THE FLOATING 50

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU CANNOT BECOME A GREAT PHOTOGRAPHER WITHOUT BEING YOUR OWN BEST EDITOR, no matter how brilliant or instinctual your shooter’s eye may be. Art is both addition and subtraction, and the image frame is about both inclusion and exclusion. You get your viewers’ attention by knowing what to show. You hold that attention, and burn your images into their minds, by learning what to pare away.

I’ve written several variations on this theme, so the best way to restate it is in the voice of the truly visionary godfather of street photography, Henri Cartier-Bresson. Ironically, this master of in-camera composition (he is reputed never to have cropped a single shot after it was taken) was nonetheless remarkably aware of what most of us must do to improve an image through post-editing:

This recognition, in real life, of a rhythm of surfaces, lines, and values is for me the essence of photography; composition should be a constant of preoccupation, being a simultaneous coalition – an organic coordination of visual elements. We must avoid snapping away, shooting quickly and without thought, overloading ourselves with unnecessary images that clutter our memory and diminish the clarity of the whole.

Insert whatever is French for “Amen” here.

I often find that up to 50% of some of my original shots can later be excised without doing any harm to the core of the photograph, and that, in many cases, actually improving them. Does that mean that my original concept was wrong? Not so much, although there are times when that’s absolutely true. The daunting thing is that the 50% floats around. Sometimes you need to cut the fat in the edges: other times the dead center of the shot is flabby. Sometimes the 50 is aggregate, with 25% trimmed from two different areas of the overall composition.

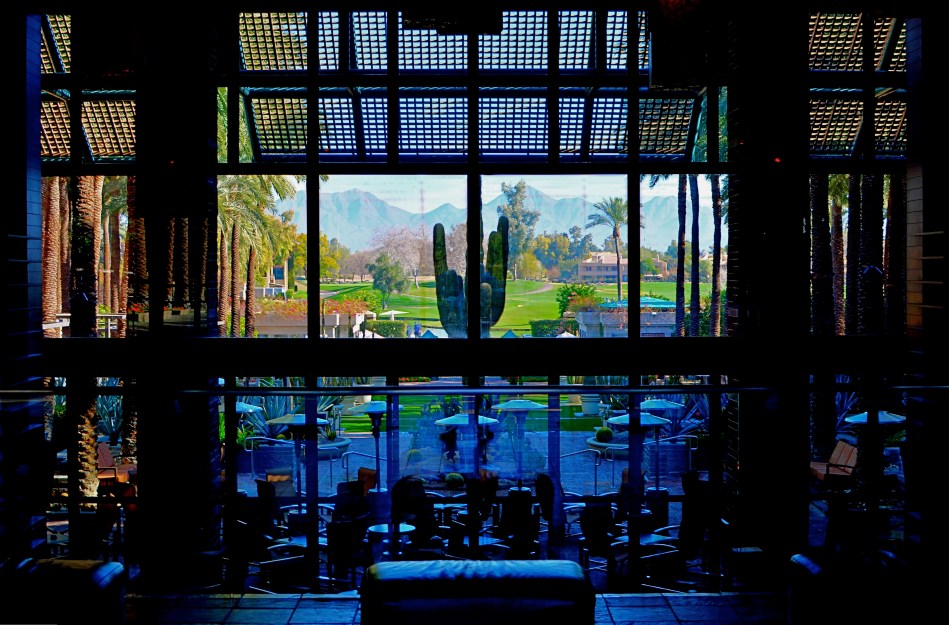

On occasion, as with the above picture (see the original off to the left), the entire bottom half of the shot drags down the top. In the cropped shot, the long lateral line between indoors and outdoors is much more unbroken, making for a more “readable” shot from left to right. The disappearance of the dark furniture at the bottom of the master shot creates no problems, and actually solves a few. Do a disciplined search of the nobler near-misses in your own work and see how many floating 50’s you discover. Freeing your shots of the things that “clutter our memory and diminish the clarity of the whole” is humbling, but it’s also a revelation.

NAIL YOUR FOOT TO THE FLOOR

I shot this on a day when I was forcing myself to master a manual f/2.8 lens wide open, and thus shoot all day in only that aperture. That made depth-of-field tricky.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY PLACES YOU IN PLENTY OF SITUATIONS WHERE YOU ARE, TO SOME DEGREE, OUT OF CONTROL. From light conditions to the technical limits of your gear to erratic weather, we have all experienced that sinking feeling that accompanies the realization that, to a great extent, we are not in the driver’s seat. Gotta wait til the sun’s up. Gotta wait for the flash to recycle. Gotta cool my heels til these people get out of the frame. Gotta getta bigger bottle of Tums.

So why, given the frequent cases in which we naturally run off the rails, would I recommend that you deliberately hobble yourself, in effect putting barriers in your own way when shooting images? Because, quite simply, failure is a better teacher than success, and you never forget the lessons gained by having to work around a disadvantage. Not only am I encouraging you to flirt with failure, I’m suggesting that there are even perfect days on which to do it…that is, the many days when there is “nothing to shoot”.

It’s really practical, when you think of it. Go out shooting on a day when the subject matter is boring, a day on which you could hardly be expected to bring back a great picture. Then nail your foot to the floor in some way, and bring back a great picture anyway. Pick an aperture and shoot everything with it, without fail (as in the picture at left). Select a shutter speed and make it work for you in every kind of light. Act as if you only have one lens and make every shot for a day with that one hunk of glass. Confine your snaps to the use of a feature or effect you don’t use or understand. Compose every shot from the same distance. The exercise matters less than the discipline. Don’t give yourself a break. Don’t cheat.

In short, shoot stuff you hate and make pictures that don’t matter, except in one respect: you utilized all of your ingenuity in making them. This redeems days that would otherwise be lost, since your shoot-or-die practice sessions make you readier when the shots really do count.

It’s not a lot different from when you were a newbie a primitive camera on which all the settings were fixed and you had zero input beyond framing and clicking. With “doesn’t matter” shooting, you’re just providing the strictures yourself, and maneuvering around all the shortcomings you’ve created. You are, in fact, involving yourself deeper in the creative process. And that’s great. Because someday there will be something to shoot, and when there is, a greater number of your blown photos are already behind you.

IF HUE GO AWAY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT SEEMS UNGRACIOUS FOR A PHOTOGRAPHER TO COMPLAIN ABOUT AN OVER-ABUNDANCE OF LIGHT, since that’s basically the currency we trade in. More typically we gripe about not being able to bring enough of the stuff into a shot. I mean, the entire history of the medium is one big let-there-be-more-light prayer. But that’s not to say that light can’t create annoyance when you’re in a place where there is glorious, radiant illumination of….acres of nothing.

I’m not talking about sunlight on endless expanses of starched plain. I refer here to subject matter that is so uninteresting that, even though a bumptious bounty of light is drenching everything in sight, there is nothing to make a photograph of. Nothing that compels, inspires, jars or even registers. I recently made my annual return to a festival that, due to my frequent farming of it over the years, has now bottomed out visually. There is nothing left to say about it, although all that “nothing” is stunningly lit at this time of year.

In fact, it’s only by shooting just abstracted shapes, shades and rays, rather than recognizable subjects, that I was able to create any composition even worth staying awake for, and then only by using extremely sharp contrast and eliminating color completely. To me, the only thing more pointless than lousy subject matter is beautiful looking lousy subject matter, saturated in golden hues, but signifying nothing. Kinda the George Hamilton of photos.

So the plan became, simply, to turn my back on the bright balloons, food booths, passing parade of people and spring scenery that, in earlier years, I would have been happy to capture, and instead render arrangements without any narrative meaning, just whatever impact could be seen using light as nearly the lone element. In the above picture, I did relent in keeping the silhouetted couple in the final picture, so that it’s not as “cold” as originally conceived, but otherwise it’s a pretty stark image. Photography without light is impossible, but we also have to refuse to take light “as is” from time to time, to do our best to orchestrate it, much as we would vary shadings with pencil or crayon. We know that the camera loves light, but it’s still our job to tell it where, and how, to look.

(DON’T) WATCH THIS SPACE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CALL IT “EYE-HERDING”, if you will, the art of channeling the viewer’s attention to specific parts of the photographic frame. It’s the first thing we learn about composition, and we address it with a variety of techniques, from depth-of-field to color manipulation to one of my favorites, the prioritizing of light. Light values in any image do have a hierarchy, from loud to soft, prominent to subordinate. Very few photos with uniform tone across the frame achieve maximum impact. You need to orchestrate and capitalize on contrast, telling your viewers, in effect, don’t watch this space. Watch this other space instead.

In many cases, the best natural ebb and flow of light will be there already, in which case you simply go click, thank the photo gods, and head home for a cold one. In fact, it may be that “ready to eat” quality that lured you to stop and shoot the thing in the first place. In many other cases, you must take the light values you have and make the case for your picture by tweaking them about a bit.

I have written before of the Hollywood fakery known as “day for night”, in which cinematographers played around with either exposure or processing on shots made in daylight to simulate night…a budgetary shortcut which is still used today. It can be done fairly easily with still images as well with a variety of approaches, and sometimes it can help you accentuate a light value that adds better balance to your shots.

The image at the top of this page was made in late afternoon, with pretty full sun hitting nearly everything in the frame. There was some slightly darker tone to the walls in the street, but nothing as deep as you see here. Thing is, I wanted a sunset “feel” without actually waiting around for sunset, so I deepened the overall color and simulated a lower exposure. As a result, the sky, cliffs and dogwood trees at the far end of the shot got an extra richness, and the shop walls receded into deeper values, thus calling extra attention to the “opening” at the horizon line. The shot also benefits from a strong front-to-back diagonal leading line. I liked the original shot, but with just a small change, I was asking the viewer to look here a little more effectively.

Light is a compositional element no less important than what it illuminates. Change light and you change where people’s eyes enter the picture, as well as where they eventually land.

SHADOWS AS STAGERS

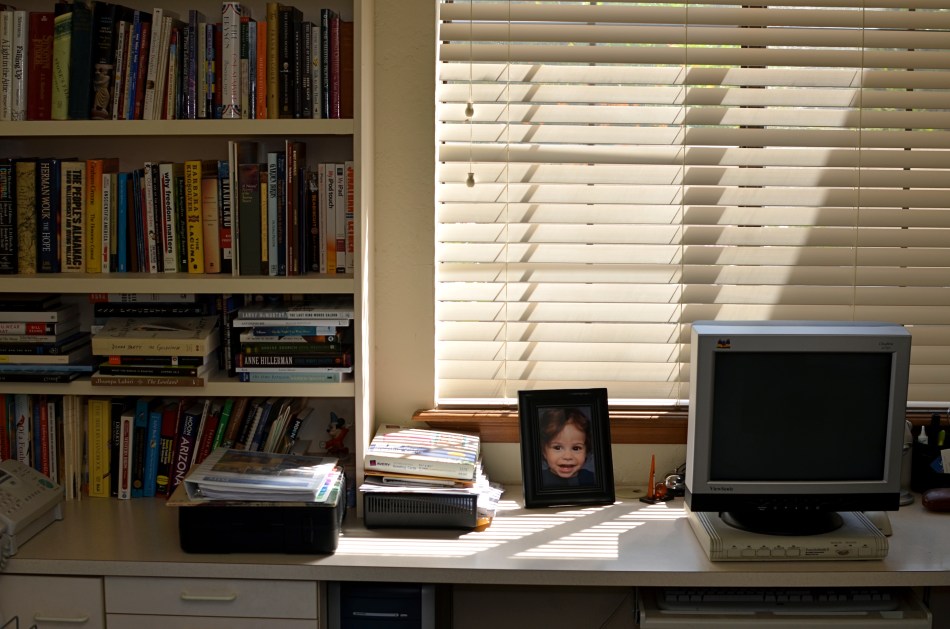

The idea of this image is to highlight what lies beyond the window framing, not the objects in front of it. Lighting should serve that end.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THOSE WHO ADHERE TO THE CLASSIC “RULE OF THIRDS” system of composition often suggest that you imagine your frame with a nine-space grid super-imposed over it, the better to help you place your subject in the greatest place of visual interest. This place is usually at the intersection of several of these grid lines, and, whether or not you strictly adhere to the “thirds” system, it’s useful to compose your shots purposefully, and the grid does give you a kind of subliminal habit of doing just that.

Sometimes, however, I find that the invisible grid can be rendered briefly visible to become a real part of your composition. That is to say, framing through silhouetted patterns can add a little dimension to an otherwise flat image. Leaving some foreground elements deliberately underlit is kind of a double win, in that it eliminates detail that might read as clutter, and helps hem in the parts of the background items you want to most highlight.

These days, with HDR and other facile post-production fixes multiplying like rabbits on Viagra, the trend has been to recover as much detail from darker elements as possible. However, this effect of everything being magically “lit” at one even level can be a little jarring since it clearly runs counter to the way we truly see. It’s great for novel or fantasy shots, but the good old-fashioned silhouette is the most elemental way to add the perception of depth to a scene as well as steering attention wherever you need it. Shadows can set the stage for certain images in a dramatic fashion.

Cheap. Fast. Easy. Repeat.

HAPPY OLD YEAR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

The White Rabbit put on his spectacles. ‘Where shall I begin, please your Majesty?’ he asked. ‘Begin at the beginning,’ the King said gravely, ‘and go on till you come to the end: then stop.’

IN A SIMPLER WORLD, THE KING OF HEARTS, quoted above in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, would be perfectly correct. All things being equal, the beginning would be the best place to begin. But, in photography, as in all of life, we are always coming upon a series of beginnings. Learning an art is like making a lap in Monopoly. Just when we think we are approaching our destination, we pass “Go” again, and find that one man’s finish line is another man’s starting gate. Photography is all about re-defining where we are and where we need to be. We always begin, and we never finish.

As 2014 comes to an intersection (I can’t really say ‘a close’ after all that, can I?), it’s normal to review what might be either constant, or changed, about one’s approach to making pictures. That, after all, is the stated aim of this blog, making The Normal Eye more about journey than destination. And so, all I can do in reviewing the last twelve months of opportunities or accidents is to try to identify the areas of photography that most define me at this particular juncture, and to reflect on the work that best represents those areas. This is not to say I’ve gained mastery, but rather that I’m gaining on it. If my legs hold out, I may get there yet. But don’t count on it.

The number twelve has become, then, the structure for the blog page we launch today, called (how does he think of these things?) 12 for 14. You’ll notice it as the newest gallery tab at the top of the screen. There is nothing magical about the number by itself, but I think forcing myself to edit, then edit again, until the thousands of images taken this year are winnowed down to some kind of essence is a useful, if ego-bruising, exercise. I just wanted to have one picture for each facet of photography that I find essentially important, at least in my own work, so twelve it is.

Light painting, landscape, HDR, mobile, natural light, mixed focus, portraiture, abstract composition, all these and others show up as repeating motifs in what I love in others’ images, and what I seek in my own. They are products of both random opportunity and obsessive design, divine accident and carefully executed planning. Some are narrative, others are “absolute” in that they have no formalized storytelling function. In other words, they are a year in the life of just another person who hopes to harness light, perfect his vision, and occasionally snag something magical.

So here we are at the finish line, er, the starting gate, or….well, on to the next picture. Happy New Year.

FIVE-DECKER SANDWICH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MY PHOTOGRAPHY IS OCCASIONALLY AKIN TO MY GRANDMOTHER’S COOKING METHOD, which produced culinary miracles without a trace of written recipes or cookbooks. Her approach was completely additive; she merely kept throwing things into the pot until it looked “about right”. I was aware of the difference, in her hands, between portions that were labeled “smidges”, “tastes”, “pinches” and even “tads” (as in, “this is a tad too bitter. Give me the salt.) I never questioned her results: I merely scarfed them down and eagerly asked for seconds.

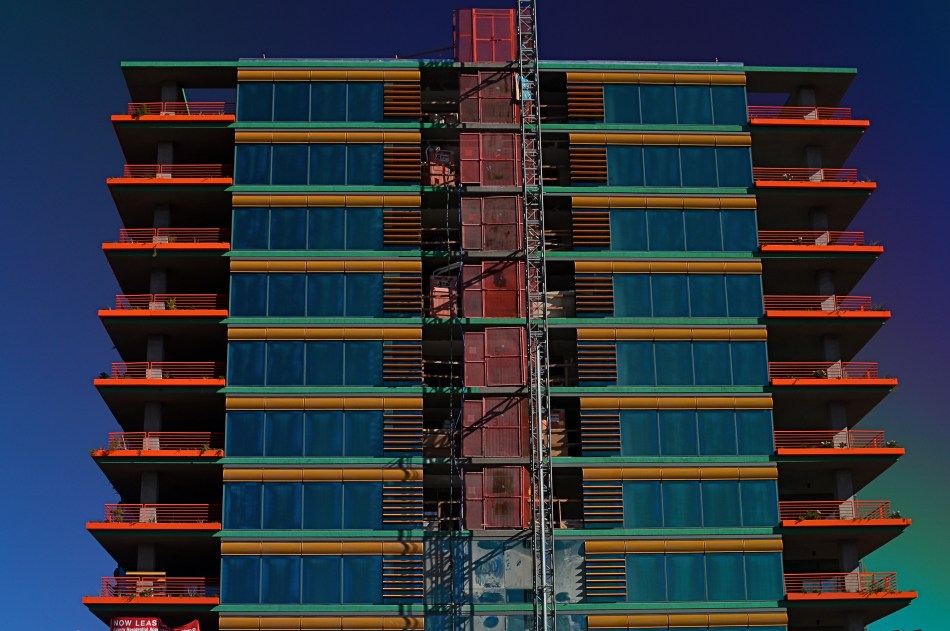

Picture making can also be a matter of adding enough pinches and tads to create just the right mix of factors for the image you need. It’s frequently as instinctual a process as Gram’s, but sometimes you have to analyze what worked by thinking the shot backwards after the fact. In the case of the above image, what you see, although it was shot very quickly, is actually the convergence of several different ingredients, the combination of which would be all wrong for some photos, but which actually served this subject fairly well.

The five-decker sandwich of factors in the shot begins with the building, which is quite intense in color all by itself, yet not quite contrasty enough to suit me in this specific instance. So let’s see all the hoops the camera had to jump through to get this particular image:

First, it was taken during the so-called “golden hour”, just before sunset, in late fall in Arizona. That guarantees at least one boost of the building’s native intensity. The next factor is the camera’s own color settings, which are set to “vibrant.” Level three comes from a polarizing filter, which is juicing the sky from its hazy southwestern “normal” to a deep blue. For the fourth element, I am also adding a second filtering component by shooting through a heavily tinted car window (there’s no other kind in Arizona), which presents here as the gradation of sky from blue at the top of the frame to a near aqua near the bottom. And finally, I am way under-exposing the shot at 1/320, deepening the colors yet one more time.

The fun of this is that it all happens ahead of the click, and keeps your fingers off the Photoshop trigger. Grandma may not have spent any more time laboring over a photo than a quick snap of a box Brownie, but she knew how to take stew meat and morph it into filet. And, as with the making of a picture, you just keep adding stuff until the mixture in the pot looks “about right.”

FADE TO (ALMOST) BLACK

Sometimes a change in the technical approach to a shot is the only way to freshen an old subject. 1/40 sec., f/1.8, ISO 250, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I KNOW MANY PHOTOGRAPHERS WHO SUBJECT THEMSELVES TO THE DELICIOUS TORTURE, known to authors everywhere,as “publish or perish”, or, in visual terms, the tyranny of shooting something every single day of their lives. There are lots of theories afloat as to whether this artificially imposed discipline speeds one’s development, or somehow pumps their imagination into the bulky heft of an overworked bicep. You must decide, o seekers of truth, what merit any of this has. I myself have tried to maintain this kind of terrifying homework assignment, and during some periods I actually manage it, for a while at least. But there are roadblocks, and one of the chief barriers to doing shot-a-day photography is subject matter, or rather the lack of it.

Let’s face it: even if you live one canyon away from the most breathtaking view on earth or walk the streets of the mightiest metropolis, you will occasionally look upon your immediate environs as a bad rerun of Gilligan’s Island, something you just can’t bear to look at without having a wastebasket handy. Familiarity breeds contempt for some subjects that you’ve visited and re-visited, and so, for me, the only way to re-mix old material is to re-imagine my technical approach to it. This is still a poor substitute for a truly fresh challenge, but it can teach you a lot about interpretation, which has transformed more than a few mundane subjects for me over a lifetime of shuttering (and shuddering).

As an example, a corner of my living room has been one of the most trampled-over crime scenes of my photographic life. The louvered shades which flank my piano can create, over the course of a day, almost any kind of light, allowing me to use the space for quick table-top macros, abstract arrangements of shadows, or still lifes of furnishings. And yet, on rainy /boring days, I still turn to this corner of the house to try something new with the admittedly over-worked material. Lately I have under-exposed compositions in black and white, coming as near a total blackout as I can to try to reduce any objects to fundamental arrangements of light and shadow. In fact, damn near the entire frame is shadow, something which works better in monochrome. Color simply prettifies things too much, inviting the wrong kind of distracted eye wandering in areas of the shot that I don’t think of as essential.

I crank the aperture wide open (or nearly) to keep a narrow depth of field, which renders most of the image pretty soft. I pinch down the window light until there is almost no illumination on anything, and allow the ISO to float around at least 250. I get a filmic, grainy, gauzy look which is really just shapes and light. It’s very minimalistic, but it allows me to milk something fresh out of objects that I’ve really over-photographed. If you believe that context is everything, then taking a new technical approach to an old subject can, in fact, create new context. Fading almost to black is one thing to try when you’re stuck in the house on a rainy day.

Especially if there’s nothing on TV except Gilligan.

THE BOY IN THE BALL CAP

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MORE SHOTS, MORE CHOICES: Photography really is as simple as that. The point has been hammered home by expert and amateur alike since before we could say “Kodak moment”: over-shooting, snapping more coverage from more vantage points, results in a wider ranger of results, which, editorially, can lead to finding that one bit of micro-mood, that miraculous mixture of factors that really does nail the assignment. Editors traditionally know this, and send staffers out to shoot 120 exposures to get four that are worthy of publication. It really, ofttimes, is a numbers game.

For those of us down here in the foot soldier ranks, it’s rare to see instances of creative over-shoot. We step up to the mountain or monument, and wham, bam, there’s your picture. We tend to shoot visual souvenirs: see, I was there, too. Fortunately, one of the times we do shoot dozens upon dozens of frames is in the chronicling of our families, especially the day-to-day development of our children. And that’s vital, since, unlike the unchanging national monument we record on holiday, a child’s face, especially in its earlier years, is a very dynamic subject, revealing vastly different features literally from frame to frame. As a result, we are left with a greater selection of editing choices after those faces dissolve into other faces, after which they are gone in a thrilling and heartbreaking way.

One humbling thing about shooting kids is that, after they have been around a while, you realize that you might have caught something essential, months or years ago, during an event at which you just felt like you were reacting, racing to catch your quarry, get him/her in focus, etc. A feeling of always trying to catch up. It’s one of the only times in our own lives that we shoot like paparazzi. This might be something, better get it. I’ll sort it out later. The process is so frenetic that some images may only reveal their gold several miles down the road.

Not the sharpest image I ever shot, but look at that face. Slow shutter to compensate for the dim light. 1/40 sec., f/3.2, ISO 200, 35mm.

My grandson is now entering kindergarten. He’s reading. He’s a compact miniature of his eventual, total self. And, in recently riffing through images of him from early five years ago (and yes, I was sniffling), I found an image where he literally previews the person I now know him to be. This image was always one of my favorite pictures of him, but it is more so now. In it, I see his studious, serious nature, and his intense focus, along with his divine vulnerability and innocence. Technically, the shot is far from perfect, as I was both racing around to catch him during one of his impulse-driven adventures and trying to master a very new lens. As a result, his face is a little soft here, but I don’t know if that’s so bad, now that I view it with new eyes. The light in the room was itself pretty anemic, leaking through a window from a dim day, and running wide open on a 50mm f/1.8 lens at a slow 1/40 was the only way I was going to get anything without flash, so I risked misreading the shallow depth of field, which I kinda did. However, I’ll take this face over the other shots I took that day. Whatever I was lacking as a photographer, Henry more than compensated for as a subject.

Final box score: the boy in the ball cap hit it out of the park.

Thanks, Hank.

RAMPING UP

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN THE IMAGINARY PHOTOGRAPHY BOOKSHELF OF MY MIND THERE ARE HUNDREDS OF VOLUMES that speak of nothing else except the exquisite light of early morning, the so-called “golden hour” in which a certain rich warmth bathes all. You’ve read endless articles and posts on this as well, so nothing I can cite about the science or aesthetic aspects of it can add much. However, I think that there is a secondary benefit to shooting early in the day, and it speaks to human rhythm, a factor which creates opportunities for imaging every bit as vital as the quality of available light.

Cities and communities don’t jolt awake in one surge: they gently creep into life, with streets gradually taking on the staging that will define that day. The first signs could be the winking on of lights, or the slow, quiet shuffle of the first shift of cleaners, washers, trimmers and delivery workers. First light brings the photographer a special relationship with the world, as he/she has a very private audience with all the gears that will soon whirr and buzz into the overall noise of the day. You are witness to a different heartbeat of life, and the quieter pace informs your shooting choices, seeping into you in small increments like a light morning dew. You are almost literally forced to move slower, to think more deliberately, and that state always makes for better picture making.

Some atmospheres, like libraries or churches, retain this feel throughout the entire day, imposing a mood of silence (or at least contemplation) that is also conducive to a better thought process for photography, but in most settings, as the day wears on, the magic wears off. Early day is a distinctly different day from the one you’ll experience after 9am. It isn’t merely about light, and, once you learn to re-tune your inner radio for it, you can find yourself going back for more.

This is no mere poetic dreaminess. The more nuances you experience as a living, breathing human, the more you have to pour into your photography. Live fuller and you’ll shoot better. That’s why learning about technical things is no guarantee that you’ll ever do anything with a camera beyond a certain clinical “okay-ness”. On the other hand, we see dreamers who are a solid C+ on the tech stuff deliver A++ images because their soul is part of the workflow.

THE LAST PIECE OF THE PUZZLE

By “available light”, I mean any $%#@ light that’s available. —-Joe McNally, world-renowned master photographer, author of The Moment It Clicks

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE EASIEST THINGS ABOUT ANALYZING THOSE OF OUR SHOTS THAT FAIL is that there is usually a single, crucial element that was missing in the final effort….one tiny little hobnail, without which the entire image simply couldn’t hold together. In a portrait, it could be a wayward turn of face or hint of a smile; in a landscape it could be one element too many, moving the picture from “charming” to “busy”. The secret to greater success, then, must lie in pre-visualizing a photograph to as great a degree as possible, in knowing in advance how many puzzle pieces must click into place to make the result work.

I recently attended an outdoor dance recital, during which I knew photography would be prohibited. I had just resigned myself to spend the night as a mere spectator, and was settling onto my lawn seat when some pre-show stretching exercises by the dancing company presented me with an opportunity. The available natural light in the sky had been wonderfully golden just minutes before, but, by the time the troupe took the stage and started into their poses and positions, it had grown pretty anemic. And then a stage hand gave me back that missing “puzzle piece”.

Positions, Please, 2014. One light source at dusk, courtesy of a light tech rehearsing with the rehearsers.

Climbing the gridwork at the right side of the stage, the techie was turning various lights on and off, trying them with gels, arcing them this way or that, devising various ways to illuminate the dancers as their director ran them through their paces. I decided to get off my blanket and hike down to the back edge of the stage, then wait for “my light” to come around in the rotation. Eventually, the stage hand turned on a combination that nearly replicated the golden light that I no longer was getting from the sky. It was single-point light, wrapping around the bodies of some dancers, making a few of them glow brilliantly, and leaving some other swaddled in shadow, reducing them to near-silhouettes.

For a moment, I had everything I needed, more than would be available for the entire rest of the evening. Now the physical elegance of the ballet cast was matched by the temporary drama of the faux-sunset coming from stage left. I moved in as closely as I could and started clicking away. I was shooting at something of an upward slant, so a little sky cropping was needed in the final shots, but, for about thirty seconds, someone else had given me the perfect key light, the missing puzzle piece. If I could find that stage hand, I’d buy her a few rounds. The win really couldn’t have happened without her.

REVENGE OF THE ZOO

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PURISTS IN THE ANIMAL PHOTOGRAPHY GAME OFTEN DISPARAGE IMAGES OF BEASTIES SHOT AT ZOOS, citing that they are taken under “controlled conditions”, and therefore somewhat less authentic than those taken while you are hip-deep in ooze, consumed by insects, or scratching any number of unscratchable itches. Editors won’t even consider publishing pics snapped at the local livestock lockup, as if the animals depicted in these photos somehow surrendered their union cards and are crossing a picket line to work as furry scabs .

This is all rubbish of course, part of the “artier-than-thou” virus which afflicts too great a percentage of photo mavens across the medium. As such, it can be dismissed for the prissy claptrap that it is. Strangely, the real truth about photographing animals in a zoo is that the conditions are anything but controlled.

We’ve all been there: negotiating focuses through wire mesh, dealing with a mine field of wildly contrasting light, and, in some dense living environments, just locating the ring-tailed hibiscus or blue-snouted croucher. Coming away with anything can take the patience of Job and his whole orchestra.Then there’s the problem of composing around the most dangerous visual obstacle, a genus known as Infantis Terribilis, or Other People’s Kids. Oh, the horror.Their bared teeth. Their merciless aspect. Their Dipping-Dots-smeared shirts. Brrr…

In short, to consider it “easy” to take pictures of animals in a zoo is to assert that it’s a cinch to get the shrink wrap off a DVD in less than an afternoon….simply not supported by the facts on the ground.

So, no, if you must take your camera to a zoo, shoot your kids instead of trying to coax the kotamundi out of whatever burrow he’s…burrowed into. Better yet, shoot fake animals. Make the tasteless trinkets, overpriced souvies and toys into still lifes. They won’t hide, you can control the lighting, and, thanks to the consistent uniformity of mold injected plastic, they’re all really cute. Hey, better to come home with something you can recognize rather than trying to convince your friends that the bleary, smeary blotch in front of them is really a crown-breasted, Eastern New Jersey echidna.

Any of those Dipping Dots left?

THE NON-EVENT EVENT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVENT PHOTOGRAPHY IS ONE OF THE MOST FORMALIZED MEANS OF MAKING PICTURES, a pure mission where there is usually only one “official” story being told. A happy wedding. A formal ceremony. A tearful farewell. We expect cameras to be more or less pictorial recorders at certain august moments in our lives, and anyone charged with performing that recording task is usually not expected to also serve up interesting or odd sidebars on human behavior along with the certified images we sent them to get. Event photography is not news, and may not even be persuasive human interest. It is a document, and a rather staged and stiff one at that.

But that’s what’s rewarding about being the non-official photographer at an event. It’s someone else’s job to make sure the crucial toast, the first dance, or the lowering of the casket is captured for posterity. Everyone else with a camera is free to do what photography is really about most of the time. There’s little opportunity for interpretation in the “important” keepsake shots that everyone wants, but there’s all kind of creative wiggle room in the stuff that’s considered unimportant.

I recently attended a wedding at which every key feature of the proceedings was exhaustively catalogued, and, about two hours in, I wanted to seek out something unguarded, loose, human, if you will. The image seen here of a bored hired man doing standby duty on the photo booth was just what I was seeking. I don’t know if it’s the quaint arrangement of legs and feet inside the booth or his utter look of indifference on his face as he stoically mans his post, but something about the whole thing struck me as far funnier than the groomsmen’s toasts or the sight of yet one more bride getting a faceful of cake.

I was only armed with a smartphone, but the reception hall was flooded with light at midday so the shot was far from a technical stretch. The image you see is pretty much as I took it, except for a faux-Kodachrome filter added to give it a bit of a nostalgic color wash, as well as counteracting the bluish cast of the artificial lighting. I also did some judicious guest-cropping to cut down on distraction.

Taking pictures at someone else’s event is a great gig. No expectations, no “must have” shots, and you don’t even have to care if you got the bride’s good side. Irresponsibility can be relaxing. Especially with an open bar.

SETTING THE CAPTIVES FREE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’D LIKE TO ERADICATE THE WORD “CAPTURE” FROM MOST PHOTOGRAPHIC CONVERSATIONS. It suggests something stiff or inflexible to me, as if there is only one optimum way to apprehend a moment in an image. Especially in the case of portraits, I don’t think that there can be a single way to render a face, one perfect result that says everything about a person in a scant second of recording. If I didn’t capture something, does that mean my subject “got away” in some way, eluded me, remains hidden? Far from it. I can take thirty exposures of the same face and show you thirty different people. The word has become overused to the point of meaningless.

We are all conditioned to think along certain bias lines to consider a photograph well done or poorly done, and those lines are fairly narrow. We defer to sharpness over softness. We prefer brightly lit to mysteriously dark. We favor naturalistically colored and framed recordings of subjects to interpretations that keep color and composition “codes” fluid, or even reject them outright. It takes a lot of shooting to break out of these strictures, but we need to make this escape if we are to move toward anything approaching a style of our own.

I remember being startled in 1966 when I first saw Jerry Schatzberg’s photograph of Bob Dylan on the cover of the Blonde On Blonde album. How did the editor let this shot through? It’s blurred. It’s a mistake. It doesn’t…..wait, I can’t get that face out of my head. It’s Bob Dylan right now, so right now that he couldn’t be bothered to stand still long enough for a snap. The photo really does (last time I say this) capture something fleeting about the electrical, instantaneous flow of events that Dylan is swept up in. It moves. It breathes. And it’s more significant in view of the fact that there were plenty of pin-sharp frames to choose from in that very same shoot. That means Schatzberg and Dylan picked the softer one on purpose.

There are times when one 10th of a second too slow, one stop too small, is just right for making the magic happen. This is where I would usually mention breaking a few eggs to make an omelette, but for those of you on low-cholesterol diets, let’s just say that n0 rule works all the time, and that there’s more than one way to skin (or capture) a cat.

AVOIDING THE BURN

AS A PHOTOGRAPHER, YOU CAN EMPATHIZE WITH THAT FAMOUS MOTH AND HIS FATAL FASCINATION with a candle flame….especially if you’ve ever flirted too close to the edge of a blowout with window light. You want to gobble up as much of that golden illumination as possible without singeing your image with a complete white-hot loss of detail. Too much of a good thing and all that.

However, a window glowing with light is one of the most irresistible of candies for a shooter, and you can fill up a notebook with attempted end-arounds and tricks to harvest it without getting burned. Here’s one cheap and easy way:

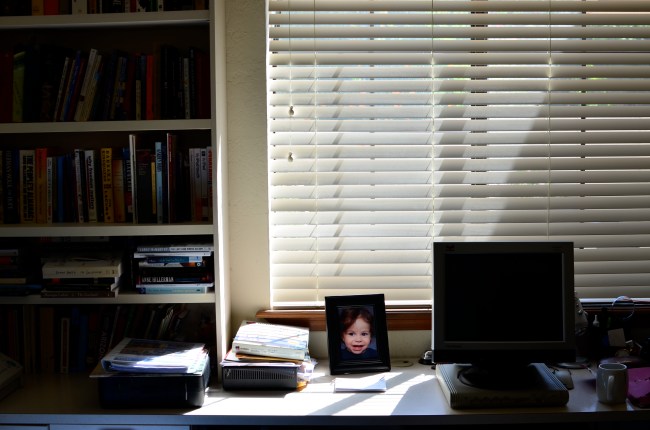

In this first attempt to capture the early morning shadows and scattered rays in my office at 1/100 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, you’ll see that the window is a little too hot, and that nearly everything ahead of the window is rendered into a silhouette. And that’s a shame, since the picture, to me, should be not only about the window light, but also its role in partially lighting a dark room. I don’t want to make an HDR here, since that will completely over-detail the stuff in the dark and look un-natural. All I really need is a hint of room light, as if a small extra bit of detail has been illuminated by the window, but just that….a small bit.

In the second attempt, I have actually halved the shutter speed to 1/200 to underexpose the window, but have also used my on-camera flash with a bounce card to ricochet a little light off the ceiling. I am almost too far away for the flash to be of any real strength, but that’s exactly what I’m looking for: I want just a trace of it to trail down the bookshelf, giving me some really mild color and allowing a few book titles to be readable. The bounce plus the distance has weakened the flash to the point that it plausibly looks as if the illumination is a result of the window light. And since I’ve underexposed the window, even the wee bit of flash hasn’t blown out the slat detail from the blinds.

Overall, this is a cheap and easy fix, happens in-camera, and doesn’t call attention to itself as a technique. There are two kinds of light: the light that is natural and the light that can be made to appear natural. If you can make the two work smoothly together, you can fly close to the flame while avoiding the burn.

THE FULLNESS OF EMPTY

By MICHAEL PERKINS SCIENCE TELLS US THAT SOME HUSBANDS HEAR THE QUESTION, “DID YOU TAKE THE TRASH OUT?” more often than any other phrase over the course of their married life. If you are an intrepid road warrior, you may hear more of something like “do you know where you’re going?” or “why don’t you just stop and ask for directions?”. If you’re a less than optimum companion, the most frequently heard statement might be along the lines of “and just where have you been?”. For me, at least when I have a camera in my hands, it’s always been “why don’t you ever take pictures of people?”

Why, indeed.

Of course, I contend that, if you were to take a random sample of any 100 of my photographs, there would be a fair representation of the human animal within that swatch of work. Not 85% percent, certainly, but you wouldn’t think you were watching snapshots from I Am Legend. However, I can’t deny that I have always seen stories in empty spaces or building faces, stories that may or may not resonate with everyone. It’s a definite bias, but it’s one of the closest things to a style or a vision that I have.

I think that absent people, as measured in their after-echoes in the places where they have been, speak quite clearly, and I am not alone in this view. Putting a person that I don’t even know into an image, just to demonstrate scope or scale, can be, to me, more dehumanizing than taking a picture without a person in it. My people-less photos don’t strike me as lonely, and I don’t feel that there is anything “missing” in such compositions. I can see these folks even when they are not there, and, if I do my job, so can those who view the results later.

Are such photographs “sad”, or merely a commentary on the transitory nature of things? Can’t you photograph a house where someone no longer lives and conjure an essence of the energy that once dwelt within those walls? Can’t a grave marker evoke a person as well as a wallet photo of them in happier times? I ask myself these questions, along with other crucial queries like, “what time is the game on?” or, “what do you have to do to get a beer in this place?” Some answers come quicker than others.

I can’t account for what amounts to “sad” or “lonely” when someone else looks at a picture. I try to take responsibility for the pictures I make, but people, while a key part of each photographic decision, sometimes do not need to serve as the decisive visual component in them. The moment will dictate. So, my answer to one of life’s most persistent questions is a polite, “why, dear, I do take pictures of people.”

Just not always.

TURN THE PAGE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’M VERY ACCUSTOMED TO BEING STOPPED IN MY TRACKS AT A PHOTOGRAPH THAT EVOKES A BYGONE ERA: we’ve all rifled through archives and been astounded by a vintage image that, all by itself, recovers a lost time.

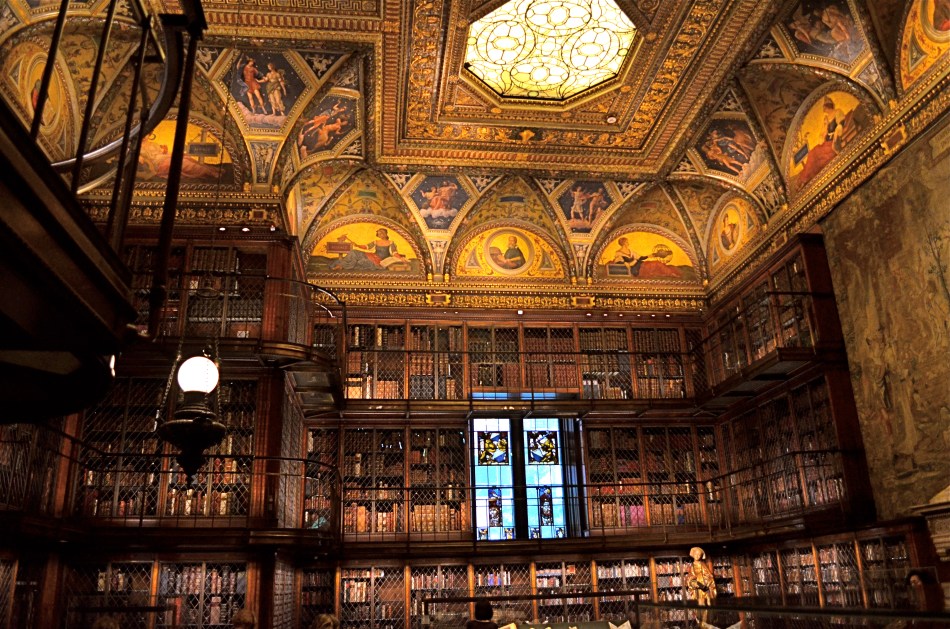

It’s a little more unsettling when you experience that sense of time travel in a photo that you just snapped. That’s what I felt several weeks ago inside the main book trove at the Morgan Library in New York. The library itself is a tumble through the time barrier, recalling a period when robber barons spent millions praising themselves for having made millions. A time of extravagant, even vulgar displays of success, the visual chest-thumping of the Self-Made Man.

The private castles of Morgan, Carnegie, Hearst and other larger-than-life industrialists and bankers now stand as frozen evidence of their energy, ingenuity, and avarice. Most of them have passed into public hands. Many are intact mementos of their creators, available for view by anyone, anywhere. So being able to photograph them is not, in itself, remarkable.

A little light reading for your friendly neighborhood billionaire. Inside the Morgan Library in NYC.

No, it’s my appreciation of the fact that, today,unlike any previous era in photography, it’s possible to take an incredibly detailed, low-light subject like this and accurately render it in a hand-held, non-flash image. This, to a person whose life has spanned several generations of failed attempts at these kinds of subjects, many of them due to technical limits of either cameras, film, or me, is simply amazing. A shot that previously would have required a tripod, long exposures, and a ton of technical tinkering in the darkroom is just there, now, ready for nearly anyone to step up and capture it. Believe me, I don’t dispense a lot of “wows” at my age, over anything. But this kind of freedom, this kind of access, qualifies for one.

This was taken with my basic 18-55mm kit lens, as wide as possible to at least allow me to shoot at f/3.5. I can actually hand-hold fairly steady at even 1/15 sec., but decided to play it safe at 1/40 and boost the ISO to 1000. The skylight and vertical stained-glass panels near the rear are WINOS (“windows in name only”), but that actually might have helped me avoid a blowout and a tougher overall exposure. So, really, thanks for nothing.

On of my favorite Twilight Zone episodes, the one about Burgess Meredith inheriting all the books in the world after a nuclear war, with sufficient leisure to read his life away, was entitled “Time Enough At Last”. For the amazing blessings of the digital age in photography, I would amend that title by one word:

Light Enough…At Last.

THE POLAROID EFFECT

BY MICHAEL PERKINS

I’VE BEEN TRYING TO FIND A WAY TO DESCRIBE THE COMBINATION OF HOPE AND ANXIETY THAT ATTENDS MY EVERY USE OF A SMARTPHONE CAMERA. Coming, as do many geezers of my era, from a tradition of full-function, hands-on, manual cameras, I have had a tough time embracing these miraculous devices, simply because of the very intuitive results that delight most other people.

But: it’s a little more complicated than my merely being a control freak or a techno-snob.

What’s always perplexing to me is that I feel that the camera is making far too many choices that it “assumes” I will be fine with, even though, in many cases, I am flat-out amazed at how close the camera delivers the very image I had in mind in the first place. It doesn’t exactly make one feel indispensable to the process of picture-making, but that’s a bug inside my own head and I gotta deal with it.

I think what I’m feeling, most of the time, is what I call the “Polaroid Effect”. To crowd around family or friends just moments after clicking off a memory with the world’s first true instant film cameras, those bulky bricks of the Mad Men era, was to share a collectively held breath: would it work? Did I get it right? Then as now, many “serious” photographers were reluctant to trust a Polaroid over their Leicas or Rolliflexes. Debate raged over the quality of the color, the impermanence of the prints, the limited lenses, the lack of negatives, and so on. Well, said the experts, any idiot can take a picture with this.

Well, that was the point, wasn’t it? And some of us “idiots” learned, eventually, to take good pictures, and moved on to other cameras, other lenses, better pictures, a better eye. But there was that maddening wait to see if you had lucked out with those square little glimpses of life. The uncertainty of trusting this…machine to get your pictures right.

And yet look at the above image. I asked a lot in this frame, with wild amounts of burning hot sunlight, deep shadows, and every kind of contrast in between just begging for the camera to blow it. It didn’t. I’m actually proud of this picture. I can’t dismiss these devices just because they nudge me out of my comfort zone.

Smartphone cameras truly extend your reach. They go where bulkier cameras don’t go, prevent more moments from being lost, and are in a constantly upward curve of technical improvement. People can and do make astounding pictures with them, and I have to remind myself that the ultimate choice…that of what to shoot, can never be taken away just because the camera I’m holding is engineered to protect me from my own mistakes.

FALL-OFF AS LEAD-IN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

USING “LEADING LINES” TO PULL A VIEWER INTO AN IMAGE IS PRETTY MUCH COMPOSITION 101. It’s one of the best and simplest ways to overcome the flat plane of a photograph, to simulate a feeling of depth by framing the picture so the eye is drawn inward from a point along the edge, usually by use of a bold diagonal taking the eye to an imagined horizon or “vanishing point”. Railroad tracks, staircases, the edge of a long wall, the pews in a church. We all take advantage of this basic trick of engagement.

Bright light into subdued light: a natural way to pull your viewer deeper into the picture. 1/100 sec., f/1.8, ISO 650, 35mm.

One thing that can aid this lead-in effect even more is shooting at night. Artificial lighting schemes on many buildings “tell” the eye what the most important and least important features should be…where the designer wants your eye to go. This means that there is at least one angle on many city scenes where the light goes from intense to muted, a transition you can use to seize and direct attention.

This all gives me another chance to preach my gospel about the value of prime lenses in night shots. Primes like the f/1.8 35mm used for this image are so fast, and recent improvements in noiseless ISO boosts so advanced, that you can shoot handheld in many more situations. That means time to shoot more, check more, edit more, get closer to the shot you imagined. This shot is one of a dozen squeezed off in about a minute. The reduction of implementation time here is almost as valuable as the speed of the lens, and, in some cases, the fall-off of light at night can act as a more dramatic lead-in for your shots.

MINUTE TO MINUTE

Going, Going: Dusk giveth you gifts, but it taketh them away pretty fast, too. 1/40 sec., f/3.5, ISO 200, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

VOLUMES HAVE BEEN WRITTEN ABOUT THE WONDROUS PHENOMENON OF “GOLDEN HOUR“, that miraculous daily window of time between late afternoon and early evening when shadows grow long and colors grow deep and rich. And nearly all authors on the subject, whatever their other comments, reiterate the same advice: stay loose and stay ready.

Golden hour light changes so quickly that anything that you are shooting will be vastly different within a few moments, with its own quirky demands for exposure and contrast. Basic rule: if you’re thinking about making a picture of an effect of atmosphere, do it now. This is especially true if you are on foot, all alone in an area, packing only one camera with one lens. Waiting means losing.

The refraction of light through clouds, the angle of the sun as it speeds toward the horizon, the arrangement between glowing bright and super-dark….all these variables are shifting constantly, and you will lose if you snooze. It’s not a time for meditative patience. It’s a time for reactivity.

I start dusk “walkarounds” when all light still looks relatively normal, if a bit richer. It gives me just a little extra time to get a quick look at shots that may, suddenly, evolve into something. Sometimes, as in the frame above, I will like a very contrasty scene, and have to shoot it whether it’s perfect or not. It will not get better, and will almost certainly get worse. As it is, in this shot, I have already lost some detail in the front of the building on the right, and the lighted garden restaurant on the left is a little warmer than I’d like, but the shot will be completely beyond reach in just a few minutes, so in this case, I’m for squeezing off a few variations on what’s in front of me. I’ve been pleasantly surprised more than once after getting back home.

What’s fun about this particular subject is that one half of the frame looks cold, dead, “closed” if you will, while there is life and energy on the left. No real story beyond that, but that can sometimes be enough. Golden hour will often give you transitory goodies, with its more dramatic colors lending a little more heft to things. I can’t see anything about this scene that would be as intriguing in broad daylight, but here, the hues give you a little magic.

Golden hour is a little like shooting basketballs at Chuck E. Cheese. You have less time than you’d like to be accurate, and you may or may not get enough tickets for a round of Skee-Ball.

But hey.