of space ships and family station wagons, creaks now with age, a museum to cheeseburgers and onion rings of yesteryear. Its waitresses look like refugees from an episode of Alice. It recalls the glory days of flagstone and formica. And they’ve been doing the bottomless coffee cup thing there since the Eisenhower administration.

Steinbeck, were he on the road again today, might not give a jot about the passing of the Courtesy into history, but restaurants can be interesting mile markers on the history trail just as much as mountains and lakes. Besides, when’s the last time a mountain whipped up a Denver omelet for you?

DETAILS, DETAILS

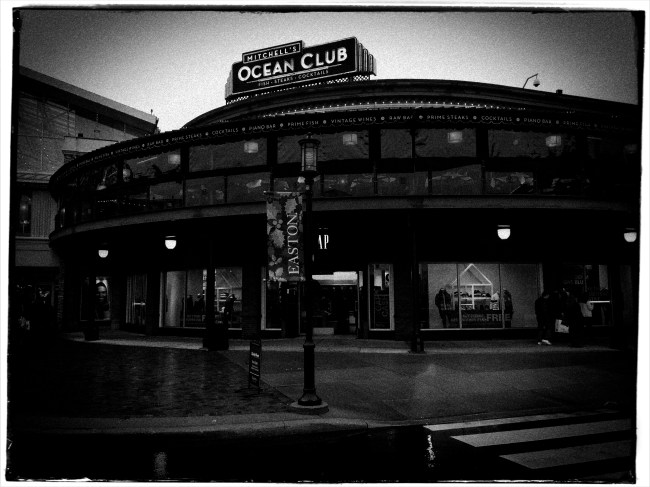

Moody, but still a bit too tidy. Black and white by itself wasn’t enough to create the atmosphere I wanted.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVEN THOUGH MOST GREAT PHOTOGRAPHERS PROCLAIM that any “rules” in their medium exist only to be broken, it’s often tough to chuck out regulations that have served you well over a lifetime of work. Once you get used to producing decent images through the repetition of habit, it takes extra nerve to take yourself outside your comfort zone, even if it means adding impact to your shots. You tend not to think of rules as arbitrary or confining, but as structural pillars that keep the roof from falling in.

That’s why it’s a good exercise to force yourself to do something that you feel is a bad fit for your style, lest your approach to everything go from being solid to, well, fossilized. If you hate black and white, make yourself shoot only monochrome for a week. If you feel cramped by square framing, make yourself work exclusively in that compositional format, as if your camera were incapable of landscape or portrait orientations. In my own case, I have to pry my brain away from an instinctual reliance on pinsharp focus, something which part of me fears will lead to chaos in my images. However, as I occasionally force myself to admit, sharp ain’t everything, and there may even be some times when it will kill, or at least dull, a picture.

With post-processing such an instantaneous, cheap, and largely effortless option these days, there really isn’t any reason to not at least try various modes of partial focus just to see where it will lead. Take what you believe will work in terms of the original shot, and experiment with alternate ways of interpreting what you started with.

In the shot at the top of this post, I tried to create mood in a uniquely shaped fish house with monochrome and a dour exposure on a nearly colorless day. Thing is, the image carried too much detail to be effectively atmospheric. The place still looked like a fairly new, fairly spiffy eatery located in an open-air shopping district. I wanted it to look like a worn, weathered joint, a marginal hangout that haunted the wharf that its seafood theme and design suggested. I needed to add more mood and mystery to it, and merely shooting in black & white wasn’t going to get me there, so I ran the shot through an app that created a tilt-shift focus effect, localizing the sharpness to the rooftop sign only and letting the rest of the structure melt into murk.

It shouldn’t be hard to skate around a rule in search of an image that comes closer to what you see in your mind, and yet it can require a leap of faith. Hard to say why trying new things spikes the blood pressure. We’re not heart surgeons, after all, and no one dies if we make a mistake.Anyway, you are never more than one click away from your next best picture.

HAPPY OLD YEAR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

The White Rabbit put on his spectacles. ‘Where shall I begin, please your Majesty?’ he asked. ‘Begin at the beginning,’ the King said gravely, ‘and go on till you come to the end: then stop.’

IN A SIMPLER WORLD, THE KING OF HEARTS, quoted above in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, would be perfectly correct. All things being equal, the beginning would be the best place to begin. But, in photography, as in all of life, we are always coming upon a series of beginnings. Learning an art is like making a lap in Monopoly. Just when we think we are approaching our destination, we pass “Go” again, and find that one man’s finish line is another man’s starting gate. Photography is all about re-defining where we are and where we need to be. We always begin, and we never finish.

As 2014 comes to an intersection (I can’t really say ‘a close’ after all that, can I?), it’s normal to review what might be either constant, or changed, about one’s approach to making pictures. That, after all, is the stated aim of this blog, making The Normal Eye more about journey than destination. And so, all I can do in reviewing the last twelve months of opportunities or accidents is to try to identify the areas of photography that most define me at this particular juncture, and to reflect on the work that best represents those areas. This is not to say I’ve gained mastery, but rather that I’m gaining on it. If my legs hold out, I may get there yet. But don’t count on it.

The number twelve has become, then, the structure for the blog page we launch today, called (how does he think of these things?) 12 for 14. You’ll notice it as the newest gallery tab at the top of the screen. There is nothing magical about the number by itself, but I think forcing myself to edit, then edit again, until the thousands of images taken this year are winnowed down to some kind of essence is a useful, if ego-bruising, exercise. I just wanted to have one picture for each facet of photography that I find essentially important, at least in my own work, so twelve it is.

Light painting, landscape, HDR, mobile, natural light, mixed focus, portraiture, abstract composition, all these and others show up as repeating motifs in what I love in others’ images, and what I seek in my own. They are products of both random opportunity and obsessive design, divine accident and carefully executed planning. Some are narrative, others are “absolute” in that they have no formalized storytelling function. In other words, they are a year in the life of just another person who hopes to harness light, perfect his vision, and occasionally snag something magical.

So here we are at the finish line, er, the starting gate, or….well, on to the next picture. Happy New Year.

PRESERVING THE PERCEPTION

Your memory tells you that this space is more like a “library” than a “drug store”, unless you live in a much nicer neighborhood than mine.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS AN OLD ADVERTISING MAXIM that the first person to introduce a product to market becomes the “face” of all versions of that product forever, no matter who else enters as a competitor. Under this thinking, all soda generically becomes a Coke; all facial tissues are Kleenexes: and no matter who made your office copier, you use it to make…Xeroxes. The first way we encounter something often becomes the way we “see” it, maybe forever.

Photography is shorthand for what takes much longer to explain verbally, and sometimes the first way we visually present something “sticks” in our head, becoming the default image that “means” that thing. Architecture seems to send that signal with certain businesses, certainly. When I give you Doric columns and gargoyles, you are a lot likelier to think courthouse than doghouse. If I show you panes of reflective glass, large open spaces and stark light fixtures, you might sift through your memory for art gallery sooner than you would for hardware store. It’s just the mind’s convenient filing system for quickly identifying previous files, and it can be a great tool for your photography as well.

As a shooter, you can sell the idea of a type of space based on what your viewer expects it to look like, and that could mean that you shoot an understated or even tightly composed, partial view of it, secure in the knowledge that people’s collective memory will provide any missing data. Being sensitive to what the universally accepted icons of a thing are means you can abbreviate or abstract its presentation without worrying about losing impact.

Photography can be at its most effective when you can say more and more with less and less. You just have to know how much to pare away and still preserve the perception.

TESTIMONY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY WAS IN ITS INFANCY WHEN IT WAS FIRST PRESSED INTO SERVICE as a reportorial tool, a way of bearing witness to wars, disasters, and the passing parade of human folly and fashion. Since that time, at least a part of its role has been as a means of editorial commentary, a light shone on crisis, crime, or social ills. The great urban reformer Jacob Riis used it to chronicle the horrific gulf between poor and rich in the legendary photo essay How The Other Half Lives. Arthur Rothstein, Dorothea Lange and Lewis Hine, among many others, turned their cameras on the desperate need and changing landscape of America’s Great Depression. And now is the time for another great awakening in photography. It’s time to show where our cities need to go next.

Politics aside, the rotting state of our urban infrastructures is an emergency crying out for the visual testimony that photographers brought so eloquently to bear on poverty and war in ages past. The magnifying glass needs to be turned on the neglect that is rapidly turning America’s urban glory into rust and ruin. And no one can tell this story better than the camera.

We can fine-tune all the arguments about how to act, what to fund, and how to proceed. That’s all open to interpretation and policy. But the camera reveals the truths that are beyond abstraction and opinion. The underpinnings of one of the world’s great nations are rapidly dissolving into exposed rebar and pie-crust pavement. If part of photography’s mission is to report the news, then the decline of our infrastructure is one of the most neglected stories in the world’s visual portfolio. Photographers can entice the mind into action, and have done so for nearly two centuries. They have peeled back the protective cover of politeness to reveal mankind at its worst, and things have changed because of it. Agencies have been formed. Action has been accelerated. Lives have been changed. Jobs have been created.

It didn’t used to be an “extra credit” question on the exam of life just to maintain what amazing things we have. Photographers are citizens, and citizens move the world. Not political parties. Not kings or emperors. History is created from the ground up, and the camera is one of the most potent storytelling tools used in shaping that history. The story of why our world is being allowed to disintegrate is one well worth telling. Capturing it in our boxes just might be a way to shake up the conversation.

Again.

THE GEOMETRY OF VIEW

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE BEST WAYS TO APPREHEND THE OVERALL DESIGN OF A SPACE, be it a midtown skyscraper or a suburban cathedral, is to see it the way the designer originally envisioned it; as a logical arrangement of spaces and shapes. Sometimes, viewing the layout of floors, lobbies, or courtyards from the top-down, or “bird’s-eye” view of the original design sketches is especially helpful, since it takes our eye far enough away from a thing to appreciate its overall conception. It’s also not a bad thing for a photographer to do when trying to capture common spaces in a new way. Move your camera, change your view, change the outcome of your images.

The overarching vision for a place can be lost at ground, or “worker bee” level, in the horizontal plane along which we walk and arrange our viewpoint. Processing our understanding of architecture laterally can only take us so far, but it almost seems too simple to suggest that we shift that processing just by changing where we stand. And yet you will invariably learn something compositionally different just by forcing yourself to visualize your subjects from another vantage point.

I’m not suggesting that the only way to shake up your way of seeing big things is to climb to the top floor and look down. Or descend to the basement and look up, for that matter. Sometimes it just means shooting a familiar thing from a fresh angle that effectively renders it unfamiliar, and therefore reinvents it to your eye. It can happen with a different lens, a change in the weather, a different time of day. The important thing is that we always ask ourselves, almost as a reflex, whether we have explored every conceivable way to interpret a given space.

Each fresh view of something re-orders its geometry in some way, and we have to resist the temptation to make much the same photographs of a thing that everyone else with a camera has always done. We’re not in the postcard business, so we’re not supposed to be in the business of assuring people with safe depictions of things, either. Photography is about developing a vision, then ripping it up, taping it back together out-of-order, shredding that, and assembling it anew, again and again. In a visual medium, any other approach will just make us lazy and make our art flat and dull.

SOMETIMES THE MAGIC WORKS…

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE DIGITAL ERA IN PHOTOGRAPHY HAS SMASHED DOWN THE DOORS TO WHAT WAS ONCE A FAIRLY EXCLUSIVE CLUBHOUSE, a select brotherhood (or sisterhood) of wizards who held all the secrets of their special science. The wizzes got great results and created “art. The rest of us slobs just took snapshots.

Today, the emphasis in photographic method has shifted from understand, study and do, to do, understand and, maybe study. We are now a nation of confident what-the-hellers. Try it, and if it don’t work, try something else. In some ways, this is a shift away from intellect and toward instinct. We are all either a little less technically aware of why the magic works, or completely indifferent to the underlying processes at work. You can all huddle together and decide whether this is a good thing.

Which, by way of introduction, is a way of saying that sometimes you do something that flies in the face of science or sense and it still works out. To illustrate, let us consider the humble polarizing filter, which, for me, is more important than many of the lenses I attach it to. It richens colors, cuts reflections, and eliminates the washed-out look of shots taken in intense daylight sun, as well as taming the squinty haze caused by smog. Or, if you want the Cliff’s Notes version, it makes skies blue again.

Now there is a “proper” way to get top results with a polarizer. Make an “L” with your index finger and thumb, finger pointing straight up. UP in this example is the position of the sun overhead, and your thumb, about 90 degrees opposed to your finger, roughly represents your camera’s lens. The closer to 90 degrees that “L” is, the more effective the filter will be in reducing glare and boosting color. Experts will tell you that using a polarizer any other way will deliver either small or no results. That’s it. Gospel truth, science over superstition, settled argument.

That’s why I can’t explain the two pictures in this post, taken just after sunrise, both with and without the filter. In the first, seen at left, Los Angeles’ morning haze is severe, robbing the rooftop image of contrast and impact. In the second, shown above, the sky is blue, the colors are intense and shadows are really, well, shadows. But consider: not only is the sun too low in the sky for the filter’s accepted math to work, I am standing inside a hotel room, and yet the filter still does its duty, and all is right with the world. If I had followed and obeyed package directions, this shot should not have worked. That means if I were to pre-empt myself, defaulting to what is scientific and “provable”, and ignoring my instinct, I would not even have tried this image. The takeaway: perhaps I need to preserve just enough of the ignorant noobie I once was, and let him take the wheel sometimes, even if the grown-up in me says it can’t be done.

The yin and yang wrestling match between intellect and instinct is essential to photography. Too much science and you get sterility. Too much gut and you get garbage. As usual,the correct answer is provided by what you are visualizing. Here. Now. This moment.

ANATOMY OF A BOTCH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE SHOULD BE A MIRROR-IMAGE, “NEGATIVE” COOKBOOK FOR EVERY REGULAR ONE PUBLISHED, since there are recipes for inedible failures, just as surely as there are ones for gustatory delights. It might be genuinely instructive to read an article called How To Turn A Would-Be Apple Pie Into A Shapeless Heap Of Glop or You, Too Can Make Barbecue Ribs Look Like The Aftermath Of A Cremation. So too, in photography, I believe I could easily pen an essay called How To Take Pictures That Make It Seem That You Never Touched A Camera Before.

In fact…..

In recent days, I’ve been giving myself an extra welt or two with the flagellation belt in horrified reaction to a shoot that I just flat-out blew.It was a walk through a classic hotel lobby, a real “someday” destination for myself that I finally got to visit and wanted eagerly to photograph. Thing is, none of that desire made it into the frames. Nor did any sense of drama, art, composition, or the basics of even seeing. It’s rare that you crank off as many shots as I did on a subject and wind up with a big steaming pile of nothing to show for it, but in this case, I seem to have been all thumbs, including ten extra ones where my toes should be.

So, if I were to write a negative recipe for a shoot, it would certainly contain a few vital tips:

First, make sure you know nothing about the subject you’re shooting. I mean, why would you waste your valuable time learning about the layout or history of a place when you can just aimlessly wander around and whale away? Maybe you’ll get lucky. Yeah, that’s what makes great photographs, luck.

Enjoy the delightful surprise of discovering that there is less light inside your location than inside the fourth basement of a coal mine. Feel free to lean upon your camera to supply what you don’t have, i.e., a tripod or a brain. Crank up the ISO and make sure that you get something on the sensor, even if it’s goo and grit. And shoot near any windows you have, since blowouts look so artsy contrasted with pitch blackness.

Resist the urge to have any plan or blueprint for your shooting. Hey, you’re an artist. The brilliance will just flow as you sweep your camera around. Be spontaneous. Or clueless. Or maybe you can’t tell the difference.

Stir vigorously and for an insane length of time with a photo processing program, trying to manipulate your way to a useful image. You won’t get there, but life is a journey, right? Even when you’re hopelessly lost in a deep dark forest.

************************

You could say that I’m being too Catholic about this, and I would counter that I’m not being Catholic enough.

Until I do penance.

Gotta go back someday and do it right.

And make something that really cooks.

THE JOY OF BEING UNIMPORTANT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE AT LEAST TWO WOMEN IN MY LIFE WHO WORRY if I am sufficiently entertained whenever I am borne along on their ventures into various holy lands of retail. Am I waiting too long? Am I bored at being brought along? Would I like to go somewhere else and rejoin them later at an appointed time and place?

Answers: No to questions 1, 2 and 3…so long as I have my hands on a camera.

I can’t tell you how many forays into shoe emporiums, peeks into vintage stores and rambles through ready-to-wear shops have provided me with photographic material, mainly because no one would miss me if I were to disappear for a bit, or for several days. And, as I catalogue some of the best pickings I’ve plucked from these random wanderings, I find that many of them were made possible by the simple question, “do you mind amusing yourself while I try this on?” Ah, to have no authority or mission! To let everything pale in importance when compared to the eager search for pictures! To be of so little importance that you are let off the leash.

The above image happened because I was walking with my wife on the lower east side of Manhattan but merely as physical accompaniment. She was looking for an address. I was looking for, well, anything, including this young man taking his cig break several stories above the sidewalk. He was nicely positioned between two periods of architecture and centered in the urban zigzag of a fire escape. Had I been on an errand of my own, chances are I would have passed him by. As I was very busy doing nothing at all, I saw him.

Of course, there will be times when gadding about is only gadding about, when you can’t bring one scintilla of wisdom to a scene, when the light miracles don’t reveal themselves. Those are the times when you wish you had pursued that great career as a paper boy, been promoted to head busboy, or ascended to the lofty office of assistant deacon. I’m telling you: shake off that doubt, and celebrate the glorious blessing of being left alone…to imagine, to dream, to leave the nest, to fail, to reach, to be.

Photography is about breaking off with the familiar, with the easy. It’s also having the luck to break off from the pack.

ON THE STRAIGHT AND NARROW

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE NARROW STREETS OF LOWER MANHATTAN WERE NEVER DESIGNED TO ACCOMMODATE the claustrophobic jam of commerce, foot traffic and skyscrapers that have characterized the neighborhood since the early 20th century. I should back that up and acknowledge that, for some locals, the streets of lower Manhattan were never designed,period. New York’s growth has always come in rangy spurts and jolts, much like a gangly adolescent that shoots upward and outward overnight without any apparent plan, and yet, those unruly explosions are also what delight the photographer’s eye and make the city an inexhaustible laboratory for technique.

Shooting down the slits that pass for side streets and alleys in lower Manhattan is enough to make even the most seasoned native feel like he or she is being shut up in a tomb, but I am drawn to going even further, and over-emphasizing the extreme dimensions peculiar to the area. That, for me, means shooting with as wide a lens as I have handy, distortion be damned. Actually, it’s distortion be welcomed, since I think that the horizontal lines of the buildings create a much more dramatic lead-in for the eye as they race far away from the foreground. And since ultra-wide magnify front-to-back distances, the bigness and closeness of the city is jacked into a real exaggeration, but one that serves my purpose.

It helps to crouch down and tilt up when composing the shot, and to make sure that you don’t crop passersby out of the shot, since they will add to the drama even more as indications of scale. I have certainly gone too far more than once and rendered rectangular buildings into futuristic trapezoids, but the aim of each image will dictate what you’re going for. Also, in many of these shots, I decide, after much dithering, to choose monochrome over color, but I always shoot the originals in color, since they respond better to re-contrasting once they’re desaturated.

The magic about Manhattan is that no camera can ever tame her or show all her beauty and/or ugliness. It’s somthing of a fool’s errand to try to take the picture of NYC. Better to take a picture you like and add it to the ongoing story.

THE AGE OF ELEGANCE

If only we’d stop trying to be happy, we could have a pretty good time.——Edith Wharton

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LONG BEFORE HER NOVELS THE AGE OF INNOCENCE, ETHAN FROME, AND THE HOUSE OF MIRTH made her the most successful writer in America, Edith Wharton (1862-1937) was the nation’s first style consultant, a Victorian Martha Stewart if you will. Her 1897 book, The Decoration Of Houses, was more than a few dainty gardening and housekeeping tips; it was a philosophy for living within space, a kind of bible for combining architecture and aesthetics. Her ideas survive in tangible form today, midst the leafy hills of Lenox Massachusetts, in the Berkshire estate her family knew as “The Mount”.

Wharton only occupied the house from 1902 to 1911, but in that time established it as an elegant salon for guests that included Henry James and other literary luminaries. Although based on several classical styles, the house is a subtle and sleek counter to the cluttered bric-a-brac and scrolled busyness of European design. Even today, the house seems oddly modern, lighter somehow than many of the robber-baron mansions of the period. Many of its original furnishings went with Wharton when she moved to Europe, and have been replicated by restorers, often beautifully. But is in the essential framing and fixtures of the old house that the writer-artist speaks, and that is what led me to do something fairly rare for me, a photo essay, seen at the top of this page in the menu tab Edith Wharton At The Mount.

The images on this special page don’t feature modern signage, tour groups, or contemporary conveniences, as I attempt to present just the basic core of the estate, minus the unavoidable concessions to time. The house features, at present, an appealing terrace cafe, a sunlit gift store, and a restored main kitchen, as part of the conversion of the mansion into a working museum. I made no images of those updates, since they cannot conjure 1902 anymore than a Mazerati can capture the feel of a Stutz-Bearcat. The pictures are made with available light only, and have not been manipulated in any way, with the exception of the final shot of the home as seen from its rear gardens, which is a three-exposure HDR, my attempt to rescue the detail of the grounds on a heavily overcast day.

Take a moment to click the page and enter, if only for a moment, Edith Wharton’s age of elegance.