DESTINATION VS. JOURNEY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE A WANDERING EYE. Not due to muscular weakness or marital infidelity, but to a malady particular to long-time photographers. After decades of shoots big and little, I find that I am looking for pictures nearly everywhere, so much so that, what appears to many normal people to be formless space or unappealing detail might be shaping up in my mind as My Next Project. The non-obvious sings out ever louder to me as I age, and may find its way into my pictures more often than the Celebrated Scenic Wonder, the Historically Important Site or the Big Lights In The Sky that attract 99% of the photo traffic in any given locality. Part of this has to do with having been disappointed in the past by the Giant Whatsis or whatever the key area attraction is, while being delightfully surprised by little things that, for me, deserve to be seen, re-seen, or testified to.

This makes me a lousy traveling companion at times, since I may be fixated on something merely “on the way” to what everyone else wants to see. Let’s say we’re headed to the Great Falls. Now who wants to photograph the small gravel path that leads to the road that leads to the Great Falls? Well, me. As a consequence, the sentences I hear most often, in these cases, are variations on “are you coming?“, “what are you looking at?” or, “Oh my God, are you stopping again????”.

Thing is, some of my favorite shots are on staircases, in hallways, around a blind corner, or the Part Of The Building Where No One Ever Goes. Photography is sometimes about destination but more often about journey. That’s what accounts for the staircase above image. It’s a little-traveled part of a museum that I had never been in, but was my escape the from gift shop that held my wife mesmerized. I began to wonder and wander, and before long I was in the land of Sir, We Don’t Allow The Public Back Here. Oddly, it’s easier to plead ignorance of anything at my age, plus no one wants to pick on an old man, so I mutter a few distracted “Oh, ‘scuse me”s and, occasionally, walk away with something I care about. Bonus: I never have any problem shooting as much as I want of such subjects, because, you know, they’re not “important”, so it’s not like queueing up to be the 7,000th person of the day doing their take on the Eiffel Tower.

Now, this is not a foolproof process. Believe me, I can take these lesser subjects and make them twice as boring as a tourist snap of a major attraction, but sometimes….

And when you hit that “sometimes”, dear friends, that’s what makes us raise a glass in the lobby bar later in the day.

REVENGE OF THE ZOO

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PURISTS IN THE ANIMAL PHOTOGRAPHY GAME OFTEN DISPARAGE IMAGES OF BEASTIES SHOT AT ZOOS, citing that they are taken under “controlled conditions”, and therefore somewhat less authentic than those taken while you are hip-deep in ooze, consumed by insects, or scratching any number of unscratchable itches. Editors won’t even consider publishing pics snapped at the local livestock lockup, as if the animals depicted in these photos somehow surrendered their union cards and are crossing a picket line to work as furry scabs .

This is all rubbish of course, part of the “artier-than-thou” virus which afflicts too great a percentage of photo mavens across the medium. As such, it can be dismissed for the prissy claptrap that it is. Strangely, the real truth about photographing animals in a zoo is that the conditions are anything but controlled.

We’ve all been there: negotiating focuses through wire mesh, dealing with a mine field of wildly contrasting light, and, in some dense living environments, just locating the ring-tailed hibiscus or blue-snouted croucher. Coming away with anything can take the patience of Job and his whole orchestra.Then there’s the problem of composing around the most dangerous visual obstacle, a genus known as Infantis Terribilis, or Other People’s Kids. Oh, the horror.Their bared teeth. Their merciless aspect. Their Dipping-Dots-smeared shirts. Brrr…

In short, to consider it “easy” to take pictures of animals in a zoo is to assert that it’s a cinch to get the shrink wrap off a DVD in less than an afternoon….simply not supported by the facts on the ground.

So, no, if you must take your camera to a zoo, shoot your kids instead of trying to coax the kotamundi out of whatever burrow he’s…burrowed into. Better yet, shoot fake animals. Make the tasteless trinkets, overpriced souvies and toys into still lifes. They won’t hide, you can control the lighting, and, thanks to the consistent uniformity of mold injected plastic, they’re all really cute. Hey, better to come home with something you can recognize rather than trying to convince your friends that the bleary, smeary blotch in front of them is really a crown-breasted, Eastern New Jersey echidna.

Any of those Dipping Dots left?

ANATOMY OF A BOTCH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE SHOULD BE A MIRROR-IMAGE, “NEGATIVE” COOKBOOK FOR EVERY REGULAR ONE PUBLISHED, since there are recipes for inedible failures, just as surely as there are ones for gustatory delights. It might be genuinely instructive to read an article called How To Turn A Would-Be Apple Pie Into A Shapeless Heap Of Glop or You, Too Can Make Barbecue Ribs Look Like The Aftermath Of A Cremation. So too, in photography, I believe I could easily pen an essay called How To Take Pictures That Make It Seem That You Never Touched A Camera Before.

In fact…..

In recent days, I’ve been giving myself an extra welt or two with the flagellation belt in horrified reaction to a shoot that I just flat-out blew.It was a walk through a classic hotel lobby, a real “someday” destination for myself that I finally got to visit and wanted eagerly to photograph. Thing is, none of that desire made it into the frames. Nor did any sense of drama, art, composition, or the basics of even seeing. It’s rare that you crank off as many shots as I did on a subject and wind up with a big steaming pile of nothing to show for it, but in this case, I seem to have been all thumbs, including ten extra ones where my toes should be.

So, if I were to write a negative recipe for a shoot, it would certainly contain a few vital tips:

First, make sure you know nothing about the subject you’re shooting. I mean, why would you waste your valuable time learning about the layout or history of a place when you can just aimlessly wander around and whale away? Maybe you’ll get lucky. Yeah, that’s what makes great photographs, luck.

Enjoy the delightful surprise of discovering that there is less light inside your location than inside the fourth basement of a coal mine. Feel free to lean upon your camera to supply what you don’t have, i.e., a tripod or a brain. Crank up the ISO and make sure that you get something on the sensor, even if it’s goo and grit. And shoot near any windows you have, since blowouts look so artsy contrasted with pitch blackness.

Resist the urge to have any plan or blueprint for your shooting. Hey, you’re an artist. The brilliance will just flow as you sweep your camera around. Be spontaneous. Or clueless. Or maybe you can’t tell the difference.

Stir vigorously and for an insane length of time with a photo processing program, trying to manipulate your way to a useful image. You won’t get there, but life is a journey, right? Even when you’re hopelessly lost in a deep dark forest.

************************

You could say that I’m being too Catholic about this, and I would counter that I’m not being Catholic enough.

Until I do penance.

Gotta go back someday and do it right.

And make something that really cooks.

SET AND SHOOT

Shooting manually means learning to trust that you can capture what you see. 1/160 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AUTOMODES ON CAMERAS ARE SUPPOSED TO AFFORD THE PHOTOGRAPHER AN ENHANCED SENSE OF COMFORT AND SAFETY, since, you know, you’re protected from your very human errors by the camera’s loving, if soulless, oversight. Guess wrong on a shutter speed? The auto has your back. Blow the aperture? Auto is on the case. And you always get acceptable pictures.

That is, if you can put your brain on automode as well.

Okay, that statement makes the top ten list for most arrogant openings in all of Blogdom, 2014. But I stand by it. I don’t think you should get comfortable with your equipment calling the shots. However, getting comfortable with your equipment’s limits and strengths, and gradually relying on your own experience for consistent results through exploitation of that knowledge….now that’s another thing entirely. It’s the difference between driving cross-country on cruise control and knowing, from years of driving, where in the journey your car can shine, if you drive it intelligently.

Photographers call some hunks of glass their “go-to” lenses, since they know they can always get something solid from them in nearly any situation. And while we all tend to wander around aimlessly for years inside Camera Toyland, picking up this lens, that filter, those extenders, we all, if we shoot enough for a long time, settle back into a basic gear setup that is reliable in fair weather or foul.

This is better than using automodes, because we have chosen the setups and systems that most frequently give us good product, and we have picked up enough wisdom and speed from making thousands of pictures with our favorite gear that we can “set and shoot”, that is, calculate and decide just as quickly as most people do with automodes…..and yet we keep the vital link of human input in the creative chain.

Like most, I have my own “go-to” lens and my own “safe bet” settings. But, just as you save time by not trying to invent the wheel every time you step up, you likewise shouldn’t be averse to greasing an old wheel to make it spin more smoothly.

How about that, I also made the top ten list for unwieldy metaphors.

A good day.

TAKING FLIGHT ONCE MORE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE CHARGES GIVEN TO ALL PHOTOGRAPHERS IS TO MARK THE PASSAGE OF TIME, to chronicle and record, to give testimony to a rapidly vanishing world. Certainly interpretation, fantasy, and other original conceptions are equally important for shooters, but there has been a kind of unspoken responsibility to use the camera to bear witness. This is especially difficult in a world bent on obliterating memory, of dismantling the very sites of history.

Humorist and historian Bill Bryson’s wonderful book, One Summer: America 1927 frames the amazing news stories of its title year around its most singular event, the solo transatlantic flight of Charles A. Lindbergh. A sad coda to the story reveals that nothing whatever remains of Roosevelt Field, the grassy stretch on Long Island from which the Lone Eagle launched himself into immortality, with the exception of a small plaque mounted on the back of an escalator in the mall that bears the field’s name. Last week, hauled along on a shopping trip to the mall with relatives, I made my sad pilgrimage to said plaque, lamenting, as Bryson did, that there is nothing more to photograph of the place where the world changed forever.

Then I got a little gift.

The mall is under extensive renovation as I write this, and much of the first floor ceiling has been stripped back to support beams, electrical systems and structural gridwork. Framed against the bright bargains in the mall shops below, it’s rather ugly, but, seen as a whimsical link to the Air Age, it gave me an idea. All wings of the Roosevelt Field mall feature enormous skylights, and several of them occur smack in the middle of some of the construction areas. Composing a frame with just these two elements, a dark, industrial space and a light, airy radiance, I could almost suggest the inside of a futuristic aerodrome or hangar, a place of bustling energy sweeping up to an exhilarating launch hatch. To get enough detail in this extremely contrasty pairing, and yet not add noise to the darker passages, I stayed at ISO 100, but slowed to 1/30 sec. and a shutter setting of f/3.5. I still had a near-blowout of the skylight, saving just the grid structure, but I was really losing no useful detail I needed beyond blue sky. Easy choice.

Thus, Roosevelt Field, for me, had taken wing again, if only for a moment, in a visual mash-up of Lindbergh, Flash Gordon, Han Solo, and maybe even The Rocketeer. In aviation, the dream’s always been the thing anyway.

And maybe that’s what photography is really for…trapping dreams in a box.

LIGHT DECAY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WE HAVE PROVEN OURSELVES TO BE A SPECIES THAT HATES TO BE SENT TO BED. Night life being a kind of “second shift” in most of the modern world, we really never lock up our cities for the evening, and that has changed how those cities exist for photographers.

Here’s both the good and bad news: there is plenty of light available after dark in most towns. Good if you want the special mix of neon, tube glow and LED burn that sculpts the contours of most towns post-sundown. Bad if you really want to see cities as special entities defined by shadow, as places where dark is a subtle but aesthetically interesting design element. In many mega-cities, we have really banished the dark, going beyond essential illumination to a bleachingly bright blast of light which renders everything, big and small, in the same insane mutation of color and tone. Again, this is both good and bad, depending on what kind of image you want.

Midtown Manhattan, downtown Atlanta, and anyplace Tokyo are examples of cities that are now a universe away from the partial night available in them just a generation ago. A sense of architectural space beyond the brightest areas of light can only be sensed if you shoot deep and high, framing beyond the most trafficked structures. Sometimes there is a sense of “light decay”, of subtler illumination just a block away or a few stories higher than what’s seen at the busiest intersections. Making images where you can watch the light actually fade and recede adds a little dimension to what would otherwise be a fairly flat feel that overlit streets can generate.

Photography is often a matter of harnessing or collecting extra light when it’s scarce. Turns out that having too much of it is a creative problem in the opposite direction.

SETTING THE CAPTIVES FREE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’D LIKE TO ERADICATE THE WORD “CAPTURE” FROM MOST PHOTOGRAPHIC CONVERSATIONS. It suggests something stiff or inflexible to me, as if there is only one optimum way to apprehend a moment in an image. Especially in the case of portraits, I don’t think that there can be a single way to render a face, one perfect result that says everything about a person in a scant second of recording. If I didn’t capture something, does that mean my subject “got away” in some way, eluded me, remains hidden? Far from it. I can take thirty exposures of the same face and show you thirty different people. The word has become overused to the point of meaningless.

We are all conditioned to think along certain bias lines to consider a photograph well done or poorly done, and those lines are fairly narrow. We defer to sharpness over softness. We prefer brightly lit to mysteriously dark. We favor naturalistically colored and framed recordings of subjects to interpretations that keep color and composition “codes” fluid, or even reject them outright. It takes a lot of shooting to break out of these strictures, but we need to make this escape if we are to move toward anything approaching a style of our own.

I remember being startled in 1966 when I first saw Jerry Schatzberg’s photograph of Bob Dylan on the cover of the Blonde On Blonde album. How did the editor let this shot through? It’s blurred. It’s a mistake. It doesn’t…..wait, I can’t get that face out of my head. It’s Bob Dylan right now, so right now that he couldn’t be bothered to stand still long enough for a snap. The photo really does (last time I say this) capture something fleeting about the electrical, instantaneous flow of events that Dylan is swept up in. It moves. It breathes. And it’s more significant in view of the fact that there were plenty of pin-sharp frames to choose from in that very same shoot. That means Schatzberg and Dylan picked the softer one on purpose.

There are times when one 10th of a second too slow, one stop too small, is just right for making the magic happen. This is where I would usually mention breaking a few eggs to make an omelette, but for those of you on low-cholesterol diets, let’s just say that n0 rule works all the time, and that there’s more than one way to skin (or capture) a cat.

IT’S UNNATURAL, NATURALLY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST FREEING PARTS OF PICTURE MAKING IS RELEASING YOURSELF FROM THE RIGIDITY OF REALITY. Wait. What is he babbling about? Don’t photographers specialize in reality?

Well, yeah, the photographers who work at the DMV, the city jail and immigration do. Also the guy in Wal-mart HR who made your first employee badge. Other than that, everyone is pretty much rendering the world the way they see it right this minute, with more revisions or re-thinks coming tomorrow. And beyond.

Color processing, once the sole domain of the “photo finishers” has now been taken back in-house by pretty much everyone, and, even before you snap the shutter, there are fat stacks of options you can exercise to recast the world in your own image.

The practice of bracketing shots has made a bit of a comeback since the advent of High Dynamic Range, or HDR processing. You know the drill: shoot any number of shots of the same subject with varying exposure times, then blend them together. But bracketing has been a “best practice” among shooters for decades, especially in the days of film, where you took a variety of exposures of the same scene so you had coverage, or the increased chance that at least one of the frames was The One. Today, it still makes sense to give yourself a series of color choices by the simple act of taking multiple shots with varying white balances. You can already adjust WB to compensate for the color variances of brilliant sun, incandescent bulbs, tube lights, or shade for a more “natural” look. But using white balance settings counter-intuitively, that is, against “nature”, can give your shots a variety of tonal shifts that can be dramatic in their own right.

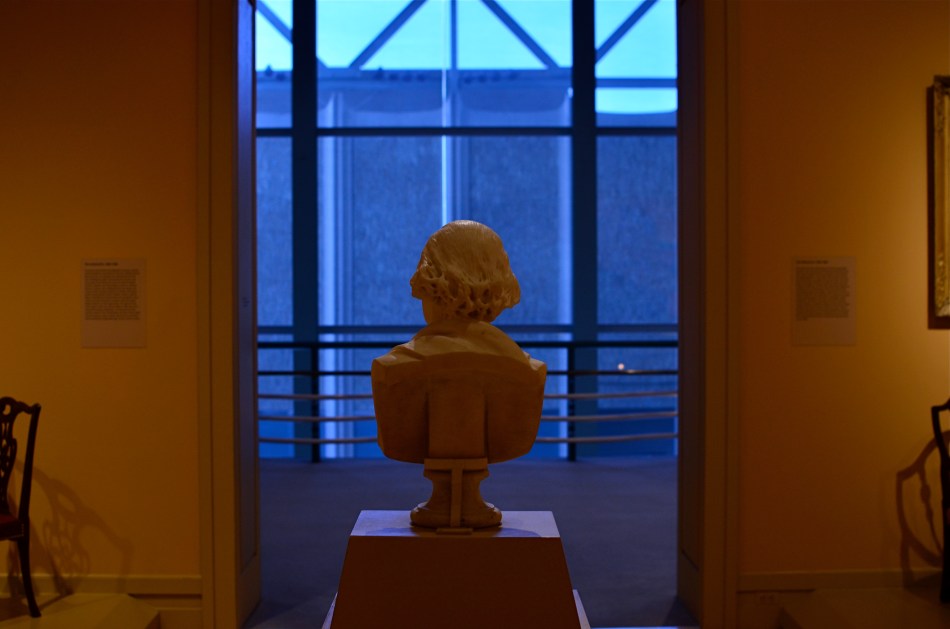

In the image above, the normal color balance of the gallery entrance would have rendered the bust off-white and the outer vestibule a light grey. Shooting on a tungsten setting when the prevailing light was incandescent gave the interior room a creamy orange look and amped the vestibule into deep blue, setting the two areas sharply off against each other and creating a kind of “end of day” aspect. I shot this scene with about five different white balances and kept the one I liked. Best of all, a comparison of all my choices could be reviewed in a minute and finished by the time the shutter clicked. Holy instant gratification, Batman.

STUPIDLY WISE

Blendon Woods, Columbus, Ohio, 1966. I usually had to shoot an entire roll of film to even come this close to making a useable shot.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IGNORANCE, IN PHOTOGRAPHY, CERTAINLY IS NOT BLISS. However, exposure to that selfsame know-nothing-ness can lead to a kind of bliss, since it can eventually lead you to excellence, or at least improvement. Here and now, I am going to tell you that all the photographic tutorials and classes in history cannot teach you one millionth as much as your own rotten pictures. Period.

Trick is, you have to keep your misbegotten photographic children, and keep them close. Love them. Treasure the hidden reservoir of warnings and no-nos they contain and mine that treasure for all it’s worth. Of course, doing this takes real courage, since your first human instinct, understandingly, will be to do a Norman Bates on them: stab them to death in the shower and bury their car in the swamp out back.

But don’t.

I have purposely kept the results of the first five rolls of film I ever shot for over forty years now. They are almost all miserable failures, and I mean that with no aw-shucks false modesty whatever. I am not exaggerating when I tell you that these images are the Fort Knox of ignorance, an ignorance taller than most minor mountain ranges, an ignorance that, if it was used like some garbage to create energy, could light Europe for a year. We’re talking lousy.

But mine was a divine kind of ignorance. At the age of fourteen, I not only knew nothing, I could not even guess at how much nothing I knew. It’s obvious, as you troll through these Kodak-yellow boxes of Ektachrome slides, that I knew nothing of the limits of film, or exposure, or my own cave-dweller-level camera. Indeed, I remember being completely mystified when I got my first look at my slides as they returned from the processor (an agonizing wait of about three days back then), only to find, time after time, that nothing of what I had seen in my mind had made it into the final image. It wasn’t that dark! It wasn’t that color! It wasn’t…..working. And it wasn’t a question of, “what was I thinking?”, since I always had a clear vision of what I thought the picture should be. It was more like, “why didn’t that work?“, which, at that stage of my development, was as easy to answer as, say, “why don’t I have a Batmobile?” or “why can’t I make food out of peat moss?”

Different woods, different life. But you can’t get here without all the mistakes it builds on. 1/400 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

But holding onto the slides over the years paid off. I gradually learned enough to match up Lousy Slide “A” with Solution”B”, as I learned what to ask of myself and a camera, how to make the box do my bidding, how to build on the foundation of all that failure. And the best thing about keeping all of the fizzles in those old cartons was that I also kept the few slides that actually worked, in spite of a fixed-focus, plastic lens, light-leaky box camera and my own glorious stupidity. Because, since I didn’t know what I could do, I tried everything, and, on a few miraculous occasions, I either guessed right, or God was celebrating Throw A Mortal A Bone Day.

Thing is, I was reaching beyond what I knew, what I could hope to accomplish. Out of that sheer zeal, you can eventually learn to make photographs. But you have to keep growing beyond your cameras. It’s easy when it’s a plastic hunk of garbage, not so easy later on. But you have to keep calling on that nervy, ignorant fourteen-year-old, and giving him the steering wheel. It’s the only way things get better.

You can’t learn from your mistakes until you room with them for a semester or two. And then they can teach you better than anyone or anything you will ever encounter, anywhere.

ON SECOND THOUGHT…OR THIRD

I really preferred this as the color shot it originally was. Until I didn’t. Changing my mind took seconds.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST AMAZING BY-PRODUCTS OF DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY, a trend still evolving across both amateur and professional ranks, is a kind of tidal return to black-and-white imaging. The sheer volume of processing choices, both in-and-out-of-camera, have made at least dabbling in monochrome all but inevitable for nearly everyone, reversing a global trend toward near exclusive use of color that was decades in the making. At one point, to be sure, we chose black and white out of necessity. Then we embraced color and relegated B&W to the dustbin of history. Now, we elect to use it again, and increasing numbers, simply because everything technical is within our reach, cheaply and easily.

Looking back, it’s amazing how long it took for color to take hold on a mass scale. Following decades of wildly uneven experimentation and dozens of processes from Victorian hand-tinting to the Autochromes of the early 1900’s, stable and affordable color film came to most of us by the end of the 1930’s. However, there was a reluctance, bearing on tantrum, among “serious” photographers to embrace it for several more decades. This article from the Life magazine Library of Photography, a history-tutorial series from the 1970’s, discusses what can only be called photography’s original anti-color bias:

Although publishers and advertisers enhanced their messages with pictures in color during the first few decades of the color era, most influential critics and museum curators persisted in regarding color photographs as “calendar art”. Color, they felt, was, at best, merely decorative, suitable, perhaps, for exotic or picturesque subjects, but a gaudy distraction in any work with “serious” artistic goals.

Of course, for years, color printing and processing was also unwieldy and expensive, scaring away even those few artists who wanted to take it on. Still, can you imagine, today, anyone holding the belief that any kind of processing was a “gaudy distraction” rather than just one more way to envision an image? Color was once seen by serious photographers as an element of the commercial world, therefore somehow..suspect. Fashion and celebrity photography had not yet been seen as legitimate members of the photo family, and their explosive use of color was almost thought of as a carnival effect. Cheap and vulgar.

Of course, once color became truly ubiquitous, sales of monochromatic film plummeted, and, for a time, black-and-white found itself on the bottom bunk, minimized as somehow less than color. In other words, we took the same blinkered blindness and just turned it on its head. Dumb times two.

Jump to today, where you can shoot, process and show images in nearly one continuous flow of energy. There are no daunting learning curves, no prohibitive expenses, no chemically charred fingertips to slow us down, or segregate one kind of photography from all others. What an amazing time to be jumping into this vast ocean of possibilities, when images get a second life, upon second thought.

Or third.

IN STEICHEN’S SHADOW

“Le Regiment Plastique”. Shot in a dark room and light-painted from the top edge of the composition. 5 seconds, f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’VE POSTED SEVERAL PIECES HERE ON “LIGHT-PAINTING”, or the practice of manually applying light to selective areas of objects during long exposures in the dark. The ability to “paint” additional colors, highlights and shadows “onto” even the most mundane materials can transform the whole light-to-dark ratio of the familiar and render it in new, if unpredictable ways. It’s kind of random and a lot of hands-on fun.

Some of the greatest transformations of ordinary objects ever seen in photography were obtained by Edward Steichen, arguably the greatest shooter in any style over the entire 20th century. Working for advertising agency J.Walter Thompson in the 1930’s, Steichen managed to romanticize everything from perfume bottles to kitchen matches to cutlery by arranging visually original ballets not only of these everyday items, but, through multiple source lighting, creating geometrically intricate patterns of shadows. His success in morphing the most common elements of our lives into fascinating abstractions remains the final word on this kind of lighting, and it’s fun to use light painting to pay tribute to it.

For my own tabletop arrangement of spoons, knives and forks, seen here, I am using clear plastic cutlery instead of silver (fashions change, alas), but that actually allows any light I paint into the scene to make the utensils fairly glow with clear definition. You can’t really paint onto or across the items, since they will pick up too much hot glare after even a few seconds, but you can light from the edge of the table underneath them, giving them plenty of shadow-casting power without whiting out. I took over 25 frames of this arrangement from various angles, since light painting is all about the randomness of effect achieved with just a few inches’ deviation in approach, and, as with all photography, the more editing choices at the end, the better.

The whole thing is really just an exercise in forced re-imagining, in making yourself consider the objects as visually new. Think of it as a puff of fresh air blowing the cobwebs out of your perception of what you “know”. Emulating even a small part of Steichen’s vast output is like me flapping my wings and trying to become a bald eagle, so let’s call it a tribute.

Or envy embodied in action.

Or both.

AVOIDING THE BURN

AS A PHOTOGRAPHER, YOU CAN EMPATHIZE WITH THAT FAMOUS MOTH AND HIS FATAL FASCINATION with a candle flame….especially if you’ve ever flirted too close to the edge of a blowout with window light. You want to gobble up as much of that golden illumination as possible without singeing your image with a complete white-hot loss of detail. Too much of a good thing and all that.

However, a window glowing with light is one of the most irresistible of candies for a shooter, and you can fill up a notebook with attempted end-arounds and tricks to harvest it without getting burned. Here’s one cheap and easy way:

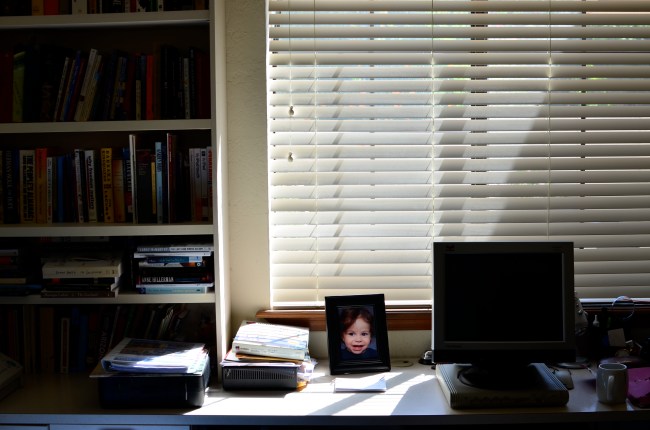

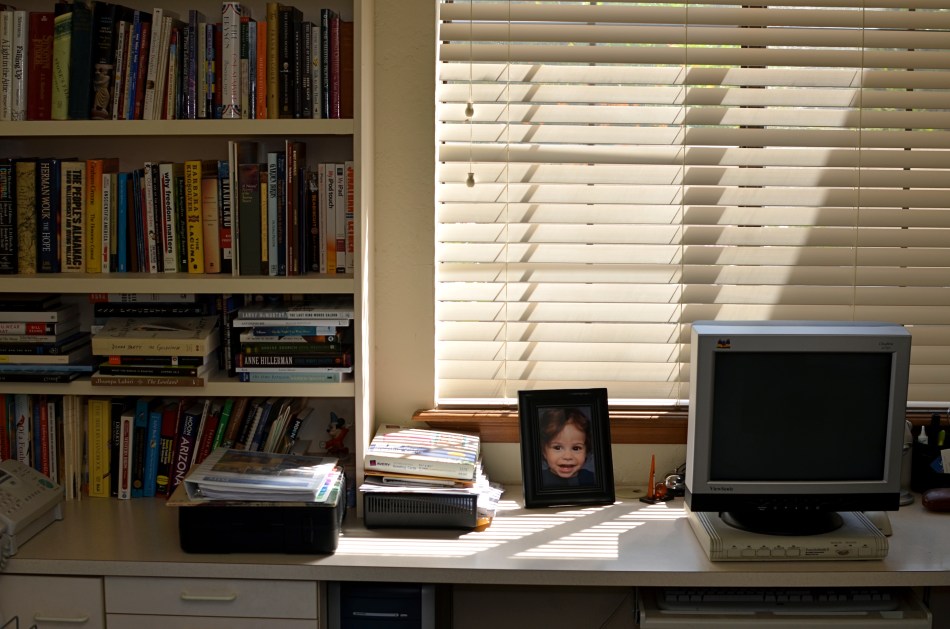

In this first attempt to capture the early morning shadows and scattered rays in my office at 1/100 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, you’ll see that the window is a little too hot, and that nearly everything ahead of the window is rendered into a silhouette. And that’s a shame, since the picture, to me, should be not only about the window light, but also its role in partially lighting a dark room. I don’t want to make an HDR here, since that will completely over-detail the stuff in the dark and look un-natural. All I really need is a hint of room light, as if a small extra bit of detail has been illuminated by the window, but just that….a small bit.

In the second attempt, I have actually halved the shutter speed to 1/200 to underexpose the window, but have also used my on-camera flash with a bounce card to ricochet a little light off the ceiling. I am almost too far away for the flash to be of any real strength, but that’s exactly what I’m looking for: I want just a trace of it to trail down the bookshelf, giving me some really mild color and allowing a few book titles to be readable. The bounce plus the distance has weakened the flash to the point that it plausibly looks as if the illumination is a result of the window light. And since I’ve underexposed the window, even the wee bit of flash hasn’t blown out the slat detail from the blinds.

Overall, this is a cheap and easy fix, happens in-camera, and doesn’t call attention to itself as a technique. There are two kinds of light: the light that is natural and the light that can be made to appear natural. If you can make the two work smoothly together, you can fly close to the flame while avoiding the burn.

THE (LATENT) BLUES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WE HAVE CONTROL OVER NEARLY EVERY PART OF THE PHOTOGRAPHIC PROCESS BUT… ACCESS. We can learn to master aperture, exposure, composition, and many other basics of picture making, but we can’t help the fact that we are typically at our shooting location for one time of day only.

Whatever “right now” may be….morning, afternoon, evening….it usually includes one distinct period in the day: the pier at sunset, the garden at break of dawn. Unless we have arranged to spend an extended stretch of time on a shoot, say, chasing the sun and shadows across a daylong period from one location at the Grand Canyon or some such, we don’t tend to spend all day in one place. That means we get but one aspect of a place…however it’s lit, whoever is standing about, whatever temporal events are native to that time of day.

Many locations that are easily shot by day are either unavailable or technically more complex after sundown. That’s why the so-called “day for night” effect appeals to me. As I had written sometime back, the name comes from the practice Hollywood has used for over a hundred years to save time and ensure even exposure by shooting in daylight and either processing or compensating in the camera to make the scene approximate early night.

In the case of the image you see up top, I have created an illusion of night through the re-contrasting and color re-assignment of a shot that I originally made as a simple daylight exposure. In such cases, the mood of the image is completely changed, since the light cues which tell us whether something is bright or mysterious are deliberately subverted. Light is the single largest determinant of mood, and, when you twist it around, it reconfigures the way you read an image. I call these faux-night remakes “latent blues”, as they generally look the way the sky photographs just after sunset.

This effect is certainly not designed to help me avoid doing true night-time exposures, but it can amplify the effect of images that were essentially solid but in need of a little atmospheric boost. Just because you can’t hang around ’til midnight, you shouldn’t have to do without a little midnight mood.

TURN THE PAGE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’M VERY ACCUSTOMED TO BEING STOPPED IN MY TRACKS AT A PHOTOGRAPH THAT EVOKES A BYGONE ERA: we’ve all rifled through archives and been astounded by a vintage image that, all by itself, recovers a lost time.

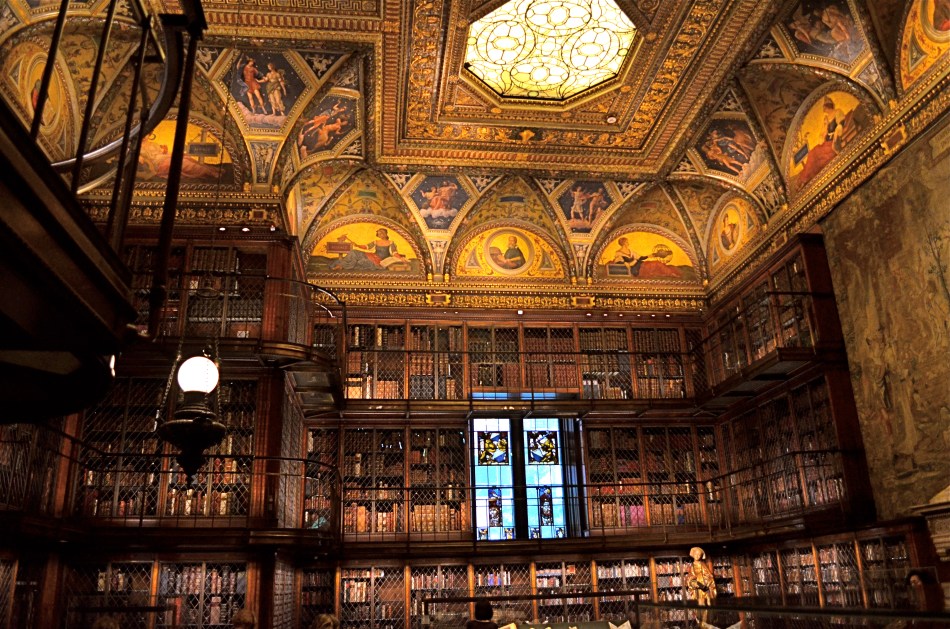

It’s a little more unsettling when you experience that sense of time travel in a photo that you just snapped. That’s what I felt several weeks ago inside the main book trove at the Morgan Library in New York. The library itself is a tumble through the time barrier, recalling a period when robber barons spent millions praising themselves for having made millions. A time of extravagant, even vulgar displays of success, the visual chest-thumping of the Self-Made Man.

The private castles of Morgan, Carnegie, Hearst and other larger-than-life industrialists and bankers now stand as frozen evidence of their energy, ingenuity, and avarice. Most of them have passed into public hands. Many are intact mementos of their creators, available for view by anyone, anywhere. So being able to photograph them is not, in itself, remarkable.

A little light reading for your friendly neighborhood billionaire. Inside the Morgan Library in NYC.

No, it’s my appreciation of the fact that, today,unlike any previous era in photography, it’s possible to take an incredibly detailed, low-light subject like this and accurately render it in a hand-held, non-flash image. This, to a person whose life has spanned several generations of failed attempts at these kinds of subjects, many of them due to technical limits of either cameras, film, or me, is simply amazing. A shot that previously would have required a tripod, long exposures, and a ton of technical tinkering in the darkroom is just there, now, ready for nearly anyone to step up and capture it. Believe me, I don’t dispense a lot of “wows” at my age, over anything. But this kind of freedom, this kind of access, qualifies for one.

This was taken with my basic 18-55mm kit lens, as wide as possible to at least allow me to shoot at f/3.5. I can actually hand-hold fairly steady at even 1/15 sec., but decided to play it safe at 1/40 and boost the ISO to 1000. The skylight and vertical stained-glass panels near the rear are WINOS (“windows in name only”), but that actually might have helped me avoid a blowout and a tougher overall exposure. So, really, thanks for nothing.

On of my favorite Twilight Zone episodes, the one about Burgess Meredith inheriting all the books in the world after a nuclear war, with sufficient leisure to read his life away, was entitled “Time Enough At Last”. For the amazing blessings of the digital age in photography, I would amend that title by one word:

Light Enough…At Last.

SOME OF MY BEST FRIENDS ARE (NOT) PHOTOGRAPHERS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE WAS A BRIEF MOMENT, WHEN PHOTOGRAPHY WAS A NOVELTY, when it was thought to be in some kind of winner-take-all death match with painting. That fake war lasted but a moment, and the two arts have fed (and fed upon) each other to varying degrees ever since. Both painting and photography have passed through phases where they were consciously or unconsciously emulating each other, and I dare say that all photographers have at least a few painter’s genes in their DNA. The two traditions just have too much to offer to live apart.

One of my favorite examples of “light sculpting”, the artistic manipulation of illumination for maximum mood, came to me not from a photographer, but from one of the finest illustrators of the early twentieth century. Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966) began his career as a painter/illustrator for fanciful fiction from Mother Goose to The Arabian Nights. Then, as color processes for periodicals became more sophisticated after 1900, he seamlessly morphed into one of the era’s premier magazine artists, working mostly for ad agencies, and most famously for his series of magnificently warm light fantasies for Edison Mazda light bulbs.

Parrish’s Mazda ads are dazzling arrangements of pastel blues, golden earth tones, dusky oranges, and hot yellows, all punched up to their most electrically fantastic limits. Years before photographers began to write about “golden hours” as the prime source of natural light, Parrish was showing us what nature seldom could, somehow making his inventions seem a genuine part of that nature. The stuff is mesmerizing. See more of his best at: http://www.parrish.artpassions.net/

During a recent trip to the high walking paths that crown Griffith Park in Los Angeles, I saw the trees and hills, at near sunset, form the perfect radiated glow of one of Parrish’s dusks. Timing was crucial: I was almost too late to catch the full effect, as shadows were lengthening and the overhanging tree near my cliffside lookout were beginning to get too shadowy. I hoped tha,t by stepping back just beyond the effective range of my on-board flash, I could fill in the front of the fence, allowing the light to decay and darken as it went back toward the tree. Too close and it would be a total blowout. Too far back, and everything near at hand would be too dark to complement the color of the sky and the hills.

After a few quick adjustments, I had popped enough color back into the foreground to make a nice authentic fake. For a moment, I was on one of Parrish’s mountain vistas, lacking only the goddesses and vestal virgins to make the scene complete. You’d think that, this close to Hollywood, you could get Central Casting to send over a few extras. In togas.

Next time.

DESTROY IT TO SAVE IT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE TIMES WHEN THE RAW VISUAL FLOOD OF INTENSE COLOR IS THE MOST INTOXICATING DRUG ON THE PLANET, at least for photographers. Sometimes you are so overcome with what’s possible from a loud riot of hues that you just assume you are going to be able to extract a coherent image from it. It happens the most, I find, with large, sprawling events: festivals, open restaurants, street fairs, carnivals, anywhere your eyeballs just go into overload. Of course there must be a great picture in all this, you promise yourself.

And there may be. But some days you just can’t find it in the sheer “Where’s Waldo”-ness of the moment. Instead, you often wind up with a grand collection of clutter and no obvious clues as to where your viewer should direct his gaze. The technical term for this is “a mess”.

I stepped in a great one the other day. It’s a local college-crowd bar in Scottsdale, Arizona, where 99% of the customers sit outside on makeshift benches, shielded from the desert sun by garish Corona umbrellas, warmed by patio heaters, and flanked by loud pennants, strings of aerial lightbulbs and neon booze ads. The place radiates fun, and, even during the daylight hours before it opens, it just screams party. The pictures should take themselves, right?

Well, maybe it would have been better if they had. As in, “leave me out of it”. As in, “someone get me a machete so I can hack away half of this junk and maybe find an image.” Try as I might, I just could not frame a simple shot: there was just too much stuff to give me a clean win in any frame. In desperation, I shot through a window to make a large cooling fan a foreground feature against some bright pennants, and accidentally did what I should have done first. I set the shot so quickly that the autofocus locked on the fan, blurring everything else in the background into abstract color. It worked. The idea of a party place had survived, but in destroying my original plan as to how to shoot it, I had saved it, sorta.

I have since gone back to the conventional shots I was trying to make, and they are still a vibrant, colorful mess. There are big opportunities in big, colorful scenes where showing “everything in sight” actually works. When it doesn’t, you gotta be satisfied with the little stories. We’re supposed to be interpreters, so let’s interpret already.

“EFFECT” VS. “EFFECTIVE”

Panoramic shots like this are no longer a three-day lab project, but an in-camera click. But what is being said in the picture?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ISN’T ANYTHING EMPTIER THAN THE PERFECT EXECUTION OF A FLAWED IDEA. And in the present effects-drenched photographic arena, where nearly any texture, color, or conception can be at least technically realized, we need, always, to be making one crucial distinction: separating what we can do from what we should do.

The basic “fixes” which come natively loaded in even the most basic cameras (filters, effects, nostalgic slathers of antique colors) suggest a broad palette of choices for the photographer looking to extend his reach through what is basically an instantaneous short cut. Fine and dandy, so far. Who, after all, wants to labor for hours to augment a shot with a particular look if that effect can be achieved at the touch of a button? Certainly no one gets into photography anymore with the understanding that they will also have to act as a chemist, and creativity need not be the exclusive playground of the scientifically elite. We all agree that the aim of photography always has and always should be the placing of all tools in as many hands as possible, etc., etc.

But waita seccint. Did I say the world tool? ……(will the recorder read that last part back….?……”placing of all tools in as many…”)… yep, tool. Ya see, that word has meaning. It does not mean an end unto itself. A fake fisheye doth not a picture make. Nor doth a quickie panorama app, a cheesy sepia filter, nor (let’s face it) the snotty habit of saying “doth”. These things are supposed to supplement the creative moment, not be a substitute for it. They are aids, not “fixes”.

This comes back to the earlier point. Of course we can simulate,imitate, or re-create certain visual conditions. But what are we actually saying in the picture? Did we use the effect to put a firm period at the end of a strong sentence, or did we use it as a smoke bomb to allow us to exit the stage before the audience gets wise to the fakery?

One of the original objections to photography, as stated by painters, was that we were handing off the actual act of visual artistry to a (gasp!) machine. A little hysterical, to be sure, but a concern is still worth addressing.

There is a soul in that machine, to be sure.

But only if we supply it.

WORK AT A DISADVANTAGE

Focus. Scale. Context. Everything’s on the table when you’re trolling for ideas. 1/100 sec., f/5.6, ISO 800, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“IS THERE NO ONE ON THIS PLANET TO EVEN CHALLENGE ME??“, shouts a frustrated General Zod in Superman II as he realizes that not one person on Earth (okay, maybe one guy) can give him a fair run for his money. Zod is facing a crisis in personal growth. He is master of his domain (http://www.Ismashedtheworld.com), and it’s a dead bore. No new worlds to conquer. No flexing beyond his comfort zone. Except, you know, for that Kryptonian upstart.

Zod would have related to the average photographer, who also asks if there is “anyone on the planet to challenge him”. Hey, we all walk through the Valley Of The Shadow Of ‘My Mojo’s Gone’. Thing is, you can’t cure a dead patch by waiting for a guy in blue tights to come along and tweak your nose. You have to provide your own tweak, forcing yourself back into the golden mindset you enjoyed back when you were a dumb amateur. You remember, that golden age when your uncertainly actually keened up your awareness, and made you embrace risk. When you did what you could since you didn’t know what you could do.

You gotta put yourself at a disadvantage. Tie one hand behind your back. Wear a blindfold. Or, better yet, make up a “no ideas” list of things that will kick you out of the hammock and make you feel, again, like a beginner. Some ways to go:

1.Shoot with a camera or lens you hate and would rather avoid. 2.Do a complete shoot forcing yourself to make all the images with a single lens, convenient or not. 3.Use someone else’s camera. 4.Choose a subject that you’ve already covered extensively and dare yourself to show something different in it. 5.Produce a beautiful or compelling image of a subject you loathe. 6.Change the visual context of an overly familiar object (famous building, landmark, etc.) and force your viewer to see it completely differently. 7.Shoot everything in manual. 8.Make something great from a sloppy exposure or an imprecise focus. 9.Go for an entire week straight out of the camera. 10.Shoot naked.

Okay, that last one was to make sure you’re still awake. Of course, if nudity gets your creative motor running, then by all means, check local ordinances and let your freak flag fly. The point is, Zod didn’t have to wait for Superman. A little self-directed tough love would have got him out of his rut. Comfort is the dread foe of creativity. I’m not saying you have to go all Van Gogh and hack off your ear. But you’d better bleed just a little, or else get used to imitating instead of innovating, repeating instead of re-imagining.

DARKNESS AS SCULPTOR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN DAYLIGHT PHOTOGRAPHY, THE DEFAULT ACTION TENDS TO BE TO SHOW EVERYTHING. Shadows in day scenes are a kind of negative reference to the illuminated objects in the frame, but it is those objects, and not the darkness, that defines space. In this way shady areas are a kind of decor, an aid to recognition of scale and depth.

At night, however, the darkness truly plays a defining role, reversing its daylight relationship to light. Dark becomes the stuff that night photos are sculpted from, creating areas that can remain undefined or concealed, giving images a sense of understatement, even mystery. Not only does this create compelling compositions of things that are less than fascinating in the daytime, it allows you to play “light director” to selectively decide how much information is provided to the viewer. In some ways, it is a more pro-active way of making a picture.

This bike shop took on drastically different qualities as the sun set. 1/40 sec., f/3.5, ISO 100, 18mm.

I strongly recommend walkabout shoots that span the complete transition from dusk to post-sunset to absolute night. Not only will the quickly changing quality of light force you to make decisions very much in-the-moment, it allows for a vast variance in the visual power of your subjects that is starkly easy to measure. It’s a great practice lab for shooting completely on manual, and, depending on the speed of your chosen lens (and greater ISO flexibility in recent cameras), makes relatively noise -free, stable handheld shots possible that were unthinkable just a few years ago. One British writer I follow recently remarked, concerning ISO, that “1600 is the new 400”, and he’s very nearly right.

So wander around in the dark. The variable results force you to shoot a lot, rethink a lot, and experiment a lot. Even one evening can accelerate your learning curve by weeks. And when darkness is the primary sculptor of a shot, lovely things (wait for the bad pun) can come to light (sorry).