AS DIFFERENT AS DAY AND NIGHT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY OFTEN PRESENTS ITSELF AS A SUDDEN, REACTIVE OPPORTUNITY, a moment in time where certain light and compositional conditions seem ripe for either recording or interpreting. In such cases there may be little chance to ponder the best way to visualize the subject at hand, and so we snap up the visualization that’s presented in the moment. It’s the kind of use-it-or-lose-it bargain we’re all acquainted with. Sometimes it yields something amazing. Other times we do the best with what we’re handed, and it looks like it.

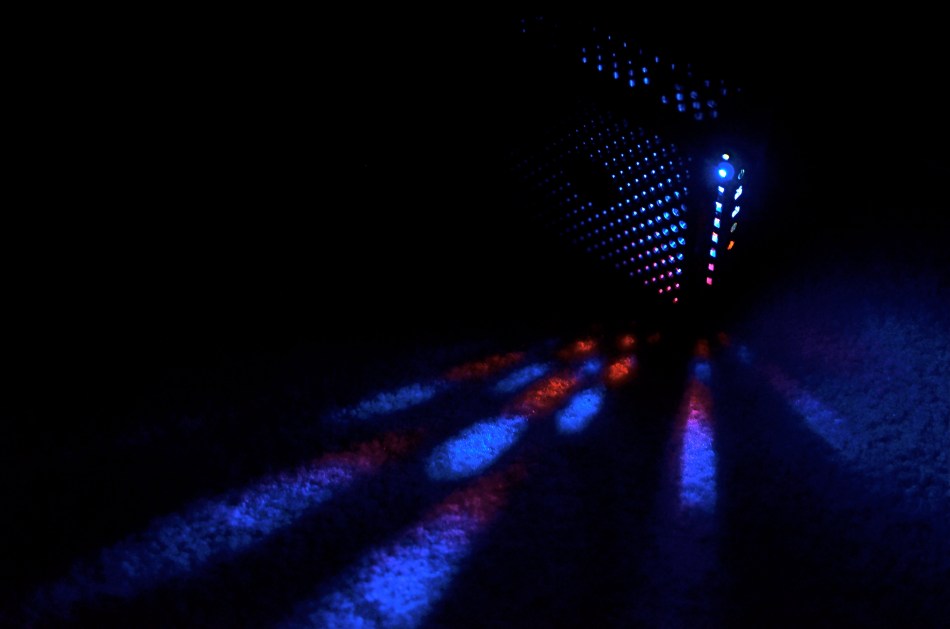

Having the option to shape light as we like takes time and deliberate planning, as anyone who has done any kind of studio set-up will attest. The stronger your conception to start with, the better chance you have of devising a light strategy for making that idea real. That’s why I regard light painting, which I’ve written about here several times, as a great exercise in building your image’s visual identity in stages. You slow down and make the photograph evolve, working upwards from absolute darkness.

Shock-Top, 2014. Light-painted with a hand-held LED over the course of a six-second exposure, at f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

To refresh, light painting refers to the selective handheld illumination of subjects for a particular look or effect. The path that your flashlight or LED takes across your subject’s contours during a tripod-mounted time exposure can vary dramatically, based on your moving your light source either right or left, arcing up or down, flickering it, or using it as a constant source. Light painting is different from the conditions of, say, a product shoot, where the idea is to supply enough light to make the image appear “normal” in a daytime orientation. Painting with light is a bit like wielding a magic wand, in that you can produce an endless number of looks as you develop your own concept of what the final image should project in terms of mood. It isn’t shooting in a “realistic” manner, which is why the best light painters can render subjects super-real, un-real, abstract or combinations of all three. Fact is, the most amazing paint-lit photos often completely violate the normal paths of natural light. And that’s fine.

In light painting, I believe that total darkness in the space surrounding your central subject is as important a compositional tool as how your subject itself is arranged. As a strong contrast, it calls immediate and total attention to what you choose to illuminate. I also think that the grain, texture and dimensional quality of the subject can be drastically changed by altering which parts of it are lit, as in the shock of wheat seen here. In daylight, half of the plant’s detail can be lost in a kind of brown neutrality, but, when light painted, its filaments, blossoms and staffs all relate boldly to each other in fresh ways; the language of light and shadow has been re-ordered. Pictorially, it becomes a more complex object. It’s actually freed from the restraints of looking “real” or “normal”.

Developed beyond its initial novelty, light painting isn’t an effect or a gimmick. It’s another technique for shaping light, which is really our aim anytime we take off our lens caps.

THE EYES (DON’T NECESSARILY) HAVE IT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

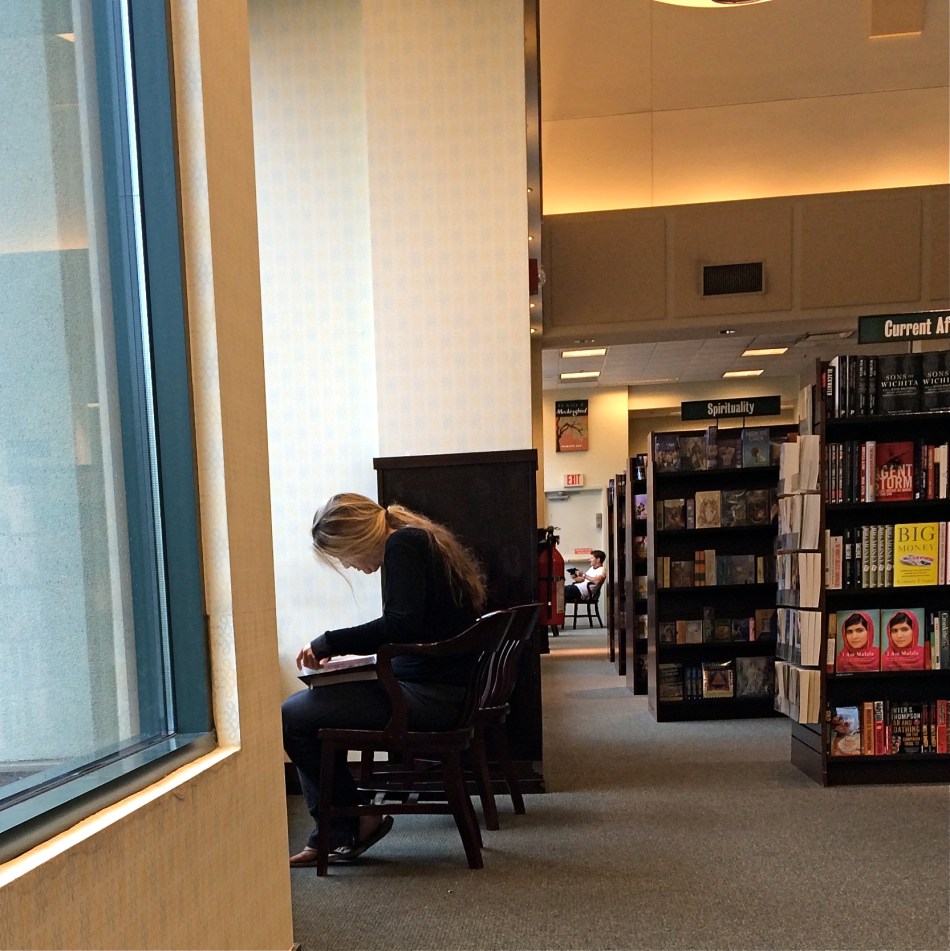

A QUICK GOOGLING OF THE PHOTOGRAPHIC UNIVERSE THESE DAYS will turn up a number of sites dedicated to “faceless portraits”, if there can, strictly speaking, be such a thing (and I believe there can). In a recent post entitled Private, Not Impersonal, I explored the phenomenon in which photographers, absent the features that most easily chronicle their subjects’ personalities, imply them, merely through body language, composition, or lighting. At the time I wrote the post, I was unaware how widespread the practice of faceless portraits had become. In fact, it’s something of a rage. Hmm. The very thought that, even by accident, I could be aligned with something hip, is, by turns, both terrifying and hilarious.

Thing is, photographs, as the famous curator John Szarkowki remarked, both conceal and reveal, and there is nothing about the full depiction of a human face that guarantees that you’re learning or knowing anything about the subject in frame. We are all to practiced at maintaining our respective masks for many portraits to be taken, ha ha, at face value. Cast your eye back through history and you will find dozens of compelling portraits, from Edward Steichen’s silhouettes of Rodin to Annie Leibovitz’ blurred dance photos of Diane Keaton, that preserve some precious element of humanity that a formal, face-on sitting cannot deliver. Call it mystery, for lack of a more precise word.

In the above frame, the subject whose face I myself never even saw gave me something wonderfully human, about reading in particular, but about enchantment in general. She is furiously busy discovering another world, a world the rest of us can only guess at, seeping up from her book. Her entire body is an inventory of emotional textures…of relaxation, attentiveness, of both being in the present and so completely someplace else. Framing her to include the negative spaces of the window, the carpet and the wider bookstore isolate her further from us, but not in a negative way. She wants to be apart; she is on a journey.

My “girl with the flaxen hair” was unaware of me, and I shot furtively and quickly to make sure I didn’t break the spell she was under. It was the least I could do in gratitude for a chance to witness her adventure. Looking back, I think she provided more than enough magic without revealing a single fragment of her face. Seeing is selecting, and I had been given all I needed to do both.

Click and be gone.

PENCIL LINE, INK LINE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MY FATHER, AS A GRAPHIC ARTIST, USED TO WARN ME ABOUT COMMITTING MYSELF TOO EARLY. Not in terms of personal relationships, but as it applied to the act of drawing. “Always lay down all your potential pencil lines first”, he advised, “and then decide which ones you want to ink.” The message was that flexibility was as valuable a drafting tool as your 2H pencil or your Rapidograph pen, that delaying your final vision often helped you eliminate the earlier drafts and their respective weaknesses. I still value that advice, as it has a current corollary in the making of my photographs, largely as a consequence of the smartphone revolution.

Once phones began packing cameras that could actually deliver an image better than a Crayola shmear on a wet cocktail napkin, photographers who still chiefly relied on their traditional cameras suddenly had the luxury of a kind of optical “sketch pad”; that is, an easy way to pre-visualize a composition with a basic machine that you could use for a study, a dress rehearsal for a more precise re-imagining with a more advanced device. For many of us, the larger display area of a phone can often “make the sale” for a shot in a more compelling way than the smaller monitor on our grown-up camera, and, at the very least, we can judge how a photo will “play” less conspicuously than by lugging about more visually obvious hardware. It’s a fast way to gather a lot of preliminary ideas, especially in locales where you’re free to come back later for the serious shoot.

I especially like trolling through vintage stores, trying to find antique items that, in themselves, make for impromptu still-life subjects. Sometimes, to be honest, I go home with a pocket full of puckey. Sometimes, I decide to go back and do a more thorough shoot of the same subject. And sometimes, as in the above image, I decide that I can live with an original “sketch” with just a little post-tweaking. The exercise does one important thing, in that it reminds you to always be shooting, or at least always thinking about shooting.

I know people who have completely stopped even carrying DSLRs and other, more substantial gear in their everyday shooting, and, while I can’t quite get there yet, I get the idea on many levels. Hey, use a fine stylus, a sharp crayon, or a charred stick, dealer’s choice. Just get the sketch.

GO OUT AND COME BACK IN AGAIN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SEPARATING ONE’S IMAGES INTO “HIT” AND “MISS” PILES is always painful, since it’s kind of like telling some of your kids that they will be power hitters in Little League while their siblings should take up…well, macrame. But self-editing, over time, is nearly as important as shooting, and the mindfulness of asking “what was I thinking” is the useful corollary to “what do I want to do next?” That don’t make it smart any less, but at least you understand the pain.

Usually I hurl photos into the “miss” box for purely technical reasons, which means that I should have known what to do and just blew it upon execution. I’m more exacting nowadays, because present-era camera make it tougher to absolutely boot a shot, although I have striven to stay ahead of the curve and make lousy pictures even in the face of rapidly advancing technology. People who think they’ve idiot-proofed their gear have never met this idiot, I boast. It’s a point of pride.

Occasionally, though, you review a shot that was okay exposure-wise, but completely got the narrative wrong. Sometimes you can recompose the shot and redress this problem, and sometimes you’re just sealed out of the airlock with no oxygen. That’s the breaks. In the original image at the top of this page is a candid of a little girl next to a horse that I thought would be charming. Cute kid, nice horsie, you get the picture. Problem is, I never really captured her essence in any of the photos I shot (trust me) and I framed so tight that I was only showing the horse’s body. First verdict on this one: thanks for playing our game, sorry to see you go, here are some lovely parting gifts.

However, as a rainy day project, the photo suddenly presented a different way for me to go. It wasn’t that I had shown too little of the horse; it was that I had shown too much of both the horse and the child. The central part of the image, taken by itself, had a narrative power that the larger frame lacked. To crop so that just a part of the girl’s small arm connected with the strong, muscular torso of the horse magnified his power by contrasting it with her fragility. I wasn’t losing the horse’s face, since it hadn’t been in the original, and losing the girl’s face actually improved the impact of the image by reducing her to an abstraction, to a symbol of innocence, gentleness, but above all, contact. We could deduce that the horse and the girl were friends. We didn’t need to see it reflected in their features.

Sometimes an image we are ready to reject is hiding a more concentrated fragment that saves the entire thing, if we are unafraid to pare away what we once saw as “essential”. It’s the go-out-and-come-back-in-again school of thought. It’s at least a seeing exercise, and you gotta flex them eye and brain muscles at every opportunity.

DESTINATION VS. JOURNEY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE A WANDERING EYE. Not due to muscular weakness or marital infidelity, but to a malady particular to long-time photographers. After decades of shoots big and little, I find that I am looking for pictures nearly everywhere, so much so that, what appears to many normal people to be formless space or unappealing detail might be shaping up in my mind as My Next Project. The non-obvious sings out ever louder to me as I age, and may find its way into my pictures more often than the Celebrated Scenic Wonder, the Historically Important Site or the Big Lights In The Sky that attract 99% of the photo traffic in any given locality. Part of this has to do with having been disappointed in the past by the Giant Whatsis or whatever the key area attraction is, while being delightfully surprised by little things that, for me, deserve to be seen, re-seen, or testified to.

This makes me a lousy traveling companion at times, since I may be fixated on something merely “on the way” to what everyone else wants to see. Let’s say we’re headed to the Great Falls. Now who wants to photograph the small gravel path that leads to the road that leads to the Great Falls? Well, me. As a consequence, the sentences I hear most often, in these cases, are variations on “are you coming?“, “what are you looking at?” or, “Oh my God, are you stopping again????”.

Thing is, some of my favorite shots are on staircases, in hallways, around a blind corner, or the Part Of The Building Where No One Ever Goes. Photography is sometimes about destination but more often about journey. That’s what accounts for the staircase above image. It’s a little-traveled part of a museum that I had never been in, but was my escape the from gift shop that held my wife mesmerized. I began to wonder and wander, and before long I was in the land of Sir, We Don’t Allow The Public Back Here. Oddly, it’s easier to plead ignorance of anything at my age, plus no one wants to pick on an old man, so I mutter a few distracted “Oh, ‘scuse me”s and, occasionally, walk away with something I care about. Bonus: I never have any problem shooting as much as I want of such subjects, because, you know, they’re not “important”, so it’s not like queueing up to be the 7,000th person of the day doing their take on the Eiffel Tower.

Now, this is not a foolproof process. Believe me, I can take these lesser subjects and make them twice as boring as a tourist snap of a major attraction, but sometimes….

And when you hit that “sometimes”, dear friends, that’s what makes us raise a glass in the lobby bar later in the day.

SAME SHIFT, DIFFERENT DAY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHS OF PERFORMANCES ARE PERHAPS MY FAVORITE STUDIES OF THE HUMAN FACE. None of the self-conscious artifice or hesitant reticence of the standard portrait shoot are present when a player, be it a violinist or pianist, is fully inside the trance of creation. Call it rapture, call it focus, but something almost holy illuminates the features when people sing or play. All the awareness of their face as a mask melts away, as all mental energy surges to the task at hand. Their faces become some other thing, and I can’t resist trying to preserve that.

I recently had a chance to shoot two performances at the same part of the same museum about

ten weeks apart. The first set of images were like walking barefoot through roses; everything worked. The second occasion, just a few days ago, was, by comparison, work, and frustrating work at that. The time of day for both sessions was the same, with mid-morning light entering the hall through cream-color curtains and softening everything to an appealing haze. My distance from the stage was also nearly the same on both days. What created the difference in my results, then, was my choice of lens, pure and simple. All of my “luck” came because the first lens was perfect for the task. All of my muttered oaths at the second occasion were due to how wrong my choice had been.

In the first case, exemplified by the mariachi band in the image at right, I used a 35mm prime, which

is simple, sharp and fast enough, at f/1.8 on the wide-open end, to give me enough light in nearly any situation. In the more recent shoot, I used a 300mm zoom, about the most opposite approach you could try. The lens cannot get any wider open than f/4.5, and shuts down all the way to f/5.6 when fully zoomed in, so, right off the bat, you’re starving yourself for light, especially in a room where most of it is behind the performers. I decided to try the 300 out of pure perverse curiosity, and from a sense of “what can I lose?”, which is a blessing, since, when the results don’t matter, you can try something, just to see what happens.

Well, I saw.

The light reduction with the 300 was more severe than I’d anticipated. Oh, sure, I could get really tight framings on the performers, but I was going to have to either slow my shutter speed to under 1/60 or jack the ISO up to undesirably high noise level, or, as it turns out, both. The contrast between light and dark was the first thing to take the hit, as tone registered in a muddy middle range with the zoom versus the sharply defined values I had gotten with the 35.

Then there was the overall softness of the 300, due largely to the small amount of camera shake on my part, which, in a zoom, is magnified several times over. In both cases, I got usable images, but whereas with the 35mm prime I had a kind of embarrassment of riches, the object with the zoom shoot was to salvage something and slave away like mad to do so.

I could easily have taken wider framed shots with the 35 (since it can’t zoom), then cropped them for tightness later, as I had on the first day. Instead, I got a lot of really tight shots of musicians that needed serious intervention to make them acceptable. But I want to emphasize that this is what experimentation is for. You put your hand on the hot stove, yell “OWWW!” and refrain from touching the hot stove in future. At the end of the second shoot, I had lost no money, no business, and very little time. That’s education on the cheap.

I don’t mind wearing the dunce cap every once in a while, if I know that, eventually, I’m going to end up in a fedora.

PRIVATE, NOT IMPERSONAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PORTRAITURE IS RATHER NARROWLY DEFINED BY MOST PHOTOGRAPHERS as an interpretation of a person’s face, the place wherein we believe that most of his/her humanity resides. The wry smile. The upturned eyebrow. The sparkling eye. It’s all there in the features, or so we seem to profess by valuing the face over nearly all other physical features.We stipulate that there are notable exceptions where the body carries most of the message, as in crowd scenes, sports action, or combat shots. But for the most part, we let the face hold the floor (and believe me, after a few misspent nights, my face has held the floor plenty of times).

It’s interesting, however, in an age where privacy has become a premiere issue, and in which the camera’s eye never blinks, that we don’t explore the narrative power of bodies as much as we do faces. The body, after all, carries out the intentions of the mind no less than does the face. It executes the physical action that the mind intends, and so creates a space that reveals that intention. Just like a face. And yet, we have a decidedly pro-face bias in our portraiture, to the point that a portrait that does not include a face is thought by some not to be a portrait at all.

But let’s keep the discussion, and our minds, open, shall we? I love to work with random crowds, and I like nothing better than to immortalizing emotions in a nice face-freeze. However, I strongly maintain that, absent those obvious visual “cues”, a body can carry a storyline all by itself, even enhance the charm or mystery involved in trying to penetrate the personality of our subjects.

Consider for a moment how many amazing nude studies you’ve seen where the subject’s face is completely, even deliberately obscured. Does the resulting image lack in power, or does the power traditionally residing in the face just transfer to the rest of the composition?

Portraits (I insist on calling them that) that are more “private” for being faceless are no more “impersonal” than if the subject was flashing the traditional “cheese!” and beaming their personality directly into the lens.

Photography is not about always getting the vantage point that we want, but maximizing the one we have at hand. And sometimes, taking away a face also strips away a mask. But beyond that, why not actually court mystery, allow ourselves to trust our audiences to supply mentally what we reserve visually?

Ask yourself: what does a photograph of understatement look like?

REVENGE OF THE ZOO

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PURISTS IN THE ANIMAL PHOTOGRAPHY GAME OFTEN DISPARAGE IMAGES OF BEASTIES SHOT AT ZOOS, citing that they are taken under “controlled conditions”, and therefore somewhat less authentic than those taken while you are hip-deep in ooze, consumed by insects, or scratching any number of unscratchable itches. Editors won’t even consider publishing pics snapped at the local livestock lockup, as if the animals depicted in these photos somehow surrendered their union cards and are crossing a picket line to work as furry scabs .

This is all rubbish of course, part of the “artier-than-thou” virus which afflicts too great a percentage of photo mavens across the medium. As such, it can be dismissed for the prissy claptrap that it is. Strangely, the real truth about photographing animals in a zoo is that the conditions are anything but controlled.

We’ve all been there: negotiating focuses through wire mesh, dealing with a mine field of wildly contrasting light, and, in some dense living environments, just locating the ring-tailed hibiscus or blue-snouted croucher. Coming away with anything can take the patience of Job and his whole orchestra.Then there’s the problem of composing around the most dangerous visual obstacle, a genus known as Infantis Terribilis, or Other People’s Kids. Oh, the horror.Their bared teeth. Their merciless aspect. Their Dipping-Dots-smeared shirts. Brrr…

In short, to consider it “easy” to take pictures of animals in a zoo is to assert that it’s a cinch to get the shrink wrap off a DVD in less than an afternoon….simply not supported by the facts on the ground.

So, no, if you must take your camera to a zoo, shoot your kids instead of trying to coax the kotamundi out of whatever burrow he’s…burrowed into. Better yet, shoot fake animals. Make the tasteless trinkets, overpriced souvies and toys into still lifes. They won’t hide, you can control the lighting, and, thanks to the consistent uniformity of mold injected plastic, they’re all really cute. Hey, better to come home with something you can recognize rather than trying to convince your friends that the bleary, smeary blotch in front of them is really a crown-breasted, Eastern New Jersey echidna.

Any of those Dipping Dots left?

BREAKING THE BOX

The picture shown here was spoiled by tilting the camera sidewise. The whole scene seems to be “running downhill”. Unless you are trying for an unusual effect, hold the camera level. – How To Make Good Pictures, c) 1943 The Eastman Kodak Company

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE CARDINAL RULES OF PHOTOGRAPHIC COMPOSITION IS THE MAINTENANCE OF A PAINTER’S VIEW OF THE WORLD, and it needs to be abandoned as irrelevant to picture-making in the current era. I’m talking about one of the Photography 101 rules we all inherited from the medium’s 19th-century beginnings, which is the unyielding reverence for “the box” as a framing device.

You know the admonition, and can recite it out of a million amateur guides: the parameters of your photo must be a dead parallel line top and bottom and two perfectly perpendicular verticals for the left and right sides. Call it the “out the window” orientation or the painter’s frame, or perhaps the “God’s in his heaven, all’s right with the world” concept of a perfect clockwork universe. Whatever the term, this unbending admonition became common to every amateur book on photographic instruction since forever. Tilting was bad. Bending the frame or composing within an abstracted version of it was really bad. Calling attention to the frame instead of letting it remain invisible was amateurish.

I’ll tell you what’s bad: doing everything the same way, forever, and expecting to grow as a photographer, or as an anything.

Framing in photography sets the visual grammar of an image. It lays out the rules of engagement as much as anything that’s contained within it. It can be an artistic statement all in itself, and needs to be thought of as a deliberate choice, no less than camera settings or subject matter. The square or rectangle is not a mathematical commandment. Like every other element of making images, it needs to justify itself for the picture at hand. What is right for this instance?

The image seen here is a very calm and unchallenging composition. I liked the small number of elements presented by the stark little porch and the rich but mysterious patch of forest. But in both the shooting and the cropping, I decided to subtly re-jigger the frame to include structural parts of the porch and the window through which I shot the scene, throwing off the perfect geometry of vertical and horizontal, resulting in a look that is a little off-kilter. I tried looking at the shot without any of these parts, and the picture looked too pat, too passive, whereas creating an imperfect square with them gave the photograph just a little edge. Not a slam-you-over-the- head effect, just a slight bit of visual punctuation.

Call it the difference between a colon and semi-colon.

As for the Eastman Kodak Company’s caution that you should maintain the standard frame unless you “are trying for an unusual effect”, well, aren’t you doing that every time you step up to bat?

If not, what’s the point?

ROAD FOOD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

Truck Driver: Give me some more of this poison you call coffee.

Waitress: I notice you’re on your third cup…

Truck Driver: I like your sugar.

They Drive By Night, Warner Brothers, 1940

AMERICANS CERTAINLY DID NOT INVENT THE IDEA OF STOPPING OFF FOR CHOW “ON THE WAY” TO WHEREVER. The roadside taverns and eateries that dot the globe in the spaces between village and town are the stuff of worldwide legend. Call it the “ye olde inn” tradition. However, in the 20th century, we Yanks did our bit in contributing to the romance of road food. Hey, you’re motoring across the country in your new Ford/Buick/Merrie Oldsmobile anyway, so you need some kind of, let’s call it grub infrastructure, laid out along the route.

Mind you, these won’t be the same restaurants where Grandma and the kids tuck in of a Sunday supper. We leave the linens to the landed gentry: simply paper napkins here, bub. The best “joints” actually resemble trailers more than restaurants, with the menu ranging from non-poisonous to “not bad”, but not much wider. Diners and dives don’t pull down Michelin stars and Zagat raves. But they do shape our traveling, and photographic, experiences. And now that we’re beyond the first great Golden Age of Motoring (maybe the only one, come to think of it), photo-documenting these decaying munch museums is a must.

I love the curvy chrome and Deco streamlining that forms the shell of many joints. I love them even more in their present state of slow disintegration,when the streamlining isn’t too straight, the chrome gives off an apologetic, latter-day patina, and all the angles don’t quite square up. My photographer’s eye likes these temples of makeshift cuisine because they are cheap and cheesy. They’re vulgar and obvious in their blinky, half-dead neon, kitschy colors and over-ripe graphics, and as Sinatra used to sing, that’s America to me. Love it.

Some of my favorite joints are far more dinosaur than diner, but, when you can squeeze off a frame or two of their fading glory, and amble inside for a five dollar cheeseburger deluxe, heck, boyo, that’s a combo plate you can’t even get at the Ritz. And if I could ever find the dazzling dame who modeled for the drawing of a waitress on the side of all those millions of ketchup squeeze bottles, that would be love at first sight.

Talk about your latter-day Mona Lisa. With fries.

CLEAN-UP ON AISLE FIVE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

TAKE ENOUGH PHOTOGRAPHS AND YOU WILL DEVELOP YOUR OWN SENSE OF “SIMPLICITY”. That is, you will arrive at your own judgement about how basic or complex a composition you need in a given situation. Some photographers are remarkable in their ability to create images that contain a mad amount of visual information. Some busy city scenes or intricate landscapes benefit wonderfully from an explosion of detail. Other shooters render their best stories by reducing elements to a bare minimum. And of course, most of us make pictures somewhere in the vast valley between those approaches.

I’m pretty accustomed to thinking of overly-busy pictures as consisting of a specific kind of “clutter”, usually defined as cramming too many objects or people into a composition. But I occasionally find that color can be a cluttering element, and that some very visually dense photos can be rendered less so by simply turning down hues, rather than rooting them out completely. Recently I’ve been taking some of the pictures that seem a little too “overpopulated” with info and taking them through what a two-step process I call a color compromise (patent not applied for).

First step involves desaturating the picture completely, while also turning the contrast way down, amping up the exposure and damn near banishing any shadows. This almost results in a bleached-out pencil drawing effect and emphasizes detail like crazy. Step two involves the slow re-introduction of color until only selected parts of the image render any hues at all, and making sure that the color that is visible barely, barely registers.

The final image can actually be a clearer “read” for your eyes than either the garish colored original or a complete b&w. Objects will stand out from each other a little more distinctly, and there will be an enhanced sensation of depth. It also suggests a time-travel feel, as if age has baked out the color. A little of this washed-out jeans look goes a long way, however, and this whole exercise is just to see if you can make the picture communicate a little better by allowing it to speak more quietly.

Compare the processed photo at the top, taken in the heart of the visually noisy Broadway district, with its fairly busy color original and see if any of this works for you. I completely stipulate that I may just be bending over backwards to try to salvage a negligible photo. But I do think that color should be a part of the discussion when we fault an image for being cluttered.

REDUCTION OF TERMS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

To me, photography is an art of observation. It’s about finding something interesting in an ordinary place. I’ve found it has little to do with the things you see, and everything to do with the way you see them. —Elliott Erwitt

ISOLATION IS A TRULY IRONIC CONDITION OF THE HUMAN ANIMAL. The strange thought that, for most of our lives, we are both awash in a sea of other people and totally alone is one of nature’s most profound paradoxes. Photography shows people in both of these conditions, and shooters must choose what illuminates a person’s story best—-his place among others or his seeming banishment from them. Sometimes both truths are in the same frame, and then you must, as Elliott Erwitt says, alter the way you see in favor of one or the other.

In the case of both of the images posted here, the person who “solely” occupies the frames was originally a stray element within a larger context, with the pictures framed, at first, to include nearby persons or crowds. On further examination, however, one or two compositional elements in each of the pictures convinced me, in both the case of the museum guard and the hurried gallery guest, that they could “hold” the pictures they were in without any other human presence in view, and so I created their isolation, something that was not their natural condition at the time.

I further “isolated” these two subjects by desaturating everything in the frame except their flesh tones. 1/10 sec., f/5.6, ISO 320, 35mm.

Part of this process is my ongoing curiosity in how far I can go in paring away extra visual information before the story impact of a photograph is amplified to its highest power. I’m sure you have all worked with many original images that are just too balky and talky, that are really “made” in the cropping process. To be sure, sometimes you’re just peeling away the rotten outer parts of an apple to reveal…..a rotten core! Other times, however, you are privileged to peel away just enough petals to render the rose at its best, and, with images of people, that can mean getting rid of almost all the people in the picture you began with.

In both these cases, I liked these people to be shown as if they were in command of small little universes of their own. Does that make the photographs sad? Lonely? Dignified? Tranquil? Yes to all these and anything else you can bring to it, because if cropping is the second part of the picture-making process, then seeing if your instinct “proofs out” with viewers is the final and most crucial part. I’m using every process I can to convey to you what I saw, or what I believe is worth seeing. It’s a collaborative process, and sometimes, I’m sure, I don’t hold up my part of the bargain. And still we press on.

Isolation is more than a human condition or a symptom of our times: it’s a compositional tool, a reduction of the equation of scene-making to its simplest, and hopefully truest, terms.

ANATOMY OF A BOTCH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE SHOULD BE A MIRROR-IMAGE, “NEGATIVE” COOKBOOK FOR EVERY REGULAR ONE PUBLISHED, since there are recipes for inedible failures, just as surely as there are ones for gustatory delights. It might be genuinely instructive to read an article called How To Turn A Would-Be Apple Pie Into A Shapeless Heap Of Glop or You, Too Can Make Barbecue Ribs Look Like The Aftermath Of A Cremation. So too, in photography, I believe I could easily pen an essay called How To Take Pictures That Make It Seem That You Never Touched A Camera Before.

In fact…..

In recent days, I’ve been giving myself an extra welt or two with the flagellation belt in horrified reaction to a shoot that I just flat-out blew.It was a walk through a classic hotel lobby, a real “someday” destination for myself that I finally got to visit and wanted eagerly to photograph. Thing is, none of that desire made it into the frames. Nor did any sense of drama, art, composition, or the basics of even seeing. It’s rare that you crank off as many shots as I did on a subject and wind up with a big steaming pile of nothing to show for it, but in this case, I seem to have been all thumbs, including ten extra ones where my toes should be.

So, if I were to write a negative recipe for a shoot, it would certainly contain a few vital tips:

First, make sure you know nothing about the subject you’re shooting. I mean, why would you waste your valuable time learning about the layout or history of a place when you can just aimlessly wander around and whale away? Maybe you’ll get lucky. Yeah, that’s what makes great photographs, luck.

Enjoy the delightful surprise of discovering that there is less light inside your location than inside the fourth basement of a coal mine. Feel free to lean upon your camera to supply what you don’t have, i.e., a tripod or a brain. Crank up the ISO and make sure that you get something on the sensor, even if it’s goo and grit. And shoot near any windows you have, since blowouts look so artsy contrasted with pitch blackness.

Resist the urge to have any plan or blueprint for your shooting. Hey, you’re an artist. The brilliance will just flow as you sweep your camera around. Be spontaneous. Or clueless. Or maybe you can’t tell the difference.

Stir vigorously and for an insane length of time with a photo processing program, trying to manipulate your way to a useful image. You won’t get there, but life is a journey, right? Even when you’re hopelessly lost in a deep dark forest.

************************

You could say that I’m being too Catholic about this, and I would counter that I’m not being Catholic enough.

Until I do penance.

Gotta go back someday and do it right.

And make something that really cooks.

WHAT IS HIP?

Shooting “from the hip” can be an urban photographer’s secret weapon. 1/40 sec., f/3.5, ISO 500, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN FACED WITH A COMPLETELY DIFFERENT APPROACH TO OUR PHOTOGRAPHY, the crabbier among us are liable to utter one of two responses. Both sound negative, but one could be positive:

Response #1: “I’d never do that!” (Emphatically negative. Discussion over. You will not persuade me.)

Response #2:”Why would I want to do that???” (Possibly as close-minded as response #1, but the person could be asking a legitimate question, as in, ‘show me the benefit in doing it your way, because I can’t imagine a single reason why I should change’.)

When first reading about the street photography technique of “shooting from the hip”, I was a definite response #2. Wasn’t going to slam the door on trying it, but failed to see what I would get out of it. The phrase means just what you’d think it does, referring to people with obvious cameras who do “street” work, shooting with the camera hanging at waist level, never bringing the viewfinder up to their eye. Subjects don’t cringe or lock up because you don’t “seem” to be taking a picture, and thus your images of them are far more unguarded and natural.

Now, suggesting this to a person who has never even owned a camera that didn’t have a viewfinder is a little like asking him to try to take pictures from the inside of a burlap sack. Kinda makes my inner control freak throw a bratrum (a brat tantrum). Think of it from my point of view. If I shoot manually all the time (I do) and if I need my viewfinder like Linus needs his blanket (cause, hey, I’m a tortured and insecure artist), then squeezing off a shot without even knowing if it’s in frame is, to say the least, counter-intuitive (French for “nuts”).

So there you have your honestly expressed Response #2.

Some things that finally made it worth at least trying:

It don’t cost nothin’.

I can practice taking pictures that I don’t care about. I wouldn’t be shooting these things or people even with total control, so what’s to lose?

Did I mention it don’t cost nothin’?

Shooters beware: clicking from the hip is far from easy to master. Get ready to take lots of photos that look like they came from your Urban Outfitter Soviet Union-era Plastic Toy Hipsta Camera. You want rakish tilt? You got it. You like edgy, iffy focus? It’s a given. In other words, you’ll spend a lotta time going through your day’s work like the Joker evaluating Vicki Vale’s portfolio (….”crap….crap….crap….” ). But you might eventually snag a jewel, and it feels so deliciously evil to procure truly candid shots that you may develop an addiction to the affliction. Observe a few basics: shoot as wide as you can, cause 35s, 50s and other primes won’t give you enough scope in composition at close range: go with as fast a shutter speed as the light will allow (in low light, compromise on the ISO): if possible, shoot f/5.6 or smaller: and, finally,learn how to pre-squeeze the autofocus and listen for its quiet little zzzz, then tilt the camera just far enough up to make sure everyone has a head, and go.

At worst, it forces you to re-evaluate the way you “see” a shot, since you have no choice but to accept what the camera could see. At best, you might see fewer bared fangs from people snarling, “hey is that a $&@*! camera?” inches from your nose. And that’s a good thing.

SET AND SHOOT

Shooting manually means learning to trust that you can capture what you see. 1/160 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AUTOMODES ON CAMERAS ARE SUPPOSED TO AFFORD THE PHOTOGRAPHER AN ENHANCED SENSE OF COMFORT AND SAFETY, since, you know, you’re protected from your very human errors by the camera’s loving, if soulless, oversight. Guess wrong on a shutter speed? The auto has your back. Blow the aperture? Auto is on the case. And you always get acceptable pictures.

That is, if you can put your brain on automode as well.

Okay, that statement makes the top ten list for most arrogant openings in all of Blogdom, 2014. But I stand by it. I don’t think you should get comfortable with your equipment calling the shots. However, getting comfortable with your equipment’s limits and strengths, and gradually relying on your own experience for consistent results through exploitation of that knowledge….now that’s another thing entirely. It’s the difference between driving cross-country on cruise control and knowing, from years of driving, where in the journey your car can shine, if you drive it intelligently.

Photographers call some hunks of glass their “go-to” lenses, since they know they can always get something solid from them in nearly any situation. And while we all tend to wander around aimlessly for years inside Camera Toyland, picking up this lens, that filter, those extenders, we all, if we shoot enough for a long time, settle back into a basic gear setup that is reliable in fair weather or foul.

This is better than using automodes, because we have chosen the setups and systems that most frequently give us good product, and we have picked up enough wisdom and speed from making thousands of pictures with our favorite gear that we can “set and shoot”, that is, calculate and decide just as quickly as most people do with automodes…..and yet we keep the vital link of human input in the creative chain.

Like most, I have my own “go-to” lens and my own “safe bet” settings. But, just as you save time by not trying to invent the wheel every time you step up, you likewise shouldn’t be averse to greasing an old wheel to make it spin more smoothly.

How about that, I also made the top ten list for unwieldy metaphors.

A good day.

ON THE STRAIGHT AND NARROW

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE NARROW STREETS OF LOWER MANHATTAN WERE NEVER DESIGNED TO ACCOMMODATE the claustrophobic jam of commerce, foot traffic and skyscrapers that have characterized the neighborhood since the early 20th century. I should back that up and acknowledge that, for some locals, the streets of lower Manhattan were never designed,period. New York’s growth has always come in rangy spurts and jolts, much like a gangly adolescent that shoots upward and outward overnight without any apparent plan, and yet, those unruly explosions are also what delight the photographer’s eye and make the city an inexhaustible laboratory for technique.

Shooting down the slits that pass for side streets and alleys in lower Manhattan is enough to make even the most seasoned native feel like he or she is being shut up in a tomb, but I am drawn to going even further, and over-emphasizing the extreme dimensions peculiar to the area. That, for me, means shooting with as wide a lens as I have handy, distortion be damned. Actually, it’s distortion be welcomed, since I think that the horizontal lines of the buildings create a much more dramatic lead-in for the eye as they race far away from the foreground. And since ultra-wide magnify front-to-back distances, the bigness and closeness of the city is jacked into a real exaggeration, but one that serves my purpose.

It helps to crouch down and tilt up when composing the shot, and to make sure that you don’t crop passersby out of the shot, since they will add to the drama even more as indications of scale. I have certainly gone too far more than once and rendered rectangular buildings into futuristic trapezoids, but the aim of each image will dictate what you’re going for. Also, in many of these shots, I decide, after much dithering, to choose monochrome over color, but I always shoot the originals in color, since they respond better to re-contrasting once they’re desaturated.

The magic about Manhattan is that no camera can ever tame her or show all her beauty and/or ugliness. It’s somthing of a fool’s errand to try to take the picture of NYC. Better to take a picture you like and add it to the ongoing story.

TAKING FLIGHT ONCE MORE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE CHARGES GIVEN TO ALL PHOTOGRAPHERS IS TO MARK THE PASSAGE OF TIME, to chronicle and record, to give testimony to a rapidly vanishing world. Certainly interpretation, fantasy, and other original conceptions are equally important for shooters, but there has been a kind of unspoken responsibility to use the camera to bear witness. This is especially difficult in a world bent on obliterating memory, of dismantling the very sites of history.

Humorist and historian Bill Bryson’s wonderful book, One Summer: America 1927 frames the amazing news stories of its title year around its most singular event, the solo transatlantic flight of Charles A. Lindbergh. A sad coda to the story reveals that nothing whatever remains of Roosevelt Field, the grassy stretch on Long Island from which the Lone Eagle launched himself into immortality, with the exception of a small plaque mounted on the back of an escalator in the mall that bears the field’s name. Last week, hauled along on a shopping trip to the mall with relatives, I made my sad pilgrimage to said plaque, lamenting, as Bryson did, that there is nothing more to photograph of the place where the world changed forever.

Then I got a little gift.

The mall is under extensive renovation as I write this, and much of the first floor ceiling has been stripped back to support beams, electrical systems and structural gridwork. Framed against the bright bargains in the mall shops below, it’s rather ugly, but, seen as a whimsical link to the Air Age, it gave me an idea. All wings of the Roosevelt Field mall feature enormous skylights, and several of them occur smack in the middle of some of the construction areas. Composing a frame with just these two elements, a dark, industrial space and a light, airy radiance, I could almost suggest the inside of a futuristic aerodrome or hangar, a place of bustling energy sweeping up to an exhilarating launch hatch. To get enough detail in this extremely contrasty pairing, and yet not add noise to the darker passages, I stayed at ISO 100, but slowed to 1/30 sec. and a shutter setting of f/3.5. I still had a near-blowout of the skylight, saving just the grid structure, but I was really losing no useful detail I needed beyond blue sky. Easy choice.

Thus, Roosevelt Field, for me, had taken wing again, if only for a moment, in a visual mash-up of Lindbergh, Flash Gordon, Han Solo, and maybe even The Rocketeer. In aviation, the dream’s always been the thing anyway.

And maybe that’s what photography is really for…trapping dreams in a box.

A BIG BOX OF LONELY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY CAN GO TWO WAYS ON CONTEXT. It can either seek out surroundings which comment organically on subjects (a lone customer at a largely empty bar, for example) or it can, through composition or editing, artificially create that context (five people in an elevator becomes just two of those people, their locked hands taking up the entire frame). Sometimes, images aren’t about what we see but what we can make someone else seem to see.

Creating your own context isn’t really “cheating” (are we really still using that word?), because you’re not creating a new fact in the photograph, so much as you are slapping a big neon arrow onto said fact and saying, “hey look over here.” Of course, re-contextualizing a shot can lead to deliberate mis-representation of reality in the wrong hands (see propaganda, use of), but, assuming we’re re-directing a viewer’s attention for purely aesthetic reasons (using our powers for good), it can make a single photo speak in vastly different ways depending on where you snip or pare.

In the above situation, I was shooting through the storefront window of a combined art studio and wine bar (yes, I hang with those kind of people), and, given that the neighborhood I was in regularly packed folks in on “gallery hop” nights, the place was pretty jammed. The original full frame showed everything you see here, but also the connecting corridor between the studio and the wine bar which was, although still crowded, a lot less claustrophobic than this edited frame suggests.

And that’s really the point. Urban “hangs” that are so over-attended can give me the feeling of being jammed into a phone booth, like I’m part of some kind of desperately lonely lemming family reunion, so I decided to make that crushed sensation the context of the picture. Cropping down to a square frame improved the balance of the photograph but it also made these people look a little trapped, although oddly indifferent to their condition. The street reflections from the front plane of glass also add to the “boxed in” sensation. It’s a quick way to transform a snap into some kind of commentary, and you can either accept my choice or pass it by. That’s why doing this is fun.

Urban life presents a challenging series of social arrangements, and context in photographs can force a conversation on how that affects us.

ELEMENTARY, MY DEAR NIKON

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY IS OFTEN DEFINED CLASSICALLY AS “WRITING WITH LIGHT“, but I often wonder if a better definition might be “capitalizing on light opportunities”, since it’s not really what subject matter we shoot but light’s role in shaping it that makes for strong images. We have all seen humble objects transformed, even rendered iconic, based on how a shooter perceives the value of light, then shapes it to his ends. That’s why even simple patterns that consist of little more than light itself can sometimes be enough for a solid photograph.

If you track the history of our art from, say, from the American Civil War through today’s digital domain, you really see a progression from recording to interpreting. If the first generally distributed photographs seen by a mass audience involve, say, the aftermath of Antietam or Gettysburg, and recent images are often composed of simple shapes, then the progression is very easy to track. The essence is this: we began with photography as technology, the answer to a scientific conundrum. How do we stop and fix time in a physical storage device? Once that very basic aim was achieved, photographers went from trying to just get some image (hey, it worked!) to having a greater say in what kind of image they wanted. It was at this point that photography took on the same creative freedom as painting. Brushes, cameras, it doesn’t matter. They are just mediums through which the imagination is channeled.

In interpreting patterns of elementary shapes which appeal on their own merit, photographers are released from the stricture of having to endlessly search for “something to shoot”. Some days there is no magnificent sunrise or eloquent tree readily at hand, but there is always light and its power to refract, scatter, and recombine for effect. It’s often said that photography forced painting into abstraction because it didn’t want to compete with the technically perfect way that the camera could record the world. However, photography also evolved beyond the point where just rendering reality was enough. We moved from being reporters to commentators, if you like. Making that journey in your own work (and at your own pace) is one of the most important step an art, or an artist, can take.

MINIMUM SHOW, MAXIMUM SEE

There are only two design elements in this image. Does it really need any more? 1/160 sec., f/4, ISO 100, 24mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LOOK AT THE EARLIEST PHOTOGRAPHIC WORK OF NEARLY ANYONE and you will see a general attempt to frame up a scene and attempt to show, well, everything within range of the camera. It’s a time when we produce our most inclusive panoramas, our most crowded city scenes, our most enormous circus midways. Our pictures may be stories, but, at first, our stories have a bit of a problem getting to the point. We are so inclusive of raw data that every snap of life at the beach becomes a page out of Where’s Waldo? Thus, the very first real talent young photographers show is the ability to trim all that visual fat and get the maximum see for the minimum show.

Of course, when we are mere puppies, it seems counter-intuitive to say that showing less will actually make us see more. Minimalism doesn’t come easily to us, since we are afraid, at first, that we’re leaving something “important” out. Everyone comes to terms with this eventually if they shoot long enough, but we all arrive at the wisdom of it via various journeys. For me, it was my first attempts at still life compositions, which really are the most edited exercises we do. For these kinds of photos, it’s really about knowing what to leave out, or at least when to stop adding. And when a picture works, there is the nagging curiosity as to why….an inquiry which often leads to the conclusion that we used just what we needed, and then stopped.

Sometimes I get a sense of how little I need in a picture while I’m shooting. Many times, though, it comes to me in the editing or cropping process. If I snip something off of a picture and it doesn’t fall apart, I start wondering how much more I can pare away and still say what I’m trying to say. Learning, in recent years, how to compose again for a square frame has really been helpful, too, since it forces you into a pre-determined space limit. You can’t paint any wider than the canvas, if you will. You yourself might find other ways to get to the core balance your story needs. There is no true or single path.

I started the above image in a wide graveyard, then several graves and a tree, then one grave marker and a tree, then just the marker, and finally a portion of the marker. But in what I wound up with, aren’t all the elements I cut away really present for the viewer mentally anyway?

It’s often said, as a generalization, that painters start with nothing and add until they get the picture, while photographers start with everything and strip information away until they see just what they need. I really see a lot of photography that way. Tell the story with as few elements as you can and walk away. Minimum show for maximum see.

Not nearly so counter-intuitive, after all.